What are vital signs

Vital signs show how well your body is functioning. They are usually measured at doctor’s offices, often as part of a health checkup, or during an emergency room visit.

Vital signs include:

- Blood pressure, which measures the force of your blood pushing against the walls of your arteries. Blood pressure that is too high or too low can cause problems. Your blood pressure has two numbers. The first number is the pressure when your heart beats and is pumping the blood. The second is from when your heart is at rest, between beats. A normal blood pressure reading for adults is lower than 120/80 and higher than 90/60.

- Heart rate or pulse, which measures how fast your heart is beating. A problem with your heart rate may be an arrhythmia. Your normal heart rate depends on factors such as your age, how much you exercise, whether you are sitting or standing, which medicines you take, and your weight.

- Respiratory rate, which measures your breathing. Mild breathing changes can be from causes such as a stuffy nose or hard exercise. But slow or fast breathing can also be a sign of a serious breathing problem.

- Temperature, which measures how hot your body is. A body temperature that is higher than normal (over 98.6 degrees F) is called a fever.

- Oxygen saturation (SpO2): Oxygen saturation is the fraction of oxygen-saturated hemoglobin relative to total hemoglobin (unsaturated + saturated) in your blood. The human body requires and regulates a very precise and specific balance of oxygen (O2) in the blood. Normal blood oxygen levels in humans are considered 95–100 percent.

