What is pannus

Pannus is an inflammatory soft tissue mass most frequently associated with rheumatoid arthritis and its associated chronic atlanto-axial subluxation 1. Pannus can also be seen in other conditions in which a chronic atlanto-axial instability exists, such as degenerative arthropathies, os odontoideum or posttraumatic pseudoarthrosis of the odontoid process 2. Therefore, many authors have concluded that chronic craniovertebral junction instability plays a very important role in the development of pannus 3.

Pannus is an edematous thickened hyperplastic synovium infiltrated by T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes, plasmocytes, macrophages and osteoclasts. Pannus will gradually erode bare areas initially, followed by the articular cartilage. Pannus causes a fibrous ankylosis which eventually ossifies 4. However, there is some controversy in the nature of this pannus. For some authors, this is an inflammatory granulation tissue, which grows from the sinovial between the dens and the posterior articular facet of the posterior arch of C1, or between the dens and the transversal ligament 5. For other authors, this tissue is a reactive fibrous tissue secondary to the mechanical stress more than secondary to an inflammatory process 6. This would be supported by the fact that pannus is found in patients with no systemic inflammatory process and with only chronic atlanto-axial instability, as happens in cases of traumatic pseudoarthrosis, os odontoideum or degenerative arthropathy 7.

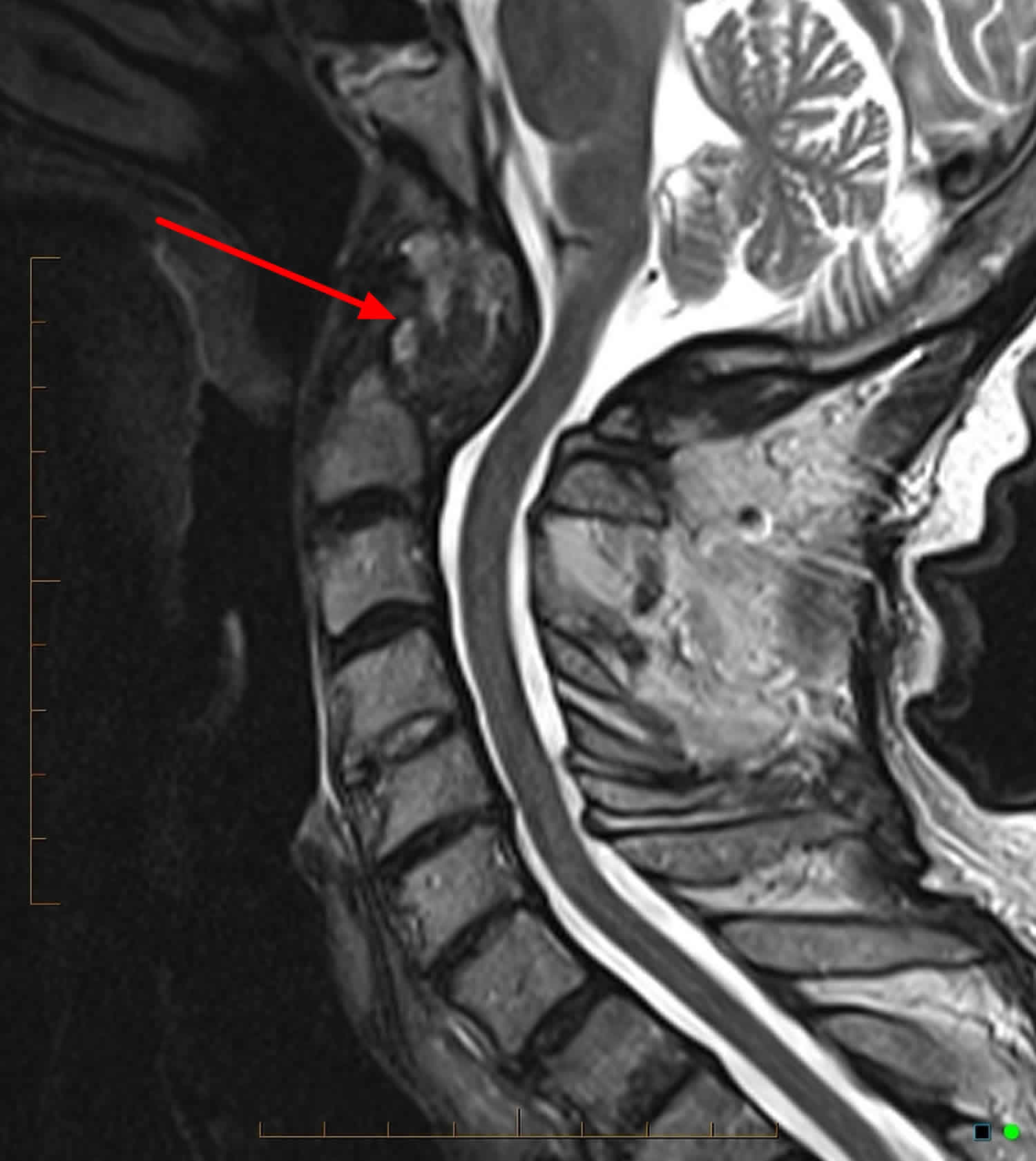

Figure 1. Pannus (MRI scan of cervical spine)

Footnote: 75 year old male patient with known rheumatoid arthritis. Now worsening of neck pain. Large soft tissue mass encircling the marked erosion of the dens consistent with “pannus”, is typical of advanced rheumatoid arthritis. Minor extrinsic compression to the upper cervical cord.

[Source 8 ]Pannus formation

Recent theories on the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis suggest that the synovial cells of these patients chronically express an antigen that triggers the production of rheumatoid factor (RF), an immunoglobulin molecule directed against other autologous immunoglobulins. An inflammatory response is initiated, involving immune complex formation, activation of the complement cascade, and infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The proliferating fibroblasts and inflammatory cells produce granulation tissue, known as rheumatoid pannus, within the synovium. The pannus produces proteolytic enzymes capable of destroying adjacent cartilage, ligaments, tendons, and bone. The destructive synovitis results in ligamentous laxity and bony erosion with resultant cervical instability and subluxation 9.

