Traumatic neuroma

Traumatic neuroma also called post traumatic neuroma or amputation neuromas, is a disorganized proliferation of nerve tissue that commonly occurs after a cut or damage including previous surgery to a peripheral nerve bundle 1. A traumatic neuroma is a tangle of neural fibers and connective tissue that develops following nerve injury. It usually presents as a firm, oval, whitish, slowly growing, palpable and painful nodule, not larger than 2 cm. It may be associated with paresthesia over the injured area 2. Painful hypersensitivity to normal light tactile stimuli (dysesthesia) or a neuralgic pain with the presence of a typical trigger point in the area of a neuroma may be a prominent feature. Traumatic neuropathic pain can cause the patient to feel burning, stabbing, raw, gnawing or sickening sensations 2. Traumatic neuromas can occur after amputation of a limb or autoamputation of a digit in utero. The clinical features of a traumatic neuroma include the formation of a solitary nodule less than 2 cm in diameter, neuralgic pain, tenderness, paresthesias and increased pain or tenderness on palpation over the lesion 3. Usually nerves can repair themselves by proximal to distal proliferation of Schwann cells; when this reparation is interrupted or cannot occur in an orderly manner, the proximal aspect of the nerve creates a disorganized proliferation of nerves, that is called a neuroma. Most authors consider the occurrence of traumatic neuroma to be related to excess hyperplasia and irregular hyperplasia after nerve injury, so they are often regarded as benign tumors 4.

Traumatic neuroma may occur in any part of your body, including your head, face, neck, limbs, gallbladder, thigh, mammary gland, penis, and other body parts 5. In the mouth, a traumatic neuroma is a rare disorder that occurs most commonly at the mental foramen, lower lip, tongue and intra-osseous areas 6. Jones and Franklin 7 reported that the frequency of traumatic neuromas was 0.34 % in the oral region. The most common sites for a traumatic neuroma in the head and neck are the inferior alveolar nerve, lingual nerve, and great auricular nerve 8. Traumatic neuroma is extremely rare in the palate.

The borders of diffuse traumatic neuromas are often unclear, and the extent of the actual tumor may be such that a complete excision would result in severe neurologic damage, such as an area of hypoesthesia or complete nerve palsy. In these cases, simple excision of the tumor using an electrical scalpel is an effective method of treatment, and reduces the likelihood that the residual traumatic neuroma tissue would cause repeat symptoms or a full recurrence of the tumor.

The treatment of traumatic neuroma is still considered controversial. Conservative and operative therapy both have its advantage and disadvantage. The recommended treatment of a traumatic neuroma is simple excision rather than nerve resection or alcohol blocks 9. Tay et al. 10 reported that monopolar diathermy reduces the rate of neuroma formation, and electrical coagulation of the proximal nerve stump can prevent the development of neuromas. Simple excision is therefore highly recommended in the treatment of traumatic neuromas 1.

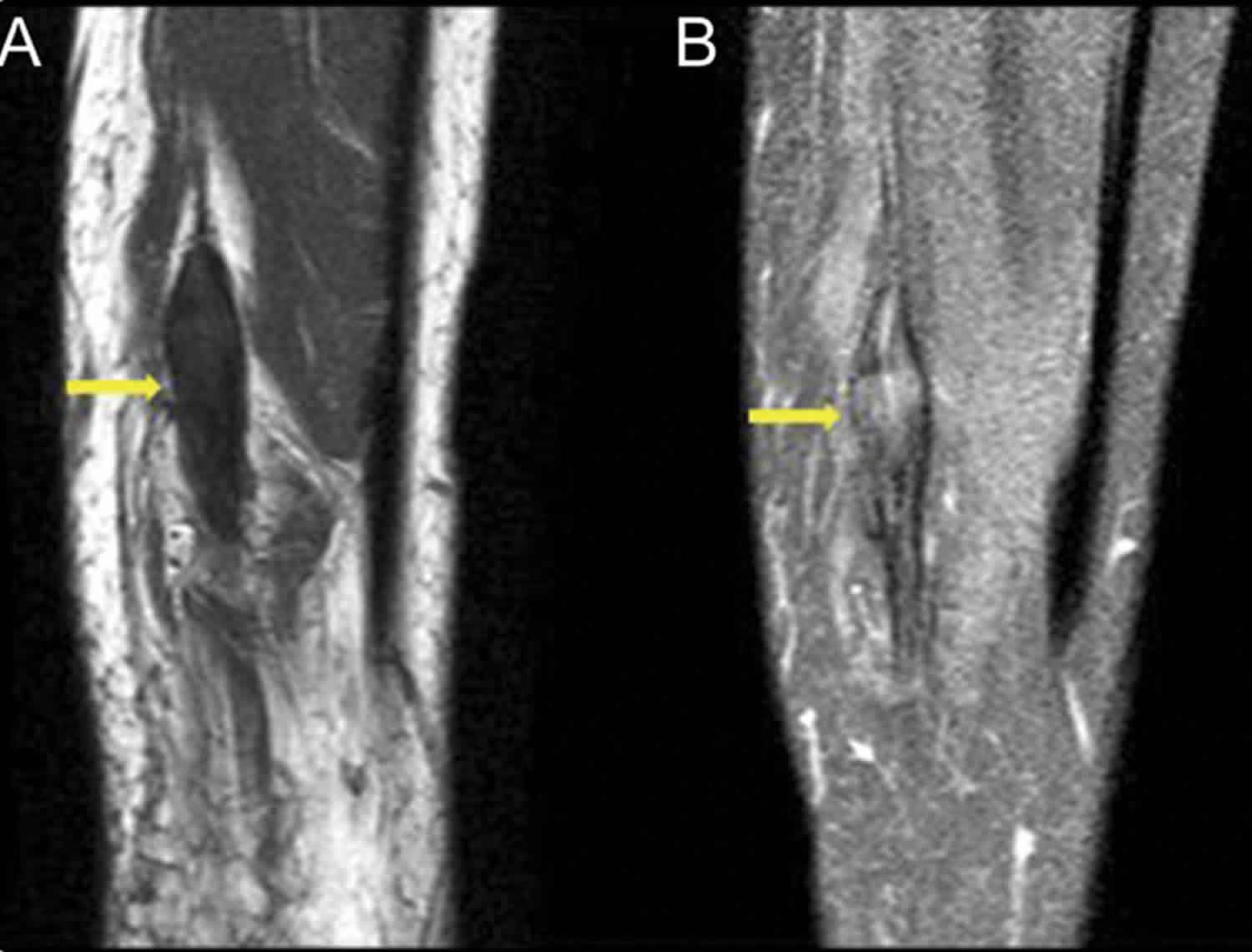

Figure 1. Traumatic neuroma in mouth

Footnote: (a) Photograph showing an obvious swelling of the left palatine mucosa (arrows). (b) A T2-weighted magnetic resonance image showing the lesion as an area of high-signal intensity (arrow).

