Positional plagiocephaly

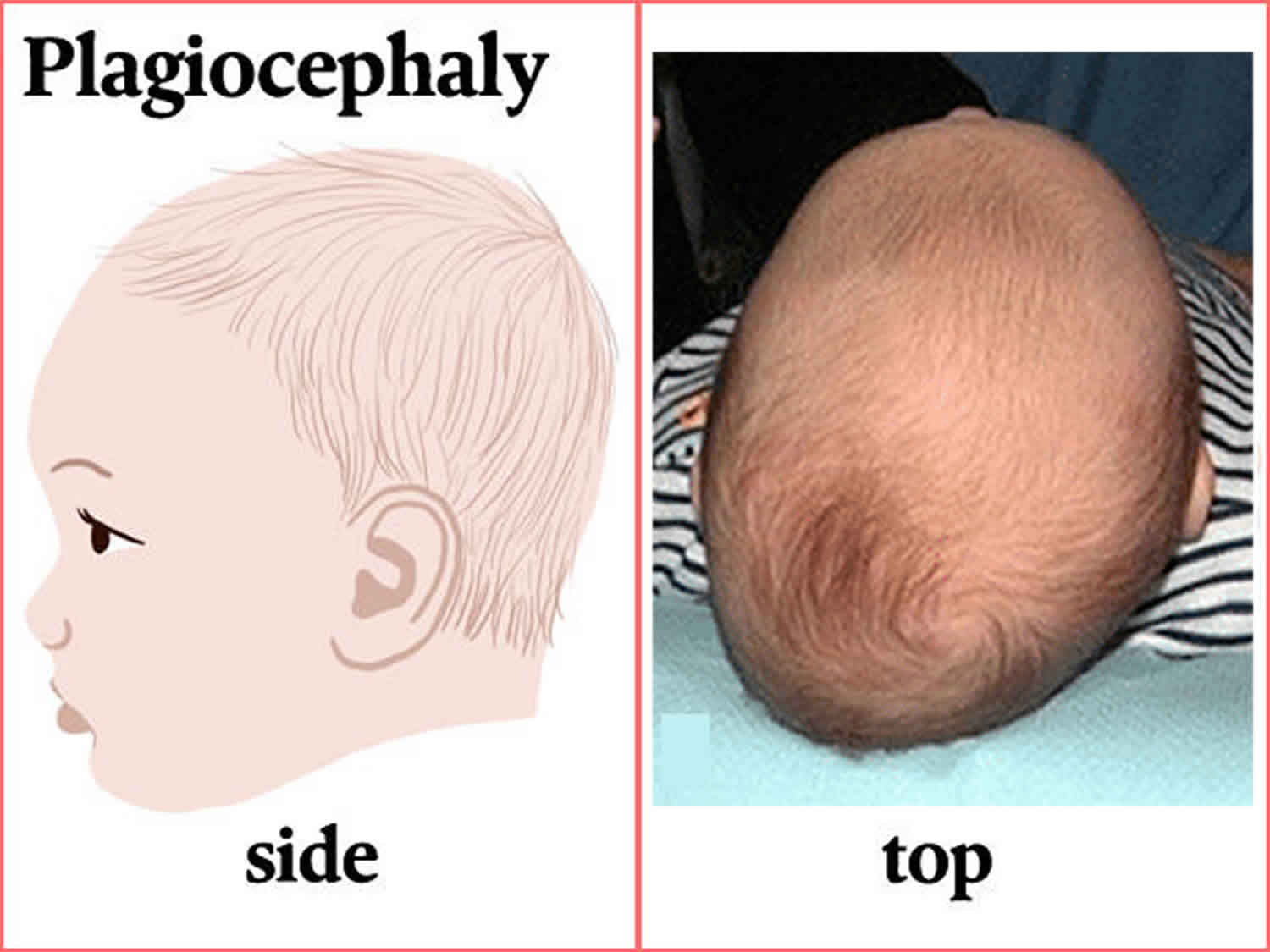

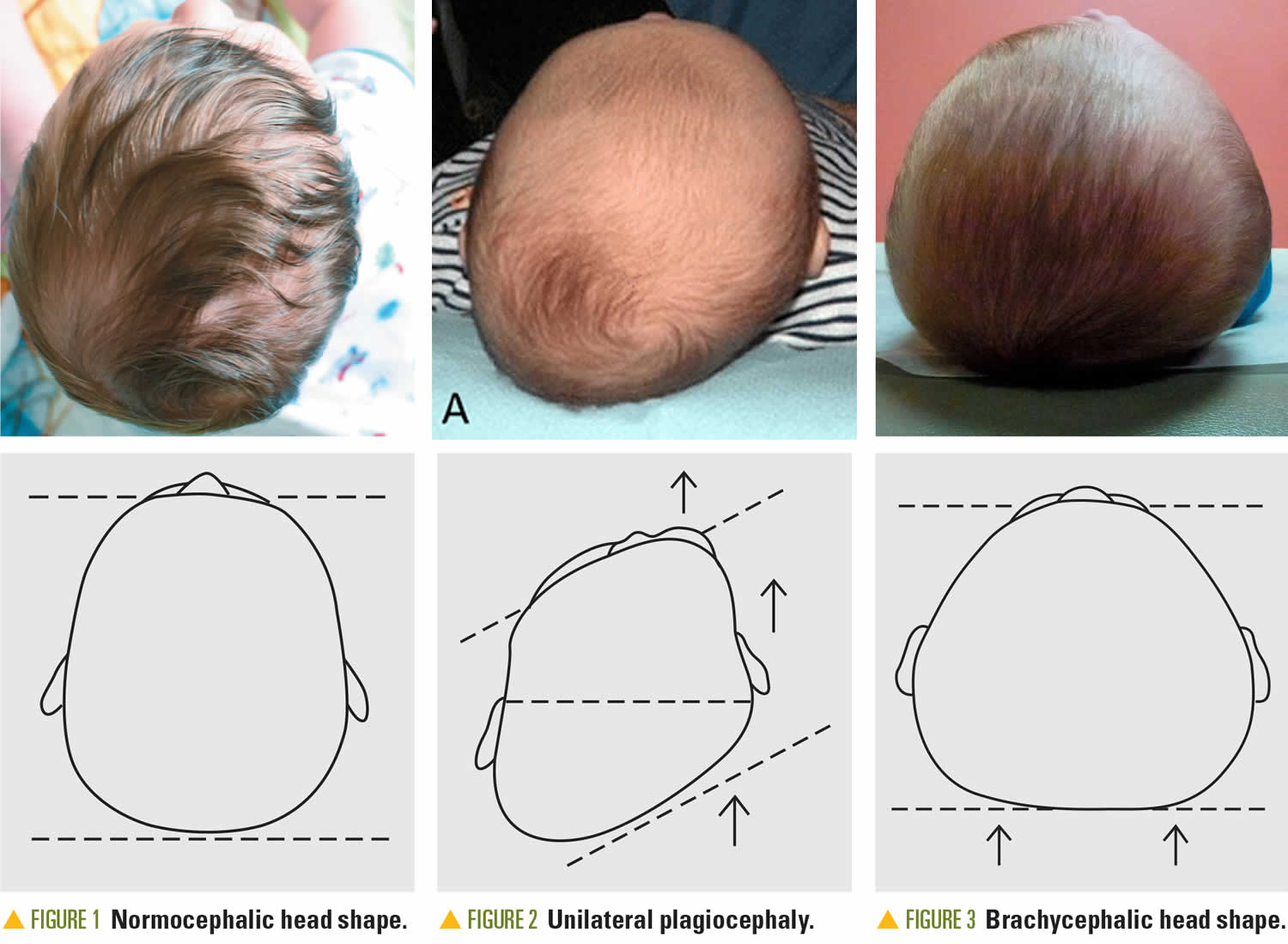

Plagiocephaly literally means “oblique head” from the Greek word “plagio” for oblique and “cephale” for head and corresponds to a flat head (unilateral or bilateral occipital flattening), which may arise due to the continual influence of external forces on the immature skull (nonsynostotic posterior plagiocephaly) or because of premature fusion of one or both lambdoid sutures (synostotic posterior plagiocephaly) 1. Anterior plagiocephaly can be used to define the cranial deformation characterized by premature unilateral fusion of the coronal suture.

Positional plagiocephaly also called flattened head syndrome or deformational plagiocephaly is the most common cause of plagiocephaly (prevalence of 5-48% in healthy newborn infants) 2 versus an incidence of 0.003% of synostotic plagiocephaly (lamboid synostosis) 3.

