Postcholecystectomy syndrome

Postcholecystectomy syndrome is defined a heterogeneous group of symptoms and findings such the recurrence of symptoms of upper abdominal pain (mainly right upper quadrant) and dyspepsia, with or without jaundice, in patients who have previously undergone cholecystectomy 1. Although rare, many of these complaints can be attributed to complications including bile duct injury, biliary leak, biliary fistula and retained bile duct stones 1. Late complications include recurrent bile duct stones and bile duct strictures. With the number of cholecystectomies being performed increasing in the laparoscopic era the number of patients presenting with postcholecystectomy syndrome is also likely to increase.

In general, postcholecystectomy syndrome is a preliminary diagnosis and should be renamed with respect to the disease identified by an adequate workup 2. Postcholecystectomy syndrome arises from alterations in bile flow due to loss of the reservoir function of the gallbladder. Two types of problems may arise. The first is continuously increased bile flow into the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which may contribute to esophagitis and gastritis. The second is related to the lower gastrointestinal tract, where diarrhea and colicky lower abdominal pain may result 3.

Postcholecystectomy syndrome reportedly affects about 10-15% of patients 2. However, the incidence of postcholecystectomy syndrome has been reported to be as high as 40% in one study, and the onset of symptoms may range from 2 days to 25 years 4. Effective communication between patients and their physicians, with specific inquiry directed at eliciting frequently anticipated postoperative problems, may be necessary to reveal the somewhat subtle symptoms of postcholecystectomy syndrome.

Treatment should be governed by the specific diagnosis made and may include pharmacologic or surgical approaches.

Postcholecystectomy syndrome causes

The most common cause of postcholecystectomy syndrome is an overlooked extrabiliary disorder such as reflux oesophagitis, peptic ulceration, irritable bowel syndrome or chronic pancreatitis 5. The biliary causes include:

- Biliary strictures

- Bile leakage

- Retained calculi

- Dropped calculi

- Chronic biloma or abscess

- Long cystic duct remnant

- Stenosis or dyskinesia of the sphincter of Oddi

- Bile salt-induced diarrhoea or gastritis

Bile duct injuries are the most serious complications associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with a rate of occurrence as low as 0.2% but usually ranging from 0.4% to 4% for most surgeons 6. Many injuries may go unrecognized until the patient gets referred with symptoms of abdominal pain, sepsis or jaundice soon after cholecystectomy. Bile duct injuries may manifest in one of two ways: biliary duct obstruction or bile leakage.

