Obturator hernia

Obturator hernia also called ‘the skinny old lady hernia’, is an extremely rare type of hernia that occurs as a result of the protrusion of intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal organs or tissues through the obturator canal 1. This is due to the high incidence of these hernias in women in their seventh or eighth decade, who are normally gaunt 2 and it can almost be said to be found almost exclusively in women 3. As the obturator canal is a small opening in the pelvis, there is an increased propensity for obturator hernias to get incarcerated and subsequently strangulated obturator hernia 4. The incidence of obturator hernia is between 0.04 and 1.4% of all hernias and occurs predominantly in elderly octogenarian patients, malnourished, multiparous, female patients due to a wider pelvis, greater transverse diameter 5. The most significant clinical manifestation of obturator hernia is abdominal pain, vomiting and nausea due to small bowel obstruction 5. Delayed recognition has been related to increased morbidity and mortality 6. The mortality rate of obturator hernia can be as high as 70% due to delayed diagnosis and the need for surgical intervention in these elderly patients with comorbid diseases 7.

Obturator herniation usually occurs on the right side. It is thought that in case involving the left side, the sigmoid colon covers the left obturator foramen and this may prevent hernia formation 8. However, Igari et al 9 reported the incidence of obturator hernia was equal on both sides, Thanapaisan et al 8 reported left hernia are more common than right hernia, with a rate of 3:2. The hernia sac usually contains small bowel, especially ileum; although jejunum, colon, omentum, appendix, Meckel’s diverticulum, ovary, fallopian tube, urinary bladder have all been reported in hernia sac 10.

The diagnosis of an obturator hernia can be difficult, with the late presentation and often poor functional status of the patient 11. A high index of suspicion is required in the elderly population, and even then, diagnosis may not be achieved without imaging or operative findings.

The treatments of obturator hernia are manifold, with multiple reports now available of minimally invasive methods of treating these cases 12. Patient selection is important in all cases, and a swift resolution of the patient state is crucial.