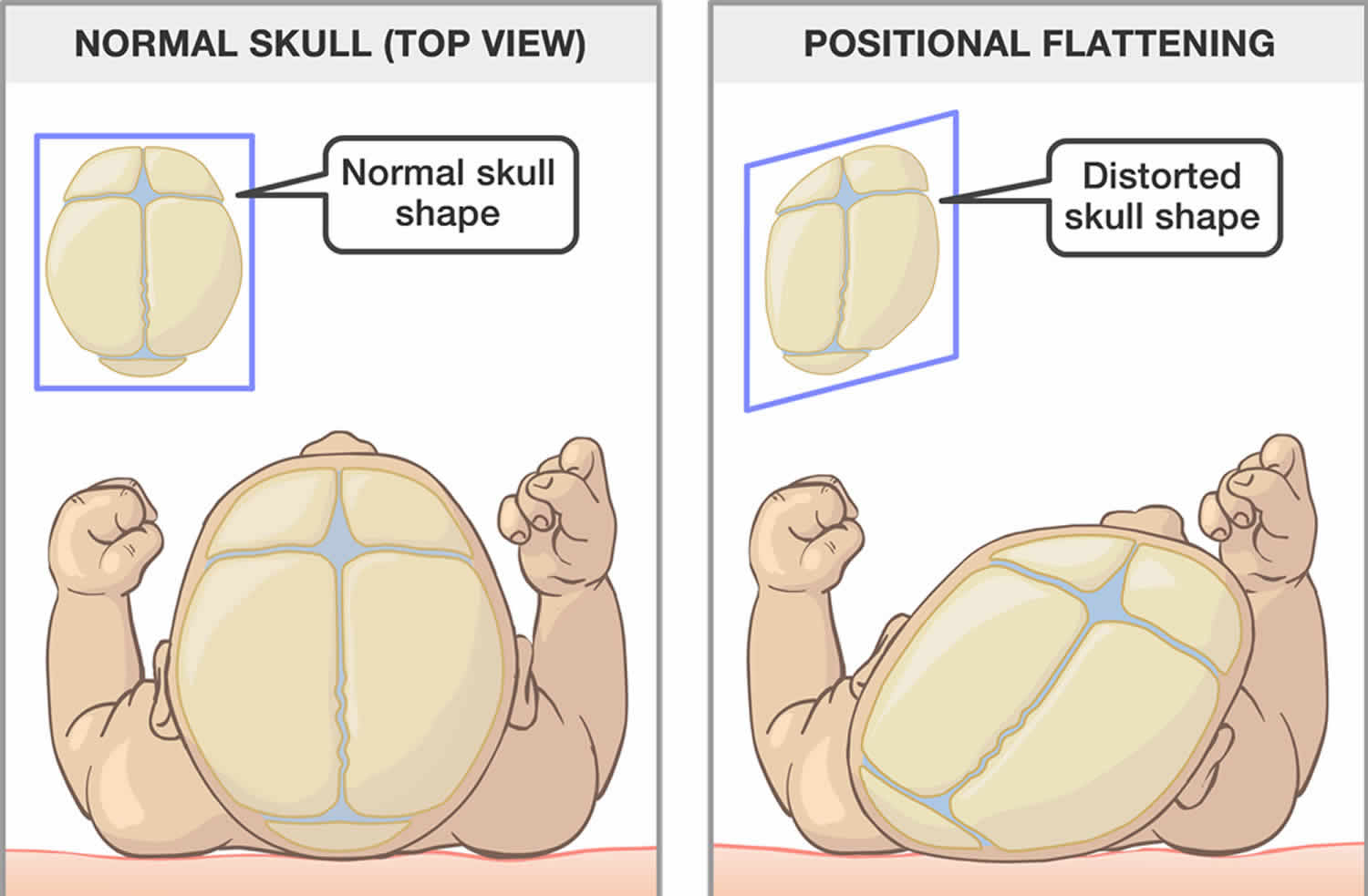

Positional plagiocephaly is also called non-synostotic plagiocephaly or deformational plagiocephaly, refers to a flattened, misshapen or asymmetrical (uneven) head shape caused by repeated pressure to the same area of the skull. There is another type of plagiocephaly caused by abnormal closure of the skull bones. This is called synostotic plagiocephaly or craniosynostosis, and is not addressed in this post. When the head has a flat spot at the back of the skull, this is called brachycephaly. Positional plagiocephaly does not affect the development of a baby’s brain, but if left untreated it may change their physical appearance by causing uneven growth of their face and head.

Non-synostotic plagiocephaly falls into three main groups 4:

- Plagiocephaly – skewed occipital flattening,

- Brachycephaly – symmetric occipital flattening, and

- Combined plagiocephaly/brachycephaly.

Positional plagiocephaly or deformational plagiocephaly occurs because the bones of a newborn baby’s head are thin and flexible, so the head is soft and may change shape easily. Flattening of the head in one area may happen if a baby lies with their head in the same position for a long time 5. The incidence of positional plagiocephaly has increased with the start of ‘Back to Sleep’ campaign by the American Academy of Pediatrics 6 and ranges from 1 in 300 live births to 22.1 percent 7. Positional plagiocephaly or deformational plagiocephaly results from an ongoing action of gravitational forces on the occipital region, causing a flattened region of the posterior craniofacial skeleton. If no intervention is performed, the deformity can continue and, in severe cases, evolve with facial deformities. Positional plagiocephaly occurs more often on the right side (70% of cases) and affects more males. The major risk factors include: torticollis, prematurity, multiparity, and a fixed sleeping position.

Deformational plagiocephaly is very common, and can typically be diagnosed with a thorough physical evaluation by a clinician who specializes in treating craniofacial differences. Because positional plagiocephaly can be confused with craniosynostosis, especially unilateral lambdoid synostosis and unicoronal synostosis, accurate diagnosis by an experienced team is extremely important to managing your child’s condition.

Craniofacial experts will be able to differentiate readily between these conditions. In rare cases, your child’s medical team may use a CT scan to confirm the diagnosis and further evaluate your child’s condition. It is important that cases of craniosynostosis be identified early, as these conditions often require surgical treatment, and if left untreated, may result in elevated intracranial pressure.

Most babies with deformational plagiocephaly do not need any treatment at all, especially if they are active and you have plenty of one-on-one interaction with them. Positional plagiocephaly usually improves naturally as your baby grows and gains head control and can move their head by themselves. The plagiocephaly will get better if you encourage your baby to turn their head themselves when they are awake. From the age of two weeks, while you are supporting their head in your hands, your baby can slowly follow your eyes or voice around, even if one way seems harder at first.

If you have concerns about your baby’s head shape or if you notice that your baby only turns their head to one side when lying on their back, see your doctor.

If treatment is necessary, you may be referred to a specialist clinic where your baby will be treated by a team that may include a pediatrician, plastic surgeon, physiotherapist and orthotist.

The most common treatment is provided by the physiotherapist who will encourage active movement, and teach parents how to position their baby and do exercises with them to help improve the head shape.

Deformational plagiocephaly can be associated with torticollis. Torticollis literally means “a tight neck” and can be seen when there are structural anomalies such as fused or hemivertebrae, or most commonly as a completely isolated anomaly.

In the majority of cases, physical therapy to straighten and stretch the neck will straighten the head and head posture. If your child has torticollis, he may habitually sleep in one position and develop plagiocephaly. Treating the torticollis will often help to improve the plagiocephaly as your child is able to sleep more comfortably in different positions. Otherwise, helmet therapy is used.

A very small number of babies with plagiocephaly (less than one in 10) have a severe and persistent deformity, and they may need to be treated with helmet therapy.

If repositioning is not successful in addressing the problem, or if the deformation is moderate or severe and persists beyond six months, then helmet therapy may be required.

Helmet therapy works by fitting the skull tightly with a specially designed helmet in all areas except where it is flat. Leaving extra room around the flat area of the head allows the skull and brain to grow back into the normal shape that they were genetically programmed to do.

Deformational plagiocephaly key points to remember:

- Lie your baby on their back for sleep and do not use pillows in the crib.

- Vary the position of your baby’s head when putting them down to sleep, and your baby’s position when they are awake and alert. Give your baby face time and tummy time.

- Talk to your doctor if you are worried about your baby’s head shape.

- Plagiocephaly usually improves over time if your baby is active and has lots of one-on-one interaction.

- If helmet therapy is needed, it won’t hurt your baby and the outcomes are normally very good.

