Sleep debt

Sleep debt also known as sleep deficit, describes the cumulative effect of a person not having sufficient sleep. Sleep debt is the difference between the amount of sleep you should be getting and the amount you actually get. Sleep debt is a measure of sleep adequacy calculated by subtracting the average duration of sleep achieved from the duration of sleep needed to feel rested 1. Sleep debt is thought to accumulate over multiple nights of insufficient sleep and can have negative consequences over time 2. With polysomnography, duration of sleep achieved can be determined objectively, but for this study, both of these values were subjective. Duration of sleep needed to feel rested is a value that is likely different for everyone. A 2005 survey by the National Sleep Foundation reports that, on average, Americans sleep 6.9 hours per night 6.8 hours during the week and 7.4 hours on the weekends. Generally, experts recommend eight hours of sleep per night, although some people may require only six hours of sleep while others need ten. That means on average, you’re losing one hour of sleep each night—more than two full weeks of slumber every year. It’s important for people to understand that a large sleep debt can well lead to physical and/or mental fatigue. Sleep debt is associated with increasing age 1.

The two known kinds of sleep debt are the results of total sleep deprivation and the results of partial sleep deprivation. Total sleep deprivation is when a person is kept awake for a minimum of 24 hours, while partial sleep deprivation occurs when either a person or lab animal has limited sleep for several days or even weeks. The specifics of sleep debt are still being debated by the scientific community; however, sleep debt is not considered to be a disorder.

Sleep debt is a pervasive problem that increases in frequency as individuals age. As the proportion of geriatric persons increases in the population in the U.S. and worldwide, the prevalence of sleep disorders will increase. Other causes of sleep loss, such as obesity, which leads to obstructive sleep apnea, are also on the rise 3. Studies have found that sleep loss is more common than previously thought. Estimates are that 50 to 70 million Americans suffer from some form of sleep loss 4. The drivers behind the recently increased prevalence of sleep loss include several broad societal changes, including working longer hours, shift work, and having greater access to television and the internet. Adults today are sleeping less to get more work done and staying up late to watch TV or use the Internet. A recent study found in people ages 25 to 45 years old, 20% were consistently sleeping 90 minutes less than was needed to maintain good health 5. The problem of inadequate sleep is likely to increase due to society’s 24/7 nature, with activities to do at all hours and increased access to night time use of computers, mobile phones, and television. Studies have found that there has been a decline in the amount of sleep of up to 18 minutes per night over the last three decades 6. Epidemiological studies may inaccurately depict this problem as data is collected by self-report methods, which do not differentiate between time asleep and time in bed. Polysomnography is accurate but is expensive and time-consuming to utilize in extensive epidemiological studies. A new, cheaper method to collect data on sleeping habits involves the use of actigraphy 7.

