What is a wart

Warts are very common growths of the skin caused by infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). A wart is also called a verruca or papilloma and warty lesions may be described as verrucous. Warts usually go away on their own but may take months or even years.

A wart will usually have a flesh colored appearance and the skin forming the wart will be rough.

Warts don’t cause you any harm but some people find them itchy, painful or embarrassing. Warty lesions (verrucas) are more likely to be painful – like standing on a needle.

There are several different types of warts, each with a slightly different appearance:

Cutaneous warts have a hard, keratinous surface. A tiny black dot may be observed in the middle of each scaly spot, due to a thrombosed capillary blood vessel.

- Common warts – these are small, raised areas of skin, usually round (papules), with a rough surface of skin often looking like the top of a cauliflower (known as butcher’s warts) — papillomatous and hyperkeratotic surface ranging in size from 1 mm to larger than 1 cm. These warts often appear on backs of fingers or toes, your hands, around the nails —where they can distort nail growth, elbows and knees.

- Flat or Plane warts – these are flat warts that are usually yellow in color (see Figure 6 below). They are often numerous. They are most common in children and can often spread and group together. Multiple flat-topped, flesh-colored papules are typical. Flat warts distribution is grouped and assymetric, helping to distinguish them from seborrheic keratosis in the adult. Flat warts tend to occur on sun-exposed skin, e.g. the back of the hands, the forehead and shins. It appears the immune suppressive nature of sunlight predisposes to flat wart infection. Shaving (or scratching) the legs or beard area can cause multiple lesions through auto-innoculation. Linear flat warts distribution (pseudo-Koebner response) are common. In some cases, the lesions are brown and resemble nevi (freckles). Flat warts are mostly caused by HPV types 3 and 10.

- Plantar warts (verrucas) are warts that appear on your feet, usually on the sole, heel or toes — include tender inwardly growing and painful ‘myrmecia’ on the sole of the foot, and clusters of less painful mosaic warts. The weight of your body causes the wart to be pushed into the skin so a verruca will usually not be raised like other warts and may even cause some discomfort when walking. You may notice a white area of skin with a tiny black dot in the center. Plantar epidermoid cysts are associated with warts. Persistent plantar warts may rarely be complicated by the development of verrucous carcinoma.

- Filiform warts – filiform warts (finger like) are on a long stalk like a thread that usually appear on your eyelids, armpits or neck. Filiform warts commonly appear on the face. Filiform warts are also described as digitate warts.

- Mosaic warts – these grow in clusters and are most common on your hands and feet.

- Mucosal warts – Oral warts can affect the lips and even inside the cheeks, where they may be called squamous cell papillomas. They are softer than cutaneous warts.

Most warts will usually disappear within two years if left untreated, but they can sometimes cause discomfort and can look unpleasant. Warts are also contagious.

You can treat warts if they bother you, keep coming back or are painful. There are treatments available to buy over-the-counter without prescription from pharmacies and some supermarkets. Please speak to your doctor about other treatment options for warts and verrucas.

See a doctor if:

- you’re worried about a growth on your skin

- you aren’t sure whether the growths are warts

- the growths are bothersome and interfere with activities

- you also have a weakened immune system because of immune-suppressing drugs, HIV/AIDS or other immune system disorders

- you have a wart or verruca that keeps coming back

- you have a very large or painful wart or verruca

- a wart bleeds or changes in how it looks

- you have a wart on your face or genitals

- the growths are painful or change in appearance or color

- you’ve tried treating the warts, but they persist, spread or recur

Are warts contagious?

Yes. Warts are caused by a virus known as the human papilloma virus (HPV) and warts can be spread to other people from contaminated surfaces or through close skin contact. You’re more likely to spread a wart or verruca if your skin is wet or damaged.

It can take months for a wart or verruca to appear after contact with the virus.

Mucosal HPV is spread mainly by direct skin-to-skin contact during vaginal, oral, or anal sexual activity. It’s not spread through blood or body fluids. It can be spread even when an infected person has no visible signs or symptoms.

Anyone who has had sexual contact can get HPV, even if it was only with only one person, but infections are more likely in people who have had many sex partners.

The virus can also be spread by genital contact without sex, but this is not common. Oral-genital and hand-genital spread of some genital HPV types have been reported. And there may be other ways to become infected with HPV that aren’t yet clear.

You DO NOT get HPV from:

- Toilet seats

- Hugging or holding hands

- Swimming in pools or hot tubs

- Sharing food or utensils

- Being unclean

Transmission from mother to newborn during birth is rare, but it can happen, too. When it does, it can cause warts (papillomas) in the infant’s breathing tubes (trachea and bronchi) and lungs, which is called respiratory papillomatosis. These papillomas can also grow in the voice box, which is called laryngeal papillomatosis. Both of these infections can cause life-long problems.

DO

- wash your hands after touching a wart or verruca

- change your socks daily if you have a verruca

- cover warts and verrucas with a plaster when swimming

- take care not to cut a wart when shaving

DON’T

- share towels, flannels, socks or shoes if you have a wart or verruca

- bite your nails or suck fingers with warts on

- walk barefoot in public places if you have a verruca

- scratch or pick a wart

Warts are particularly common in:

- School-aged children, but they may arise at any age

- Eczema (dermatitis), due to a defective skin barrier

- People who are immune suppressed with medications such as azathioprine or cyclosporin, or with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. In these patients, the warts may never disappear — despite treatment.

What is a human papillomavirus (HPV)?

Human papillomaviruses (HPV) are a large family of species-specific related double-stranded DNA viruses. There are more than 200 different HPV types; at least 40 can infect the anogenital area. Other types cause warts on other areas of skin. HPV types are often referred to as “non-oncogenic” (wart-causing) or “oncogenic” (cancer-causing), based on whether they put a person at risk for cancer. The International Agency for Research on Cancer found that 13 HPV types can cause cervical cancer, and at least one of these types can cause cancers of the vulva, vagina, penis, anus, and certain head and neck cancers (specifically, the oropharynx, which includes the back of the throat, base of the tongue and tonsils) 1. The types of HPV that can cause genital warts are not the same as the types that can cause cancer.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) transmission is from direct skin-to-skin contact with apparent or subclinical lesions and contact with genital secretions. Micro-abrasions in the recipient’s skin allow viral access to the basal cells of the epithelium. HPV infects keratinocytes in the skin and epithelial cells in mucosa and stimulates them to proliferate, causing a visible lesion. Most HPV infections are asymptomatic and latent, not developing into visible warts. Subclinical infection may show up on a cervical smear. However some HPV types cause anogenital cancer. These types are also contagious.

Most people who become infected with HPV do not know they have it. Usually, the body’s immune system gets rid of the HPV infection naturally within two years. This is true of both oncogenic (cancer-causing) and non-oncogenic (wart-causing) HPV types. By age 50, at least 4 out of every 5 women will have been infected with HPV at one point in their lives. HPV is also very common in men, and often has no symptoms.

At least 75% of sexually active adults have been infected with at least one type of anogenital HPV at some time in their life.

Every year in the United States, 36,500 people (including women and men) are estimated to be diagnosed with a cancer caused by HPV infection (see Table 1 below). Although cervical cancer is the most well-known of the cancers caused by HPV, there are other types of cancer caused by HPV. HPV vaccination could prevent more than 90% of cancers caused by HPV from ever developing. This is an estimated 33,700 cases in the United States every year 2.

Cervical cancer is the only type of cancer caused by HPV with a recommended screening test for detection at an early stage. The other cancers may not be detected until they cause health problems.

Even with screening, HPV causes 11,000 cases of cervical cancer each year in the United States. Every year, 4,000 women die of cervical cancer.

Figure 1. Human papillomavirus (HPV) types and the problems each group can cause (this diagram shows the different groups of human papillomavirus (HPV) types and the problems each group can cause)

Figure 2. Rates of HPV-associated cancers among women in the United States per year (2015–2019)

Footnotes: The chart above shows rates by age group for HPV-associated cancers in the United States during 2015–2019. The rates shown are the number of women in each age group who were diagnosed with HPV-associated cancer for every 100,000 women. Rates were not shown for some cancer sites and age groups because there were fewer than 16 cases. Data are from population-based cancer registries participating in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and/or the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program for 2015 to 2019, covering 99% of the U.S. population.

