Smith Magenis syndrome

Smith-Magenis syndrome is a developmental disorder that affects many parts of the body. The major features of Smith-Magenis syndrome include mild to moderate intellectual disability, delayed speech and language skills, distinctive facial features, sleep disturbances, and behavioral problems 1.

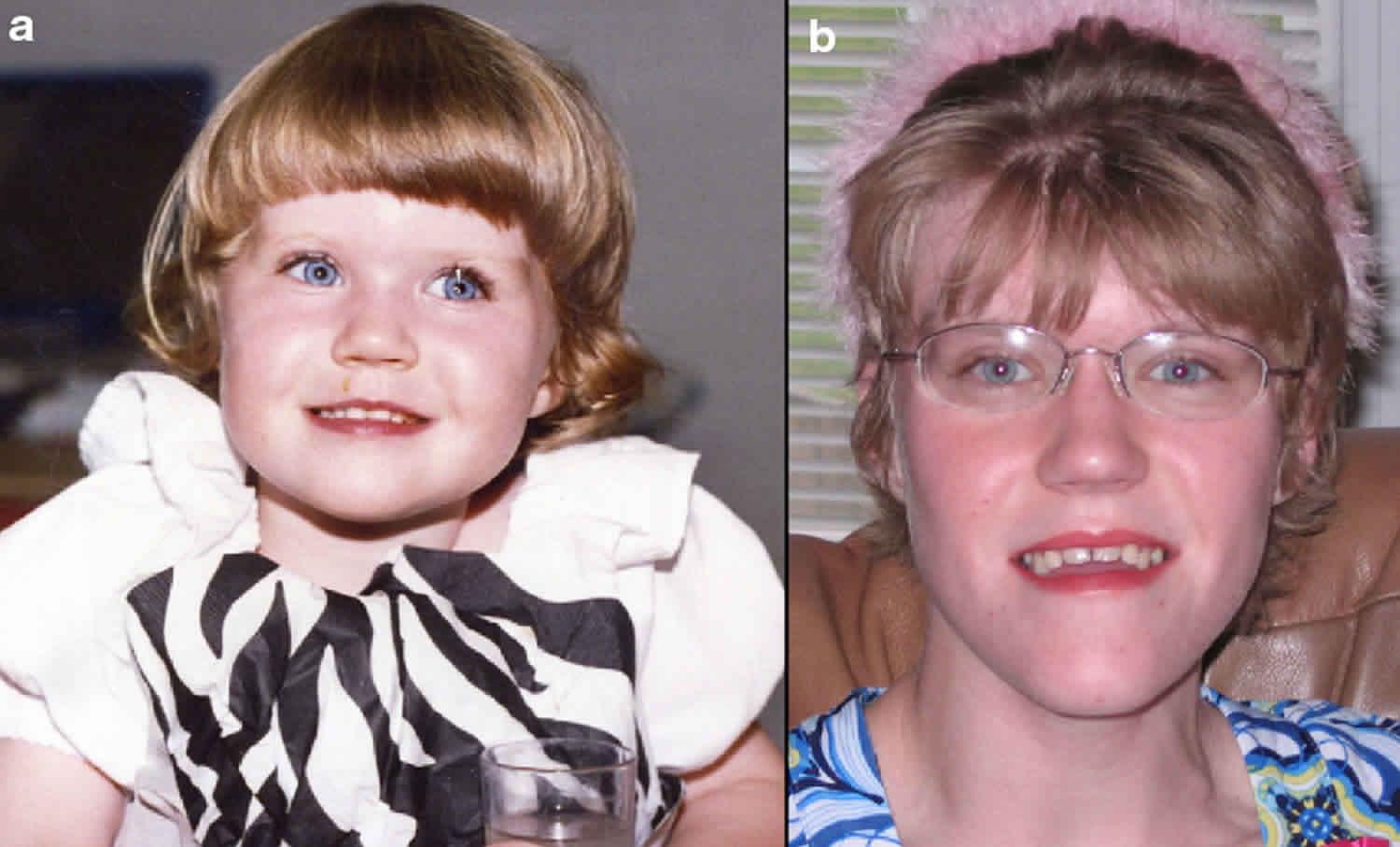

Most people with Smith-Magenis syndrome have a broad, square-shaped face with deep-set eyes, full cheeks, and a prominent lower jaw. The middle of the face and the bridge of the nose often appear flattened. The mouth tends to turn downward with a full, outward-curving upper lip. These facial differences can be subtle in early childhood, but they usually become more distinctive in later childhood and adulthood. Dental abnormalities are also common in affected individuals.

