Medial plica

Medial synovial plicae are embryological structures that form within the knee 1. The medial plica of the knee (referred to by some as the Aoki ledge or Iino band) is a thin, well-vascularized intraarticular fold of the knee joint lining or synovial tissue, over the medial aspect of the knee (Figure 1). The medial plica is a normal anatomical structure found within the joint capsule of the knee and is present in everyone, but is more prominent in some people. It has been noted to be present as a shelf of tissue over the medial aspect of the knee at the time of arthroscopic surgery in up to 95% of patients 2. Proximally, it is attached to the genu articularis muscle, while distally it courses over the far medial aspect of the medial femoral condyle to attach to the distomedial aspect of the intraarticular synovial lining of the knee 3. At this location, it basically blends into the medial patellotibial ligament on the medial aspect of the retropatellar fat pad 4. The medial plica is composed of relatively elastic tissues which asymptomatically conform to the changes in shape and lengths of the plica folds as the knee flexes and extends 5. Impingement of the plicae during motion of the knee can cause inflammation, resulting in medial knee pain. In some patients, particularly those who may have had injuries or multiple surgeries over the medial aspect of the knee, the medial synovial plica may become very thick and fibrotic and may catch over the medial aspect of the medial femoral condyle 6. The medial suprapatellar plica of the knee is an intra-articular synovial fold on the medial aspect of the knee. This plica is one of the most common sources of knee pain in patients; however, a proper rehabilitation program allows most patients to recover from the symptoms associated with irritation of this structure 7.

In all patients, the medial synovial plica will glide over the anteromedial aspect of the medial femoral condyle with flexion and extension of the knee. In most patients, this gliding motion of the plica will occur without any symptoms, because of the high viscosity of the native synovial fluid of the knee. However, in patients with effusions, which decreases the viscosity of their synovial fluid, patients may either have crepitation or a catching of their medial synovial plica with flexion and extension of the knee. This crepitation or catching can occur with patients while going up or down stairs, squatting and bending, and other types of activities.

Since the medial synovial plica does have an attachment to the genu articularis muscle, and also an indirect attachment to the quadriceps musculature due to its attachment to the joint lining, it is dynamically controlled by the quadriceps muscles 8. Thus, medial plica irritation is more common in patients who have poor quadriceps tone or other problems with joint muscle balance around the knee.