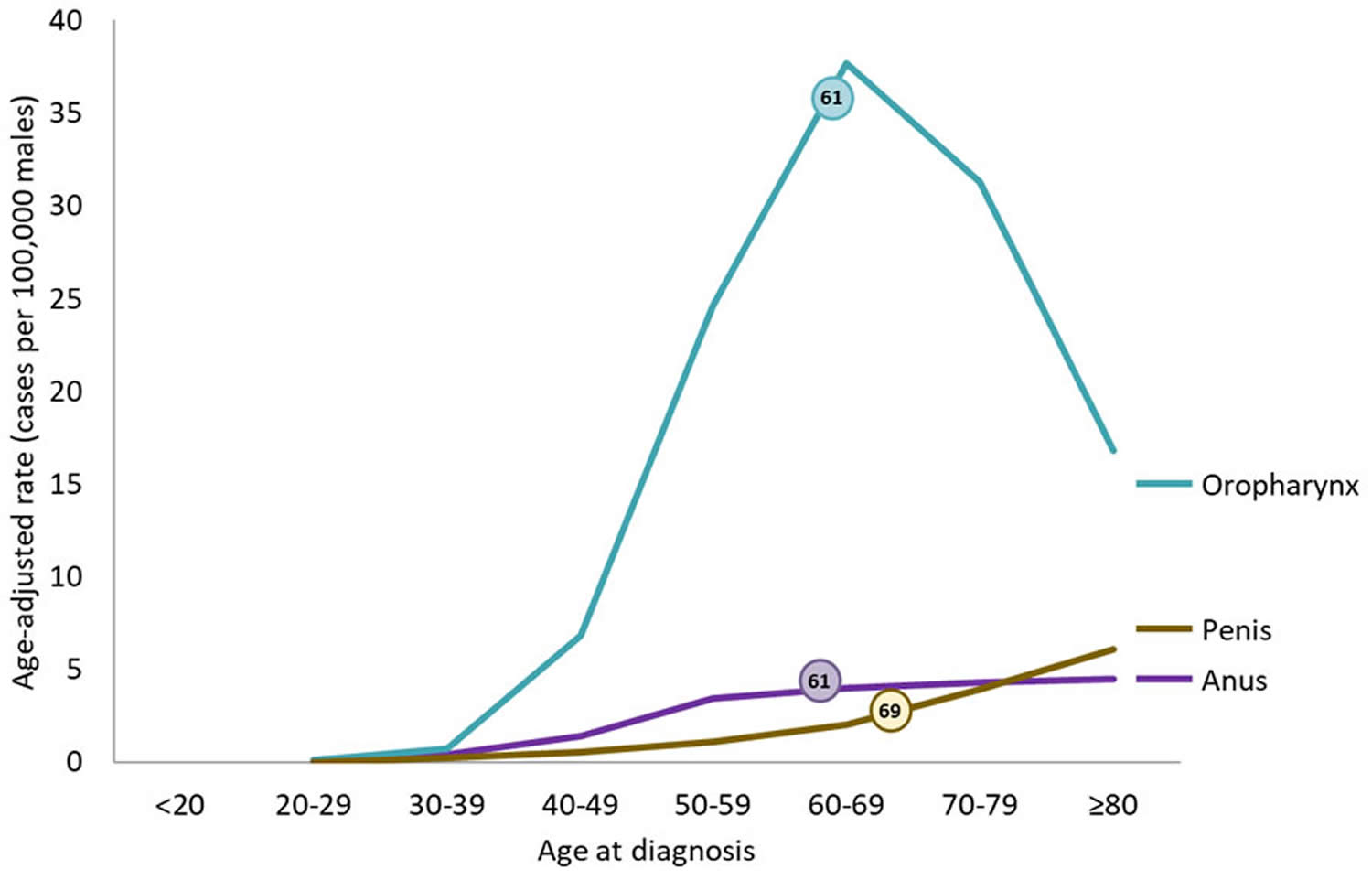

[Source 3 ]Figure 3. Rates of HPV-Associated Cancers and Age at Diagnosis Among Men in the United States per Year (2015–2019)

Footnotes: The chart above shows rates by age group for HPV-associated cancers in the United States during 2015–2019. The rates shown are the number of men who were diagnosed with HPV-associated cancer for every 100,000 men. Rates are not shown for some cancer sites and age groups because there were fewer than 16 cases. Data are from population-based cancer registries participating in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and/or the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program for 2015 to 2019, covering 99% of the U.S. population.

[Source 3 ]Which types of HPV are most likely to cause disease?

In the United States, approximately 80% of HPV-related cancers are attributable to HPV 16 or 18 which are included in all three HPV vaccines that have been available in the U.S. Approximately 12% are attributable to HPV types 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 (16% of all HPV-attributable cancers for females; 6% for males; approximately 3,800 cases annually), which are included in the 9-valent HPV vaccine. HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, or 58 account for about 81% of cervical cancers in the United States. HPV types 6 or 11 cause 90% of anogenital warts (condylomata) and most cases of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis.

How common is human papillomavirus (HPV) infection?

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States. In the United States, an estimated 79 million persons are infected, and an estimated 14 million new HPV infections occur every year among persons age 15 through 59 years. Approximately half of new infections occur among persons age 15 through 24 years. First HPV infection occurs within a few months to years of becoming sexually active.

How serious is disease caused by HPV?

Most HPV infections are asymptomatic and go away completely on their own within 2 years after infection without causing clinical disease. Some infections are persistent and can lead to precancerous lesions or cancer. HPV infection caused by certain HPV types cause almost all cases of anogenital warts in women and men and recurrent respiratory papillomatosis.

From 2014 through 2018, approximately 46,143 new cases of HPV-associated cancers occurred each year in the United States (25,719 among women and 20,424 among men). Cervical cancer, the most widely known HPV-associated cancer, caused an average of 12,200 cases in the U.S. each year during that time. HPV is also associated with vulvar, and vaginal cancer in females, penile cancer in males, and anal and oropharyngeal cancer in both females and males. Between 2014 and 2018, oropharyngeal cancers were the most commonly occurring HPV-associated cancers, with an average of 20,236 reported cases each year (16,680 among men and 3,556 among women).

Table 1. Number of HPV-attributable cancer cases per year in United States

| Cancer site | Average number of cancers per year in sites where HPV is often found (HPV-associated cancers) | Percentage probably caused by any HPV type a | Estimated number probably caused by any HPV type a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cervix | 12293 | 91% | 11100 |

| Vagina | 879 | 75% | 700 |

| Vulva | 4282 | 69% | 2900 |

| Penis | 1375 | 63% | 900 |

| Anus b | 7531 | 91% | 6900 |

| Female | 5106 | 93% | 4700 |

| Male | 2425 | 89% | 2200 |

| Oropharynx | 20839 | 70% | 14800 |

| Female | 3617 | 63% | 2300 |

| Male | 17222 | 72% | 12500 |

| TOTAL | 47199 | 79% | 37300 |

| Female | 26177 | 83% | 21700 |

| Male | 21022 | 74% | 15600 |

Footnotes: Data are from population-based cancer registries participating in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and/or the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program for 2015 to 2019, covering 99% of the U.S. population.

a HPV types detected in genotyping study; most were high-risk HPV types known to cause cancer 4. Estimates were rounded to the nearest 100. Estimated counts might not sum to total because of rounding.

b Includes anal and rectal squamous cell carcinomas.

[Source 5 ]How is HPV transmitted?

Visible anogenital warts and subclinical HPV infection nearly always arise from direct skin to skin contact. Transmission is more likely from visible warts than from subclinical or latent HPV infection. Most new HPV infections occur in adolescents and young adults after their first sexual activity 6. Although most sexually active adults have been exposed to HPV 7, new infections can occur with a new sex partner 8.

- Sexual contact. This is the most common way amongst adults 6.

- Oral sex. HPV appears to prefer the genital area to the mouth.

- Vertical (mother to baby) transmission through the birth canal.

- Auto (self) inoculation from one site to another.

Can HPV be transmitted by non-sexual transmission routes, such as clothing, undergarments, sex toys, or surfaces?

Nonsexual HPV transmission is theoretically possible but has not been definitely demonstrated. This is mainly because HPV can’t be cultured and DNA detection from the environment is difficult and likely prone to false negative results.

If a person has been infected with a wild-type strain of HPV can they be reinfected with the same strain?

- If a person is infected with an HPV strain that does not clear (that is, the person becomes persistently infected) the person cannot be reinfected because they are continuously infected.

- If a person is infected with an HPV strain that clears, some but not all persons will have a lower chance of reinfection with the same strain. Data suggest that females are more likely than males to develop immunity after clearance of natural infection.

