What is Meckel’s diverticulum

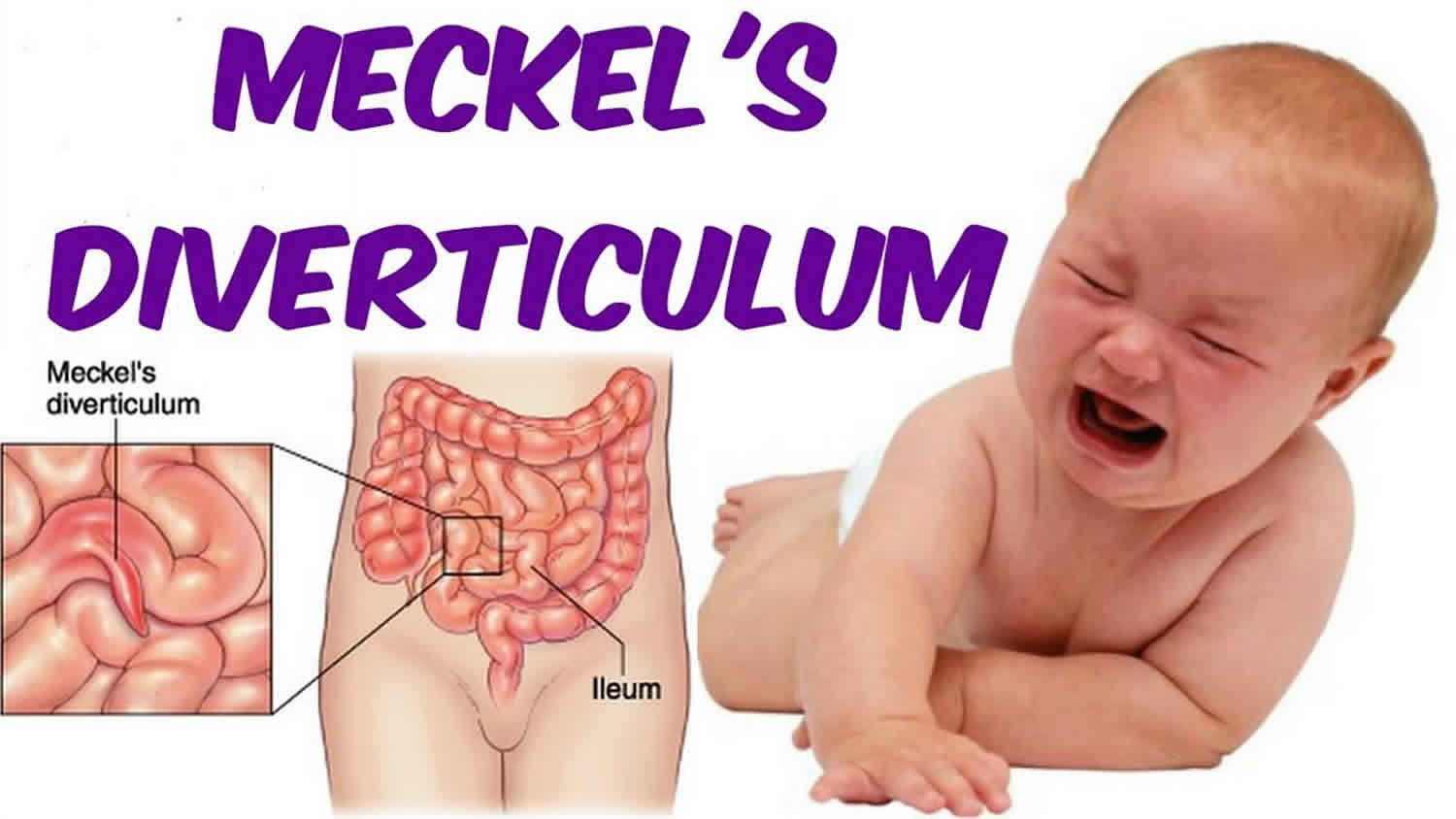

Meckel’s diverticulum is a small pouch on the wall of the lower part of the small intestine, near the junction of the small and large intestines. A normal intestine does not have a pouch. Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common congenital (present at birth) gastrointestinal anomaly which occurs in about 2% of infants 1. Autopsy records show that Meckel diverticulum occurs in about 2% of the general population 2. The male-to-female ratio is 3:1 for patients with symptomatic diverticula, but it is 1:1 for patients with asymptomatic Meckel’s diverticulum. A Meckel’s diverticulum is formed when the fetus is in the womb. The pouch is made up of leftover tissue from the baby’s digestive tract. Meckel’s diverticulum is not made of the same type of tissue as the small intestine, but instead, is made of the type of tissue found in the stomach or the pancreas.