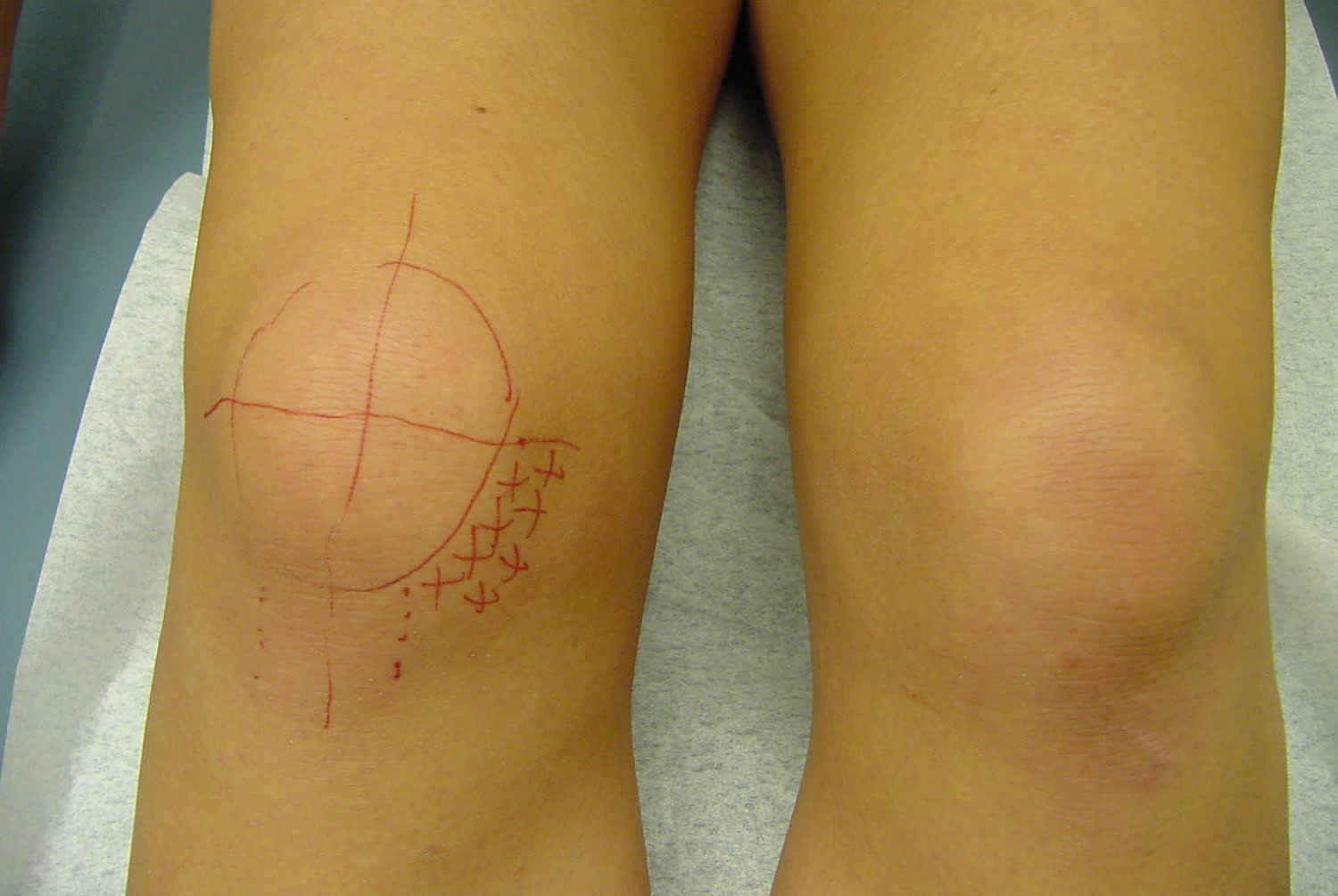

Figure 2. Medial synovial plica palpation (Plica snap test)

[Source 3 ]Figure 3. Medial plica syndrome

Footnote: The inferomedial quadrant is usually the most painful region by physical examination. This area is highlighted by several X’s in this figure. A painful taut band of tissue that emanates from the central portion of the medial patella may often be palpated (3 o’clock position on the figure).