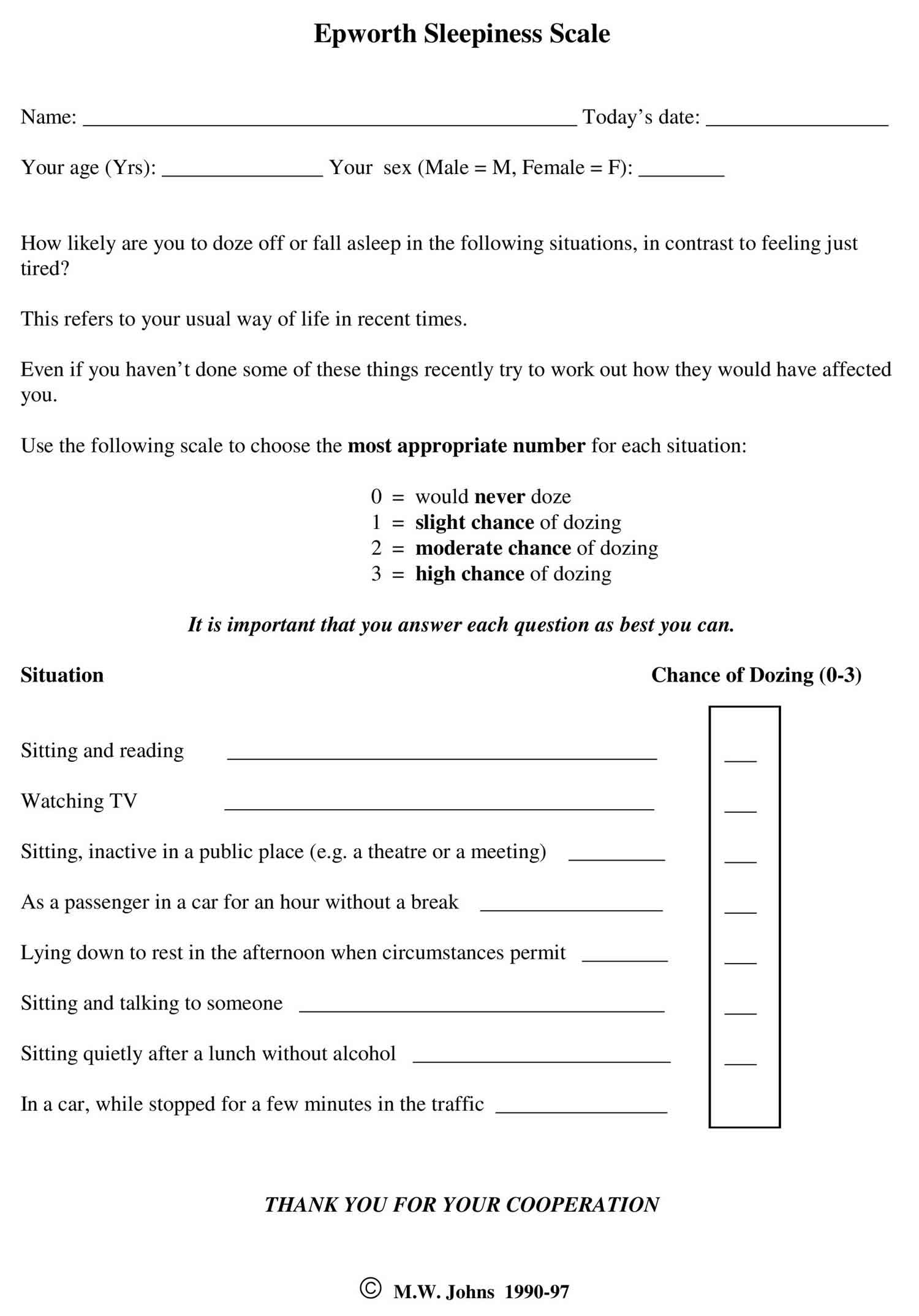

Sleep debt has been tested in a number of studies using the Sleep Onset Latency Test, which is a test designed to determine how quickly and easily a person can fall asleep. It’s known as a Multiple Sleep Latency Test when the test is done several times during a period of one day. In this test the subject is told to sleep, and is then awakened after determining how long it took the subject to fall asleep. Another useful tool for screening potential sleep debt is the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). Epworth Sleepiness Scale is a self-administered questionnaire with 8 questions. The questionnaire asks the subject to rate his or her probability of falling asleep on a scale of increasing probability from 0 to 3 (0 = no chance of dozing 1 = slight chance of dozing 2 = moderate chance of dozing 3 = high chance of dozing) for eight different situations that most people engage in during their daily lives, though not necessarily every day. The scores for the eight questions are added together to obtain a single number. A number in the 0–9 range is considered to be normal while a number in the 10–24 range indicates that expert medical advice should be sought. For instance, scores of 11-15 are shown to indicate the possibility of mild to moderate sleep apnea, where a score of 16 and above indicates the possibility of severe sleep apnea or narcolepsy. Certain questions in the scale were shown to be better predictors of specific sleep disorders, though further tests may be required to provide an accurate diagnosis.