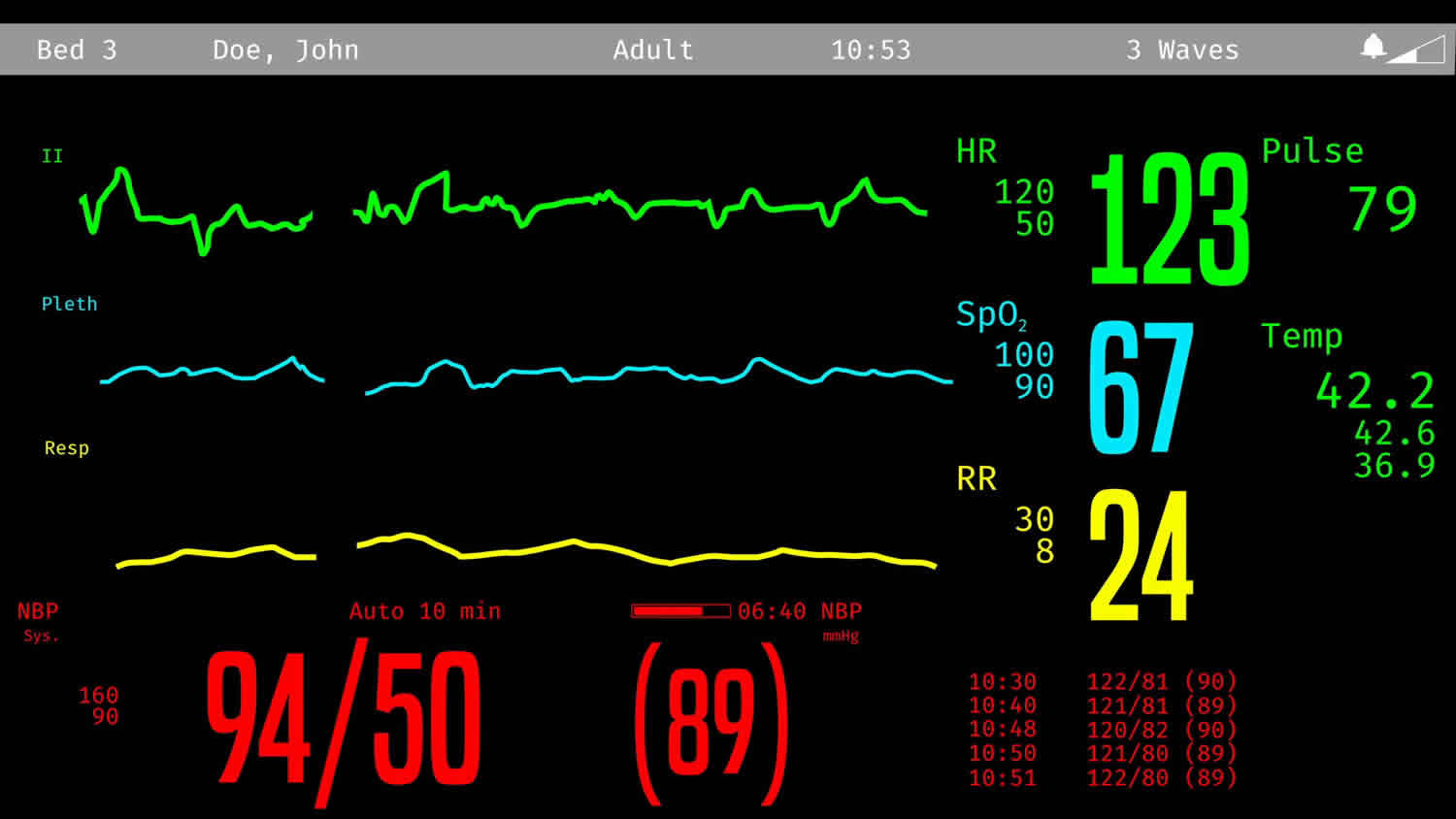

Figure 1. Vital signs monitor

Normal vital signs for adults

- Blood Pressure or BP: The force exerted in the arteries by blood as it circulates; it’s the ratio of systolic (when the heart contracts) and diastolic (when the heart relaxes and fills pressures). Normal blood pressure = near 120/80.

- Heart Rate: The speed of your pulse, measured in beats per minute. Normal heart rate = 60-100.

- Respiratory Rate: Measured by observing the number of times your chest rises and falls in a 60-second period. Normal = 12-16 breaths per minute.

- Temperature or Temp: Measures how hot your body is. Normal = 98.6°F (37°C); greater than 100.4°F (38°C) is considered a fever.

- Oxygen saturation (SpO2): Oxygen saturation is the fraction of oxygen-saturated hemoglobin relative to total hemoglobin (unsaturated + saturated) in your blood. The human body requires and regulates a very precise and specific balance of oxygen (O2) in the blood. Normal blood oxygen levels in humans are considered 95–100 percent. If the level is below 90 percent, it is considered low resulting in hypoxemia. Blood oxygen levels below 80 percent may compromise organ function, such as the brain and heart, and should be promptly addressed. Continued low oxygen levels may lead to respiratory or cardiac arrest.

Blood Pressure

Understanding your blood pressure is critical to your health. There are two numbers used in measuring blood pressure. The high number is known as systolic pressure. The lower number is known as diastolic pressure. Both of the numbers are recorded as “mm Hg” (millimeters of mercury).

High blood pressure (or hypertension) is when the systolic number is equal to or higher than 140 and the diastolic number is equal to or higher than 90. High blood pressure increases the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke.

And while high blood pressure can occur in children and adults, it is more common for those over 35. It is also prevalent in African Americans, obese people, smokers, heavy drinkers, elderly people, women taking birth control pills and those who eat a diet high in fatty and salty foods.

If your blood pressure is extremely high and you are experiencing one or more of the following, contact your primary car physician or go to your local emergency room:

- Chest pain

- Difficulty breathing

- Irregular heartbeat

- Severe headache

- Fatigue or confusion

- Vision problems

- Blood in the urine

Low Blood Pressure (or hypotension) if you feel fine and are able to get up and do your normal activities without difficulty, then there is usually no level at which blood pressure is considered too low. Chronic low blood pressure is almost never serious, but should be checked out by your primary care physician.

A sudden drop in blood pressure, however, can be life-threatening. If you experience a drop in blood pressure due to low or high body temperature, dehydration, bleeding or an allergic reaction, go to your local emergency department immediately.

Heart Rate

To take your pulse, firmly, but gently, press your index and middle finger on the artery at either lower neck, inside your elbow or inside your wrist. When taking your pulse:

- Have a watch with a second hand or a stopwatch so you will know how many beats you count in a minute.

- Start counting the beats when the second hand is on the 12 or when you start your stopwatch.

- Count the beats in a 60-second period. Or, you can count the beats in a 15-second period and multiply that number by four.

- Take your pulse at least twice to get an accurate reading.

- If you are having trouble feeling your pulse, ask another person to count for you.

Below is the American Heart Association’s (AMA) target heart rate chart by age, which is to be used as a guideline.

