What is nevus comedonicus

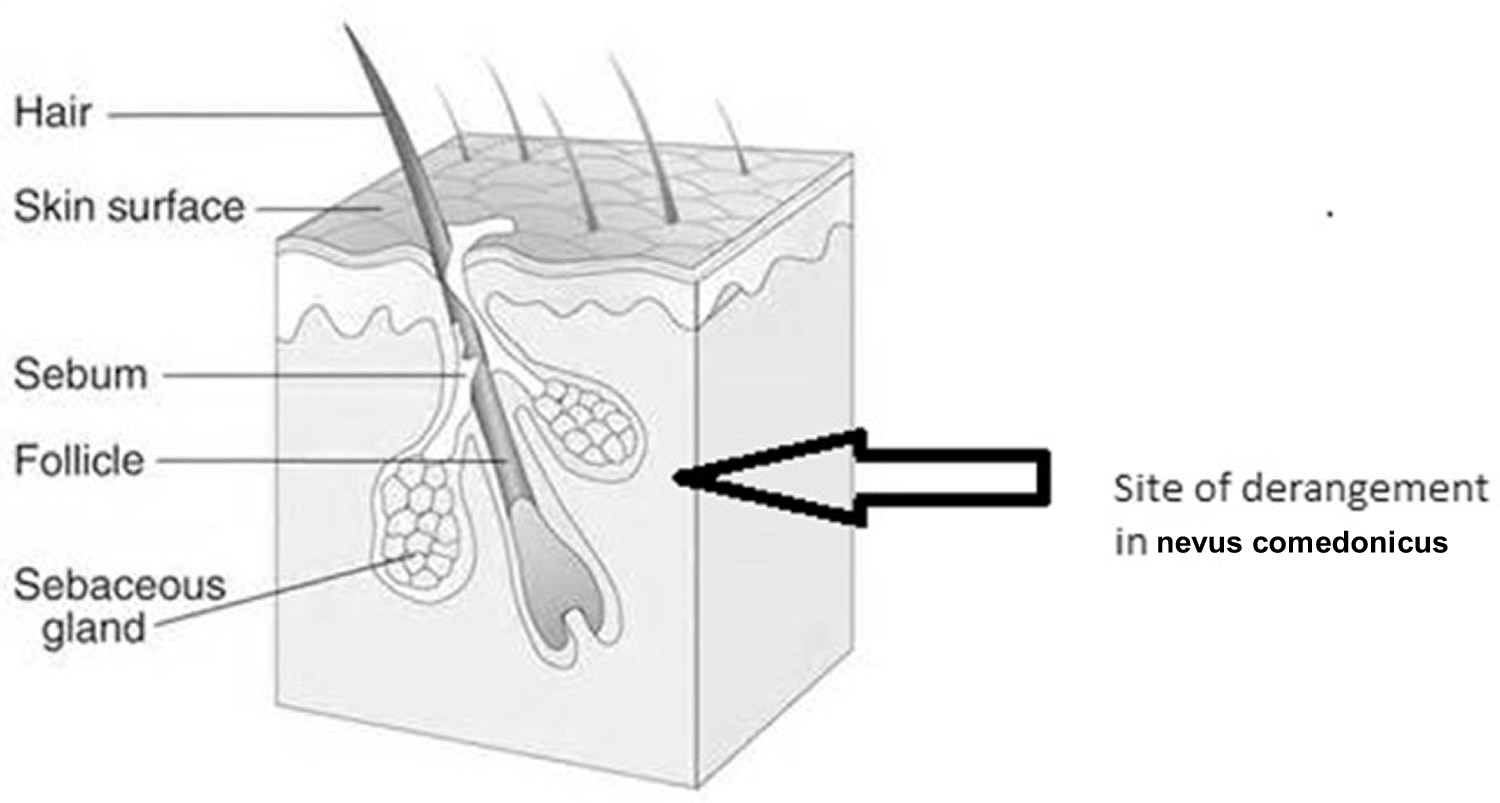

Nevus comedonicus was initially named “comedo nevus”, is a very rare skin abnormality of the pilosebaceous unit (a pilosebaceous hamartoma), which is congenital in most patients but may also appear early in childhood 1. Nevus comedonicus may be localized or have an extensive involvement, the latter showing a unilateral predominance with only a few cases presenting bilaterally. Nevus comedonicus is characterized by the occurrence of dilated, comedo-like openings, typically on the face, neck, upper arms, chest or abdomen. This manifests clinically as giant “blackheads” in the affected areas. The deranged anatomy of the pilosebaceous unit (Figure 1) results in an increased incidence of secondary infections; localized lesions can be observed, unless they lead to secondary complications or are cosmetically unacceptable. Extensive nevus comedonicus can be associated with musculoskeletal defects, eye and neurological involvement, which constitutes nevus comedonicus syndrome. Nevus comedonicus has a reported incidence of 1 in 45,000 to 1 in 100,000 2. Uncomplicated nevus comedonicus can be treated with topical keratolytics, diode, erbium laser, and ultrapulse CO2 laser. Surgical excision can be performed to ensure complete removal and nonrecurrence.

