What is thyroidectomy

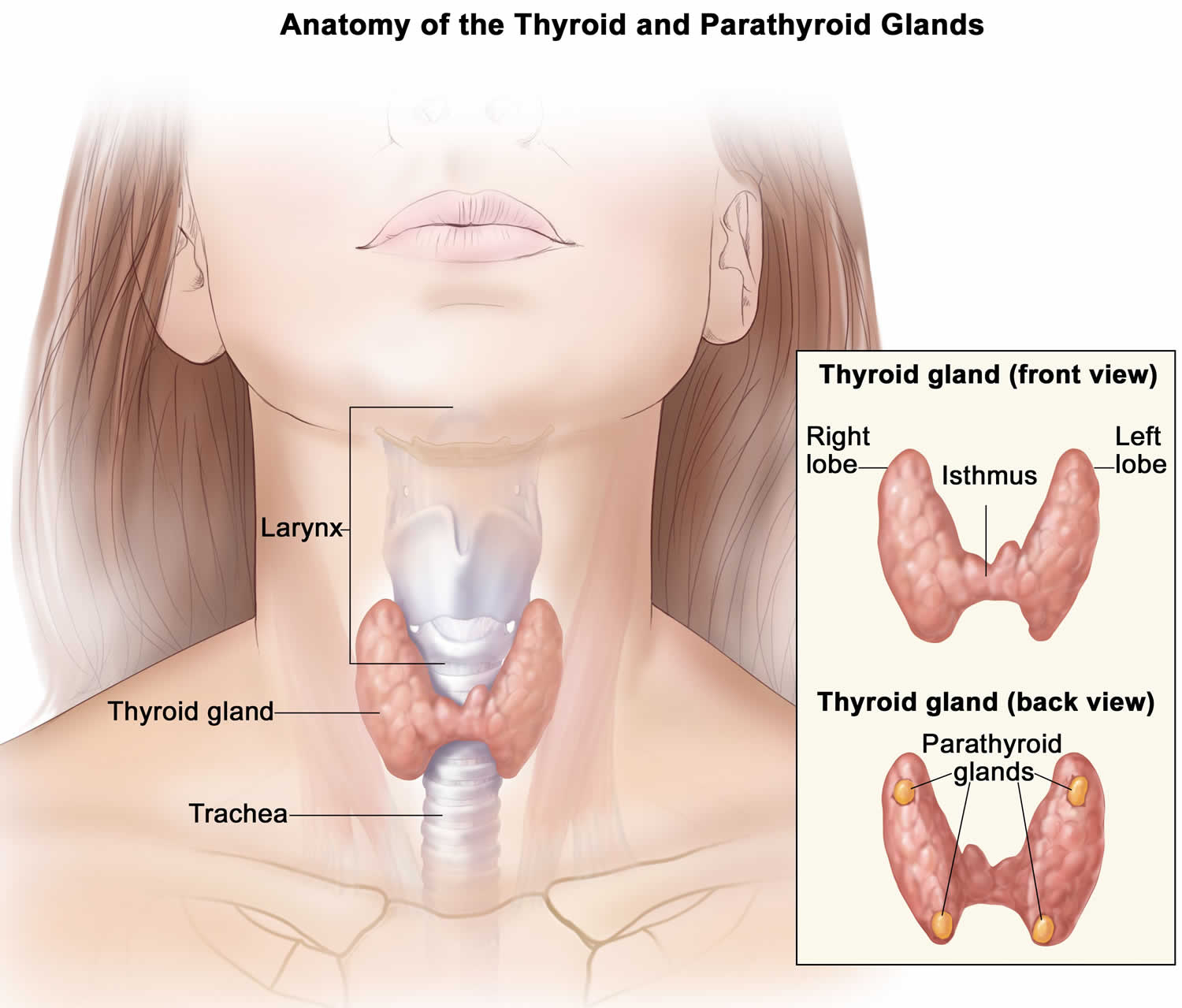

Thyroidectomy is surgery to remove all or part of your thyroid gland. Your thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland located at the base of your neck. Thyroid gland produces hormones that regulate every aspect of your metabolism, from your heart rate to how quickly you burn calories.

Thyroidectomy is used to treat thyroid disorders, such as thyroid cancer, noncancerous enlargement of the thyroid (goiter) and overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism).