Disrupted sleep patterns are characteristic of Smith-Magenis syndrome, typically beginning early in life. Affected people may be very sleepy during the day, but they have trouble falling asleep at night and awaken several times during the night and early morning.

People with Smith-Magenis syndrome typically have affectionate, engaging personalities, but most also have behavioral problems. These include frequent temper tantrums and outbursts, aggression, anxiety, impulsiveness, and difficulty paying attention. Self-injury, including biting, hitting, head banging, and skin picking, is very common. Repetitive self-hugging is a behavioral trait that may be unique to Smith-Magenis syndrome. Some people with this condition also compulsively lick their fingers and flip pages of books and magazines (a behavior known as “lick and flip”).

Other signs and symptoms of Smith-Magenis syndrome include short stature, abnormal curvature of the spine (scoliosis), reduced sensitivity to pain and temperature, and a hoarse voice. Some people with this disorder have ear abnormalities that lead to hearing loss. Affected individuals may have eye abnormalities that cause nearsightedness (myopia) and other vision problems. Although less common, heart and kidney defects also have been reported in people with Smith-Magenis syndrome.

Smith-Magenis syndrome affects males and females in equal numbers. Smith-Magenis syndrome affects at least 1 in 25,000 individuals worldwide. Smith Magenis syndrome has been reported throughout the world and in all ethnic groups. However, researchers believe that many people with Smith-Magenis syndrome are not diagnosed, so the true prevalence may be closer to 1 in 15,000 individuals in the general population in the United States.

Most people with Smith-Magenis syndrome have a deletion of genetic material in each cell from a specific region of chromosome 17. Although this region contains multiple genes, researchers believe that the loss of one particular gene, retinoic acid-induced 1 (RAI1) gene, is responsible for most of the features of the condition. In most of these cases, the deletion is not inherited, occurring randomly during the formation of eggs or sperm, or in early fetal development 1. In rare cases, the deletion is due to a chromosomal balanced translocation in one of the parents. In about 10% of cases, Smith-Magenis syndrome is caused by a mutation in the RAI1 gene. These mutations may occur randomly, or may be inherited from a parent in an autosomal dominant manner. Treatment for Smith-Magenis syndrome depends on the symptoms present in each person 2.

If we have one child with Smith Magenis syndrome, will our other childen also have Smith Magenis syndrome?

Smith-Magenis syndrome is typically not inherited. It usually results from a genetic change that occurs during the formation of reproductive cells (eggs or sperm) or in early fetal development. Most often, people with Smith-Magenis syndrome have no history of the condition in their family and go to have other children without a genetic abnormality after a child with Smith Magenis syndrome.

What age does Smith Magenis syndrome usually present?

As it is a genetic disorder, a baby is born with Smith-Magenis syndrome. With the increased awareness and genetic analysis techniques, many babies are diagnosed at or shortly after birth, this is due to the babies presenting with facial characteristics associated with Smith Magenis syndrome or through being born with a congenital heart defect.

Sometimes a baby is not diagnosed at birth, but as they develop either the parents or professional start to notice their child has developmental delay in a variety of areas or that they have facial/statue characteristics associated with Smith Magenis syndrome and so genetic analysis is requested.

My child is having difficulty feeding, is this normal?

Infants with Smith Magenis syndrome quite often have feeding difficulties. This is caused in part by low muscles tone, lethargy and poor sucking and swallowing ability. The infant will need to be assessed by occupational therapy (OT) and speech therapy, in order to assess the oral-motor function and then oral-motor therapy to be received.

It may be that your child finds it difficult to eat anything other than soft food for quite some time. It is important to gain input from the OT, SALT and a dietician to assist with this difficulty.

My child is almost 3 and hasn’t started to talk is this normal?

Many children with Smith-Magenis syndrome experience early speech delays. However, with appropriate intervention including Speech and language therapy and the use of sign language, gestures, or a picture system, verbal speech generally develops by school age, although continued articulation difficulties can continue.

My child is showing no sign of being able to be toilet trained. Can children with Smith-Magenis syndrome be toilet trained?

Some children with Smith-Magenis syndrome do have have toileting difficulties. This can include late development of toilet training and/or night time bed wetting. However with consistent implantation of a toileting routine and input (if needed) from an incontinence nurse, in most cases, children with Smith Magenis syndrome can be toilet trained – albeit possibly later than ‘usually’ expected.

My child is 2 years old, but is not crawling or sitting up, is this normal?

