Nose cauterization

Nose cauterization also called nasal cauterization or nasal cautery, is a type of procedure where a chemical (silver nitrate) or electrical device (electrocoagulation) is applied to the mucous membranes in the nose to stop nose bleeds (epistaxis). Before starting the procedure, a vasoconstrictor and local anesthetic should be applied 1. Nose cauterization seals the blood vessels and builds scar tissue to help prevent more bleeding. Nose cauterization can be performed in your ENT doctor’s clinic procedure room with topical anesthetic or can be performed in an operating room under general anesthesia. Sometimes this procedure is performed in conjunction with other procedures to improve nasal breathing (i.e., sinus surgery, nasal endoscopy, nasal cautery or septoplasty).

A Swiss retrospective study showed that in terms of therapeutic success, electrocoagulation was superior to chemical coagulation (88% versus 78%) (failure rate 12% versus 22%) 2. A US study of children treated intraoperatively by these same two methods for recurrent anterior epistaxis also found a lower recurrence rate for electrocoagulation than for chemical cauterization during the 2-year period after the procedure (recurrence events 2% versus 18%) 3. Chemical cautery is described as simpler to use, cheaper, and more widely available 4.

The nasal cauterization procedure usually takes about 5-10 minutes, but can take longer depending on the severity and any additional combined procedures planned. Your surgeon provides an idea of how much time is expected, but this may change during the procedure. If done awake in the office, topical anesthetics and decongestants are typically used to decrease discomfort.

Before and after surgery: a pediatric nurse prepares the child for the procedure, assists the pediatric ENT surgeon during the procedure, and cares for the child after the procedure.

Anesthesiology: If the procedure takes place in the operating suite, the child is placed under general anesthesia by a pediatric anesthesiologist. It is important that the parent meet with the anesthesiologist prior to the procedure.

Surgery: A ENT surgeon may use specialized telescopes to systematically evaluate the nasal airway in conjunction with specialized nasal instruments. If additional procedures are needed, additional special instruments may be used to perform these procedures.

After the nose cauterization, your nose will be packed with a special sponge and polysporin to protect it while it heals. After the nose cauterization procedure, you may feel itching and pain in your nose for 3 to 5 days. You may feel like you want to touch, scratch, or pick at the inside of your nose. But doing this may cause more nosebleeds. Tylenol or ibuprofen is typically appropriate for pain control. Sometimes stronger narcotic pain medications may be prescribed for additional pain control. Typically frequent use of topical moisturizing and/or antibiotic ointment in the nose is recommend after the procedure. This helps healing and decreases crusting.

You will feel congested and may have difficulty breathing through your nose for about a week after the procedure. For a week after nose cauterization you must not blow your nose, pick your nose, bend over or lift anything heavy, or take part in any activity that requires a lot of energy.