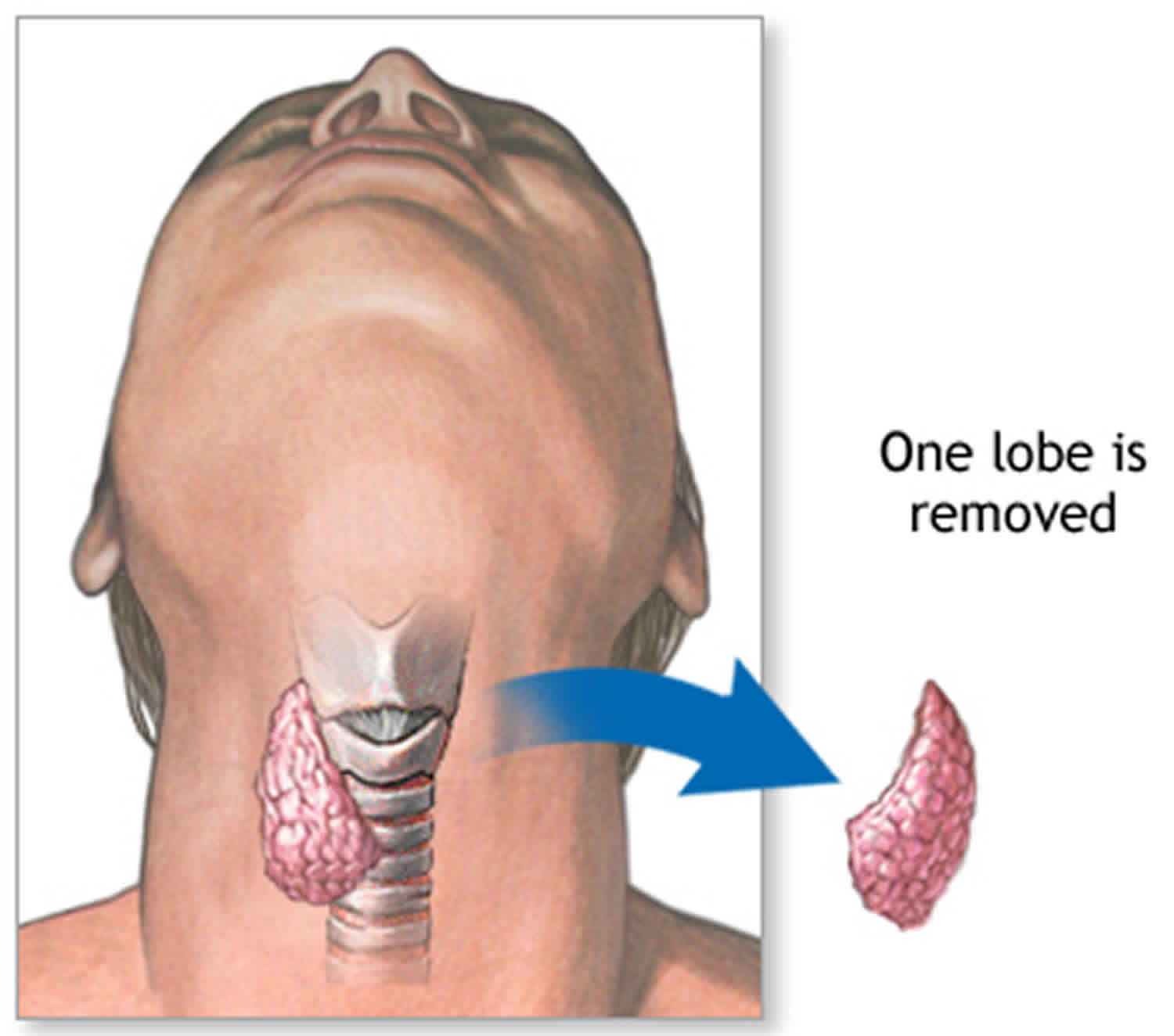

How much of your thyroid gland is removed during thyroidectomy depends on the reason for surgery. If only a portion is removed (partial thyroidectomy), your thyroid may be able to function normally after surgery. If your entire thyroid is removed (total thyroidectomy), you need daily treatment with thyroid hormone to replace your thyroid’s natural function.

The extent of your thyroid surgery should be discussed by you and your thyroid surgeon and can generally be classified as a partial thyroidectomy or a total thyroidectomy. Removal of part of the thyroid can be classified as:

- An open thyroid biopsy – a rarely used operation where a nodule is excised directly;

- A hemi-thyroidectomy or thyroid lobectomy – where one lobe (one half) of the thyroid is removed;

- An isthmusectomy – removal of just the bridge of thyroid tissue between the two lobes; used specifically for small tumors that are located in the isthmus.

- Finally, a total or near-total thyroidectomy is removal of all or most of the thyroid tissue.

The recommendation as to the extent of thyroid surgery will be determined by the reason for the surgery. For instance, a nodule confined to one side of the thyroid may be treated with a hemithyroidectomy. If you are being evaluated for a large bilateral goiter or a large thyroid cancer, then you will probably have a recommendation for a total thyroidectomy. However, the extent of surgery is both a complex medical decision as well as a complex personal decision and should be made in conjunction with your endocrinologist and surgeon.

Your surgeon should explain the planned thyroid operation, such as thyroid lobectomy (partial thyroidectomy or hemi-thyroidectomy) or total thyroidectomy, and the reasons why such a procedure is recommended.

For patients with papillary or follicular thyroid cancer, many, but not all, surgeons recommend total or near total thyroidectomy when they believe that subsequent treatment with radioactive iodine might be necessary. For patients with larger (>1.5 cm) or more invasive cancers and for patients with medullary thyroid cancer, local lymph node dissection may be necessary to remove possibly involved lymph node metastases.

A partial thyroidectomy (hemi-thyroidectomy) may be recommended for overactive solitary nodules or for benign one sided nodules that are causing local symptoms such as compression, hoarseness, shortness of breath or difficulty swallowing. A total or near – total thyroidectomy may be recommended for patients with Graves’ Disease or for patients with large multinodular goiters.

Thyroidectomy surgery usually takes 2-2½ hours, after which time you will slowly wake up in the recovery room. Surgery may be performed through a standard incision in the neck or may be done through a smaller incision with the aid of a video camera (minimally invasive video assisted thyroidectomy). Under special circumstances, thyroid surgery can be performed with the assistance of a robot through a distant incision in either the axilla (armpit) or the back of the neck. There may be a surgical drain in the incision in your neck (which will be removed after the surgery) and your throat may be sore because of the breathing tube placed during the operation. Once you are fully awake, you will be allowed to have something light to eat and drink. Many patients having thyroid operations, especially after hemithyroidectomy, are able to go home the same day after a period of observation in the hospital. Some patients will be admitted to the hospital overnight and discharged the next morning.