Another interesting study conducted in January 2007 at the Washington University in Saint Louis suggests that saliva testing of the enzyme amylase could be an indicator of sleep debt, because the activity of amylase increases in correlation with the length of time that the subject has been sleep deprived. Wakefulness can be controlled by the protein orexin, while important connections have been discovered between orexin, sleep debt, and amyloid beta. The suggestion here is that the development of Alzheimer’s could hypothetically be the result of excessive periods of wakefulness, or chronic sleep debt.

Figure 1. Epworth Sleepiness Scale

Chronic sleep debt

Chronic sleep deprivation has significant adverse effects on health and overall quality of life. Chronically sleep-deprived individuals had significantly lower reported markers of quality of life on a 36-item survey 8. The survey looked at areas one’s ability to function throughout the day, health problems, perception of pain, the general perception of one’s health & vitality, social functioning, and mental health.

Interestingly, many conditions that are commonly comorbid with sleep deprivation are associated with similar physiological states. Chronic sleep deprivation is associated with elevated cortisol and decreased testosterone levels. Testosterone is known to enhance the function of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and serotonin systems in the brain. This reduced function provides one possible causal link between two of the most commonly associated psychiatric disorders, depression, and anxiety. Also, elevated serum cortisol levels have correlations with depression, anxiety, hypertension, obesity, and diabetes type II. Chronic sleep deprivation correlates with increased inflammatory markers, which is associated with all the above-mentioned comorbid conditions and psychosis.

It is essential to realize that the body has many of the same physiological markers in chronic sleep deprivation as it does with its many comorbid conditions. Many of these physiological states provide the causal link between sleep deprivation and these other psychiatric and medical conditions. This cause and effect relationships are reciprocal, making chronic sleep deprivation a potential cause and result of these other conditions. It is of paramount importance to ensure a patient is getting adequate quality sleep when treating these conditions.

Sleep debt causes

Sleep debt has many causes and is generally multifactorial. Common contributing causes of sleep loss are sleep apnea, insomnia, restless leg syndrome, parasomnias, mood disturbances, psychosis, and other psychiatric, neurological and medical conditions 9. When assessing the cause(s) of sleep loss, it is essential to address any of these underlying factors directly. Providers should not treat symptoms if they identify an underlying treatable cause. If the provider is unable to identify any contributing factors, the default diagnoses are primary insomnia. Primary insomnia is most common in elderly populations. As people age, the sleep architecture changes; delta-wave (or deep) sleep decrease, and the proportion of time spent in lighter sleep increases; this results in increased sleep disruptions 8. The duration of sleep also decreases with age. Comorbid medical conditions can be both the cause and the effect of chronic sleep loss. For instance, a patient can develop obesity, which results in obstructive sleep apnea. The lack of quality sleep then leads to increased serum cortisol levels, which facilitates further weight gain.

Common causes of sleep debt:

- Inadequate sleep hygiene.

- Sleep disorders that interfere with the brain’s ability to stay awake, including narcolepsy and primary hypersomnia.

- Insufficient total sleep time.

- Distractions during sleep from a bed partner. There is data to suggest that bed partner snoring can cause disruption to sleep. A snoring mouthpiece could stop the snore sounds.

Sleep debt symptoms

The most common symptom of sleep loss is excessive daytime sleepiness. Also, patients can display depressed mood, poor focus, and impaired memory. Lack of sleep can also exacerbate psychiatric and medical conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, hypertension, depression, anxiety, etc. Lack of sleep will impair executive functions 10. Muscle fascia tears, hernias, and other problems usually associated with physical overexertion have been reported in extreme cases of sleep deprivation. At the extreme end of the scale, sleep deprivation can mimic psychosis, where distorted perceptions can lead to inappropriate behavioral and emotional responses 11.