Infants with Smith Magenis syndrome quite often has physical developmental delay, this is linked to the fact that many have low muscle tone in their trunk and lower body, however by the time the children are 4 or 5, most children with Smith Magenis syndrome are walking.

Can adults with Smith Magenis syndrome still lead independent lives?

Due to the varying degrees of difficulties that individuals with Smith Magenis syndrome experience, there is no set answer to this question. A few individuals are known to able to attend college and have supported part time jobs and live semi independently. However many remain living with family or in sheltered housing or residential facilities.

What is the life expectancy of individuals with Smith Magenis syndrome?

As it is a relatively ‘new’ syndrome, there isn’t a detailed knowledge of the ’average’ life expectancy. However it is known that there was an adult with Smith Magenis syndrome who lived until she was 88 years old, and there are several adults with Smith Magenis syndrome in their 40’s and 50’s. It is believed that unless there is additional medical complications, life expectancy should not be impacted upon.

Smith Magenis syndrome causes

In most people (approximately 90% cases) with Smith-Magenis syndrome, the condition results from the deletion of a small piece of chromosome 17 in each cell, which is referred to as deleted or monosomic. This deletion occurs on the short (p) arm of the chromosome at a position designated p11.2 (17q11.2). The deleted segment most often includes approximately 3.7 million DNA building blocks (base pairs), also written as 3.7 megabases (Mb). (An extra copy of this segment causes a related condition called Potocki-Lupski syndrome.) Occasionally the deletion is larger or smaller. All of the deletions affect one of the two copies of chromosome 17 in each cell.

Although the deleted region contains multiple genes, researchers believe that the loss of one particular gene, retinoic acid-induced 1 (RAI1), underlies many of the characteristic features of Smith-Magenis syndrome. All of the deletions known to cause the condition contain this gene. The retinoic acid-induced 1 (RAI1) gene provides instructions for making a protein that helps regulate the activity (expression) of other genes. Although most of the genes regulated by the RAI1 protein have not been identified, this protein appears to control the expression of several genes involved in daily (circadian) rhythms, such as the sleep-wake cycle. Studies suggest that the deletion leads to a reduced amount of RAI1 protein in cells, which disrupts the expression of genes that influence circadian rhythms. These changes may account for the sleep disturbances that occur with Smith-Magenis syndrome. It is unclear how a loss of one copy of the RAI1 gene leads to the other physical, mental, and behavioral problems associated with this condition.

A small percentage of people with Smith-Magenis syndrome have a mutation in the RAI1 gene instead of a chromosomal deletion. Although these individuals have many of the major features of the condition, they are less likely than people with a deletion to have short stature, hearing loss, and heart or kidney abnormalities. It is likely that, in people with a deletion, the loss of other genes in the deleted region accounts for these additional signs and symptoms; the role of these genes is under study.

The exact cause of the chromosomal alteration in Smith Magenis syndrome is unknown. The medical literature has indicated that virtually all documented cases appear to be due to a spontaneous (de novo) genetic change that occurs for unknown reasons.

In rare cases, Smith Magenis syndrome is the result of an error during very early embryonic development due to a chromosomal balanced translocation in one of the parents. A translocation is balanced if pieces of two or more chromosomes break off and trade places, creating an altered but balanced set of chromosomes. If a chromosomal rearrangement is balanced, it is usually harmless to the carrier. However, they may be associated with a higher risk of abnormal chromosomal development in the carrier’s offspring. In these cases, the clinical features of children may be influenced by additional imbalances of other chromosomes than 17. Chromosomal testing can determine whether a parent has a balanced translocation. In parents with a child with Smith Magenis syndrome who have a normal chromosome analysis the risk of recurrence in a future pregnancy is below 1%.

A child born to an individual with Smith Magenis syndrome is at a theoretical risk of 50% to inherit the deletion or RAI1 mutation that causes the disorder. The fertility in Smith Magenis syndrome in general is not fully understood; however, there is at least one report in the medical literature of a mother with Smith Magenis syndrome having a child with Smith Magenis syndrome.

Smith-Magenis syndrome inheritance pattern

Smith-Magenis syndrome is usually not inherited. This condition typically results from a chromosomal deletion or an RAI1 gene mutation that occurs during the formation of reproductive cells (eggs or sperm) or in early fetal development. Most people with Smith-Magenis syndrome have no history of the condition in their family.