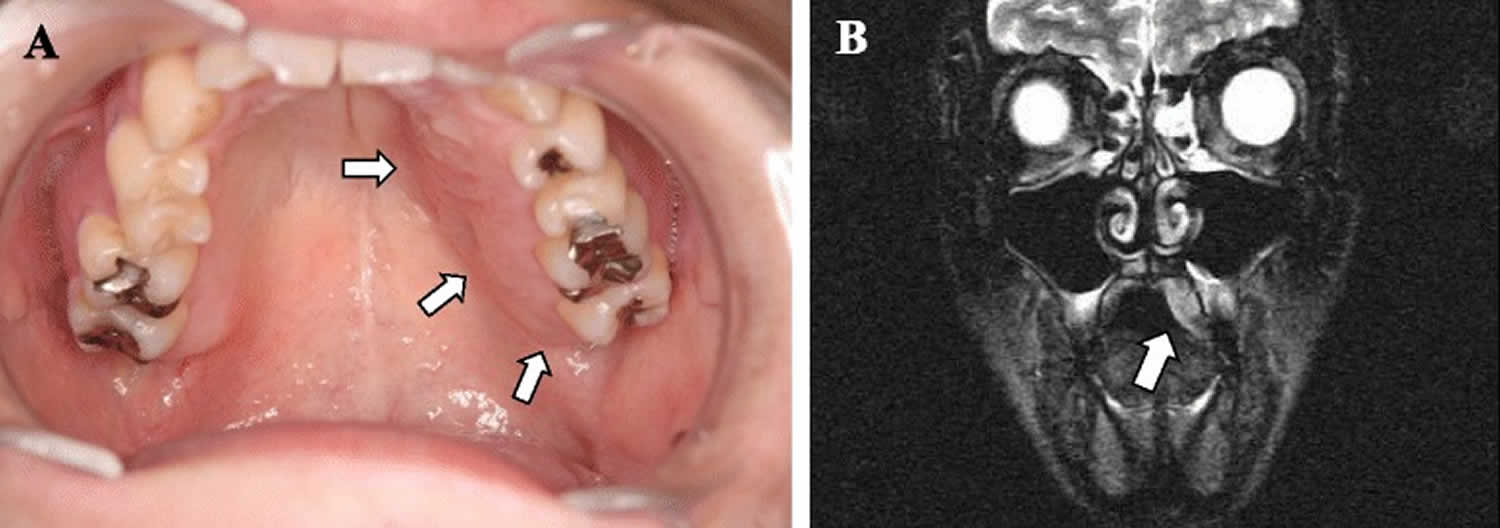

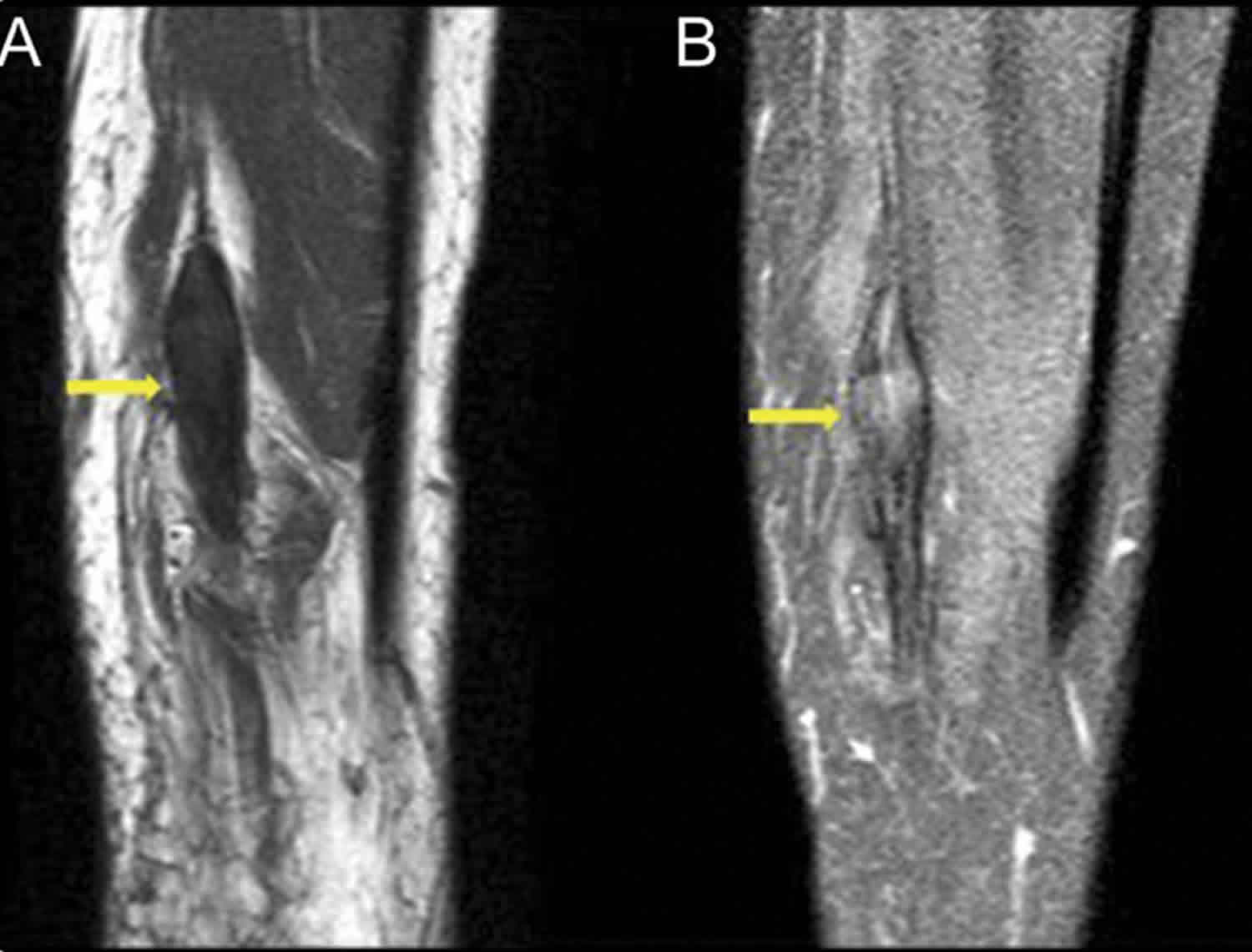

[Source 11 ]Figure 2. Traumatic neuroma knee (MRI right leg)

