Pericardial window

Pericardial window is a surgery done on the fibrous sac called the pericardium that surrounds your heart. Pericardial window involves the excision of a portion of the pericardium, which allows the effusion to drain continuously into the peritoneum or chest 1. Pericardial window is used diagnostically and more often, therapeutically for drainage of accumulated pericardial fluid (a condition that most often occurs after cardiac surgery but has many other possible causes) 2. The fluid can be drained in any of 3 ways: via a small subxiphoid incision, thoracoscopically 3 or via a thoracotomy 4.

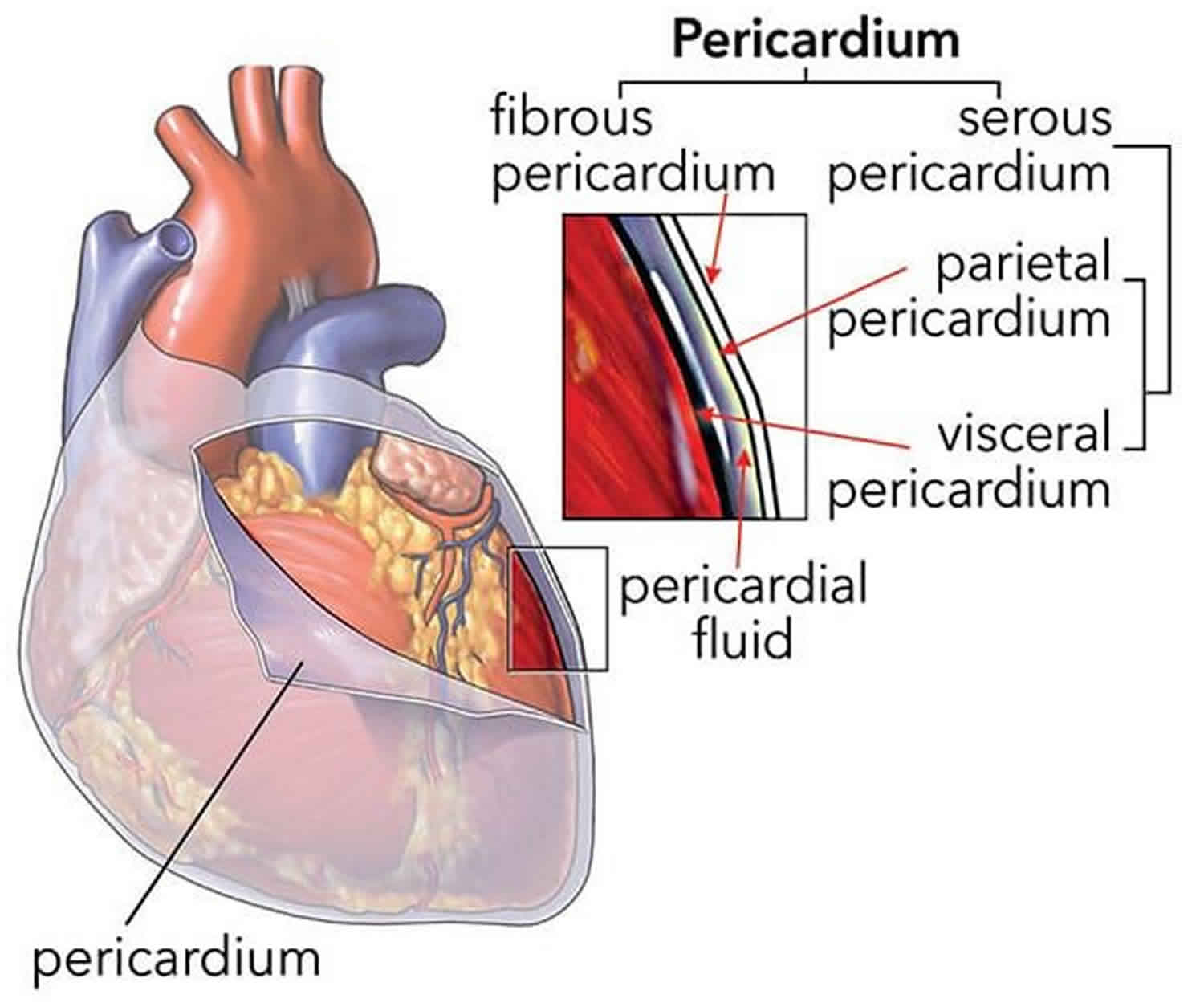

The pericardium envelops the heart like a cocoon and it is a sac that has 2 thin layers with a small amount of fluid in between them. The fluid helps reduce friction between the 2 layers as they rub against each other when the heart beats. In some cases, too much fluid builds up between the layers. This is called a pericardial effusion. When the limited space between the noncompliant pericardium and heart is acutely filled with blood or fluid, cardiac compression and tamponade may result. When this happens, the heart has trouble functioning properly. A pericardial window is one method of draining excess fluid and preventing future fluid buildup. Pericardial window in combination with systemic chemotherapy may also prevent accumulation of large fluid volumes in patients with neoplastic pericardial disease 5.

