Morganella Morganii infection

Morganella morganii is a gram-negative rod commonly found in the environment and in the intestinal tracts of humans, mammals, and reptiles as normal flora. Despite its wide distribution, it is an uncommon cause of community-acquired infection and is most often encountered in postoperative and other hospital acquired (nosocomial) settings. Morganella morganii infections respond well to appropriate antibiotic therapy; however, its natural resistance to many beta-lactam antibiotics may lead to delays in proper treatment.

The genus Morganella belongs to the tribe Proteeae of the family Enterobacteriaceae 1. The Proteeae, which also include the genera Proteus and Providencia, are important opportunistic pathogens capable of causing a wide variety of nosocomial infections. According to the modern classification, Morganella is a type genus of a novel Morganellaceae family. This family consists of the following 8 genera: Arsenophonus, Cosenzaea, Moellerella, Morganella, Photorhabdus, Proteus, Providencia, and Xenorhabdus 2.

In the late 1930s, Morganella morganii was identified as a cause of urinary tract infections. Anecdotal reports of nosocomial infections began to appear in the literature in the 1950s and 1960s. Tucci and Isenberg 3 reported a cluster epidemic of Morganella morganii infections occurring over a 3-month period at a general hospital in 1977. Of these infections, 61% were wound infections and 39% were urinary tract infections.

In 1984, McDermott 4 reported 19 episodes of Morganella morganii bacteremia in 18 patients during a 5.5-year period at a Veterans Administration hospital. Eleven of the episodes occurred in surgical patients. The most common source of bacteremia was postoperative wound infection, and most infections occurred in patients who had received recent therapy with a beta-lactam antibiotic. Other important epidemiological risk factors in these studies included the presence of diabetes mellitus or other serious underlying diseases and advanced age.

In 2011, Kwon et al 5 reported a case of a 65-year-old man with an infected aortic aneurysm in which the pathogen was Morganella morganii. Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion and imaging tests.

Morganella morganii is a rare cause of severe invasive disease. It accounts for less than 1% of nosocomial infections. Morganella morganii is usually opportunistic pathogen in hospitalized patients, particularly those on antibiotic therapy.

Morganella morganii causes

Morganella morganii is an opportunistic bacterial pathogen shown to cause a wide range of clinical and community-acquired infections. Morganella morganii is a frequent cause of urinary tract infections (UTIs), septicemia, and wound infections 6. Morganella morganii has occasionally been associated with pathologies of diverse localizations such as a brain abscess 7, liver abscess 8, chorioamnionitis 9, peritonitis 10, pericarditis 11, septic arthritis 12, rhabdomyolysis 13, necrotizing fasciitis following snakebites 14, bilateral keratitis 15, neonatal sulfhemoglobinemia 16, and even non-clostridial gas gangrene 17. Erlanger et al. 18 reported that Morganella morganii bacteremia cases are more commonly accompanied by complications or by fatal consequences in comparison to Escherichia coli.

Morganella morganii urinary tract infections

Morganella morganii is commonly recovered from urine cultures in patients with long-term indwelling urinary catheters 19.

In a study of 135 consecutive patients with symptomatic, complicated, multidrug-resistant urinary tract infections, nearly 10% were infected with Morganella morganii.

Like Proteus species, Morganella morganii has properties that enhance its ability to infect the urinary tract; these include motility and the ability to produce urease.

Urolithiasis is associated with both genera. Members of the tribe Proteeae account for approximately 50% of cases of urolithiasis associated with urinary tract infections in children.

Morganella morganii perinatal infections

Morganella morganii has been associated with perinatal infection. Four cases of chorioamnionitis and one case of postpartum endometritis have been reported, and each case involved immunocompetent women 20.

Three of the women had received parenteral treatment with ampicillin prior to delivery.

In 2 of the pregnancies, the neonates were not infected.

A third neonate developed early-onset sepsis and Morganella morganii bacteremia. He was treated successfully with 10 days of cefotaxime and gentamicin. A fourth neonate, born at 24 weeks’ gestation, died within the first 38 hours of life. Morganella morganii was recovered from this neonate’s blood, pleural fluid, and peritoneal fluid cultures.

