What is Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome

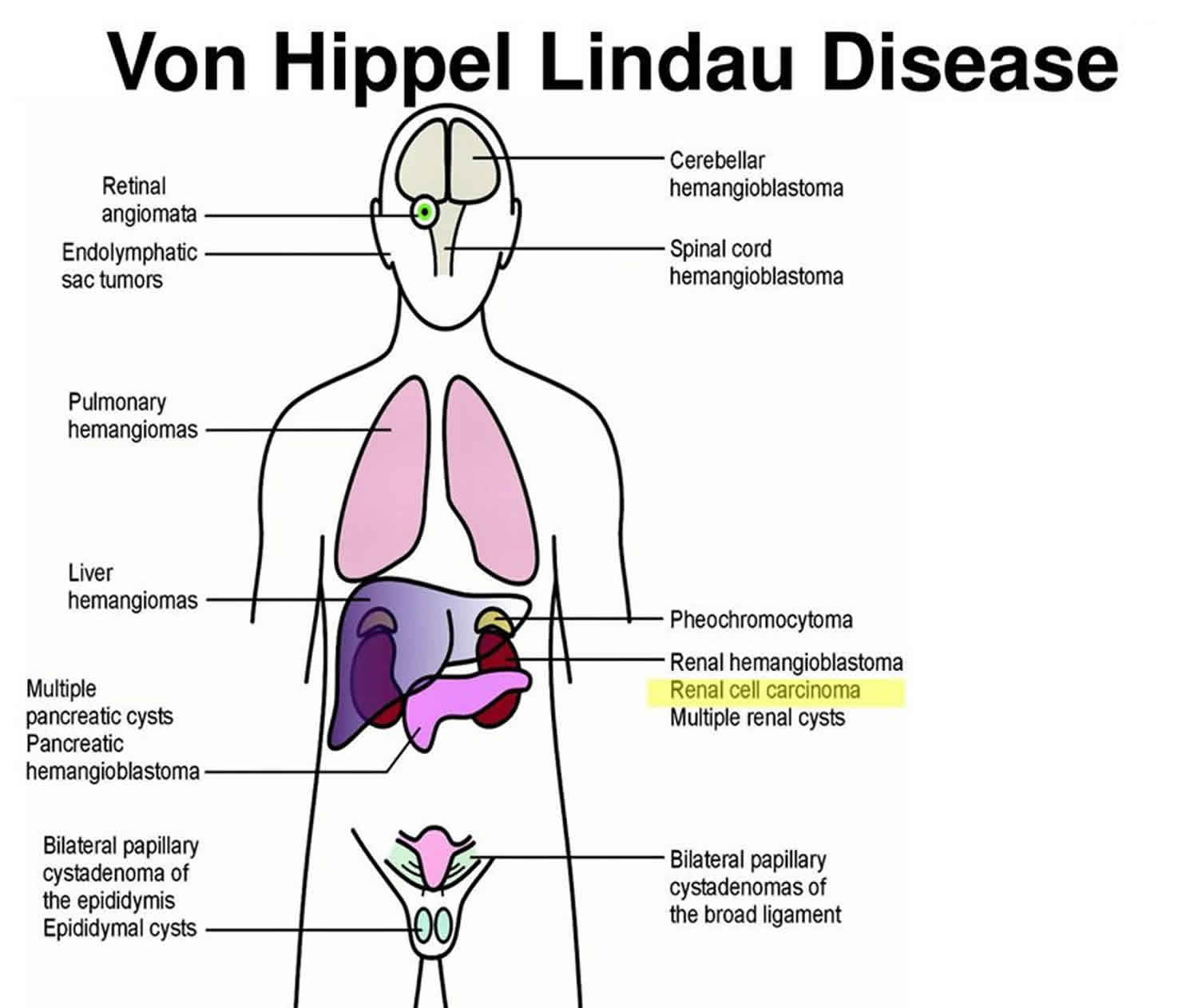

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is a rare inherited disorder characterized by the formation of tumors and fluid-filled sacs (cysts) in many different parts of the body. Tumors may be either noncancerous or cancerous and most frequently appear during young adulthood; however, the signs and symptoms of von Hippel-Lindau syndrome can occur throughout life.

