Peanut allergy baby

Peanut allergy is an adverse immune response to a peanut allergen. Reactions include:

- Systemic immunoglobulin E (IgE) mediated type I immediate hypersensitivity reaction (anaphylaxis) 1

- Oral allergy syndrome — a localised IgE-mediated allergy caused by fresh fruits, vegetables, and nuts, with symptoms confined to the lips, mouth, and throat 2

- Non-IgE-mediated allergy — this response can take hours to days to occur and results in gastrointestinal symptoms (vomiting, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain) 3.

Peanut allergy is the most common cause of food-related anaphylaxis 3.

To date, the recommended management of peanut allergy relies on avoidance of peanut ingestion. Unfortunately, severe reactions such as anaphylaxis may occur despite best efforts in avoidance. Epinephrine is the first-line medication for the treatment of anaphylaxis. Intramuscular (IM) or intravenous (IV) epinephrine should be administered, although the IM route is preferred, with injection placement in the lateral thigh. IV administration ideally should be done in the inpatient setting with appropriate monitoring 4. Antihistamines, steroids, and bronchodilators, may also be used, but it is essential to realize these medications do not treat anaphylaxis, rather they are adjunctive therapies for anaphylaxis management. IV fluids should be provided to prevent and treat tissue hypo-perfusion. In rare cases, the patient may require intubation for airway protection. Severe cases of anaphylaxis should be admitted and monitored at least overnight until stable. Biphasic anaphylaxis may occur in some cases where symptoms recur up to 8 hours after the initial reaction. The treating physician should take this into account before discharge 5. In less severe presentations the patient can be observed in the emergency room after standard treatment, and with sufficient improvement safely discharged home.

Although avoidance is the mainstay of treatment, new strategies are being tested to prevent food allergy. Peanut immunotherapy clinical trials have been promising to date using incremental ingestion of small amounts of peanut over time with oral immunotherapy (OIT). The goal of oral immunotherapy may be either to prevent a reaction if accidental peanut ingestion occurs or to induce tolerance where the patient can regularly ingest peanut safely 6. Epicutaneous immunotherapy is another desensitization method tested where peanut is transdermally introduced over time to build up a tolerance.

Immunization with plasmid DNA encoding food allergens is a novel method to treat peanut allergy. However, this approach requires a large amount of plasmid DNA required for vaccination.

Mutated peanut protein substitutes is another way to manage peanut allergy.

Finally, sublingual immunotherapy involves placing emulsified purified peanut protein under the tongue for 120 seconds and then swallowing. Data show that this can help prevent peanut allergic reactions with time.

Introducing peanuts or peanut butter to baby

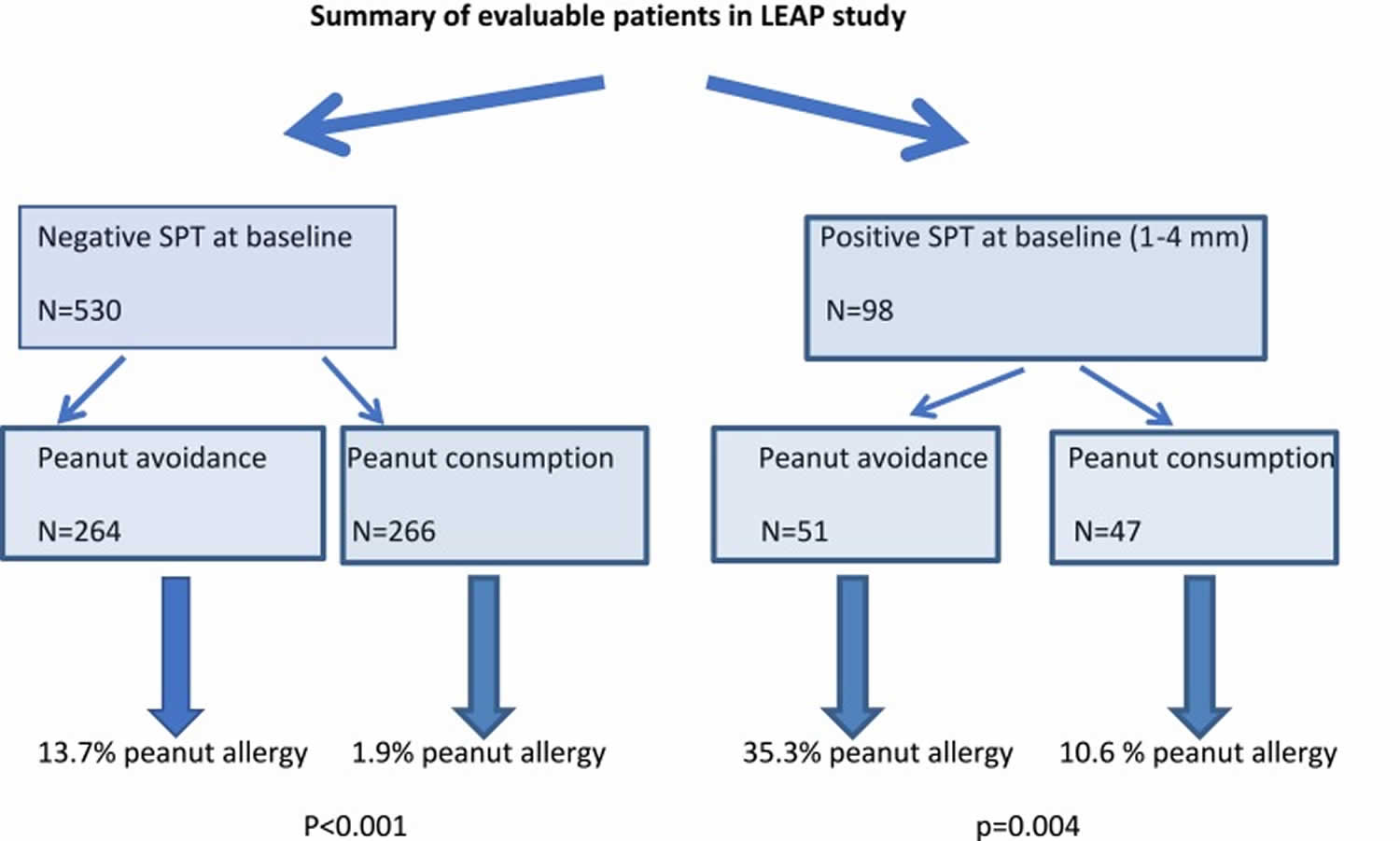

Recent efforts in peanut allergy prevention have focused on the concept of early oral introduction of peanut protein, and preservation of the skin barrier to reduce the chance of epicutaneous sensitization. Two large studies published in the past 5 years have demonstrated the potential protective effect of early peanut introduction. The most persuasive of these studies, albeit in a high-risk population, was the LEAP study (Learning Early about Peanut Allergy) 7, a landmark trial in the realm of peanut allergy prevention 8. The LEAP study (Learning Early about Peanut Allergy study) enrolled 640 children at high risk of peanut allergy, which was defined for this study as infants between 4 and 11 months of age with severe eczema and/or egg allergy. At study entry, LEAP participants were stratified according to skin prick test result to peanut into those with a negative skin prick test response (n=530), a primary prevention group, and those with a measurable skin prick test response (1–4 mm), n=98, a secondary prevention group as they were considered sensitized but not allergic to peanut at study entry. Participants with a skin prick test of greater than or equal to 5 mm were excluded because of their high risk of established peanut allergy, although these patients did not undergo oral food challenges to determine if they were truly peanut-allergic. Patients were randomized to consume at least 2 g of peanut protein thrice weekly or avoid peanut-containing food until 5 years of age, at which stage a peanut oral food challenges was performed. Infants randomized to consume peanut ingested a median of 7.7 g peanut protein per week during the first 2 years of the trial.