- Prior infection with an HPV strain does not lessen the chance of infection with a different HPV strain.

HPV infection prevention

HPV vaccines protect against the types of human papillomavirus (HPV) that most often cause cervical, vaginal, vulvar, penile, and anal precancers and cancers, as well as the types of HPV that cause most oropharyngeal cancers. The vaccine used in the United States also protects against the HPV types that cause most genital warts. Gardasil 9 (9-valent HPV vaccine) is the only HPV vaccine being distributed in the United States 9. Gardasil 9 (9-valent HPV vaccine) is an inactivated 9-valent vaccine licensed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2014. It contains 7 oncogenic (cancer-causing) HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) and two HPV types that cause most genital warts (6 and 11) 10. The 9-valent HPV vaccine is licensed for females and males age 9 through 45 years.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends a routine 2-dose HPV vaccine schedule for adolescents who start the vaccination series before the 15th birthday. The two doses should be separated by 6 to 12 months. The minimum interval between doses is 5 calendar months. A 3-dose schedule is recommended for all people who start the series on or after the 15th birthday and for people with certain immunocompromising conditions (such as cancer, HIV infection, or taking immunosuppressive drugs). The second dose should be given 1 to 2 months after the first dose and the third dose 6 months after the first dose. The minimum interval between the first and second doses of vaccine is 4 weeks. The minimum interval between the second and third doses of vaccine is 12 weeks. The minimum interval between the first and third dose is 5 calendar months. If the vaccination series is interrupted, the series does not need to be restarted.

HPV vaccine (Gardasil 9-valent HPV vaccine) 2-dose schedule:

- A 2-dose schedule is recommended for people who get the first dose before their 15th birthday. In a 2-dose series, the second dose should be given 6–12 months after the first dose (0, 6–12-month schedule).

- The minimum interval is 5 months between the first and second dose. If the second dose is administered after a shorter interval, a third dose should be administered a minimum of 5 months after the first dose and a minimum of 12 weeks after the second dose.

- If the vaccination schedule is interrupted, vaccine doses do not need to be repeated (no maximum interval).

- Immunogenicity studies have shown that two doses of HPV vaccine given to 9–14-year-olds at least 6 months apart provided as good or better protection than three doses given to older adolescents or young adults.

HPV vaccine (Gardasil 9-valent HPV vaccine) 3-dose schedule:

- 3-dose schedule is recommended for people who get the first dose on or after their 15th birthday, and for people with certain immunocompromising conditions.

- In a 3-dose series, the second dose should be given 1–2 months after the first dose, and the third dose should be given 6 months after the first dose (0, 1–2, 6-month schedule).

- The minimum intervals are 4 weeks between the first and second dose, 12 weeks between the second and third doses, and 5 months between the first and third doses. If a vaccine dose is administered after a shorter interval, it should be re-administered after another minimum interval has elapsed since the most recent dose.

- If the vaccination schedule is interrupted, vaccine doses do not need to be repeated (no maximum interval).

HPV vaccination is most effective when offered at a young age, before the onset of sexual activity. However, girls who are already sexually active may not have been infected with the types of HPV covered by the vaccine and may still benefit from vaccination. Women who receive a HPV vaccine should continue to participate in cervical screening programmes.

HPV vaccines are also effective in boys. Vaccination of boys is recommended to reduce transmission of HPV to unvaccinated females. It also reduces the incidence of cancers in males related to HPV infection.

The CDC recommends HPV vaccination for children at ages 11 or 12 years to protect against HPV infections that can cause some cancers later in life 11. HPV vaccination can be started at age 9 and is recommended through age 26 years for those who did not get adequately vaccinated when they were younger.

Side effects from the vaccines are usually mild and include soreness at the injection site, headaches, a low-grade fever or flu-like symptoms.

The CDC now recommends catch-up HPV vaccinations for all people through age 26 who aren’t adequately vaccinated.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently approved the use of Gardasil 9 for males and females ages 9 to 45. If you’re ages 27 to 45, discuss with your doctor whether he or she recommends that you get the HPV vaccine.

If I have been sexually active for a number of years, is it still recommended that I get HPV vaccine or to complete the HPV vaccine series?

Yes. HPV vaccine should be administered to people who are already sexually active. Ideally, patients should be vaccinated before onset of sexual activity; however, people who have already been infected with one or more HPV types will still be protected from other HPV types in the vaccine that have not been acquired.

Are catch-up recommendations for the use of HPV vaccine different for males and females?

No. In June 2019, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted to recommend routine catch-up HPV vaccination of all previously unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated males age 22 through 26, the same as the recommendation for females 12. HPV vaccination recommendations differ by age group. There is one recommendation for people 9 through 26 years of age and another recommendation for people 27 through 45 years of age.

Should transgender persons receive HPV vaccine?

Yes. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends routine HPV vaccination for transgender persons as for all adolescents and young adults through age 26 years. Clinicians should discuss the risks of HPV disease and benefits of HPV vaccination with unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated transgender persons age 27 through 45 years.

What are the recommendations for use of HPV vaccine in people age 27 through 45 years?

Catch-up HPV vaccination is not recommended for all adults older than 26 years of age 10. Instead, shared clinical decision-making (a discussion between the provider and the patient) regarding HPV vaccination is recommended for some adults aged 27 through 45 years who are not adequately vaccinated. Ideally, HPV vaccine should be administered before potential exposure to HPV through sexual contact.

Why is HPV vaccination not routinely recommended for all adults age 27 through 45 years?

Because HPV acquisition generally occurs soon after first sexual activity, HPV vaccine effectiveness will be lower in older age groups as the result of prior infections. In general, exposure to HPV also decreases among individuals in older age groups. Evidence suggests that although HPV vaccination is safe for adults 27 through 45 years, population benefit would be minimal; nevertheless, some adults who are unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated might be at risk for new HPV infection and might benefit from vaccination in this age range.

Do I need revaccination with 9-valent HPV vaccine if I previously received a 3-dose series of 2-valent HPV vaccine or 4-valent HPV vaccine?

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has not recommended routine revaccination with 9-valent HPV vaccine (Gardasil-9) for persons who have completed a 3-dose series of another HPV vaccine. There are data that indicate revaccination with 9-valent HPV vaccine (Gardasil) after a 3-dose series of 4-valent HPV vaccine (quadrivalent Gardasil) is safe. Clinicians should decide if the benefit of immunity against 5 additional oncogenic strains of HPV (which cause 12% of HPV-attributable cancers) is justified for their patients.

Are additional 9-valent HPV vaccine doses recommended for a person who started a 3-dose series with 2-valent HPV vaccine or 4-valent HPV vaccine and completed the series with one or two doses of 9-valent HPV vaccine?

There is no Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendation for additional doses of 9-valent HPV vaccine (Gardasil 9) for persons who started the 3-dose series with 2-valent HPV vaccine (Cervarix) or 4-valent HPV vaccine (quadrivalent Gardasil) and completed the series with 9-valent HPV vaccine (Gardasil 9).

We have several males in our health clinics whose records indicate that they received doses of Cervarix. Can we count these doses as valid?

No. Cervarix (2-valent HPV vaccine) was not approved or recommended for use in males. Doses of Cervarix administered to males should not be counted and need to be repeated using 9-valent HPV vaccine (Gardasil-9).

HPV infection diagnosis

Diagnosis of HPV infection vary by body site and disease manifestation.

History

- Skins warts (verruca vulgaris, verruca plantaris [plantar wart]): Ask about potential infectious contacts and hygiene habits (e.g., “Do you wear shower shoes when showering at the gym?” or “Are the lesions painful and/or prone to bleeding?”)

- Anogenital warts (condyloma acuminata): Healthcare provider should ask about:

- Sexual history/infectious contacts

- Duration and location of the wart(s)

- Prior vaccination for HPV (Gardasil, Cervarix)

- History of wart removal/treatment

- History of diseases or medications that may cause them to be immunocompromised.

- Pap smears (cervical for females, anal Pap smear for males), HPV testing, and sexually transmitted infections.

- Cervical dysplasia (squamous and glandular): Healthcare provider should ask about:

- Menses/prior Pap smears/HPV testing,

- Sexually transmitted infections/sexual history/infectious contacts,

- Prior vaccination for HPV (Gardasil, Cervarix), and

- Associated symptoms, such as bleeding/spotting outside of menses, pelvic or genital pain, pain/bleeding during intercourse, and/or palpable lesions felt on the cervix.