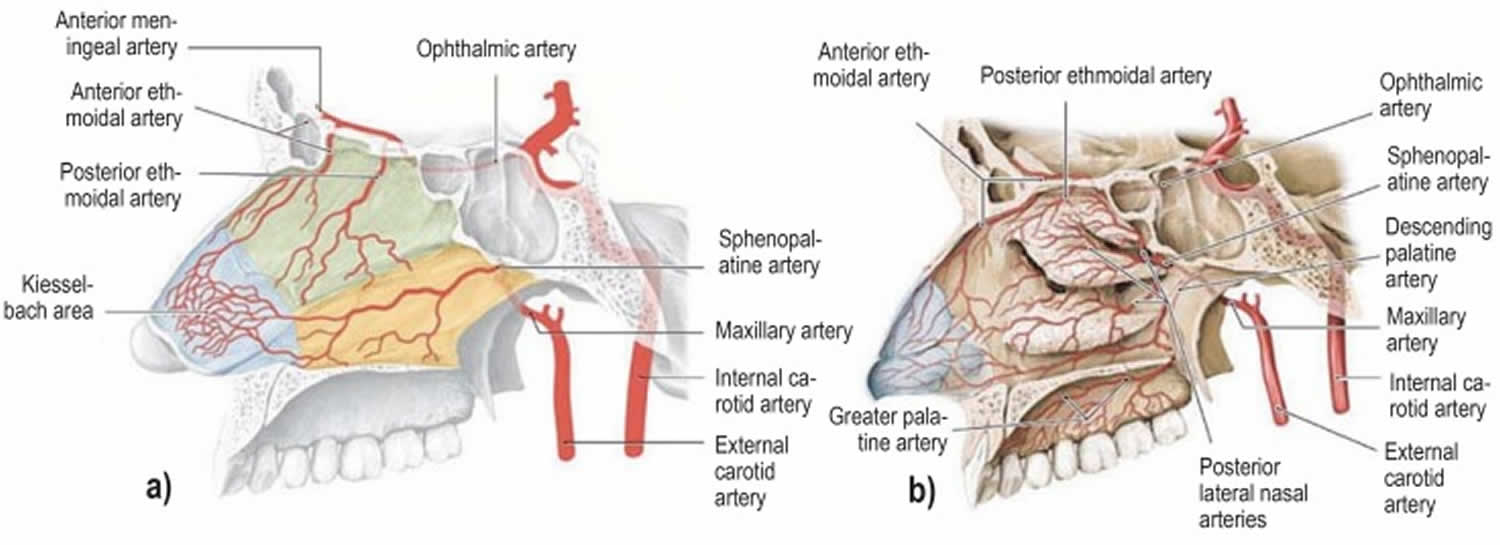

Figure 1. Arteries involve in nose bleeds (nasal septum)

Figure 2. Arterial supply of the nasal cavity

Footnote: The different territories supplied by the internal carotid artery (green) and the external carotid artery (yellow) are indicated in a). The Kiesselbach area (blue) is supplied by branches of both the main arteries (red).

a) Arteries supplying the nasal septum and b) the lateral walls of the nasal cavity.

[Source 5 ]How can you care for yourself at home after nose cauterization?

Nose care

- Don’t touch the part of your nose that was treated.

- Try not to bump your nose.

- To avoid irritating your nose, do not blow your nose for 2 weeks. Gently wipe it one nostril at a time.

- If you get another nosebleed:

- Sit up and tilt your head slightly forward. This keeps blood from going down your throat.

- Use your thumb and index finger to pinch your nose shut for 10 minutes. Use a clock. Do not check to see if the bleeding has stopped before the 10 minutes are up. If the bleeding has not stopped, pinch your nose shut for another 10 minutes.

- Apply antibacterial ointment or saline nasal spray to the inside of your nose several times a day for 10 days. This will help keep the area moist.

Medicines

- Your doctor will tell you if and when you can restart your medicines. He or she will also give you instructions about taking any new medicines.

- If you take blood thinners, such as warfarin (Coumadin), clopidogrel (Plavix), or aspirin, be sure to talk to your doctor. He or she will tell you if and when to start taking those medicines again. Make sure that you understand exactly what your doctor wants you to do.

- Be safe with medicines. Read and follow all instructions on the label.

- If the doctor gave you a prescription medicine for pain, take it as prescribed.

- If you are not taking a prescription pain medicine, ask your doctor if you can take an over-the-counter medicine.

- Avoid aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and naproxen (Aleve) while your nose is healing. They can increase the risk of bleeding.

Activity

- For the first 2 to 3 hours after the procedure:

- Don’t bend over or lift anything heavy.

- Avoid heavy exercise or activity.

- You can do your normal activities when it feels okay to do so.

Be sure to make and go to all appointments, and call your doctor if you are having problems. It’s also a good idea to know your test results and keep a list of the medicines you take.

When should you call for help?

Call your doctor or seek immediate medical care if:

- You have pain that does not get better after you take pain medicine.

- You get another nosebleed and your nose is still bleeding after you have pinched your nose shut 3 times for 10 minutes each time (30 minutes total).

- There is a lot of blood running down the back of your throat even after you pinch your nose and tilt your head forward.

- You have a fever.

Watch closely for any changes in your health, and be sure to contact your doctor if:

- You still get nosebleeds often, even if they don’t last long.

- You do not get better as expected.

What is nose bleeds

A nose bleed also called epistaxis, is loss of blood from the tissue lining your nose. Bleeding most often occurs in one nostril only. Nosebleeds are very common. Most nosebleeds occur because of minor irritations, after an injury or colds. Most nosebleeds are mild and do not last long. Nose bleeds are common in children and older people with medical conditions.

Although nose bleeds can be scary, they’re generally only a minor annoyance and aren’t dangerous. Frequent nosebleeds are those that occur more than once a week.

In the United States, one of every seven people will develop a nosebleed some time in their lifetime. Nosebleeds can occur at any age but are most common in children aged 2-10 years and adults aged 50-80 years.

