Post vasectomy pain syndrome

Post-vasectomy pain syndrome is widely known as either constant or intermittent testicular pain for greater than three months 1. Post-vasectomy pain syndrome pain interferes with quality of life and requires some degree of medical treatment in approximately 1–2% of men who undergo vasectomy 2. However, the incidence of post vasectomy pain syndrome is difficult to estimate due to the lack of prospective studies 3. One prospective study cites up to 15% of men suffering from post vasectomy pain syndrome after vasectomy, although the estimate appears much higher than any of the other series 4.

Post-vasectomy pain syndrome has been associated with histological findings such as thickened cellular basement membranes, testicular interstitial fibrosis, and degeneration of the spermatids 5. The actual mechanism of post vasectomy pain syndrome is thought to be multifactorial and includes direct spermatic cord damage, inflammation of spermatic cord nerves, epididymal congestion, perineural fibrosis, epididymal blowout, and the development of anti-sperm antibodies as well as possible psychological factors 6.

Post-vasectomy pain syndrome is diagnosis of exclusion, and may be caused by direct damage to spermatic cord structures, compression of nerves in the spermatic cord via inflammation, back pressure from epididymal congestion, and perineural fibrosis.

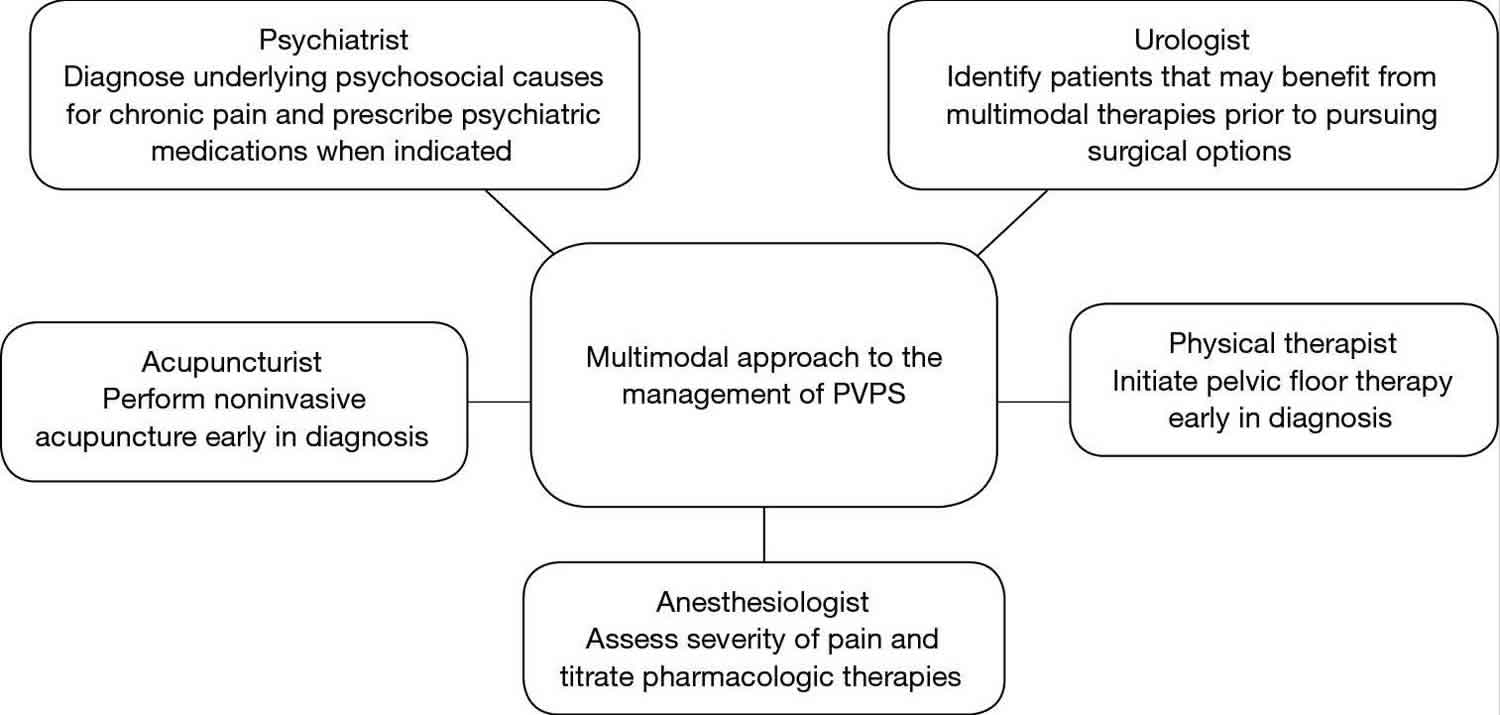

Post-vasectomy pain syndrome treatment should begin with the most noninvasive options and progress towards surgical management if symptoms persist (Figure 1). Noninvasive therapies include acupuncture, pelvic floor therapy and pharmacologic options.

Figure 1. Post vasectomy pain syndrome treatment options

Abbreviation: PVPS = post-vasectomy pain syndrome

[Source 3 ]Post vasectomy pain syndrome cause

The cause of post vasectomy pain syndrome is somewhat uncertain. The similar histologic findings in many post vasectomy pain syndrome patients, including thickened basement membranes, spermatid degeneration and testicular interstitial fibrosis, support a pathologic, not psychologic, etiology for this diagnosis 7.

Some of the proposed mechanisms thought to cause post vasectomy pain syndrome include direct damage to spermatic cord structures, compression of nerves in the spermatic cord via inflammation, back pressure from epididymal congestion, and perineural fibrosis 4. Unalleviated back pressure on the proximal stump of the vas deferens may cause sperm granulomas or epididymal blowout 8. There may also be an immunological component to the etiology of post vasectomy pain syndrome via the formation of antisperm antibodies. Following the disruption of the blood-testes barrier during vasectomy, 60–80% of men have detectable levels of serum antisperm antibodies. These antibodies have been shown to trigger organized immune responses in animal models 9. These potential mechanisms, either isolated or jointly, may ultimately lead to prolonged testicular or epididymal pain post-vasectomy.