Footnote: A 40-year-old man with a history of penetrating injury to the right lower leg complained of shooting pain along the distribution of the tibial nerve and the small nodule beneath the cutaneous scar. MRI demonstrated nonenhancing fusiform thickening of the tibial nerve, which was isointense to muscle with perineural scarring. The features were characteristic of posttraumatic neuroma-in-continuity of the right tibial nerve. (A) Sagittal T1-weighted precontrast without fat suppression and (B) T1-weighted postcontrast fat-suppressed MRI show fusiform thickening of the tibial nerve with nerve continuity on either side without significant enhancement of the lesion.

[Source 12 ]Traumatic neuroma causes

Traumatic neuromas can develop after blunt or sharp trauma or traction injury. An essential step in neuroma formation is widely accepted to be the injury of the perineurium as, without an intact perineurium, the axon fibers cannot go through 13. As soon as perineurium is damaged, the axons will escape. Another critical step is thought to be neuroinflammation 14. As the axons get to the extraperineurial space where there is already tissue damage, there will be inflammation. The compounds released during inflammation can aid neuroma formation.

The injured nerve endings start to regenerate in an unregulated fashion disrupting the mostly linear organization of fibers resulting in an unorganized growth. This growth will create and transmit signals which the central nervous system can interpret as pain.

A traumatic neuroma is formed from one of two main processes:

- Spindle neuroma: which commonly occur from a reactive fibroinflammatory disorganized regeneration around a nerve after an injury, such as traction injury or chronic repetitive stress (e.g. Morton neuroma) 15

- Terminal neuroma such as “stump neuroma”: can occur after transection of the proximal nerve terminal after injury or operation (e.g. limb amputation, ilioinguinal pain post herniorrhaphy). It is common to see neuroma formation following elective hand surgery, especially the superficial radial nerve is susceptible, or after knee arthroplasty, the saphenous nerve is vulnerable 16. After nerve division, distal axons begin apoptosis. To reconstruct nerve continuity, Schwann cells of the distal nerve will generate a channel for ingrowth of adjacent axons 17. However, in cases of too long distance between two segments of the injured nerve, proximal axons will grow toward multiple directions around so as to find a way for growth; thus, the appearance generally overgrows in bulbous-end-like shape 17 and besides, as nerve tissues grow more slowly than surrounding soft tissues, they will be mixed with other kinds of cells, such as fibroblast and mastocyte 18.

- There is also a report indicating that facial nerve hemangioma also can lead to traumatic neuroma under the condition of no trauma or operation history and no chronic stimulation and compression 19.

- Causal factors for traumatic neuroma in mouth include tooth extraction, orthognathic surgery, ill-fitting dentures and intra-oral incisions 3.

Mortons neuroma (localized interdigital neuroma) is a traumatic neuroma of the third metatarsal interspace.

Neuromas can develop after amputation called stump neuroma. The symptoms they produce should not be confused with phantom limb pain.

The pain may be generated for the following reasons or mechanisms:

- stretched by surrounding scar tissues 20;

- compression on sensitive teleneuron by surrounding soft tissues 21;

- nerve tissue ischemia 22;

- ectopic foci of ion channels 23;

- P substance, calcitonin gene related peptide and 5-hydroxytryptamine are released by mastocyte 18; and

- peripheral regulation of kinds of ion channels or receptors (sodium channels, TRPA1, alpha1C receptors, and nerve growth factor) 24.

This kind of pain is difficult to control because it is often accompanied by central sensitization and social-psychological factors 25 and the change of voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) may be the important element of central sensitization26.

Traumatic neuroma differential diagnosis

Neuromas can be part of a syndrome such as neurofibromatosis or multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B (MEN2B). Neurofibroma (or neurofibromatosis) is a genetic condition in which multiple neuromas form in various places of the central and peripheral nervous system. They can present as skin lesions, can cause hearing and balance issues or pain. There is no known cure; surgery has a role in symptom control. Multiple endocrine neoplasia 2B (MEN2B) is a genetic syndrome consisting of medullary thyroid carcinoma, pheochromocytoma, and mucosal neuromas.

The histologic differential diagnosis for oral traumatic neuromas includes mucosal neuromas (multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B), neurofibromas, palisading neuromas, and neurovascular hamartomas. On histological examination, mucosal neuromas resemble traumatic neuromas because of the presence of many nerve bundles 27. However, the absence of inflammatory cells in a normal or loose fibrous connective tissue background can lead to the diagnosis of a mucosal neuroma. Neurofibromas and traumatic neuromas both have fibrous connective tissue and non-encapsulated lesions, but neurofibromas have mast cells and nuclei with a wavy or serpiginous prolife, and do not contain the abundant, haphazardly arranged axons that are unique to traumatic neuromas 28. Although palisading neuromas and traumatic neuromas both form nerve bundles 29, the absence of inflammatory cells and fibrous connective tissue and the existence of spindle cells showing palisading arrangement and generally circumscribed margin is more indicative of a palisading neuroma. Neurovascular hamartomas are rarely described in the oral cavity. The histopathologic features of neurovascular hamartomas include poorly circumscribed masses of closely packed nerve bundles and blood vessels in a loose matrix, containing minimal to no inflammation 30. Given all the histologic similarities between these masses, identifying a traumatic neuroma is especially difficult. Allon et al. 30 noted that neurovascular hamartomas are unique histologically because their neural and vascular components are separate, with a dominant neural component. Immunohistochemical staining for factor VIII suggested that the neural and vascular components were separate. In addition, palpable bulging and pain on palpation are signs of a traumatic neuroma. Neurogenic tumors of the head and neck generally do not produce neurologic signs or symptoms 3.