Success of a thyroidectomy to remove thyroid cancer depends on the type of cancer and whether it has spread (metastasized) to other parts of the body. You may need follow-up treatment to help prevent the cancer from returning or to treat cancer that has spread.

If a large non-cancerous (benign) nodule causes symptoms, such as pain or problems breathing or swallowing, surgery may help relieve symptoms. All or part of the thyroid gland may be removed. Surgery may also help relieve symptoms if other treatments, such as draining a non-cancerous nodule filled with fluid (cyst), have not worked. Surgery may also be an effective treatment if you have a thyroid nodule that makes too much thyroid hormone.

Figure 1. Thyroid gland and parathyroid gland

Footnotes: Anatomy of the thyroid and parathyroid glands. The thyroid gland lies at the base of the throat near the trachea. It is shaped like a butterfly, with the right lobe and left lobe connected by a thin piece of tissue called the isthmus. The parathyroid glands are four pea-sized organs found in the neck near the thyroid. The thyroid and parathyroid glands make hormones.

Figure 2. Partial thyroidectomy (hemi-thyroidectomy or thyroid lobectomy)

Figure 3. Thyroidectomy scar

Partial thyroidectomy

Subtotal or partial thyroidectomy removes part of the thyroid gland. If only part of your thyroid gland is removed, the remaining portion typically takes over the function of the entire thyroid gland, and you might not need thyroid hormone therapy.

Thyroid lobectomy

Thyroid lobectomy with or without an isthmectomy. If your thyroid nodules are located in one lobe, your surgeon will remove only that lobe (lobectomy). With an isthmectomy, the narrow band of tissue (isthmus) that connects the two lobes also is removed. After the surgery, your nodule will be examined under a microscope to see whether there are any cancer cells. If there are cancer cells, your surgeon may perform a complete thyroidectomy.

Subtotal (near-total) thyroidectomy

Subtotal (near-total) thyroidectomy. Your surgeon will remove one complete lobe, the isthmus, and part of the other lobe. This is used for hyperthyroidism caused by Graves’ disease.

Total thyroidectomy

Total thyroidectomy removes the entire thyroid gland and the lymph nodes surrounding the thyroid gland. Both sections (lobes) of the thyroid gland are usually removed. If you have thyroid cancer, additional treatments with thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) suppression and radioactive iodine work best when as much of the thyroid is removed as possible.

If your entire thyroid gland is removed, your body can’t make thyroid hormone and without replacement you’ll develop signs and symptoms of underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism). As a result, you’ll need to take a pill every day that contains the synthetic thyroid hormone levothyroxine (Levoxyl, Synthroid, Unithroid) for the rest of your life.

This hormone replacement is identical to the hormone normally made by your thyroid gland and performs all of the same functions. Your doctor will determine the amount of thyroid hormone replacement you need based on blood tests.

Will I need to take a thyroid pill after my thyroidectomy?

The answer to this depends on how much of the thyroid gland is removed. If half (hemi) thyroidectomy is performed, there is an 80% chance you will not require a thyroid pill UNLESS you are already on thyroid medication for low thyroid hormone levels (e.g. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) or have evidence that your thyroid function is on the lower side in your thyroid blood tests. If you have your entire gland removed (total thyroidectomy) or if you have had prior thyroid surgery and now are facing removal of the remaining thyroid (completion thyroidectomy) then you have no internal source of thyroid hormone remaining and you will definitely need lifelong thyroid hormone replacement.

Will I be able to lead a normal life after thyroidectomy surgery?

Yes. Once you have recovered from the effects of thyroid surgery, you will usually be able to do anything that you could do prior to surgery. Some patients become hypothyroid following thyroid surgery, requiring treatment with thyroid hormone (see Hypothyroidism brochure). This is especially true if you had your whole thyroid gland removed. Generally, you will be started on thyroid hormone the day after surgery, even if there are plans for treatment with radioactive iodine.

Thyroidectomy indications

Thyroidectomy is usually performed for the following reasons:

- Thyroid cancer. Cancer is the most common reason for thyroidectomy. If you have thyroid cancer, removing most, if not all, of your thyroid will likely be a treatment option.

- Noncancerous enlargement of the thyroid (goiter). Removing all or part of your thyroid gland is an option if you have a large goiter that is uncomfortable or causes difficulty breathing or swallowing or, in some cases, if the goiter is causing hyperthyroidism.

- Indeterminate or suspicious thyroid nodules. Some thyroid nodules can’t be identified as cancerous or noncancerous after testing a sample from a needle biopsy or fine-needle aspiration (FNA). Doctors may recommend that people with these nodules have thyroidectomy if the nodules have an increased risk of being cancerous.

- Overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism) (rarely). Hyperthyroidism or thyrotoxicosis is a condition in which your thyroid gland produces too much of the hormone thyroxine. If you have problems with anti-thyroid drugs and don’t want radioactive iodine therapy, thyroidectomy may be an option for those with those with Graves’ disease and others with hot thyroid nodules (either a toxic nodule or a toxic multinodular goiter). Surgery also may be done if you are pregnant or cannot tolerate antithyroid medicines.

Thyroidectomy surgery

How you prepare for a thyroidectomy surgery

As for other operations, all patients considering thyroid surgery should be evaluated preoperatively with a thorough and detailed medical history and physical exam including cardiopulmonary (heart and lungs) evaluation. An electrocardiogram and a chest x-ray prior to surgery are often recommended for patients who are over 45 years of age or who are symptomatic from heart disease. Blood tests may be performed to determine if a bleeding disorder is present.

