Shy Drager syndrome

Shy Drager syndrome is now called multiple system atrophy, is a rare, degenerative neurological disorder affecting your body’s involuntary (autonomic) functions, including blood pressure, breathing, bladder function and muscle control. The autonomic nervous system controls body functions that are mostly involuntary, such as regulation of blood pressure. The most frequent autonomic symptoms associated with Shy Drager syndrome are a sudden drop in blood pressure upon standing (orthostatic hypotension), urinary difficulties, and erectile dysfunction in men.

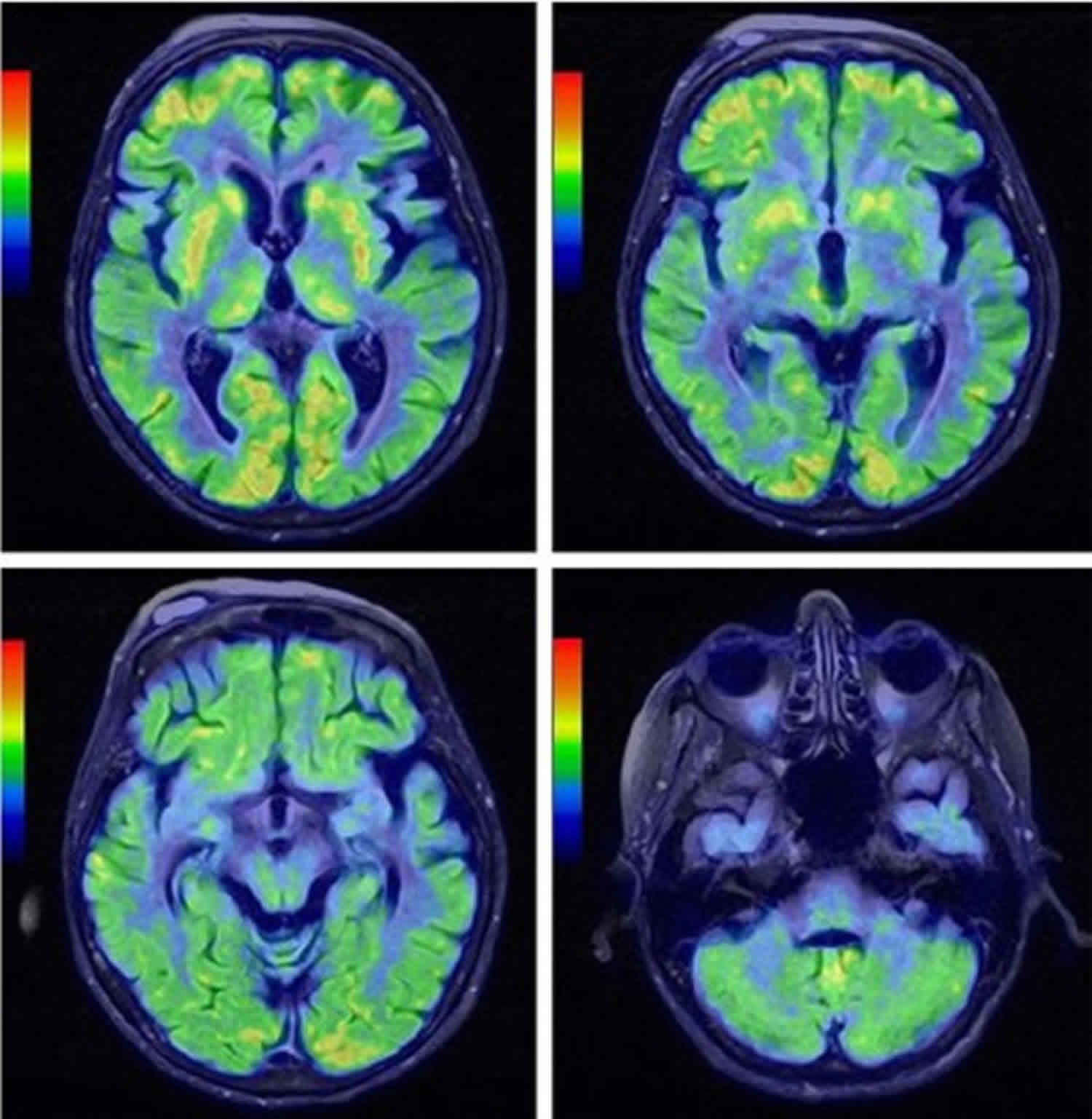

Shy Drager syndrome causes deterioration and shrinkage (atrophy) of portions of your brain (cerebellum, basal ganglia and brainstem) that regulate internal body functions, digestion and motor control.