Table 1. Clinical and histopathological differential diagnosis of traumatic neuroma versus other neurogenic tumors

| Clinical features | Histopathological features | |

| Traumatic neuroma | Symptomatic (anesthesia, dysesthesia, and pain), solitary | Many nerve bundles, fibrous connective tissue background containing inflammatory cells |

| Mucosal neuroma | Asymptomatic, typically multiple, associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B | Many nerve bundles, normal or loose fibrous connective tissue background without inflammatory cells |

| Neurofibroma | Asymptomatic, solitary, or multiple | Nuclei with wavy or serpiginous prolife, fibrous connective tissue background containing mast cells |

| Palisading neuroma | Asymptomatic, solitary | Circumscribe, spindle cells showing palisading arrangement |

| Neurovascular hamartoma | Asymptomatic, solitary | Many nerve bundles containing vessels, fibrous connective tissue background without inflammatory cells |

Traumatic neuroma prevention

Traumatic neuroma prevention is essential as it can result in traumatic neuropathic pain, functional impairment and psychological distress, severely decreasing the quality of life 31. Following injuries or during elective operations after transection of a nerve is transected, the surgeon should reconnect the two nerve endings where possible. Following injuries where the nerve damage is suspected, patients must seek medical attention in centers where usually plastic surgeons can diagnose, explore, and treat nerve damage. Many different surgical strategies exist to prevent neuroma formation after trauma, none of which are superior to each other. Neurorraphy significantly reduces neuroma formation to 1% from 7.8% untreated or amputated 32. Generally accepted principal surgical aims are: repair should not be under tension, in a theater environment with loupe or microscope magnification, align nerve so that same axon can reconnect. Careful and minimal debridement is also accepted. If there is a gap, it is common to sacrifice a less crucial sensory nerve to provide a nerve graft for the repair, which can be multi-stranded. If the two ends cannot be rejoined (amputation), it is common to bury the nerve or suture it onto muscle to help prevent neuroma formation; this is called targeted nerve implantation (TNI) 33.

The CoNNECT randomized trial still in progress is looking at end to end, end to end plus conduit, and no direct suture only conduit secured repairs to determine if tubes are beneficial and if sutureless solutions merit consideration.

A study is looking at a local tacrolimus (FK506) embedded polylactide-co-caprolactone films that actively decreased neuroma formation when continuously released to repair site 34.

A group of Chinese scientists is looking into autologous vein grafts to be used instead of nerve grafts to bridge short gaps after nerve injury 35.

There is also work being done to use stem cells to help nerves regenerate after an injury. Although the main aim is to improve function rather than to reduce neuroma formation 36.

Traumatic neuroma symptoms

The main manifestation of traumatic neuroma is pain, especially intense neuralgia 37. Neuroma pain can be burning, sharp, tingling sensation, or numbness. The pain is often characterized by chixuxi low-intensity dull pain or intense paroxysmal burning pain and also can be induced by various outside simulations, such as temperature and touch. Tinel’s sign is usually positive 38.

There is also another pain that may be related to traumatic neuroma, called phantom pain, which results from sensing of the existence of amputated part 39. Ectopic discharge from a stump neuroma has been thought to be an important peripheral mechanism of phantom pain 39. Traumatic neuroma may also be characterized by paresthesia, such as hyperesthesia or feeling of numbness. One study reports on a case traumatic neuroma may have no manifestation during its development 17. Traumatic neuroma symptoms may develop 1-12 months after nerve injury.

There should also be a history of injury (including iatrogenic injury, i.e. surgery) to the area.

Traumatic neuroma diagnosis

The diagnosis of traumatic neuroma is mainly dependent on history and examination. The history of trauma or surgery is very important in the diagnosis of a traumatic neuroma. Special care should be taken to establish where and how was the injury treated, was there any attempt at repairing the nerve. If there is no history of trauma, the differential should shift towards genetic causes of the neuroma and true neoplasms.

On examination, a well defined hard lump is usually palpable, which can be adherent to nearby structures. On pressure, patients can experience a sensation similar to electric shock.

In cases where there is uncertainty, X-rays can be taken to rule out bone injury as a cause of pain and to rule out bone malignancy. Ultrasound, computed tomogram (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will show well-defined soft tissue mass but are rarely necessary investigations.

Ultrasonography is one of most valuable methods in the diagnosis of traumatic neuroma. The position and size of lesion and the relation between lesion and surrounding tissues and nerves can be detected directly via ultrasonography examination. Ultrasonography examination is inexpensive, noninvasive, and non-harmful. Futhermore, local nerve blocking can be conducted under the guidance of ultrasonography for the enhancement of the diagnosis, and pathological examination of living tissue can be implemented for the definite diagnoses 40. Ultrasound image of traumatic neuroma is generally oval, low-echo enclosed mass, clear and irregular probable boundary, diameter being greater than that of nerve trunk, and continuity with nerve 17.

MRI is only used in differential diagnosis with other soft tissue diseases 41 and its cost is high; patients have discomfort and real-time imaging cannot be used for display; thus, MRI has a limited value in diagnosis of traumatic neuroma.

There are no laboratory tests that would aid diagnosis. After surgical excision, it is common practice to send lesions for histopathology examination to rule out malignancy.

At histopathology, traumatic neuromas generally show in the following appearance: nonencapsulated tangled mass formed by Schwann cell, endoneurial cell, perineurial cell, and surrounding fibroblast 15.

Traumatic neuroma treatment

There is no consensus on how to best treat an already formed neuroma 42. The recommended treatment of a traumatic neuroma is simple excision rather than nerve resection or alcohol blocks 9. Tay et al. 10 reported that monopolar diathermy reduces the rate of neuroma formation, and electrical coagulation of the proximal nerve stump can prevent the development of neuromas. Simple excision is therefore highly recommended in the treatment of traumatic neuromas 1.