Depression

Interestingly, there have been studies that show sleep restriction might have potential when it comes to treating depression. Scientists know that people suffering from depression experience earlier incidences of REM sleep plus increased rapid eye movements; and monitoring a patient’s EEG and waking them during bouts of REM sleep appears to produce a therapeutic effect, thus alleviating symptoms of depression. When sleep deprived, up to 60% of patients show signs of immediate recovery; however, most relapse the next night. It’s believed that this effect is linked to increases in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). It’s also been shown that, in normal people, chronotype is related to the effect that sleep deprivation has on mood: following sleep deprivation, people who prefer mornings become more depressed, while those who prefer evenings show a marked improvement in their mood.

In 2014, a thorough evaluation of the human metabolome in sleep deprivation discovered that 27 metabolites are increased following 24 waking hours, with suggestions that tryptophan, serotonin, and taurine may be contributing to the antidepressive effect.

Weight gain or weight Loss

When rats were exposed to prolonged sleep deprivation the result was that both food intake and energy expenditure increased, resulting in a net weight loss, and ultimately leading to death. The hypothesis of this study is that when moderate chronic sleep debt goes hand-in-hand with habitual short sleep, energy expenditure and increased appetite are encouraged; and, in societies where high-calorie food is freely available the equation is tipped towards food intake rather than expenditure. Nationally representative samples used in several large studies suggest that one of the causes of the United States obesity problem could possibly be due to the corresponding decrease in the average number of hours that people sleep.

These findings indicate that the hormones that regulate appetite and glucose metabolism could be disrupted because of sleep deprivation. It appears that the association between obesity and sleep deprivation is strongest in young and middle-age adults. On the other hand, there are scientists who believe that related problems, such as sleep apnea, together with the physical discomfort of obesity, reduce a person’s likelihood of getting a good night’s sleep.

Sleep debt complications

Lack of adequate sleep can lead to many complications. Some of these complications can lead to further difficulty in getting sleep. Lack of sleep causes elevated cortisol, which can result in increased blood sugar, increased blood pressure, cravings for carbohydrates, and sugar, which leads to weight gain and other medical and psychiatric complications. The subjective experience of sleep loss can be distressing, which can exacerbate complications. The following is a non-comprehensive list of complications of sleep loss:

- Diabetes/insulin resistance

- Hypertension

- Obesity

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Vascular disease

- Stroke

- Myocardial infarct

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Psychosis

Sleep debt diagnosis

To diagnose your condition, your doctor may make an evaluation based on your signs and symptoms, an examination, and tests. Your doctor may refer you to a sleep specialist in a sleep center for further evaluation.

You’ll have a physical examination, and your doctor will examine the back of your throat, mouth and nose for extra tissue or abnormalities. Your doctor may measure your neck and waist circumference and check your blood pressure.

A sleep specialist may conduct additional evaluations to diagnose your condition, determine the severity of your condition and plan your treatment. The evaluation may involve overnight monitoring of your breathing and other body functions as you sleep.

It is vital to assess a person’s quality and quantity of sleep. Seven to eight hours and nine hours of sleep are generally ideal for adults and adolescents, respectively. Less sleep correlates with obesity, diabetes & impaired glucose tolerance, cardiovascular disease & hypertension, anxiety and depressive symptoms, and alcohol use 8. The presence of these ailments could serve as indicators that a patient may have an impaired quality of sleep. As a rule of thumb, the sicker the patient, the less likely it is that the patient sleeps well.

When taking a history, essential questions to ask to assess a patient’s sleep are:

- Do you have trouble falling asleep? Staying asleep? Do you feel tired upon waking from sleep?

- If the patient answers affirmatively to any of these questions, follow up with:

- Do these problems with sleep occur despite adequate time and opportunity for rest?

- Is the sleep difficulty impairing your functioning during the day?

- Do you feel distressed from the lack of quality sleep?

It is also essential to make an inquiry regarding the severity and frequency of these symptoms 8. A patient who lacks adequate sleep will commonly endorse symptoms of sleep loss, such as excessive daytime sleepiness, poor concentration, fatigue, moodiness, and decreased libido, among other symptoms 12. Be sure to optimize the patient’s sleep before focusing on symptom relief. Again, correct the cause, not the symptom.