Older people and people with medical conditions, such as blood disorders or those taking blood-thinning medicines, can also be more likely to experience nosebleeds. In these cases the bleeding can be severe and medical assistance may be needed to stop the bleeding.

In 90% to 95% of cases of nose bleeds (epistaxis), the source of the bleed is in the area on the front part of the nasal septum (anterior nosebleed), the Kiesselbach area (Little’s area) 5 and in 5% to 10% of cases it occurs posteriorly in the posterior region of the nasal cavity 6.

The most frequent cause of nose bleeds (epistaxis) is trauma due to digital manipulation (nose picking) 7. Other causes are listed below. In 2014, a systematic review reported that most studies described raised blood pressure at the time the epistaxis occurred. However, these studies were unable to show hypertension to be an immediate cause of epistaxis. Confounding stress and, possibly, “white coat syndrome” may have contributed to raised arterial blood pressure in the setting of epistaxis 8. In general, nose bleeds are not a symptom or result of high blood pressure. It is possible, but rare, that severe high blood pressure may worsen or prolong bleeding if you have a nosebleed. Several studies have shown a relative increase in nose bleeds (epistaxis) episodes during cold, dry weather or during periods when there are marked variations in air temperature and pressure 9.

Nose bleeds can often occur if you:

- Have allergies, infections, or dryness that cause itching and lead to picking of the nose.

- Pick your nose

- Blow your nose too hard that ruptures superficial blood vessels

- Strain too hard on the toilet

- Have an infection in the nose, throat or sinuses

- Low humidity or irritating fumes: If your house is very dry, or if you live in a dry climate, the lining of your child’s nose may dry out, making it more likely to bleed. If he is frequently exposed to toxic fumes (fortunately, an unusual occurrence), they may cause nosebleeds, too.

- Receive a bump, knock or blow to the head or face

- Have a cold

- Have a bunged-up or stuffy nose from an allergy.

- Anatomical problems: Any abnormal structure inside the nose can lead to crusting and bleeding (e.g., deviated septum)

- Are taking some types of medicines, such as anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin) or anti-inflammatories (e.g., aspirin) or nose sprays

- Clotting disorders that run in families or are due to medications.

- Fractures of the nose or the base of the skull. Head injuries that cause nosebleeds should be regarded seriously.

- Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, a disorder involving a blood vessel growth similar to a birthmark in the back of the nose.

- Tumors, both malignant and nonmalignant, have to be considered, particularly in the older patient or in smokers.

Other causes of nose bleeds:

- Traumatic

- Digital manipulation (nose picking)

- Nasal fracture/contusion

- Foreign body in the nose

- Iatrogenic (e.g., nasogastric tube, surgical interventions)

- Neoplastic

- Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma

- Tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses

- Hematological

- Thrombocytopenia

- Hemophilia A and B

- Von Willebrand disease

- Liver failure

- Structural

- Mucosal dryness

- Septal perforation

- Osler–Weber–Rendu disease (hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia)

- Drug-related

- Anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs

- Glucocorticoid nasal sprays

- Nasal consumption of drugs

- Inflammatory

- Allergic rhinitis

- Acute infectious diseases

How do I stop a nosebleed?

- Stay calm, or help a young child stay calm. A person who is agitated may bleed more profusely than someone whos been reassured and supported.

- Keep head higher than the level of the heart. Sit up.

- Sit down and lean slightly forward so the blood wont drain in the back of the throat.

- Gently blow any clotted blood out of the nose.

- Using the thumb and index finger, pinch all the soft parts of the nose. Do not pack the inside of the nose with gauze or cotton.

- Hold the position for five to ten minutes. If its still bleeding, hold it again for an additional 10 to 15 minutes.

Once the bleeding has stopped, encourage your child not to blow or pick his nose for about 24 hours. This will help the blood clot in his nose to strengthen.

Your child might vomit during or after a nosebleed if she has swallowed some blood. This is pretty normal, and your child should spit out the blood.

When the nose bleed won’t stop

If you can’t stop the bleeding with the treatment steps above, you should take your child to the doctor or hospital emergency department.

The doctor might put some cream or ointment up your child’s nose to help stop the bleeding.

Another treatment can involve nose-packing. This is where the doctor puts a special cloth dressing into your child’s nose. Your child will need a follow-up appointment 24-48 hours later to have the dressing taken out.

Cautery is another common treatment. This is where a special chemical is used to seal off the bleeding and ‘freeze’ the blood vessel. Doctors usually use anaesthetic for cautery.

