What is referred pain

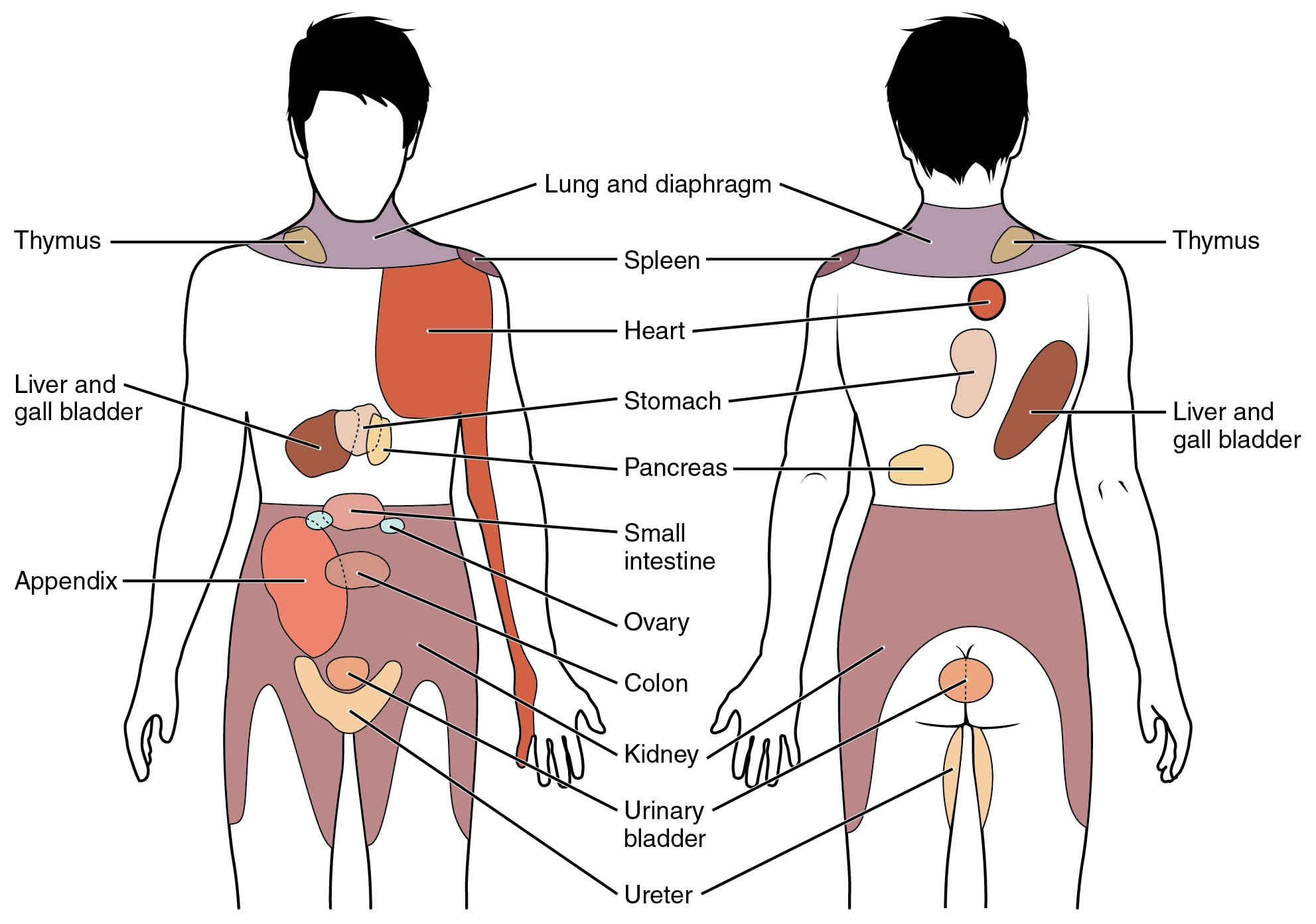

Referred pain is pain felt in one area of the body other than the site of the painful stimulus where the problem is because the pain may be referred there from another area. Referred pain is a segmental component of nociceptive pain perceived at a location remote from the original injury site 1. For example, a cervicogenic headache is a referred pain to the head or face from soft or bony cervical tissue 2. A pain produced by a heart attack may feel as if it is coming from the left arm and sometimes in the upper abdomen because sensory information from the heart and the left arm travel on the same nerve pathways in the spinal cord. Referred pain can also occur under less dramatic circumstances unrelated to any heart pathology. Ppain referral is frequently found in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain (for example, temporomandibular disorder, fibromyalgia, and chronic low back pain). In patients with temporomandibular disorder, for example, muscle and/or jaw joint pain could refer to the teeth and other parts of the orofacial area.

The phenomenon of referred pain can present a serious problem to both patients and physicians when it goes unrecognized. Because the source of the pain lies overlooked at a distant location, the lack of any demonstrable lesion at the site of pain and tenderness often leads to the suspicion that the pain has a strong psychological component. When health professionals insist that there is no reason for the pain, patients sometimes begin to wonder whether the pain is “all in their head.” This can exacerbate anxiety and other psychological reactions to the pain, is likely to frustrate both the doctor and the patient, and may lead to “doctor shopping” and inappropriate treatment.

- The size of referred pain is related to the intensity and duration of ongoing/evoked pain 3

- Temporal summation is a potent mechanism for generation of referred muscle pain 3

- Central hyperexcitability is important for the extent of referred pain 3

- Patients with chronic musculoskeletal pains have enlarged referred pain areas to experimental stimuli.[vague] The proximal spread of referred muscle pain is seen in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and very seldom is it seen in healthy individuals 3

- Modality-specific somatosensory changes occur in referred areas, which emphasize the importance of using a multimodal sensory test regime for assessment 3