The fifth case occurred in a mother who had repeated exposures to beta-lactam antibiotics in the months prior to delivery for rheumatic fever prophylaxis and pharyngitis and then had intrapartum ampicillin for chorioamnionitis. Her neonate, born at 35 weeks’ gestation, was treated empirically with intravenous ampicillin and gentamicin immediately after delivery, but he developed respiratory distress and petechial and purpuric skin lesions on the second day of life. A chest radiograph revealed a lobar infiltrate. Blood culture findings were positive for Morganella morganii that was resistant to ampicillin and susceptible to cefotaxime and gentamicin. He recovered following a 14-day course of cefotaxime and gentamicin. His mother remained febrile after delivery, with evidence of endometritis and subsequent Morganella morganii urinary tract infection. Her isolate was resistant to ampicillin and gentamicin and was treated successfully with imipenem-cilastatin.

Two cases of early-onset neonatal sepsis in the absence of maternal infection have been reported. Both involved 32-week–premature neonates born to mothers who had received dexamethasone and ampicillin prior to delivery. Both neonates were treated with cefotaxime and amikacin. One neonate’s sepsis responded to treatment; the other neonate died from Morganella morganii infection.

Morganella morganii late-onset neonatal infection

Late-onset neonatal infection has been reported in 2 neonates: (1) a neonate born at term who presented on the 11th day of life with fever, irritability, and Morganella morganii bacteremia and (2) a 15-day-old neonate with Morganella morganii meningitis and brain abscess 21.

Morganella morganii necrotizing fasciitis

Fatal necrotizing fasciitis caused by Morganella morganii and Escherichia coli was reported in a 1-day-old neonate who had been inadvertently dropped into a toilet bowl during a home delivery 22.

Morganella morganii skeletal infections

Four cases of Morganella morganii septic arthritis have been reported in adults. All presented as chronic indolent infections. In contrast to the aggressive and destructive joint disease associated with Proteus mirabilis septic arthritis, the cases of Morganella morganii arthritis were remarkable for their benign clinical presentations and lack of joint damage despite a prolonged course 23.

Morganella morganii snakebites

Morganella morganii is commonly found in the mouths of snakes. As a result, it is one of the organisms recovered most often from snakebite infections. Jorge (1994) recovered Morganella morganii from 57% of abscesses occurring at the site of Bothrops (ie, the American Lanceheads) bites 24.

Morganella morganii scombroid poisoning

Morganella morganii produces the enzyme histidine decarboxylase, which reacts with histidine, a free amino acid present in the muscle of some species of fin fish, including tunas, mahimahi, sardines, and mackerel. When these fish are improperly stored, spoilage from Morganella morganii may cause the decarboxylation of histidine into histamine. Scombroid poisoning, an anaphylacticlike clinical syndrome, is caused by ingestion of the histamine-containing fish 25.

Morganella morganii infections in people with AIDS

Two case reports of Morganella morganii infection in patients with AIDS exist: a 45-year-old man with meningitis 26 and a 31-year-old man with pyomyositis 27.

Morganella morganii bacteremia

In a retrospective review of 73 patients with Morganella morganii bacteremia in Taiwan, 70% cases were community acquired and 45% were associated with polymicrobial bacteremia. The most common portals of entry were the urinary tract and hepatobiliary tract. Polymicrobial infection was most commonly associated with hepatobiliary disease. The overall mortality rate was 38%. The most important risk factor for mortality was inappropriate antibiotic therapy 28.

Morganella morganii CNS infections

CNS infections are rare. Six adult cases have been reported, including 3 cases of meningitis and 3 cases of brain abscess. The most common presentation was fever and altered mental status. Two of the patients with meningitis died. Two patients with brain abscess survived, one with long-term neurological complications 29.

Risk factors for Morganella morganii infection

Risk factors for Morganella morganii infection include the following:

- Prior exposure to ampicillin and other beta-lactam antibiotics

- Diabetes mellitus

- Advanced age

- Surgical procedures

- Perinatal exposure

- Abscesses or soft tissue infections following snakebite

Morganella morganii prevention

Prevent Morganella morganii infection by observing appropriate infection control practices and judiciously using beta-lactam antibiotics.

Morganella morganii symptoms

Physical findings are similar to those of other gram-negative infections.

Ecthyma gangrenosum–like eruptions and hemorrhagic bullae have been associated with Morganella morganii sepsis.