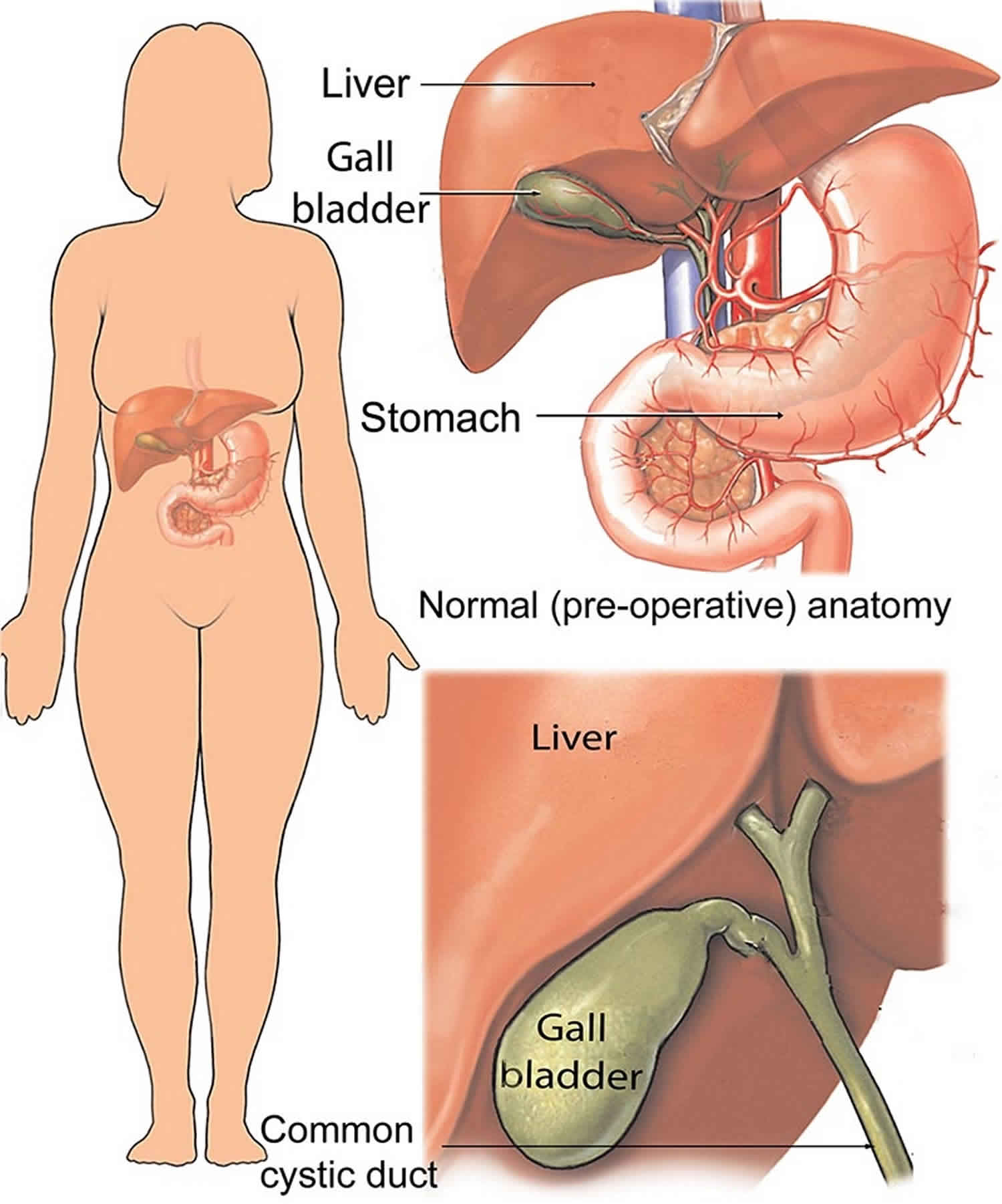

Acute biliary obstruction and bile duct injury is twice as common with laparoscopic cholecystectomy as with open cholecystectomy 7. The classic injury occurs when the surgeon mistakes the common hepatic duct for the cystic duct. In these patients, radiological studies usually show diffuse or segmental intrahepatic duct dilatation and surgical clips at the point of obstruction.

The incidence of late strictures of extrahepatic ducts has substantially increased, perhaps as a result of the widespread use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.9 Thermal injury may result in acute bile duct necrosis and bile leakage, but mild injury may result in fibrosis. Furthermore, the clips themselves may rarely induce fibrosis or inflammatory changes around the extrahepatic ducts that might cause a stricture.

There is little information on the natural history of common bile duct stones , however, the incidence of retained/recurrent calculi ranges from 1.2% to 14% with only approximately 0.3% ever causing symptoms 8. Although magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is valuable in the preoperative evaluation of common bile duct stones, it is not routinely carried out because of cost-benefit concerns. Common bile duct exploration and/or on-table cholangiography can be performed during laparoscopic cholecystectomy but are not done so routinely unless there is a clear indication. If an on-table cholangiography demonstrates stones in the common bile duct then either the surgeon can proceed to common bile duct exploration or post-operative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Rarely, small calculi may migrate into the common bile duct in patients with a patulous cystic duct when the gallbladder is pulled cephalad during dissection. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is effective in diagnosing such cases and can offer therapeutic options as well.

Spillage of gallstones may occur during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with a reported incidence of 0.1–20% 9. Fortunately, most of these stones are asymptomatic, although if spillage does occur every effort should be made to retrieve the stones in view of the small risk of developing significant complications. The most common of which is abscess formation either in the abdominal wall or in the peritoneum. Spilled gallstones have also presented after erosion through the skin 10. as a colovesical fistula 11 and as the cause of an incarcerated hernia 12.

Dropped gallstones leading to abscess formation can occur after a period of months to years after surgery which can make the diagnosis difficult. Spilled gallstones appear as small hyperechoic lesions on ultrasound scanning that may be related to fluid collections and are found most often in the subdiaphragmatic or subhepatic spaces. If they are calcified, they may also be seen on CT as hyperdense areas or on T1-weighted MRI as a signal void.

