Cholangiocarcinoma

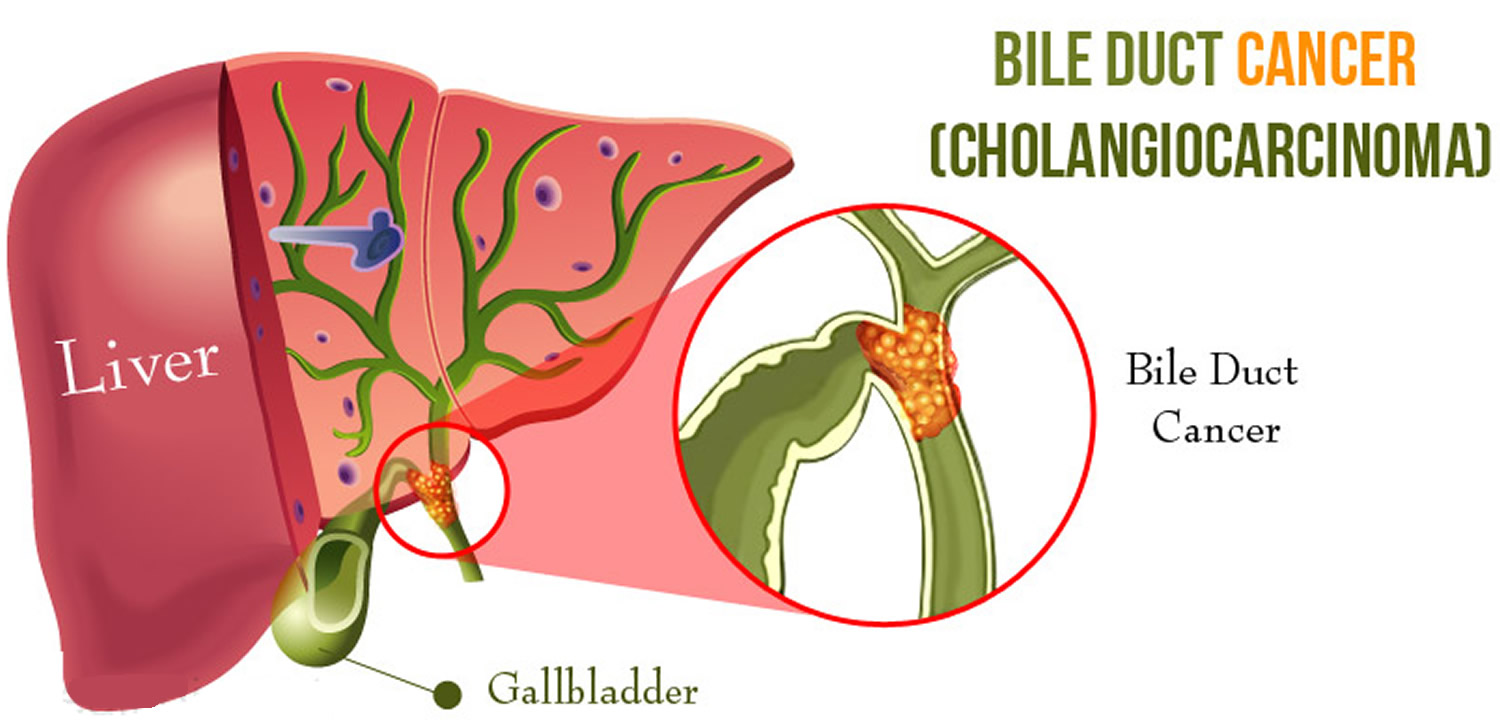

Cholangiocarcinoma also known as bile duct cancer, is a rare type of cancer that mainly affects adults aged over 65, but bile duct cancer can occur at younger ages. A bile duct is a tube that carries bile (fluid made by the liver) between the liver and gallbladder and the small intestine (see Figures 1 to 5). Bile ducts allow fluid called bile to flow from the liver, through the pancreas, to the gut, where it helps with digestion. Cancer can affect any part of these ducts.