One 15-year-old girl with recurrent episodes of Henoch-Schönlein purpura was found to have a tuboovarian abscess caused by Morganella morganii. Treatment of the infection resulted in complete remission of the vasculitis 30.

Morganella morganii diagnosis

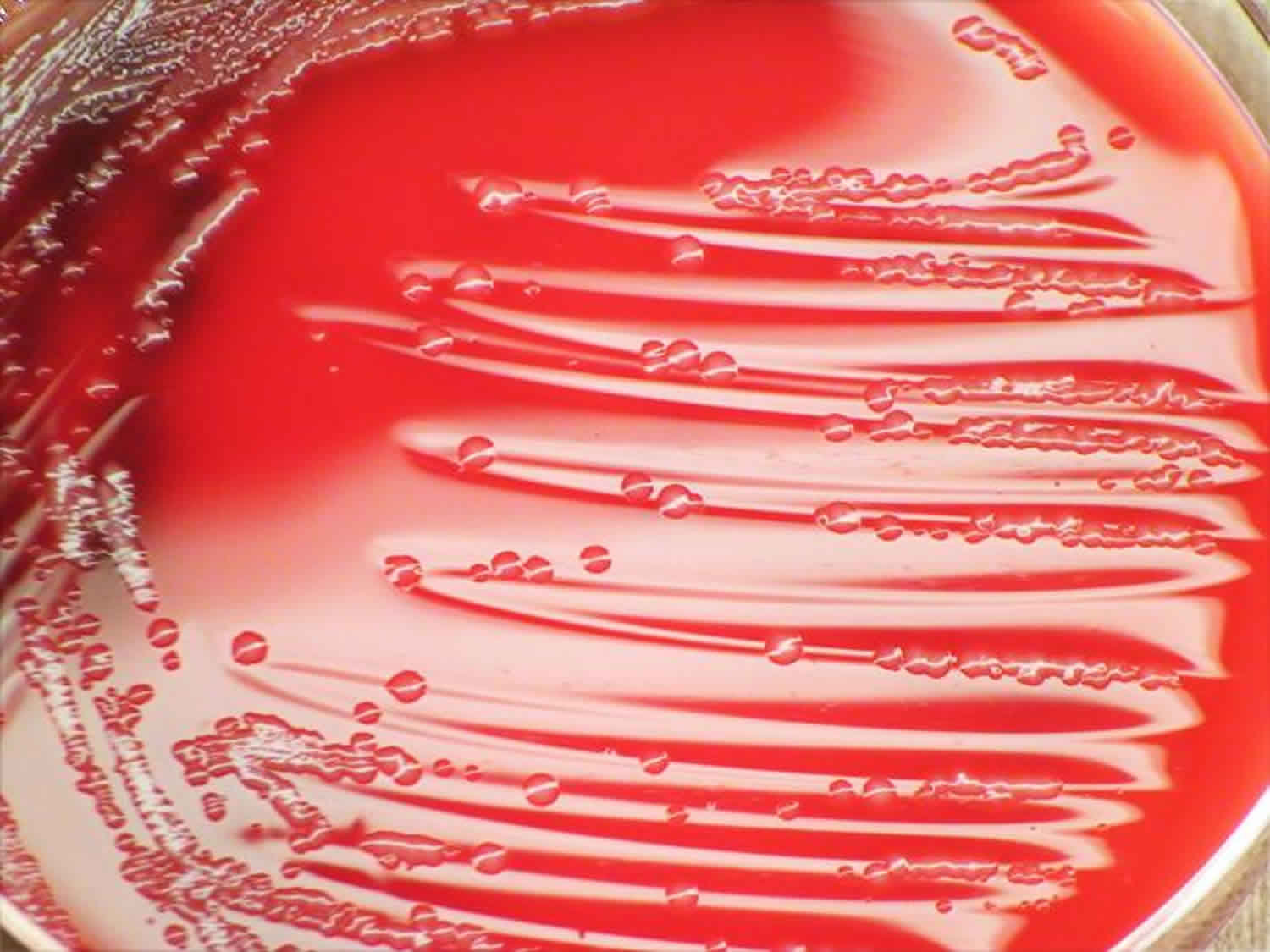

Identification of Morganella morganii is made by recovery of small oxidase-negative catalase and indole-positive gram-negative rods on blood agar or MacConkey agar.