Atlantoaxial subluxation results from erosive synovitis in the atlantoaxial, atlanto-odontoid, and atlanto-occipital joints and the bursa between the odontoid and the transverse ligament (see Figure 1 below).

Involvement of the cervical spine typically begins early in the rheumatoid arthritis disease process and often parallels the extent of peripheral disease. Of the 3 types of involvement, atlantoaxial instability is the most common, occurring in up to 49% of patients 10. Whereas most of these subluxations are anterior, approximately 20% are lateral and approximately 7% are posterior. Superior migration of the odontoid is seen in up to 38% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Subaxial subluxation is seen as a discrete pathologic entity in 10-20% of patients.

Subaxial subluxation also develops after previous upper cervical fusions 11. In one series of 79 patients, 36% developed subaxial subluxation at an average of 2.6 years following occipitocervical fusion, and 5.5% experienced subaxial subluxation an average of 9 years following atlantoaxial fusion 12.

Pannus is located ventrally to the bulbomedullary junction, and can produce a severe myelopathy and even sudden death. Transoral approach has been proposed as the best way to directly manage the ventral compression caused by pannus 13. However, several case reports have been reported in the last years in which pannus resolution has been documented after posterior stabilization in different pathologies, such as rheumatoid arthritis, degenerative arthropathies, os odontoideum and traumatic pseudoarthrosis 1.

Rheumatoid pannus symptoms

Rheumatoid involvement of the cervical spine (rheumatoid spondylitis, ankylosing spondylitis) is just one element in a systemic disease process. Cervical involvement often correlates with the degree of hand and wrist erosion. Cervical involvement also has been associated with the presence of rheumatoid nodules and the use of corticosteroids. Classically, craniocervical neck pain often is associated with occipital headaches.