Importantly, any patient who has had a change in voice or who has had a previous neck operation (thyroid surgery, parathyroid surgery, spine surgery, carotid artery surgery, etc.) and/or who has had a suspected invasive thyroid cancer should have their vocal cord function evaluated routinely before surgery. This is necessary to determine whether the recurrent laryngeal nerves that control the vocal cord muscles are functioning normally.

Finally, in rare cases, if medullary thyroid cancer is suspected, patients should be evaluated for endocrine tumors that occur as part of familial syndromes including adrenal tumors (pheochromocytomas) and enlarged parathyroid glands that produce excess parathyroid hormone (hyperparathyroidism).

Food and medications

If you have hyperthyroidism, your doctor may prescribe medication — such as an iodine and potassium solution — to regulate your thyroid function and decrease the risk of bleeding.

You may need to avoid eating and drinking for a certain period of time before surgery, as well, to avoid anesthesia complications. Your doctor will provide specific instructions.

Other precautions

Before your scheduled surgery, ask a friend or loved one to help you home after the procedure. Be sure to leave jewelry and valuables at home.

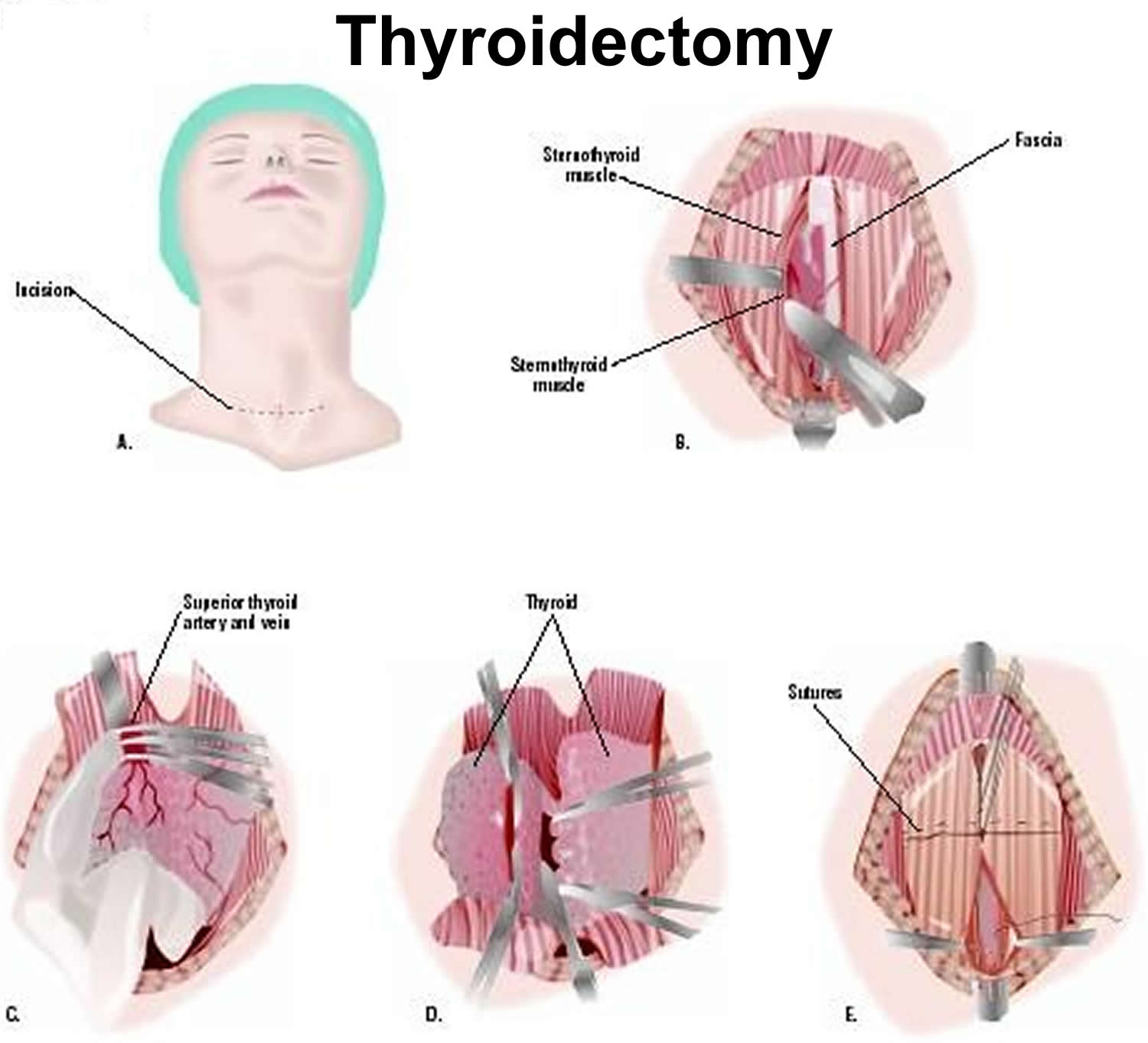

Thyroidectomy procedure

Surgeons typically perform thyroidectomy during general anesthesia, so you won’t be conscious during the procedure. The anesthesiologist or anesthetist gives you an anesthetic medication as a gas — to breathe through a mask — or injects a liquid medication into a vein. A breathing tube will then be placed in your trachea to assist breathing throughout the procedure. In rare cases, thyroidectomy surgery is done with local anesthesia and medicine to relax you. You will be awake, but pain-free.

The surgical team places several monitors on your body to help make sure that your heart rate, blood pressure and blood oxygen remain at safe levels throughout the procedure. These monitors include a blood pressure cuff on your arm and heart-monitor leads attached to your chest.