Morganella morganii ferments glucose and mannose but not lactose.

Morganella morganii is motile, facultatively anaerobic, and nonencapsulated, and it hydrolyzes urease and reduces nitrates.

Unlike Proteus species, swarming does not occur.

Morganella morganii urinary tract infections are often associated with an alkaline urine pH.

Morganella morganii treatment

Morganella morganii strains are naturally resistant to penicillin, ampicillin, ampicillin/sulbactam, oxacillin, first-generation and second-generation cephalosporins, erythromycin, tigecycline, colistin, and polymyxin B.

Most strains are naturally susceptible to piperacillin, ticarcillin, mezlocillin, third-generation and fourth-generation cephalosporins, carbapenems, aztreonam, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and chloramphenicol.

The widespread use of third-generation cephalosporins has been associated with the emergence of highly resistant Morganella morganii, as follows:

- Many hospital-acquired strains express derepressed chromosomal ampC beta-lactamases (Bush group 1) similar to those produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter species 31.

- These strains may be resistant to ceftazidime and other third-generation cephalosporins, but they are usually susceptible to cefepime, imipenem, meropenem, piperacillin, the aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones.

- The beta-lactamase inhibitors (ie, clavulanic acid, sulbactam) are ineffective against these enzymes; however, the combination of piperacillin and tazobactam is more effective than piperacillin alone.

- Rare isolates of Morganella morganii produce extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs). These enzymes hydrolyze drugs such as ceftazidime, cefotaxime, and aztreonam but have little effect on the cephamycins (ie, cefoxitin, cefotetan). extended-spectrum beta-lactamases are inhibited by clavulanic acid.

Surgical care

Drain any abscesses. Aggressive surgical drainage is required for brain abscesses caused by Morganella morganii.

Debride any surgical wounds.

Morganella morganii prognosis

Morganella morganii prognosis depends on the type of infection and the particular host.

Data suggest that inappropriate antimicrobials (ones that an organism is resistant to) are associated with a worse outcome.

References- Classification, identification, and clinical significance of Proteus, Providencia, and Morganella. O’Hara CM, Brenner FW, Miller JM. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000 Oct; 13(4):534-46.

- Genome-based phylogeny and taxonomy of the ‘Enterobacteriales’: proposal for Enterobacterales ord. nov. divided into the families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae fam. nov., Pectobacteriaceae fam. nov., Yersiniaceae fam. nov., Hafniaceae fam. nov., Morganellaceae fam. nov., and Budviciaceae fam. nov. Adeolu M, Alnajar S, Naushad S, S Gupta R. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016 Dec; 66(12):5575-5599.

- Tucci V, Isenberg HD. Hospital cluster epidemic with Morganella morganii. J Clin Microbiol. 1981 Nov. 14(5):563-6.

- McDermott C, Mylotte JM. Morganella morganii: epidemiology of bacteremic disease. Infect Control. 1984 Mar. 5(3):131-7.

- Kwon OY, Lee JS, Choi HS, Hong HP, Ko YG. Infected abdominal aortic aneurysm due to Morganella morganii: CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2011 Feb. 36(1):83-5.

- Whole-genome sequencing and identification of Morganella morganii KT pathogenicity-related genes. Chen YT, Peng HL, Shia WC, Hsu FR, Ken CF, Tsao YM, Chen CH, Liu CE, Hsieh MF, Chen HC, Tang CY, Ku TH. BMC Genomics. 2012; 13 Suppl 7():S4.

- Morganella morganii, subspecies morganii, biogroup A: An unusual causative pathogen of brain abscess. Patil AB, Nadagir SD, Lakshminarayana S, Syeda FM. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012 Sep; 3(3):370-2.

- Multiple Liver Abscesses due to Morganella morganii. Ponte A, Costa C. Acta Med Port. 2015 Jul-Aug; 28(4):539.

- Morganella morganii, a non-negligent opportunistic pathogen. Liu H, Zhu J, Hu Q, Rao X. Int J Infect Dis. 2016 Sep; 50():10-7.

- CAPD-related peritonitis caused by Morganella morganii. Tsai MT, Yeh JT, Yang WC, Wu TH. Perit Dial Int. 2013 Jan-Feb; 33(1):104-5.