The “rule of 2s” has been used to describe a Meckel’s diverticulum conveniently. Meckel’s diverticulum usually measures 2 inches long and is located in the ileum approximately 2 feet from the ileocecal valve. Meckel’s diverticulum is twice as common in females. It can contain 2 types of tissue (gastric or pancreatic). It is a true diverticulum because it contains all the layers of the small bowel wall. The diverticulum can sometimes have ectopic tissue within the walls. The embryonic origin of the ectopic tissue is unknown. It is estimated approximately 15% of patients will have ectopic tissue within the diverticulum 1.

The tissue in Meckel’s diverticulum can produce acid, just as the tissue of the stomach does. The intestinal lining is sensitive to being in contact with acid, and eventually an ulcer can form. The ulcer can rupture, causing waste products from the intestine to leak into the abdomen. A serious abdominal infection called peritonitis can result. The intestine can also become blocked by Meckel’s diverticulum.

Most people who have a Meckel’s diverticulum have no symptoms. Only about 1 in 25 people who are born with it have problems. The patient often becomes symptomatic in the first decade of life with an average age of 2.5. Risk factors for increased risk of developing symptoms include age younger than 50, male gender, diverticulum greater than 2 cm in length, the presence of ectopic tissue, broad-based diverticulum, and fibrous bands attached to the Meckel’s diverticulum.

Symptoms vary by age. Infants and children may have bleeding from the rectum. Sometimes blood can be seen in the stool. In adults, the intestine may become blocked. Symptoms of this are stomach pain and vomiting. Other symptoms include fever, constipation, and swelling of the stomach. Symptoms of Meckel’s diverticulum may look like other conditions or medical problems. Please consult your child’s doctor for a diagnosis.

The most common complication of Meckel’s diverticulum in children is rectal bleeding resulting in anemia. The most common complication in adults is a small bowel obstruction. The etiology of the obstruction may be secondary to the omphalomesenteric band, internal hernia, volvulus around the vitelline duct remnants, and intussusception in which the diverticulum acts as the lead point. The diverticulum can become inflamed resulting in Meckel’s diverticulitis with perforation and peritonitis.

People who don’t have symptoms can be monitored by their doctor.

Treatment for a Meckel’s diverticulum is needed for people who have symptoms. This may include surgery to remove the pouch and repair the intestine. Risks of surgery include bleeding, swelling, tearing, and folding of the intestines. People who have surgery to remove the Meckel’s diverticulum often recover to live a full life. The Meckel’s diverticulum pouch does not grow back.

Meckel’s diverticulum causes

Meckel’s diverticulum is caused by the incomplete obliteration of the omphalomesenteric (vitellointestinal) duct which connects the yolk sac to the gut in the developing embryo 1. The omphalomesenteric (vitellointestinal) duct provides nutrition until the placenta forms. At about 7 weeks of gestation, the omphalomesenteric (vitellointestinal) duct separates from the intestine. If the duct fails to partially or entirely separate and involute, it can result in an omphalomesenteric cyst, omphalomesenteric fistula that drains through the umbilicus, or a fibrous band from the diverticulum to the umbilicus which can cause an obstruction. If there is no additional attachment, it forms into a Meckel’s diverticulum.

In a Meckel’s diverticulum, the ectopic gastric mucosa secretes an acid that is not neutralized and resulting in ulceration of the adjacent mucosa leading to painless rectal bleeding. The ectopic mucosa can also originate from the pancreas, jejunum, or a combination of mucosa. The site of the bleeding is usually distal to the diverticulum and not within the diverticulum. The presence of a fibrous band attached to the diverticulum can result in small bowel obstruction. The diverticulum can also act as a lead point for an intussusception leading to small bowel obstruction. The incarceration of the Meckel’s diverticulum can also result in a small bowel obstruction. Inflammation in the diverticulum can result in Meckel’s diverticulitis with perforation.