Figure 1. Positional plagiocephaly

Figure 2. Plagiocephaly and brachycephaly

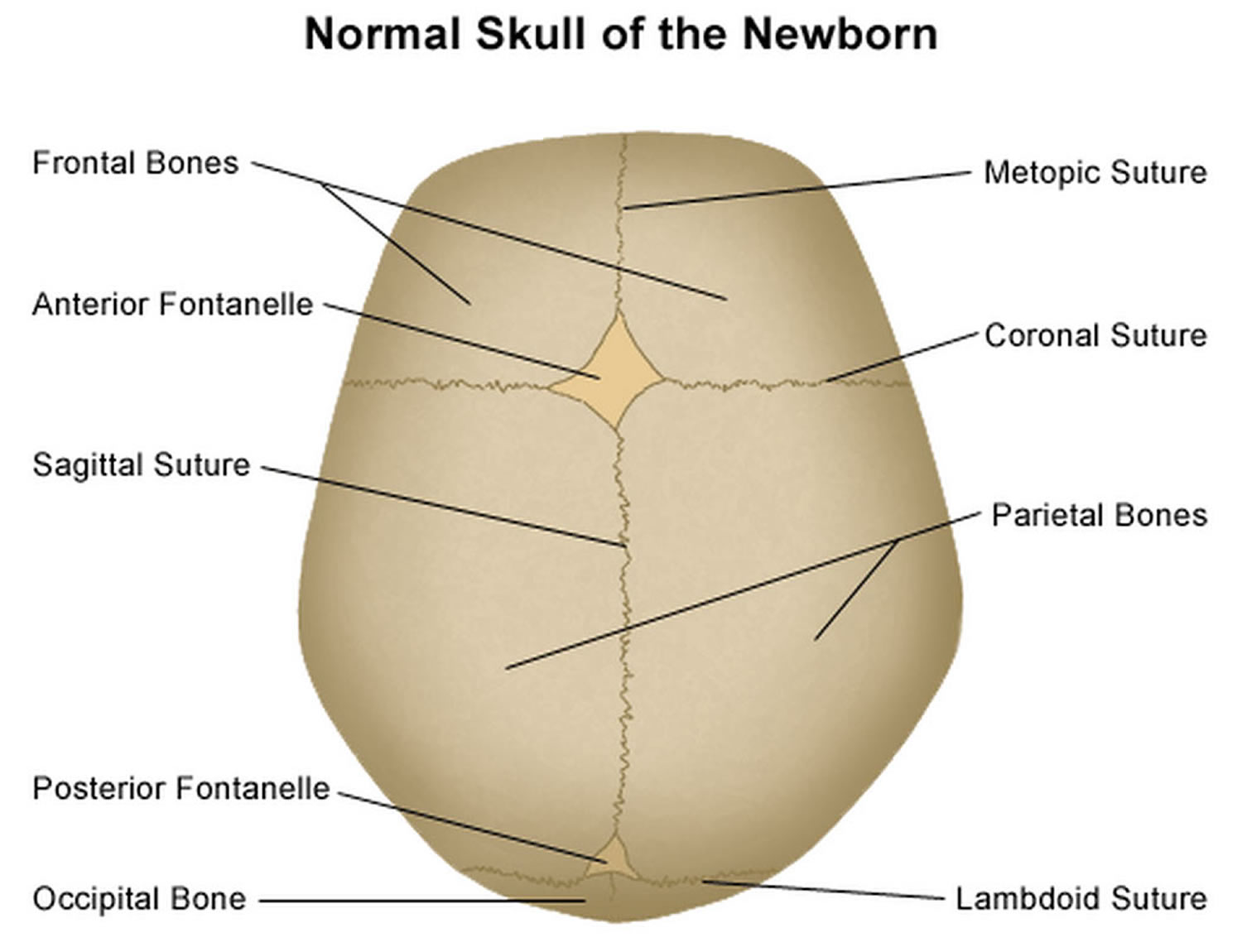

Figure 3. Normal skull of a newborn

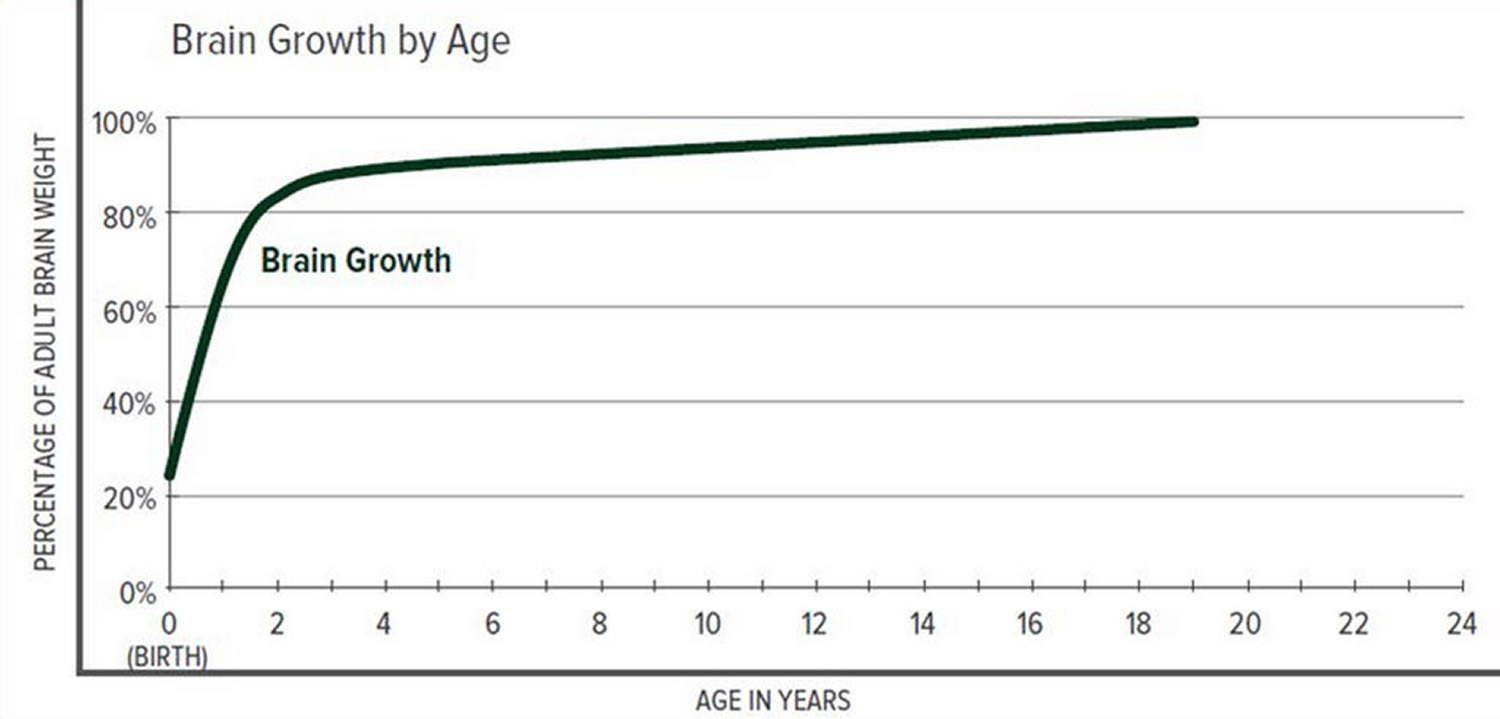

Figure 4. Brain size versus age diagram

What is craniosynostosis?