In a small number of cases, people with Smith-Magenis syndrome have inherited the deletion or mutation from an unaffected mother who had the genetic change only in her egg cells. This phenomenon is called germline mosaicism. In germline mosaicism, some of a parent’s reproductive (germ) cells carry the RAI1 gene mutation or chromosome 17p deletion, while other germ cells do not (mosaicism). In addition, the other cells of a parent also do not have either to these chromosomal abnormalities; consequently, the parents are unaffected. However, as a result, one or more of the parent’s children may inherit the germ cell with a chromosomal abnormality, leading to the development of Smith Magenis syndrome. Germline mosaicism is suspected when apparently unaffected parents have more than one child with the disorder. The likelihood of a parent passing on a mosaic germline chromosomal abnormality to a child depends upon the percentage of the parent’s germ cells that have the abnormality versus the percentage that do not. There is no test for germline mutation or chromosome abnormality prior to pregnancy. Testing during pregnancy may be available and is best discussed with a genetic specialist.

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Smith Magenis syndrome symptoms

Smith-Magenis syndrome is a highly variable disorder. The specific symptoms present and the overall severity of the disorder can vary from one person to another. It is important to understand that affected individuals will not have all of the symptoms discussed below and that every individual case is unique. Parents should talk to the physician and medical team about their child’s specific case, associated symptoms and overall prognosis.

The major features of Smith-Magenis syndrome include mild to moderate intellectual disability, delayed speech and motor skills, distinctive facial features, sleep disturbances, skeletal and dental abnormalities, and behavioral problems.

Facial features in people with Smith Magenis syndrome may be subtle in early childhood, but usually become more apparent with age. They may include 1:

- A broad, square-shaped face with deep-set eyes, full cheeks, and a prominent lower jaw

- A “flattened” appearance to the middle of the face and the bridge of the nose

- A downward-turned mouth with a full, outward-curving upper lip

While people with Smith Magenis syndrome often have affectionate, engaging personalities, most also have behavioral problems. These may include 1:

- Frequent temper tantrums and outbursts

- Aggression

- Anxiety

- Impulsiveness

- Difficulty paying attention

- Self-injury, including biting, hitting, head-banging, and skin picking

- Repetitive self-hugging (a trait that may be unique to Smith Magenis syndrome)

- Compulsively licking the fingers and flipping pages of books (a behavior known as ‘lick and flip’)

Additional features of Smith Magenis syndrome may include short stature, scoliosis, reduced sensitivity to pain and temperature, chronic ear infections, obesity, and a hoarse voice 1.

Many individuals with Smith Magenis syndrome have distinctive facial features including a broad, square-shaped facial appearance, a prominent forehead, deep-set eyes that are farther apart than usual (hypertelorism), an upslanting palpebral (eye) fissures, a broad bridge of the nose, hair growth between the eyebrows so it appears as one long eyebrow (synophrys), a down-turned (everted; cupid bow) upper lip, a short, full-tipped nose, and underdevelopment of the middle portion of the face (midface retrusion). The head may appear disproportionately short (brachycephaly). Some affected infants may have an abnormally small jaw (micrognathia) and the facial appearance is more “cherubic” with rosy cheeks. As affected individuals age, micrognathia may change so that the lower jaw abnormally protrudes outward (relative prognathia). In general, the distinctive facial features associated with Smith Magenis syndrome progress with age. Affected individuals may also exhibit absence (agenesis) of secondary (permanent) teeth, particularly premolars, and taurodauntism, a condition characterized by enlargement of the pulp chambers and reduction of the roots of teeth; open bite posture with large tongue (macroglossia) and history of bruxism (teeth grinding) are also common.

Infants usually have diminished muscle tone (hypotonia), poor reflexes (hyporeflexia), and feeding difficulties such as poor sucking ability, which can contribute to failure to thrive. Failure to thrive is defined as the failure to grow and gain weight at a rate that would be expected based upon age and gender. Infants are generally quiet and complacent with infrequent crying and diminished vocalizations reflecting the marked early expressive speech delay. In addition, affected infants may nap for prolonged periods of time and exhibit generalized daytime lethargy. Gastroesophageal reflux is also common during infancy.

Individuals with Smith Magenis syndrome have varying degrees of cognitive ability. Many individuals exhibit mild to moderate intellectual disability. Affected individuals often exhibit delays in attaining speech and motor skills and in reaching developmental milestones (developmental delays). Expressive language is often more delayed than receptive language skills.