Doctors can do a pericardial window in a number of ways. In most cases, doctors do the procedure under general anesthesia. In one approach, the surgeon makes a cut under the bottom of the breastbone to get to the pericardium. Or, the surgeon makes a cut between the ribs to reach the pericardium. Doctors may also perform a method that uses several small incisions on the side of the chest. This is called video-assisted thoracoscopy, or VATS. They use small cameras and small tools to create the pericardial window through these small holes.

Pericardial window indications

Many different conditions can cause fluid to build up abnormally around your heart. This can cause shortness of breath, dizziness, nausea, low blood pressure, and chest pain. Sometimes this is treatable with medicines. In other cases, this abnormal fluid is life threatening and requires urgent drainage.

A pericardial window can help decrease the fluid around the heart. It can also help diagnose the cause of the extra fluid.

The following are indications for a pericardial window 6:

- Infection of the heart or pericardial sac

- Cancer

- Inflammation of the pericardial sac due to a heart attack

- Injury

- Immune system disease

- Reactions to certain drugs

- Radiation

- Metabolic causes, like kidney failure with uremia

- Sometimes doctors don’t know why the fluid builds up.

- Symptomatic pericardial effusions

- Asymptomatic pericardial effusions that warrant a pericardial window for diagnosis

- Hemodynamically stable patients with an undiagnosed pericardial effusion (a thoracoscopic approach is ideal)

- Coexisting pericardial, pleural, or pulmonary pathology that requires diagnosis or therapy (a thoracoscopic approach is ideal)

- Known benign effusions that reaccumulate after aspiration

- Drainage of a purulent pericardial effusion

- Early fungal or tuberculous pericarditis in which resection of the pericardium is required to prevent future pericardial constriction

- Use as part of the mediastinal debridement, in patients with descending mediastinitis

- Loculated effusions situated unilaterally or posteriorly (more easily approached thoracoscopically)

- Chylopericardium (thoracoscopic window and ligation of the thoracic duct)

- Delayed hemopericardium or effusions after cardiac surgery (usually treated via a subxiphoid approach, but a thoracoscopic approach is also used)

- An effusion in a patient with a substernal gastric or colonic conduit in whom a subxiphoid approach is not possible (an unusual indication for a thoracoscopic pericardial window)

A pericardial window is not the only way to remove fluid around the heart. Another procedure used by doctors is catheter pericardiocentesis. This uses a needle and a long, thin tube (a catheter) to drain the fluid from the heart. But if your condition makes this method difficult, your doctor is more likely to use a pericardial window. Your doctor might also be more likely to advise surgery if you have had catheter pericardiocentesis in the past and the excess fluid came back. You are also more likely to need surgery if a piece of your pericardium needs to be examined. This is done to diagnose the source of the fluid.

The fluid from the heart can also be drained without a piece of the pericardium being removed. Ask your doctor about which procedure make the most sense for you.

Pericardial window contraindications

The following is a contraindication for a pericardial window 6:

- Concomitant cardiac surgery necessitating a sternotomy for which a full pericardiotomy would be performed

Pericardial window procedure

Pericardial window is usually performed under general anesthesia. Ask your doctor how to prepare for a pericardial window procedure. You should not eat or drink anything after midnight before the day of the surgery. Ask the doctor whether you need to stop taking any medications before the surgery.

The doctor may want some extra tests before the surgery. These might include:

- Chest X-ray

- Electrocardiogram (ECG), to check the heart rhythm

- Blood tests, to assess general health

- Echocardiogram, to view heart anatomy and blood flow through the heart

- Imaging tests such as CT or MRI, if the doctor needs more information about the heart

- Heart catheterization, to measure the pressures within the heart

Any hair around the area of the operation may be removed. About an hour before the operation, you may be given medicines to help you relax.

Talk with the doctor about what to expect during the surgery. The details of your surgery will vary according to the kind of repair the doctor is doing. Usually, doctors do the repair without the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (a heart-lung machine). During the repair, the team will carefully monitor your vital signs. In general:

- An anesthesiologist will probably give you general anesthesia before the surgery starts. You will sleep deeply and painlessly during the operation. You may have a breathing tube put down your throat during surgery to help you breathe. You won’t remember it afterwards.

- In a few cases, doctors might not do the procedure under general anesthesia. If this is the case, the doctor will give you a medicine to make you relax during the procedure. The doctor will also provide numbing medicines at the sites of the incisions.

- The surgery will take several hours.