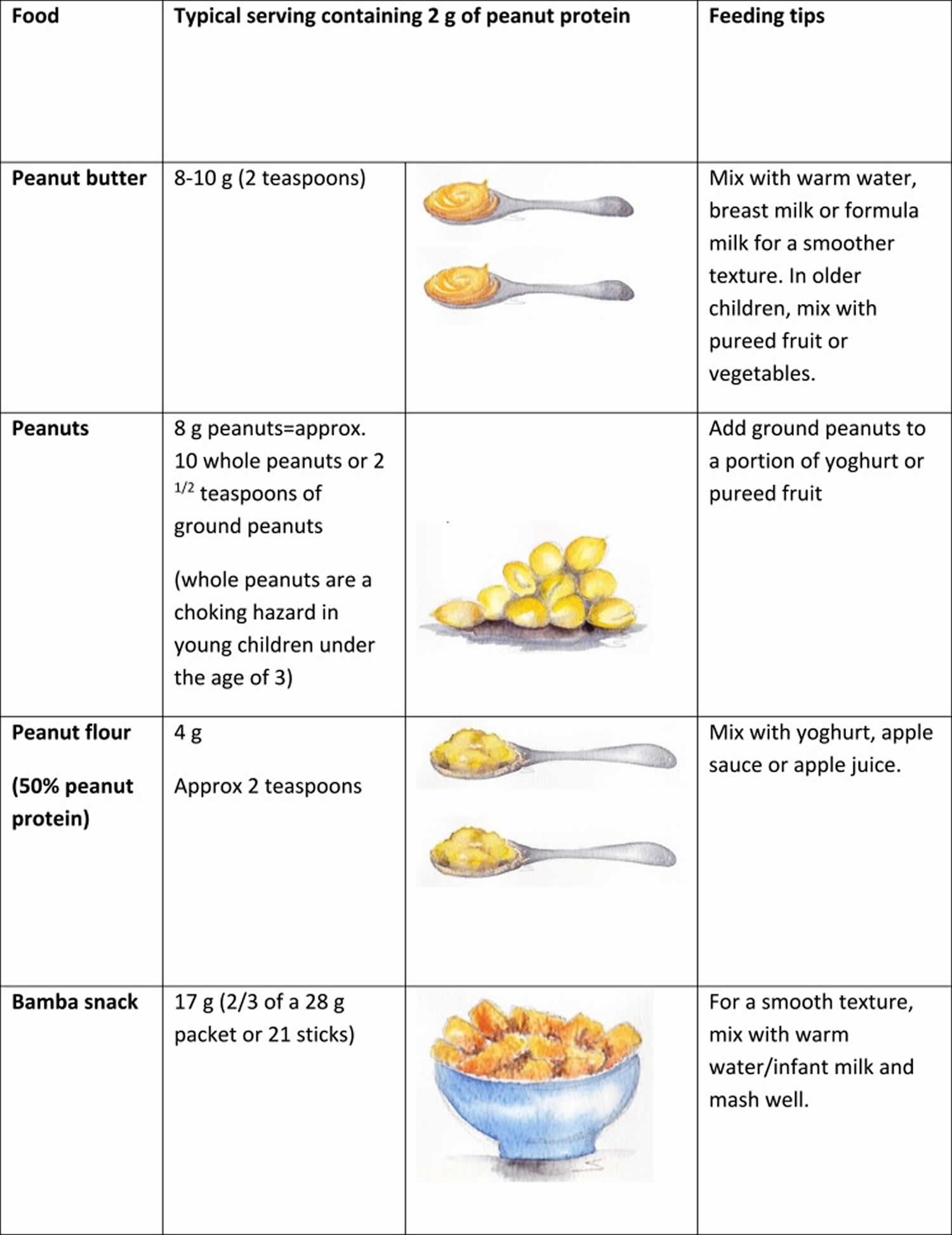

The LEAP study 7 suggests that the first dose of peanut protein should be a cumulative dose of around 2 g of peanut protein. Thereafter, the total minimum amount of peanut protein should be 6–7 g per week, consumed over three or more feedings per week. Figure 3 demonstrates pictorially that this is a substantial amount of peanut protein for young infants to eat in one sitting. However, it is not yet known if other amounts and frequencies of ingesting peanut would have the same results.

Figure 1 demonstrates the outcome of the study, with a significant protective effect of early peanut introduction in high-risk infants 9.

The LEAP-ON study 10 demonstrated the long-term persistence of oral tolerance to peanut achieved in the LEAP trial when peanut consumers subsequently avoided peanut for 1 year from 60 to 72 months. A further analysis on nutrition in the LEAP cohort 11 showed that introduction of peanut did not affect the frequency or duration of breastfeeding and did not influence growth or nutrition.

The significant reduction in peanut allergy in the early consumption group led to international effort to develop practical clinical recommendations on peanut allergy prevention 12. Although many existing infant feeding guidelines prior to 2015 already suggested the introduction of allergenic foods from 4 to 6 months onwards, these did not specifically emphasize that avoidance may be harmful. A consensus statement regarding the implementation of LEAP findings was published after the LEAP findings in 2015 on behalf of several international professional societies 13. In addition, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases published addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States in 2017 14, an addendum to the 2010 “Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States.”