- Referred pain is often experienced on the same side of the body as the source, but not always 4

Referred pain mechanism

At least four physiological mechanisms have been proposed to explain referred pain 5: (1) activity in sympathetic nerves, (2) peripheral branching of primary afferent nociceptors, (3) convergence projection, and (4) convergence facilitation. The latter two involve primarily central nervous system mechanisms.

- Sympathetic nerves may cause referred pain by releasing substances that sensitize primary afferent nerve endings in the region of referred pain 6, or possibly by restricting the flow of blood in the vessels that nourish the sensory nerve fiber itself.

- Peripheral branching of a nerve to separate parts of the body causes the brain to misinterpret messages originating from nerve endings in one part of the body as coming from the nerve branch supplying the other part of the body.

- According to the convergence-projection hypothesis, a single nerve cell in the spinal cord receives nociceptive input both from the internal organs and from nociceptors coming from the skin and muscles. The brain has no way of distinguishing whether the excitation arose from the somatic structures or from the visceral organs. It is proposed that the brain interprets any such messages as coming from skin and muscle nerves rather than from an internal organ. The convergence of visceral and somatic sensory inputs onto pain projection neurons in the spinal cord has been demonstrated 7.

- According to the convergence-facilitation hypothesis, the background (resting) activity of pain projection neurons in the spinal cord that receive input from one somatic region is amplified (facilitated) in the spinal cord by activity arising in nociceptors originating in another region of the body. In this model, nociceptors producing the background activity originate in the region of perceived pain and tenderness; the nerve activity producing the facilitation originates elsewhere, for example, at a myofascial trigger point. This convergence-facilitation mechanism is of clinical interest because one would expect that blocking sensory input in the reference zone with cold or a local anesthetic should provide temporary pain relief. One would not expect such relief according to the convergence-projection theory. Clinical experiments have demonstrated both kinds of responses.