Physical examination

- Skin warts (verruca vulgaris, verruca plantaris): Examine hands and feet thoroughly, including between digits and the underside of the toes.

- Anogenital warts (condyloma acuminata): Examine the anogenital region. Patients may additionally require a speculum examination of the vaginal walls and/or anus. Men may require an examination of the urethra, depending on signs and symptoms. Depending on the history of sexual practices, an oropharyngeal examination may be prudent.

- Cervical dysplasia (squamous and glandular): Perform a speculum examination of the cervix. Depending on the patient’s age and Pap smear history, an initial or repeat Pap smear may be warranted.

Patients with cutaneous, anogenital, and/or oropharyngeal warts may have them excised and submitted for histopathological examination if there is any question about the diagnosis or concern for dysplasia 13, 14.

Screening for cervical dysplasia or cancer is typically accomplished through speculum examination and Pap smear with HPV testing, an assay test performed on cervical cells to evaluate the most common HPV subtypes associated with dysplasia. Treatment protocols stratify patients by age, HPV status, and Pap smear results. Depending on treatment stratification, patients with results concerning intraepithelial squamous or glandular lesions may proceed to colposcopy (a procedure in which the cervix is coated with acetic acid, acetowhite areas are evaluated with a colposcope, and concerning areas are biopsied to examine for histopathologic evidence of dysplasia or malignancy).

HPV infection treatment

There is no treatment for HPV infection. Only HPV-associated lesions including genital warts, recurrent respiratory papillomatosis, precancers, and cancers are treated. Recommended treatments vary depending on the diagnosis, size, and location of the lesion. Local treatment of lesions might not eradicate all HPV containing cells fully; whether available therapies for HPV-associated lesions reduce infectiousness is unclear.

Individuals with skin warts have numerous treatment options available, including surgical removal, cryotherapy (freezing the infected tissue), irritant or immunomodulating medications, and laser removal 15. Many of these treatments’ main goal is to manually or chemically irritate the area, thereby invoking your body’s immune system to assist in clearing the infected tissue 16, 17.

Anogenital and oropharyngeal warts may be treated similarly to skin warts as long as the patient is immunocompetent. Development of HPV-related cancer at these sites may require resection, chemotherapy, and/or radiation 15.

Cervical HPV-driven lesions may regress without any intervention 15. Young immunocompetent women with dysplasia are usually monitored at shortened intervals through Pap smears, HPV testing, and colposcopic examination 15. Persistent cervical dysplasia at any age, or high-grade dysplasia in older women, is treated with cryotherapy, loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), or cold knife cone (CKC) excision. Both surgical procedures (LEEP, CKC) involve resection of the cervical os and transformation zone. If the patient progresses to malignancy (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma, endocervical adenocarcinoma), further resection, chemotherapy, and/or radiation may be required 18, 19.

HPV infection prognosis

The prognosis after an HPV infection is good, but recurrences are common 15. Even though there are many treatments for warts, none works well, and most patients require repeated treatments 15. The HPV infection can also result in vulvar intraepithelial dysplasia, cervical dysplasia, and cervical cancer. Some women remain at high risk for developing vaginal and anal cancer. The risk of malignant transformation is highest in immunocompromised individuals. Finally, when a patient has been diagnosed with HPV infection, there is a 5-20% risk of having other STDs like gonorrhea and/or chlamydia.

What are genital warts?

Genital warts also known as anogenital warts, venereal warts or condyloma acuminata, are one of the most common types of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) passed on by vaginal and anal sex, sharing sex toys and, rarely, by oral sex. Nearly all sexually active people will become infected with at least one type of human papillomavirus (HPV), the virus that causes genital warts, at some point during their lives.

Genital warts affect the moist tissues of the genital area. They can look like small, flesh-colored bumps or have a cauliflower-like appearance. In many cases, the warts are too small to be visible.

Some strains of genital HPV can cause genital warts, while others can cause cancer. An HPV-associated cancer is a specific cellular type of cancer that is diagnosed in a part of the body where HPV is often found. These parts of the body include the cervix, vagina, vulva, penis, anus, rectum, and oropharynx (back of the throat, including the base of the tongue and tonsils) 1, 20. Most anogenital warts are caused by HPV types 6 and 11. The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines can help protect against certain strains of genital HPV 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27.

What are signs and symptoms of genital warts?

In women, anogenital warts can grow on the vulva, the walls of the vagina, the area between the external genitals and the anus, the anal canal, and the cervix. In men, they may occur on the tip or shaft of the penis, the scrotum, or the anus. Rarely, however, genital warts can multiply into large clusters in someone with a good immune system.

Genital warts can also develop in the mouth or throat of a person who has had oral sexual contact with an infected person.

The signs and symptoms of genital warts include:

- Small, flesh-colored, brown or pink swellings in your genital area

- A cauliflower-like shape caused by several warts close together

- Itching or discomfort in your genital area, but often psychological distress is significant

- Bleeding with intercourse

- Distorted urinary stream or bleeding with urethral lesions

- Perianal itch

- Rectal bleeding after passage of stools with anal lesions

- Cervical lesions noted on vaginal examination

Genital warts can be so small and flat as to be invisible.

An anogenital wart is a flesh colored papule with a folded irregular surface a few millimetres in diameter. Warts may join together to form plaques up to several centimetres across. A linear pattern may be seen if the HPV virus has been inoculated along a scratch or tear in the skin.

Genital warts complications

Anogenital warts are contagious and spread particularly to sexual partners. Anogenital warts can enlarge and multiply during pregnancy which may then interfere with vaginal delivery. HPV can be transmitted to the baby resulting in recurrent respiratory papillomatosis in the infant.

HPV infection complications can include:

- Cancer. Cervical cancer has been closely linked with genital HPV infection. Certain types of HPV also are associated with cancers of the vulva, anus, penis, and mouth and throat. However, HPV infection doesn’t always lead to cancer, still it’s important for women to have regular Pap tests (Pap smear), particularly those who’ve been infected with higher risk types of HPV. The Pap test looks for precancers (cell changes on the cervix that might become cervical cancer if they are not treated appropriately).

- Problems during pregnancy. Rarely during pregnancy, warts can enlarge, making it difficult to urinate. Warts on the vaginal wall can inhibit the stretching of vaginal tissues during childbirth. Large warts on the vulva or in the vagina can bleed when stretched during delivery. Extremely rarely, a baby born to a mother with genital warts develops warts in the throat. The baby might need surgery to keep the airway from being blocked.

Anogenital warts can also impact psychosexual functioning and quality of life.

Genital warts and pregnancy

During pregnancy, genital warts:

- can grow and multiply

- might appear for the first time, or come back after a long time of not being there

- can be treated safely, but some treatments should be avoided

- may be removed if they’re very big, to avoid problems during birth

- may be passed to the baby during birth, but this is rare; the HPV virus can cause infection in the baby’s throat or genitals

Most pregnant women with genital warts have a vaginal delivery. Very rarely you might be offered a cesarean, depending on your circumstances.

What causes genital warts?

The human papillomavirus (HPV) causes warts. There are more than 40 strains of HPV that affect the genital area. Genital warts are almost always spread through sexual contact. Your warts don’t have to be visible for you to spread the infection to your sexual partner.

Many people with the human papillomavirus (HPV) do not have symptoms but can still pass it on.

If you have genital warts, your current sexual partners should get tested because they may have warts and not know it.

After you get the infection, it can take weeks to many months before symptoms appear.

You can get genital warts from:

- skin-to-skin contact, including vaginal and anal sex

- sharing sex toys

- oral sex, but this is rare

The HPV virus can also be passed to a baby from its mother during birth, but this is rare.

You cannot get genital warts from:

- kissing

- sharing things like towels, cutlery, cups or toilet seats

Risk factors for getting genital warts

Most people who are sexually active get infected with genital HPV at some time. Factors that can increase your risk of becoming infected include:

- Having unprotected sex with multiple partners

- Having had another sexually transmitted infection

- Having sex with a partner whose sexual history you don’t know

- Becoming sexually active at a young age

- Having a compromised immune system, such as from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or drugs from an organ transplant.

Who gets anogenital warts?

As anogenital warts are usually sexually acquired, they are most commonly observed in young adults between the ages of 15 and 30 years. [see Sexually acquired human papillomavirus] They are highly contagious. However, anogenital warts are rare in people who have been vaccinated against the benign HPV types in childhood before beginning sexual activity. Anogenital warts have been reported in a number of studies to be more common in males than females.