Post vasectomy pain syndrome symptoms

Post vasectomy pain syndrome main symptoms are intermittent or constant testicular pain that is significantly bothersome to the patient for greater than three months. Signs and symptoms of post vasectomy pain syndrome include a tender vas deferens and/or epididymis, fullness of the vas deferens, orchialgia, dyspareunia, pain with ejaculation, premature ejaculation, and pain with straining. Scrotal ultrasound may show engorgement or thickening of the epididymis 10. Post-vasectomy pain syndrome pain interferes with quality of life and requires some degree of medical treatment in approximately 1–2% of men who undergo vasectomy 2.

Post vasectomy pain syndrome diagnosis

It is crucial to differentiate acute post-operative pain from post vasectomy pain syndrome. The most common symptom of post vasectomy pain syndrome is persistent orchalgia greater than three months after surgery, however, some patients present with pain with ejaculation, intercourse or erection. The differential diagnoses for these patients include neuropathic pain, infection, hydrocele, varicocele, inguinal hernia, intermittent testicular torsion, prostatitis, and psychogenic causes. Patients with post vasectomy pain syndrome often have a tender and/or full epididymis, tender proximal vas deferens, or palpable granuloma 11. With a detailed history and physical exam serially for several months following vasectomy, a diagnosis of post vasectomy pain syndrome can be safely made.

Ultimately, the diagnosis of post vasectomy pain syndrome is most safely made as a diagnosis of exclusion. A thorough history and physical is required at least three months after surgery. All patients with chronic testicular pain should undergo scrotal ultrasound with Doppler color-flow. Routine urinalysis, urine culture and semen culture should be obtained to rule out infection. In cases of concomitant neurological symptoms, MRI is recommended to rule out nerve impingement. To isolate the scrotum as the origin for pain, a spermatic cord block may be performed. This entails injecting 10 cc of 1% lidocaine without epinephrine into the cord at its location 1cm medial to the pubic tubercle and injecting 0.9% normal saline as a placebo injection. If pain subsides after injection of lidocaine up to 1–2 days, then cord block can serve as a diagnostic test in confirming that the pain is referred to the scrotum via nerves within the spermatic cord and predict response to spermatic cord denervation. Thus, a comprehensive evaluation is warranted to best establish a diagnosis in patients with chronic testicular pain.