Specific pathways and neural connections in the brain are thought to lead to the possibility of referred pain 8. Convergence is one of the important neural phenomena that plays a critical role in pain referral. To understand convergence it is necessary to understand how sensory information enters into and is processed in the brain. Information about touch and tissue damage is conveyed as action potentials along specific sensory nerve fibers that have their sensory receptors in the periphery (e.g. muscle, skin, joint, tooth pulp). One group of nerve fibers conveys information about touch and another group conveys information about tissue damage or noxious stimulation. The sensory nerve fibers conveying information about noxious stimuli are called nociceptive nerve fibers. Both the nociceptive and the touch nerve fibers convey action potentials into the brainstem to terminate on second order neurons in the trigeminal brainstem sensory nuclear complex. Once in the brainstem, 2 important things can happen. First, many nociceptive sensory fibers from different parts of the orofacial area can terminate on the same set of second order neurons, for example, nociceptive nerve fibers from jaw muscles, tooth pulps, and skin can all converge onto the same second order neuron. Second, both nociceptive and non-nociceptive (e.g. touch, pressure) sensory nerves can converge onto the same second order neuron.

The biological reason for this convergence is not totally clear but it appears to be at least part of the reason for referred pain. The second order neurons are part of the pathway that sends sensory information to higher centers for perception. However, since there is so much convergence of sensory information from different body parts onto the same second order neurons, these second order neurons may provide ambiguous information as to the exact location of the noxious stimulus. This neural mechanism is thought to be one way whereby the higher centers of the brain can become “confused” as to the exact location of the noxious stimulus.

Another intriguing phenomenon that may help explain pain referral is the unmasking of otherwise silent or latent synaptic connections that may occur with the activation of nociceptive sensory nerve fibers. Upon entering the brainstem, nociceptive afferent nerve fibers branch extensively to terminate on many different second order neurons that are responsible for conveying information from extensive parts of the orofacial area. Some of these synaptic connections are ineffective or latent and action potentials arriving at these synaptic connections under normal circumstances do not result in activation of the next (second-order) neuron in the afferent nerve pathway. It appears that when there is prolonged and/or intense noxious stimulation (for example, muscle trauma or repeated heavy parafunctional clenching), some of these ineffective synapses may become effective connections. Under these circumstances action potentials may be transmitted along pathways that convey information from parts of the orofacial region unrelated to the source of the noxious peripheral stimulus. The brain therefore can become confused as to the correct location of the initiating noxious stimulus.

There is a simple diagnostic test that can be done to help distinguish pain referral to a tooth as distinct from pain arising in that tooth. Clinicians can administer a diagnostic local anesthetic to produce a neural inactivation at the site where the patient complains of the pain, e.g. a tooth. If the pain being felt in the tooth is referred pain, then the pain should persist despite the local anesthetic. Such a clinical finding should alert clinicians to the possibility that the pain arises from other sites. Included in the differential diagnosis should be evaluation of muscles and joints for a possible diagnosis of temporomandibular disorder. Treatment of temporomandibular disorders involves reversible strategies including home-care remedies such as application of moist heat and pharmacotherapy.

References- Eloqayli H. Clinical Decision-Making in Chronic Spine Pain: Dilemma of Image-Based Diagnosis of Degenerative Spine and Generation Mechanisms for Nociceptive, Radicular, and Referred Pain. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:8793843. Published 2018 Dec 17. doi:10.1155/2018/8793843 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6311773

- Regional Myosin heavy chain distribution in selected paraspinal muscles. Regev GJ, Kim CW, Thacker BE, Tomiya A, Garfin SR, Ward SR, Lieber RL. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010 Jun 1; 35(13):1265-70.

- Referred muscle pain: basic and clinical findings. Clin J Pain. 2001 Mar;17(1):11-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11289083

- Pain referral patterns in the pelvis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000 May;7(2):181-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10806259

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Pain, Disability, and Chronic Illness Behavior; Osterweis M, Kleinman A, Mechanic D, editors. Pain and Disability: Clinical, Behavioral, and Public Policy Perspectives. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1987. 7, The Anatomy and Physiology of Pain. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219252

- Procacci, P., and Zoppi, M. Pathophysiology and clinical aspects of visceral and referred pain. Pain, Supplement 1:S7, 1981

- Milne, R.J., Forman, R.D., Giesler, G.J., Jr., and Willis, W.D. Convergence of cutaneous and pelvic visceral nociceptive inputs onto primate spinothalamic neurons. Pain 11:163-183, 1981

- Referred pain. J Appl Oral Sci. 2009;17(6):i. doi:10.1590/S1678-77572009000600001 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4327510