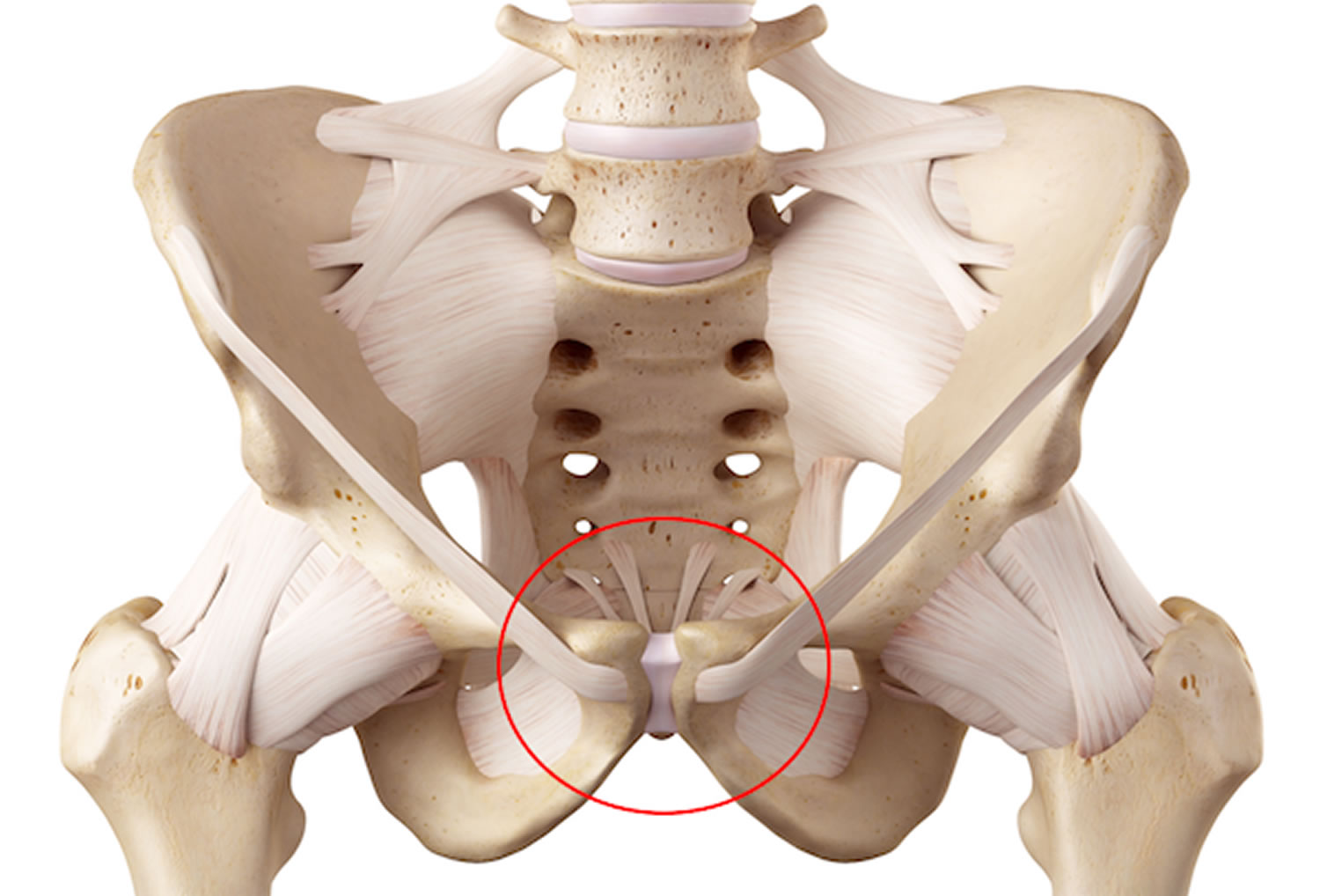

Osteitis pubis

Osteitis pubis is a noninfectious inflammatory condition of the pubic symphysis and surrounding muscle insertions 1. First described in patients who underwent suprapubic surgery or urologic procedures 2, however any pelvic surgery has the potential to cause osteitis pubis. Osteitis pubis is an uncommon cause of lower abdominal and suprapubic pain. Given its rarity, the diagnosis and management of osteitis pubis is challenging, as many urologists are unfamiliar with the condition and may ascribe the constellation of symptoms as expected side effects from a recent surgical procedure.