Intractable neck pain radiating superiorly towards the occiput is one of the earliest and most common symptoms of atlantoaxial subluxation (70% of patients) 14. Neck pain can also be a symptom of active ankylosing spondylitis and thereby difficult to distinguish from atlantoaxial subluxation; the clue is in the intractable nature of atlantoaxial subluxation. Other symptoms that may help in distinguishing between the primary disease and secondary complication includes radicular pain, Lhermitte’s sign (shocklike sensations through the torso or into the extremities), loss of fine motor control or gait changes, though these features are uncommon in the early stages of atlantoaxial subluxation. Clinical examination should be focused on eliciting signs of myelopathy and associated complications caused by localised compression (e.g., cranial nerve palsies, horner’s syndrome); one report of an patient with ankylosing spondylitis with vertical atlantoaxial subluxation had bilateral hypoglossal nerve palsy 15.

Compression of the C2 sensory fibers supplying the nucleus of the spinal trigeminal tract can cause facial pain. Compression of the C2 sensory fibers supplying the greater auricular nerve may result in ear pain. Occipital neuralgia results from compression of the C2 sensory fibers supplying the greater occipital nerve. A history of myelopathic symptoms should be sought carefully. Patients may experience weakness, decreased endurance, gait difficulty, paresthesias of the hands, and loss of fine dexterity. Patients with involvement may experience and, eventually, incontinence.

Vertebrobasilar insufficiency may be found, particularly in patients with atlantoaxial instability. Complaints may include vertigo, loss of equilibrium, visual disturbances, tinnitus, and dysphagia. Similar symptomatology can also be caused by mechanical compression of the brainstem. In some patients, neck motion can elicit shocklike sensations through the torso or into the extremities (i.e, Lhermitte sign).

Pannus rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis

The physical diagnosis of these patients frequently is confounded by the severity of their peripheral rheumatoid involvement. Weakness in these patients can also be due to tenosynovitis, tendon rupture, muscular atrophy, peripheral nerve entrapment, or articular involvement, making neurologic impairment less obvious. Signs of myelopathy should raise suspicion of cervical involvement. Rarely, cranial nerve dysfunction can occur secondary to compression of the medullary nuclei by the odontoid. Other rare findings in patients with advanced brainstem compression include vertical nystagmus and Cheyne-Stokes respirations.

Classification of neurologic deficits

The Ranawat classification 16 can be used to categorize patients with rheumatoid myelopathy based on their clinical history and physical findings (see below). This classification has some utility in determining the potential for neurologic recovery following surgery and is categorized as follows 16:

- Class 1 – No neural deficit

- Class 2 – Subjective weakness, dysesthesias, and hyperreflexia

- Class 3A – Objective weakness and long-tract signs; patient remains ambulatory

- Class 3B – Objective weakness and long-tract signs; patient no longer ambulatory

Diagnostic studies

Rheumatoid factor seropositivity has been correlated with more extensive cervical involvement (rheumatoid spondylitis, ankylosing spondylitis). The use of the rheumatoid factor as a predictor of neurologic involvement has not been established; therefore, it does not have a role in the surveillance of patients with rheumatoid arthritis with cervical involvement.

All patients with rheumatoid arthritis should have radiographic examination of the cervical spine because cervical involvement (rheumatoid spondylitis, ankylosing spondylitis) can remain asymptomatic. Imaging modalities include plain radiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), polytomography, and computed tomography (CT) scanning. Although prediction of the onset of myelopathy in any particular patient is difficult, studies of large populations of patients have sought to establish parameters for predicting neurologic involvement via imaging studies 17.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has provided an increased ability to visualize the extent of spinal cord compression, particularly when due to pannus 18. Dvorak and colleagues 19 showed that two thirds of patients with atlantoaxial subluxation have a pannus of greater than 3 mm in diameter. Therefore, the bony canal diameter measured on plain radiographs may not represent the true space available for the cord. Kawaida et al. 20 demonstrated spinal cord compression in all patients with rheumatoid arthritis when the space available for the cord (as measured on MRI) was 13 mm or less.

Using MRI, the cervicomedullary angle is an effective indicator of cord distortion from superior migration of the odontoid. This angle incorporates lines drawn along the anterior aspects of the cervical cord and along the medulla. The normal range is 135-175°. Angles less than 135° indicate basilar invagination and have been associated with myelopathy.