There are several options for the pericardial window procedure:

- In some cases, the surgeon will make a cut (incision) a few inches below the breastbone, or between the ribs. Tools are used through this incision. If thoracoscopy is used, several smaller incisions on the side of the chest instead. Small cameras and tools are inserted through these small incisions.

- The doctor will surgically remove a small portion of the pericardium, creating a “window.”

- The doctor might place a chest tube between the layers of the pericardium or in the cavity of the lungs, to help drain the fluid.

- A sample of the fluid may be sent to a lab for analysis.

- The muscle and the skin incisions will be closed and a bandage applied.

Subxiphoid pericardial window

A subxiphoid pericardial window is generally indicated for management of symptomatic pericardial effusion 7.

Generally, the patient will have had some type of imaging study, most often an echocardiogram or a computed tomography scan of the chest. It is important to review these studies prior to surgery to get a sense of the size of the effusion and to determine whether the effusion is predominantly anterior or posterior.

In the subxiphoid approach, the surgeon will be accessing the pericardium anteriorly, over the right ventricle. A vertical incision is made from the tip of the breast bone (xiphoid) extending along the midline of the abdomen. The xiphoid is completely removed and the pericardium is held by a hook. The pericardium is incised and a sucker is inserted to remove extra fluid. The incisions are sutured in layers.

Pericardial window anesthesia

A subxiphoid pericardial window procedure can be performed under general anesthesia or under local anesthesia with sedation, depending on the hemodynamic stability of the patient.

If using general anesthesia in a relatively unstable patient, the patient should be prepped and draped prior to induction in case a sudden cardiovascular collapse requires urgent surgical intervention.

Subxiphoid pericardial window procedure

- A small upper midline incision is made over the xiphoid process.

- The linea alba is incised, exposing the preperitoneal fat, but the peritoneal cavity is not entered.

- The xiphoid process is excised with Mayo scissors, a rongeur, or electrocautery.

- The lower sternum is retracted anteriorly with a Richardson retractor. This will expose the cardiophrenic fat pad and not necessarily the pericardium. Use a small sponge stick or Kittner blunt dissector to sweep the overlying fat pad until the glistening pericardium can be visualized.

- If the preoperative imaging study showed a good amount of fluid collection anteriorly, one can safely use a #15 blade to incise the pericardium. The author would not recommend using a #11 blade.

- With drainage, hemodynamic collapse can occur as a result of a diminished preload. It is important to communicate this with anesthesia ahead of time and to administer fluid boluses as necessary.

- Next, grab an edge of the incised pericardium with a tonsil and excise about an inch and a half of tissue to create the window.

- Use a Yankauer suction tube to probe the pericardial sac and suction out any loculated areas.

- Introduce a drain into the pericardial sac. The author’s preference is to use a 10 Fr flat JP drain and to direct it posteriorly.

- Finally, close the incision.

Thoracotomy approach

A small anterior thoracotomy is made in the fourth or fifth intercostal space. The intercostal space (space between ribs) is exposed by making a small incision on the skin along the crease at the bottom of the breast. An inframammary skin incision (6-8 cm long) allows division of the pectoralis muscle to expose the chosen intercostal space. The intercostal space is opened over the superior margin of the rib to allow entry into the pleural cavity. Your doctor places a retractor to separate the tissues and expose the pericardium. The pericardium is cut and the sample of the pleural fluid is collected for examination. The incision is made on the pericardium in front of the phrenic nerve (nerve that starts in the neck and passes down the lung and heart). The adjacent lung is examined and a biopsy is easily performed if indicated. A chest tube is inserted within the pericardium or the pleura and placed on water seal or suction. The fluid is removed using suction and the incision is closed in layers 1.

Thoracoscopic approach

The thoracoscope is introduced in the seventh intercostal space in the midaxillary line or in line with the anterior superior iliac spine on the right 6. On the left, the incision is placed just posterior to this line. The working incision is placed in the posterior axillary line in the fifth intercostal space or, alternatively, peristernally immediately above the pericardium. With the lung collapsed, the phrenic nerve is identified running vertically down along the pericardium; this nerve should be visualized throughout the operation.

On the left, the nerve runs through the middle of the lateral surface of the pericardium and should be sharply mobilized off the pericardium to allow tension-free retraction and wider access to the pericardial surface. Alternatively, the pericardium may be divided anterior and posterior to the phrenic nerve, so that it is left on an island of pericardium. This is done when a left-side pericardiectomy is to be performed.

On the right, the phrenic nerve is just anterior to the hilum of the lung and does not interfere with pericardial resection. If the posterior pericardium is to be incised, the pulmonary ligament is mobilized with an electrocautery after the lower lobe is grasped and retracted superiorly. This allows greater exposure of the pericardium and allows the lower lobe to be retracted out of the operative field.