Very rarely your child might need to see an ear, nose and throat specialist and go into hospital for treatment.

After a bleeding nose

Here’s what to do after your child has had a bleeding nose:

- Ensure your child rests over the next 24 hours.

- Keep your child out of hot baths.

- Encourage your child not to pick or blow her nose.

Sometimes a doctor will recommend that your child uses a saline nasal spray or lubricating ointment to help with dryness. The doctor might also recommend using an antibiotic ointment, which you’ll need to put up your child’s nose.

Most nosebleeds aren’t serious and will stop on their own or by following self-care steps.

Seek emergency medical care if nosebleeds:

- Follow an injury, such as a car accident

- Nose bleeding occurs after a head injury. This may suggest a skull fracture, and x-rays should be taken.

- Your nose may be broken (for example, it looks crooked after a hit to the nose or other injury).

- Involve a greater than expected amount of blood.

- Interfere with breathing.

- Last longer than 20 to 30 minutes even with compression.

- Occur in children younger than age 2.

- Your child is generally unwell, looks pale or has unexplained bruises on her body.

- Your child has regular nosebleeds.

Don’t drive yourself to an emergency room if you’re losing a lot of blood. Call your local emergency services number or have someone drive you.

See your doctor if you’re having frequent nosebleeds, even if you can stop them fairly easily. It’s important to determine the cause of frequent nosebleeds.

An ear, nose, and throat specialist (otolaryngologist) will carefully examine the nose using an endoscope, a tube with a light for seeing inside the nose, prior to making a treatment recommendation. Two of the most common treatments are cautery and packing the nose. Cautery is a technique in which the blood vessel is burned with an electric current, silver nitrate, or a laser. Sometimes, a doctor may just pack the nose with a special gauze or an inflatable latex balloon to put pressure on the blood vessel.

Why do people get nose bleeds

The nose is an area of the body that contains many tiny blood vessels (or arterioles) that can break and bleed easily (see Figure 1). Air moving through the nose can dry and irritate the membranes lining the inside of the nose. Crusts can form that bleed when irritated. Nosebleeds occur more often in the winter, when cold viruses are common and indoor air tends to be drier.

Nosebleeds are divided into two types, depending on whether the bleeding is coming from the front or back of the nose.

Most nosebleeds occur on the front of the nasal septum (anterior nosebleed). This is the piece of the tissue that separates the two sides of the nose. This type of nosebleed can be easy for a trained professional to stop. Less commonly, nosebleeds may occur higher on the septum or deeper in the nose such as in the sinuses or the base of the skull. Such nosebleeds may be harder to control. However, nosebleeds are rarely life threatening.

What is an anterior nosebleed?

Most nosebleeds (or epistaxes) begin in the lower part of the septum, the semi-rigid wall that separates the two nostrils of the nose. The septum contains blood vessels that can be broken by a blow to the nose or the edge of a sharp fingernail. Nosebleeds coming from the front of the nose, (anterior nosebleeds) often begin with a flow of blood out one nostril when the patient is sitting or standing.

Anterior nosebleeds are common in dry climates or during the winter months when dry, heated indoor air dehydrates the nasal membranes. Dryness may result in crusting, cracking, and bleeding. This can be prevented by placing a light coating of petroleum jelly or an antibiotic ointment on the end of a fingertip and then rubbing it inside the nose, especially on the middle portion of the nose (the septum).

What is a posterior nosebleed?

More rarely, a nosebleed can begin high and deep within the nose and flow down the back of the mouth and throat, even if the patient is sitting or standing.

Obviously, when lying down, even anterior (front of nasal cavity) nosebleeds may seem to flow toward the back of the throat, especially if coughing or blowing the nose. It is important to try to make the distinction between the anterior and posterior nosebleed, since posterior nosebleeds are often more severe and almost always require a physicians care. Posterior nosebleeds are more likely to occur in older people, persons with high blood pressure, and in cases of injury to the nose or face.

Recurring nosebleeds

Recurring nosebleeds can be a nuisance, but are usually nothing to worry about. However, you should discuss it with your doctor as they may want to investigate that there is no underlying medical condition which is causing the bleeds.

If your nosebleeds persist and become a problem, you may need treatment, such as surgery to cauterize (burn) the blood vessels in the nose. Talk to your doctor about your options.