Obturator hernia anatomy

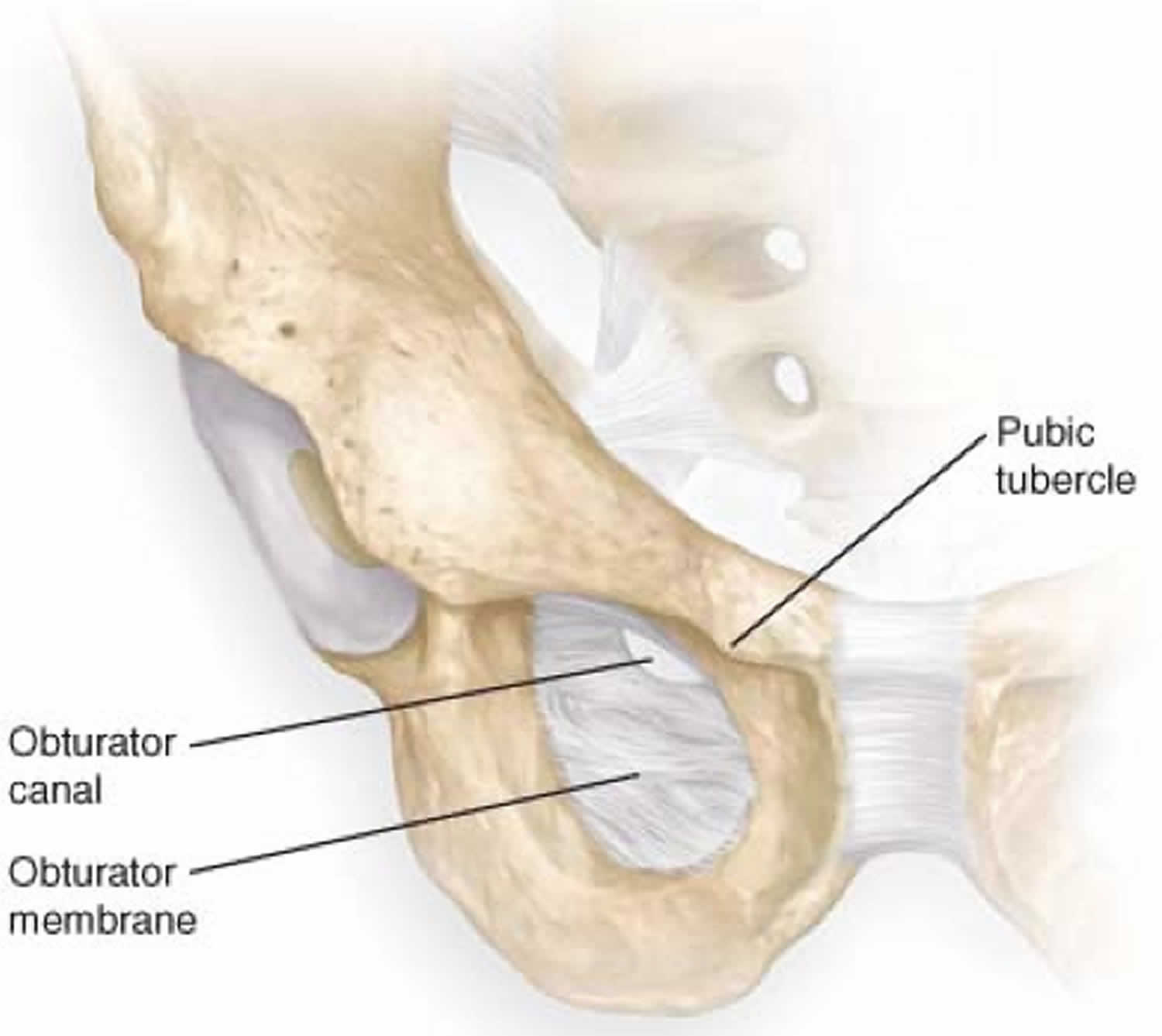

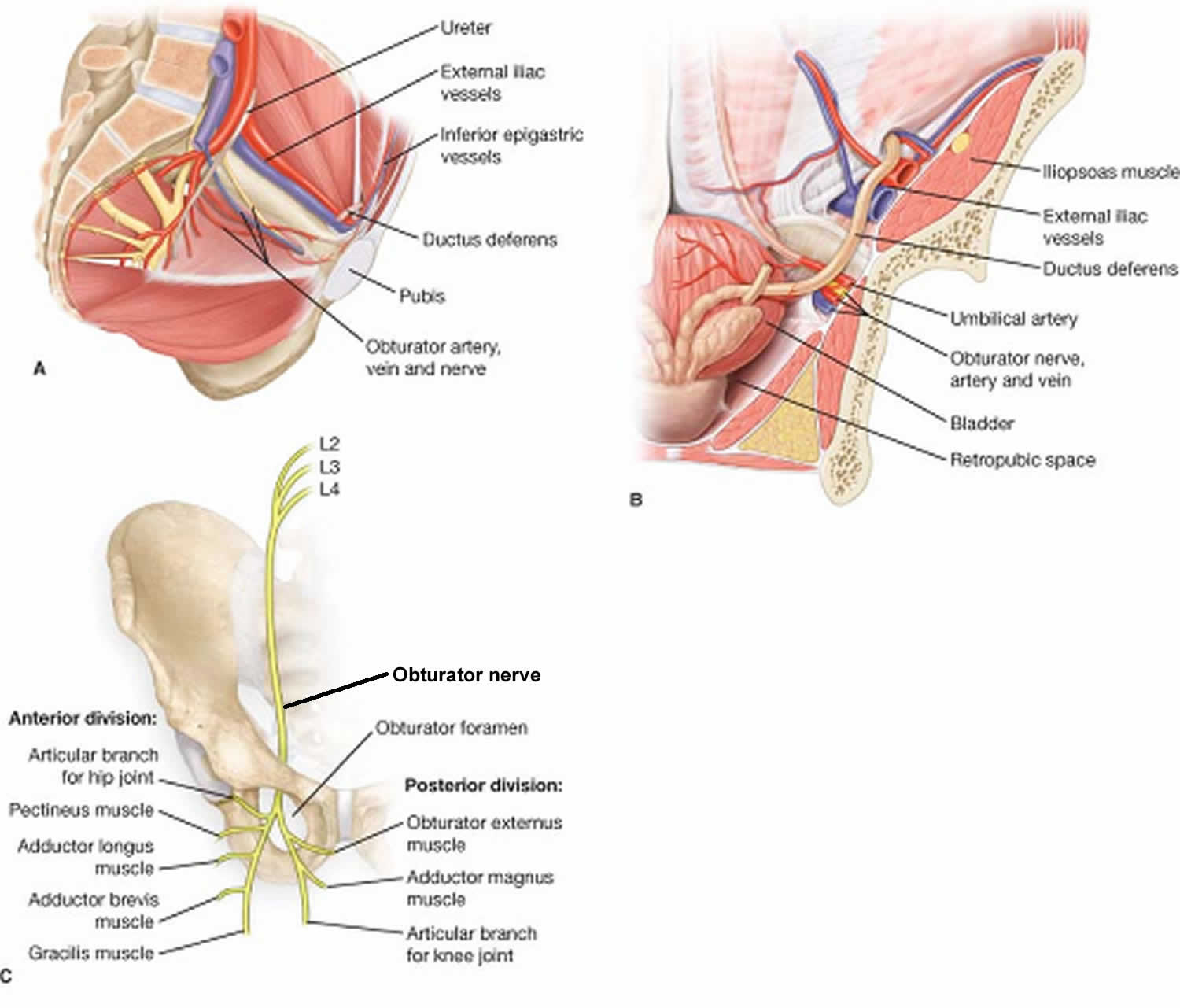

The obturator foramen is an opening in the pelvis created by the ischium and pubis bones. The foramen itself is covered by a quadrella musculoaponeurotic membrane – the obturator membrane. The neurovascular bundle (obturator artery, vein, and nerve) pierces this membrane anterosuperiorly, then passes through the obturator canal. The obturator canal starts as the obturator groove, becoming the obturator canal by a ligamentous band attaching to the posterior and anterior obturator tubercle. This canal connects the pelvis to the medial compartment of the thigh. The obturator canal is about 0.2 to 0.5 cm wide, and 2 to 3cm long 13. The obturator nerve is the most cranial of the neurovascular bundle passing through the canal. It subsequently then divides upon exiting the canal into an anterior and posterior division.