Tumors called hemangioblastomas (blood vessel tumors) are characteristic of von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. These growths are made of newly formed blood vessels. Although they are typically noncancerous, they can cause serious or life-threatening complications. Hemangioblastomas that develop in the brain and spinal cord can cause headaches, vomiting, weakness, and a loss of muscle coordination (ataxia). Hemangioblastomas can also occur in the light-sensitive tissue that lines the back of the eye (the retina). These tumors, which are also called retinal angiomas, may cause vision loss.

People with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome commonly develop cysts in the kidneys, pancreas, and genital tract. They are also at an increased risk of developing a type of kidney cancer called clear cell renal cell carcinoma and a type of pancreatic cancer called a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor.

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is associated with a type of tumor called a pheochromocytoma, which most commonly occurs in the adrenal glands (small hormone-producing glands located on top of each kidney). Pheochromocytomas are usually noncancerous. They may cause no symptoms, but in some cases they are associated with headaches, panic attacks, excess sweating, or dangerously high blood pressure that may not respond to medication. Pheochromocytomas are particularly dangerous in times of stress or trauma, such as when undergoing surgery or in an accident, or during pregnancy.

About 10 percent of people with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome develop endolymphatic sac tumors, which are noncancerous tumors in the inner ear. These growths can cause hearing loss in one or both ears, as well as ringing in the ears (tinnitus) and problems with balance. Without treatment, these tumors can cause sudden profound deafness.

Noncancerous tumors may also develop in the liver and lungs in people with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. These tumors do not appear to cause any signs or symptoms.

The incidence of von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is estimated to be 1 in 36,000 individuals (10,000 cases in the U.S and 200,000 cases worldwide) and 20% of patients are first-in-family or de novo cases. The mean age of onset of 26 years and 97% of people with a Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome gene mutation have symptoms by the age of 65. Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome disease affects males and females and all ethnic groups equally, and occurs in all parts of the world. People who have Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome disease may experience tumors and/or cysts in up to ten parts of the body, including the brain, spine, eyes, kidneys, pancreas, adrenal glands, inner ears, reproductive tract, liver and lung:

- Brain/Spinal Hemangioblastoma Headaches, ataxia, nystagmus, back pain, numbness, hiccups

- Retinal Hemangioblastoma Floaters, retinal detachment

- Endolymphatic Sac Tumor Hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo

- Pancreatic Cysts/Tumor/Cancer Pancreatitis (from blockage of bile ducts), diabetes (from blockage of insulin delivery), digestion irritability, malabsorption, jaundice

- Pheochromocytoma, Paraganglioma High blood pressure, panic attacks (or post-operative adrenal insufficiency)

- Kidney Cysts, Renal Cell Carcinoma Lower back pain, hematuria, fatigue

- Cystadenomas (males and females) Pain: consider rupture, hemorrhage, torsion (possible ovarian cancer)

Most of these Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome tumors are benign, but that does not mean they are problem-free. In fact, benign Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome tumors can still be very serious. As they grow in size, these tumors and the associated cysts can cause an increased pressure on the structure around them. This pressure can create symptoms including severe pain or worse.

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome disease is different in every patient, even within the same family. Since it is impossible to predict exactly how and when the disease will present for each person, it is very important to check regularly for possible Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome manifestations throughout a person’s lifetime.

Currently, a drug (pharmacological) treatment is not available; surgical removal is the method of treatment. An organ sparing approach is the best approach for reducing irreparable damage while minimalizing the need for organ removal. For this reason, Active Surveillance Guidelines (https://www.vhl.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Active-Surveillance-Guidelines.pdf) were developed to make sure Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome tumors can be found and managed appropriately. With careful monitoring, early detection, and appropriate treatment, the most harmful consequences of this gene mutation can be greatly reduced, or in some people, completely prevented.

What causes Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome?

Mutations in the VHL gene located on the short arm of chromosome 3, cause von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. The VHL gene is a tumor suppressor gene, which means it keeps cells from growing and dividing too rapidly or in an uncontrolled way. Mutations in this gene prevent production of the VHL protein or lead to the production of an abnormal version of the protein. An altered or missing VHL protein cannot effectively regulate cell survival and division. As a result, cells grow and divide uncontrollably to form the tumors and cysts that are characteristic of von Hippel-Lindau syndrome.