Polytomography and CT Scanning

Historically, tomograms were useful for quantitating the degree of basilar invagination and to measure the anterior and posterior atlantodental intervals more accurately in patients with abnormal radiographs. However, computed tomography (CT) scanning with sagittal and coronal reformatting has largely supplanted biplanar tomography. A CT scan combined with intrathecal contrast provides excellent bony detail and the ability to detect spinal cord compression from synovial pannus.

Although the noninvasive nature of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has made it the preferred modality for this type of evaluation, CT myelography is useful for patients with contraindications to MRI.

Pannus rheumatoid arthritis treatment

Nonsurgical management

Nonoperative treatment of rheumatoid involvement of the cervical spine (rheumatoid spondylitis, ankylosing spondylitis) is supportive. Early aggressive medical management is important in the global sense, as cervical involvement has been correlated with disease activity. Collars can be used for comfort purposes. Rigid cervical collars most likely do not prevent subluxation; however, they may prevent reduction of a deformity by limiting extension 21. Skin sensitivity in this population also causes problems with rigid orthoses. Patients being monitored need careful surveillance for long-tract signs or for radiographic findings suggesting impending neurologic compromise

Surgical management

The identification of a subset of patients with impending neurologic deficit has been elusive due to the poor correlation of neurologic symptoms with radiographic indicators of instability. Therefore, universally accepted surgical indications have been slow to develop. However, patients with rheumatoid arthritis or, particularly, rheumatoid spondylitis (ankylosing spondylitis) who have refractory pain, clearly evident neurologic compromise, or intrinsic spinal cord signal changes on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are generally candidates for surgical intervention.

Controversy surrounds treatment for patients with little or no pain, no neural deficit, and radiographs suggestive of instability. To facilitate understanding of the operative indications and perioperative details, categorization of these patients by their pathologic lesion is helpful 22.

Contraindications to surgery for rheumatoid spondylitis (ankylosing spondylitis) include medical conditions that suggest the patient would not tolerate the stress of surgery, such as unstable angina or a recent myocardial infarction or stroke 23. Active infection with likely bacteremia would also be a relative contraindication to surgery, especially in the setting of planned instrumentation. The patient’s medical condition should be optimized before proceeding with any planned surgical intervention.

Postsurgical complications

Rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic disorder, and patients may have varying degrees of generalized debilitation 24. The postoperative course of such patients can be complicated by fragile skin and poor wound healing. Poor preoperative nutritional status and corticosteroid dependence may potentiate wound-healing problems and predispose toward infection 25.

Some airways are difficult to intubate. Excessive trauma during intubation may be responsible for postoperative breathing problems. Wattenmaker et al. 26 reported a 14% incidence of upper airway obstruction after extubation in patients intubated without fiberoptic assistance, compared with a 1% incidence in patients intubated fiberoptically. The perioperative mortality rate has been reported to be as high as 5-10%.

References- Lagares A, Arrese I, Pascual B, Gòmez PA, Ramos A, Lobato RD. Pannus resolution after occipitocervical fusion in a non-rheumatoid atlanto-axial instability. Eur Spine J. 2005;15(3):366-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3489286/

- Retro-dental reactive lesions related to development of myelopathy in patients with atlantoaxial instability secondary to Os odontoideum. Chang H, Park JB, Kim KW, Choi WS. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000 Nov 1; 25(21):2777-83.

- [Reduction of periodontoid masses following posterior arthrodesis: review of two new cases not linked to rheumatoid arthritis]. Joly-Torta M, Martín-Ferrer S, Rimbau-Muñoz J, Domínguez C. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2004 Dec; 15(6):553-63; discussion 563-4.

- Sommer OJ, Kladosek A, Weiler V et-al. Rheumatoid arthritis: a practical guide to state-of-the-art imaging, image interpretation, and clinical implications. Radiographics. 25 (2): 381-98. doi:10.1148/rg.252045111

- Pre- and postoperative MR imaging of the craniocervical junction in rheumatoid arthritis. Larsson EM, Holtås S, Zygmunt S. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989 Mar; 152(3):561-6.