Under a microscope, the damaged brain tissue of people with Shy Drager syndrome shows nerve cells (neurons) that contain an abnormal amount of a protein called alpha-synuclein. Some research suggests that this protein may be overexpressed in multiple system atrophy.

Shy Drager syndrome or multiple system atrophy has a prevalence of 2 to 5 per 100,000 people 1.

Researchers have described two major types of Shy Drager syndrome or multiple system atrophy, which are distinguished by their major signs and symptoms at the time of diagnosis 2.

- The parkinsonian type (MSA-P), which have Parkinson disease-like symptoms or parkinsonism, such as moving slowly (bradykinesia), stiffness or muscle rigidity, tremors, and an inability to hold the body upright and balanced (postural instability), coordination, and autonomic nervous system dysfunction.

- The cerebellar type (MSA-C), with primary symptoms of cerebellar ataxia (cerebellum is the part of the brain that is responsible for movement coordination) such as problems with balance and coordination, difficulty swallowing and speaking (dysarthria), and abnormal eye movements

Shy Drager syndrome usually occurs in older adults; on average, signs and symptoms appear around age 55. Shy Drager syndrome worsens with time and eventually leads to death and affected individuals survive an average of 10 years after the signs and symptoms first appear. However, the survival rate with Shy Drager syndrome varies widely. Occasionally, people can live for 15 years or longer with the disease. Death is often due to respiratory problems.

Treatment may include medication, physical, occupational, and speech therapy, and nutritional support, but there is no cure for Shy Drager syndrome, and there is no known way to prevent the disease from getting worse. The goal of treatment is to control symptoms 3. Most people with Shy Drager syndrome survive between 6-15 years after symptoms first begin 4.

Shy Drager syndrome causes

Shy Drager syndrome or multiple system atrophy is a complex condition that is likely caused by the interaction of multiple genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. Some of these factors have been identified, but many remain unknown.

Changes in several genes are being studied as possible risk factors for Shy Drager syndrome. The genetic risk factors with the most evidence are variants in the SNCA and COQ2 genes. The SNCA gene provides instructions for making a protein called alpha-synuclein, which is abundant in normal brain cells but whose function is unknown. Studies suggest that several common variations in the SNCA gene are associated with an increased risk of Shy Drager syndrome in people of European descent. It is unclear whether these variations also affect disease risk in other populations. The COQ2 gene provides instructions for making a protein called coenzyme Q2. This enzyme carries out one step in the production of a molecule called coenzyme Q10, which has a critical role in energy production within cells. Variations in the COQ2 gene have been associated with Shy Drager syndrome in people of Japanese descent, but this association has not been found in other populations. It is unclear how changes in the SNCA or COQ2 gene increase the risk of developing Shy Drager syndrome.

Researchers have also examined environmental factors that could contribute to the risk of Shy Drager syndrome. Initial studies suggested that exposure to solvents, certain types of plastic or metal, and other potential toxins might be associated with the condition. However, these associations have not been confirmed.

In all cases, Shy Drager syndrome is characterized by clumps of abnormal alpha-synuclein protein that, for unknown reasons, build up in cells in many parts of the brain and spinal cord. Over time, these clumps (which are known as inclusions) damage cells in parts of the nervous system that control movement, balance and coordination, and autonomic functioning. The progressive loss of cells in these regions underlies the major features of Shy Drager syndrome.