Patients who are immunocompromised due to drug-induced immunosuppression or HIV infection are at particular risk of acquiring HPV and developing anogenital warts.

Anogenital warts can also affect infants and young children. The virus may be acquired during birth or from the hands of carers.

Prevention of genital HPV transmission and genital warts

Limiting your number of sexual partners and being vaccinated with the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine will help prevent you from getting genital warts. Transmission of genital warts to a new sexual partner can be reduced, but not completely prevented by using condoms. Condoms do not prevent all genital skin-to-skin contact, but using a condom every time you have sex is a good idea because they also protect against other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

You can stop genital warts from being passed on by:

- using a condom every time you have vaginal, anal or oral sex – but if the virus is in any in skin that’s not protected by a condom, it can still be passed on

- not having sex while you’re having treatment for genital warts

- not sharing sex toys; if you do share them, wash them or cover them with a new condom before anyone else uses them

HPV vaccination

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends routine HPV vaccination for girls and boys ages 11 and 12, although it can be given as early as age 9. It’s ideal for girls and boys to receive the vaccine before they have sexual contact. The HPV vaccine used in the United States also protects against the HPV types that cause most genital warts. Gardasil 9 (9-valent HPV vaccine) is the only HPV vaccine being distributed in the United States 9. Gardasil 9 (9-valent HPV vaccine) is an inactivated 9-valent vaccine licensed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2014. It contains 7 oncogenic (cancer-causing) HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) and two HPV types that cause most genital warts (6 and 11) 10. The 9-valent HPV vaccine is licensed for females and males age 9 through 45 years.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends a routine 2-dose HPV vaccine schedule for adolescents who start the vaccination series before the 15th birthday. The two doses should be separated by 6 to 12 months. The minimum interval between doses is 5 calendar months. A 3-dose schedule is recommended for all people who start the series on or after the 15th birthday and for people with certain immunocompromising conditions (such as cancer, HIV infection, or taking immunosuppressive drugs). The second dose should be given 1 to 2 months after the first dose and the third dose 6 months after the first dose. The minimum interval between the first and second doses of vaccine is 4 weeks. The minimum interval between the second and third doses of vaccine is 12 weeks. The minimum interval between the first and third dose is 5 calendar months. If the vaccination series is interrupted, the series does not need to be restarted.

HPV vaccine (Gardasil 9-valent HPV vaccine) 2-dose schedule:

- A 2-dose schedule is recommended for people who get the first dose before their 15th birthday. In a 2-dose series, the second dose should be given 6–12 months after the first dose (0, 6–12-month schedule).

- The minimum interval is 5 months between the first and second dose. If the second dose is administered after a shorter interval, a third dose should be administered a minimum of 5 months after the first dose and a minimum of 12 weeks after the second dose.

- If the vaccination schedule is interrupted, vaccine doses do not need to be repeated (no maximum interval).

- Immunogenicity studies have shown that two doses of HPV vaccine given to 9–14-year-olds at least 6 months apart provided as good or better protection than three doses given to older adolescents or young adults.

HPV vaccine (Gardasil 9-valent HPV vaccine) 3-dose schedule:

- 3-dose schedule is recommended for people who get the first dose on or after their 15th birthday, and for people with certain immunocompromising conditions.

- In a 3-dose series, the second dose should be given 1–2 months after the first dose, and the third dose should be given 6 months after the first dose (0, 1–2, 6-month schedule).

- The minimum intervals are 4 weeks between the first and second dose, 12 weeks between the second and third doses, and 5 months between the first and third doses. If a vaccine dose is administered after a shorter interval, it should be re-administered after another minimum interval has elapsed since the most recent dose.

- If the vaccination schedule is interrupted, vaccine doses do not need to be repeated (no maximum interval).

HPV vaccination is most effective when offered at a young age, before the onset of sexual activity. However, girls who are already sexually active may not have been infected with the types of HPV covered by the vaccine and may still benefit from vaccination. Women who receive a HPV vaccine should continue to participate in cervical screening programmes.

HPV vaccines are also effective in boys. Vaccination of boys is recommended to reduce transmission of HPV to unvaccinated females. It also reduces the incidence of cancers in males related to HPV infection.

The CDC recommends HPV vaccination for children at ages 11 or 12 years to protect against HPV infections that can cause some cancers later in life 11. HPV vaccination can be started at age 9 and is recommended through age 26 years for those who did not get adequately vaccinated when they were younger.

Side effects from the vaccines are usually mild and include soreness at the injection site, headaches, a low-grade fever or flu-like symptoms.

The CDC now recommends catch-up HPV vaccinations for all people through age 26 who aren’t adequately vaccinated.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently approved the use of Gardasil 9 for males and females ages 9 to 45. If you’re ages 27 to 45, discuss with your doctor whether he or she recommends that you get the HPV vaccine.

How are genital warts diagnosed?

Anogenital warts are usually diagnosed clinically usually by a doctor in the sexual health clinic. Sexual health clinics specialize in treating problems with the genitals and urine system. Many sexual health clinics offer a walk-in service where you do not need an appointment.

Skin biopsy is sometimes necessary to confirm the diagnosis of viral wart, particularly if there is concern of anogenital cancer.

Pap tests (Pap smear)

For women, it’s important to have regular pelvic exams and Pap tests, which can help detect vaginal and cervical changes caused by genital warts or the early signs of cervical cancer.

During a Pap test, your doctor uses a device called a speculum to hold open your vagina and see the passage between your vagina and your uterus (cervix). He or she will then use a long-handled tool to collect a small sample of cells from the cervix. The cells are examined with a microscope for abnormalities.

HPV test

Only a few types of genital HPV have been linked to cervical cancer. A sample of cervical cells, taken during a Pap test, can be tested for these cancer-causing HPV strains.

In some circumstances, researchers and clinicians may wish to confirm the presence or absence of HPV. One commercially available qualitative test for HPV is the COBAS 4800 Human Papillomavirus (HrHPV) Test, which evaluates 14 high-risk (HR oncogenic) HPV types. This test is generally reserved for women age 30 and older. It isn’t as useful for younger women because for them, HPV usually goes away without treatment.

What is the treatment for genital warts?

If your warts aren’t causing discomfort, you might not need treatment. But if you have itching, burning and pain, or if you’re concerned about spreading the infection, your doctor can help you clear an outbreak with medications or surgery. However, warts often return after treatment. There is no treatment for the virus itself.

Treatment options for genital warts:

- Self-applied treatments at home

- Treatment at a doctor’s surgery or medical clinic.

Self-applied topical treatments

To be successful the patient must identify and reach the warts, and follow the application instructions carefully. Note that treatment is cosmetic rather than curative. Available treatments include:

- Podophyllotoxin solution or cream. Podophyllin is a plant-based resin that destroys genital wart tissue. Never apply podofilox internally. Additionally, this medication isn’t recommended for use during pregnancy. Side effects can include mild skin irritation, sores or pain.

- Patient applied podophyllotoxin paint topically applied, twice a day for 3 days, then 4 days off, repeated weekly for 4-6 cycles until resolution.

- Imiquimod cream (Aldara, Zyclara). Imiquimod cream appears to boost your immune system’s ability to fight genital warts. Avoid sexual contact while the cream is on your skin. It might weaken condoms and diaphragms and irritate your partner’s skin. One possible side effect is skin redness. Other side effects might include blisters, body aches or pain, a cough, rashes, and fatigue.

- Patient applied imiquimod 5% cream topically, 3 times per week at bedtime (wash after 6-10 hours) until resolution (up to 16 weeks).

- Sinecatechins cream (Veregen). Sinecatechins is used for treatment of external genital warts and warts in or around the anal canal. Side effects, such as reddening of the skin, itching or burning, and pain, are often mild.

DON’T try to treat genital warts with over-the-counter wart removers. These medications aren’t intended for use in the genital area.

In HIV infection, genital warts can have a poor response to treatment and may require longer cycles of treatment and are more likely to recur.

Treatments provided at a medical clinic

- Cryotherapy (freezing with liquid nitrogen). Freezing works by causing a blister to form around your wart. As your skin heals, the lesions slough off, allowing new skin to appear. You might need to repeat the treatment. The main side effects include pain and swelling.

- Podophyllin resin. Podophyllin is a plant-based resin that destroys genital wart tissue. Your doctor applies this solution.

- Trichloroacetic acid applications. Trichloroacetic acid is a chemical treatment burns off genital warts, and can be used for internal warts. Side effects can include mild skin irritation, sores or pain.