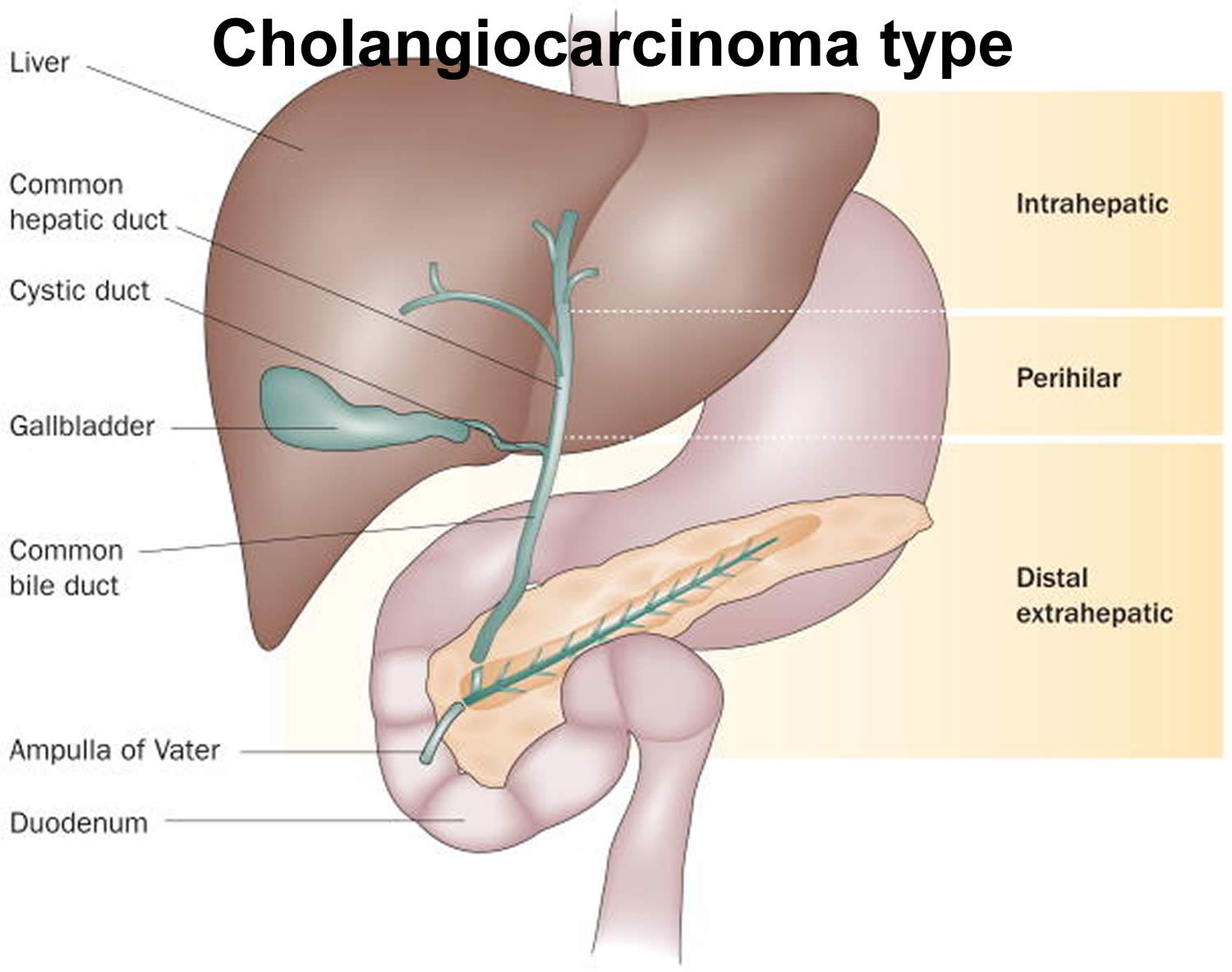

Bile duct cancers can develop in any part of the bile duct system and, based on their location (see Figure 5 below). Doctors divide cholangiocarcinoma into different types based on where the cancer occurs in the bile ducts:

- Intrahepatic bile duct cancers (intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma): grows in the parts of the bile ducts that are in the liver. This is the least common form of cholangiocarcinoma and accounts for only 10% of all cases.