Several reports have proposed that a cystic duct remnant >1 cm in length after cholecystectomy may be responsible, as least in part, for postcholecystectomy syndrome – “cystic duct stump syndrome”. There have been reports of a cystic duct remnant causing symptoms even after the duct calculi had been removed 13. These authors also reported examples of the presence of stones within both the cystic duct remnant and the common bile duct and suggested that stones could be formed within the cystic duct remnant. Pain in the right upper quadrant was found to be the outstanding symptom and jaundice the commonest sign. The estimated incidence of a retained stone within the cystic duct remnant is <2.5% 14. To date there does not appear to be an increased risk of cystic duct remnant calculi in patients who have undergone laparoscopic cholecystectomy compared to patients who have undergone open cholecystectomy.

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction has been implicated in the aetiology of postcholecystectomy syndrome. Such dysfunction can result from a true stenosis or secondary to spasm of the sphincter. In the majority of cases, the dysfunction continues to present problems both in terms of diagnosis as well as treatment. Although muscle spasm is thought to play a significant role in these cases, the response to smooth muscle relaxants such as nitrates and calcium channel antagonists has been disappointing 15. Sphincterotomy is considered to be the most effective treatment. However, there are significant risks associated with this such as bleeding and pancreatitis. This makes it necessary for the endoscopist to conclusively establish the diagnosis prior to sphincterotomy. Currently, the only reliable method is by biliary manometry which unfortunately is both difficult to perform and associated with considerable discomfort to the patient. Furthermore, it carries its own risk of pancreatitis. In addition to this, even if manometric evidence of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction is obtained, it does not always prove that it is the cause of the patient’s symptoms 16. This is somewhat unsurprising given that sphincter of Oddi dysfunction may be associated with bowel dysmotility such as gastroparesis and oesophageal motility disorders.

Postcholecystectomy syndrome prevention

Many articles have stated that a complete preoperative evaluation is essential to minimizing the incidence of postcholecystectomy syndrome and that patients should be warned of the possibility of symptoms after cholecystectomy, which may start at any time from the immediate postoperative period to decades later.

Many studies have also been performed in an attempt to identify those at increased risk for postcholecystectomy syndrome and to develop a method of risk stratification. To a large extent, the data are inconsistent from study to study; however, it is generally considered that the more secure the preoperative diagnosis, the lower the risk of postcholecystectomy syndrome. Other reports find a cause for postcholecystectomy syndrome in as many as 95% of patients.

Since the development of oral cholecystography in the 1920s as a preoperative aid in the detection of stones or nonfunctioning gallbladders, a wide variety of noninvasive imaging techniques have proven useful in preoperative gallbladder assessment. Ultrasonography is the most accessible and cost-effective approach in most institutions. Other noninvasive techniques include the following:

- Hepatobiliary scintigraphy with technetium-99m ( 99mTc)-labeled iminodiacetic acid (ie, hepatoiminodiacetic acid [HIDA] scanning) 17, with and without calculation of cholecystokinin (CCK)-stimulated ejection fraction (EF)

- Computed tomography (CT), including helical or spiral CT

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

More invasive procedures that may prove valuable in defining the biliary anatomy include the following:

- Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and ERCP, with and without biliary and ampullary manometry and sphincterotomy

- Intraoperative cholangiogram

These procedures have helped reduce the incidence of postcholecystectomy syndrome by facilitating better preoperative evaluation and diagnosis, especially in patients without stones.

As technology and understanding of the functional disorders of the gastrointestinal and biliary tracts improve, the ability to make a diagnosis and to treat discovered illnesses will improve as well. postcholecystectomy syndrome will be a less frequent diagnosis as patients are more efficiently screened and evaluated and as specific diagnoses are confirmed.

Postcholecystectomy syndrome symptoms

A wide range of symptoms may be noted in patients with postcholecystectomy syndrome. Symptoms are sometimes considered to be associated with the gallbladder. Freud found colic in 93% of patients, pain in 76%, jaundice in 24%, and fever in 38% 18. In the author’s patient population, the incidence of postcholecystectomy syndrome is 14%. Pain is found in 71% of patients, diarrhea or nausea in 36%, and bloating or gas in 14%. The cause of postcholecystectomy syndrome is identifiable in 95% of patients.

Postcholecystectomy syndrome diagnosis

The workup for postcholecystectomy syndrome varies. An extensive study of the patient should be performed in an attempt to identify a specific cause for the symptoms and to exclude serious postcholecystectomy complications. Surgical reexploration should be considered a last resort.

Patient examination starts with a thorough history and a careful physical examination, with close scrutiny of the old record. Particular attention should be paid to the preoperative workup and diagnosis, the surgical findings and pathologic examination, and any postoperative problems. Discrepancies may lead to the diagnosis. Additional workup is directed at the most likely diagnosis while excluding other possible causes.