During the procedure

Once you’re unconscious, the surgeon makes a horizontal cut in the front of your lower neck just above the collar bones (low in the center of your neck). It can often be placed in a skin crease where it will be difficult to see after the incision heals. All or part of the thyroid gland is then removed, depending on the reason for the surgery.

If you’re having thyroidectomy as a result of thyroid cancer, the surgeon may also examine and remove lymph nodes around your thyroid. Thyroidectomy usually takes one to two hours. It may take more or less time, depending on the extent of the surgery needed.

There are several approaches to thyroidectomy, including:

- Conventional thyroidectomy. This approach involves making an incision in the center of your neck to directly access your thyroid gland. The majority of people will likely be candidates for this procedure.

- Transoral thyroidectomy. This approach avoids a neck incision by using an incision inside the mouth.

- Endoscopic thyroidectomy. This approach uses smaller incisions in the neck. Surgical instruments and a small video camera are inserted through the incisions. The camera guides your surgeon through the procedure.

Thyroidectomy recovery

After thyroidectomy surgery, you’re moved to a recovery room where the health care team monitors your recovery from the surgery and anesthesia. Once you’re fully conscious, you’ll be moved to a hospital room.

Some people may need to have a drain placed under the incision in the neck. This drain is usually removed the morning after surgery.

Post thyroidectomy, a few people may experience neck pain and a hoarse or weak voice. This doesn’t necessarily mean there’s permanent damage to the nerve that controls the vocal cords. These symptoms are often temporary and may be due to irritation from the breathing tube (endotracheal tube) that’s inserted into the windpipe (trachea) during surgery, or as a result of nerve irritation caused by the surgery. For most people, these problems get better within 3 to 4 months, but it can take as long as a year. In some cases, this surgery causes permanent problems with chewing, speaking, or swallowing.

You’ll be able to eat and drink as usual after surgery. Depending on the type of surgery you had, you may be able to go home the day of your procedure or your doctor may recommend you stay overnight in the hospital.

Many people leave the hospital a day or two after thyroidectomy surgery. How much time you spend in the hospital and how fast you recover depend on your age and general health, the extent of the surgery, and whether cancer is present.

When you go home, you can usually return to your regular activities. Wait at least 10 days to two weeks before doing anything vigorous, such as heavy lifting or strenuous sports.

Most surgeons prefer that patients limit extreme physical activities following surgery for a few days or weeks. This is primarily to reduce the risk of a postoperative neck hematoma (blood clot) and breaking of stitches in the wound closure. These limitations are brief, usually followed by a quick transition back to unrestricted activity. Normal activity can begin on the first postoperative day. Vigorous sports, such as swimming, and activities that include heavy lifting should be delayed for at least ten days to 2 weeks.

It takes up to a year for the scar from surgery to fade. Your doctor may recommend using sunscreen to help minimize the scar from being noticeable.

The long-term effects of thyroidectomy depend on how much of the thyroid is removed.

Call your local emergency services number anytime you think you may need emergency care. For example, call if:

- You passed out (lost consciousness).

- You have sudden chest pain and shortness of breath, or you cough up blood.

- You have severe trouble breathing.

Call your doctor or seek immediate medical care if:

- You have loose stitches, or your incision comes open.

- Bleeding from your incision soaks through your bandages.

- You have signs of infection, such as:

- Increased pain, swelling, warmth, or redness.

- Red streaks leading from the incision.

- Pus draining from the incision.

- A fever.

- You have a tingling feeling around your mouth.

- You have cramping or tingling in your hands and feet.

Watch closely for changes in your health, and be sure to contact your doctor or nurse call line if:

- You have trouble talking.

- You are sick to your stomach or cannot keep fluids down.

- You do not have a bowel movement after taking a laxative.

How to you care for yourself at home

Incision care

- If your doctor told you how to care for your incision, follow your doctor’s instructions. If you did not get instructions, follow this general advice:

- After the first 24 to 48 hours, wash around the wound with clean water 2 times a day. Don’t use hydrogen peroxide or alcohol, which can slow healing.

- You may have a drain near your incision. Your doctor will tell you how to take care of it.

Activity

- Rest when you feel tired. Getting enough sleep will help you recover. When you lie down, put two or three pillows under your head to keep it raised.

- Try to walk each day. Start by walking a little more than you did the day before. Bit by bit, increase the amount you walk. Walking boosts blood flow and helps prevent pneumonia and constipation.

- Avoid strenuous physical activity and lifting heavy objects for 3 weeks after surgery or until your doctor says it is okay.

- Do not over-extend your neck backwards for 2 weeks after surgery.

- Ask your doctor when you can drive again.

- You may take a shower, unless you still have a drain near your incision. Pat the incision dry. If you have a drain, follow your doctor’s instructions to care for it.

Diet

- If it is painful to swallow, start out with cold drinks, flavoured ice pops, and ice cream. Next, try soft foods like pudding, yogurt, canned or cooked fruit, scrambled eggs, and mashed potatoes. Avoid eating hard or scratchy foods like chips or raw vegetables. Avoid orange or tomato juice and other acidic foods that can sting the throat.

- If you cough right after drinking, try drinking thicker liquids, such as a smoothie.

- You may notice that your bowel movements are not regular right after your surgery. This is common. Try to avoid constipation and straining with bowel movements. You may want to take a fibre supplement every day. If you have not had a bowel movement after a couple of days, ask your doctor about taking a mild laxative.

Medicines

- Your doctor will tell you if and when you can restart your medicines. He or she will also give you instructions about taking any new medicines.