Shy Drager syndrome symptoms

Shy Drager syndrome or multiple system atrophy affects many parts of your body. Most patients with Shy Drager syndrome or multiple system atrophy develop the disease when they are older than 40 years (average 52-55 years), and they experience fast progression. Usually autonomic and/or urinary dysfunction develops first. Patients with Shy Drager syndrome may have parkinsonian symptoms with poor or nonsustained response to levodopa therapy. Only 30% of MSA-P patients have an initial transient improvement. About 90% of patients are nonresponsive to long-term levodopa therapy.

Typically, 60% of patients experience objective decline in motor function within 1 year. Motor impairment can be caused by cerebellar dysfunction. Corticospinal tract dysfunction also can occur but is not often a major symptomatic feature of Shy Drager syndrome 5.

Autonomic and/or urinary dysfunction

Autonomic symptoms are the initial feature in 41-74% of patients with Shy Drager syndrome; these symptoms ultimately develop in 97% of patients. Genitourinary dysfunction is the most frequent initial complaint in women, and erectile dysfunction is the most frequent initial complaint in men.

Severe orthostatic hypotension

Severe orthostatic hypotension is defined as a reduction in systolic blood pressure of at least 30mm Hg or in diastolic blood pressure of at least 15mm Hg, within 3 minutes of standing from a previous 3-minute interval in the recumbent position. This form of hypotension is common in Shy Drager syndrome, being present in at least 68% of patients. Most patients do not respond with an adequate heart rate increase. The definition of severe orthostatic blood pressure fall as a diagnostic criterion for Shy Drager syndrome is stricter than the definition of orthostatic hypotension as a physical finding as defined by the American Autonomic Society 6.

Symptoms associated with orthostatic hypotension include the following:

- Light-headedness

- Dizziness

- Dimming of vision

- Head, neck, or shoulder pain

- Altered mentation

- Weakness – Especially of the legs

- Fatigue

- Yawning

- Slurred speech

- Syncope

Some patients have fewer orthostatic symptoms. In 51% of patients with Shy Drager syndrome, syncope is reported at least once. In 18% of patients with severe hypotension, more than 1 syncopal episode is documented. Because of dysautonomia-mediated baroreflex impairment and consequent debuffering, patients respond in an exaggerated fashion to drugs that raise or lower their blood pressure.

Orthostatic hypotension must be distinguished from postural tachycardia syndrome, which is defined as an increase in heart rate of greater than 30 beats per minute (bpm) and maintained blood pressure (absence of orthostatic hypotension).

Postprandial hypotension

Patients are also susceptible to postprandial hypotension. Altered venous capacitance and baroreflex dysfunction have been reported as a cause 7.

Supine hypertension

Approximately 60% of patients with Shy Drager syndrome have orthostatic hypotension and supine hypertension. The supine hypertension is sometimes severe (>190/110mm Hg) and complicates the treatment of orthostatic hypotension.

Parkinsonism

This is the most common type of Shy Drager syndrome. The signs and symptoms are similar to those of Parkinson’s disease, such as:

- Rigid muscles

- Difficulty bending your arms and legs

- Slow movement (bradykinesia)

- Tremors (rare in Shy Drager syndrome compared with classic Parkinson’s disease)

- Problems with posture and balance

Parkinsonism can be the initial feature in 46% of patients with Shy Drager syndrome with predominant parkinsonism (MSA-P); it ultimately develops in 91% of these MSA-P patients. Although akinesia and rigidity predominate, tremor is present at rest in 29% of patients; however, a classic pill-rolling parkinsonian rest tremor is recorded in only 8-9%. Patients with MSA-P have a poor response to levodopa.

About 28-29% of patients have a good or even excellent levodopa response early in their disease. However, only 13% maintain this response. Patients with early onset (at < 49 years) MSA-P tend to have a good levodopa response.

Patients sometimes complain of stiffness, clumsiness, or a change in their handwriting at the onset of the disease.

Cerebellar dysfunction

Cerebellar symptoms or signs are the only initial feature in 5% of Shy Drager syndrome patients. Shy Drager syndrome with cerebellar features (MSA-C) most commonly causes gait and limb ataxia; tremor, pyramidal signs, and myoclonus are less common findings.