Specific behavioral problems (maladaptive behaviors) occur in children with Smith Magenis syndrome. A common initial sign is head banging during early childhood. Frequent upper body squeezes often described as “self-hugging” is also common. Affected children may also display impulsivity, hyperactivity and attention deficient disorder, frequent and prolonged tantrums, sudden mood changes, toilet training difficulties, disobedience, and aggressive or attention-seeking behaviors. In addition to head banging, affected children may develop other self-injurious behavior such as hand biting, face slapping, skin picking, and wrist biting. Repeated head banging can potentially cause detachment of the retina, which although a concern, is not a high risk. Older children may yank at fingernails and toenails (onychotillomania) or insert objects into body orifices (polyembolokoilamania). Affected children tend to be excitable and easily distracted. Although behavioral issues are common, many individuals tend to have endearing and engaging personalities, with great senses of humor, and facile long-term memory for faces, places and things.

Affected children may experience chronic ear infections, including repeated middle ear infections (otitis media). Hearing loss is very common, typically ranging from slight to mild in degree and showing a pattern of fluctuating and progressive hearing decline with age. Both conductive and/or sensorineural hearing loss may develop. Conductive hearing loss is most common in early childhood (under 10 years), while sensorineural hearing loss occurs more frequently at older ages (11years – adulthood). Conductive hearing loss develops when sound waves are inappropriately conducted through the external or middle ear to the inner ear, resulting in decreased sensitivity to sound. Sensorineural hearing loss develops where there is damage to the inner ear (cochlea) or the nerve pathway from inner ear to the brain. Some affected children may be abnormally sensitive to certain sounds or frequencies (hyperacusis). Frequent sinus infections (sinusitis) are also common. Eye abnormalities such as progressive nearsightedness (myopia), crossed eyes (strabismus), and unusually smallness of the cornea (microcornea) may also occur.

Affected children often have abnormalities affecting the larynx (voice box) or surrounding tissue. Laryngeal abnormalities include the formation of polyps and nodules or swelling due to fluid retention (edema). Paralysis of the vocal cords has also developed. Affected children may experience velopharyngeal insufficiency, in which the soft palate of the mouth does not close properly during speech. Oral sensorimotor dysfunction, in which affected individuals have difficulties controlling the lips, tongue and jaw muscles, may also develop and can cause tongue protrusion and frequent drooling. Due to such abnormalities, children may develop a hoarse, deep voice. These abnormalities also contribute to delays in speech development.

Excessive weight gain and obesity may be seen in adolescence and approximately 90% of children may be overweight or obese by the age of 14. Affected individuals may exhibit short stature during childhood, although height is typically within the normal range as adults. Approximately 50% of children may have unusually high levels of cholesterol in the blood (hypercholesterolemia). Chronic constipation is also a frequent complication.

The sleep disturbance that occurs in affected individuals is a chronic lifelong problem. In addition to sleep issues during infancy (generalized lethargy & “too sleepy”), affected individuals develop significant sleep disturbances from early childhood that continue into adolescence and adulthood. The sleep cycle is characterized by problems that can include difficulty falling asleep, shortened sleep cycles, an inability to enter REM sleep and frequently awaking during the night and early in the morning (5:30-6:30AM). In general, the hours of sleep are less than expected for age. As a consequence of the disrupted nighttime sleep cycle affected individuals may exhibit periods of drowsiness during the day, known as excessive daytime sleepiness or sleep debt, which remains a chronic issue. The sleep abnormalities are associated with an inverted circadian rhythm of melatonin, reported in over 90% of studied cases. A circadian rhythm sleep disorder occurs when a person’s biological clocks fails to synchronize to a normal 24-hour day. Specifically, melatonin, a normal occurring hormone, rises and falls; it rises, peaking at night and causes drowsiness. Melatonin levels lessen in the morning, reaching their lowest levels during the middle of the day. In individuals with an inverted circadian rhythm, the rising and falling of melatonin levels is reversed (daytime highs).

Skeletal malformations are common in individuals with Smith Magenis syndrome and can include front-to-back curvature of the spine (lordosis), mild-to-moderate sideways curvature of the spine (scoliosis), abnormally small hands and feet, and markedly flat or highly arched feet that can cause an unusually manner of walking (abnormal broad-based gait). In rare cases, affected children have vertebral anomalies and forearm and elbow limitations.