Figure 1. Nevus comedonicus pilosebaceous unit derangement

What is nevus comedonicus syndrome?

Nevus comedonicus syndrome refers to nevus comedonicus presenting with extra cutaneous manifestations usually involving the central nervous system, skeletal system, teeth, and eyes. Common central nervous system abnormalities reported include- seizure disorders, delayed mental development, electroencephalogram abnormalities, microcephaly and transverse myelitis. Skeletal abnormalities include syndactyly, supernumerary digits, scoliosis, and spina bifida. The most common ocular manifestation described is a cataract. Oligodontia is the most reported dental abnormality. Nevus comedonicus syndrome is considered to be a part of the epidermal nevus syndrome which covers extra cutaneous manifestations occurring in association with conditions like nevus comedonicus, verrucous epidermal nevus, and nevus sebaceous. The other syndromes considered to be part of the group of epidermal nevus syndromes include Schimmelpenning syndrome, phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica, angora hair nevus syndrome, and Becker nevus syndrome 3.

Like other epidermal naevi, nevus comedonicus is rarely associated with other abnormalities of the cell of origin, the embryonic ectoderm. These may include:

- Cataracts

- Skeletal anomalies especially affecting fingers and toes or the spine

- Developmental delay

Hidradenitis suppurative can occur along with nevus comedonicus. Hidradenitis suppurative-like lesions complicating nevus comedonicus have been described and mechanical stress has been postulated as a trigger for their development. Other rare systemic associations reported with nevus comedonicus include Alagille syndrome, spinal dysraphism, hypothyroidism, and Paget bone disease. Primary dermatological conditions occurring in association with nevus comedonicus include basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, linear morphea, lichen striatus, accessory breast tissue, epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, nevoid hyperkeratosis of areola, hidradenoma papilliform, syringocystadenoma papilliform, epidermoid cysts, cutaneous horns, hemangiomas, ichthyosis, leukoderma, pilar sheath tumor, dilated pore of Winer, trichoepithelioma, and other epidermal nevi 4.

What causes a nevus comedonicus?

The exact cause of nevus comedonicus is unknown, but it is thought to be due to cutaneous mosaicism; that is, a line of cells with a genetic error. If this error occurs early in the development of the embryo, the cells may spread out to cause multiple comedo naevi.

Mutations in Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2 (FGFR2) along with increased expression of interleukin-1-alpha is considered an important factor in the pathogenesis have been detected in the nevus comedonicus of some patients 5. FGFR2 is the same gene that has found to be abnormal in a more generalised severe genetic condition, Apert syndrome, so the nevus comedonicus may be a ‘mosaic’ of Apert syndrome (some cells have the abnormal gene, and other cells have the normal gene). Apert syndrome causes craniofacial dysostosis (abnormalities of the bone structure of the skull and face) and other skeletal abnormalities. Patients with Apert syndrome often suffer from severe acne, which also arises within a nevus comedonicus.

Other possible factors include gamma-secretase and filaggrin. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of somatic mutations in NEK 9 in nevus comedonicus. NEK9 has been postulated to be important in the regulation of follicular homeostasis. The NEK 9 mutations are associated with increased phosphorylation at Thr210, indicating activation of NEK9 associated kinase. The formation of the comedones in nevus comedonicus also has been associated with other changes such as loss of markers of follicular differentiation and ectopic expression of keratin 10. A recent study has suggested a role for upregulation of ABCA 12 in nevus comedonicus 6.

Nevus comedonicus signs and symptoms

Nevus comedonicus develops shortly after birth in about half of patients, and most patients develop the lesions before the age of ten years 5. Males and females are equally likely to be affected. Lesions often grow more quickly at puberty. They can appear anywhere on the body but are most commonly found on the face, trunk, neck and upper extremities.

The lesions appear as closely grouped slightly elevated papules with central keratinous plugs, so they look like comedones. They may be distributed in a linear, interrupted, unilateral or bilateral pattern and sometimes follow the lines of Blaschko.

Nevus comedonicus usually remains asymptomatic and can increase in the size or distribution during puberty under the influence of hormones 7. Two forms of nevus comedonicus have been described, of which the most commonly encountered is the noninflammatory type that resembles acne-like comedonal eruptions. The inflammatory type, which is not as common, presents with cysts, pustules, fistulae, and abscesses 8.

Extensive nevus comedonicus can be an associated cutaneous feature of the nevus comedonicus syndrome, which involves neurological, skeletal, and ophthalmological defects. The common symptoms include seizures, paresis, EEG abnormalities, polydactyly, limb defects, and cataracts 9. Hence, all patients presenting with extensive distribution of nevus comedonicus should undergo thorough systemic examination and necessary investigations to rule out the syndrome, minimizing significant morbidity.