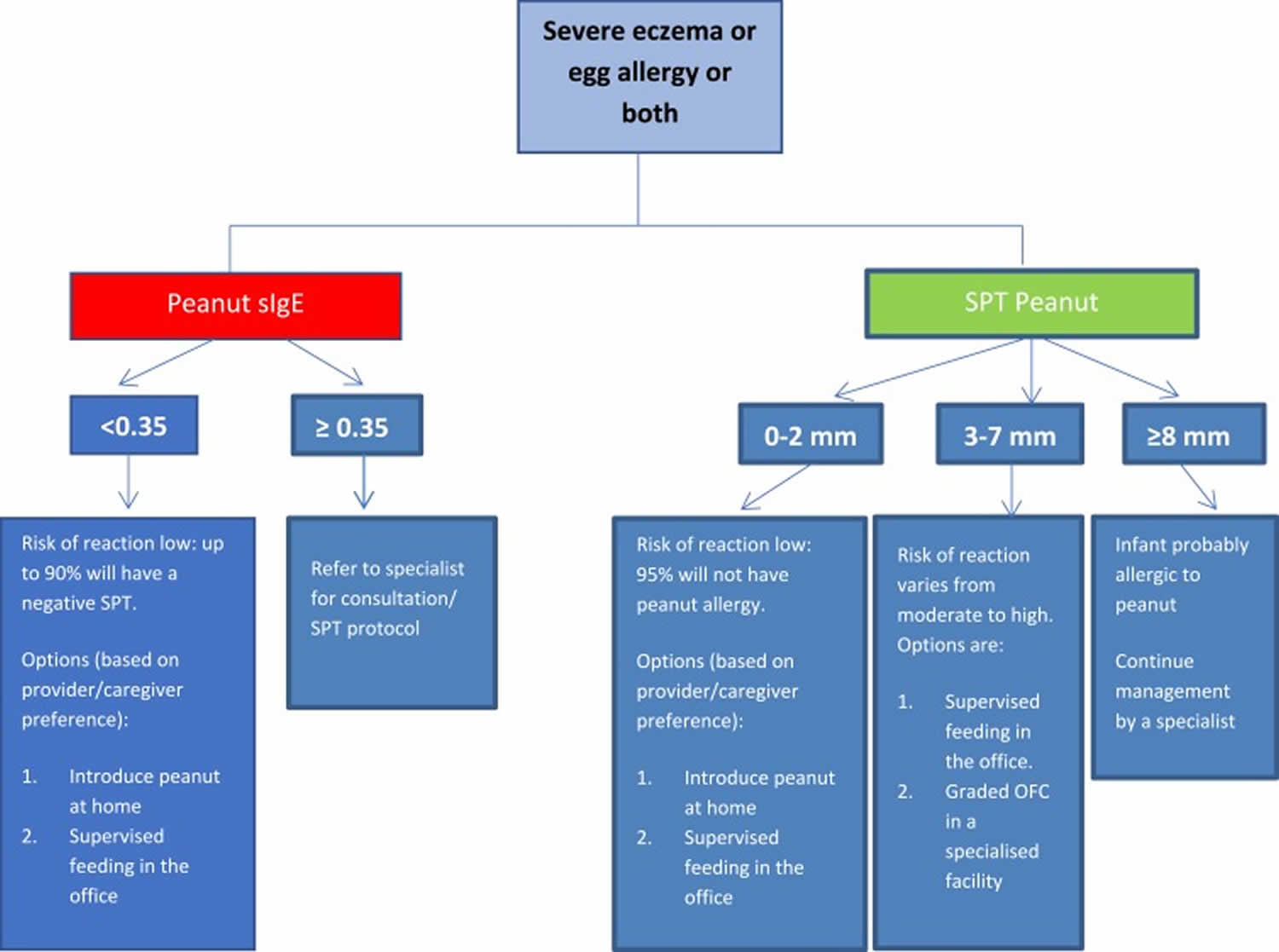

Table 1 summarizes the general recommendations for peanut introduction in infants according to risk level for peanut allergy 13 and Figure 2 demonstrates the recommended pathway of peanut introduction in high-risk infants 9.

Health and economic benefit modelling found that early peanut introduction is cost-effective when compared to delaying peanut introduction beyond 12 months 15.

The Enquiring about tolerance study (EAT study) 16 is another recent study looking into the introduction of a variety of allergenic foods in a more unselected population of infants. This study enrolled 1303 exclusively breastfed infants at 3 months of age and randomized half to exclusively breastfeed till about 6 months of age and then introduce solids according to family preference (the standard introduction group); and half to consume six allergenic foods (peanut, cow’s milk, egg, wheat, fish, sesame) twice weekly from study enrolment (early introduction group). Per protocol analysis found peanut allergy prevalence to be significantly lower in the early intervention group (0% v 2.5%). There was a trend towards an effect in the intention to treat analysis. A secondary intention-to-treat analysis showed that early introduction was effective in preventing the development of food allergy in specific groups of infants at increased risk of food allergy: those sensitized to any food at enrolment, and those with moderate eczema at enrolment 17. A follow-up of EAT children at 8 years of age will be performed to study a more long-term outcome of early allergen introduction.

Figure 1. Summary of Learning Early about Peanut Allergy study (LEAP study) outcome

Abbreviations: LEAP study = Learning Early about Peanut Allergy study; SPT = skin prick test

[Source 18 ]Figure 2. Peanut protein introduction in infants at high risk of peanut allergy

Footnote: To minimize a delay in peanut introduction for children who may test negative, testing for peanut-specific IgE (peanut sIgE) may be the preferred initial approach in certain health care settings. Food allergen panel testing or the addition of sIgE testing for foods other than peanut is not recommended due to poor positive predictive value

Abbreviations: peanut sIgE = peanut-specific IgE; SPT = skin prick test

[Source 9 ]Figure 3. Typical peanut-containing foods and portion sizes

[Source 9 ]Table 1. Recommendations for peanut introduction in infants according to risk stratification

| Infant Criteria | Recommendations | Earliest Age of Peanut Introduction |

|---|---|---|

| No eczema and no other food allergies | Introduce peanut-containing foods | In accordance with family preferences and cultural practices, but no need to delay beyond 6 months |

| Mild-to-moderate eczema | Introduce peanut-containing foods | Around 6 months |

| Severe eczema,a egg allergy or both | Evaluation by specific IgE (sIgE) measurement and/or skin prick test, and if necessary, an oral food challenge. Based on test results, introduce peanut-containing foods (see Figure 2 and Table 2) | Around 4–6 months |

Footnote: (a) Severe eczema is defined as persistent or frequently recurring eczema with typical morphology and distribution assessed by a health-care provider, requiring frequent need for prescription strength topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors despite appropriate use of emollients.

[Source 18 ]Instructions for Home Feeding of peanut protein for infants at low risk of an allergic reaction to peanut

These instructions for home feeding of peanut protein are provided by your doctor. You should discuss any questions that you have with your doctor before starting. These instructions are meant for feeding infants who have severe eczema or egg allergy and were allergy tested (blood test, skin test, or both) with results that your doctor considers safe for you to introduce peanut protein at home (low risk of allergy).

General instructions

- Feed your infant only when he or she is healthy; do not do the feeding if he or she has a cold, vomiting, diarrhea, or other illness.

- Give the first peanut feeding at home and not at a day care facility or restaurant.

- Make sure at least 1 adult will be able to focus all of his or her attention on the infant, without distractions from other children or household activities.

- Make sure that you will be able to spend at least 2 h with your infant after the feeding to watch for any signs of an allergic reaction.

Feeding your infant

- Prepare a full portion of one of the peanut-containing foods from the recipe options below.

- Offer your infant a small part of the peanut serving on the tip of a spoon.

- Wait 10 min.

- If there is no allergic reaction after this small taste, then slowly give the remainder of the peanut-containing food at the infant’s usual eating speed.

What are symptoms of an allergic reaction? What should I look for?

- Mild symptoms can include:

- a new rash or

- a few hives around the mouth or face

- More severe symptoms can include any of the following alone or in combination:

- lip swelling

- vomiting

- widespread hives (welts) over the body

- face or tongue swelling

- any difficulty breathing

- wheeze

- repetitive coughing

- change in skin color (pale, blue)

- sudden tiredness/lethargy/seeming limp

If you have any concerns about your infant’s response to peanut, seek immediate medical attention/call your local emergency number.

Four recipe options, each containing approximately 2 g of peanut protein

Note: Teaspoons and tablespoons are US measures (5 and 15 mL for a level teaspoon or tablespoon, respectively).

- Option 1: Bamba (Osem, Israel), 21 pieces (approximately 2 g of peanut protein)

Note: Bamba is named because it was the product used in the LEAP trial and therefore has proven efficacy and safety. Other peanut puff products with similar peanut protein content can be substituted.- For infants less than 7 months of age, soften the Bamba with 4 to 6 teaspoons of water.

- For older infants who can manage dissolvable textures, unmodified Bamba can be fed. If dissolvable textures are not yet part of the infant’s diet, softened Bamba should be provided.

- Option 2: Thinned smooth peanut butter, 2 teaspoons (9–10 g of peanut butter; approximately 2 g of peanut protein)

- Measure 2 teaspoons of peanut butter and slowly add 2 to 3 teaspoons of hot water.

- Stir until peanut butter is dissolved, thinned, and well blended.

- Let cool.

- Increase water amount if necessary (or add previously tolerated infant cereal) to achieve consistency comfortable for the infant.

- Option 3: Smooth peanut butter puree, 2 teaspoons (9–10 g of peanut butter; approximately 2 g of peanut protein)

- Measure 2 teaspoons of peanut butter.