Post vasectomy pain syndrome treatment

Management of post vasectomy pain syndrome can be frustrating for both the clinician and the patient. Treatment should begin with the most noninvasive options and progress towards surgical management if symptoms persist 3.

Nonsurgical treatments

Nonsurgical treatments include both pharmacotherapy and nonsurgical modalities to alleviate pain. Conservative therapy includes heat, ice, scrotal elevation, analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antidepressants (doxepin or amitriptyline), anticonvulsants (gabapentin and pregabalin), regional and local nerve blocks, pelvic floor physical therapy, biofeedback, acupuncture, and psychotherapy for at least 3 months. While conservative therapy has almost always been considered first-line treatment, success is relatively poor ranging from 4.2% to 15.2% in some studies. There are no good, published studies regarding reliable non-surgical interventions. Nevertheless, it is advisable to try conservative therapies first.

Treatment starts with dietary and lifestyle advice usually consisting of eliminating dietary caffeine, citrus, hot spices, and chocolate as well as avoidance of constipation and prolonged sitting.

Medical treatment usually begins with scheduled non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for 4–6 weeks 3. NSAIDs are typically prescribed for at least 30 days. Preferred agents include 600 mg ibuprofen 3 times daily, naproxen (Naprosyn), celecoxib 200 mg daily or piroxicam (Feldene) 20 mg daily. Recurrence rates after successful NSAID use are as high as 50%. Narcotic analgesics should be avoided except possibly for occasional breakthrough pain. There is some evidence than tamsulosin may be of some use in selected patients.

If NSAIDs do not improve testicular pain, the second line medication recommended is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) or gabapentin. Some small retrospective studies have shown some improvement in patients with post vasectomy pain syndrome. Tricyclic antidepressants have been proven to decrease neuropathic pain in other pathologies, including diabetic neuropathy and post herpetic neuralgia, by inhibiting the channels that link the neuronal synapses necessary in generating pain 12. Tricyclic antidepressants work by blocking the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin in the brain. Their analgesic effect is thought to be due to inhibition of sodium and L-type calcium channel blockers in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Tertiary amines in this class (amitriptyline and clomipramine) are more effective for neuropathic pain than secondary amines (desipramine and nortriptyline) but are also more sedating and more likely to be associated with postural hypotension. They are usually given as a single dose at bedtime and will typically require at least 2 to 4 weeks for their effectiveness to become apparent although this may take up to 8 weeks. Usual dosing is amitriptyline 25 mg at bedtime 13.

Anticonvulsants such as gabapentin have been recommended for relief from post vasectomy pain syndrome. If tricyclic therapy is not successful after 30 days, the next conservative therapy approach would be to add an anticonvulsant such as gabapentin (Neurontin) at 300 mg three times daily and pregabalin (Lyrica) at 75 to 150 mg daily. Usually, gabapentin is used first as insurance coverage often requires a gabapentin failure before pregabalin will be covered. These are recommended due to their proven efficacy in neuropathic pain and their relative lack of side effects. They work by modulating the N-type calcium channels which significantly affects pain fibers. Typical dosage of pregabalin for pain control would be 75 mg 3 times daily. If the pain persists beyond 30 days, the treatment would be judged ineffective. However, in one small study 14, over 60% of patients with idiopathic chronic testicular pain rather than pain from post vasectomy pain syndrome.

Long-term use of narcotic pain medication is not recommended as a sustainable treatment option for patients with chronic post vasectomy pain syndrome 3.

Either exclusively or in combination with pharmacotherapy, pelvic floor therapy and/or acupuncture may be offered to patients with post vasectomy pain syndrome 3. Pelvic floor physical therapy is useful for those with pelvic muscle dysfunction or identifiable myofascial trigger points. In properly selected patients, about 50% have noted improvement in their pain after 12 sessions. It also appears that physical therapy can improve pain and quality of life scores for chronic orchialgia patients even after other treatments. Therefore, a physical therapy evaluation and treatment should be considered an effective, low risk therapeutic option for patients with chronic orchialgia 15. Although there are no clinical trials proving the effectiveness of these modalities in post vasectomy pain syndrome, they are noninvasive and safe options to offer patients early in their diagnosis. Additionally, psychiatric evaluation may be warranted to rule out any mood disorder.