Laboratory studies

Initial laboratory studies in the workup for postcholecystectomy syndrome usually include the following:

- Complete blood count (CBC) to screen for infectious etiologies

- Basic metabolic panel and amylase level to screen for pancreatic disease

- Hepatic function panel (liver function test) and prothrombin time (PT) to screen for possible liver or biliary tract diseases

- If the patient is acutely ill, blood gas analysis

If laboratory findings are within reference ranges, consideration should be given to repeating these studies when symptoms are present.

Other laboratory studies that may be indicated are as follows:

- Lipase

- Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT)

- Hepatitis panel

- Thyroid function

- Cardiac enzymes

Ultrasonography

An ultrasonographic study is almost always performed; it is a quick, noninvasive, and relatively inexpensive way to evaluate the liver, biliary tract, pancreas, and surrounding areas. A 10- to 12-mm dilation of the common bile duct is commonly observed. Dilation exceeding 12 mm is often diagnostic of distal obstruction, such as a retained stone, common bile duct stricture, or ampullary stenosis.

In a study of 80 patients with postcholecystectomy syndrome, Filip et al 19 concluded that endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) was a valuable tool for determining which patients require endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The sensitivity and specificity of EUS (endoscopic ultrasonography) were found to be 96.2% and 88.9%, respectively, in a subset of 53 patients who were ultimately diagnosed with biliary or pancreatic disease. The investigators found that the use of endoscopic ultrasonography helped to reduce the number of patients receiving ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) by 51%.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the most useful test in the diagnosis of postcholecystectomy syndrome 20. It is unsurpassed in visualization of the ampulla, biliary, and pancreatic ducts. At least 50% of patients with postcholecystectomy syndrome have biliary disease, and most of these patients’ conditions are functional in nature. An experienced endoscopist can confirm this diagnosis in most of these patients and can also provide additional diagnostic studies, such as biliary and ampullary manometry.

Delayed emptying can be observed during ERCP, as well as with hepatoiminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scanning. The common bile duct should clear of contrast within 45 minutes. Biliary manometry is performed in patients sedated without narcotics with a perfusion catheter; a pull-through technique is used for sphincter manometry. The sphincter is 5-10 mm long, and normal pressures are less than 30 mm Hg.

As technology improves, it will be easier to detect retrograde contractions or increased frequency of contractions (also called tachyoddia).

At the time of ERCP, therapeutic maneuvers, such as stone extraction, stricture dilatation, or sphincterotomy for dyskinesia or sphincter of Oddi stenosis, can be performed. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) may be of use in patients who are not candidates for ERCP or in whom ERCP has been unsuccessfully attempted.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy can be very helpful in the workup of postcholecystectomy syndrome. It is a good procedure for evaluating the mucosa for signs of disease from the esophagus through the duodenum. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy also allows direct visualization of the ampulla of Vater.

A total colonoscopy may reveal colitis, and biopsy of the terminal ileum may confirm Crohn disease.

Radiography

Chest radiography should be performed to screen for lower-lung, diaphragmatic, and mediastinal diseases; in most cases, abdominal films should be obtained as well. In patients with a history of back problems or arthritis, a lower dorsal spine series should also be obtained.

For patients with right-upper-quadrant pain, barium swallow, upper gastrointestinal (GI), and small-bowel follow-through studies will evaluate the intestinal tract for evidence of esophagitis, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and peptic ulcer disease. These studies are not always performed, because esophagogastroduodenoscopy is more reliable at identifying these diseases and also permits direct visualization of the ampulla of Vater. When the pain is lower in the abdomen, a barium enema should be performed.

Angiography of suspected diseased vessels may lead to intervention for vascular disorders, such as coronary or intestinal angina.

CT and MRI scans

Computed tomography (CT) can be helpful in identifying chronic pancreatitis or pseudocysts in patients with alcoholism or those with a history of pancreatitis. In patients who are not candidates for esophagogastroduodenoscopy and ERCP, a helical CT scan or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) may reveal the cause of postcholecystectomy syndrome.

Nuclear imaging

Nuclear imaging may demonstrate a postoperative bile leak. Occasionally, a HIDA (hepatoiminodiacetic acid) scan or similar scintigraphic study may show delayed emptying or a prolonged half-time, but these studies lack the resolution necessary to identify dilation, stricture, and so on. Emptying delayed by more than 2 hours or a prolonged half-time can help identify the sphincter of Oddi as a potential cause but cannot differentiate between stenosis and dyskinesia.