- Add 2 to 3 tablespoons of pureed tolerated fruit or vegetables to peanut butter. You can increase or reduce volume of puree to achieve desired consistency.

- Option 4: Peanut flour and peanut butter powder, 2 teaspoons (4 g of peanut flour or 4 g of peanut butter powder; approximately 2 g of peanut protein)

Note: Peanut flour and peanut butter powder are 2 distinct products that can be interchanged because they have a very similar peanut protein content.- Measure 2 teaspoons of peanut flour or peanut butter powder.

- Add approximately 2 tablespoons (6–7 teaspoons) of pureed tolerated fruit or vegetables to flour or powder. You can increase or reduce volume of puree to achieve desired consistency.

For health care providers: In-office supervised feeding protocol using 2 g of peanut protein

General instructions

- These recommendations are reserved for an infant defined in guideline 1 as one with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both and with negative or minimally reactive (1 to 2 mm) Skin Prick Test responses and/or peanut sIgE levels of less than 0.35 kUA/L. They also may apply to the infant with a 3 to 7 mm Skin Prick Test response if the specialist health care provider decides to conduct a supervised feeding in the office (as opposed to a graded oral graded food challenge in a specialized facility [see Figure 1 above].

These recommendations can also be followed for infants with mild-to-moderate eczema, as defined in guideline 2, when caregivers and health care providers may desire an in-office supervised feeding. - Proceed only if the infant shows no evidence of any concomitant illness, such as an upper respiratory tract infection.

- Start with a small portion of the initial peanut serving, such as the tip of a teaspoon of peanut butter puree/softened Bamba.

- Wait 10 min; if there is no sign of reaction after this small portion is given, continue gradually feeding the remaining serving of peanut-containing food (see options below) at the infant’s typical feeding pace.

- Observe the infant for 30 min after 2 g of peanut protein ingestion for signs/symptoms of an allergic reaction.

Four recipe options, each containing approximately 2 g of peanut protein

Note: Teaspoons and tablespoons are US measures (5 and 15 mL for a level teaspoon or tablespoon, respectively).

- Option 1: Bamba (Osem, Israel), 21 pieces (approximately 2 g of peanut protein)

Note: Bamba is named because it was the product used in the LEAP trial and therefore has known peanut protein content and proven efficacy and safety. Other peanut puffs products with similar peanut protein content can be substituted for Bamba.- For infants less than 7 months of age, soften the Bamba with 4 to 6 teaspoons of water.

- For older infants who can manage dissolvable textures, unmodified Bamba can be fed. If dissolvable textures are not yet part of the infant’s diet, softened Bamba should be provided.

- Option 2: Thinned smooth peanut butter, 2 teaspoons (9–10 g of peanut butter; approximately 2 g of peanut protein)

- Measure 2 teaspoons of peanut butter and slowly add 2 to 3 teaspoons hot water.

- Stir until peanut butter is dissolved and thinned and well blended.

- Let cool.

- Increase water amount if necessary (or add previously tolerated infant cereal) to achieve consistency comfortable for the infant.

- Option 3: Smooth peanut butter puree, 2 teaspoons (9–10 g of peanut butter; approximately 2 g of peanut protein)

- Measure 2 teaspoons of peanut butter.

- Add 2 to 3 tablespoons of previously tolerated pureed fruit or vegetables to peanut butter. You can increase or reduce volume of puree to achieve desired consistency.

- Option 4: Peanut flour and peanut butter powder, 2 teaspoons (4 g of peanut flour or 4 g of peanut butter powder; approximately 2 g of peanut protein)Note: Peanut flour and peanut butter powder are 2 distinct products that can be interchanged because they have, on average, a similar peanut protein content.

- Measure 2 teaspoons of peanut flour or peanut butter powder.

- Add approximately 2 tablespoons (6–7 teaspoons) of pureed tolerated fruit or vegetables to flour or powder. You can increase or reduce the volume of puree to achieve desired consistency.

Suggested procedure for introduction of peanut before 12 months (not before 4 months) when the infant is developmentally ready for solid food – under medical supervision (e.g. in doctor rooms) or at home 19

- Children in the high risk group should be brought to a specialist for peanut-specific IgE (sIgE) or skin prick testing to decide the safest way to introduce peanuts. If the child does not show signs of peanut allergy at the time of testing, the healthcare professional will create a plan with the child’s caretakers to introduce foods containing peanuts at home or undertake a supervised feeding in the healthcare provider’s office. The guidelines recommend starting the introduction process as early as 4 to 6 months.

- Children in the second highest risk group, with mild to moderate eczema, should be introduced to peanuts around 6 months to reduce the risk of peanut allergy.

- Children in the lowest risk group, with no signs of eczema or food allergy, can be introduced to peanuts when age-appropriate and according to family and cultural preferences.

- Rub a small amount of smooth peanut butter/paste on the inside of the infant’s lip (not on their skin).

- If there is no allergic reaction after a few minutes, feed the infant ¼ teaspoon of smooth peanut butter/paste (as a spread or mixed into other food that the infant is already eating or mixed with a few drops of warm water) and observe for 30 minutes.

- If there is no allergic reaction, give ½ teaspoon of smooth peanut butter/paste and observe for a further 30 minutes.

- If there is no allergic reaction, parents should continue to include peanut in their infant’s diet in gradually increasing amounts at least weekly, as it is important to continue to feed peanut to the infant as a part of a varied diet.

- If there is an allergic reaction at any step, stop feeding peanut to the infant and seek medical advice (if at home).

- An allergic reaction should be treated by following the Anaphylaxis Emergency Action Plan (watch the YouTube video and see Figure 1)

- Mild or moderate allergic reactions (swelling of the lips, eyes or face, urticaria or vomiting) can be treated using non-sedating antihistamines such as cetirizine, loratadine or desloratidine. To avoid confusion with the symptoms of anaphylaxis, sedating antihistamines should not be used to treat allergic reactions.

- If there are symptoms of anaphylaxis (difficult/noisy breathing, pale and floppy, swollen tongue) treat with adrenaline and call an ambulance immediately.

- If an infant has an allergic reaction they may be referred to a clinical immunology/allergy specialist for further investigations

Further information

- Some infants will develop peanut allergy despite following National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases guidelines.

- Whilst severe allergic reactions have been reported, to date there have been no case reports of fatality to peanut ingestion in infants under 12 months of age.

- Some infants can have an allergic reaction on the first (or subsequent) oral feeding of peanut, as they may already be sensitized to peanut prior to any known oral exposure before 12 months of age.

- Never smear or rub food on infant skin, especially if they have eczema, as this will not help to identify possible food allergies. This could also sensitize the infant, who may then develop an allergy to that food.

- Screening programs for infants with severe eczema and/or egg allergy prior to introduction of peanut have been proposed in the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Guidelines 20. There are concerns that allergy tests are not suitable for screening and referrals may delay peanut introduction to high risk infants 21.

Challenges in peanut allergy prevention

- There is controversy around the best way forward in those infants with very minimal reactions (for example, a few hives around the mouth in an otherwise asymptomatic infant), and those who only react at a higher dose but seem to tolerate a lower dose of peanut protein. The potential benefit of continued exposure of such infants to much lower, tolerated levels of peanut protein, with potential slow increases over time, remains to be explored.

- The minimum length of treatment to induce the tolerogenic effect is not known. The effect of sporadic feeding of peanut, and potential disadvantages of premature discontinuation of regular peanut feeding are currently unknown and may only become clear in “real-life” setting. Certainly, in the author’s practice, we have seen several cases of early tolerance in high-risk patients, followed by periods of erratic intake which eventually culminated in reactivity.