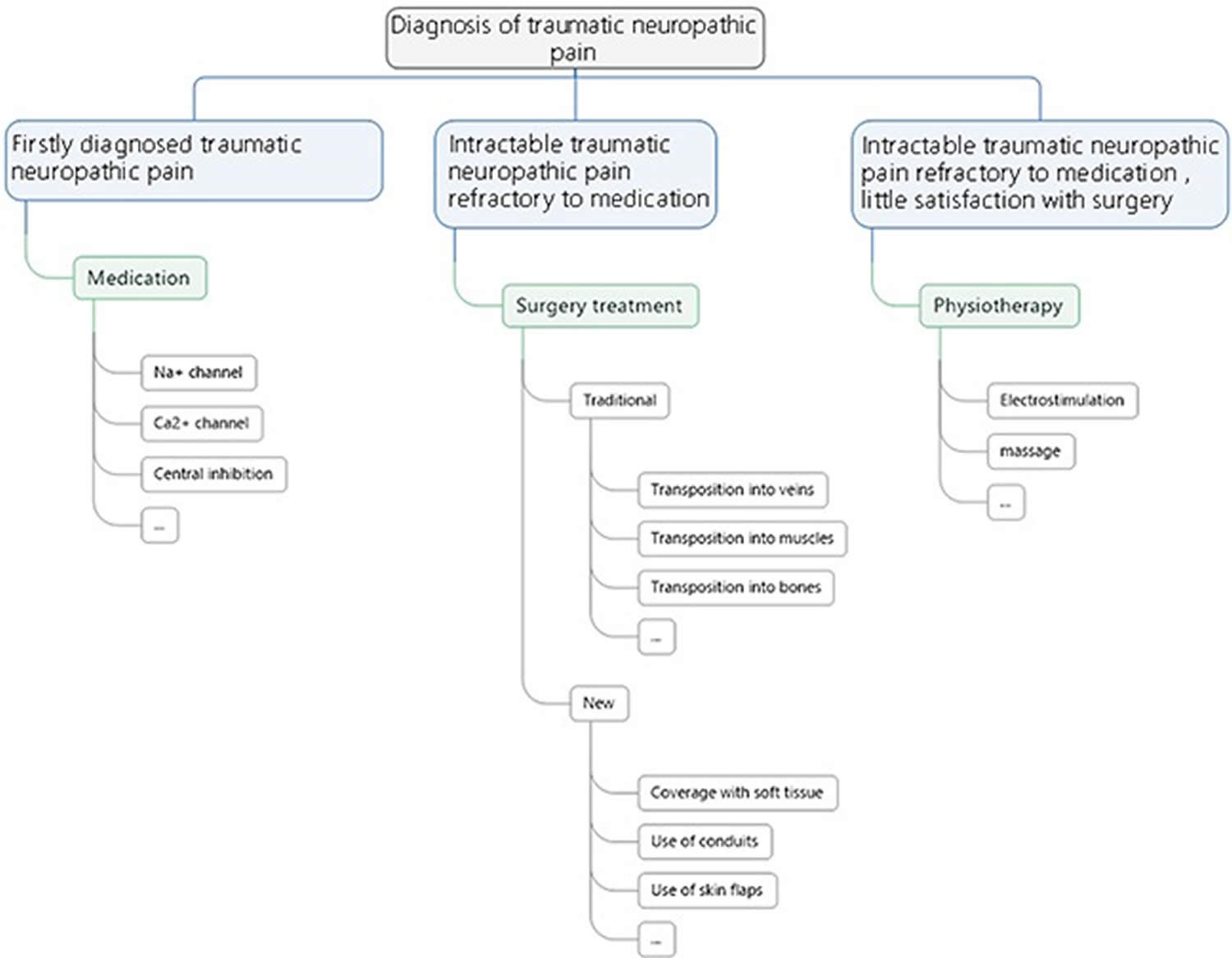

Figure 3. A flowchart of treatment principles for neuropathic pain

[Source 43 ]Conservative therapy

- Medications: Opioid analgesics, antidepressant drugs, antispasmodic drugs, α receptor blockers, and lidocaine are all used in the treatment of traumatic neuroma, but only have short-term therapeutic effect, and show significant side effects and declined therapeutic effect in long-term use 44. Gabapentin and pregabalin are considered the effective medicine to inhibit central sensitization through affecting the calcium channels and reduce the excessive neurotransmitter release 45.

- Repeated injection of lidocaine with steroid: It shows the symptom is improved in painful neuroma but has significant side effects with long-term injection 46.

- B ultrasound-guided percutaneous ethanol injection: can relieve painful neuroma significantly with continuous injection, and has high remission rate 47.

- Transcutaneous magnetic stimulation (TMS): a rapid discharge of electric current is converted into dynamic magnetic flux for modulating neuronal functions 48. This analgesic effect seemed to be sustainable with repeated treatment delivered at a 6- to 8-week duration 48.

- Injection of a tumor necrosis factor etanercept to peripheral nerves can relieve the pain significantly 49.

- Cryotherapy and radiofrequency ablation are both used in clinical treatment, but the therapeutic effect is unsatisfactory. Six months after radiofrequency ablation, there was significant decline in pain relief 50.

Other treatments for traumatic neuropathic pain are mainly physiotherapy. Therapeutic massage is advised by Faith 51 and which is preferred for the treatment of Morton’s neuroma. Electrical stimulation is another common conservative treatment choice. In Stevanato’s et al. study 52, they use an implanted peripheral nerve stimulator applied directly to the nerve branch involved into the axillary cavity. A quadripolar electrode lead was placed directly on the sensory peripheral branch of the main nerve involved, proximally to the site of lesion, into the axillary cavity. According to their “gate-control” theory, the peripheral nerve stimulation produces direct electrical effects by recruitment of primary afferent A-beta and A-delta fibres that project at the spinothalamic tract and dorsal columns and A-alpha fibres that cause segmental inhibition through presynaptic inhibitory interneurons. It can be considered as a reasonable treatment of patients suffering from otherwise intractable painful neuropathies of the upper arm.