Craniosynostosis is a birth defect of the skull characterized by the premature closure of one or more of the cranial sutures or fibrous joints between the bones of the skull (joints between the bone plates) before brain growth is complete 8. The occurrence is approximately one for 2000 to 2500 live births 9. The premature fusion of sutures prevents perpendicular growth of the skull, and an increase in brain volume leads to a compensatory growth of the skull parallel to this. Closure of a single suture is most common. Normally the skull expands uniformly to accommodate the growth of the brain and most cranial sutures fuse when a person is 20-30 years of age, with the exception being the metopic suture fusing around 6 months to 2 years; premature closure of a single suture restricts the growth in that part of the skull and promotes growth in other parts of the skull where sutures remain open. This results in a misshapen skull but does not prevent the brain from expanding to a normal volume. However, when many sutures close prematurely, the skull cannot expand to accommodate the growing brain, which leads to increased pressure within the skull and impaired development of the brain. Theoretically, a person can suffer consequences of an early skull suture fusion no matter what age it fuses. However, doctors usually see the most severe consequences when the fusion happens early in life, often before birth.

Craniosynostosis usually involves fusion of a single cranial suture, but can involve more than one of the sutures in your baby’s skull (complex craniosynostosis). In rare cases, craniosynostosis is caused by certain genetic syndromes (syndromic craniosynostosis).

Types of craniosynostosis are:

- Sagittal synostosis (scaphocephaly) is the most common type. It affects the main suture on the very top of the head. The early closing forces the head to grow long and narrow, instead of wide. Babies with this type tend to have a broad forehead. It is more common in boys than girls.

- Frontal plagiocephaly is the next most common type. It affects the suture that runs from ear to ear on the top of the head. It is more common in girls.

- Metopic synostosis is a rare form that affects the suture close to the forehead. The child’s head shape may be described as trigonocephaly. It may range from mild to severe.

Craniosynostosis can be gene-linked or caused by metabolic diseases (such as rickets or vitamin D deficiency) or an overactive thyroid. Some cases are associated with other disorders such as microcephaly (abnormally small head) and hydrocephalus (excessive accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain). The first sign of craniosynostosis is an abnormally shaped skull. Other features can include signs of increased intracranial pressure, developmental delays, or impaired cognitive development, which are caused by constriction of the growing brain. Seizures and blindness may also occur.

Primary craniosynostosis affects individuals of all races and ethnicities and is usually present at birth. Most forms of primary craniosynostosis affect men and women in equal numbers (although males outnumber females 2:1 for sagittal synostosis). Primary craniosynostosis affects approximately 0.6 in 100,000 people in the general population. Overall, craniosynostosis affects approximately 1 in 2,000-2,500 people in the general population. Approximately 80-90 percent of individuals with primary craniosynostosis have isolated defects. The remaining cases of primary craniosynostosis occur as part of a larger syndrome. More than 150 different syndromes have been identified that are potentially associated with craniosynostosis.

In most cases of primary craniosynostosis, affected children usually have normal intelligence and do not have other abnormalities besides the skull malformation. However, when multiple sutures are affected, the skull may be unable to expand enough to accommodate the growing brain. If left untreated, this can cause increased pressure within the skull (intracranial pressure) and can potentially result in cognitive impairment or developmental delays. Increased pressure within the skull can also cause vomiting, headaches, and decreased appetite. In some rare cases, additional symptoms can develop including seizures, misalignment of the spine, or eye abnormalities.

Treatment for craniosynostosis generally consists of surgery to improve the symmetry and appearance of the head and to relieve pressure on the brain and the cranial nerves. For some children with less severe problems, cranial molds can reshape the skull to accommodate brain growth and improve the appearance of the head.

Although neurological damage can occur in severe cases, most children have normal cognitive development and achieve good cosmetic results after surgery. Early diagnosis and treatment are key.

In this context, patients with craniosynostosis not surgically-treated can develop several complications such as 10: Intracranial hypertension occurs in up to 60% of children with complex craniosynostosis and 20% of carriers of simple craniosynostosis; cognitive and developmental disorders, poor weight gain, visual, hearing, and language disorders; and psychological problems such as low self-esteem and social isolation. Therefore, the objective of surgical treatment is to prevent intracranial hypertension and to correct craniofacial abnormalities. Overall, the optimal timing of surgical correction in most cases is between 6 and 9 months of age. The motivations for performing the surgery before 1 year of age include the ability of the child younger than 1 year to completely reossify, the malleable character of the calvaria during this age, and the tremendous brain growth that occurs during the first year, which allows good remodeling of the skull 11. Satisfactory craniofacial form and esthetic pleasing outcomes have also been associated with craniofacial surgical interventions performed before 1 year of age 12. It is noteworthy that the presence of intracranial hypertension signs (irritability, swelling of the papilla, bulging fontanelle, and imaging findings) may result in the need for earlier surgical intervention, to perform decompression procedures or ventricular shunt surgery if associated with hydrocephalus.

Plagiocephaly causes

Positional plagiocephaly or deformational plagiocephaly is acquired cranial asymmetry resulting from physical forces applied over a time, and refers to altered cranial shape in infants older than six weeks of age, when molding from the birth process is over 13. The most commonly reported risk factors are: first-born, male, limited neck rotation or preference in head position, supine sleep position, lower level of activity, and lack of tummy time 14. An increase in prevalence of deformational plagiocephaly was noted in American tertiary centers the 1990s, and this was largely attributed to parents following the recommendation to place their infant supine while sleeping in order to prevent sudden infant death (SIDS) 15. In a prospective cohort study from 2014, 47% of 440 healthy full-term infants seven to 12 weeks of age in Calgary were estimated to have deformational plagiocephaly 16. In a prospective cohort study investigating the natural course, the prevalence of deformational plagiocephaly increased to four months, and the majority of cases reversed by two years of age 17. Although deformational plagiocephaly might disappear as a child grows older and increased mobility relieves pressure on the cranium, it persists in some children. In a study of 129 children diagnosed with deformational plagiocephaly in infancy and whose parents had been given information on counter-positioning strategies, 39% had not reverted to the normal range of symmetry at mean age of four years 18.