Nose cauterization indications

Typically, people who benefit from nose cauterization when they have recurrent nosebleeds. These episodes can occur from a prominent blood vessel in their nose that bleeds from trauma (nose picking, rubbing nose, or bumping nose), from drying (dessication) of the mucous membranes lining the nose, or from another reason. Certain underlying medical conditions can make people more prone to nosebleeds, including individual or familial bleeding disorders, platelet disorders, cancers or medications used to treat other conditions.

If an underlying medical condition or medication is the cause of the nosebleeds, first attempts are aimed treating or removing these sources of tendency for bleeding.

In addition, nasal creams, ointments, gels (emollients), nasal saline spray and increased environmental humidification can help improve the nosebleeds by decreasing the dryness in the nose. This makes the nose less prone to bleeding.

Avoidance of trauma (nose picking, manipulation), especially in young children, is important.

If nosebleeds continue despite these attempts, nose cauterization may be recommended.

What can cause nose bleeds

The two most common causes of nosebleeds are:

- Dry air — when your nasal membranes dry out, they’re more susceptible to bleeding and infections

- Nose picking

Other causes of nose bleeds include:

- Acute sinusitis (sinus infection)

- Allergies

- Aspirin use

- Bleeding disorders, such as hemophilia

- Blood thinners (anticoagulants), such as warfarin and heparin

- Blowing the nose very hard, or picking the nose

- Chemical irritants, such as ammonia, including medicines or drugs that are sprayed or snorted

- Chronic sinusitis

- Cocaine use

- Common cold

- Deviated septum

- Foreign body in the nose

- Irritation due to allergies, colds, sneezing or sinus problems

- Nasal sprays, such as those used to treat allergies, if used frequently

- Nonallergic rhinitis (chronic congestion or sneezing not related to allergies)

- Overuse of decongestant nasal sprays

- Oxygen treatment through nasal cannulas

- Trauma to the nose, including a broken nose, or an object stuck in the nose

- Very cold or dry air

Less common causes of nosebleeds include:

- Alcohol use

- Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

- Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)

- Leukemia

- Nasal and paranasal tumors

- Nasal polyps

- Nasal surgery

- Pregnancy

- Sinus or pituitary surgery (transsphenoidal)

Repeated nosebleeds may be a symptom of another disease such as high blood pressure, a bleeding disorder, or a tumor of the nose or sinuses. Blood thinners, such as warfarin (Coumadin), clopidogrel (Plavix), or aspirin, may cause or worsen nosebleeds.

Cauterize nose side effects

Complications of nose cauterization include septal perforation, infection, rhinorrhea, and increased bleeding 7. Bilateral nasal cauterization in the area of the nasal septum should be avoided if possible, as this risks septal perforation 10. There are no published studies on the incidence of septal perforation after cautery 11.

References- Daudia A, Jaiswal V, Jones NS. Guidelines for the management of idiopathic epistaxis in adults: how we do it. Clin Otolaryngol. 2008;33:618–620.

- Soyka MB, Nikolaou G, Rufibach K, Holzmann D. On the effectiveness of treatment options in epistaxis: an analysis of 678 interventions. Rhinology. 2011;49:474–478.

- Johnson N, Faria J, Behar P. A comparison of bipolar electrocautery and ¬chemical cautery for control of pediatric recurrent anterior epistaxis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153:851–856.

- Traboulsi H, Alam E, Hadi U. Changing trends in the management of epistaxis. Int J Otolaryngol. 2015;2015 263987.

- Beck R, Sorge M, Schneider A, Dietz A. Current Approaches to Epistaxis Treatment in Primary and Secondary Care. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(1-02):12–22. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2018.0012 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5778404

- Viehweg TL, Roberson JB, Hudson JW. Epistaxis: diagnosis and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:511–518.

- Morgan DJ, Kellerman R. Epistaxis: evaluation and treatment. Primary Care. 2014;41:63–73.

- Kikidis D, Tsioufis K, Papanikolaou V, Zerva K, Hantzakos A. Is epistaxis associated with arterial hypertension? A systematic review of the literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:237–243.

- Walker TWM, Macfarlane TV, McGarry GW. The epidemiology and chronobiology of epistaxis: an investigation of Scottish hospital admissions 1995-2004. Clin Otolaryngol. 2007;32:361–365.

- Murer K, Soyka MB. Die Behandlung des Nasenblutens [The treatment of ¬epistaxis] Praxis (Bern 1994) 2015;104:953–958.

- Lanier B, Kai G, Marple B, Wall GM. Pathophysiology and progression of nasal septal perforation. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:473–480.