Table 1. Target Heart Rate Chart by Age

| Age | Target Heart Rate Zone 50–85 % | Average Max Heart Rate 100 % |

| 20 years | 100–170 beats per minute | 200 beats per minute |

| 25 years | 98–166 beats per minute | 195 beats per minute |

| 30 years | 95–162 beats per minute | 190 beats per minute |

| 35 years | 93–157 beats per minute | 185 beats per minute |

| 40 years | 90–153 beats per minute | 180 beats per minute |

| 45 years | 88–149 beats per minute | 175 beats per minute |

| 50 years | 85–145 beats per minute | 170 beats per minute |

| 55 years | 83–140 beats per minute | 165 beats per minute |

| 60 years | 80–136 beats per minute | 160 beats per minute |

| 65 years | 78–132 beats per minute | 155 beats per minute |

| 70 years | 75–128 beats per minute | 150 beats per minute |

Footnote: The AMA notes that a few high blood pressure medications lower the maximum heart rate and, thus, the target zone rate. If you’re taking these types of medicine, call your physician to find out if you need to use a lower target heart rate.

Body Temperature

Taking your temperature

A fever may indicate emergency care is needed. Learn how to best take your temp and what it means.

- Orally. Your temperature can be taken by mouth using a glass or digital thermometer. This method is best for adults and children who are able to do so. Some glass thermometers contain mercury (the silver-colored liquid in the thermometer), which is a toxic and dangerous to humans and the environment. Glass thermometers containing mercury are no longer recommended. According to The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), you must dispose of a mercury thermometer in accordance with local, state, and federal laws. Contact your local health, waste disposal or fire department to learn how. If the glass breaks, do not touch or in particular, vacuum the mercury—call your local poison control center immediately.

- Rectally. You can use a glass of digital thermometer to take a temperature rectally. This method is best for infants under the age of two. Temperatures taken rectally tend to be 0.5 – 0.7° (Fahrenheit) higher than when taken orally.

- Axillary. This method is inaccurate and not relied upon by health care workers. Using a glass or digital thermometer, place it in the armpit. This method is best used on teens and adults, but it is the longest and most inaccurate way of measuring a temperature. Temperatures taken this way tend to be 0.3 – 0.4° (Fahrenheit) lower than those taken orally.

- Aurally. A special thermometer placed in the ear measures the temperature of the eardrum, which indicates your body’s core temperature. This method can be used on anyone over the age of 6 months old and is the quickest way to measure a temperature.

- Temporally. This is a newer method where a device is swiped across the forehead to the temporal area of the scalp (to the side of the eye). It measures the temperature of the blood vessels supplying the skin to that area. It is accurate up to around 99.7° (Fahrenheit). A temperature higher than that should be rechecked with either the oral or rectal method of taking a temperature.

Things to keep in mind

You want to make sure to get the most accurate temperature reading possible. So be sure to:

- Follow the instructions that come with the thermometer.

- Keep your mouth closed around the thermometer when taking your temperature orally.

- Keep the thermometer in place long enough.

- Avoid hot or cold liquids within 30 minutes of taking your temp.

When should you go to the emergency room for a fever?

- Small babies under the age of 3 months old.

- If you are a senior citizen with a fever.

- People who have cancer who are undergoing chemotherapy.

- If you have certain medical problems which make you immunocompromised (i.e. diabetes, sickle cell disease, HIV, etc.)

- If you are taking steroids long-term.

- If the fever lasts for more than 4-5 days.

- If the fever is really high (104° Fahrenheit).

- If the person with the fever looks really ill or has trouble breathing, a change in their behavior, headache or neck stiffness.

Oxygen saturation (SpO2)

Normal pulse oximeter readings usually range from 95 to 100 percent. Values under 90 percent are considered low. Hypoxemia is a below-normal level of oxygen in your blood, specifically in the arteries. Hypoxemia is a sign of a problem related to breathing or circulation, and may result in various symptoms, such as shortness of breath.

Hypoxemia is determined by measuring the oxygen level in a blood sample taken from an artery (arterial blood gas). It can also be estimated by measuring the oxygen saturation of your blood using a pulse oximeter — a small device that clips to your finger.

Normal arterial oxygen is approximately 75 to 100 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). Values under 60 mm Hg usually indicate the need for supplemental oxygen.