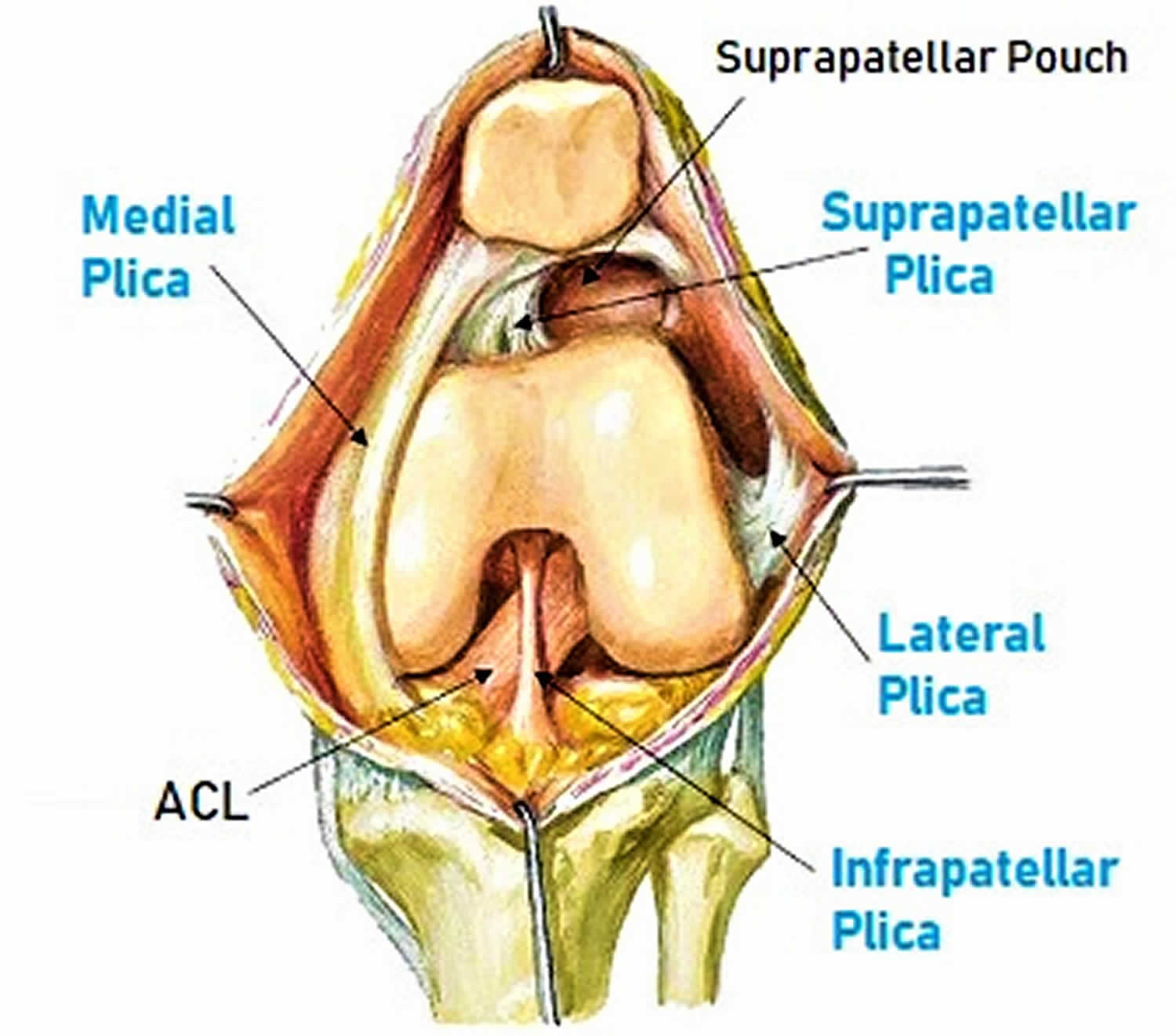

Medial plica anatomy

During embryonic development, the knee is divided initially by synovial membranes into three separate compartments 9. By the third or fourth month of fetal life, the membranes are resorbed, and the knee becomes a single chamber. If the membranes resorb incompletely, various degrees of septation may persist. These embryonic remnants are known as synovial plicae. Four types of synovial plicae of the knee have been described in the literature 10.

The suprapatellar plica (plica synovialis suprapatellaris) divides the suprapatellar pouch from the remainder of the knee. Rarely, it may initiate a suprapatellar bursitis or perhaps chondromalacia, and symptoms secondary to these conditions may be present 11. Anatomically, suprapatellar plica can be complete or in the form of a porta, which only partially separates the compartments. It courses from the anterior femoral metaphysis or the posterior quadriceps tendon to the medial wall of the joint. It usually begins proximal to the superior pole of the patella but may begin anywhere.

The mediopatellar plica or medial plica (referred to by some as the Aoki ledge or Iino band) is the most frequently cited cause of plica syndrome. It lies on the medial wall of the joint, coursing from a suprapatellar origin obliquely down to insert on the infrapatellar (ie, Hoffa) fat pad. The mediopatellar plica, sometimes known as a shelf, lies in the coronal plane 12.

The rare and poorly documented lateral synovial plica is a wider and thicker band than the medial plica. It is located along the lateral parapatellar synovium, inserting on the lateral patellar facet and extending distally toward the infrapatellar region. It has been argued that the lateral plica, rather than being a vestigial septum, is derived from the parapatellar adipose synovial fringe.

The plica that is the least symptomatic of all, the infrapatellar plica (ligamentum mucosum) is, ironically, the one most commonly encountered. Some authors even claim that the infrapatellar plica is never responsible for plica syndrome. This bell-shaped remnant originates in the intercondylar notch, widens as it sweeps through the anterior joint space, and attaches to the infrapatellar fat pad. This plica’s ability to obscure portal entry sites or interfere with visualization during arthroscopy is touted as its only significance.