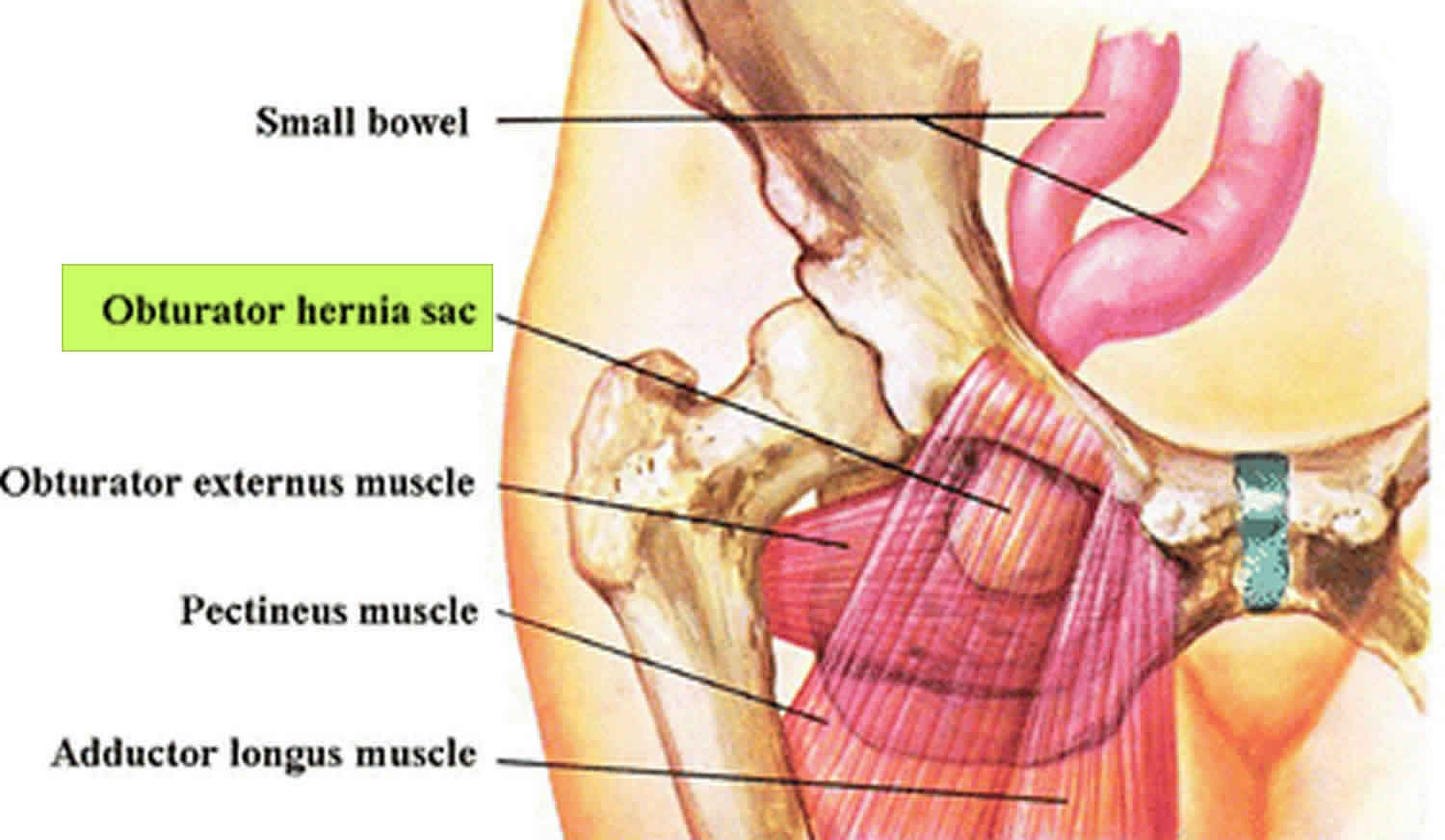

The obturator membrane is covered on either side by the obturator muscles. As such, any hernia that forms will pass through obturator internus, the obturator membrane, and obturator externus in that order. The natural location for the hernial sac to lie after its passage through these structures is deep and inferior to the pectineus muscle, superficial to obturator externus. However, the hernia could protrude through the obturator externus muscle, taking with it the posterior obturator nerve. In this position, the hernial sac lies posterior to the adductor brevis. Very rarely, the hernial sac can be found between the obturator internus and externus muscles.

The obturator foramen has a different shape according to the sex of the individual. Women tend to have triangular, wider foramina, while men tend to have more oval ones.

Figure 1. Obturator foramen

Obturator hernia causes

Obturator hernia is an abdominal hernia generally seen in elderly, scraggy, multiparous woman 9. Obturator hernia has been associated with multiple comorbidities including advanced age, malnutrition, raised intra-abdominal pressure due to ascites, chronic constipation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and kyphoscoliosis 14. Obturator hernia is nine times more common in women than men due to a broader pelvis, a larger obturator canal and history of pregnancy 9. Multiple pregnancies, resulting in increased intra-abdominal pressure, cause weakening of the pelvic peritoneum and obturator membranes, which are prone to hernia development 15. Malnutrition is a predisposing factor due to the decreased preperitoneal fat and lymphatic tissue over the obturator canal which increases the risk of herniation 10. In addition to these risk factors, Mantoo et al 16 reported Asians have been reported to have higher rates of obturator hernia while Western studies indicate a much lower incidence. Obturator herniais generally seen in frail, elderly female patients between 70 and 90 years and has been called “little old lady’s hernia” 16.

Obturator hernia signs and symptoms

Obturator hernia commonly presents with symptoms of intestinal obstruction including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and distention 17. The Howship-Romberg sign causing pain in the medial thigh is pathognomonic for obturator hernia and occurs due to the distribution of the obturator nerve by the pressure of the hernia sac 17. Howship-Romberg sign or obturator neuralgia occurs by the internal rotation of the hip, and the pain is aggravated by lengthening of the thigh, abduction and medial rotation 17. Obturator neuralgia is relieved by flexing the hip. Although Thanapaisan et al 8 reported that 13% of patients had a Howship-Romberg sign, Igari et al 18 reported a 50% positive Howship-Romberg sign.