Postcholecystectomy syndrome treatment

Postcholecystectomy syndrome is usually a temporary diagnosis. An organic or functional diagnosis is established in most patients after a complete workup. It should be remembered that cholecystectomy is associated with several physiological changes in the upper gastrointestinal tract which may account for the persistence of symptoms or the development of new symptoms after gallbladder removal. The cholecystosphincter of Oddi reflex 21, cholecysto-antral reflex 22 and cholecysto-oesophageal reflexes 23 are all disrupted and a number of local upper gastrointestinal hormonal changes also occur after cholecystectomy 24. Thus, there is an increased incidence of gastritis, alkaline duodenogastric reflux and gastro-oesophageal reflux after cholecystectomy, all of which may be the basis for postcholecystectomy symptoms. Once a diagnosis has been established, treatment should proceed as indicated for that diagnosis. Treatment may be either medical or surgical.

Patients with irritable bowel syndrome may benefit from the administration of bulking agents, antispasmodics, or sedatives. The irritable sphincter may respond to high-dose calcium channel blockers or nitrates, but the available evidence is not yet convincing. Cholestyramine has been helpful for patients with diarrhea alone.

Antacids, histamine 2 (H2) blockers, or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) can occasionally provide relief for patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or gastritis symptoms. One study showed that lovastatin might provide at least some relief in as many as 67% of patients.

For patients with dyspeptic symptoms, Abu Farsakh et al showed that symptoms correlated with gastric bile salt concentration 25.

Surgical intervention

Like medical therapy, surgical therapy should be directed at the specific diagnosis 26. Surgery is indicated when an identifiable cause of postcholecystectomy syndrome that is known to respond well to operative intervention has been established. The most commonly performed procedure is endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. Exploratory surgery is a last resort in the patient who lacks a diagnosis and whose condition proves refractory to medical therapy.

In 1947, Womack suggested resection of scar and nerve tissue around the cystic duct stump, though this method is somewhat controversial 27. Others suggested resection of neuroma, cystic duct remnant, sphincter dilation, sphincterotomy, sphincteroplasty, biliary bypass, common bile duct (CBD) exploration, and stone removal. With ERCP, most of these diagnoses would have been ruled out or treated, and the idea of amputation of neuroma was controversial.

Patients abusing alcohol or narcotics are especially difficult to manage, and exploratory surgery should be postponed until they have stopped abusing these drugs.

In a few patients, no causes are identifiable and exploration is unrevealing, but the condition may respond to sphincteroplasty, including the bile and pancreatic ducts. This group of patients is not yet identifiable preoperatively.

If, after a complete evaluation (including ERCP with sphincterotomy), a patient continues to experience debilitating, intermittent right-upper-quadrant pain, and no diagnosis is found, the procedure of choice after a normal exploratory laparotomy is transduodenal sphincteroplasty.

When postcholecystectomy syndrome (postcholecystectomy syndrome) results from remnant cystic duct lithiasis (ie, gallstones within the cystic duct after cholecystectomy), endoscopic therapy may suffice, but surgical excision of the remnant cystic duct lithiasis may be necessary in some cases 28.

Postcholecystectomy syndrome prognosis

Postcholecystectomy syndrome outcome and prognosis vary in accordance with the variety of patients and conditions encountered and the operations that may be performed.

Moody 29 showed that 75% of his patients had good-to-fair relief of pain on long-term follow-up. Short-term complications are common (5-40%). Hyperamylasemia is the most common complication but usually resolves by postoperative day 10. Pancreatitis is expected in 5% of cases and death in 1%.

References- Postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCS). International Journal of Surgery Volume 8, Issue 1, 2010, Pages 15-17 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.10.008

- Postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCS). International Journal of Surgery Volume 8, Issue 1, 2010, Pages 15-17 https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/192761-overview

- Walters JR, Tasleem AM, Omer OS, Brydon WG, Dew T, le Roux CW. A new mechanism for bile acid diarrhea: defective feedback inhibition of bile acid biosynthesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Nov. 7 (11):1189-94.