Plagiocephaly prevention

A baby’s head position needs to be varied during sleep and when they are awake to avoid them developing deformational plagiocephaly.

- Sleeping position: Your baby must always be placed on their back to sleep to reduce the risk of SIDS (Sudden Infant Death Syndrome or Cot Death). Do not use pillows in the cot for positioning.

- Head and crib position for sleep: A young baby will generally stay in the position they are placed for sleep, until they can move themselves. Alternate your baby’s head position when they sleep. Place your baby at alternate ends of the crib to sleep, or change the position of the crib in the room. Babies often like to look at fixed objects like windows or wall murals, so changing their crib position will encourage them to look at things that interest them from different angles.

- Play time: When your baby is awake and alert, play or interact with them facing you (face time) or place them lying down on their front (tummy time) or on their side from as early as one or two weeks of age. Place rattles or toys (or other people’s faces) that your baby likes to look at in different positions to encourage your baby to turn their head both ways. Even at two weeks of age your baby can follow your voice or eyes (maintain eye contact) and turn their head themselves each way if you support their head in your hands while they are awake and alert.

- Vary your holding and carrying positions of your baby: Avoid having your baby lying down too much by varying their position throughout the day, e.g. use a sling, hold them upright for cuddles, carry them over your arm on their tummy or side.

Plagiocephaly symptoms

It is quite common for a newborn baby to have an unusually shaped head. This can be either related to their position in the uterus during pregnancy, or caused by moulding (changing shape) during labour, including changes caused by instruments used during delivery. Depending on the cause of the unusual shape, most babies’ heads should go back to a normal shape within about six weeks after birth.

Sometimes a baby’s head does not return to a normal shape, or they may have developed a flattened spot at the back or side of their head. Sometimes a flat spot develops when a baby has limited neck movement and prefers resting their head in one particular position.

Plagiocephaly diagnosis

Diagnosis of positional plagiocephaly is eminently clinical and can typically be diagnosed with a thorough physical evaluation by a clinician who specializes in treating craniofacial differences. Because deformational plagiocephaly can be confused with craniosynostosis, especially unilateral lambdoid synostosis and unicoronal synostosis (unilateral fusion of the lambdoid or coronal sutures), accurate diagnosis by an experienced team is extremely important to managing your child’s condition 3. Medical history and physical examination are sufficient to establish the differential diagnosis between a positional plagiocephaly and craniosynostosis in the vast majority of cases (Table 1). Classically, patients with premature fusion of the lambdoid suture already have the deformity at birth, while those with a positional deformity have a normal skull at birth and develop the deformity in the subsequent weeks or months. When asked, parents may mention that there is a preferred position of the baby’s positioning in patients with positional plagiocephaly, while in patients with synostotic plagiocephaly, there is no preferred position.

Medical history

The key questions to differentiate the craniosynostoses from the positional plagiocephaly are 19:

- “Is deformity present at birth?” Craniosynostosis is present at birth, whereas deformational plagiocephaly develops in the neonatal period;

- Is there a preferred sleep position?;

- “Is there improvement of the deformity?” Craniosynostosis gets worse with time, whereas the deformational plagiocephaly improves as the child develops head control and the skull no longer has localized pressure for long periods”.

Table 1. Important characteristics to differentiate between positional plagiocephaly versus lamboid synostosis (craniosynostosis)