In the general surgery literature, herniorrhaphy has been linked with osteitis pubis 3 and in the field of obstetrics and gynecology, pregnancy has been associated in both the ante- and postpartum periods 4. In the urologic literature, it has been described after a myriad of procedures, including transurethral resection of the prostate, prostate cryotherapy, photovaporization of the prostate, periurethral collagen injection, transrectal needle biopsy of the prostate, high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment of the prostate, prostatectomy, and cystectomy 5. Classically, in the urologic literature, the procedures most frequently cited as risk factors are the traditional techniques for stress urinary incontinence, most commonly the Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz (MMK) urethropexy. The MMK procedure involves placing sutures directly into the pelvic bone periosteum of the pubic rami. Reviews of the MMK procedure have cited rates of osteitis pubis in up to 2.5% of patients, with a range of 0.7% to 2.5% 6. Although no large studies have been performed to better determine this rate in surgical patients, on average, in the urologic literature, osteitis pubis occurs in slightly fewer than 1 in 100 patients undergoing urologic procedures 1.

Although osteitis pubis can affect all age groups, it is rarely encountered in the pediatric population. Osteitis pubis occurs most commonly in men aged 30-50 years. Women are more frequently affected in their mid-30s 7.

The literature suggests that osteitis pubis is more prevalent in men. However, as women continue to lead more active lifestyles and become more involved in sports such as soccer, the relative sex-related incidences may change.

Osteitis pubis key points

- Osteitis pubis is a noninfectious inflammatory condition affecting the pubic symphysis. It is an uncommon cause of lower abdominal and suprapubic pain, but it can cause significant morbidity in patients affected, and often requires a lengthy recovery period.

- Pain is typically localized to the lower abdomen and groin, with radiation to the inner thigh adductor muscles, and often is associated with gait disturbances. Discomfort is usually aggravated by any activity that increases pressure on the pelvic girdle, including walking, coughing, sneezing, lying on one side, and walking up or down stairs.

- For all patients presenting with possible osteitis pubis, a thorough history and physical examination should be performed, with focus on any recent or remote urologic or pelvic surgical procedures, or any local trauma or repetitive injury to the area in question.

- Osteitis pubis is typically a clinical or radiographic diagnosis. Imaging modalities include conventional radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging, scintigraphy, and symphysography.

- Conservative treatment includes rest, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and physical therapy; invasive surgical techniques can be used if conservative measures fail.

Osteitis pubis causes

Several theories have been proposed as causes for the development of osteitis pubis, such as trauma, low-grade infection, and venous congestion. Despite these notions, at present, there is currently an incomplete understanding of the true cause of osteitis pubis; the cause may be multifactorial. Osteitis pubis may be caused by repetitive microtrauma or abnormal shearing forces to the pubic symphysis, which can itself be caused by muscle imbalance, poor flexibility, and sacroiliac (SI) joint dysfunction 7. These abnormalities of pelvic biomechanics—coupled with multiple repetitions of aggravating motions—cause microtrauma to the pubic symphysis, which results in inflammation and muscle spasm. Sacroiliac (SI) joint motion has a very large impact on the motion about the pubic symphysis. Batt et al 8 postulated that osteitis pubis is a result of muscle injury to the hip adductors or abdominal musculature, causing muscle spasm, which, in turn, produces increased shearing forces across the pubic symphysis.

Multiple sports-related occurrences of osteitis pubis have been reported. For instance, in a study of 502 Australian Football League (AFL) players, 161 of whom had sustained a hip or groin injury during their career with the league, Gabbe et al 9 found that players who had had such an groin injury during their time in elite junior football had a nearly 4 times greater chance of missing games because of osteitis pubis than other players did (as well as a 9.59 times greater chance of missing games because of a hip chondral or labral lesion).

Conditions associated with osteitis pubis include the following:

- Pregnancy and childbirth

- Gynecologic surgery

- Urologic surgery

- Athletic activities (eg, running, football, soccer, ice hockey, and tennis) 10

- Major trauma

- Repeated minor trauma

- Rheumatologic disorders

In the case of the athlete with a fever and osteomyelitis, Staphylococcus aureus is the most commonly cultured pathogen. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli have also been reported.

Osteitis pubis prevention

Flexibility in athletes is the most important step toward prevention of osteitis pubis. Proper body mechanics must be stressed in athletes who participate in activities that yield a higher incidence of this condition. SI dysfunction in running and skating must be aggressively treated so that the pubic symphysis does not become the victim of poor pelvic mechanics. In addition, early recognition of symptoms can prevent chronic and more severe symptoms.