- The LEAP study included a high-risk population and cannot make recommendations on the benefit of early peanut introduction in the general or low-risk populations. Further follow-up data on the more “unselective” EAT study are awaited.

- The LEAP-style approach should be adapted according to country, community or even family-setting to promote the adherence. This would ideally require thoughtful tailoring of the protocol to the specific situation of each child.

- The longstanding notion that delayed introduction of certain foods may help reduce allergies will have to be “undone” as we learn now that avoidance may in fact be harmful. This will need to start at the primary care levels, and getting the message out there will require widespread efforts. The distribution of the message that earlier peanut consumption has potential advantages has already borne fruit in countries such as Australia: from 2007 to 2011, fewer than 3 in 10 Australian infants consumed peanut by the age of 12 months. Changes in infant feeding guidelines in 2016 resulted in nearly 9 in 10 infants consuming peanut by the age of 12 months in 2018 22.

- The practical implications of screening high-risk infants for peanut allergy and arranging suitable incremental oral food challenges in “grey area” cases are significant and will place a burden on health-care facilities. A delay in the introduction of solids whilst awaiting an allergy screening appointment can in itself increasing allergy risk.

Future prospects in peanut allergy prevention

Further research trials that explore real-life application of early peanut introduction guidelines are needed, as well as the potential role of early peanut introduction in the general population.

Preservation of the skin barrier to minimize transcutaneous entry of allergens

Skin barrier dysfunction has been shown to play a role in food allergy. The dual allergen hypothesis proposes that allergic sensitization may occur through the skin, but tolerance may be induced via the gut 23.

There is evidence that environmental peanut exposure increases the risk of peanut sensitization and peanut allergy, particularly in those with atopic dermatitis and filaggrin loss of function mutations 24. Studies have shown that early emollient therapy may reduce the chances of developing eczema 25.

Studies are now underway to examine whether early emollient application can prevent food allergy sensitization. The PEBBLES pilot study 26 showed a trend towards reduced food sensitization with regular emollient therapy. Larger and robust studies on skin barrier preservation and food allergy prevention are underway.

The LEAP study 7 demonstrated that Staphylococcus aureus on the skin is associated with food sensitization and allergy, independent of eczema severity. Prevention and prompt treatment of Staphylococcus aureus in children with eczema may therefore be another means of enhancing the integrity of the skin barrier and maintaining tolerance to allergens 27.

Baby peanut allergy causes

According to the leading experts in allergy, an allergic reaction begins in the immune system. Peanut allergy occurs when your immune system mistakenly identifies peanut proteins as something harmful. Direct or indirect contact with peanuts causes your immune system to release symptom-causing chemicals into your bloodstream. Your immune system protects you from invading organisms that can cause illness. If you have an allergy, your immune system mistakes an otherwise harmless substance (e.g. peanut) as an invader. This substance is called an allergen. The immune system overreacts to the allergen by producing Immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies. These antibodies travel to cells that release histamine and other chemicals, causing an allergic reaction.

Food allergy classifies as a type 1 IgE mediated hypersensitivity reaction. Initial sensitization to peanut stimulates the production of peanut-specific IgE antibodies. The allergy to peanuts is to due to low molecular weight proteins that are resistant to heat, proteases and denaturants. Eleven peanut allergens have been described (Ara h 1-11). The major peanut antigens identified by the specific antibodies response include AraH1, H2, H3. In a sensitized individual, peanut ingestion can trigger specific IgE antibody cross-linking to IgE receptors on effector cells such as basophils and mast cells, which triggers mediator release such as histamine and a variety of cytokines and chemokines. Inflammatory cell recruitment ensues to propagate the allergic response 28.

An allergic reaction typically triggers symptoms in the nose, lungs, throat, sinuses, ears, lining of the stomach or on the skin. For some people, allergies can also trigger symptoms of asthma. In the most serious cases, a life-threatening reaction called anaphylaxis can occur.

Exposure to peanuts can occur in various ways:

- Direct contact. The most common cause of peanut allergy is eating peanuts or peanut-containing foods. Sometimes direct skin contact with peanuts can trigger an allergic reaction.

- Cross-contact. This is the unintended introduction of peanuts into a product. It’s generally the result of a food being exposed to peanuts during processing or handling.

- Inhalation. An allergic reaction may occur if you inhale dust or aerosols containing peanuts, from a source such as peanut flour or peanut oil cooking spray.

Risk factors for peanut allergy

It isn’t clear why some people develop allergies while others don’t. However, people with certain risk factors have a greater chance of developing peanut allergy.

Peanut allergy risk factors include:

- Age. Food allergies are most common in children, especially toddlers and infants. As you grow older, your digestive system matures, and your body is less likely to react to food that triggers allergies.

- Past allergy to peanuts. Some children with peanut allergy outgrow it. However, even if you seem to have outgrown peanut allergy, it may recur.

- Other allergies. If you’re already allergic to one food, you may be at increased risk of becoming allergic to another. Likewise, having another type of allergy, such as hay fever, increases your risk of having a food allergy.

- Family members with allergies. You’re at increased risk of peanut allergy if other allergies, especially other types of food allergies, are common in your family.

- Atopic dermatitis. Some people with the skin condition atopic dermatitis (eczema) also have a food allergy.

While some people think food allergies are linked to childhood hyperactivity and to arthritis, there’s no evidence to support this.

Baby peanut allergy symptoms

An allergic response to peanuts usually occurs within minutes after exposure. Peanut allergy signs and symptoms can include:

- Runny nose

- Skin reactions, such as hives, redness or swelling

- Itching or tingling in or around the mouth and throat

- Digestive problems, such as diarrhea, stomach cramps, nausea or vomiting

- Tightening of the throat

- Shortness of breath or wheezing

Anaphylaxis: A life-threatening reaction

Peanut allergy is the most common cause of food-induced anaphylaxis, a medical emergency that requires treatment with an epinephrine (adrenaline) injector (EpiPen, Auvi-Q, Twinject) and a trip to the emergency room.

Anaphylaxis signs and symptoms can include:

- trouble breathing or noisy breathing

- difficulty talking more than a few words and/or hoarse voice

- wheeze

- cough

- swelling and tightness of the throat

- collapse

- light-headedness or dizziness

- diarrhea

- tingling in the hands, feet, lips or scalp

- swelling of tongue

- pale and floppy (in young children)

A severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) is a medical emergency. Call your local emergency immediately. Lay the person down. If they have an adrenaline injector and you are able to administer it, do so.

Figure 4. Anaphylaxis Emergency Action Plan

Baby peanut allergy complications

Symptoms can occur within seconds of ingestion, with peak occurrence by 30 minutes but can delay up to 2 hours. Major target organs of an allergic reaction include the skin, gastrointestinal (GI), and respiratory tracts. Skin-related symptoms include urticaria, angioedema, and occasional worsening of existing eczema. Gastrointestinal symptoms include abdominal pain, vomiting, and/or diarrhea. Respiratory symptoms can manifest as repetitive coughing, stridor, and wheezing. Also, it can affect the cardiac and the central nervous systems in the setting of anaphylactic shock whereby diminished tissue perfusion leads to cardiac arrest and syncope 6. Symptom presentation must be interpreted in the context of the patient history, i.e., symptoms are relevant to a food allergy when ingestion occurs in the appropriate time frame expected for food-induced allergic reactions.