If the posterior pericardial space is to be accessed, the posterior mediastinal pleura is opened from the level of the inferior pulmonary vein to the mainstem bronchus. On the right, the esophagus must be mobilized to improve the exposure. Blunt dissection with a tonsil sponge stick allows the pericardium to be separated from the surrounding soft tissue.

Alternatively, the anterior pericardium may incised, which makes these steps unnecessary. Often, the pericardium is distended or thickened, and the easiest approach is to grasp it with a long Allis clamp or ring forceps introduced through the working incision at a point anterior to where the initial incision is to be made, then retract it anteriorly or laterally to tent the pericardium. If the pericardium is too distended to allow this, the effusion is aspirated via a spinal needle introduced through the chest wall under thoracoscopic vision.

A scissors or electrocautery is used to open the pericardium. If the pericardium is very thickened or vascular, an endoscopic gastrointestinal anastomosis (GIA) vascular stapler can be used to extend the incision after the initial pericardial opening is made.

Adhesions between the heart and the pericardium may be dissected sharply with scissors or bluntly with a peanut dissector or Yankauer sucker, depending on the density or tenacity of the adhesion. The substernal plane can be dissected with an electrocautery across the midline or to the contralateral chest, depending on the size of the window to be created and on whether a pericardiectomy is to be performed. The opening in the pericardium should be a minimum of about 4 × 4 cm to ensure that the pericardial space will be adequately drained.

Once the window has been created, a Yankauer sucker is used to probe the pericardial space so as to ensure complete drainage of the effusion and break down fibrous septa that may prevent complete drainage. A 28-French chest tube or a No. 19 Blake drain is placed in the pericardiopleural or pleural space and brought out through the camera port incision 6.

Pericardial window complications

As with other diagnostic and treatment procedures, pericardial window may be associated with certain complications, including:

- Excess bleeding

- Infection

- Blood clot (which can lead to stroke or other problems)

- Abnormal heart rhythms or arrhythmias (which can cause death in rare instances)

- Cardiac arrest

- Heart attack

- Complications from anesthesia

- Return of pericardial effusion, requiring reoperation

- Need for a repeat procedure

- Damage to the heart

There is also a chance that the fluid around the heart will come back. If this happens, you might need to repeat the procedure, or you might eventually need the whole pericardium removed.

Your own risks may vary according to your age, your general health, and the reason for your procedure or type of surgery you have. They may also vary depending on the anatomy of the heart, fluid, and pericardium. Talk with your healthcare provider to find out what risks may apply to you.

Pericardial window recovery

Ask your doctor about what to expect after the procedure. In general, after your pericardial window:

- You may be groggy and disoriented upon waking.

- Your vital signs, such as your heart rate, breathing, blood pressure, and oxygen levels, will be closely monitored.

- You will probably have a tube draining the fluid from your heart or chest.

- You may feel some soreness, but you shouldn’t feel severe pain. Pain medicines are available if needed.

- You will probably be able to drink the day after surgery. You can have regular foods as soon as you can tolerate them.

- You will probably need to stay in the hospital for at least a few days. This will partially depend on the reason you needed a pericardial window.

After you leave the hospital:

- You will have your stitches or staples removed in a follow-up appointment in 7 to 10 days. Be sure to keep all follow-up appointments.

- You should be able to resume normal activities relatively soon, but you may be a little more tired for a while after the surgery.

- Ask your doctor if you have any exercise limitations. Avoid heavy lifting.

- Call your doctor if you have fever, increased draining from the wound, increased chest pain, or any severe symptoms.

- Follow all the instructions your healthcare provider gives you for medicines, exercise, diet, and wound care.

Many people note improvements in their symptoms right after having a pericardial window done.

References- Liberman M, Labos C, Sampalis JS, Sheiner NM, Mulder DS. Ten-year surgical experience with nontraumatic pericardial effusions: a comparison between the subxyphoid and transthoracic approaches to pericardial window. Arch Surg. 2005 Feb. 140(2):191-5.

- Pericardial Window. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1829679-overview

- Muhammad MI. The pericardial window: is a video-assisted thoracoscopy approach better than a surgical approach?. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011 Feb. 12(2):174-8.

- Mangi AA, Torchiana DF. Pericardial disease. Cohn LH. Cardiac Surgery in the Adult. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. 1465-1478.

- Lestuzzi C, Berretta M, Tomkowski W. 2015 update on the diagnosis and management of neoplastic pericardial disease. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2015 Apr. 13(4):377-89.

- Thoracoscopic Pericardial Window. https://www.ctsnet.org/article/thoracoscopic-pericardial-window

- Gwan-Nulla D. Subxiphoid Pericardial Window: Steps and Helpful Tips. February 2019. doi:10.25373/ctsnet.7663130