- Electrosurgery. This procedure uses an electrical current to burn off warts. You might have some pain and swelling after the procedure.

- Curettage and scissor or scalpel excision. You might need surgery to remove larger warts, warts that don’t respond to medications or, if you’re pregnant, warts that your baby can be exposed to during delivery.

- Laser ablation. This approach, which uses an intense beam of light, can be expensive and is usually reserved for extensive and tough-to-treat warts. Side effects can include scarring and pain.

What is the outcome of anogenital warts?

Anogenital warts can resolve spontaneously or in response to treatment. Despite apparent resolution of anogenital warts, the human papillomavirus (HPV) can persist in a latent or subclinical form. Recurrence is therefore very common, particularly in males.

What is a plantar wart?

Plantar wart also called verruca, is a small rough growth on your feet. Plantar warts are caused by the same type of virus, the human papilloma virus (HPV), that causes warts on your hands, fingers and other areas of the body 28, 29. The HPV types most frequently detected on the foot are 1, 2, 4, 10, 27, 57 and 63 30, 31. This virus enters through tiny cuts or breaks on the bottom of the feet. But, because of their location, they can be painful.

Plantar warts usually show up on the balls and heels of the feet, the areas that bear the most pressure. This pressure may also cause a wart to grow inward beneath a hard, thick layer of skin (callus). Furthermore, a plantar wart can commonly be mistaken for a callus or corn. The main difference with a plantar wart is that they tend to “grow in” rather that grow out so can be more painful and harder to treat.

Most plantar warts aren’t a serious health concern and often go away without treatment, especially in children under 12. However, plantar warts are unpredictable and if left untreated may also be transmitted to other people, spread to other areas or become larger. To get rid of them sooner, you can try self-care treatments or see your healthcare provider. Treatments consist of either salicylic acid, cantharidin, bleomycin, intralesional immunotherapy, cryotherapy, laser or surgical excision, but none have been shown to be highly effective in all patients 32.

The aim of most wart treatments is to destroy the affected epidermal cells, through a chemical burn or damage of the wart tissue by applying physical methods, which damages healthy perilesional tissue and causes pain in patients 33. But sometimes the cell damage is not sufficient to destroy the latent virus in adjacent cells 32. As a result, treatments sometimes fail, leading to recalcitrant and recurrent warts 32, 34, 35. This recurrence leads 2% of the general population to seek annual medical attention due to pain and limitation of some activities, aesthetic reasons, and prevention of infections to other areas of the body or other people 32, 36, 37.

Figure 4. Plantar warts

See your doctor for the growth on your foot if:

- The growth is bleeding, painful or changes in shape or color

- You’ve tried treating the wart, but it persists, multiplies or comes back after clearing for a time (recurs)

- Your pain interferes with your activities

- You also have diabetes or poor feeling in your feet

- You also have a weak immune system because of immune-suppressing drugs, HIV/AIDS or other immune system disorders

- You aren’t sure if the growth is a wart

Plantar wart causes

Plantar warts are caused by an infection with HPV in the outer layer of skin on the soles of the feet. The warts develop when the virus enters through tiny cuts, breaks or weak spots on the bottom of the foot. If left untreated, warts can last from a few months to 2 years in children, and several years in in adults.

HPV is very common, and more than 200 kinds of the virus exist. But only a few of them cause warts on the feet. The HPV types most frequently detected on the foot are 1, 2, 4, 10, 27, 57 and 63 30, 31. This virus enters through tiny cuts or breaks on the bottom of the feet. Other types of HPV are more likely to cause warts on other areas of your skin or on mucous membranes.

The HPV strains that cause plantar warts aren’t highly contagious. So the virus isn’t easily spread by direct contact from one person to another. But it thrives in warm, moist places, so you might get the virus by walking barefoot around swimming pools or locker rooms. If the virus spreads from the first site of infection, more warts may grow.

Each person’s immune system responds differently to HPV. Not everyone who comes in contact with it develops warts. Even people in the same family react to the virus differently.

Risk factors for getting plantar warts

Anyone can develop plantar warts, but this type of wart is more likely to affect:

- Children and teenagers

- People with weak immune systems

- People who have had plantar warts before

- People who walk barefoot in areas where a wart-causing virus is common, such as locker rooms, showers and swimming pools

Plantar wart signs and symptoms

Plantar wart signs and symptoms include:

- A small, rough growth on the bottom of your foot, usually at the base of the toes or on the ball or heel

- On brown and Black skin, the growth may be lighter than unaffected skin

- Hard, thickened skin (callus) over a spot on the skin, where a wart has grown inward

- Black pinpoints, which are small clotted blood vessels commonly called wart seeds

- A cluster of growths on the sole of the foot (mosaic warts)

- A growth that interrupts the normal lines and ridges in the skin of your foot

- Pain or tenderness when walking or standing

Plantar wart complications

When plantar warts cause pain, you may alter your normal posture or gait, perhaps without realizing it. Eventually, this change in how you stand, walk or run can cause muscle or joint discomfort.

Plantar wart prevention

To help prevent plantar warts 38:

- Avoid direct contact with warts. This includes your own warts. Wash your hands carefully after touching a wart.

- Keep your feet clean and dry.

- Wear sandals or other foot protection when walking around swimming pools, in locker rooms or in gym showers.

- Don’t pick at or scratch warts.

- When using an emery board, pumice stone or nail clipper on your warts, choose one that you don’t use on your healthy skin and nails.

Plantar wart diagnosis

Your doctor can usually diagnoses a plantar wart by looking at it or cutting off the top layer with a scalpel and checking for dots 39, 40. The dots are tiny clotted blood vessels. Or your health care provider might cut off a small section of the growth and send it to a lab for testing.

Plantar wart treatment

Most plantar warts are harmless and go away without treatment, though it may take a year or two in children, and even longer in adults. If you want to get rid of warts sooner, and self-care approaches haven’t helped, talk with your health care provider.

Using one or more of the following treatments may help:

- Freezing medicine (cryotherapy). Cryotherapy is done in a clinic and involves applying liquid nitrogen to the wart, either with a spray or a cotton swab. This method can be painful, so your health care provider may numb the area first. The freezing causes a blister to form around your wart, and the dead tissue sloughs off within a week or so. Cryotherapy may also stimulate your immune system to fight viral warts. You may need to return to the clinic for repeat treatments every 2 to 3 weeks until the wart disappears. Possible side effects of cryotherapy are pain, blisters and permanent changes in skin color (hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation), particularly in people with brown or Black skin.

- Stronger peeling medicine (salicylic acid). Prescription-strength wart medications with salicylic acid work by removing a wart a layer at a time. They may also boost your immune system’s ability to fight the wart. Your health care provider will likely suggest you apply the medicine regularly at home, followed by occasional office visits. It might take weeks to remove the wart using this method.

A 2011 systematic review and meta‐analysis on the efficacy of topical treatments for skin warts concluded that cryotherapy (cure rate: 45%–75%) should be considered as second‐line treatment with salicylic acid (cure rate: 0%–87%) as the first‐line treatment 41. By contrast, in a recent systematic review, cure rates in plantar warts were found to be higher with cryotherapy (45.61%) than salicylic acid (13.6%) 32. This difference might also be due to the different characteristics of plantar skin and plantar warts 32. Moreover, cure rates with cryotherapy were also higher than with tape (15%) but low compared to other treatments such as cantharidin‐podophylotoxin‐salicylic acid formulation (97.82%), immunotherapy (68.14%), laser (79.36%), topical antivirals (72.45%), and intralesional bleomycin (83.37%) 32. In another recent systematic review of large interventional and observational studies (more than 100 patients per study), the authors concluded that cryotherapy and salicylic acid remain the first‐choice treatments despite having lower efficacy than novel treatments such as laser 42. Other novel treatments, such as intralesional injections including intralesional immunotherapy, are promising but were not represented owing to lack of large studies 42.

Plantar wart removal

If salicylic acid and freezing medicine don’t work, your health care provider may suggest one or more of the following plantar wart removal techniques:

- Minor surgery. Your health care provider cuts away the wart or destroys it by using an electric needle (electrodesiccation and curettage). This method can be painful, so your health care provider will numb your skin first. Because surgery has a risk of scarring, it’s not often used to treat plantar warts unless other treatments have failed. A scar on the sole of the foot can be painful for years.

- Blistering medicine. Your health care provider applies cantharidin, which causes a blister under the wart. You may need to return to the clinic in about a week to have the dead wart clipped off.