Physical examination

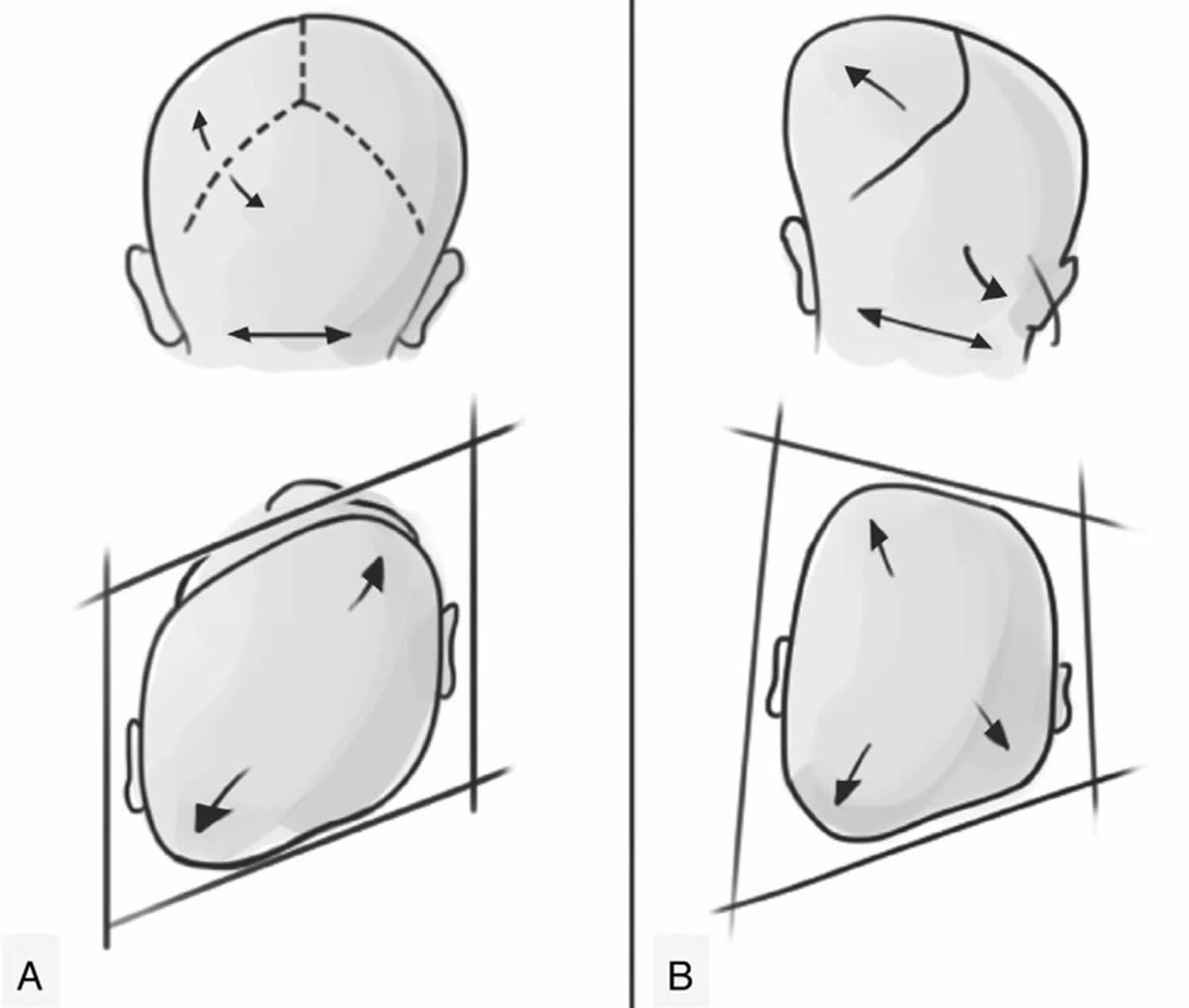

During the physical examination, symmetries between the skull, forehead, and ears should be carefully analyzed. Positional plagiocephaly presents a format of a parallelogram skull, while synostotic posterior plagiocephaly has the shape of a trapezoid 20. Still, an ipsilateral bulging in the mastoid region and a ridge on the fused lambdoid suture can be seen and palpated. In moderate to severe cases in both deformities, compensatory frontal bossing can be observed, ipsilateral in positional plagiocephaly and contralateral in synostotic plagiocephaly. This involvement of the forehead may progress, leading to a facial scoliosis in both pathologies, changing the facial symmetry. In patients with lambdoid suture craniosynostosis, the ipsilateral ear stenosis tends to be in a posterior position and downwards, as if the suture pulled it. While the positional plagiocephaly tends to be in an anterior position, as if it had been pushed (Figure 4). The physical examination should also include evaluation of the cervical region and look for evidence of congenital torticollis and/or thickening of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which are directly related to positional plagiocephaly.

Figure 5. Positional plagiocephaly

Footnote: Representation of positional plagiocephaly and true (synostotic) posterior plagiocephaly. (A) Positional plagiocephaly showing: absence of lambdoid suture stenosis, format of a parallelogram skull, ipsilateral compensatory frontal bossing, ipsilateral ear in an anterior position, as if it had been pushed. (B) True posterior plagiocephaly showing: presence of lambdoid suture stenosis, shape of a trapezoid, ipsilateral bulging in the mastoid region, contralateral compensatory frontal bossing, ipsilateral ear stenosis tends to be in a posterior position and downwards, as if the suture pulled it.

Imaging studies

In rare and difficult cases, when the examination and history are not diagnostic, a good-quality four-view radiographic series (anteroposterior, Towne and two lateral projections) might be sufficient to exclude craniosynostosis and avoid further radiation exposure 21. If it is unclear, because of the very young age of the patient, it is recommended to repeat X-skull after 1 or 2 months 22. CT is not the recommended modality for screening because of the associated radiation exposure and high imaging costs and diagnostics by pediatricians with CT is associated with further delay in referral 22.

After the clinical suspicion (or confirmation) of craniosynostosis, the children should be referred to a multidisciplinary team specialized in craniofacial anomalies (anesthesiologist, plastic surgeon, speech therapist, neurosurgeon, orthodontist, otorhinolaryngologist, and psychologist) 23. In these centers, the radiological exam of choice is the three-dimensional CT scan that contributes to elucidation of the extension of suture fusion and the consequent craniofacial deformity and subsequent surgical planning. It is noteworthy that the cephalic perimeter generally does not change due to compensatory growth of other bones in the majority of cases with simple craniosynostosis.