Kim et al classified infrapatellar plica (ie, ligamentum mucosum) into the following five groups 13:

- Separate type – 60.5%

- Split type – 13.5%

- Vertical septum type – 10.5%

- Fenestra type – 1.0%

- None present – 14.5%

In a clinical study of 400 knees in more than 350 patients, Kim and Choe 14 found suprapatellar plicae in 87%, mediopatellar plicae in 72%, infrapatellar plicae in 86%, and lateral plicae in 1.3%.

Medial plica syndrome

Medial plica syndrome also called medial plica irritation of the knee is a constellation of signs and symptoms that occur secondary to injury or overuse. Medial synovial plicae are normal structures found in many knees. Under normal circumstances, these plicae are not associated with any painful conditions. However, with the right combination of events they can become quite painful 15. These events almost certainly include a somewhat exuberant plical shelf at baseline combined with an inciting event (either discrete macrotrauma or repeated microtrauma). Once an inflammatory process is established, the normal plical tissue may hypertrophy into a truly pathologic structure 16.

Medial plica syndrome causes

The cause of symptomatic medial plica is unclear. Potential causes of inflammation include repetitive stress, a single blunt trauma, loose bodies, osteochondritis dissecans, meniscal tears, or other aggravating knee pathology. The most common symptomatic plica is medial plica; occasionally, suprapatellar plica may also be symptomatic 17.

A popular theory for the initiation of inflammation is that the plica is converted to a bowstring, which causes it to contact the medial femoral condyle. During flexion of the knee, the plica causes an abrasion to the condyle, resulting in symptoms. Others contend that a plica need not contact the femoral condyle to cause symptoms.

One study found that the onset of symptoms was usually delayed until adolescence. Possible explanations include a decrease in tissue elasticity with age, and a biomechanical change resulting from a growth spurt.

Medial plica syndrome symptoms

The spectrum and diversity of symptoms can make plica syndrome difficult to pinpoint. Often, symptoms resemble or overlap with those of other pathologic conditions 18.

Reported symptoms include the following:

- Anterior or anteromedial knee pain

- Intermittent or episodic pain

- Clicking

- High-pitched snapping

- Occasional giving way

- Locking (really pseudolocking) and catching

- Aggravation of symptoms by activity, by stair climbing, or by prolonged standing, squatting, or sitting

Meniscal tears, patellar tendinitis, Osgood-Schlatter disease, Sinding-Larsen-Johansson disease, and patellar instability are the most commonly found concomitant conditions.

Medial plica syndrome diagnosis

One of the most important points in diagnosing medial synovial plica pathology is obtaining an appropriate history from the patient. Patients usually describe pain which is dull, achy, and increases with activity. When asked to point to the area of their pain, they will commonly point to the proximomedial aspect of the knee, proximal to the medial joint line. While some patients may note a history of trauma to this area of the knee, most patients do not have any specific history of trauma to their medial plica. Over half of patients have a history of participating in some type of strenuous activity which requires repetitive flexion and extension motion of the knee, which then irritates their patellofemoral joint.

Most patients will complain of an achy type pain over the medial aspect of their knee, which is aggravated by activity and can be particularly bothersome at night. Their complaints of night pain over this area of the knee are due to the effects of inflammation, which can be particularly bothersome with activities. Patients most commonly complain of pain with activities which stress their patellofemoral joints, such as ascending and descending stairs, squatting and bending, and arising from a chair after sitting for an extended period of time 1. In addition, they may note difficulty with sitting still for long periods of time without having to move and stretch their knees. They also may complain of a catch over the anteromedial aspect of their knee upon arising from a chair following prolonged periods of sitting. In some patients, plica catching may present as a pseudo-locking event to their knee when they have been sitting down for an extended period of time and they first arise. Some patients may describe these pseudo-locking events as instability or catching of their patella. Clicking, giving way, and pseudo-locking have been reported in approximately 50% of all patients who present with medial plica irritation 19. Patients who might have problems with activity-related effusions may also complain of pain over the anterior aspect of their knee. While these activity-related effusions may not be directly caused by medial plica pathology, and are more commonly due to underlying quadriceps mechanism weakness, meniscal tears, and/or osteoarthritis, but they can cause secondary medial plica irritation. In addition, patients who have had postoperative or post-injury weakness of their affected extremity may develop pain over the anteromedial aspect of their knee in the region of the medial synovial plica.