- Immune therapy. This method uses medications or solutions to stimulate your immune system to fight viral warts. Your health care provider may inject your warts with a foreign substance (antigen) or apply a solution or cream to the warts.

- Laser treatment. Pulsed-dye laser treatment burns closed (cauterizes) tiny blood vessels. The infected tissue eventually dies, and the wart falls off. This method needs to be repeated every 2 to 4 weeks. Your health care provider will likely numb your skin first.

- HPV vaccine. HPV vaccine has been used with success to treat warts even though this vaccine is not specifically targeted toward the wart viruses that cause plantar warts.

If a plantar wart goes away after treatment and another wart grows, it could be because the area was exposed again to HPV.

No treatment is universally effective at eradicating viral warts. In children, even without treatment, 50% of warts disappear within 6 months, and 90% are gone in 2 years. They are more persistent in adults but they clear up eventually. They are likely to recur in patients that are immune suppressed, e.g, organ transplant recipients. Recurrence is more frequent in tobacco smokers.

Viral warts are very widespread in people with the rare inherited disorder epidermodysplasia verruciformis.

Malignant change is rare in common warts, and causes verrucous carcinoma.

Oncogenic strains of HPV, the cause of some anogenital warts and warts arising in the oropharynx, are responsible for intraepithelial and invasive neoplastic lesions including cervical, anal, penile and vulval cancer.

Figure 5. Warts on hands

Figure 6. Wart on finger

Figure 7. Warts on face

Figure 8. Filiform warts

Figure 9. Wart on foot

Figure 10. Flat warts

Figure 11. Periungual warts are warts about the nails. They are particularly common in children who bite their nails or pick at their cuticles.

What causes warts?

Common warts are caused by an infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV). More than 200 types of human papillomavirus (HPV) exist, but only a few cause warts or papillomas on your hands, which are non-cancerous tumors. The most common subtypes of human papillomavirus (HPV) are types 2, 3, 4, 27, 29, and 57. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is spread by direct skin-to-skin contact or autoinoculation. This means if a wart is scratched or picked, the viral particles may be spread to another area of skin. The incubation period can be as long as twelve months.

Other types of human papillomavirus (HPV) are more likely to cause warts on your feet and other areas of your skin and mucous membranes. Most types of HPV cause relatively harmless conditions such as common warts, while others about 40 of those human papillomavirus (HPV) types affect the genitals and may cause serious disease such as cancer of the cervix. Genital warts are spread through sexual contact (sexually transmitted infections) with an infected partner. Some of those can put you at risk or known to cause cancer, including cancers of the cervix (the base of the womb at the top of the vagina), vagina, vulva (the area around the outside of the vagina), penis, anus, and parts of the mouth and throat. Women are somewhat more likely than men to develop genital warts. Like warts that appear elsewhere on your body, genital warts are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). Some strains of genital HPV can cause genital warts, while others can cause cancer. About 14 million new genital HPV infections occur each year 43. In fact, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that more than 90% and 80%, respectively, of sexually active men and women will be infected with at least one type of HPV at some point in their lives 44. Around one-half of these infections are with a high-risk HPV type 45. Vaccines can help protect against certain strains of genital HPV.

You can get warts from skin-to-skin contact with people who have warts. If you have warts, you can spread the virus to other places on your own body. You can also get the wart virus indirectly by touching something that another person’s wart touched, such as a towel or exercise equipment. The virus usually spreads through breaks in your skin, such as a hangnail or a scrape. Biting your nails also can cause warts to spread on your fingertips and around your nails.

Each person’s immune system responds to the HPV virus differently, so not everyone who comes in contact with HPV develops warts.

Figure 12. Genital warts in mouth

Risk factors for common warts

People at higher risk of developing common warts include:

- Children and young adults

- People with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS or people who’ve had organ transplants.

To reduce your risk of common warts:

- Avoid direct contact with warts. This includes your own warts.

- Don’t pick at warts. Picking may spread the virus.

- Don’t use the same emery board, pumice stone or nail clipper on your warts as you use on your healthy skin and nails.

- Don’t bite your fingernails. Warts occur more often in skin that has been broken. Nibbling the skin around your fingernails opens the door for the virus.

- Groom with care. Use a disposable emery board. And avoid brushing, clipping or shaving areas that have warts. If you must shave, use an electric razor.

- Wash your hands carefully after touching your warts or surfaces such as shared exercise equipment.

HPV is very common, so the only way to keep from becoming infected may be to completely avoid any contact of the areas of your body that can become infected (like the mouth, anus, and genitals) with those of another person. This means not having vaginal, oral, or anal sex, but it also means not allowing those areas to come in contact with someone else’s skin.

HPV vaccines can prevent infection with the types of HPV most likely to cause cancer and genital warts, although the vaccines are most effective when given at a younger age (in older children and teens). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved three vaccines to prevent HPV infection: Gardasil®, Gardasil® 9, and Cervarix®. These vaccines provide strong protection against new HPV infections, but they are not effective at treating established HPV infections or disease caused by HPV 46. Anecdotally, HPV vaccines have been reported to result in clearance of non-genital warts in some people.

If you are sexually active, limiting the number of sex partners and avoiding sexual activity with people who have had many other sex partners can help lower your risk of exposure to genital HPV. But again, HPV is very common, so having sexual contact with even one other person can put you at risk.

Condoms can offer some protection from HPV infection, but HPV might be on skin that’s not covered by the condom. And condoms must be used every time, from start to finish. The virus can spread during direct skin-to-skin contact before the condom is put on, and male condoms don’t protect the entire genital area, especially for women. The female condom covers more of the vulva in women, but hasn’t been studied as carefully for its ability to protect against HPV. Condoms are very helpful, though, in protecting against other infections that can be spread through sexual activity.

It’s usually not possible to know who has a mucosal HPV infection, and HPV is so common that even using these measures doesn’t guarantee that a person won’t get infected, but they can help lower the risk.

Tests are rarely needed to diagnosis viral warts, as they are so common and have a characteristic appearance.

- Pinpoint dots (clotted capillaries) are revealed when the top of the wart is removed.

- Dermatoscopic examination is sometimes helpful to distinguish viral warts from other verrucous lesions such as seborrhoeic keratosis and skin cancer.

- Sometimes, viral warts are diagnosed on skin biopsy. The histopathological features of verruca vulgaris differ from that of plane warts.

How to get rid of warts

Many people don’t bother to treat viral warts because treatment can be more uncomfortable than the warts—they are hardly ever a serious problem. Warts that are very small and not troublesome can be left alone and in some cases they will regress on its own.

However, warts may be painful, and they often look ugly so cause embarrassment.

To get rid of them, you have to stimulate your body’s own immune system to attack the wart virus. Persistence with the treatment and patience is essential!

Topical treatment

Topical treatment includes wart paints containing salicylic acid or similar compounds, which work by removing the dead surface skin cells. Podophyllin is a cytotoxic agent used in some products, and must not be used in pregnancy or in women considering pregnancy.

The paint is normally applied once daily. Treatment with wart paint usually makes the wart smaller and less uncomfortable; 70% of warts resolve within twelve weeks of daily applications.

- Soften the wart by soaking in a bath or bowl of hot soapy water.

- Rub the wart surface with a piece of pumice stone or emery board.

- Apply wart paint or gel accurately, allowing it to dry.

- Covered with plaster or duct tape.

If the wart paint makes the skin sore, stop treatment until the discomfort has settled, then recommence as above. Take care to keep the chemical off normal skin.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy is normally repeated at one to two–week intervals. It is uncomfortable and may result in blistering for several day or weeks. Success is in the order of 70% after 3-4 months of regular freezing.

A hard freeze using liquid nitrogen might cause a permanent white mark or scar. It can also cause temporary numbness.

An aerosol spray with a mixture of dimethyl ether and propane (DMEP) can be purchased over the counter to freeze common and plantar warts. It is important to read and follow the instructions carefully.

Combining Immunotherapy with cryotherapy reduces the number of cryotherapy sessions.

Electrosurgery

Electrosurgery (curettage and cautery) is used for large and resistant warts. Under local anaesthetic, the growth is pared away and the base burned. The wound heals in two weeks or longer; even then 20% of warts can be expected to recur within a few months. This treatment leaves a permanent scar.