Plagiocephaly treatment

In most babies with deformational plagiocephaly due to sleeping position, simple repositioning of the child to place them off the flattened area will resolve the problem. The shape of your baby’s head should improve naturally over time as their skull develops and they start moving their head, rolling around and crawling.

To take pressure off the flattened part of your baby’s head:

- give your baby time on their tummy during the day – encourage them to try new positions during play time, but make sure they always sleep on their back as this is safest for them

- switch your baby between a sloping chair, a sling and a flat surface – this ensures there isn’t constant pressure on 1 part of their head

- change the position of toys and mobiles in their cot – this will encourage your baby to turn their head on to the non-flattened side

- alternate the side you hold your baby when feeding and carrying

- reduce the time your baby spends lying on a firm flat surface, such as car seats and prams – try using a sling or front carrier when practical

If treatment is necessary, you may be referred to a specialist clinic where your baby will be treated by a team that may include a pediatrician, plastic surgeon, physiotherapist and orthotist.

If your baby has difficulty turning their head, physiotherapy may help loosen and strengthen their neck muscles. The most common treatment is provided by the physiotherapist who will encourage active movement, and teach parents how to position their baby and do exercises with them to help improve the head shape.

A very small number of babies with deformational plagiocephaly (less than one in 10) have a severe and persistent deformity, and they may need to be treated with helmet therapy.

Corrective surgery may be needed if they have craniosynostosis.

Helmet therapy

Do not purchase any helmet devices on your own. Only a doctor can prescribe these helmets, and they are used in a small number of cases.

A lightweight helmet is made by an orthotist using 3D images and fitted for your baby. The helmet helps to reshape the skull by taking pressure off the flat area and allowing the skull to grow into the space provided.

Helmet therapy is most effective if treatment starts between six and eight months of age and is completed before 12 months, as this is the time of rapid growth of the skull.

Wearing the helmet doesn’t hurt and babies usually get used to it very quickly. Parents can sometimes feel quite emotional when their baby first wears the helmet. It can be helpful to know this is a common feeling and to remember treatment is temporary and outcomes are normally very good.