The main signs and symptoms are problems with muscle coordination (ataxia), but others may include:

- Impaired movement and coordination, such as unsteady gait and loss of balance

- Slurred, slow or low-volume speech (dysarthria)

- Visual disturbances, such as blurred or double vision and difficulty focusing your eyes

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) or chewing

Additional symptoms

- Bowel dysfunction

- Constipation

- Sweating abnormalities

- Reduced production of sweat, tears and saliva

- Heat intolerance due to reduced sweating

- Impaired body temperature control, often causing cold hands or feet

- Sleep disorders

- Agitated sleep due to “acting out” dreams

- Abnormal breathing at night

- Sexual dysfunction

- Inability to achieve or maintain an erection (impotence)

- Loss of libido

- Cardiovascular problems

- Irregular heartbeat

- Psychiatric problems

- Difficulty controlling emotions, such as laughing or crying inappropriately

Other symptoms of Shy Drager syndrome are based on mixed dysfunction. When the disorder results in nonautonomic features, imbalance caused by cerebellar or extrapyramidal abnormalities is the most common feature.

If the cerebellar, extrapyramidal, and pyramidal systems are involved, the movement disorder is usually the most profound disability.

Vocal cord paralysis may lead to hoarseness and stridor. A neurogenic and obstructive mixed form of sleep apnea can occur.

Shy Drager syndrome complications

The progression of Shy Drager syndrome varies, but the condition does not go into remission. As the disorder progresses, daily activities become increasingly difficult.

Possible complications include:

- Breathing abnormalities during sleep

- Injuries from falls caused by poor balance or fainting

- Progressive immobility that can lead to secondary problems such as a breakdown of your skin

- Loss of ability to care for yourself in day-to-day activities

- Vocal cord paralysis, which makes speech and breathing difficult

- Increased difficulty swallowing

Shy Drager syndrome diagnosis

Diagnosing Shy Drager syndrome or multiple system atrophy can be challenging. Certain signs and symptoms of Shy Drager syndrome — such as muscle rigidity and unsteady gait — also occur with other disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, making the diagnosis more difficult. The clinical examination, with various autonomic tests and imaging studies, can help your doctor determine whether the diagnosis is probable Shy Drager syndrome or possible Shy Drager syndrome.

As a result, some people are never properly diagnosed. However, doctors are increasingly aware of the disease and more likely to use physical examination and autonomic tests to determine if Shy Drager syndrome is the most likely cause of your symptoms.

If your doctor suspects multiple system atrophy, he or she will obtain a medical history, perform a physical examination, and possibly order blood tests and brain-imaging scans, such as an MRI, to determine whether brain lesions or shrinkage (atrophy) is present that may be triggering symptoms.

You may receive a referral to a neurologist or other specialist for specific evaluations that can help in making the diagnosis.

Tilt table test

This test can help determine if you have a problem with blood pressure control. In this procedure, you’re placed on a motorized table and strapped in place. Then the table is tilted upward so that your body is nearly vertical.

During the test, your blood pressure and heart rate are monitored. The findings can document both the extent of blood pressure irregularities and whether they occur with a change in physical position.

Tests to assess autonomic functions

Doctors may order other tests to assess your body’s involuntary functions, including:

- Blood pressure measurement, lying down and standing

- A sweat test to evaluate perspiration

- Tests to assess your bladder and bowel function

- Electrocardiogram to track the electrical signals of your heart

If you have sleep irregularities, especially interrupted breathing or snoring, your doctor may recommend an evaluation in a sleep laboratory. This can help diagnose an underlying and treatable sleep disorder, such as sleep apnea.

Shy Drager syndrome treatment

There’s no cure for Shy Drager syndrome or multiple system atrophy. Managing the disease involves treating signs and symptoms to make you as comfortable as possible and to maintain your body functions.

To treat specific signs and symptoms, your doctor may recommend:

- Medications to raise blood pressure. The corticosteroid fludrocortisone and other medications can increase your blood pressure by helping your body retain more salt and water.