A definitive diagnosis of medial plica irritation is usually obtained by physical exam. A normal examination of the patellofemoral joint should always include an examination of the patient’s medial synovial plica fold to determine if they have any irritation of this structure.

In examining the medial synovial plica, it is important to make sure that the patient is relaxed, which is usually accomplished by having the patient lie supine on the examining table with both legs relaxed. The examiner then palpates for the medial synovial plica by rolling ones fingers over the plica fold which is located between the medial border of the patella and the adductor tubercle region of the medial femoral condyle (Figure 2). The medial synovial plica will present as a ribbon-like fold of tissue under ones finger which can be rolled directly against the underlying medial femoral condyle 20. While some patients may have a sensation of mild pain when palpating the medial synovial plica, it is important to ascertain while performing this test if this reproduces their symptoms. It is also very important to compare the sensation to the contralateral normal knee to see if there is a difference in the amount of pain produced. It has been well demonstrated that this portion of the medial joint line and synovium is well innervated and irritation of the medial plica can be quite painful in some patients 21.

As with any other physical diagnosis, it is important to concurrently ascertain if there are other areas of pathology for structures that are located close to the medial synovial plica to confirm one’s diagnosis. In acute injuries, one should make sure that there is no injury to the meniscofemoral portion of the superficial medial collateral ligament. In this instance, one would apply a valgus stress to the knee and palpate at the joint line for both any potential joint line opening to application of the valgus stress and also to see if there is any well localized pain or edema in the region of the meniscofemoral portion of the superficial medial collateral ligament. In addition, in acute injuries, one should make sure that there has not been a lateral patellar subluxation episode with injury to the medial patellofemoral ligament. The lateral patellar apprehension test, performed with the knee flexed to approximately 45° of knee flexion, can help to determine if there has been injury to the medial patellofemoral ligament by applying a lateral translation force to the patella when it is flexed to approximately 45° of knee flexion and assessing if this translation causes pain or an apprehensive feeling like the patella will dislocate. This pain should be different from pain produced when the plica is rolled under ones fingers. Further, one should make sure that the pain over the medial aspect of the knee is not directly due to localized or diffuse areas of chondromalacia of the patellofemoral joint. In this instance, one would roll the superior and inferior poles of the patella both proximally and distally, as well as medially and laterally, in the trochlear groove, to determine if there is any true retropatellar crepitation with translation of the patella in the trochlear groove. This evaluation is different from assessing for crepitation of the patellofemoral joint with active flexion and extension of the knee as many of these patients may have catching of their medial plica causing the crepitation with active flexion and extension of the knee rather than true patellofemoral chondromalacia causing this auditory occurrence. In addition, one should assess for hamstring tightness, which can cause stress to the anterior aspect of the knee, by assessing the hamstring-popliteal angle and by palpation of the main hamstring attachment sites of the knee (pes anserine bursa, semimembranosus bursa and biceps bursa.

When one is not sure about the diagnosis of medial synovial plica irritation and it is difficult to determine if the patient has a true intraarticular or an extraarticular pathology over this area of the knee, one can confirm the diagnosis with an intraarticular anesthetic injection of 1% Lidocaine In this instance, the injection should be intraarticular and one should not attempt to inject directly into the medial synovial plica. This distinction is important to differentiate because the plica is actually intraarticular. If one does have good pain relief with an intraarticular anesthetic injection, one can be sure that the pathology is intraarticular rather then extraarticular over this portion of the knee. Although one series of intraplical injections reported good results 22, it has also been reported, and we also concur, that injection directly into the thin plica band is very difficult to perform and reliable placement of the needle during the injection is impossible 19. It is generally not recommended to perform a diagnostic arthroscopy to verify that a patient has an isolated medial plica irritation, because the most successful treatments for medial plica irritation are non-operative and an arthroscopy can cause further irritation and scarring of the medial synovial plica.