These nonsurgical treatment options are typically not long-lasting. Failed pharmacotherapy and noninvasive modalities should trigger surgical intervention.

The next step is the spermatic cord block which is recommended prior to performing any invasive or irreversible surgical procedures. This is usually done by injection 20 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine without epinephrine using a 27 gauge needle. Steroids may or may not be added. The injection is done directly into the spermatic cord at the level of the pubic tubercle. Ultrasound can be used to assist if the anatomy is challenging due to body habitus or prior surgery. If spermatic cord nerves are involved in the pain signals, the testicular discomfort should be rapidly relieved by the injection. While this often provides relief, it is rarely long term. Those patients who experience more than 90% pain relief can be offered repeated blocks up to every 2 weeks. If the injection provides no pain relief, it is not repeated. If the spermatic cord block is not at least 50% successful in reducing the orchialgia, consider a possible missed diagnosis. A re-examination of the patient along with a careful review of his laboratory studies and imaging is suggested. In general, the better the response to the spermatic cord block, the better the outcome with microdenervation of the spermatic cord. The use of “sham blocks,” with normal saline instead of local anesthetic, is discouraged due to ethical considerations 16.

Surgical intervention is indicated if the spermatic cord block is at least 50% successful in reducing the orchialgia.

Surgical treatments

Surgical options include excision of sperm granuloma, microdenervation of spermatic cord, epididymectomy, vasovasostomy and in severe cases, orchiectomy. Of note, it is crucial to counsel patients that surgical interventions are not guaranteed to completely relieve pain and symptoms of the post vasectomy pain syndrome may continue or even worsen after surgery. This risk is particularly essential to document in all surgical informed consents (Table 1).

Table 1. Ideal patient selection for each surgical treatment option for post vasectomy pain syndrome

| Surgical treatment option | Patient selection |

|---|---|

| Excision of sperm granuloma | Palpable sperm granuloma on physical exam |

| Microdenervation of the spermatic cord | Successful temporary relief with spermatic cord block |

| Epididymectomy | Pain localized to epididymis and not cord and/or testicle |

| Vasovasostomy | No concern for possibility for future fertility |

| Orchiectomy | Failed all other medical and surgical treatment options |

Microdenervation of the spermatic cord

Microdenervation of the spermatic cord is the precise transection of all nerves within the spermatic cord. Care is taken to avoid all vasculature and lymphatic drainage. Microdenervation of the spermatic cord is useful in identifying intra-scrotal pathology as the etiology for scrotal pain. Patients who had effective temporary relief with spermatic cord block predicted a successful microdenervation of the spermatic cord. One study specifically evaluated the use of microdenervation of the spermatic cord in patients with post vasectomy pain syndrome. This study by Ahmed et al. performed microdenervation of the spermatic cord on 17 patients with post vasectomy pain syndrome, and 76.5% of patients had complete resolution of pain at first follow-up visit 17. Several other studies have proven the effectiveness of microdenervation of the spermatic cord in patients with various causes for chronic testicular pain (orchialgia) 18.

Epididymectomy

Epididymectomy is most effective when pain is localized to the epididymis and not diffused around the entire cord or testicle. Several studies have been conducted to demonstrate the role of epididymectomy in treating post vasectomy pain syndrome. One study by Chung et al performed epididymectomy with simultaneous injection of hyaluronic acid and carboxymethyl cellulose to prevent fibrosis in post vasectomy pain syndrome patients, and this resulted in even better pain relief results 19.

Vasectomy reversal

Vasectomy reversal or vasovasostomy, has been shown to significantly improve pain in patients with post vasectomy pain syndrome. This method directly alleviates the back pressure caused by obstruction at the proximal stump of the vas deferens. Many single-center studies demonstrate the high effectiveness of vasovasostomy, with up to 93% of patients reporting improvement of pain 20. The obvious downside of this treatment option is the return of initially unwanted fertility. Additionally, this option may not be covered by health insurance, thus making it cost prohibitive for patients with post vasectomy pain syndrome.