Baby peanut allergy diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis of peanut allergy is critical. Sensitization to peanut does not always equate to allergy: cross-reactivity with peanut proteins can lead to false positives, with overdiagnosis leading to unnecessary dietary elimination, stress and reduced quality of life. On the other hand, it is imperative to recognise a true peanut allergy in order to be able to institute the correct management process and equip the patient for unintentional exposures.

Peanut allergy is principally a clinical diagnosis based on the rapid development of allergic symptoms and signs after eating a peanut.

Skin prick testing and serum specific IgE tests to peanut are used to identify sensitization and to confirm the diagnosis 29. Both skin prick tests and specific IgE to peanut are highly sensitive (95%) but specificity is poor (around 60%) 30. A negative test is useful for excluding peanut allergy, whereas a high positive result coupled with a positive history has a high likelihood ratio for peanut allergy. However, for those with intermediate results, further specialized tests such as food challenges may be required to differentiate between asymptomatically sensitized and truly allergic patients. Food challenges are time-consuming, labour-intensive and potentially hazardous, requiring expertise narrowed to certain centers.

Skin prick testing involves placing a drop of peanut allergen on the skin, then pricking the skin to see if a weal is produced within 15 minutes. The British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI) states that a weal ≥ 8 mm in size is highly predictive of peanut allergy. Skin prick testing must be performed in a specialist centre with emergency equipment available in case of anaphylaxis 29.

Serum specific IgE testing, also known as radioallergosorbent testing (RAST), is performed to detect allergen-specific IgE in the blood. Specific IgE ≥ 15 kU/L is highly predictive of peanut allergy 29.

These tests do not predict the severity of clinical allergy 29.

Baby peanut allergy treatment

Currently, stringent avoidance, and quick and correct emergency response to reactions are the mainstay of treatment for peanut allergy.

The treatment of anaphylaxis is a medical emergency entailing the stabilization of airway, breathing, and circulation.

- Intramuscular adrenaline (epinephrine) must be given immediately to patients with signs of shock, airway swelling, or definite difficulty in breathing.

- This may followed by treatment with an antihistamine, a corticosteroid, and other drugs.

Confirmed peanut allergy needs a comprehensive management plan, which should be shared with the patient’s wider family, school, and/or workplace 29.

Peanut oral immunotherapy and more recently sublingual and epicutaneous immunotherapy have been studied extensively in the past decade or so, culminating in the anticipated FDA approval of the first peanut oral immunotherapy programme in the near future.

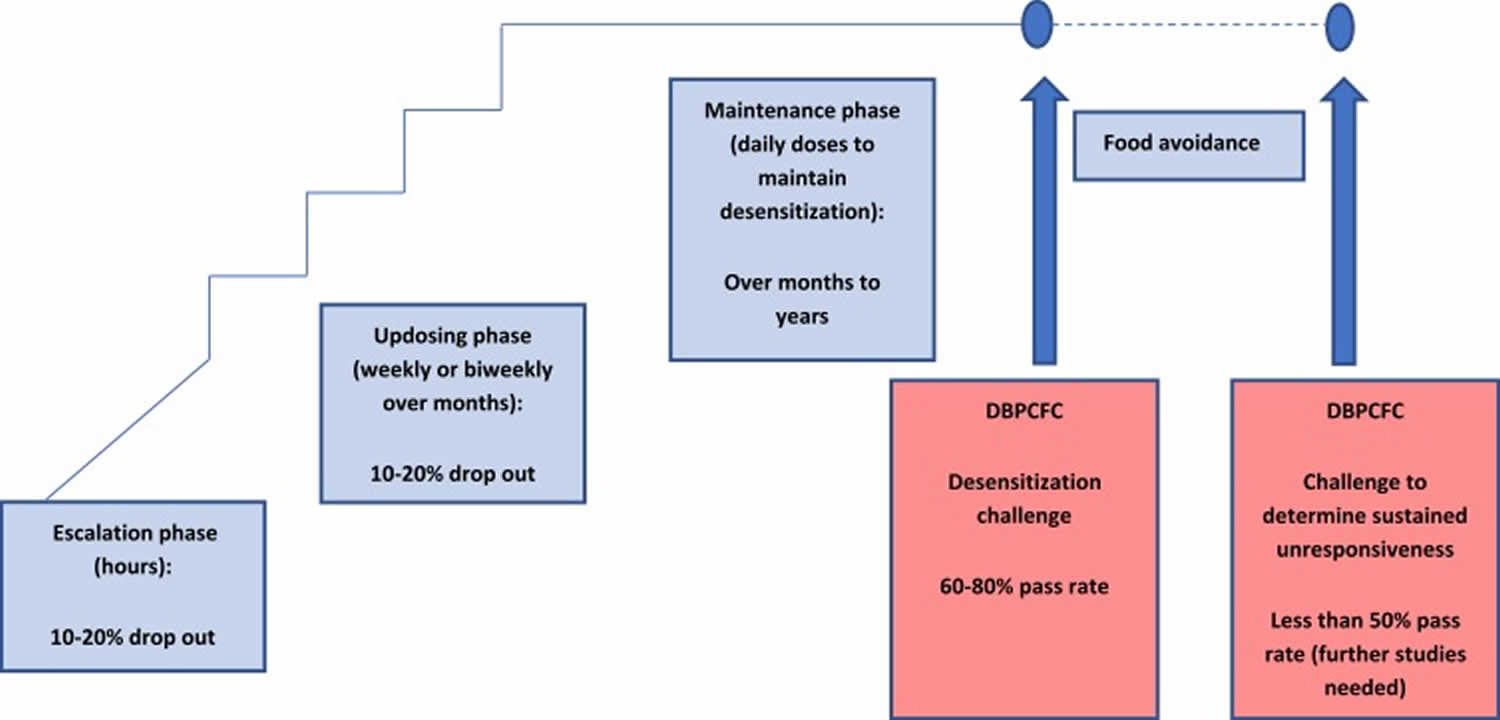

The idea of immunotherapy is initially to raise the threshold of reactivity and protect the patient against small hidden exposure; ultimately permanent resolution of the allergy would be first prize but not routinely achievable 31.

Desensitization is a transient state of reduced reactivity, measured as an increased dose that triggers a reaction in a post-treatment DBPCFC, with the aim of protection from accidental exposure. Interruption of desensitization may lead to the loss of the protective effect.

Sustained unresponsiveness is a more lasting clinical outcome that leaves the treated patient clinically protected for weeks or months, even when not consuming the allergen regularly. This can be measured by intentional interruption of immunotherapy dosing for at least 4–12 weeks followed by a “tolerance” food challenge (see Figure 4) 32. Full tolerance is a permanent resolution of the allergy, with unresponsiveness to the allergen even after prolonged avoidance.

Figure 5. Overview of the peanut oral immunotherapy process

Avoiding foods that contain peanuts

Peanuts are common, and avoiding foods that contain them can be a challenge. The following foods often contain peanuts:

- Ground or mixed nuts

- Baked goods, such as cookies and pastries

- Ice cream and frozen desserts

- Energy bars

- Cereals and granola

- Grain breads

- Marzipan, a candy made of nuts, egg whites and sugar

Less obvious foods may contain peanuts or peanut proteins, either because they were made with them or because they came in contact with them during the manufacturing process. Some examples include:

- Nougat

- Salad dressings

- Chocolate candies, nut butters (such as almond butter) and sunflower seeds

- Ethnic foods including African, Chinese, Indonesian, Mexican, Thai and Vietnamese dishes

- Foods sold in bakeries and ice-cream shops

- Arachis oil, another name for peanut oil

- Pet food

Nut avoidance

The eating or touching of peanuts, peanut butter, peanut flour, arachis oil, and other peanut-containing products must be completely avoided by the patient. Ingredient lists and warnings on manufactured food must be read. Patients need to be particularly careful when eating away from home, where unintended contamination of other foods with peanuts may occur.