- The drug pyridostigmine (Mestinon) can raise your standing blood pressure without increasing your blood pressure while you’re lying down.

- Midodrine can raise your blood pressure quickly; however, it needs to be taken carefully as it can elevate pressure while lying down so people should not lay flat for four hours after taking the medication.

- The FDA has approved droxidopa (Northera) for treating orthostatic hypotension. Droxidopa is a synthetic amino precursor prodrug and is converted to norepinephrine 8. The most common side effects of droxidopa include headache, dizziness and nausea.

- Medications to reduce Parkinson’s disease-like signs and symptoms. Certain medications used to treat Parkinson’s disease, such as combined levodopa and carbidopa (Duopa, Sinemet), can be used to reduce Parkinson’s disease-like signs and symptoms, such as stiffness, balance problems and slowness of movement. These medications can also improve overall well-being. However, not everyone with Shy Drager syndrome responds to Parkinson’s drugs. They may also become less effective after a few years.

- Pacemaker. Your doctor may advise implanting a heart pacemaker to keep your heart beating at a rapid pace, which can increase your blood pressure.

- Impotence drugs. Impotence can be treated with a variety of drugs, such as sildenafil (Revatio, Viagra), designed to manage erectile dysfunction.

- Steps to manage swallowing and breathing difficulties. If you have difficulty swallowing, try eating softer foods. If swallowing or breathing becomes increasingly problematic, you may need a surgically inserted feeding or breathing tube. In advanced Shy Drager syndrome, you may require a tube (gastrostomy tube) that delivers food directly into your stomach.

- Bladder care. If you’re experiencing bladder control problems, medications can help in the earlier stages. Eventually, when the disease becomes advanced, you may need to have a soft tube (catheter) inserted permanently to allow you to drain your bladder.

- Constipation. A high-fiber diet, bulk laxative, lactulose, and suppositories can prevent constipation.

- Falls. As the disease progresses, the risk of falls increases; proper gait instruction and precautions are critical to prevent falls and resultant injury

- Physical therapy. A physical therapist can help you maintain as much of your motor and muscle capacity as possible as the disorder progresses.

- Speech therapy. A speech-language pathologist can help you improve or maintain your speech.

Orthostatic hypotension

The earliest symptom that brings patients to medical attention usually is orthostatic hypotension. Orthostatic hypotension leads to curtailing of physical activity, with all of the problems of deconditioning that consequently occur. Without an adequate upright blood pressure, keeping patients active and on an exercise regimen is extremely difficult; therefore, management of orthostatic hypotension is one of the major tasks in the treatment of patients with Shy Drager syndrome.

Mechanical maneuvers, such as leg-crossing, squatting, abdominal compression, bending forward, and placing 1 foot on a chair, can be effective in preventing episodes of orthostatic hypotension. Wearing an external support garment that comes to the waist improves venous return and preload to the heart during standing but loses effectiveness if the patient also wears it while supine. Increased salt and fluid intake and tilted sleeping with the head elevated increase the circulatory plasma volume.

Water is a uniquely powerful pressor agent in the management of orthostatic hypotension in patients with Shy Drager syndrome. It acts by increasing sympathetic activity. On average, 16 ounces of water will raise blood pressure about 30 mm Hg. Patients may understandably be skeptical that something so commonplace could help raise their blood pressure, so it does require patient education. No other beverage (not juice or coffee or even Gatorade) is as good as a pressor agent as water in patients with autonomic dysfunction. Its major limitations are a short (1-hour) half-life and increased urination (inconvenient when autonomic impairment makes urination difficult).

Patients should drink 16 ounces of water on awakening each morning, even before they get out of bed. Patients should learn to use water prophylactically; they will be able to do much more in the hour after ingesting water than at other times. A repeat dosing midmorning or at lunch and at midafternoon may give the patient additional capacity for activity during this part of the day. Conversely, since patients with autonomic failure commonly have supine hypertension, we discourage them from drinking large amounts of water within the 2 hours prior to bedtime, although we allow them to drink when they are thirsty.

Postprandial hypotension

Small, frequent meals attenuate blood pressure drop after eating. Intake of water half an hour before meals or drinking coffee can counteract postprandial hypotension.