- Morganella morganii Pericarditis in a Patient with Multiple Myeloma. Nakao T, Yoshida M, Kanashima H, Yamane T. Case Rep Hematol. 2013; 2013():452730.

- Chronic Morganella morganii arthritis in an elderly patient. Schonwetter RS, Orson FM. J Clin Microbiol. 1988 Jul; 26(7):1414-5.

- Fatal Rhabdomyolysis Caused by Morganella morganii in a Patient with Multiple Myeloma. Imataki O, Uemura M. Intern Med. 2017; 56(3):369-371.

- Necrotizing fasciitis following venomous snakebites in a tertiary hospital of southwest Taiwan. Tsai YH, Hsu WH, Huang KC, Yu PA, Chen CL, Kuo LT. Int J Infect Dis. 2017 Oct; 63():30-36.

- Bilateral Morganella Morganii keratitis in a patient with facial topical corticosteroid-induced rosacea-like dermatitis: a case report. Zhang B, Pan F, Zhu K. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017 Jun 28; 17(1):106.

- Neonatal Sulfhemoglobinemia and Hemolytic Anemia Associated With Intestinal Morganella morganii. Murphy K, Ryan C, Dempsey EM, O’Toole PW, Ross RP, Stanton C, Ryan CA. Pediatrics. 2015 Dec; 136(6):e1641-5.

- Fatal Morganella morganii bacteraemia in a diabetic patient with gas gangrene. Ghosh S, Bal AM, Malik I, Collier A. J Med Microbiol. 2009 Jul; 58(Pt 7):965-7.

- Clinical manifestations, risk factors and prognosis of patients with Morganella morganii sepsis. Erlanger D, Assous MV, Wiener-Well Y, Yinnon AM, Ben-Chetrit E. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2019 Jun; 52(3):443-448.

- Clinical complications of urinary catheters caused by crystalline biofilms: something needs to be done. Stickler DJ. J Intern Med. 2014 Aug; 276(2):120-9.

- Ranu SS, Valencia GB, Piecuch S. Fatal early onset infection in an extremely low birth weight infant due to Morganella morganii. J Perinatol. 1999 Oct-Nov. 19(7):533-5.

- Verboon-Maciolek M, Vandertop WP, Peters AC, et al. Neonatal brain abscess caused by Morganella morgagni. Clin Infect Dis. 1995 Feb. 20(2):471.

- Krebs VL, Koga KM, Diniz EM. Necrotizing fasciitis in a newborn infant: a case report. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 2001 Mar-Apr. 56(2):59-62.

- Gautam V, Gupta V, Joshi RM, et al. Morganella morganii-associated arthritis in a diabetic patient. J Clin Microbiol. 2003 Jul. 41(7):3451.

- Jorge MT, Ribeiro LA, da Silva ML, et al. Microbiological studies of abscesses complicating Bothrops snakebite in humans: a prospective study. Toxicon. 1994 Jun. 32(6):743-8.

- Lopez-Sabater EI, Rodriguez-Jerez JJ, Hernandez-Herrero M, et al. Incidence of histamine-forming bacteria and histamine content in scombroid fish species from retail markets in the Barcelona area. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996 Jan. 28(3):411-8.

- Mastroianni A, Coronado O, Chiodo F. Morganella morganii meningitis in a patient with AIDS. J Infect. 1994 Nov. 29(3):356-7.

- Arranz-Caso JA, Cuadrado-Gomez LM, Romanik-Cabrera J, et al. Pyomyositis caused by Morganella morganii in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1996 Feb. 22(2):372-3.

- Chen HW, Lin TY. Tumor abscess formation caused by Morganella morganii complicated with bacteremia in a patient with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011 Sep 14.

- Abdalla J, Saad M, Samnani I, et al. Central nervous system infection caused by Morganella morganii. Am J Med Sci. 2006 Jan. 331(1):44-7.

- Pomeranz A, Korzets Z, Eliakim A, et al. Relapsing Henoch-Schonlein purpura associated with a tubo-ovarian abscess due to Morganella morganii. Am J Nephrol. 1997. 17(5):471-3.

- Choi SH, Lee JE, Park SJ, et al. Emergence of antibiotic resistance during therapy for infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae producing AmpC beta-lactamase: implications for antibiotic use. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008 Mar. 52(3):995-1000.