It is unclear whether patients with peanut allergy should also avoid all legumes and tree nuts.

- If a specific type of legume or nut has previously been tolerated, it should be safe to continue eating it.

- If the legume or nut has not been tried before, it is safer to assume allergy to it 29.

Be prepared for an allergic reaction

Antihistamines should be carried at all times and taken if an allergic reaction occurs. The patient and their carers should be regularly trained in how to use an adrenaline auto-injector or adrenaline in a prepared syringe, and if the device has to be used, the patient must seek immediate medical attention 29.

If your child has peanut allergy, take these steps to help keep him or her safe:

- Involve caregivers. Ask relatives, babysitters, teachers and other caregivers to help. Teach the adults who spend time with your child how to recognize signs and symptoms of an allergic reaction to peanuts. Emphasize that an allergic reaction can be life-threatening and requires immediate action. Make sure that your child also knows to ask for help right away if he or she has an allergic reaction.

- Use a written plan. List the steps to take in case of an allergic reaction, including the order and doses of all medications to be given, as well as contact information for family members and health care providers. Provide a copy of the plan to family members, teachers and others who care for your child.

- Discourage your child from sharing foods. It’s common for kids to share snacks and treats. However, while playing, your child may forget about food allergies or sensitivities. If your child is allergic to peanuts, encourage him or her not to eat food from others.

- Make sure your child’s epinephrine autoinjector is always available. An injection of epinephrine (adrenaline) can immediately reduce the severity of a potentially life-threatening anaphylactic reaction, but it needs to be given right away. If your child has an emergency epinephrine injector, make sure your family members and other caregivers know about your child’s emergency medication — where it’s located, when it may be needed and how to use it.

- Make sure your child’s school has a food allergy management plan. Guidelines are available to create policies and procedures. Staff should have access to and be trained in using an epinephrine injector.

- Have your child wear a medical alert bracelet or necklace. This will help make sure he or she gets the right treatment if he or she isn’t able to communicate during a severe reaction. The alert will include your child’s name and the type of food allergy he or she has, and may also list brief emergency instructions.

If you have peanut allergy, do the following:

- Always carry your epinephrine autoinjector.

- Wear a medical alert bracelet or necklace.

Test family members for peanut allergy

Between 5% and 9% of siblings of children with a peanut allergy will also have a peanut allergy. In individuals at high risk of an allergic reaction (those with asthma, eczema, or other food allergies) or in cases of parental anxiety, it is advisable to perform skin prick testing or specific IgE testing before the child introduces peanut into their diet. In individuals at low risk of an allergy, peanuts can be carefully introduced to test for an allergic reaction 29.

Oral Immunotherapy (Specific Oral Tolerance Induction)

Over the past decade, hundreds of patients have participated in randomized trials of peanut oral immunotherapy. There has been much heterogeneity between oral immunotherapy trials with different dosing regimens and endpoints, making results difficult to compare and interpret 33.

In an attempt to pool available results, a recently published meta-analysis 34 analyzed 12 clinical trials of peanut oral immunotherapy involving 1041 patients followed up for a median of 12 months; comparing peanut oral immunotherapy versus placebo or peanut avoidance. Oral immunotherapy outperformed no oral immunotherapy on the standard primary endpoint: an estimated 40% of the treatment group passed a supervised oral food challenge at the end of the regular treatment period compared with 3% of the control group. However, many more serious adverse events were observed in the treatment group. There was a pooled prevalence of 22% of the anaphylaxis in oral immunotherapy group, versus 7% in those without active peanut oral immunotherapy (placebo or avoidance). This equated to an additional 15 anaphylactic events per 100 treated patients.

The conclusion of this meta-analysis 34 is that there is strong evidence that peanut oral immunotherapy results in desensitization, but the process carries a significant risk, albeit a “controlled risk” to a large degree.

The first Phase 3 clinical trial of oral immunotherapy enrolled 554 peanut-allergic patients, aged 4–55 years, with reactivity at a maximum clinical dose of 100 mg peanut protein 35. Patients were randomized in a ratio of active to placebo of 3:1. The primary endpoint was tolerating, with no or mild symptoms, greater than or equal to 600 mg single dose peanut protein in a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (cumulative dose 1043 mg as double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge was done per modified PRACTALL guidelines), conducted 6 months after achieving a 300 mg maintenance dose. Results showed that 67% of the actively treated group tolerated greater than or equal to 600 mg peanut protein at the exit challenge, versus 4% of the placebo group. The incidence of mild-to-moderate adverse events was high in both the active and placebo groups, but serious adverse events were significantly higher in the active group: 4.3% of the active group had a serious adverse event v 0.8% of the placebo group. There was one case of eosinophilic oesophagitis in the active group.

The significant and convincing rate of achieving desensitization at the exit peanut challenge led to FDA consideration for approval of the peanut protein desensitization “drug,” in September 2019 as Palforzia in the USA. The FDA has stipulated that during this treatment, the patient needs to carry an adrenaline autoinjector, and that initial dosing and updosing have to be performed at a facility capable of treating severe allergic reactions.

Sublingual immunotherapy to peanut

Recent studies show that sublingual immunotherapy may be a safe and effective way for peanut allergy sufferers to protect themselves from severe allergic reactions.

Because peanut protein avoids digestion when given sublingually, patients are given far smaller amounts of peanut protein, ranging from 0.0002 mg to 2 mg 36. Sublingual immunotherapy to peanut poses smaller risks of side effects but efficacy remains to be established in larger studies. Kim et al 37 followed 48 patients on a sublingual immunotherapy to peanut programme of 2 mg daily for 5 years; at the oral challenge after 5 years of maintenance, 67% were able to tolerate at least 750 mg of peanut protein without serious side effects, and 25% could tolerate 5000 mg.

Several smaller studies 38 have been published on sublingual immunotherapy to peanut showed a statistically significant increase in rate of desensitization in comparison with placebo. However, with sublingual immunotherapy to peanut the median threshold dose increased approximately 20-fold, in comparison with more than 300-fold with oral immunotherapy, hence oral immunotherapy seems more effective. A major advantage of sublingual immunotherapy to peanut is improved safety profile over oral immunotherapy.

Pharma companies are currently working on a sublingual immunotherapy for possible commercialization.

Epicutaneous immunotherapy

Epicutaneous application of peanut patches that release small amounts of peanut protein via the skin on a daily basis to effect desensitization represents a potentially safe and “easy” form of desensitization. Epicutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy requires application of the patch to intact skin to ensure a tolerogenic effect, thus avoiding the transcutaneous sensitization potential of eczematous skin 39. A patch applied to intact skin leads to solubilization of the allergen and direct uptake by antigen-presenting cells, with transport to lymph nodes without entering the bloodstream.

A published study with a 250-µg epicutaneous peanut patch showed a 25% increase above placebo in the primary endpoint (primary endpoint was a 10-fold increase in the reaction-eliciting dose, or tolerating 1000 mg of peanut protein) 40. In a phase 3 study, 356 peanut-allergic children were randomised 2:1 to receive a daily active patch of 250-µg peanut protein or placebo, for 12 months. In the exit challenge, participants were considered responders if they tolerated at least 100 mg peanut protein (143 mg cumulative) if their entry eliciting dose was 10 mg or less; or at least 300 mg peanut protein (443 mg cumulative) if their entry eliciting dose was >10 mg. Using these criteria, the response rate was 35.3% in active group versus 13.6% in the placebo group 41. Based on this latter study, the pharma company initiating the trials has submitted its “Viaskin” patch for Biologics License Application to the FDA for review.