Surgery

For patients who undergo intractable traumatic neuropathic pain, which is refractory to medication, surgical procedure is advised. The key of surgical procedure is to remove external pressure thus preventing simultaneous proliferation of nerve and fibrous connective tissue and to maintain the dynamic balance of the microenvironment surrounding the injured nerve. Reinnervation of the distal target or translocation from the distal end organ to a site with minimal potential for further stimulation is the usual treatment 53. As for which kind of surgery should be performed, it depends on which particular nerve is injured. Evans et al. 54 combined resection of the neuroma with implantation of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve into the pronator quadratus muscle, which allowed the nerve to be isolated from wrist motion and denervated skin. The efficacy of this treatment modality was examined, follow-up data were obtained on all patients at a mean of 19 months after surgery, and subjective improvement in pain was reported in 12 of the 13 patients 54. Koch and his team 55 suggested the possibility of inhibiting the formation of painful neuromas by nerve transposition into a vein. Balcin 53 compared the two methods of surgical treatment for painful neuroma by transposition of the nerve stump into an adjacent vein or muscle. Compared to their pre-operative levels in the muscle group three and 12 months after surgery, translocation into a vein led to reduced intensity and evaluative levels of pain, as well as improved sensory as assessed by visual analogue scale and McGill pain score. This was associated with an increased level of activity and improved function. Transposition of the nerve stump into an adjacent vein is preferred to relocation into a muscle. Recently, Martins 56 analyzed data from seven patients using interdigital neurorrhaphy for treatment of digital neuromas. All patients showed some temporary pain relief after nerve block, and therapeutic results were observed during later follow-up. Their findings indicated that interdigital neurorrhaphy achieved satisfactory improvement of symptoms and hand dysfunction 56. Classical surgeries are mostly used in clinical practice and they can indeed provide a certain treatment efficacy. However, all these treatment modalities do have certain respective limitations in practice, for instance, the method of nerve transposition into a vein requires the existence of a suitable vein for the nerve stump to relocate in. The technique like interdigital neurorrhaphy is technically demanding and sometimes no corresponding nerve to be sutured with.

In recent years, several new surgical strategies for traumatic neuropathic pain have attracted interest. The use of soft tissue 57 and the use of conduits 58 have showed great potential in the treatment of traumatic neuropathic pain. Research has shown that myofibroblasts are highly expressed in the neuroma, it is speculated that myofibroblasts may contribute to pain by contracting the collagen matrix around the sensitive non-myelinated fibers that grow astray to form a neuromatous bulging 59. Krishnan 59 concludes that vascularized soft tissue coverage of painful peripheral nerve neuromas can be an effective, but also a complex method of treatment. All kinds of nerve conduits have been popularized in the treatment of nerve defects for years 60 and they have also been introduced in the management of painful neuromas 61. A research conducted by Marcol et al. 57 found microcrystallic chitosan conduit could efficiently prevent the neuroma formation and traumatic neuropathic pain in a rat sciatic nerve model. Clinically, Peterson et al. 62 also achieved satisfactory outcomes using an acellular dermal matrix conduit in treatment of traumatic neuropathic pain at the wrist. The key of these treatment modalities is to cover or protect the injured nerve stump from physical and chemical stimulation, thus eliminating the external stimuli and keeping the injured nerve stump under a relatively stable environment. Similarly, Gennady 63 demonstrates a minimally invasive neurectomy to treat painful medial branch neuroma, which poses little damage to surrounding tissue and indirectly provides good prognosis. Yan et al 64 used aligned nanofiber conduits in the management of painful neuromas in rat sciatic nerves. They found that aligned nanofiber conduits can significantly facilitate linear nerve regeneration, inhibit neuroma growth, and reduce traumatic neuropathic pain after neurectomy 64. Synthetic conduits can be a promising field in the treatment of traumatic neuropathic pain, as the material science evolves.

In general, resection of the existing neuroma is strongly advised for all the patients with traumatic neuropathic pain 43. Transposition and relocation of the nerve stump into a biological tunnel away from partial compression, for instance, muscles, bones and veins are necessary to assure long term efficacy. Artificial conduits can be used under the circumstances that no suitable biological tunnel can be found. Soft tissues treatment, for instance, flaps and lippofilling can provide better prognosis for those patients with large scale of tissue defect and deep soft tissue injury.

Lastly, for patients with intractable traumatic neuropathic pain refractory to medication and refuse any surgical treatment or have little satisfaction with surgery, physiotherapy as electrostimulation and massage may also be good choices.

- Neuroma resection: Simple neuroma resection tends to have short-term therapeutic effect, together with relapse of neuroma 65.

- Neuroma resection and ethanol injection: Appears to be only effective for patients who only suffer from short pain before operation, one-time nerve injury and one neuroma 66.

- Neuroma resection and targeted nerve implantation (TNI): Such surgical method has been performed many times, and it is speculated to have a great role for prevention and treatment of neuroma 67. Its mechanism is as such: The proximal nerve ending at a secondary motor point is transplanted to an adjacent denervated muscle, and the regenerated axons may bifurcate and enter the myenteric motor nerve branches, so as to prevent formation of traumatic neuroma 67.

Traumatic neuroma prognosis

After digital amputation, 6% of people will develop a neuroma 68. When operated at the time of injury, this can decrease to 1%.

Neuromas are a benign condition, however, it can increase in size, become more painful, become tethered. A neuroma is a painful condition with no other significant symptom or complication. This pain, however, is often so severe that patients have to undergo surgery.

There are no studies that are looking at traumatic neuroma regression. However, there are multiple studies which are looking at acoustic neuroma regression rates, which appear around the 4% mark 69. This action results in some patients having active observation rather than surgery.

References- Rasmussen OC. Painful traumatic neuromas in the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;49:191–5. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90043-2

- Foltán R, Klíma K, Spacková J, Sedý J. Mechanism of traumatic neuroma development. Med Hypotheses. 2008 Oct;71(4):572-6. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.05.010

- Yang J, Wang C, Kao W, Wang Y. Traumatic neuroma of bilateral mental nerve: a case report with literature review. Taiwan J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;21:252–60.

- Li Q, Gao EL, Yang YL, et al. Traumatic neuroma in a patient with breast cancer after mastectomy: a case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:35. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-35

- Cardoso TA, dos Santos KR, Franzotti AM, et al. Traumatic neuroma of the penis after circumcision—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(3):397–9. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153233

- Arribas-Garcia I, Alcala-Galiano A, Gutierrez R, Montalvo-Moreno JJ. Traumatic neuroma of the inferior alveolar nerve: a case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E186–8.

- Jones AV, Franklin CD. An analysis of oral and maxillofacial pathology found in adults over a 30-year period. J Oral Pathol Med. 2006;35:392–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00451.x

- Foltán R, Klíma K, Špačková J, Šedý J. Mechanism of traumatic neuroma development. Med Hypotheses. 2008;71:572–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.05.010

- Kallal CF, Ritto G, Almeida LE, Crofton DJ, Thomas GP. Traumatic neuroma following sagittal split osteotomy of the mandible. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:453–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.10.017

- Tay SC, Teoh LC, Yong FC, Tan SH. The prevention of neuroma formation by diathermy: an experimental study in the rat common peroneal nerve. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2005 Jun;34(5):362-8.