The Hannington-Kiff sign is an absent adductor reflex in the thigh. This is elicited by placing a finger on the adductors 5 cm above the knee, then percussing said finger with a tendon hammer. A contraction of muscle indicated an adductor reflex that is present. The Hannington-Kiff sign is more specific than the Howship-Romberg sign, but could be hard to elicit, and is operator dependent 19.

Obturator hernias are rarely diagnosed in a non-symptomatic patient, with the majority of cases presenting as an emergency with intestinal obstruction 1. The presentation of a strangulated obturator hernia is rare, with it being less than 0.04% of all hernias 20. However, in an emaciated elderly lady presenting with intestinal obstruction, this should be considered as a possible diagnosis. This is especially so in the case of a virgin abdomen in this population – thereby raising suspicion of a cause other than adhesions.

Obturator hernia complications

The complications from an obturator hernia follow any other hernia, including strangulation (leading to bowel resection and associated complications), damage to the obturator nerve due to compressive symptoms, along with associated operative complications.

Obturator hernia diagnosis

Earlier diagnosis is challenging when the symptoms and signs are nonspecific. It is important to note that the physical signs of an obturator hernia are operator dependent and may not be immediately evident. Various imaging examinations such as ultrasonography, herniography, CT scan, and laparoscopy, have been used to establish the diagnosis. Abdominal X-ray and abdominal ultrasonography usually reveal a pattern of intestinal obstruction. Although ultrasonography is a fast, non-invasive, cost-effective, and easily-accessible diagnostic method, it still may be difficult to make the diagnosis of an obturator hernia. Kulkarniet al 21 reported that, the best imaging tool is CT scan with superior sensitivity and precision compared to other non-invasive diagnostic tools. CT is minimally invasive, easily accessible and can be performed over a short time. The most common CT scan finding in obturator hernia is herniation of small bowel extending through the obturator foramen which is located between the pectineus and obturator externus muscles 18. CT also distinguishes obturator hernia from other abdominal pathologies such as masses, tumors, hematomas, and abscesses 21. It has been reported that the use of CT before surgery in patients with an obturator hernia reduces intestinal resection rates and mortality 22. Nasir et al. 17 reported that preoperative CT is beneficial in the definitive and early diagnosis of obturator hernia but has no effect on the postoperative survival rate and does not increase long-term survival. Due to delayed presentation, advanced age, and the presence of comorbidities, there is often a delay in the diagnosis and surgical intervention in patients with an obturator hernia 10. Delay in the diagnosis may occur in these elderly patients due to their comorbidities and senescence with increased dementia 10.

Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio can be a good predictor of the severity of inflammatory response 23. High neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio levels can be used as a marker to estimate intestinal necrosis and the need for intestinal resection in patients who will undergo surgery for obturator hernia 24. Lactate levels, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio were higher in patients requiring a bowel resection due to non-viable bowel compared to the no-bowel resection group similar to the findings of Köksal et al 23.

Lactate is a product of anaerobic metabolism of glucose, and lactate concentration in arterial blood is an important marker in demonstrating tissue hypoperfusion 25. Anaerobic metabolism causes increased lactate levels, which is predictive for non-viable bowel 25. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio, lactate levels were higher in patients with strangulated bowel than in the incarceration group. Tanaka et al 26 reported that arterial blood lactate level (2.0 mmol/L or greater) is a determinative factor for non-viable bowel. The mean lactate level of six patients which had a small bowel strangulation was 7.73 mmol/L (5.4 – 9.4mmol/L) higher than the four patients with incarceration of small bowel with the range of 2.4 mmol/L (1.4 – 3.4mmol/L).

Obturator hernia treatment

The mean time from the beginning of symptoms to presentation was 4.4 days and ranged from 2 – 6 days in a study. The patients with non-viable bowelpresented after a mean of 5.66 days (5 – 6 days), which was higher than patients with viable bowel, 2.5 days (2 -3 days). Chang et al 27 reported that one of the major causes of bowel resection in these patients was the duration of symptoms.

Invariably, treatment is required of obturator hernias due to the likelihood of there being strangulation of the hernia. Also, these hernias often require treatment as an emergency procedure, as it is unlikely that the obturator hernia is likely to be reducible.