Meckel’s diverticulum symptoms

When the intestine develops an ulcer, significant bleeding can result, causing anemia (low numbers of red blood cells in the bloodstream). The symptom seen most often with Meckel’s diverticulum is the passage of a large amount of dark red blood from the rectum. There may also be brick-colored, jelly-like stool present. Passing the blood is usually painless, although some children may have abdominal pain.

If your child passes blood or a bloody stool from the rectum, you should contact your child’s doctor as soon as possible.

If enough blood is lost, a child may go into shock, which is a life-threatening situation. A serious infection may also occur if the intestine ruptures and leaks waste products into the abdomen.

Symptoms of Meckel’s diverticulum may look like other conditions or medical problems. Please consult your child’s doctor for a diagnosis.

Meckel’s diverticulum complications

Meckel’s diverticulum most commonly discovered as an incidental finding on laparotomy or laparoscopy, Meckel diverticulum can be associated with life-threatening disease states 3. Retrospective studies suggest that the onset and frequency of complications decrease during life. The risk of complications ranges from 4% to 25% in various studies. Complications manifest as the following:

- Ulceration

- Hemorrhage

- Small-bowel obstruction

- Diverticulitis

- Perforation

In an excellent population-based study by Cullen et al. 4 that covered patient data over a period of 42 years, the lifetime risk of developing a complication that requires surgery was estimated to be 6.4%.

Hemorrhage

Hemorrhage is the most common complication of Meckel diverticulum, accounting for about 20-30% of all complications. It is more common in children younger than 2 years and in males. The patient complains of passing bright red blood in the stools. Bleeding may range from minimal, recurrent episodes of hematochezia to massive, shock-producing hemorrhage.

The rate of bleeding can be assessed on the basis of the following:

- Quantity of blood lost in the stools

- Appearance of the material passed through the rectum

- Hemodynamic state

Hemorrhage from a Meckel diverticulum may or may not be associated with abdominal pain or tenderness. Patients may also present with weakness and anemia and may have a history of self-limiting episodes of intestinal bleeding.

Characteristics of hemorrhage based on the appearance of stools include the following:

- Bright red blood in the stools – Brisk hemorrhage

- Tarry stools – The bleeding is probably minor and associated with slow intestinal transit; tarry stools are commonly observed in patients with upper gastrointestinal (gastrointestinal) bleeding, because transit through the bowel produces alteration of blood

- Currant jelly stools – Associated with copious mucus owing to ischemia of the bowel; commonly observed in intussusception

- Blood-streaked stools – A sign of fissure-in-ano

The gastric mucosa found in the diverticulum (see the image below) may form a chronic ulcer and may also damage the adjacent ileal mucosa because of acid production. Ectopic gastric mucosa is found in about 50% of all Meckel diverticula; in bleeding Meckel diverticula, the incidence increases to 75%. Perforation may occur, and the patient then presents with an acute abdomen, often associated with air under the diaphragm, best visualized on an erect chest radiograph.

When a patient presents with painless lower gastrointestinal bleeding, Meckel diverticulum should always be suspected. Panendoscopy helps exclude disease in the upper gastrointestinal and colorectal regions, the two most common sites of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Intestinal obstruction

This is another frequent complication; it is observed in 20-25% of patients with symptomatic Meckel diverticulum. The diagnosis of bowel obstruction due to Meckel diverticulum may not be established preoperatively. At exploration, Meckel diverticulum may be identified as the cause of obstruction.

Various mechanisms of intestinal obstruction occur with Meckel diverticulum as a causative factor. Because the omphalomesenteric duct may be attached to the abdominal wall by a fibrotic band, a volvulus of the small bowel around the band may occur. The diverticulum may also form the lead point of an intussusception and cause obstruction. Infrequently, a tumor arising in the wall of the diverticulum may form the lead point for intussusception. When incarcerated in an inguinal hernia, a Meckel diverticulum is called a Littré hernia.

Patients with intestinal obstruction due to Meckel diverticulum present with abdominal pain, vomiting, and obstipation. Radiography of the abdomen may indicate an ileus or frank stepladder air-fluid levels, as observed in dynamic intestinal obstruction.

In cases of intussusception, patients may also present with a palpable lump in the lower abdomen and currant jelly stools.