Other treatments

Other experimental treatments for recurrent, resistant or extensive warts include:

- Topical retinoids, such as tretinoin cream or adapalene gel

- The immune modulator, imiquimod cream

- Fluorouracil cream

- Bleomycin injections

- Oral retinoids

- Pulsed dye laser destruction of feeding blood vessels

- Photodynamic therapy

- Laser vaporisation

- H2 receptor antagonists

- Oral zinc oxide and zinc sulfate

- Applications of raw garlic or tea tree oil

- Immune stimulation using diphencyprone, squaric acid

- Immunotherapy with Candida albicans or tuberculin PPD

- Hypnosis

- Hyperthermia

- Occlusion with duct tape

Flat wart treatment

- Treatment is not needed. Flat warts have the highest frequency of spontaneous resolution of all warts so observation is appropriate.

- Freezing is okay but caution about color change and that kids don’t like the treatment.

- Sunscreen if in sun-exposed area.

- Tretinoin nightly or imiquimod nightly or alternate the two.

- 5-fluorouricil 5% topically applied twice daily.

- Curettage in appropriate setting.

- Laser therapy

Liquid nitrogen therapy every 1-3 weeks may be performed until all lesions have resolved. If on the legs, cessation of shaving is preferred. If in a sun-exposed area, sun protection is desirable, as it may be that UV suppresses the immune system and prolongs the condition. Topical imiquimod nightly may be tried.

Topical imiquimod every other night alternating with a topical retinoid (e.g., tretinoin) the other nights may be beneficial. Other therapies that have been tried include 5-FU 5% topically applied twice daily for 2-3 weeks. The patient must be informed of all the typical side effects. Topical imiquimod 3 times per week completely cleared the recalcitrant, facial, flat warts after 3 weeks.

Topical immunotherapy with diphenylcyclopropenone was successfully used in one case 47.

Lidocaine followed by light curettage is appropriate and effective in older patients (not young children who don’t like needles), and when the warts are fewer in number. Treatment every 3-4 weeks until gone may be done.

The YAG laser has been employed successfully for flat warts. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) utilises photosensitising agents, oxygen and light, to create a photochemical reaction that selectively destroys cancer cells. Photosensitising agents are drugs that are administered into the body through topical, oral or intravenous methods. In the body, they concentrate in cancer cells and only become active when light of a certain wavelength is directed onto the area where the cancer is. The photodynamic reaction between the photosensitising agent, light and oxygen kills the cancer cells. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is commonly used and 10% ALA (nanoemulsion formulation containing 10% aminolaevulinic acid hydrochloride) is particularly beneficial 48. The pulsed dye laser was used to treat recalcitrant flat, common, plantar/palmar and periungual warts in one study 49. Flat warts were most responsive.

Oral isotretinoin 30 mg/day for 12 weeks cleared all 16 patients (15 placebo) in a randomized, blinded study 50.

Plantar wart removal

How to get rid of plantar warts

- Observation with intermittent paring to prevent pain.

- Salicylic acid

- Cryotherapy

- Lidocaine, then curettage.

- 5-fluorouricil under occlusion

Observation

Plantar warts need not be treated. Plantar warts can be painful depending upon their thickness and location. The patient should be encouraged to do periodic paring if this is the case.

Salicylic Acid

The wart may be treated alone with salicylic acid by the patient/parent. The patient/parent may be told to do the following:

Do the following for any warts NOT on the face or anogenitals: Soak the wart in water for 5-10 minutes and then abrade the surface with e.g., a pumice stone or emery board, to remove the surface white layer. Let dry and then apply two to four drops of 17% salicylic acid (e.g., DuoFilm) directly to the wart once a day. Each drop should be permitted to dry before the next is added. Try to keep the salicylic acid off normal skin. When finished, you can cover with a bandage or duct tape. Repeat daily. If the wart gets significantly inflamed (e.g., red and tender), hold treatment on that lesion and wait to see if the wart goes away. Sometimes when the body succeeds in killing the wart, the wart will suddenly turn black and then fall off in several days.

Alternatively, the application daily of salicylic acid and paring every 2-3 days is a helpful adjunct to cryotherapy. This is because lesions on the soles are driven deep into the skin by the pressure of walking. Removing the hyperkeratotic covering helps expose the wart to therapy. Some suggest the higher the concentration (going as high as 50%), the better. See also combination of SA and imiquimod below in imiquimod section.

Salicylic Acid and 5-Fluorouricil

The combination of 5-Fluorouricil and Salicylic Acid is an effective and beneficial therapy for common and plantar warts 51. WartPeel is one such product.

Paring, Cryotherapy

For these and a variety of other treatment options, see verruca.

Aggressive Curettage

Often, plantar warts are resistant to cryotherapy. One useful technique is to anesthetize first with lidocaine (warn patients that this is painful) and then use a disposable, very sharp curette to core out the wart. Bleeding will occur but can be controlled with light electrocautery or a topical hemostatic agent (e.g., aluminum chloride). Then, a light freeze to the base should be done. This procedure is more aggressive and the patient should agree to the increased pain and longer healing time. S/he should be told of the hole that is created and the potential for limping for a few days. Due to the longer healing time, this procedure may be repeated monthly.

5-Fluorouracil

In a study comparing 5% 5-Fluorouricil cream under tape occlusion versus tape occlusion alone in 40 patients with plantar warts 52, the following was found: “Nineteen out of 20 patients (95%) randomized to 5% 5-FU with tape occlusion had complete eradication of all plantar warts within 12 weeks of treatment. The average time to cure occurred at 9 weeks of treatment. Three patients (15%) had a recurrence at the 6-month follow-up visit; accordingly, an 85% sustained cure rate was observed. It is concluded that use of topical 5% 5-fluorouracil cream for plantar warts is safe, efficacious, and accepted by the patient.”

Adapalene

In a study of 50 patients with 424 plantar warts treated with adapalene gel 0.1% twice daily under occlusion using plastic wrap or weekly cryotherapy 53, the following was found: all the warts in 24 of 25 patients treated with adapalene disappeared in an average of 37 ± 19 days. All the warts in 24 of 25 patients treated with cryotherapy disappeared in 52 ± 30 days in an average of 1.88 sittings of cryo-therapy. During the study, the patients were seen weekly and and it appears from the report that paring was done at those visits. Also, the cryotherapy was performed for 1-2 minutes using an N2O gas operated machine at a temperature of −94°C. The authors postulate that the treatment works by inducing cell-mediated immunity against the wart 54.

Verruca Vulgaris Warts Treatment

- Observe

- Cryotherapy every 1-3 weeks

- Intralesional injection Candida

- Intralesional injection MMR vaccine

- Intralesional injection Vitamin D

- Topical 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) nightly

- Salicylic Acid 17% home treatment (see plantar warts)

- Squaric Acid

- Measure serum zinc level and treat if low.

- Lidocaine followed by curettage, then freezing base (see plantar warts)

- Laser

Observation

No treatment is needed for these benign lesions. However, they are contagious, both to the patient and to others.

Cryotherapy

The mainstay of treatment is cryotherapy performed every 2-3 weeks. A single 10 second freeze seems optimum, based upon studies (see below). A second freeze-thaw added benefit only for plantar warts in one study 55. Waiting more than 3 weeks between treatments allows the wart time to grow back. Two weeks between treatments seems to be optimum for most patients. However, one study of external genital warts 56 found that double freeze-thaw every 7-8 days required fewer sessions and cleared quicker than every 14-21 days.

It is not unusual for the patient to need 6-10 treatments in order to clear the warts. Thus, the patient should be told that one treatment rarely does it–multiple treatments are needed.

Freeze Longer?

An interesting study compared the traditional freeze-thaw (freeze until the wart and a surrounding 1-2 mm halo of normal skin turns white and then stop) to a 10-second freeze (same as traditional, but keep spraying to keep white for 10 seconds) each done every 2 weeks for a maximum of 5 weeks 57. The 10-second freeze was significantly more effective and cleared 64% of non-defaulters compared to 39% in the traditional group. There was more pain, blistering and other side effects, however. Some patients are exquisitely sensitive to cryotherapy and this seems to be idiosyncratic. Thus, perhaps the best approach is to use the traditional method on the first visit and move up to 10 seconds on subsequent visits as tolerated. An alternative published approach is to remove the tip from the cryogun, making it a cryoblast. This increased clearance rates in one study.

Freezing in Children

The use of the spray gun can be frightening to children. A good alternative is to use a cup of the liquid nitrogen to soak a hemostat or forceps for fifteen seconds, then grab the wart for ten seconds. There is no scary spray, nor dripping of the liquid nitrogen (compared with using a cotton-tipped applicator).

Candida Antigen Injection