Less often, other symptoms or physical findings have occurred in individuals with Smith Magenis syndrome including immune system dysfunction, thyroid function abnormalities (hypothyroidism), heart (cardiac) defects, kidney (renal) and/or urinary tract malformations, cleft lip and cleft palate, and seizures. Seizure activity can occur subtly so that seizure goes unnoticed (subclinical seizures). Peripheral neuropathy, which is a general term for any disorder of the peripheral nervous system, may also occur. Peripheral neuropathy encompasses any disorder that primarily affects the nerves outside the central nervous system (i.e. brain and spinal cord). Symptoms may include a decreased sensitivity to pain commonly seen in Smith Magenis syndrome. Peripheral neuropathy is often associated with the loss of sensation or abnormal sensations such as tingling, burning, or pricking along the affected nerves, but it is unknown whether this occurs in individuals with Smith Magenis syndrome.

Smith Magenis syndrome diagnosis

A diagnosis of Smith-Magenis syndrome is based upon identification of characteristic symptoms, a detailed patient and family history, a thorough clinical evaluation and a variety of specialized genetic tests. The diagnosis of Smith Magenis syndrome is confirmed when deletion 17p11.2 (cytogenetic analysis or microarray) or RAI1 gene mutation is identified.

Clinical Testing and Workup

In the past, a specific chromosomal study known as G-band analysis, which demonstrates missing (deleted) material on chromosome 17p, was used to help obtain a diagnosis of Smith Magenis syndrome. Chromosomes may be obtained from a blood sample. During this test the chromosomes are stained so that they can be more easily seen and then are examined under a microscope where the missing segment of chromosome 17p can be detected (karyotyping). To determine the precise breakpoint, a more sensitive test known as fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) may be necessary. During a FISH exam, probes marked by a specific color of fluorescent dye are attached to a specific chromosome allowing researchers to better view that specific region of the chromosome.

A newer technique known as chromosomal microarray analysis may also be used. During this exam, a person’s DNA is compared to the DNA of a person without a chromosomal abnormality (‘control’ person). A chromosome abnormality is noted when a difference is found between the DNA samples. Chromosomal microarray analysis allows for the detection of very small changes (missing or duplicated segments) or alterations.

Molecular genetic testing can confirm a diagnosis in individuals suspected of having Smith Magenis syndrome due to a RAI1 gene mutation. Molecular genetic testing can detect mutations in the RAI1 gene known to cause Smith Magenis syndrome in specific cases, but is available only as a diagnostic service at specialized laboratories.

Smith Magenis syndrome treatment

Treatment may require the coordinated efforts of a team of specialists. Pediatricians, surgeons, cardiologists, dental specialists, speech pathologists, audiologists, ophthalmologists, psychologists, and other healthcare professionals may need to systematically and comprehensively plan and affect child’s treatment. Genetic counseling is of benefit for affected individuals and their families. Psychosocial support for the entire family is essential as well.

Treatment is symptomatic and supportive. Early intervention is important in ensuring that affected children reach their highest potential. Services that may be beneficial include special remedial education, speech/language therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and sensory integration therapy, in which certain sensory activities are undertaken in order to help regulate a child’s response to sensory stimuli. Additional medical, social and vocational services may be recommended when appropriate.

Certain medications may be used to treat behavioral problems such as attention deficit or hyperactivity. Specific medications have also been used to treat sleep disorders potentially associated with Smith Magenis syndrome. Melatonin supplementation, in order to normalize melatonin levels, taken at bedtime has shown benefit in anecdotal reports. Use of the B-blocker acebutolol in the morning to inhibit/suppress daytime melatonin secretion has shown some benefit in one French study.

Feeding difficulties require identification and appropriate therapy. Additional treatment follows standard guidelines for the specific symptom. For example, anti-seizure medications (anti-convulsants) may be used to treat seizures.

Management of Sleep Difficulties

Management of sleep disorders is likely to include behavior management, and may also include melatonin at night and possibly beta blockers or phototherapy in the morning. The timing of such interventions is likely to be very important and may vary from child to child. No formal controlled trials of these latter interventions have been conducted to date. However, they are the subject of much research interest and discussion. Referral to a specialist sleep service might be indicated.

Management of Challenging Behaviours

Consider referral to Clinical Psychology or Learning Disability services for detailed assessment and intervention. For challenging behaviors, including aggression, self injurious behaviors and impulsivity/hyperactivity, both conventional behavior therapy and pharmacological treatments should be considered, though these behaviors are often very difficult to treat.

Living with Smith Magenis syndrome

Smith-Magenis Syndrome is a complex disability. Each individual will exhibit different aspects of the characteristics and so each family with develop their own ‘coping’ strategies. It is important to get professionals involved early on to provide the family with the support needed.

Input from pediatricians, speech and language therapists, physiotherapists, educational professionals, portage, social services, child and adult mental health services etc. are all very important and a multi- agency approach is vital.