Upon determination of the poor quality of sleep, further evaluation is needed to determine potential causes of sleep loss. There will generally be more than one cause contributing to the loss of sleep.

Tests to detect sleep debt include:

- Polysomnography. During this sleep study, you’re hooked up to equipment that monitors your heart, lung and brain activity, breathing patterns, arm and leg movements, and blood oxygen levels while you sleep. You may have a full-night study, in which you’re monitored all night, or a split-night sleep study. In a split-night sleep study, you’ll be monitored during the first half of the night. If you’re diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea, staff may wake you and give you continuous positive airway pressure for the second half of the night. Polysomnography can help your doctor diagnose obstructive sleep apnea and adjust positive airway pressure therapy, if appropriate. This sleep study can also help rule out other sleep disorders that can cause excessive daytime sleepiness but require different treatments, such as leg movements during sleep (periodic limb movements) or sudden bouts of sleep during the day (narcolepsy).

- Home sleep apnea testing. Under certain circumstances, your doctor may provide you with an at-home version of polysomnography to diagnose obstructive sleep apnea. This test usually involves measurement of airflow, breathing patterns and blood oxygen levels, and possibly limb movements and snoring intensity.

Your doctor also may refer you to an ear, nose and throat doctor to rule out any anatomic blockage in your nose or throat.

Sleep debt treatment

To date, there are no formal treatment guidelines. However, there are many effective ways to treat sleep debt. The primary treatment of sleep deprivation is to increase total sleep time. Treating the cause of sleep deprivation is generally the solution to the problem. If a sleep disorder is interrupting sleep, the problem will need to be addressed in order to improve sleep duration and quality. Inadequate sleep hygiene or insufficient sleep is often a cause that needs to be addressed 13.

If obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a cause of quality sleep loss, it is best to address this with continuous positive airway pressure/power (CPAP) and/or weight loss. Ignoring the contribution of obstructive sleep apnea to the sleep disturbance and prescribing sedating sleep aids could worsen the obstructive sleep apnea and quality of sleep. It is also important to identify the symptoms the patient may be experiencing from sleep loss. The symptoms the patient suffers from should be monitored to assess treatment progress. After optimizing sleep by addressing all the contributing factors, it is crucial to re-evaluate the patient for residual symptoms. At this time, symptomatic relief can be the focus.

Treatment for sleep consists of three general approaches:

- Behavioral modification/improving sleep hygiene

- Treating causative medical and psychiatric conditions

- Pharmacotherapy

It is important to review proper sleep hygiene with the patient to eliminate behavioral habits that adversely affect sleep. As mentioned previously, many of the comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions can be contributing to the trouble with sleep. The individual treatments for all these comorbidities are beyond the scope of this article. If the first two treatment options fail to resolve the sleep difficulties, one can consider pharmacotherapy. The clinician should be judicious when using medications as sleep aids because they can have unintended adverse effects. Certain medications can worsen daytime fatigue if given at too high a dose or if the medication half-life is too long. Sedating sleep aids can also exacerbate the conditions causing poor sleep. OSA can be worsened by sleep aids that promote weight gain and further relax the muscles around the airway during rest.

If sleep debt is a result of a lifestyle that cannot be changed (e.g., shift work), the provider can address excessive daytime sleepiness by giving specific behavioral tips to help individuals stay alert. Medications that promote wakefulness, such as caffeine, modafinil, and methylphenidate, are options. Currently, modafinil is the only medication that is FDA approved for shift work sleep disorder, but not sleep debt 14.

Repaying sleep debt

The good news is that, like all debt, with some work, sleep debt can be repaid—though it won’t happen in one extended snooze marathon. Tacking on an extra hour or two of sleep a night is the way to catch up. For the chronically sleep deprived, take it easy for a few months to get back into a natural sleep pattern.