Causes of hypoxemia

Several factors are needed to continuously supply the cells and tissues in your body with oxygen:

- There must be enough oxygen in the air you are breathing

- Your lungs must be able to inhale the oxygen-containing air — and exhale carbon dioxide

- Your bloodstream must be able to circulate blood to your lungs, take up the oxygen and carry it throughout your body

A problem with any of these factors — for example, high altitude, asthma or heart disease — might result in hypoxemia, particularly under more extreme conditions, such as exercise or illness. When your blood oxygen falls below a certain level, you might experience shortness of breath, headache, and confusion or restlessness.

Common causes of hypoxemia include:

- Anemia

- ARDS (Acute respiratory distress syndrome)

- Asthma

- Congenital heart defects in children

- Congenital heart disease in adults

- COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)

- Emphysema

- Interstitial lung disease

- Medications, such as certain narcotics and anesthetics, that depress breathing

- Pneumonia

- Pneumothorax (collapsed lung)

- Pulmonary edema (excess fluid in the lungs)

- Pulmonary embolism (blood clot in an artery in the lung)

- Pulmonary fibrosis (scarred and damaged lungs)

- Sleep apnea

Normal vital signs for infants

Table 2. Normal Vital Signs in Newborns Born at 40 Weeks’ Gestation

| Vital sign | Normal range |

|---|---|

| Heart rate | 120 to 160 beats per minute* |

Respiratory rate | 40 to 60 breaths per minute |

Systolic blood pressure | 60 to 90 mm Hg† |

Temperature | 97.7°F to 99.5°F (36.5°C to 37.5°C)‡ |

Weight | Females: 3.5 kg (7 lb, 12 oz); range, 2.8 to 4.0 kg (6 lb, 3 oz to 8 lb, 14 oz) |

Males: 3.6 kg (8 lb); range, 2.9 to 4.2 kg (6 lb, 7 oz to 9 lb, 5 oz) | |

Length | 20 in (51 cm); range, 19 to 21 in (48 to 53 cm) |

Head circumference | 14 in (35 cm); range, 13 to 15 in (33 to 37 cm) |

Footnote:

*—May decrease during sleep.

†—Varies with gestational age.

‡—Overbundling can elevate temperature, thus temperature should be retaken after a period of unbundling. However, not providing appropriate warmth may produce a low temperature. A low temperature may also signify infection or a metabolic or electrolyte abnormality.

[Sources 1, 2, 3 ]Screening for congenital heart disease

Routine screening for congenital heart disease via pulse oximetry is recommended before discharge at 24 hours of life or later, or shortly before discharge if earlier than 24 hours. Newborn screening for critical congenital heart defects can identify newborns with these conditions before signs or symptoms are evident and before the newborns are discharged from the birth hospital. Diagnostic echocardiography should be performed if screening results are positive (Table 3).

Current published recommendations focus on screening newborns in the well-baby nursery and in intermediate care nurseries or other units in which discharge from the hospital is common during a newborn’s first week of life. Timing the screening around the time of the newborn hearing screening can help improve efficiency. A pulse oximeter is used to measure the percentage of hemoglobin in the blood that is saturated with oxygen.

The following algorithm has been developed to show the steps in screening for congenital heart disease via pulse oximetry in newborns 4.

Pulse oximetry screening should not replace taking a complete family health history and pregnancy history or completing a physical examination, which sometimes can detect a critical congenital heart disease before the development of low levels of oxygen (hypoxemia) in the blood.

Screening with pulse oximetry can identify a number of types of critical congenital heart defect, the most common of which are shown in the box below. While not the main targets of screening, many conditions other than critical congenital heart defect may present with hypoxmia and thus likewise be detected via pulse oximetry.

Figure 2. Screening for congenital heart disease using pulse oximetry in newborns

Footnote: Percentages refer to oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximeter.

Footnote: Percentages refer to oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximeter.

Table 3. Pulse Oximetry to Screen Newborns for Congenital Heart Disease

| Timing | Pulse oximetry reading | Interpretation | Next steps |

|---|---|---|---|

24 hours of life or later (or shortly before discharge, if earlier) | ≥ 95% in right hand or foot, with 3% or less absolute difference in oxygen saturation between the right hand and foot | Negative screening result | Plan for discharge |

24 hours of life or later (or shortly before discharge, if earlier) | 90% to 94% in right hand or foot, or 3% or less absolute difference in oxygen saturation between the right hand and foot | Repeat screening needed in one hour | If repeat results are in this range, repeat screening again in one hour; three readings in this range warrant echocardiography |

24 hours of life or later (or shortly before discharge, if earlier) or on repeat screening | < 90% in right hand or foot | Positive screening result | Echocardiography |

Footnote: Guidelines are for newborns in the well-baby nursery.