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome inheritance pattern

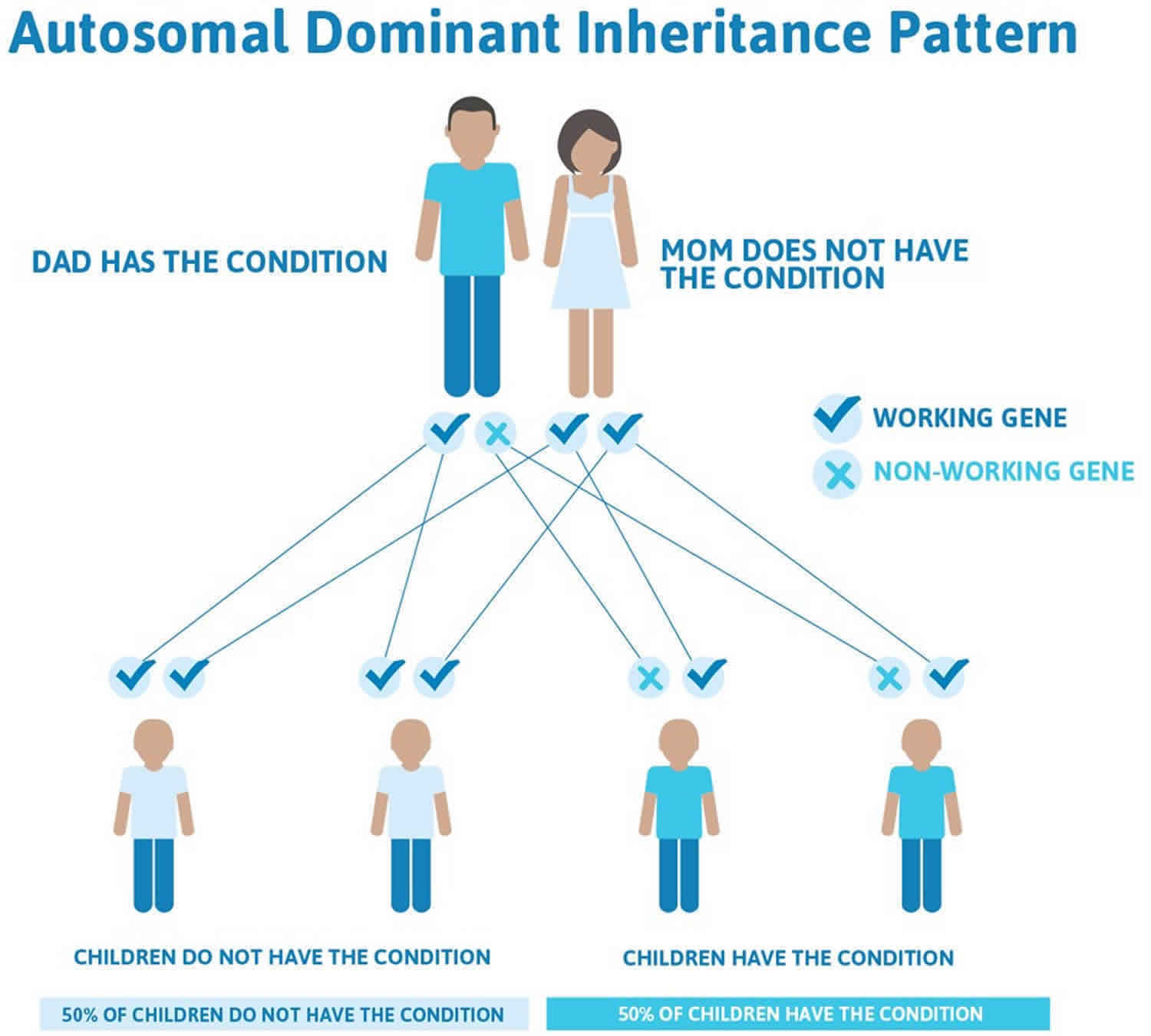

Mutations in the VHL gene are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means that one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to increase the risk of developing tumors and cysts. Most people with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome inherit an altered copy of the gene from an affected parent. In about 20 percent of cases, however, the altered gene is the result of a new mutation that occurred during the formation of reproductive cells (eggs or sperm) or very early in development.

Unlike most autosomal dominant conditions, in which one altered copy of a gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder, two copies of the VHL gene must be altered to trigger tumor and cyst formation in von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. A mutation in the second copy of the VHL gene occurs during a person’s lifetime in certain cells within organs such as the brain, retina, and kidneys. Cells with two altered copies of this gene do not make functional VHL protein, which allows tumors and cysts to develop. Almost everyone who inherits one VHL mutation will eventually acquire a mutation in the second copy of the gene in some cells, leading to the features of von Hippel-Lindau syndrome.