It is recommended to obtain a standing AP, lateral, and 45° patellar sunrise (axial) radiographs of the knee to rule out other sources of pathology. While many patients who have an irritated medial synovial plica have normal radiographs, it is important to rule out that the patients do not have any underlying arthritis, areas of osteochondritis desiccans, osteophyte formation, fractures, or other bony pathology which could be contributing to the irritation of the medial synovial plica.

In addition, diagnosis of medial plica irritation on MRI scans is non-specific 23. The physical exam should be able to demonstrate any significant thickening and fibrosis of a medial synovial plica. MRI’s are more useful in determining if there are other pathologies contributing to medial synovial plica irritation rather than in directly diagnosing pathology in this portion of the knee.

Medial plica syndrome treatment

Physical therapy

The main treatment regimen for medial plica irritation is non-operative 3. For patients who have medial plica irritation as their main diagnosis without any underlying knee pathology contributing to their plica irritation, there is a very good chance that their symptoms will improve with a guided rehabilitation program 20. The most successful rehabilitation programs focus on strengthening the quadriceps muscles, which are directly attached to the medial plica, and avoiding activities which cause medial plica irritation 8. These exercises can include quadriceps sets, straight leg raises, leg presses, and mini-squats, as well as, a walking program, the use of a recumbent or stationary bicycle, a swimming program, or possibly an elliptical machine. Patients should work on gradually increasing strength over time to overcome any strength deficit in their quadriceps mechanism. Concurrent with this, patients should also work on a frequent hamstring stretching program throughout the day 23. Tight hamstrings can increase the force needed to extend the knee, which can be an important source of medial plica irritation. Thus, it is important to make sure that the hamstrings are stretched frequently to diminish this extra stress on the anterior part of the knee.

Most patients can utilize either a self-directed or a physical therapy guided exercise program for the first 6–8 weeks after they have been examined. In the majority of circumstances, this program will alleviate the patient’s symptoms and the patient can often follow-up with their physician on an as needed basis if symptoms persist after this rehabilitation program. In this therapy regimen, patients participate in quadriceps strengthening exercises including a walking program, the use of a recumbent or stationary bicycle, a swimming program, or utilizing an elliptical machine. It is especially important to make sure that patients avoid knee extension exercises, because open chain exercises can cause plica irritation and limit patient’s improvements with an exercise regimen.

Concurrent with a good quadriceps strengthening program, it is also important to make sure that patients work on a frequent hamstring stretching program. They should work on stretching their hamstrings several times a day and not just once daily. As mentioned previously, tight hamstrings place extra stress on the anterior aspect of the knee when the patient tries to extend their knee and this is a frequent cause of medial plica irritation. Thus, it is important to make sure that patients do stretch their hamstrings concurrently with strengthening their quadriceps to maximize the benefit from an exercise program.

In cases where patients are not getting better with a physical therapy program, or in those patients who have such an irritated plica that a therapy program may not be beneficial directly, consideration for an intraarticular corticosteroid injection is necessary. In candidates for an intraarticular steroid injection, we perform the injection to attempt to quiet down their knee symptoms such that they can participate in an exercise program to address their medial plica irritation. It is not sufficient solely to rely on the injection to quiet down ones knee because the underlying problem of a weak quadriceps mechanism and tight hamstring muscles may persist after the injection and result in a recurrence of the medial plica irritation after the beneficial effects of the injection wear off. Thus, it is very important to make sure that the patients do participate in an exercise program, even if they have complete relief of their symptoms, after an intraarticular steroid injection to treat medial plica irritation. It is usually necessary to have the patients refrain from exercising or placing any significant stress to their knee for the first 24–48 hours after their steroid injection because the knee may have more post-injection soreness. In addition, it is important to document with the patients whether or not they had good pain relief while the local anesthetic portion of the injection was working to verify that they do have an intraarticular knee cause of their knee pain.