The treatment options for an obturator hernia are thus to be decided between an open and laparoscopic procedure. Laparoscopic hernia repairs are becoming more prevalent, with a number of reports of obturator hernia being repaired via a minimally-invasive approach 28. Given the location of obturator hernia deep within the pelvis, a laparoscopic approach allows for clear visualisation of the contents of the hernia and subsequent treatment. Almost all case reports published have described a transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) approach 29. This would allow the surgeon to visually inspect the contents of the hernia, and if bowel were present, to assess the viability of the incacerated/strangulated bowel. If a bowel resection were required, this could be performed either laparoscopically or via conversion to an open operation, depending on the experience of the operating surgeon.

The operative steps in an open procedure remain the same for any strangulated hernia repair – requiring a lower midline laparotomy, identification of the hernia, inspection of the contents, with possible bowel resection and anastomosis, followed by repair of the hernial orifice with either primary suture repair or with mesh placement 30. Other approaches are described, including retropubic and inguinal approaches; however, these should be performed by surgeons with experience in such approaches 29. A lower midline laparotomy being a very common approach may be one that surgeons would be more familiar with, and less likely to cause any issues.

The laparoscopic approach has been described previously. For a transabdominal preperitoneal repair, pneumoperitoneum is achieved (normally via an open Hassen technique), with ports placed 5cm either side of the midline below the umbilicus. This is especially so as it would be prudent for the clinical evaluation of the contralateral side (if initially diagnosed with a unilateral obturator hernia), as there might be missed bilateral herniae in this population 31. Once the hernial sac is identified, it is gently retracted using careful dissection if required. The hernial contents are visualized, paying attention to the bowel if present. A bowel resection may be required and will follow well-established operative steps. The excess hernial sac may be left behind, avoiding unnecessary dissection. The final part of the procedure would be the placement of a mesh. An incision is made on the anterior aspect of the abdomen using diathermy. This incision is then extended using sharp dissection, thus allowing the surgeon to tease the peritoneum alone away from the pre-peritoneal fat. Once adequate space is created, a mesh may be placed in this space. The peritoneal covering is then sutured closed.

Obturator hernia prognosis

Obturator herniae pose an interesting challenge in estimating mortality – due to their rare presentation. Historically, the mortality has been estimated between 13% to 40% and has been reported in more recent reports as well 32. Equally, the morbidity of the condition relates to the late presentation and identification of the problem. This can lead to infective complications (such as the development of collections) and anastomotic leaks (due to bowel resections) 33.

References- Mahendran B, Lopez PP. Hernia, Obturator. [Updated 2020 Apr 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554529

- Dhital B, Gul-E-Noor F, Downing KT, Hirsch S, Boutis GS. Pregnancy-Induced Dynamical and Structural Changes of Reproductive Tract Collagen. Biophys. J. 2016 Jul 12;111(1):57-68.

- Mantoo SK, Mak K, Tan TJ. Obturator hernia: diagnosis and treatment in the modern era. Singapore Med J. 2009 Sep;50(9):866-70.

- Mnari W, Hmida B, Maatouk M, Zrig A, Golli M. Strangulated obturator hernia: a case report with literature review. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;32:144.

- Petrie A, Tubbs RS, Matusz P, et al. Obturator Hernia: Anatomy,Embryology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clinical Anatomy. 2011;24:562–569.

- Skandalakis LJ, Skandalakis PN, Gray SW (1995) Obturator hernia. In: Nyhus LM, Condon RE et al (eds) Hernia. JB Lippincott Co, Philadelphia, pp 425–439

- Salimoglu, Semra & Demirli Atici, Semra. (2020). Prognostic Factors in Obturator Hernia. 10.22514/sv.2020.16.0038

- Thanapaisan C, Thanapaisal C. Sixty-One Cases of Obturator Herniain Chiangrai Regional Hospital: Retrospective Study. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89:2081-2085.

- Igari K, Ochiai T, Aihara A, et al. Clinical presentation of obturator hernia and review of the literature. Hernia. 2010;14:409–413.

- Şenol K, Bayam ME, Duman U, et al. Challenging management ofobturator hernia: a report of three cases and literature review. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2016;22:297–300.