- If you take blood thinners, such as warfarin (Coumadin), clopidogrel (Plavix), or aspirin, be sure to talk to your doctor. He or she will tell you if and when to start taking those medicines again. Make sure that you understand exactly what your doctor wants you to do.

- Take pain medicines exactly as directed.

- If the doctor gave you a prescription medicine for pain, take it as prescribed.

- If you are not taking a prescription pain medicine, ask your doctor if you can take an over-the-counter medicine.

- If you think your pain medicine is making you sick to your stomach:

- Take your medicine after meals (unless your doctor has told you not to).

- Ask your doctor for a different pain medicine.

- Your doctor may prescribe calcium to prevent problems after surgery from low calcium. Not having enough calcium can cause symptoms such as tingling around your mouth or in your hands and feet.

- Your doctor may have prescribed antibiotics. Take them as directed. Do not stop taking them just because you feel better. You need to take the full course of antibiotics.

Follow-up care

Be sure to make and go to all appointments, and call your doctor or nurse call line if you are having problems. It’s also a good idea to know your test results and keep a list of the medicines you take.

Thyroidectomy complications

In experienced hands, thyroidectomy is generally a very safe procedure. But as with any surgery, thyroidectomy carries a risk of complications. Complications are uncommon, but the most serious possible complications of thyroid surgery include:

- Bleeding in the hours right after surgery that could lead to acute respiratory distress.

- Infection.

- Low parathyroid hormone levels (hypoparathyroidism) and hypocalcemia (low blood calcium levels) caused by surgical damage or removal of the parathyroid glands. These glands are located behind your thyroid and regulate blood calcium. Hypoparathyroidism can cause numbness, tingling or cramping due to low blood-calcium levels.

- Airway obstruction caused by bleeding.

- Death: <1%

- Permanent hypothyroidism: 20-30% or greater

- Recurrent hyperthyroidism: <15%

- Permanent hoarse or weak voice due to nerve damage. Vocal cord paralysis: ~1% due injury to a recurrent laryngeal nerve that can cause temporary or permanent hoarseness, and possibly even acute respiratory distress in the very rare event that both nerves are injured;

- Hypoparathyroidism: ~1%

These complications occur more frequently in patients with invasive tumors or extensive lymph node involvement, in patients undergoing a second thyroid surgery, and in patients with large goiters that go below the collarbone into the top of the chest (substernal goiter). Overall the risk of any serious complication should be less than 2%. However, the risk of complications discussed with the patient should be the particular surgeon’s risks rather than that quoted in the literature. Prior to surgery, patients should understand the reasons for the operation, the alternative methods of treatment, and the potential risks and benefits of the operation (informed consent).

Thyroid Storm

Thyroid storm reflects an exacerbation of a thyrotoxic state; it is seen most often in Graves’ disease, but it occurs less commonly in patients with toxic adenoma or toxic multinodular goiter.

Wound Hemorrhage

Wound hemorrhage with hematoma is an uncommon complication reported in 0.3% to 1.0% of patients in most large series. However, it is a well-recognized and potentially lethal complication 1. A small hematoma deep to the strap muscles can compress the trachea and cause respiratory distress. A small suction drain placed in the wound is not usually adequate for decompression, especially if bleeding occurs from an arterial vessel. Swelling of the neck and bulging of the wound can be quickly followed by respiratory impairment.

Wound hemorrhage with hematoma is an emergency situation, especially if any respiratory compromise is present. Treatment consists of immediately opening the wound and evacuating the clot, even at the bedside. Pressure should be applied with a sterile sponge and the patient returned to the operating room. Later, the bleeding vessel can be ligated in a careful and more leisurely manner under optimal sterile conditions with good lighting in the operating room. The urgency of treating this condition as soon as it is recognized cannot be overemphasized, especially if respiratory compromise is present.

Injury to the Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve

Injuries to the recurrent laryngeal nerve occur in 1% to 2% of thyroid operations when performed by experienced neck surgeons, and at a higher prevalence when thyroidectomy is done by a less experienced surgeon 2. They occur more commonly when thyroidectomy is performed for malignant disease, especially if a total thyroidectomy is done. Sometimes the nerve is purposely sacrificed if it runs into an aggressive thyroid cancer. Nerve injuries can be unilateral or bilateral and temporary or permanent, and they can be deliberate or accidental. Loss of function can be caused by transection, ligation, clamping, traction, or handling of the nerve. Tumor invasion can also involve the nerve. Occasionally, vocal cord impairment occurs as a result of pressure from the balloon of an endotracheal tube on the recurrent nerve as it enters the larynx. In unilateral recurrent nerve injuries, the voice becomes husky because the vocal cords do not approximate one another. Shortness of breath and aspiration of liquids sometimes occur as well. Most nerve injuries are temporary and vocal cord function returns within several months; it certainly returns within 9 to 12 months if it is to return at all. If no function returns by that time, the voice can be improved by operative means. The choice is insertion of a piece of Silastic to move the paralyzed cord to the midline; this procedure is called a laryngoplasty. Early in the course of management of a patient with hoarseness or aspiration, the affected vocal cord can be injected with various substances to move it to the midline and to alleviate or improve these symptoms.

Bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve damage is much more serious, because both vocal cords may assume a medial or paramedian position and cause airway obstruction and difficulty with respiratory toilet. Most often, tracheostomy is required. Permanent injuries to the recurrent laryngeal nerve are best avoided by identifying and carefully tracing the path of the recurrent nerve. Accidental transection occurs most often at the level of the upper two tracheal rings, where the nerve closely approximates the thyroid lobe in the area of Berry’s ligament. If recognized, many believe that the transected nerve should be reapproximated by microsurgical techniques, although this is controversial. A number of procedures to later reinnervate the laryngeal muscles have been performed with improvement of the voice in unilateral nerve injuries, but with only limited success when a bilateral nerve injury has occurred 3.