Figure 1. Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome symptoms

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome does not have a single primary symptom. This is in part because it does not occur exclusively in one organ of the body. It also does not always occur in a particular age group. The condition is hereditary, but the presentation of the disease can be very different between individuals, despite the same genetic mutation. In addition, the appearance and severity of Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome lesions are so different between people that many members of the same family may have only some relatively harmless issue, while others may have a serious illness.

Age of onset varies from family to family and from individual to individual. Pheochromocytomas (adrenal tumors) are very common in some families, while clear cell renal cell carcinomas (kidney tumors) are more common in other families.

Symptoms of Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome depend on the size and location of the tumors. They may include:

- Headaches

- Problems with balance and walking

- Dizziness

- Weakness of the limbs

- Vision problems

- High blood pressure

The most common symptom of Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is hemangioblastomas. These are benign tumors occurring in the brain, spinal cord, and retina. Hemangioblastomas are benign. In the brain or spinal cord, the hemangioblastoma may, in some cases, be contained within a cyst or fluid-filled sac. The hemangioblastomas, or surrounding cysts may press on nerve or brain tissue and cause symptoms such as headaches, balance problems when walking, or weakness of arms and legs. In the eyes, blood or fluid leakage from hemangioblastomas can interfere with vision. Early detection, careful monitoring of the eyes and prompt treatment are very important to maintain healthy vision.

Early signs of adrenal tumors may be high blood pressure, panic attacks, or heavy sweating. Early signs of pancreatic cysts and tumors may include digestive complaints like bloating, or disturbance of bowel and bladder function. Some of these tumors are benign, while others may become cancerous.

Kidney tumors and cysts (clear cell renal cell carcinoma) may lead to reduced kidney function, but there are usually no symptoms in the early stages. Kidney tumors will metastasize, if not removed, when they reach approximately 3 cm in diameter.

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome may also cause a benign tumor in the inner ear called an endolymphatic sac tumor. If not removed, this tumor can lead to hearing loss in the affected ear as well as balance problems. Less common manifestations of Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome include benign reproductive tract tumors in both men and women. These tumors, however, can lead to impregnation problems or becoming pregnant

Tumors in the liver and lungs are considered non-problematic.

Related disorders

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is a complicated disease, which causes tumors to grow in 10 different parts of the body: kidneys, adrenals, pancreas, brain, spine, retina, inner ears, reproductive tract, liver, and lungs. Because of the multi-organ involvement, the symptoms and manifestations of Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome overlap with a wide range of diseases. These include the following:

- Kidney: sporadic kidney cancer, Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome, hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC), tuberous sclerosis complex, succinate dehydrogenase subunit (SDH)

- Adrenal or pheochromocytoma: succinate dehydrogenase subunit (SDH), multiple endocrine neoplasia 2 syndrome, types A and B (MEN2A and MEN2B)

- Inner ear: Meniere’s disease

- Pancreas: pancreatic cancer

- Retina: retinal hemangioblastomas are unique to Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. The presences of a retina hemangioblastoma leads to a clinical diagnosis of Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome.

- Brain or spine: hemangioblastomas in the brain or spine are different than other forms of brain or spine tumors and as such, their diagnosis is considered criteria for a Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome DNA test. Note that research on other types of brain tumors is not relevant to Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome hemangioblastomas

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome diagnosis

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is suspected when a person has:

- Multiple hemangioblastomas of the brain, spinal cord, or eye, or

- Hemangioblastoma and clear cell kidney cancer, pancreatic cysts, pheochromocytoma, endolymphatic sac tumor, or a epididymal cyst

- In young patients, Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is also suspected with multiple bilateral clear cell renal cell carcinoma, meaning cancer in both kidneys

If a person has a family history of Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, he or she is suspected of also having Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome if the person has any 1 symptom, such as hemangioblastoma, kidney or pancreatic cysts, pheochromocytoma, or kidney cancer. Genetic testing for mutations in the Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome gene is available for people suspected to have Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Nearly all people with Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome will be found to have the genetic mutation once tested.