- Gilbert JD, Byard RW. Obturator hernia and the elderly. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2019 Sep;15(3):491-493.

- Wu JM, Lin HF, Chen KH, Tseng LM, Huang SH. Laparoscopic preperitoneal mesh repair of incarcerated obturator hernia and contralateral direct inguinal hernia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2006 Dec;16(6):616-9.

- Losanoff JE, Richman BW, Jones JW. Obturator hernia. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2002 May;194(5):657-63.

- Petrie A, Tubbs RS, Matusz P, et al. Obturator Hernia: Anatomy, Embryology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clinical Anatomy.2011;24:562–569.

- Skandalakis LJ, Skandalakis PN, Gray SW, et al. Obturator hernia. Hernia.1995;4:425-439.

- Mantoo SK, Mak K, Tan TJ. Obturator hernia: diagnosis and treatment in the modern era. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:866-870.

- Nasir BS, Zendejas B, Ali SM, et al. Obturator hernia: the Mayo Clinic experience. Hernia. 2012;16:315-319.

- Igari K, Ochiai T, Aihara A, et al. Clinical presentation of obturatorhernia and review of the literature. Hernia. 2010;14:409–413.

- Naude G, Bongard F. Obturator hernia is an unsuspected diagnosis. Am J Surg. 1997;174(1):72-75. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(97)00024-X https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9610(97)00024-X

- Ziegler DW, Rhoads JE. Obturator hernia needs a laparotomy, not a diagnosis. Am. J. Surg. 1995 Jul;170(1):67-8.

- Kulkarni SR, Punamiya AR, Naniwadekar RG, et al. Obturator hernia: A diagnostic challenge.Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:606–608.

- Kammori M, Mafune K, Hirashima T, et al. Forty-three cases of obturator hernia. Am J Surg. 2004;187:549-552.

- Köksal H, Ateş D, Nazik EE, et al. Predictive value of preoperativeneutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio while detecting bowel resection inhernia with iestinal incarceration. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg.2018;24:207-210.

- Xie X, Feng S, Tang Z, et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Predicts the Severity of Incarcerated Groin Hernia. Med Sci Monit.2017;23:5558-5563.

- Karadeniz E, Bayramoğlu A, Atamanalp SS. Sensitivity andSpecificity of the Platelet-Lymphocyte Ratio and the Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio in Diagnosing Acute Mesenteric Ischemia inPatients Operated on for the Diagnosis of Mesenteric Ischemia: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. J Invest Surg. 2019;19:1-8.

- Tanaka K, Hanyu N, Iida T, et al. Lactate levels in the detection of preoperative bowel strangulation. Am Surg. 2012;78:86-88.

- Chang SS, Shan YS, Lin YJ, et al. A review of obturator hernia and a proposed algorithm for its diagnosis and treatment. World J Surg. 2005;29:450-454.

- Liu J, Zhu Y, Shen Y, Liu S, Wang M, Zhao X, Nie Y, Chen J. The feasibility of laparoscopic management of incarcerated obturator hernia. Surg Endosc. 2017 Feb;31(2):656-660.

- Amiki M, Goto M, Tomizawa Y, Sugiyama A, Sakon R, Inoue T, Ito S, Oneyama M, Shimojima R, Hara Y, Narita K, Tachimori Y, Sekikawa K. Laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal hernioplasty for recurrent obturator hernia: A case report. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2020 Jul;13(3):457-460.

- Sze Li S, Kenneth Kher Ti V. Two different surgical approaches for strangulated obturator hernias. Malays J Med Sci. 2012 Jan;19(1):69-72.

- Nakayama T, Kobayashi S, Shiraishi K, Nishiumi T, Mori S, Isobe K, Furuta Y. Diagnosis and treatment of obturator hernia. Keio J Med. 2002 Sep;51(3):129-32.

- Yokoyama Y, Yamaguchi A, Isogai M, Hori A, Kaneoka Y. Thirty-six cases of obturator hernia: does computed tomography contribute to postoperative outcome? World J Surg. 1999 Feb;23(2):214-6; discussion 217.

- Yip AW, AhChong AK, Lam KH. Obturator hernia: a continuing diagnostic challenge. Surgery. 1993 Mar;113(3):266-9.