Injury to the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve may occur when the upper pole vessels are divided if the nerve is not visualized 4. This injury results in impairment of function of the ipsilateral cricothyroid muscle, a fine tuner of the vocal cord. This injury causes an inability to forcefully project one’s voice or to sing high notes because of loss of function of the cricothyroid muscle. Often, this disability improves during the first few months after surgery.

Many surgeons have sought to try to further diminish the low incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury by use of nerve monitoring devices during surgery. Although several devices have been utilized, all have in common some means of detecting vocal cord movement when the recurrent laryngeal nerve or the ipsilateral vagus nerve is stimulated. Many small series have been reported in the literature assessing the potential benefits of monitoring to decrease the incidence of nerve injury 5. Given the low incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, it is not surprising that no study has shown a statistically significant decrease in recurrent laryngeal nerve injury when using a nerve monitor. The largest series in the literature by Dralle 6 reported on a multi-institutional German study of 29,998 nerves at risk in thyroidectomy. Even with a study this large, no statistically significant decrease in rates of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury could be shown with nerve monitoring. Despite this, the use of nerve monitoring has become more popular.

Among the problems of nerve monitoring technology are that the devices can malfunction, often because of endotracheal tube misplacement, so that the surgeon cannot depend on the device to always identify the nerve. Proponents of nerve monitoring suggest that the technology is helpful even if a statistically significant decrease in the rate of recurrent laryngeal nerve cannot be shown. Goretzki and his group 7, for example, have published data that when operating upon bilateral thyroid disease, if nerve monitoring suggests a nerve injury on the first side, they have modified or restricted the resection of the contralateral thyroid lobe. In this way, they have decreased or eliminated the incidence of bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injuries. This is very important.

Many authors have suggested that recurrent laryngeal nerve monitors may be most helpful in difficult reoperative cases when significant scar tissue is encountered, and have limited their use to such cases. This has not generally been shown to be the case. Most authors have advocated routine use 8. Nerve monitoring technology in thyroid surgery should never take the place of meticulous dissection. Surgeons may choose to use the technology, but the data do not support the suggestion that nerve monitors allow thyroid surgery to be performed in a safer fashion than that by a good surgeon utilizing careful technique. An excellent international guide to the use of electrophysiologic recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring during thyroid and parathyroid surgery has been published 9. Furthermore, a review of the medical, legal, and ethical aspects of recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring has been written by Angelos 10.

A recent advance is continuous intraoperative recurrent laryngeal monitoring, done by continuously stimulating the ipsilateral vagus nerve. It has been shown that a decrease in signal amplitude and an increase in signal latency often occur before some recurrent laryngeal nerves are permanently damaged. In a recent experimental study, it was shown that modification of the surgical maneuver by the operator (such as release of traction) led to recovery of the EMG changes and aversion of the impending recurrent nerve injury 11. This technique shows great promise for helping the surgeon intraoperatively, for it signals that the nerve is in danger and that the surgeon should stop doing whatever is causing the problem. A note of caution is appropriate, however. Terris and associates 12 recently described two serious adverse events in nine patients who underwent continuous vagal nerve monitoring—hemodynamic instability and reversible vagal neuropraxia—both attributable to the monitoring apparatus. They feel that this technique may cause harm and they have stopped its routine use. Clearly, further clarification and study must be done, but surgeons should use caution until it’s safety has been proved.

Hypoparathyroidism

Postoperative hypoparathyroidism can be temporary or permanent. The incidence of permanent hypoparathyroidism has been reported to be as high as 20% when total thyroidectomy and radical neck dissection are performed, and as low as 0.9% for subtotal thyroidectomy. Other excellent neck surgeons have reported a lower incidence of permanent hypoparathyroidism, even about one percent following total thyroidectomy 13. Postoperative hypoparathyroidism is rarely the result of inadvertent removal of all of the parathyroid glands but is more commonly caused by disruption of their delicate blood supply. Devascularization can be minimized during thyroid lobectomy by dissecting close to the thyroid capsule, by carefully ligating the branches of the inferior thyroid artery on the thyroid capsule distal to their supply of the parathyroid glands (rather than ligating the inferior thyroid artery as a single trunk), and by treating the parathyroids with great care. If a parathyroid gland is recognized to be ischemic or nonviable during surgery, it can be autotransplanted often after identification by frozen section. The gland is minced into 1 to 2 mm cubes and placed into a pocket(s) in the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Postoperative hypoparathyroidism results in hypocalcemia and hyperphosphatemia; it is manifested by circumoral numbness, tingling of the fingers and toes, and intense anxiety occurring soon after surgery. Chvostek’s sign appears early, and carpopedal spasm can occur. Symptoms develop in most patients when the serum calcium level is less than 7.5 to 8 mg/dL. Parathyroid hormone is low or absent in most cases of permanent hyopoparathyroidism.

Patients who have had a thyroid lobectomy rarely develop significant hypocalcemia postoperatively since two contralateral parathyroid glands are left intact. Many of these patients may be discharged on the day of operation if they are otherwise satisfactory. However, patients who have had a total or near total thyroidectomy for cancer or for Graves’ disease are at greater risk of a low calcium and are generally observed in the hospital postoperatively. We have found the one hour postoperative parathyroid hormone (PTH) level to be equivalent to the parathyroid hormone level drawn the following morning. A value of 15 pg/ml or greater at one hour is very reassuring and is rarely associated with symptomatic postoperative hypocalcemia or with permanent hypoparathyroidism. A central lymph node dissection makes transient hypocalcemia more likely.