Osteitis pubis symptoms

Presentation of patients with osteitis pubis can be broad and vague. The presenting symptoms of osteitis pubis can be almost any complaint about the groin or lower abdomen. Common complaints include the following:

- Pain localized over the symphysis and radiating outward

- Adductor pain or lower abdominal pain that then localizes to the pubic area (often unilaterally)

- Pain exacerbated by activities such as running, pivoting on 1 leg, kicking, or pushing off to change direction, as well as by lying on the side

- Pain occurring with walking, climbing stairs, coughing, or sneezing. The pain itself can be sharp during those activities, but commonly is described as an aching, throbbing, dull pain on cessation of the activity.

- A sensation of clicking or popping upon rising from a seated position, turning over in bed, or walking on uneven ground

- Weakness and difficulty ambulating

- Fever, chills, or rigors along with pubic pain (osteomyelitis must be ruled out)

The classic gait disturbance described in osteitis pubis is a “waddling” gait, a form of an antalgic gait. Given that the proximal thigh adductor muscle attachments are to the inferior pubic ramus just lateral to the pubic symphysis, it is not surprising that the aforementioned gait disturbances may develop.

On average, symptoms of osteitis pubis appear approximately 6 to 8 weeks after an offending surgical procedure, but the interval can be shorter or longer 11.

Physical findings for osteitis pubis can vary greatly 12. Such findings may include the following:

- Tenderness to palpation in the area over the superior pubic ramus

- When sacral innominate dysfunction is a cause, pain over one or both sacroiliac (SI) joints, often in conjunction with piriformis spasm and resultant sciatic-type pain

- With discrepancies of leg length (anatomic or functional), hip pain in the longer limb

The most specific test for osteitis pubis is a direct-pressure spring test, performed as follows:

- Palpate the athlete’s pubic bone directly over the pubic symphysis; tenderness to touch is often noted at that point

- Slide your fingertips a few centimeters laterally to each side, and apply direct pressure on the pubic rami; with this pressure, the patient feels pain in the symphysis

- To see if one side or the other produces more pain or lateral pain, apply ipsilateral pressure

The examination may also include the following as appropriate:

- Checking for inguinal hernia

- Assessment of muscle weakness, especially in hip adductors or flexors

- Gait assessment

- Gynecologic examination, if other symptoms suggest possible pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

- Rectal examination, if symptoms suggest possible prostatitis

Table 1. Physical examination tests and positive findings suggestive of osteitis pubis

| Test Name | Technique | Positive Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Pubic spring test | Examiner places simultaneous downward pressure on pubic rami with hands | Pain is reproduced at the pubic symphysisa |

| Lateral compression test | Patient is in lateral decubitus position | Pain is reproduced at |

| Examiner places downward pressure on the superior iliac wing | the pubic symphysis | |

| FABER (flexion, abduction, | Patient is supine | Pain is reproduced at |

| and external rotation) | Leg is flexed and the thigh abducted and externally rotated simultaneously (maneuver is performed 1 leg at a time) | the pubic symphysis |

| Adductor squeeze test | Patient is supine | Pain is reproduced at |

| Examiner places a fist between patient’s knees, and patient is asked to compress the examiner’s fist | the pubic symphysis |

Footnote: a) The test can also be performed on either side of pubic rami to see if pain lateralizes.

[Source 1 ]Osteitis pubis complications

Complications of osteitis pubis are minimal and few are reported. The major complication is a muscle-tendon injury of the adductor muscles due to muscle tightness. This complication is often prevented with correction of the biomechanical errors that caused the condition and flexibility training. A major complication of a misdiagnosed osteomyelitis is erosion of bone, which may take a very long time to remodel. Femoral artery involvement may occur but is rare.

Osteitis pubis diagnosis

Osteitis pubis is typically a clinical or radiographic diagnosis. Laboratory analysis is not required in most cases. In the setting of a febrile and sick-appearing patient, blood cultures and a complete blood count should be obtained, and consideration for inpatient admission should be given until stabilization has been demonstrated. If blood culture results are negative, aspiration and culture of the joint space may be beneficial to isolate any organisms. Because of the suggested association with positive urine culture and the higher rate of bacteriuria and urinary tract infection, a clean-catch urine culture can also be obtained. In some cases, erythrocyte sedimentation rate may also be elevated, though it is a nonspecific finding.

Laboratory studies are not required to make the diagnosis, but some may be helpful in eliminating other causes, including the following:

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- Urinalysis

- If the patient is febrile, a blood culture

Imaging studies that may be helpful include the following:

- Plain radiography

- Bone scanning (technetium-99m)

- Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Computed tomography (CT)

Other studies that may be considered are as follows:

- Aspiration of the pubic symphysis for culture, when the patient is febrile but blood cultures are negative

- Herniography, when a sports hernia is a strong consideration

Osteitis pubis treatment

Treatment modalities range from conservative management with rest to invasive surgical interventions. Due to the rarity of osteitis pubis, no prospective randomized controlled trials have been performed to determine the best treatment approach.