Go to bed when you are tired, and allow your body to wake you in the morning (no alarm clock allowed). You may find yourself catatonic in the beginning of the recovery cycle: Expect to bank upward of ten hours shut-eye per night. As the days pass, however, the amount of time sleeping will gradually decrease.

For recovery sleep, both the hours slept and the intensity of the sleep are important. Some of your most refreshing sleep occurs during deep sleep. Although such sleep’s true effects are still being studied, it is generally considered a restorative period for the brain. And when you sleep more hours, you allow your brain to spend more time in this rejuvenating period.

As you erase sleep debt, your body will come to rest at a sleep pattern that is specifically right for you. Sleep researchers believe that genes—although the precise ones have yet to be discovered—determine our individual sleeping patterns. That more than likely means you can’t train yourself to be a “short sleeper”—and you’re fooling yourself if you think you’ve done it. A 2003 study in the journal Sleep found that the more tired we get, the less tired we feel.

So earn back that lost sleep—and follow the dictates of your innate sleep needs. You’ll feel better.

References- Fox EC, Wang K, Aquino M, et al. Sleep debt at the community level: impact of age, sex, race/ethnicity and health. Sleep Health. 2018;4(4):317–324. doi:10.1016/j.sleh.2018.05.007 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6101976

- Estimating individual optimal sleep duration and potential sleep debt. Kitamura S, Katayose Y, Nakazaki K, Motomura Y, Oba K, Katsunuma R, Terasawa Y, Enomoto M, Moriguchi Y, Hida A, Mishima K. Sci Rep. 2016 Oct 24; 6():35812.

- Sharma SK. Wake-up call for sleep disorders in developing nations. Indian J. Med. Res. 2010 Feb;131:115-8.

- Ferrie JE, Kumari M, Salo P, Singh-Manoux A, Kivimäki M. Sleep epidemiology–a rapidly growing field. Int J Epidemiol. 2011 Dec;40(6):1431-7.

- Léger D, Roscoat Ed, Bayon V, Guignard R, Pâquereau J, Beck F. Short sleep in young adults: Insomnia or sleep debt? Prevalence and clinical description of short sleep in a representative sample of 1004 young adults from France. Sleep Med. 2011 May;12(5):454-62.

- Rowshan Ravan A, Bengtsson C, Lissner L, Lapidus L, Björkelund C. Thirty-six-year secular trends in sleep duration and sleep satisfaction, and associations with mental stress and socioeconomic factors–results of the Population Study of Women in Gothenburg, Sweden. J Sleep Res. 2010 Sep;19(3):496-503.

- Van Den Berg JF, Van Rooij FJ, Vos H, Tulen JH, Hofman A, Miedema HM, Neven AK, Tiemeier H. Disagreement between subjective and actigraphic measures of sleep duration in a population-based study of elderly persons. J Sleep Res. 2008 Sep;17(3):295-302.

- Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5 Suppl):S7–S10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1978319

- Hanson JA, Huecker MR. Sleep Deprivation. [Updated 2019 Nov 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547676

- Wilckens KA, Woo SG, Kirk AR, Erickson KI, Wheeler ME. Role of sleep continuity and total sleep time in executive function across the adult lifespan. Psychol Aging. 2014 Sep;29(3):658-65.

- Alhola P, Polo-Kantola P. Sleep deprivation: Impact on cognitive performance. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(5):553–567. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2656292

- Al-Abri MA. Sleep Deprivation and Depression: A bi-directional association. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2015 Feb;15(1):e4-6.

- Consequences of sleep deprivation. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2010;23(1):95-114. doi: 10.2478/v10001-010-0004-9. DOI:10.2478/v10001-010-0004-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20442067

- Sheng P, Hou L, Wang X, Wang X, Huang C, Yu M, Han X, Dong Y. Efficacy of modafinil on fatigue and excessive daytime sleepiness associated with neurological disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e81802