As well as one hour parathyroid hormone (PTH), measure the serum calcium and parathyroid hormone levels approximately 12 hours after operation and thereafter. Most patients are able to leave the hospital on the morning after surgery if they are asymptomatic and their serum calcium level is 7.8 mg/dL or above. Oral calcium pills are used liberally. Patients with severe symptomatic hypocalcemia are treated in the hospital with 1 g (10 mL) of 10% calcium gluconate infused intravenously over several minutes. Then, if necessary, 5 g of this calcium solution is placed in each 500 mL intravenous bottle to run continuously, starting with approximately 30 mL/hour. Oral calcium, usually as calcium carbonate (1250 mg to 2500 mg four times per day), should be started. Each 1250 mg pill of calcium carbonate contains 500 mg of calcium. With this treatment regimen most patients become asymptomatic. The intravenous therapy is tapered and stopped as soon as possible, and the patient is sent home and told to take oral calcium pills. This condition is referred to as transient or temporary hypocalcemia or transient hypoparathyroidism. Serum phosphorus determinations are helpful to rule out bone hunger in which both calcium and phosphorus levels are low, while parathyroid hormone (PTH) may be normal.

Management of persistent severe hypocalcemia requires the addition of a vitamin D preparation to facilitate the absorption of oral calcium. Some experts prefer the use of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (Calcitriol) because it is the active metabolite of vitamin D and has a more rapid action than regular vitamin D. Calcitriol 0.5 mcg with oral calcium carbonate therapy is given four times daily for the first several days, then this priming dose of vitamin D is reduced. The usual maintenance dose for most patients with permanent hypoparathyroidism is Calcitriol 0.25 to 0.5 mcg once daily, along with calcium carbonate, 500 mg Ca 2+ once or twice daily, although some patients require larger doses. When high doses of vitamins are used, serum calcium levels must be monitored carefully after discharge, and the dosage of the medications is adjusted promptly to prevent hypercalcemia as well as hypocalcemia. Finally, the serum parathyroid hormone level should be analyzed periodically to determine whether permanent hypoparathyroidism is truly present, because the authors and others have seen cases of postoperative tetany, perhaps caused by “bone hunger,” that later resolved completely. In such cases, circulating parathyroid hormone is normal and all therapy can be stopped. Remember that in bone hunger, both the serum calcium and phosphorus values are low, whereas in hypoparathyroidism, the serum calcium value is low but the phosphorus level is elevated. Permanent hypoparathyroidism is usually not diagnosed until at least six months have passed and parathyroid hormone remains low or absent.

McHenry 14 has shown that the incidence of complications following thyroidectomy varies greatly. In general, those surgeons with excellent training and a large experience with this operation have fewer complications, particularly following cancer procedures and reoperative surgery.

References- Schwartz AE, Clark O, Ituarte P, LoGerfo P: Therapeutic controversy. Thyroid surgery: The choice. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:1097–1105, 1998

- Kaplan E, Angelos P, Applewhite M, et al. Chapter 21 SURGERY OF THE THYROID. [Updated 2015 Sep 25]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK285564

- Miyauchi A, Matsusaka K, Kihara M, et al: The role of ansa to recurrent laryngeal nerve anastomosis in operations for thyroid cancer. Eur J Surg 164:927–933, 1998.

- Lennquist S, Cahlin C, Smeds S: The superior laryngeal nerve in thyroid surgery. Surgery 102:999, 1987

- Donnellan KA, Pitman KT, Cannon CR, Replogle WH, Simmons JD: Intraoperative laryngeal nerve monitoring during thyroidectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head & Neck Surg 135(12):1196-1198, 2009.

- Dralle H, Sekulla C, Lorenz K, et al: Intraoperative monitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerve in thyroid surgery. World J Surg 32:1358-1366, 2008

- Goretzki PE, Schwarz K, Brinkmann J, Wirowski D, Lammers BJ: The impact of intraoperative neuromonitoring (IONM) on surgical strategy in bilateral thyroid diseases: Is it worth the effort? World J Surg 34:1274-1284, 2010

- McHenry CR: Patient volumes and complications in thyroid surgery. Brit J Surg 89(7):821-823, 2002.

- Randolph GW, Dralle H, with the International Intraoperative Monitoring Study Group, Abdullah H, et al: Electrophysiologic recurrent laryngeal monitoring during thyroid and parathyroid surgery: International standards guideline statement. Laryngoscope 121:S1-S16, 2011.

- Angelos P: Recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring: State of the art, ethical and legal issues. Surg Clin N Amer 89(5):1157-1169, 2009.

- Wu CW, Dionigi G, Sun H: Intraoperative neuromonitoring for the early detection and prevention of RLN traction injury in thyroid surgery: A porcine model. Surgery 155(2):329-339, 2014

- Terris DJ, Chaung K, Duke WS: Continuous vagal nerve monitoring is dangerous and should not routinely be done during thyroid surgery. World J Surg 39(10):2471-2476, 2015

- Pattou F, Combemale F, Fabre S, et al: Hypocalcemia following thyroid surgery: Incidence and prediction of outcome. World J Surg 22:718–724, 1998.

- McHenry CR: Patient volumes and complications in thyroid surgery. Brit J Surg 89(7):821-823, 2002