Feeding and Eating

There are several areas where difficulties with feeding may occur in people with Smith Magenis syndrome, including poor feeding in infancy, gastroesophageal reflux, textural aversion and weight gain.

- Poor feeding in infancy: This is common in in Smith Magenis syndrome and can lead to failure to thrive. It is often caused by oral motor dysfunction, with problems sucking and swallowing.

- Gastroesophageal reflux: This is where stomach acid leaks up into the esophagus which can cause discomfort after eating, pain, and difficulty with swallowing. It can also interrupt sleep, therefore, given the fact that sleep problems are associated with Smith Magenis syndrome, it is particularly important to identify and treat reflux.

- Textural aversion: Dislike of specific food textures is described, and may be an issue for people with oral motor difficulties or sensory sensitivities (see the ‘Sensory Issues’ section).

- Weight gain: The limited information available suggests that in older individuals weight gain may become an issue. It is not clear whether this is the result of over-eating (although there are reports of increased interest in food in some people, which emerges with age) or the effects of having Smith Magenis syndrome. Weight gain may also be the result of medications used; it has been suggested that medications including valproic acid, risperidone, and recent mood-stabilizing agents may not be the first choice of medication for individuals with Smith Magenis syndrome because of problems with weight gain.

Other factors that seem to be associated with weight gain include having the RAI1 mutation and gender – problems with eating /appetite and weight appear to be more commonly reported in females with Smith Magenis syndrome than in males.

What might help

- Poor feeding in infancy – Speech and language therapy (SLT) and occupational therapy (OT) evaluations should be pursued early to assess feeding difficulties, optimise oral motor abilities and develop intervention strategies.

- Textural aversion – This may be related to oral motor difficulties and require intervention from speech and language therapy. Where it is primarily a sensory issue, caregivers could try to make smooth foods before gradually making thicker foods, then introduce a few small pieces of food, and then move on to easily chewed foods.

- Gastroesophageal reflux – Be vigilant for signs of reflux; check for signs, which include frequent projectile vomiting, wheezing, bad breath and pulling legs up to stomach after feeding. Seek input from medical professionals if concerned.

- Weight gain – Encouraging a balanced diet and exercise, from an early age is a sensible approach.

Toileting

Delayed toilet training and persistent night-time wetting are particular issues in Smith Magenis syndrome (reported in up to 80% of children).

Delayed toilet training is common in children with an intellectual disability, however with consistent implementation of a toileting program, most children can become toilet trained and this is also the case for most children with Smith Magenis syndrome.

Many of the approaches that can be used are the same as that which are used with typically developing children; including rewarding children for using a potty/toilet, using a ‘fun’ potty in a favorite color or character, having regular trips to the potty which become more spaced out as children become dry, and not telling children off if there is an accident.

There is also a lot of guidance available specifically for caregivers of children with an intellectual disability, which may be useful for caregivers of children with Smith Magenis syndrome.

There may be specific health and behavioral issues associated with Smith Magenis syndrome that might affect toileting. These include difficulties communicating the need to go to the toilet, being easily distracted, delayed adaptive behaviors and constipation/urinary tract infections that children may not show clear signs of or be able to report themselves; caregivers should therefore be mindful of these difficulties when toilet-training.

What might help

- Check physical health problems – Urinary tract infections can cause episodes of wetting. Constipation may be a complicating factor in soiling. It may be necessary for a family doctor or pediatrician to examine the person to check whether they are constipated; this would need to be resolved before bowel training can commence. It is important to ensure that the person eats a balanced diet including plenty of fiber, fruit, vegetables and liquids.

- Seek input from professionals – If problems persist, seek input from professionals e.g. health visitor, family doctor, child psychologist or pediatrician, who may be able to refer on to a specialist for advice.

- Use a bedwetting alarm – Alarms can be accessed from clinics via referral from family doctors. If the person begins to wet the pad the alarm will go off, which will then cause them to wake up and stop urinating. The caregiver then takes them to the toilet and resets the alarm. Rewards may be used in conjunction with the alarm.

Dressing

Dressing and undressing requires muscle co-ordination, fine motor skills and planning. Individuals with Smith Magenis syndrome may take longer to learn these skills than their peers. A person with Smith Magenis syndrome might need help with putting on clothes and doing up buttons and shoelaces etc. As there is usually little time in the morning, caregivers may find it more convenient to dress a child with Smith Magenis syndrome themselves, to save time. However, children need to be encouraged to do these things for themselves, with caregivers slowly encouraging them to do more of the dressing independently. Some adults with Smith Magenis syndrome may still need help with dressing; around half of adults are described as needing some help with this activity.