It is rare that patients need arthroscopic surgery to treat isolated medial plica pathology, because the medial plica is a part of the joint lining and resection of it will result in the joint lining growing back. Since the body heals back this type of resection with scar, the tissue may heal back with painful scar and the patient may have more symptoms. Since the treatment of a painful plica after an arthroscopic resection can often cause patients to have more pain than they did prior to the arthroscopic resection, it is important to make sure that a patient has pathology of this area which is not responsive to an exercise program, and possibly injections, prior to consideration of resection of this tissue 24. It is important to recognize that surgery for an irritated plica is uncommon, and historically it comprised only 2–5% of all arthroscopic surgery at a time when magnetic resonance imaging scans were not commonly used and more surgeries were performed for diagnostic reasons 23. Griffith and LaPrade 3 have found that arthroscopic resections of irritated plicas are rarely performed today. The usual instances where one may have some benefit from resection of a medial synovial plica may be where the plica is acting as a shelf which is catching over the medial femoral condyle and causing some erosion of the articular cartilage in this area 25. In these circumstances, patients may have good pain relief and decreased catching sensations in their knee after an arthroscopic resection of their medial plica. In this instance, it is usually not recommended to divide the pathologic plica and resect it totally because the pathologic plica may grow back and the patient may have recurrence of their symptoms 23. It has also been noted that the results of arthroscopic plica excision are more successful in adolescents than in older patients 26.

Indirect treatment of the medial plica irritation may also be very beneficial to patients. In these instances, the pathology is deep within the knee. Treatment of localized areas of arthritis, meniscal tears, or other knee pathologies, may decrease the pain and swelling of the knee which resulted in secondary irritation of the medial plica. In these instances, it may be beneficial for the patient to undergo surgery to treat the secondary cause of plica irritation. In these circumstances, it is not recommended to resect the medial synovial plica, because there is a very good chance that it will get better with an exercise program after surgery and patients may not have pain relief of their plica irritation if it is resected arthroscopically.

Surgical intervention

In patients who have exhausted all other means of therapy, an arthroscopic evaluation of the knee may be indicated. Because a debrided synovial plica results in alleviation of symptoms in only about 60-70% of cases, with some of the remaining patients actually having more pain after surgery, it is recommended that the synovial plica be debrided only if significant scar tissue is present in the plica or if shelf erosion is noted on the medial femoral condyle from a fibrotic plica.

A study by Kan et al 27 on 44 patients arthroscopically diagnosed with medial plica syndrome found that since the length of time from injury to surgery directly influenced the severity of cartilage damage, in order to reduce the potential for cartilage damage, surgical treatment should be an option when pain does not cease or when the medial synovial plica ruptures or covers part of the anterior aspect of the medial femoral condyle.

Some practitioners advocate resection of asymptomatic medial plicae in patients with a coexisting knee pathology that requires surgical intervention 28. This is based on the idea that removing a medial plica helps to prevent future complications; however, this has been a source of debate in the orthopedic field.

Complications

Complications of surgical treatment of plica syndrome are really complications associated with arthroscopic surgery of the knee. These include septic arthritis, neurapraxias or neuromas, and synovial fistulae. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy may also occur after such surgery. The incidence of each of these complications is extremely low (<1% in most cases). Only patients with particular risk factors (eg, diabetes, steroid dependence, or history of reflex sympathetic dystrophy) may be at significantly higher risk.

Medial plica syndrome prognosis

The outcome of surgical treatment for well-selected patients with plica syndrome is very good 29. A clinical trial conducted by Johnson et al in England demonstrated a success rate higher than 80% 30. In this same study, nearly 50% of patients in the control group experienced continued symptoms severe enough that they later returned for definitive arthroscopic resection of their plicae.

In a predominantly adult population (average age, 25 years; range, 11-56 years), Kasim and Fulkerson 31 reported 88% moderate-to-substantial improvement at an average of more than 4 years after resection of localized segments of painful retinacula (ie, plicae) about the knee.

References- Medial Synovial Plica Irritation. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/89985-overview

- The synovial plicae in the knee joint. Gurbuz H, Calpur OU, Ozcan M, Kutoglu T, Mesut R. Saudi Med J. 2006 Dec; 27(12):1839-42.

- Griffith CJ, LaPrade RF. Medial plica irritation: diagnosis and treatment. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1(1):53–60. doi:10.1007/s12178-007-9006-z https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2684145

- Arthroscopic findings of the synovial plicae of the knee. Kim SJ, Choe WS. Arthroscopy. 1997 Feb; 13(1):33-41.