- Occipitocervical fusion for reduction of traumatic periodontoid hypertrophic cicatrix. Case report. Lansen TA, Kasoff SS, Tenner MS. J Neurosurg. 1990 Sep; 73(3):466-70.

- Retro-odontoid soft tissue mass associated with atlantoaxial subluxation in an elderly patient: a case report. Isono M, Ishii K, Kamida T, Fujiki M, Goda M, Kobayashi H. Surg Neurol. 2001 Apr; 55(4):223-7.

- Pannus at the cranio-cervical junction: CT and MRI findings. https://radiopaedia.org/cases/pannus-at-the-cranio-cervical-junction-ct-and-mri-findings?lang=us

- da Corte FC, Neves N. Cervical spine instability in rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014 Jul. 24 Suppl 1:S83-91.

- Morizono Y, Sakou T, Kawaida H. Upper cervical involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Spine. 1987 Oct. 12(8):721-5.

- Clarke MJ, Cohen-Gadol AA, Ebersold MJ, Cabanela ME. Long-term incidence of subaxial cervical spine instability following cervical arthrodesis surgery in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Surg Neurol. 2006 Aug. 66(2):136-40; discussion 140.

- Kraus DR, Peppelman WC, Agarwal AK, et al. Incidence of subaxial subluxation in patients with generalized rheumatoid arthritis who have had previous occipital cervical fusions. Spine. 1991 Oct. 16(10 Suppl):S486-9.

- Posttraumatic atlanto-axial subluxation and myelopathy. Efficacy of anterior decompression. Moskovich R, Crockard HA. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990 Jun; 15(6):442-7.

- EL Maghraoui A, Bensabbah R, Bahiri R, et al. Cervical spine involvement in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheum 2003;22:94–8

- Chien JT, Chen IH, Lin KH. Atlantoaxial rotatory dislocation with hypoglossal nerve palsy in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg (American) 2005;87:1587–90

- Ranawat CS, O’Leary P, Pellicci P, et al. Cervical spine fusion in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979 Oct. 61(7):1003-10.

- Younes M, Belghali S, Kriaa S, et al. Compared imaging of the rheumatoid cervical spine: prevalence study and associated factors. Joint Bone Spine. 2009 Jul. 76(4):361-8.

- Castro S, Verstraete K, Mielants H. Cervical spine involvement in rheumatoid arthritis: a clinical, neurological and radiological evaluation. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1994 Jul-Aug. 12(4):369-74.

- Dvorak J, Grob D, Baumgartner H, et al. Functional evaluation of the spinal cord by magnetic resonance imaging in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and instability of upper cervical spine. Spine. 1989 Oct. 14(10):1057-64.

- Kawaida H, Sakou T, Morizono Y, Yoshkuni N. Magnetic resonance imaging of upper cervical disorders in rheumatoid arthritis. Spine. 1989 Nov. 14(11):1144-8.

- Kauppi M, Anttila P. A stiff collar for the treatment of rheumatoid atlantoaxial subluxation. Br J Rheumatol. 1996 Aug. 35(8):771-4.

- Gillick JL, Wainwright J, Das K. Rheumatoid Arthritis and the Cervical Spine: A Review on the Role of Surgery. Int J Rheumatol. 2015. 2015:252456.

- Zha AM, Di Napoli M, Behrouz R. Prevention of Stroke in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2015 Dec. 15 (12):77.

- Heyde CE, Fakler JK, Hasenboehler E, et al. Pitfalls and complications in the treatment of cervical spine fractures in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Patient Saf Surg. 2008 Jun 6. 2:15.

- Pahys JM, Pahys JR, Cho SK, et al. Methods to decrease postoperative infections following posterior cervical spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013 Mar 20. 95(6):549-54.

- Wattenmaker I, Concepcion M, Hibberd P, Lipson S. Upper-airway obstruction and perioperative management of the airway in patients managed with posterior operations on the cervical spine for rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994 Mar. 76(3):360-5.