Diverticulitis

This condition develops in approximately 10-20% of patients with symptomatic Meckel diverticulum, occurring more often in the elderly population. Patients may present with symptoms of intermittent, crampy abdominal pain and tenderness in the periumbilical area. Perforation of the inflamed diverticulum leads to peritonitis.

Stasis in the diverticulum, especially in one with a narrow neck, causes inflammation and secondary infection leading to diverticulitis. Diverticular inflammation can lead to adhesions, which cause intestinal obstruction.

Umbilical anomalies

These occur in up to 10% of patients and consist of fistulas, sinuses, cysts, and fibrous bands between the diverticulum and the umbilicus. A patient may present with a chronic discharging umbilical sinus superimposed by infection or excoriation of periumbilical skin. There may be a history of recurrent infection, sinus healing, or abdominal-wall abscess formation. When a fistula is present, intestinal mucosa may be identified on the skin.

Cannulation and injection with radiographic contrast help to delineate the entire tract and aid in planning a surgical approach for cure. A discharging sinus should be approached surgically with a view toward correction. Exploratory laparotomy may be required.

When found at laparotomy, a fibrous band should be excised because of the risk of internal herniation and volvulus.

Tumor

This is the pathology least commonly associated with Meckel diverticulum and is reported in approximately 4-5% of complicated Meckel diverticulum cases. Of the various types of tumors reported, leiomyoma is the one that is most frequently found, followed by leiomyosarcoma, carcinoid tumor, and fibroma. One case of ectopic gastric adenocarcinoma has been reported. Lipoma and angioma have also been found 5.

Other complications

Other reported complications in Meckel diverticulum are vesicodiverticular fistulas, “daughter” diverticula (formation of a diverticulum within a Meckel diverticulum), and formation of stones and phytobezoar in the Meckel diverticulum.

Meckel’s diverticulum diagnosis

Although a Meckel’s diverticulum exists at birth, doctors do not test for it. Contact your doctor if you or your child develops symptoms.

In addition to a complete medical history and physical exam, imaging tests may be done to evaluate the intestinal tract. Other tests may include:

- Your doctor can do a test called a Meckel’s scan (Technetium-99m pertechnate radioisotope scanning). For Meckel’s scan, a substance called technetium is injected into your child’s bloodstream though an intravenous (IV) line. The technetium can be seen on an X-ray in areas of the body where stomach tissue exists, such as the Meckel’s diverticulum. If you have a diverticulum, the fluid will gather around the pouch. This allows the doctor to confirm a diagnosis.

- Blood test. This test checks for anemia or infection. A stool sample may be checked for blood.

- Barium enema and small bowel series. This procedure is done to examine the large intestine for abnormalities. A fluid called barium is given into the rectum as an enema. Barium is a metallic, chemical, chalky, liquid used to coat the inside of organs so that they will show up on an X-ray.). An X-ray of the abdomen shows narrowed areas, blockages, and other problems.

- Rectosigmoidoscopy. A small, flexible tube with a camera on the end is inserted into your child’s rectum and sigmoid colon (last part of the large intestine). The inside of the rectum and large intestine are evaluated for bleeding, blockage, and other problems.

Meckel’s diverticulum treatment

Specific treatment for Meckel’s diverticulum will be determined by your child’s doctor based on the following:

- The extent of the problem

- Your child’s age, overall health, and medical history

- Your child’s tolerance for specific medications, procedures, or therapies

- Expectations for the course of the problem

- The opinion of the health care providers involved in the child’s care

- Your opinion and preference

Doctors will usually recommend that a Meckel’s diverticulum that is causing symptoms (such as bleeding) be surgically removed. Under general anesthesia, an incision will be made in the abdomen and the abnormal tissue will be removed. Stitches and/or a special tape called steri strips will be used to close the incision when the operation is completed.

Your child’s doctor or nurse will give you instructions to follow regarding your child’s diet, pain medications, bathing, and activity at home.

There are usually no long-term problems after Meckel’s diverticulum is repaired.

Meckel’s diverticulum surgery

Absolute indications for resection in Meckel diverticulum are hemorrhage, intestinal obstruction, diverticulitis, and umbilicoileal fistulas 6. In asymptomatic Meckel diverticulum, excision is generally performed if the neck of the diverticulum is narrow or if stasis is present. Tangential excision with suture closure of the base is performed. In complicated cases, the diverticulum must be resected.