[Sources 6, 7 ]Failed Screens

A screen is considered failed if:

- Any oxygen saturation measure is <90% (in the initial screen or in repeat screens),

- Oxygen saturation is <95% in the right hand and foot on three measures, each separated by one hour, or

- A >3% absolute difference exists in oxygen saturation between the right hand and foot on three measures, each separated by one hour.

Any infant who fails the screen should have an evaluation for causes of hypoxemia. In most cases this will include an echocardiogram, but if a reversible cause of hypoxemia is identified and appropriately treated, an echocardiogram may not be necessary. The infant’s pediatrician should be notified immediately and the infant might need to be seen by a cardiologist.

Critical congenital heart defects:

- Coarctation of the aorta

- Double outlet right ventricle

- Ebstein anomaly

- Hypoplastic left heart syndrome

- Interrupted aortic arch

- Pulmonary atresia

- Single ventricle

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Total anomalous pulmonary venous return

- d-Transposition of the great arteries

- Tricuspid artresia

- Truncus ateriosus

- Other critical congenital heart defects requiring treatment in the first year of life

Other conditions that are not critical congenital heart defects:

- Hemoglobinopathy

- Hypothermia

- Infection, including sepsis

- Lung disease (congenital or acquired)

- Non-critical congenital heart defect

- Persistent pulmonary hypertension

- Other hypoxic conditions not otherwise specified

Passed Screens

Any screening with an oxygen saturation measure that is ≥95% in the right hand or foot with a ≤3% absolute difference between the right hand or foot is considered a passed screen and screening would end. Pulse oximetry screening does not detect all critical congenital heart defects, so it is possible for a baby with a passing screening result to still have a critical congenital heart defect or other congenital heart defect.

Ways to reduce false positive screens

- Screen the newborn while he or she is alert.

- Screen the newborn when he or she is at least 24 hours old.

Normal vital signs for children

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) in children can be estimated by using the appropriate formula:

- Systolic blood pressure (SBP) = 80 + (2 × age in years)

- Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) = 2/3 × systolic blood pressure

Age 1-3 years

- Heart rate: 80 to 150 beats per minute

- Systolic blood pressure: 90 to 105 mmHg

- Diastolic blood pressure: 55 to 70 mmHg

- Respiratory rate: 22 to 30 breaths per minute

Age 3-6 years

- Heart rate: 70 to 120 beats per minute

- Systolic blood pressure: 95 to 110 mmHg

- Diastolic blood pressure: 60 to 75 mmHg

- Respiratory rate: 20 to 24 breaths per minute

Age 6-12 years

- Heart rate: 60 to 110 beats per minute

- Systolic blood pressure: 100 to 120 mmHg

- Diastolic blood pressure: 60 to 75 mmHg

- Respiratory rate: 16 to 22 breaths per minute

Age 12 years+

- Heart rate: 60 to 100 beats per minute

- Systolic blood pressure: 110 to 135 mmHg

- Diastolic blood pressure: 65 to 85 mmHg

- Respiratory rate: 12 to 20 breaths per minute

- Lissauer T. Physical examination of the newborn. In: Martin RJ, Fanaroff AA, Walsh MC, eds. Fanaroff and Martin’s Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine: Diseases of the Fetus and Infant. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011:485.

- Sniderman A. Abnormal head growth. Pediatr Rev. 2010;31(9):382–384.

- Tschudy MM, Arcara KM; Johns Hopkins Hospital. The Harriet Lane Handbook. 19th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Mosby Elsevier; 2012.

- Kemper AR, Mahle WT, Martin GR, Cooley WC, Kumar P, Morrow WR, Kelm K, Pearson GD, Glidewell J, Grosse SD, Lloyd-Puryear M, Howell RR. Strategies for implementing screening for critical congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2011; 128:e1-8. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/early/2011/10/06/peds.2011-1317.full.pdf

- Congenital Heart Defects (CHDs). https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/heartdefects/hcp.html

- Mahle WT, Martin GR, Beekman RH III, Morrow WR; Section on Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery Executive Committee. Endorsement of Health and Human Services recommendation for pulse oximetry screening for critical congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):190–192.

- Screening for Critical Congenital Heart Defects. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/heartdefects/screening.html