Orchiectomy

Orchiectomy serves as a last resort for relief of post vasectomy pain syndrome if all other surgical options have failed in resolving symptoms. Inguinal orchiectomy is preferred over scrotal orchiectomy due to higher likelihood of complete resolution of pain post-operatively 21. Although effective, the hormonal effects of this radical therapy make this an option only after exhausting all other medical and surgical options.

References- Tan WP, Levine LA. An overview of the management of post-vasectomy pain syndrome. Asian J Androl 2016;18:332-7. 10.4103/1008-682X.175090

- Sharlip ID, Belker AM, Honig S, et al. American urological association. Vasectomy: AUA guideline. J Urol 2012;188:2482-91. 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.080

- Sinha V, Ramasamy R. Post-vasectomy pain syndrome: diagnosis, management and treatment options. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6(Suppl 1):S44–S47. doi:10.21037/tau.2017.05.33 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5503923

- Leslie TA, Illing RO, Cranston DW, et al. The incidence of chronic scrotal pain after vasectomy: a prospective audit. BJU Int 2007;100:1330-3. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07128.x

- Leslie SW, Sajjad H, Siref LE. Chronic Testicular Pain (Orchialgia) [Updated 2019 Oct 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482481

- Tan WP, Levine LA. Micro-Denervation of the Spermatic Cord for Post-Vasectomy Pain Management. Sex Med Rev. 2018 Apr;6(2):328-334.

- Whyte J, Sarrat R, Cisneros AI, et al. The vasectomized testis. Int Surg 2000;85:167-74.

- Kathrins M. Techniques and complications of elective vasectomy: the role of spermatic granuloma in spontaneous recanalization. Fertil Steril 2016;106:68-9. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.04.030

- Linnet L, Hjort T. Sperm agglutinins in seminal plasma and serum after vasectomy: correlation between immunological and clinical findings. Clin Exp Immunol 1977;30:413-20.

- Tan WP, Levine LA. An overview of the management of post-vasectomy pain syndrome. Asian J Androl. 2016;18(3):332–337. doi:10.4103/1008-682X.175090 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4854072

- Nangia AK, Myles JL, Thomas AJ. Vasectomy reversal for the post-vasectomy pain syndrome: a clinical and histological evaluation. J Urol 2000;164:1939-42. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66923-6

- Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Audette J, et al. Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:S3-14. 10.4065/mcp.2009.0649

- Sinclair AM, Miller B, Lee LK. Chronic orchialgia: consider gabapentin or nortriptyline before considering surgery. Int. J. Urol. 2007 Jul;14(7):622-5.

- Sinclair AM, Miller B, Lee LK. Chronic orchialgia: consider gabapentin or nortriptyline before considering surgery. Int J Urol 2007;14:622-5. 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01745.x

- Basal S, Ergin A, Yildirim I, Goktas S, Atim A, Sizlan A, Irkilata HC, Kurt E, Dayanc M. A novel treatment of chronic orchialgia. J. Androl. 2012 Jan-Feb;33(1):22-6.

- Benson JS, Abern MR, Larsen S, Levine LA. Does a positive response to spermatic cord block predict response to microdenervation of the spermatic cord for chronic scrotal content pain? J Sex Med. 2013 Mar;10(3):876-82.

- Ahmed I, Rasheed S, White C, Shaikh NA. The incidence of post-vasectomy testicular pain and the role of nerve stripping (denervation) of the spermatic cord in its management. Br J Urol 1997;79:269-70. 10.1046/j.1464-410X.1997.32221.x

- Strom KH, Levine LA. Microsurgical denervation of the spermatic cord for chronic orchialgia: long-term results from a single center. J Urol 2008;180:949-53. 10.1016/j.juro.2008.05.018

- Chung JH, Moon HS, Choi HY, et al. Inhibition of adhesion and fibrosis improves the outcome of epididymectomy as a treatment for chronic epididymitis: a multicenter, randomized controlled, single-blind study. J Urol 2013;189:1730-4. 10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.168

- Horovitz D, Tjong V, Domes T, et al. Vasectomy reversal provides long-term pain relief for men with the post-vasectomy pain syndrome. J Urol 2012;187:613-7. 10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.023

- Davis BE, Noble MJ, Weigel JW, et al. Analysis and management of chronic testicular pain. J Urol 1990;143:936-9.