Nevus comedonicus complications

Rarely, at puberty or later, a nevus comedonicus may develop inflammatory acne-like lesions within it. These can lead to cysts, recurrent bacterial infections, abscesses, and scarring. These should be treated with appropriate antibiotics or surgical drainage. Topical and oral treatment for acne may improve the appearance.

Nevus comedonicus diagnosis

Nevus comedonicus diagnosis is usually clinical. Detailed evaluation of the central nervous system, skeletal system, and the eyes is required in suspected cases of nevus comedonicus syndrome. A skin biopsy shows the typical dilated follicular ostia filled with keratin. Immunohistochemistry studies have shown an increased expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), HLA-DR, and CD68. Electron microscopy has shown an increased number of Langerhans cells. Usually the clinical diagnosis is quite obvious with the history of early age of onset and the typical morphology, but in case of atypical presentations other conditions to consider as differentials include atypical acne (e.g., segmental acne and other mosaic acneiform conditions), other acneiform conditions such as chloracne, Favre- Racouchot syndrome (i.e., nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones), and familial dyskeratotic comedones. This last is a relatively rare, autosomal dominantly inherited condition characterized by hyperkeratotic, comedonal lesions. Histological examination shows comedones with associated dyskeratosis 10.

Recently, dermoscopy has been reported to be useful in the diagnosis of nevus comedonicus. Dermoscopy highlights the typical comedonal lesions. The typical dermoscopy findings described include multiple light and dark brown, circular or barrel shaped homogenous areas with prominent keratin plugs 11.

Nevus comedonicus treatment

There is no specific treatment for nevus comedonicus. Lesions are usually symptomless, and treatment is usually sought for cosmetic purposes.

Localized uncomplicated nevus comedonicus can be treated with comedo extraction, dermabrasion, superficial shaving, and topical keratolytics such as urea, tazarotene, retinoids, salicylic acid, calcipotriene, and ammonium lactate 12 with varying degrees of improvement, but the high recurrence rate has made topical management unpopular.

Diode laser and ablative lasers such as erbium, neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet, and ultrapulse CO2 lasers have been successfully used in a few nevus comedonicus cases and ultrapulse CO2 laser has been found to be more effective than other lasers, owing to its deeper penetration 13.

Surgery and laser treatment may be used if lesions are particularly disfiguring. Surgical excision with primary closure and reconstruction with tissue expander have been tried for treatment of nevus comedonicus lesions with good, aesthetic results 14. Extensive lesions with secondary complications, require staged surgical excision and resurfacing, and tissue defects can be effectively reconstructed with flaps and skin grafting. The local flap in the axilla provided good soft-tissue padding, enabling unrestricted arm movements.

References- Extensive Nevus Comedonicus, Complicated with Recurrent Abscesses, Successfully Treated with Surgical Resurfacing. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2018 Jan-Mar; 11(1): 33–37. doi: 10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_122_17 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5921448

- Nevus comedonicus. A review of the literature and report of twelve cases. Nabai H, Mehregan AH. Acta Derm Venereol. 1973; 53(1):71-4.

- Tchernev G, Ananiev J, Semkova K, Dourmishev LA, Schönlebe J, Wollina U. Nevus comedonicus: an updated review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2013 Jun;3(1):33-40.

- Ravaioli GM, Neri I, Zannetti G, Patrizi A. Congenital nevus comedonicus complicated by a hidradenitis suppurativa-like lesion: Report of a childhood case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Sep;35(5):e298-e299

- Kaliyadan F, Ashique KT. Nevus Comedonicus. [Updated 2019 Jun 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441903

- Liu F, Yang Y, Zheng Y, Liang YH, Zeng K. Mutation and expression of ABCA12 in keratosis pilaris and nevus comedonicus. Mol Med Rep. 2018 Sep;18(3):3153-3158.

- Grimalt R, Caputo R. Posttraumatic nevus comedonicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:273–4.

- Kim YJ, Hong CY, Lee JR. Nevus comedonicus with multiple cysts. J Korean Cleft Palate Craniofac Assoc. 2009;10:135–7.

- Patrizi A, Neri I, Fiorentini C, Marzaduri S. Nevus comedonicus syndrome: A new pediatric case. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15:304–6.

- Cho SB, Oh SH, Lee JH, Bang D, Bang D. Ultrastructural features of nevus comedonicus. Int. J. Dermatol. 2012 May;51(5):626-8.

- Vora RV, Kota RS, Sheth NK. Dermoscopy of Nevus Comedonicus. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017 Sep-Oct;8(5):388-389.

- Milburn S, Whallett E, Hancock K, Munnoch DA, Stevenson JH. The treatment of naevus comedonicus. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57:805–6.

- Givan J, Hurley MY, Glaser DA. Nevus comedonicus: A novel approach to treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:721–5.

- Arora R, Nagarkar NM, Prabha N, Hussain N. Nevus comedonicus associated with epidermoid cyst. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2016;17:277–9.