Some caregivers also report issues with inappropriate removal of clothing in public places. This might occur because the child finds clothing uncomfortable. This could be due to sensory sensitivities, for example a label, seam or other feature of clothing might be irritating. Alternatively clothing may be too hot. It is also possible that this behaviour may be shown because it has previously been associated with a rewarding response. For example the person might have been taken away from a non-preferred activity when they previously removed their clothes (in order to re-dress them), or they may have been given attention (for example being told to put their clothes back on and perhaps helped to do this)

Teaching dressing skills

- Practice skills at convenient times – Learning to dress can be practiced at other times of the day, not just during the hectic morning period.

- Practice skills in easier situations – Teaching a child to do up buttons can sometimes be helped by encouraging him/her to practice on buttons on items of clothing that are not being worn at the time. In the same way, tying shoelaces could first be practiced on loose shoes.

- Break down tasks into smaller steps and teach one step at a time – For example, teaching putting on pair of socks, you might first put on each sock up to the ankle and teach the child to pull the sock up from the ankle. Once this step has been mastered, move on to the next stage – put the sock on his/her foot half way over the heel and teach him/her to pull the sock over the rest of the heel, then onto the instep, then just over the toes – and ask the child to pull the sock up over more of the foot at each step. Eventually you will be able to hand him/her the socks, and then leave them on the bed to be put on independently.

- Use visual prompts for each step – Pictures displaying each step of a getting dressed process e.g. tying shoelaces may also be effective.

- Provide verbal cues – For example when teaching how to do up shoelaces, a person can be helped to talk through the routine, for example by saying out loud ‘cross the laces over, pull one through, pull tight as they perform each step. In this way they learn the words and can then prompt themselves during the task.

- Buy items with easy to use fastenings – Footwear and clothing with Velcro are a good substitute for shoelaces, buttons and zips. Such items are much easier to put on and take off.

Managing clothing removal

- Ensure clothes are comfortable – Check for irritation from labels or dislike of certain types of clothes (e.g. tights). Check that the person is not too warm and dress them in light, cool clothing if necessary.

- Respond to clothing removal in a ‘low key’ manner – Limit the interaction provided (no eye contact, minimal conversation) and try to help the person to re dress and return to their previous activity as quickly as possible to reduce any potentially rewarding attention.

Ability

There is no evidence to suggest that general cognitive ability declines in adults with Smith Magenis syndrome. Furthermore, the profile of strengths and weaknesses demonstrated in the syndrome seems to be fairly consistent across the lifespan, with adults showing similar strengths in verbal comprehension compared to working memory to those shown in children. Thus, the principles of strategies that play to the strengths of younger individuals, such as visual prompts and timetables, may also be effective with older individuals, if tailored to be age-appropriate.

Mental capacity

When people with Smith Magenis syndrome are children, caregivers can make decisions on their behalf, however, when they become adults this may change. As individuals with Smith Magenis syndrome become older, issues might arise around their ability to make decisions, from whether to go to the shops to whether to have an invasive medical procedure; this is usually referred to as ‘mental capacity’.

There is legislation which governs how this ability is assessed and what steps should be taken if an individual does not have capacity to make such decisions. This can have important implications for the lives of individuals with Smith Magenis syndrome who have an intellectual disability. Where an individual is deemed to have capacity they will be able to make these decisions themselves. If a person is deemed, after assessment, not to have capacity, then a caregiver or professional (e.g. a support worker) may make decisions on their behalf, which must be in their best interests. In addition to medical issues and day-to-day life, capacity may affect issues such as planning for the future, e.g. financial decisions and decisions about living arrangements.

The implications of mental capacity will differ depending on where families are located, with different countries having different systems.

What might help?

- Engage with legislation – Caregivers or support workers should familiarize themselves with the relevant legislation regarding capacity in their location.

- Assess capacity – Caregivers or support workers should engage in an assessment of capacity where this is needed.

- Plan for the future – Caregivers or support workers should put in place any legal arrangements needed to plan for the future (e.g. wills and trusts).

Smith Magenis syndrome prognosis

Because of the highly variable nature of Smith Magenis syndrome, it is impossible to generalize about prognosis for individual cases. Some affected individuals have been able to become employed and even live semi-independently with support from family and friends. However, others require constant care and may need to live with family or in a residential facility. As stated above, parents should talk to the physician and medical team about their child’s specific case and overall prognosis.

References