- P.H. Zhou, F.L. Liu, L.Q. Yao, X.Y. Qin. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of postcholecystectomy syndrome Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int, 2 (2003), pp. 117-120

- M.A. Rogy, R. Fugger, F. Herbst, F. Schulz. Reoperation after cholecystectomy. The role of the cystic duct stump HPB Surg, 4 (1991), pp. 129-135

- P.D. Thurley, D. Rajpal. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: postoperative imaging AJR, 191 (2008), pp. 794-801

- O. Fathy, M.A. Zeid, T. Abdallah. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a report on 2000 cases Hepatogastroenterology, 50 (2003), pp. 967-971

- A. Gerber, M.K. Apt. The case against routine operative cholangiography Am J Surg, 143 (1982), pp. 734-736

- J.G. Brockmann, T. Kocher, N.J. Senninger, G.M. Schurmann. Complications due to gallstones lost during laparoscopic cholecystectomy Surg Endosc, 16 (2002), pp. 1226-1232

- M. Yamamuro, B. Okamoto, B. Owens. Unusual presentations of spilled gallstones Surg Endosc, 17 (2003), p. 1498

- F. Daoud, Z.M. Awwad, J. Masad. Colovesical fistula due to a lost gallstone following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a report of a case Surg Today, 31 (2001), pp. 255-257

- M. Bebawi, S. Wassef, A. Ramcharan, K. Bapat. Incarcerated indirect inguinal hernia: a complication of spilled gallstones JSLS, 4 (2000), pp. 267-269

- R. Tritapepe, C. Pozzi, M. Montorsi, S.B. Doldi. The cystic dump stump syndrome reality or fantasy Ann Ital Chir, 60 (3) (1989), pp. 133-136

- Y.W. Lum, M.G. House, A.J. Hayanga, M. Schweitzer. Postcholecystectomy syndrome in the laparoscopic era J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech, 16 (5) (2006), pp. 482-485

- P.J. Pasricha, E.P. Miskovsky, A.N. Kalloo. Intrasphincteric injection of botulinum toxin for suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction Gut, 35 (1994), pp. 1319-1321

- W.A. Steinberg. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: a clinical controversy Gastroenterology, 95 (1988), pp. 1409-1415

- Mahid SS, Jafri NS, Brangers BC, Minor KS, Hornung CA, Galandiuk S. Meta-analysis of cholecystectomy in symptomatic patients with positive hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan results without gallstones. Arch Surg. 2009 Feb. 144 (2):180-7.

- Freud M, Djaldetti M, deVries A, Leffkowitz M. Postcholecystectomy syndrome: a survey of 114 patients after biliary tract surgery. Gastroenterologia. 1960. 93:288-93.

- Filip M, Saftoiu A, Popescu C, Gheonea DI, Iordache S, Sandulescu L, et al. Postcholecystectomy syndrome – an algorithmic approach. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009 Mar. 18 (1):67-71.

- Coelho-Prabhu N, Baron TH. Assessment of need for repeat ERCP during biliary stent removal after clinical resolution of postcholecystectomy bile leak. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Jan. 105(1):100-5.

- E.C. Muller, M.A. Lewinski, H.A. Pitt. The cholecystosphincter of Oddi reflex J Surg Res, 36 (1984), pp. 377-383

- T.H. Webb, K.D. Lillemoe, H.A. Pitt. Gastrosphincter of Oddi reflex Am J Surg, 155 (1988), pp. 193-198

- R. Stuart, P.J. Byrne, P. Marks, P. Lawlor, T.F. Gorey, T.P.J. Hennessey. Extrinsic pathology alters oesophageal motility in the dog Br J Surg, 77 (1990), p. A709

- T.E. Adrian, A.P. Savage, A.J. Bacarase-Hamilton, K. Wolfe, H.S. Besterman, S.R. Bloom. Peptide YY abnormalities in gastrointestinal disease Gastroenterology, 90 (1986), pp. 379-384

- Abu Farsakh NA, Stietieh M, Abu Farsakh FA. The postcholecystectomy syndrome. A role for duodenogastric reflux. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996 Apr. 22(3):197-201.

- Redwan AA. Multidisciplinary approaches for management of postcholecystectomy problems (surgery, endoscopy, and percutaneous approaches). Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009 Dec. 19(6):459-69.

- Womack NA, Crider RL. The persistence of symptoms following cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1947 Jul. 126(1):31-55.

- Phillips MR, Joseph M, Dellon ES, Grimm I, Farrell TM, Rupp CC. Surgical and endoscopic management of remnant cystic duct lithiasis after cholecystectomy–a case series. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014 Jul. 18(7):1278-83.

- Moody FG, Vecchio R, Calabuig R, Runkel N. Transduodenal sphincteroplasty with transampullary septectomy for stenosing papillitis. Am J Surg. 1991 Feb. 161(2):213-8.