Supine hypertension

The management of patients with orthostatic hypotension and supine hypertension can be challenging, but adequate blood pressure control is often achieved with the following treatment strategy:

- Use of over-the-counter medication with pressor effects

- Avoidance of fluid intake at bedtime

- Not using elastic stockings when supine

- Not using pressor agents before bedtime

- Raising the head of the bed 6-9 inches

- Resting on a semirecumbent chair with feet on the floor during the day

- Snacking before bedtime

Adequate blood pressure control is often achieved by combining the nonpharmacologic approach, with the following medications:

- Nitrates, transdermal nitroglycerin (0.1–0.2 mg/h)

- Hydralazine (50 mg)

- Nifedipine; short-acting calcium blocker (10-30 mg)

- Clonidine (0.1 mg), early in the evening 9.

Diet

An essentially normal diet is recommended, with the following guidelines:

- Increased salt and fluid intake maintains plasma volume

- Small, frequent meals may help patients for whom postprandial hypotension is a significant problem

- A high-fiber diet, bulk laxatives, and suppositories prevent constipation

Activity

Exercise of muscles of the lower extremities and abdomen, water aerobics at hip level (not swimming, as it causes polyuria), and postural training, in combination with drug therapy, are useful.

Inpatient evaluation and tailoring of therapy are often important. However, if patients are restricted to bedrest, their functional mobility can decrease rapidly. Therefore, initiate physical therapy if the patient must remain in the hospital for longer than 2 days.

Shy Drager syndrome prognosis

Patients with Shy Drager syndrome have a poor prognosis. The disease progresses rapidly. Median survivals of 6.2-9.5 years from the onset of first symptoms have been reported since the late 20th century 10. No current therapeutic modality reverses or halts the progress of this disease. MSA-P (Parkinson disease-like) and MSA-C (cerebellar type) have the same survival times, but MSA-P (Parkinson disease-like) shows more rapid dysfunctional progression.

An older age at onset has been associated with shorter duration of survival in Shy Drager syndrome. The overall striatonigral cell loss is correlated with the severity of disease at the time of death.

Bronchopneumonia (48%) and sudden death (21%) are common terminal conditions in Shy Drager syndrome. Urinary dysfunction in Shy Drager syndrome often leads to lower urinary tract infections (UTIs); more than 50% of patients with Shy Drager syndrome suffer from recurrent lower UTIs and a significant number die of related complications 11.

References- Multiple system atrophy. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/multiple-system-atrophy

- Multiple System Atrophy. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1154583-overview

- Multiple system atrophy: Clinical features and diagnosis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/multiple-system-atrophy-clinical-features-and-diagnosis

- Multiple system atrophy: Prognosis and treatment. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/multiple-system-atrophy-prognosis-and-treatment

- Köllensperger M, Stampfer-Kountchev M, Seppi K, Geser F, Frick C, Del Sorbo F. Progression of dysautonomia in multiple system atrophy: a prospective study of self-perceived impairment. Eur J Neurol. 2007 Jan. 14(1):66-72.

- Lahrmann H, Cortelli P, Hilz M. EFNS guidelines on the diagnosis and management of orthostatic hypotension. Eur J Neurol. 2006 Sep. 13(9):930-6.

- Takamori M, Hirayama M, Kobayashi R. Altered venous capacitance as a cause of postprandial hypotension in multiple system atrophy. Clin Auton Res. 2007 Feb. 17(1):20-5.

- Biaggioni I. New developments in the management of neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014 Nov. 16(11):542.

- Shibao C, Gamboa A, Abraham R. Clonidine for the treatment of supine hypertension and pressure natriuresis in autonomic failure. Hypertension. 2006 Mar. 47(3):522-6.

- Multiple System Atrophy Prognosis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1154583-overview#a7

- Papatsoris AG, Papapetropoulos S, Singer C, Deliveliotis C. Urinary and erectile dysfunction in multiple system atrophy (MSA). Neurourol Urodyn. 2008. 27(1):22-7.