Baby peanut allergy prognosis

About 20% of children with their allergy will grow out of peanut allergy 42. The allergy persists into adult life in the majority of affected individuals.

References- Food allergy in under 19s: assessment and diagnosis. Clinical guideline [CG116]. Published date: 23 February 2011 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg116

- Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 126: S1–58. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.007

- Pumphrey RS, Gowland MH. Further fatal allergic reactions to food in the United Kingdom, 1999–2006. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 119: 1018–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.021

- Sicherer SH, Forman JA, Noone SA. Use assessment of self-administered epinephrine among food-allergic children and pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2000 Feb;105(2):359-62.

- Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, Jones SM, Sampson HA, Wood RA, Plaut M, Cooper SF, Fenton MJ, Arshad SH, Bahna SL, Beck LA, Byrd-Bredbenner C, Camargo CA, Eichenfield L, Furuta GT, Hanifin JM, Jones C, Kraft M, Levy BD, Lieberman P, Luccioli S, McCall KM, Schneider LC, Simon RA, Simons FE, Teach SJ, Yawn BP, Schwaninger JM., NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Food Allergy in the United States: Summary of the NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel Report. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010 Dec;126(6):1105-18.

- Bublin M, Breiteneder H. Developing therapies for peanut allergy. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2014;165(3):179-94.

- Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Eng J Med. 2015;372:803–813. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1414850

- Skolnick HS, Conover-Walker MK, Barnes C, et al. The natural history of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:367–374. doi:10.1067/mai.2001.112129

- Gray CL, Venter C, Emanuel S, Fleischer D. Peanut introduction and the prevention of peanut allergy: evidence and practical implications. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;31:28–30.

- du Toit G, Sayre PH, Roberts G, et al. Effect of avoidance on peanut allergy after early peanut consumption. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1435–1443. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1514209

- Feeney M, du Toit G, Roberts G, et al. Impact of peanut consumption in the LEAP Study: feasibility, growth, and nutrition. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:1108–1118. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.04.016

- Koplin JJ, Peters RL, Dharmage SC, et al. Understanding the feasibility and implications of implementing early peanut introduction for prevention of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:1131–1141. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.04.011

- Fleischer DM, Sicherer S, Greenhawt M, et al. Consensus communication on early peanut introduction and prevention of peanut allergy in high-risk infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:258–261. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.06.001

- Togias A, Cooper SF, Acebal ML, et al. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:29–44. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.10.010

- Shaker M, Stukus D, Chan ES, Fleischer DM, Spergel JM, Greenhawt M. “To screen or not to screen”: comparing the health and economic benefits of early peanut introduction strategies in five countries. Allergy. 2018;73:1707–1714. doi:10.1111/all.2018.73.issue-8

- Perkin MR, Logan KL, Tseng A, et al. Randomized trial of introduction of allergenic foods in breast-fed infants. N Eng J Med. 2016;374:1733–1743. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1514210

- Perkin MR, Logan KL, Bahnson HT, et al. Efficacy of the Enquiring About Tolerance (EAT) study among infants at high risk of developing food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:1606–1614. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2019.06.045

- Gray CL. Current Controversies and Future Prospects for Peanut Allergy Prevention, Diagnosis and Therapies. J Asthma Allergy. 2020;13:51–66. Published 2020 Jan 16. doi:10.2147/JAA.S196268 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6970608

- ASCIA Guide for introduction of peanut to infants with severe eczema and/or food allergy. https://www.allergy.org.au/health-professionals/papers/ascia-guide-peanut-introduction

- Togias A, Cooper SF, Acebal ML, et al. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: Report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases–sponsored expert panel. The World Allergy Organization Journal. 2017;10(1):1. doi:10.1186/s40413-016-0137-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5217343/

- Turner PJ, Campbell DE. Implementing primary prevention for peanut allergy at a population level. JAMA 2017 Feb 13. www.jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2603418

- Soriano VX, Peters RL, Ponsonby AL, et al. Earlier ingestion of peanut after changes to infant feeding guidelines: the earlyNuts study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:1327–1335. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2019.07.032

- du Toit G, Katz Y, Sasieni P, et al. Early consumption of peanuts in infancy is associated with a low prevalence of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:984–991. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2008.08.039

- Matsumoto K, Mori R, Miyazaki C, Ohya Y, Saito H. Are both early egg introduction and eczema treatment necessary for primary prevention of egg allergy? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:1997–2001. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2018.02.033

- Simpson EL, Chalmers JR, Hanifin JM, et al. Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective atopic dermatitis prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:818–823. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.005

- Lowe AJ, Su JC, Allen KJ, et al. A randomised trial of a barrier lipid replacement strategy for the prevention of atopic dermatitis and allergic sensitisation: the PEBBLES pilot study. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:e19–e21. doi:10.1111/bjd.15747

- Tsilochristou O, du Toit G, Sayre PH, et al. Association of Staphylococcus aureus colonization with food allergy occurs independently of eczema severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:494–503. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2019.04.025

- Al-Muhsen S, Clarke AE, Kagan RS. Peanut allergy: an overview. CMAJ. 2003 May 13;168(10):1279-85.

- Stiefel G, Anagnostou K, Boyle RJ, et al. BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of peanut and tree nut allergy. Clin Exp Allergy 2017; 47: 719–39. DOI: 10.1111/cea.12957

- Soares-Weiser K, Takwoingi Y, Panesar SS, et al. The diagnosis of food allergy: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2014;69:76–86. doi:10.1111/all.12333

- Anna Nowak-Węgrzyn A, Albin E. Oral immunotherapy for food allergy. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;29(2):90–99.

- Vickery BP, Scurlock AM, Kulis M, et al. Sustained unresponsiveness to peanut in subjects who have completed peanut oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:468–475. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.007

- Yee CS, Rachid R. The heterogeneity of oral immunotherapy clinical trials: implications and future directions. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016;16:25. doi:10.1007/s11882-016-0602-0

- Chu DK, Wood RA, French A, et al. Oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy (PACE): a systemic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and safety. Lancet. 2019;3293(10187):2222–2232.

- Vickery BP, Vereda A, Casale TB, et al.; PALISADE Group of Clinical Investigators. AR101 oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1991–2001.

- Vickery BP, Ebisawa M, Shreffler WG, Wood RA. Current and future treatment of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:357–365. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.11.049

- EH K, Yang L, Ping Y, et al. Long-term sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy in children: clinical and immunological evidence of desensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019. e-published ahead of print.

- Narisety SD, Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA, Keet CA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of sublingual versus oral immunotherapy for the treatment of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1275–1282. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.005

- Mondoulet L, Dioszeghy V, Puteaux E, et al. Intact skin and not stripped skin is crucial for the safety and efficacy of peanut epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT) in mice. Clin Transl Allergy. 2012;2:22. doi:10.1186/2045-7022-2-22

- Sampson HA, Shreffler WG, Yang WH, et al. Effect of varying doses of epicutaneous immunotherapy vs placebo on reaction to peanut protein exposure among patients with peanut sensitivity: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1798–1809. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.16591

- Fleisher DM, Sussman GL, Begin P. Effects of epicutaneous immunotherapy on inducing peanut desensitization in peanut-allergic children: topline Peanut Epicutaneous Immunotherapy Efficacy and Safety (PEPITES) randomized clinical trial results. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:AB410. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.967

- Patel R, Koterba AP. Peanut Allergy. [Updated 2019 Nov 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538526