Anyone with a parent with Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome and most people with a brother or sister with Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome are at a 50% chance of having Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome disease. Anyone with an aunt, uncle, cousin, or grandparent with Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome may also be at risk. The only way to determine for sure that someone does not have an altered Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome gene is through DNA testing. A clinical diagnosis can also be made when a person exhibits a tumor specific to Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome.

Once a Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome diagnosis has been made, it is important to begin surveillance testing early before any symptoms occur. Most Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome lesions are much easier to treat when they are small. A number of possible complications of Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome do not present with symptoms until the problem has developed to a critical level. Treatment may only be able to stop symptoms that have occurred; it is not always possible to reverse the changes and go back to normal.

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome treatment

A universal treatment recommendation does not exist. Treatment options can only be determined by careful evaluation of the individual patient’s total situation—symptoms, test results, imaging studies, and general physical condition. The risk of kidney cancer in families with Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is estimated to be about 40%. The following are offered as general guidelines for possible treatment therapies.

Brain and Spinal Hemangioblastomas

Symptoms related to hemangioblastomas in the brain and spinal cord depend on tumor location, size, and the presence of associated swelling or cysts. Symptomatic lesions grow more rapidly than asymptomatic lesions. Cysts often cause more symptoms than the tumor itself. Once the lesion has been removed, the cyst will collapse. If any portion of the tumor is left in place, the cyst will re-fill. Small hemangioblastomas, which are not symptomatic and are not associated with a cyst, have sometimes been treated with stereotactic radiosurgery, but this is more preventative than a treatment, and long-term results seem to show only marginal benefit. In addition, during the recovery period symptoms may not be reduced.

Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

Careful analysis is required to differentiate between serous cystadenomas and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pancreatic NETs). Cysts and cystadenomas generally do not require treatment. Pancreatic NETs should be rated on size, behavior, and specific genetic mutation.

Renal Cell Carcinoma

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome kidney tumors are often found when they are very small in size and at very early stages of development. A strategy for ensuring that an individual will have a sufficient functioning kidney throughout his or her lifetime begins with careful monitoring and choosing to operate only when tumor size or rapid growth rate suggest the tumor may gain metastatic potential (at approximately 3 cm). The technique of kidney-sparing surgery is widely used in this setting. Radio frequency ablation or cryosurgery (cryotherapy) may be considered, especially for smaller tumors at earlier stages. Care must be taken not to injure adjacent structures and to limit scarring which may complicate subsequent surgeries.

Retinal Hemangioblastomas

Small peripheral lesions can be successfully treated with little to no loss of vision using laser. Larger lesions often require cryotherapy. If the hemangioblastoma is on the optic disc, there are few treatment options that will successfully preserve vision.

Pheochromocytomas

Surgical removal is performed after adequate blocking with medication, and laparoscopic partial adrenalectomy is preferred. Vital signs are carefully monitored for at least a week following surgery while the body readjusts to its “new normal.” Special caution is warranted during surgical procedures of any type and during pregnancy and delivery. Even pheochromocytomas that do not appear to be active or causing symptoms should be considered for removal, ideally prior to pregnancy or non-emergency surgery.

Endolymphatic Sac Tumors

Patients who have a tumor or hemorrhage visible on MRI but who can still hear require surgery to prevent a worsening of their condition. Deaf patients with evidence on imaging of a tumor should undergo surgery if other neurological symptoms are present in order to prevent worsening of balance problems. Not all endolymphatic sac tumors are visible with imaging; some are only found during surgery.

Active Surveillance Guidelines

Until a cure is found, surveillance is a patient’s strongest defense to prevent severe Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome complications. Surveillance is the testing of individuals at risk for von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) who do not yet have symptoms, or who are known to have Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome but do not yet have symptoms in a particular area. The unaffected organs should still be screened.

Modifications of surveillance schedules may sometimes be done by physicians familiar with individual patients and with their family history. Once a person has a known manifestation of Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, or develops a symptom, the follow-up plan should be determined with the medical team. More frequent testing may be needed to track the growth of known lesions.

People who have had a DNA test and do not carry the altered VHL gene may be excused from testing. Even with the VHL gene, once an individual has reached the age of sixty and still has no evidence of Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome on these surveillance tests, imaging tests may be reduced to every two years for MRI.

Revisions in this version of the surveillance guidelines for Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome include a change in recommendations from CT to MRI, in order to reduce exposure to radiation for all people. CT should be avoided for all pre-symptomatic people, and should be reserved for occasions when it is truly needed to answer a diagnostic question.