- Eguchi T, Ishida R, Ara H, Hamada Y, Kanai I. A diffuse traumatic neuroma in the palate: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2016;10(1):116. Published 2016 May 11. doi:10.1186/s13256-016-0908-5 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4863315

- Teaching NeuroImages: Posttraumatic neuroma-in-continuity of the right tibial nerve. Sathya Narayanan, Radha Sarawagi. Neurology Jun 2014, 82 (22) e198-e199; DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000472

- v

- Minarelli J, Davis EL, Dickerson A, Moore WC, Mejia JA, Gugala Z, Olmsted-Davis EA, Davis AR. Characterization of neuromas in peripheral nerves and their effects on heterotopic bone formation. Mol Pain. 2019 Jan-Dec;15:1744806919838191

- Ashkar L, Omeroglu A, Halwani F, et al. Post-traumatic neuroma following breast surgery. Breast J. 2013;19(6):671–2. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12186

- Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE. Susceptibility of the superficial sensory branch of the radial nerve to form painful neuromas. J Hand Surg Br. 1984 Feb;9(1):42-5.

- Provost N, Bonaldi VM, Sarazin L, et al. Amputation stump neuroma: ultrasound features. J Clin Ultrasound. 1997;25(2):85–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0096(199702)25:2<85::AID-JCU7>3.0.CO;2-F

- Zochodne DW, Theriault M, Sharkey KA, et al. Peptides and neuromas: calcitonin gene-related peptide, substance P, and mast cells in a mechanosensitive human sural neuroma. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20(7):875–80. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199707)20:7<875::AID-MUS12>3.0.CO;2-R

- Allen KP, Hatanpaa KJ, Lemeshev Y, et al. Intratemporal traumatic neuromas of the facial nerve: evidence for multiple etiologies. Otol Neurotol. 2014;35(2):e69–72. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000136

- Thomas AJ, Bull MJ, Howard AC, et al. Peri operative ultrasound guided needle localisation of amputation stump neuroma. Injury. 1999;30(10):689–91. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(99)00185-0

- Fisher GT, Boswick JA., Jr Neuroma formation following digital amputations. J Trauma. 1983;23(2):136–42. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198302000-00012

- Mathews GJ, Osterholm JL. Painful traumatic neuromas. Surg Clin North Am. 1972;52(5):1313–24. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(16)39843-7

- Lai J, Porreca F, Hunter JC, et al. Voltage-gated sodium channels and hyperalgesia. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:371–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121627

- Dawson LF, Phillips JK, Finch PM, et al. Expression of alpha1-adrenoceptors on peripheral nociceptive neurons. Neuroscience. 2011;175:300–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.064

- Stokvis A, Coert JH, van Neck JW. Insufficient pain relief after surgical neuroma treatment: prognostic factors and central sensitisation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(9):1538–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.05.036

- Li CY, Song YH, Higuera ES, et al. Spinal dorsal horn calcium channel alpha2delta-1 subunit upregulation contributes to peripheral nerve injury-induced tactile allodynia. J Neurosci. 2004;24(39):8494–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2982-04.2004

- Lee MJ, Chung KH, Park JS, Chung H, Jang HC, Kim JW. Multiple endocrine neoplasia Type 2B: early diagnosis by multiple mucosal neuroma and its DNA analysis. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:452–5. doi: 10.5021/ad.2010.22.4.452

- Chander V, Rao RS, Sekhar G, Raja A, Sridevi M. Recurrent diffuse neurofibroma of nose associated with neurofibromatosis Type 1: a rare case report with review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:573–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.169128

- Koutlas IG, Scheithauer BW. Palisaded encapsulated (‘solitary circumscribed’) neuroma of the oral cavity: A review of 55 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2010;4:15–26. doi: 10.1007/s12105-010-0162-x

- Allon I, Allon DM, Hirshberg A, Shlomi B, Lifschitz-Mercer B, Kaplan I. Oral neurovascular hamartoma: a lesion searching for a name. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;41:348–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01101.x

- Hanna SA, Catapano J, Borschel GH. Painful pediatric traumatic neuroma: surgical management and clinical outcomes. Childs Nerv Syst. 2016 Jul;32(7):1191-4. doi: 10.1007/s00381-016-3109-z

- van der Avoort DJ, Hovius SE, Selles RW, van Neck JW, Coert JH. The incidence of symptomatic neuroma in amputation and neurorrhaphy patients. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013 Oct;66(10):1330-4. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.06.019

- Pet MA, Ko JH, Friedly JL, Mourad PD, Smith DG. Does targeted nerve implantation reduce neuroma pain in amputees? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Oct;472(10):2991-3001. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3602-1

- Davis B, Hilgart D, Erickson S, Labroo P, Burton J, Sant H, Shea J, Gale B, Agarwal J. Local FK506 delivery at the direct nerve repair site improves nerve regeneration. Muscle Nerve. 2019 Nov;60(5):613-620. doi: 10.1002/mus.26656

- Guo Q, Wang G, Lin W, Huang Z, Tan Z, Liu L, Huang F. [RESEARCH PROGRESS OF AUTOLOGOUS VEIN NERVE CONDUIT FOR REPAIR OF PERIPHERAL NERVE DEFECT]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2015 Nov;29(11):1446-50.

- Sullivan R, Dailey T, Duncan K, Abel N, Borlongan CV. Peripheral Nerve Injury: Stem Cell Therapy and Peripheral Nerve Transfer. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Dec 14;17(12):2101. doi: 10.3390/ijms17122101

- Koch H, Haas F, Hubmer M, et al. Treatment of painful neuroma by resection and nerve stump transplantation into a vein. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;51(1):45–50. doi: 10.1097/01.SAP.0000054187.72439.57

- Hagenacker T, Ledwig D, Busselberg D. Feedback mechanisms in the regulation of intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) in the peripheral nociceptive system: role of TRPV-1 and pain related receptors. Cell Calcium. 2008;43(3):215–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.05.019

- Flor H. Phantom-limb pain: characteristics, causes, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1(3):182–9. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(02)00074-1

- Fornage BD. Peripheral nerves of the extremities: imaging with US. Radiology. 1988;167(1):179–82. doi: 10.1148/radiology.167.1.3279453

- Adams WR., 2nd Morton’s neuroma. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2010;27(4):535–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cpm.2010.06.004

- Lu C, Sun X, Wang C, Wang Y, Peng J. Mechanisms and treatment of painful neuromas. Rev Neurosci. 2018 Jul 26;29(5):557-566. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2017-0077

- Yao C, Zhou X, Zhao B, Sun C, Poonit K, Yan H. Treatments of traumatic neuropathic pain: a systematic review. Oncotarget. 2017;8(34):57670-57679. Published 2017 Apr 7. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.16917 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5593675

- Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Audette J, et al. Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(3 Suppl):S3–14. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0649

- Dooley DJ, Taylor CP, Donevan S, et al. Ca2+ channel alpha2delta ligands: novel modulators of neurotransmission. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28(2):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.12.006

- Greenfield J, Rea J Jr, Ilfeld FW. Morton’s interdigital neuroma. Indications for treatment by local injections versus surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984 May;(185):142-4.