- Diagnosis and treatment of the plica syndrome of the knee. Hardaker WT, Whipple TL, Bassett FH 3rd. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980 Mar; 62(2):221-5.

- Arch type pathologic suprapatellar plica. Kim SJ, Shin SJ, Koo TY. Arthroscopy. 2001 May; 17(5):536-8.

- Bellary SS, Lynch G, Housman B, et al. Medial plica syndrome: A review of the literature. Clin Anat. 2012 Jan 3.

- Arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic synovial plica of the knee. Long-term followup. Dorchak JD, Barrack RL, Kneisl JS, Alexander AH. Am J Sports Med. 1991 Sep-Oct; 19(5):503-7.

- Plica syndrome. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1252011-overview#a12

- Kent M, Khanduja V. Synovial plicae around the knee. Knee. 2010 Mar. 17 (2):97-102.

- Pipkin G. Knee injuries: the role of the suprapatellar plica and suprapatellar bursa in simulating internal derangements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1971 Jan. 74:161-76.

- Mine T, Ihara K, Kawamura H, Seto T, Umehara K. Shelf syndrome of the knee in elderly people: a report of three cases. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2012 Aug. 20 (2):269-71.

- Kim SJ, Min BH, Kim HK. Arthroscopic anatomy of the infrapatellar plica. Arthroscopy. 1996 Oct. 12 (5):561-4.

- Kim SJ, Choe WS. Arthroscopic findings of the synovial plicae of the knee. Arthroscopy. 1997 Feb. 13 (1):33-41.

- Patel D. Plica as a cause of anterior knee pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 1986 Apr. 17 (2):273-7.

- Ewing JW. Plica: Pathologic or Not?. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993 Nov. 1 (2):117-121.

- O’Keeffe SA, Hogan BA, Eustace SJ, Kavanagh EC. Overuse injuries of the knee. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2009 Nov. 17 (4):725-39, vii.

- Lipton R, Roofeh J. The medial plica syndrome can mimic recurring acute haemarthroses. Haemophilia. 2008 Jul. 14 (4):862.

- Symptomatic synovial plicae of the knee. Johnson DP, Eastwood DM, Witherow PJ. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993 Oct; 75(10):1485-96.

- Acute Knee Injuries; On-the-Field and Sideline Evaluation. Laprade RF, Wentorf F. Phys Sportsmed. 1999 Oct; 27(10):55-61.

- Conscious neurosensory mapping of the internal structures of the human knee without intraarticular anesthesia. Dye SF, Vaupel GL, Dye CC. Am J Sports Med. 1998 Nov-Dec; 26(6):773-7.

- Medial synovial shelf plica syndrome. Treatment by intraplical steroid injection. Rovere GD, Adair DM. Am J Sports Med. 1985 Nov-Dec; 13(6):382-6.

- Plica: Pathologic or Not? Ewing JW. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993 Nov; 1(2):117-121.

- The plica syndrome: a new perspective. Broom MJ, Fulkerson JP. Orthop Clin North Am. 1986 Apr; 17(2):279-81.

- Lyu SR, Hsu CC. Medial plicae and degeneration of the medial femoral condyle. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(1):17–26.

- Johnson DP, Eastwood DM, Witherow PJ. Symptomatic synovial plicae of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75:1485–96.

- Kan H, Arai Y, Nakagawa S, Inoue H, Hara K, Minami G, et al. Characteristics of medial plica syndrome complicated with cartilage damage. Int Orthop. 2015 Dec. 39 (12):2489-94.

- Lyu SR, Chiang JK, Tseng CE. Medial plica in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a histomorphological study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010 Jun. 18(6):769-76.

- Kinnard P, Levesque RY. The plica syndrome. A syndrome of controversy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984 Mar. (183):141-3.

- Johnson DP, Eastwood DM, Witherow PJ. Symptomatic synovial plicae of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993 Oct. 75 (10):1485-96.

- Kasim N, Fulkerson JP. Resection of clinically localized segments of painful retinaculum in the treatment of selected patients with anterior knee pain. Am J Sports Med. 2000 Nov-Dec. 28 (6):811-4.