When your baby first gets their helmet, it will usually be worn for a two-hours-on/two-hours-off cycle for the first two days. This will allow you to monitor your baby’s skin and give your baby time to get used to the helmet. Following a review around two days after fitting, your baby will start wearing the helmet 23 hours a day. The orthotist will then review your baby about every three weeks.

Caring for your baby during helmet therapy:

- There should be some space in the helmet for your baby’s ears. Make sure their ears sit comfortably in these spaces and the helmet is not twisted.

- When you take the helmet off, check your baby’s skin to make sure there is no rubbing, blisters or broken skin. Mild redness over the high spots of the head is normal.

- You can put sorbolene cream on dry skin or mild rashes. You can buy sorbolene from a chemist or larger supermarkets. If the dry skin or rash does not get better, call your baby’s orthotist.

- Rather than taking the helmet off during hot weather, it is better to dress your baby in light clothing to keep them cool.

- Your baby’s head will become sweaty under the helmet. You should wash their hair daily and clean the inside of the helmet with a soft nailbrush or face washer and warm, soapy water. Rinse the helmet well and towel dry.

Figure 6. Plagiocephaly helmet therapy

Plagiocephaly long-term outcomes

To date, no studies have shown that the flattened area of the skull leads to any compromise in neurocognitive function. Once your baby can sit independently, the flattening will not worsen. As your child grows, you will notice that the flattening seems to improve. The head may never be symmetrical, but your child’s face will become more noticeable, his hair will grow and he will become more active. By school age, the flattening is usually no longer a cosmetic issue.

References- Ghizoni E, Denadai R, Raposo-Amaral CA, Joaquim AF, Tedeschi H, Raposo-Amaral CE. Diagnosis of infant synostotic and nonsynostotic cranial deformities: a review for pediatricians. Diagnóstico das deformidades cranianas sinostóticas e não sinostóticas em bebês: uma revisão para pediatras. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2016;34(4):495‐502. doi:10.1016/j.rpped.2016.01.004 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5176072

- Losee JE, Mason AC. Deformational plagiocephaly: diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 2005;32:53–64.

- Matushita H, Alonso N, Cardeal DD, Andrade FG. Major clinical features of synostotic occipital plagiocephaly: mechanisms of cranial deformations. Childs Nerv Syst. 2014;30:1217–1224.

- Wilbrand JF, Schmidtberg K, Bierther U, Streckbein P, Pons-Kuehnemann J, Christophis P, Hahn A, Schaaf H, Howaldt HP. Clinical classification of infant nonsynostotic cranial deformity. J Pediatr. 2012;161(6):1120–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.023

- Kim HY, Chung YK, Kim YO. Effectiveness of Helmet Cranial Remodeling in Older Infants with Positional Plagiocephaly. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2014;15(2):47‐52. doi:10.7181/acfs.2014.15.2.47 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5556813

- McKinney CM, Cunningham ML, Holt VL, Leroux B, Starr JR. Characteristics of 2733 cases diagnosed with deformational plagiocephaly and changes in risk factors over time. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2008;45:208–216.

- van Vlimmeren LA, van der Graaf Y, Boere-Boonekamp MM, L’Hoir MP, Helders PJ, Engelbert RH. Risk factors for deformational plagiocephaly at birth and at 7 weeks of age: a prospective cohort study. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e408–e418.

- Craniosynostosis Information Page. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Craniosynostosis-Information-Page

- Slater BJ, Lenton KA, Kwan MD, Gupta DM, Wan DC, Longaker MT. Cranial sutures: a brief review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:170e–178e.

- Starr JR, Collett BR, Gaither R, Kapp-Simon KA, Cradock MM, Cunningham ML, et al. Multicenter study of neurodevelopment in 3-year-old children with and without single-suture craniosynostosis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:536–542.

- Persing JA. MOC-PS(SM) CME article: management considerations in the treatment of craniosynostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(Suppl. 4):1–11.

- Warren SM, Proctor MR, Bartlett SP, Blount JP, Buchman SR, Burnett W, et al. Parameters of care for craniosynostosis: craniofacial and neurologic surgery perspectives. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:731–737.

- Bialocerkowski AE, Vladusic SL, Wei Ng C. Prevalence, risk factors, and natural history of positional plagiocephaly: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50(8):577–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03029.x

- De Bock F, Braun V, Renz-Polster H. Deformational plagiocephaly in normal infants: a systematic review of causes and hypotheses. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102(6):535–542. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-312018

- Argenta L, David L, Wilson J, Bell W. An increase in infant cranial deformity with supine sleeping position. J Craniofac Surg. 1996;7(1):5–11. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199601000-00005

- Mawji A, Vollman AR, Hatfield J, McNeil DA, Sauve R. The incidence of positional plagiocephaly: a cohort study. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):298–304. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3438

- Hutchison BL, Hutchison LA, Thompson JM, Mitchell EA. Plagiocephaly and brachycephaly in the first two years of life: a prospective cohort study. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):970–980. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0668-F

- Hutchison BL, Stewart AW, Mitchell EA. Deformational plagiocephaly: a follow-up of head shape, parental concern and neurodevelopment at ages 3 and 4 years. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(1):85–90. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.190934

- Bredero-Boelhouwer H, Treharne LJ, Mathijssen IM. A triage system for referrals of pediatric skull deformities. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:242–245.

- Pogliani L, Mameli C, Fabiano V, Zuccotti GV. Positional plagiocephaly: what the pediatrician needs to know. A review. Childs Nerv Syst. 2011;27:1867–1876.

- Medina LS, Richardson RR, Crone K. Children with suspected craniosynostosis: a cost-effectiveness analysis of diagnostic strategies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:215–221.

- Mathijssen IM. Guideline for care of patients with the diagnoses of craniosynostosis: working group on craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26:1735–1807.

- Tamburrini G, Caldarelli M, Massimi L, Santini P, Di Rocco C. Intracranial pressure monitoring in children with single suture and complex craniosynostosis: a review. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:913–921.