Rest and time are the primary treatment method for osteo pubitis. Rest is advised. Any activity or exercise that may place stress on the pelvic ring should be avoided. Athletes are advised to refrain from sporting activities for 3-6 months and then to return on a gradual supervised basis.

Physical therapy may be useful during the early stage and has the following goals:

- To help alleviate pain

- To start correcting the mechanical problems that precipitated the injury

Elements of therapy may include the following:

- Heat or ice may provide symptomatic relief

- Progressive ambulation with the aid of an assistive device and possible orthoses

- Avoidance of any exercise that may place stress on the pelvic ring

- Dynamic stabilization techniques

- Manipulation

- Ultrasound and electrical stimulation

Once the patient is free of pain, strengthening therapy can begin. Further PT measures may include the following:

- Exercises for the hip flexors, hip adductors, lumbar stabilizers, and abdominal muscles

- Hamstring and quadriceps exercises

- Stretching (daily or more often)

- Aquatic conditioning (except frog kicking)

- Stair-stepping machines (as tolerated)

- Sports-specific activities, with offending motions added last

- Manipulation

Pharmacologic therapy may include the following:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Steroids (oral or injected)

- Prolotherapy with dextrose and lidocaine

Surgery is rarely warranted for osteitis pubis and is generally reserved for failure of conservative management. Surgical approaches, if indicated, include the following:

- Curettage

- Arthroscopic curettage combined with adductor debridement and reattachment

- Arthrodesis

- Wedge resection of public symphysis

- Wide resection of public symphysis

Osteitis pubis prognosis

With definitive diagnosis and treatment, the prognosis for osteitis pubis is excellent. Although rare instances of mortality from femoral artery involvement have been reported in the obstetric literature, morbidity is more commonly observed secondary to pain and difficulty with ambulation.

In most cases, osteitis pubis resolves with rest. The average time to full recovery is 9.5 months in men and 7.0 months in women. Some reports suggest that recovery may take up to 32 months. Recurrence is more common in males. More aggressive therapy is often needed when an athlete refuses to modify activities or rest 13. With aggressive physical therapy and judicious use of medications, the athlete often returns to the previous level of activity.

References- Gomella P, Mufarrij P. Osteitis pubis: A rare cause of suprapubic pain. Rev Urol. 2017;19(3):156–163. doi:10.3909/riu0767 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5737342

- Beer E. Periostitis of the symphysis and descending rami of the pubes following suprapubic operations. Int J Med Surg. 1924;37:224–225.

- Osteitis pubis: an unusual complication of herniorrhaphy. Harth M, Bourne RB. Can J Surg. 1981 Jul; 24(4):407-9.

- Osteitis pubis: an unusual postpartum presentation. Usta JA, Usta IM, Major S. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003 Nov; 269(1):77-8.

- Symphysitis following transrectal biopsy of the prostate. Adam C, Graser A, Koch W, Trottmann M, Rohrmann K, Zaak D, Stief C. Int J Urol. 2006 Jun; 13(6):832-3.

- Osteitis pubis after Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz urethropexy. Garcia-Porrua C, Picallo JA, Gonzalez-Gay MA. Joint Bone Spine. 2003 Feb; 70(1):61-3.

- Osteitis pubis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/87420-overview

- Batt ME, McShane JM, Dillingham MF. Osteitis pubis in collegiate football players. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995 May. 27(5):629-33.

- Gabbe BJ, Bailey M, Cook JL, Makdissi M, Scase E, Ames N, et al. The association between hip and groin injuries in the elite junior football years and injuries sustained during elite senior competition. Br J Sports Med. 2010 Sep. 44(11):799-802.

- Garvey JF, Read JW, Turner A. Sportsman hernia: what can we do?. Hernia. 2010 Feb. 14(1):17-25.

- Osteitis pubis: observations based on a study of 45 patients. COVENTRY MB, MITCHELL WC. JAMA. 1961 Dec 2; 178():898-905.

- Ruane JJ, Rossi TA. When groin pain is more than “just a strain”: navigating a broad differential. Phys Sportsmed. 1998. 26(4):78-103.

- Holt MA, Keene JS, Graf BK, Helwig DC. Treatment of osteitis pubis in athletes. Results of corticosteroid injections. Am J Sports Med. 1995 Sep-Oct. 23(5):601-6.