- Hughes RJ, Ali K, Jones H, et al. Treatment of Morton’s neuroma with alcohol injection under sonographic guidance: follow-up of 101 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(6):1535–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1463

- Leung A, Fallah A, Shukla S. Transcutaneous magnetic stimulation (TMS) in alleviating post-traumatic peripheral neuropathic pain states: a case series. Pain Med. 2014;15(7):1196–9. doi: 10.1111/pme.12426

- Dahl E, Cohen SP. Perineural injection of etanercept as a treatment for postamputation pain. Clin J Pain. 2008 Feb;24(2):172-5. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31815b32c8

- Restrepo-Garces CE, Marinov A, McHardy P, et al. Pulsed radiofrequency under ultrasound guidance for persistent stump-neuroma pain. Pain Pract. 2011;11(1):98–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00398.x

- Davis F. Therapeutic Massage Provides Pain Relief to a Client with Morton’s Neuroma: A Case Report. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork. 2012;5(2):12-9.

- Stevanato G, Devigili G, Eleopra R, Fontana P, Lettieri C, Baracco C, Guida F, Rinaldo S, Bevilacqua M. Chronic post-traumatic neuropathic pain of brachial plexus and upper limb: a new technique of peripheral nerve stimulation. Neurosurg Rev. 2014 Jul;37(3):473-79; discussion 479-80. doi: 10.1007/s10143-014-0523-0

- Balcin H, Erba P, Wettstein R, Schaefer DJ, Pierer G, Kalbermatten DF. A comparative study of two methods of surgical treatment for painful neuroma. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009 Jun;91(6):803-8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B6.22145

- Evans GR, Dellon AL. Implantation of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve into the pronator quadratus for treatment of painful neuroma. J Hand Surg Am. 1994 Mar;19(2):203-6. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(94)90006-x

- Koch H, Hubmer M, Welkerling H, Sandner-Kiesling A, Scharnagl E. The treatment of painful neuroma on the lower extremity by resection and nerve stump transplantation into a vein. Foot Ankle Int. 2004 Jul;25(7):476-81. doi: 10.1177/107110070402500706

- Martins RS, Siqueira MG, Heise CO, Yeng LT, de Andrade DC, Teixeira MJ. Interdigital direct neurorrhaphy for treatment of painful neuroma due to finger amputation. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2015 Apr;157(4):667-71. doi: 10.1007/s00701-014-2288-1

- Marcol W, Larysz-Brysz M, Kucharska M, Niekraszewicz A, Slusarczyk W, Kotulska K, Wlaszczuk P, Wlaszczuk A, Jedrzejowska-Szypulka H, Lewin-Kowalik J. Reduction of post-traumatic neuroma and epineural scar formation in rat sciatic nerve by application of microcrystallic chitosan. Microsurgery. 2011 Nov;31(8):642-9. doi: 10.1002/micr.20945

- Economides JM, DeFazio MV, Attinger CE, Barbour JR. Prevention of Painful Neuroma and Phantom Limb Pain After Transfemoral Amputations Through Concomitant Nerve Coaptation and Collagen Nerve Wrapping. Neurosurgery. 2016 Sep;79(3):508-13. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001313

- Krishnan KG, Pinzer T, Schackert G. Coverage of painful peripheral nerve neuromas with vascularized soft tissue: method and results. Neurosurgery. 2005 Apr;56(2 Suppl):369-78; discussion 369-78. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000156881.10388.d8

- Gaudin R, Knipfer C, Henningsen A, Smeets R, Heiland M, Hadlock T. Approaches to peripheral nerve repair: generations of biomaterial conduits yielding to replacing autologous nerve grafts in craniomaxillofacial surgery. Biomed Res Int. 2016(2016):3856262

- Thomsen L, Bellemere P, Loubersac T, Gaisne E, Poirier P, Chaise F. Treatment by collagen conduit of painful post-traumatic neuromas of the sensitive digital nerve: a retrospective study of 10 cases. Chir Main. 2010(29):255–262.

- Peterson SL, Adham MN. Acellular dermal matrix as an adjunct in treatment of neuropathic pain at the wrist. J Trauma. 2006 Aug;61(2):392-5. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000224139.74143.f9

- Gekht G, Nottmeier EW, Lamer TJ. Painful medial branch neuroma treated with minimally invasive medial branch neurectomy. Pain Med. 2010 Aug;11(8):1179-82. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00851.x

- Yan H, Zhang F, Wang C, Xia Z, Mo X, Fan C. The role of an aligned nanofiber conduit in the management of painful neuromas in rat sciatic nerves. Ann Plast Surg. 2015 Apr;74(4):454-61. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000266

- Guse DM, Moran SL. Outcomes of the surgical treatment of peripheral neuromas of the hand and forearm: a 25-year comparative outcome study. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;71(6):654–8. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182583cf9

- Sturm V, Kroger M, Penzholz H. Problems of peripheral nerve surgery in amputation stump pain and phantom limbs. Chirurg. 1975;46(9):389–91.

- Pet MA, Ko JH, Friedly JL, et al. Does targeted nerve implantation reduce neuroma pain in amputees? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(10):2991–3001. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3602-1

- Vlot MA, Wilkens SC, Chen NC, Eberlin KR. Symptomatic Neuroma Following Initial Amputation for Traumatic Digital Amputation. J Hand Surg Am. 2018 Jan;43(1):86.e1-86.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.08.021

- Huang X, Caye-Thomasen P, Stangerup SE. Spontaneous tumour shrinkage in 1261 observed patients with sporadic vestibular schwannoma. J Laryngol Otol. 2013 Aug;127(8):739-43. doi: 10.1017/S0022215113001266