In order to monitor the most critical areas of the brain and spinal cord in the most efficient and cost-effective manner, CNS MRIs should include the brain, cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine. Scans should be ordered as no less than a 1.5T MRI with and without contrast, with thin cuts through the posterior fossa, and attention to inner ear/petrous temporal bone to rule out both endolymphatic sac tumor and hemangioblastomas of the neuraxis.

Regular audiometric tests are included in the surveillance protocol to provide a reference point in case of sign or symptom of hearing loss, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), and/or vertigo (dizziness, loss of balance). If hearing drops, swift action may be required to save hearing.

MRI is the preferred surveillance method for the abdomen. Quality ultrasound may be substituted for MRI of the abdomen no more than once every two years. “Quality” is defined as a machine that produces good quality pictures, with an operator experienced in imaging the organs being studied. The objective is to find even small tumors, which are difficult to identify on ultrasound.

A medical surveillance strategy for affected patients and at-risk relatives is as follows:

- Obtain a medical history and perform a physical examination annually, including blood pressure monitoring.

- Obtain laboratory studies (urine and blood samples) annually, starting at age 2 years; testing consists of urinalysis, urine cytologic examination, 24-hour urinary catecholamine metabolites, CBC count, electrolytes, renal function (BUN, Cr), and plasma catecholamines.

- Perform annual direct and indirect ophthalmoscopic examinations; this is best if begun at age 2 years.

- Perform an audiologic examination at the first sign of hearing problems, vertigo, or tinnitus; in one study of VHL gene mutation carriers, more than 90% of radiologically diagnosed endolymphatic sac tumors were associated with abnormal audiometric findings 1. When abnormalities are found, a T1-weighted MRI of the temporal bone should be performed.

- Perform annual abdominal ultrasonography, beginning in the teenage years, to look for abnormalities in the kidneys, adrenal glands, and/or pancreas; concerning findings warrant further investigation with either CT scan or MRI.

- Perform MRI of the brain and spinal cord every 2-3 years, beginning in the teenage years. This recommendation remains controversial within medical circles because CNS tumors without neurological focality are typically not resected.

Patients comply well with completing these monitoring tests at cited intervals, when the physician communicates directly to the patient or the patient’s caregiver 2. A case manager or a nurse practitioner can be assigned to ensure proper surveillance. Screening can be discontinued for at-risk relatives aged 65 years or older if no abnormalities are found up to this age.

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome prognosis

The prognosis for individuals with Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome depends on then number, location, and complications of the tumors. Untreated, Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome may result in blindness and/or permanent brain damage. With early detection and treatment the prognosis is significantly improved. Death is usually caused by complications of brain tumors or kidney cancer.

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome life expectancy

Owing largely to the high incidence of clear cell renal cell carcinoma associated with Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, the average life expectancy in affected individuals is 49 years 3. However, diligent surveillance enabling early treatment interventions can increase life expectancy.

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome disease is a lifelong condition. However, with appropriate measures, people can effectively manage the Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome and lead full and productive lives.

Early diagnosis, regularly surveillance, appropriate treatment and emotional support, and living a healthy lifestyle are all keys to effectively managing the condition and reducing the negative impacts of any tumors or cysts.

Would the treatment of kidney cancer change if I have Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome?

In general, treatment for kidney cancer is similar regardless of whether a patient has Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. However, there is some evidence about specific Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome considerations regarding surgery. For a person with Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome and kidney cancer, surgery for a kidney tumor is generally considered when a tumor reaches 3 centimeters (cm) in size. Preserving the kidney’s function with the intent of preventing or delaying dialysis is an important part of the current surgical approach to Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, and surgeons generally try to remove kidney tumors while trying to leave as much normal kidney behind as possible (called nephron sparing surgery or partial nephrectomy). Similarly, the main treatment for tumors arising in other organs is also surgery, which is done when the tumor reaches a specific size or causes symptoms.

References- Poulsen ML, Gimsing S, Kosteljanetz M, et al. von Hippel-Lindau disease: surveillance strategy for endolymphatic sac tumors. Genet Med. 2011 Dec. 13(12):1032-41

- Lammens CR, Aaronson NK, Hes FJ, et al. Compliance with periodic surveillance for Von-Hippel-Lindau disease. Genet Med. 2011 Jun. 13(6):519-27

- von Hippel-Lindau Disease. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1219430-overview#a3