Resection is recommended in the following cases:

- Patients younger than 40 years

- Diverticula longer than 2 cm

- Diverticula with narrow necks

- Diverticula with fibrous bands

- Suspected ectopic gastric tissue

- Inflamed, thickened diverticula

Removal of a healthy diverticulum in the presence of peritonitis, Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, or any other complication that would militate against resection is not advised.

Four possible surgical procedures may be considered, as follows:

- Diverticulectomy with suture closure of the base

- Wedge resection of the intestinal wall containing the diverticulum with suture closure

- Segmental resection of the intestine, including the diverticulum, and end-to-end anastomosis

- Division of the fibrous band, with or without diverticulectomy

Preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative management of Meckel diverticulum follows the general principles of abdominal surgery and includes the use of perioperative antibiotics. Additional surgical considerations include the following:

- Hemorrhage – In cases of hemorrhage, wedge or segmental resection ensures adequate excision of the part containing gastric and ulcerated ileal mucosa

- Intestinal obstruction – In cases of intestinal obstruction, the viability of the bowel wall delineates the extent of excision

- Segmental resection – This is advised in children with broad-based diverticula in whom the risk of ileal stenosis is greater if diverticulectomy or wedge resection is performed

- Umbilical sinus and fistula – These may necessitate excision of the umbilicus

- Meckel diverticulitis – Because Meckel diverticulitis often mimics appendicitis, examine the distal ileum for diverticulitis when the appendix is discovered to be normal during exploration for suspected appendicitis

Principles of surgical treatment include the following:

- Ensuring adequate blood supply to the resectional margins

- Recognition of bowel viability

- Awareness of suture-line tension

- Alertness to the potential for intestinal stenosis due to narrowing

Handsewn technique versus stapling

All procedures may be carried out either by handsewn technique or by stapling, depending on the preference of the surgeon. Stapling enables faster resection of a Meckel diverticulum without the need to open the bowel’s lumen, thus avoiding potential septic and postoperative complications. Meckel diverticulum, which fits well into the stapling device, is easy to remove, and removal has a low complication rate, especially when the diverticulum was found incidentally.

Laparoscopic management

Laparoscopic techniques are increasingly being used for Meckel diverticulectomy and intestinal resection 7. With advancements in technology, minimally invasive therapeutic interventions, such as intracorporeal resection or laparoscopic-assisted extracorporeal resection, can easily be performed. At present, laparoscopic management of Meckel diverticulum is largely limited to symptoms of abdominal pain and GI bleeding. For symptoms of obstruction, diagnostic laparoscopy is not recommended, because of difficulties in establishing pneumoperitoneum 8.

References- An J, Zabbo CP. Meckel Diverticulum. [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499960

- Meckel diverticulum. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/194776-overview

- Dumper J, Mackenzie S, Mitchell P, Sutherland F, Quan ML, Mew D. Complications of Meckel’s diverticula in adults. Can J Surg. 2006 Oct. 49(5):353-7.

- Cullen JJ, Kelly KA, Moir CR, Hodge DO, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Surgical management of Meckel’s diverticulum. An epidemiologic, population-based study. Ann Surg. 1994 Oct. 220(4):564-8; discussion 568-9

- Thirunavukarasu P, Sathaiah M, Sukumar S, Bartels CJ, Zeh H 3rd, Lee KK, et al. Meckel’s diverticulum–a high-risk region for malignancy in the ileum. Insights from a population-based epidemiological study and implications in surgical management. Ann Surg. 2011 Feb. 253(2):223-30

- McKay R. High incidence of symptomatic Meckel’s diverticulum in patients less than fifty years of age: an indication for resection. Am Surg. 2007 Mar. 73 (3):271-5.

- Hosn MA, Lakis M, Faraj W, Khoury G, Diba S. Laparoscopic approach to symptomatic meckel diverticulum in adults. JSLS. 2014 Oct-Dec. 18, 4

- Ruscher KA, Fisher JN, Hughes CD, Neff S, Lerer TJ, Hight DW, et al. National trends in the surgical management of Meckel’s diverticulum. J Pediatr Surg. 2011 May. 46 (5):893-6.