- Perihilar bile duct cancers (hilar cholangiocarcinoma): grows in the bile ducts right outside of the liver. Perihilar bile duct cancer is also called a Klatskin tumor.

- Distal bile duct cancers (distal cholangiocarcinoma): grows in the parts of the bile ducts near the small intestine. Distal bile duct cancer is also called extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Sometimes, hilar cholangiocarcinoma and distal cholangiocarcinoma are grouped together and called extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Bile duct cancers in these different areas can cause different symptoms.

The average age of people in the United States diagnosed with cancer of the intrahepatic bile ducts is 70, and for cancer of the extrahepatic bile ducts it is 72.

Cholangiocarcinoma is rare. On average, it affects fewer than 6 in 100,000 people around the world. In the United States, cholangiocarcinoma affects about 8,000 people per year 1. This includes both intrahepatic (inside the liver) and extrahepatic (outside the liver) bile duct cancers. But the actual number of cases is likely to be higher, as these cancers can be hard to diagnose, and some might be misclassified as other types of cancer. In some places, though, cholangiocarcinoma is more common. For example, in northeast Thailand, cholangiocarcinoma occurs in about 110 per 100,000 people, mostly because a parasitic infection that can cause bile duct cancer is much more common there. In Southeast Asia, the liver fluke Opisthorchis viverrini is the leading cause of cholangiocarcinoma 2. Most people diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma are above the age of 65. Cholangiocarcinoma is slightly more common in men than women.

Most people with cholangiocarcinoma do not have symptoms when it first starts. Later, when the tumor gets larger, cholangiocarcinoma symptoms can include:

- Yellowing of your skin and the whites of your eyes (jaundice)

- Intensely itchy skin

- Unintentional weight loss

- Abdominal pain on the right side, just below the ribs

- White-colored stools

- Dark urine

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Night sweats

The most common symptom of cholangiocarcinoma is jaundice, a yellowing of the skin and eyes, which is caused by a blocked bile duct.

Keep in mind that bile duct cancer is rare. These symptoms are far more likely to be caused by something other than bile duct cancer. For example, people with gallstones have many of these same symptoms. And there are many far more common causes of belly pain than bile duct cancer. Also, hepatitis (an inflamed liver most often caused by infection with a virus) is a much more common cause of jaundice. Still, if you have any of these problems, it’s important to see a doctor right away so the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

If your doctor suspects cholangiocarcinoma, he or she may have you undergo one or more of the following tests:

- Physical exam and health history: A physical exam of the body will be done to check a person’s health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. A history of the patient’s health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.

- Liver function tests: During this procedure a blood sample is checked to measure the amounts of bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase released into the blood by the liver. A higher than normal amount of these substances can be a sign of liver disease that may be caused by bile duct cancer.

- Laboratory tests: These medical tests use samples of tissue, blood, urine, or other substances in the body in order to help diagnose disease, plan and check treatment, or monitor the disease over time.

- Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA 19-9 tumor marker test: Tumor markers are released into the blood by organs, tissues, or tumor cells in the body. Increased levels of CEA and CA 19-9 may be a sign of bile duct cancer.

- Ultrasound exam: This procedure uses high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) that are bounced off internal tissues or organs, such as the abdomen, and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram.

- CT scan (CAT scan): This procedure uses a computer linked to an x-ray machine to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, such as the abdomen, taken from different angles. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): This procedure uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body.

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP): This procedure uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body such as the liver, bile ducts, gallbladder, pancreas, and pancreatic duct.

Different procedures may be used to obtain a sample of tissue and diagnose bile duct cancer. Cells and tissues are removed during a biopsy so they can be viewed under a microscope by a pathologist to check for signs of cancer. The type of procedure used depends on whether you are well enough to have surgery.

Types of biopsy procedures include the following:

- Laparoscopy: This surgical procedure is done to look at the organs inside the abdomen, such as the bile ducts and liver, to check for signs of cancer. Small incisions (cuts) are made in the wall of the abdomen and a laparoscope (a thin, lighted tube) is inserted into one of the incisions. Other instruments may be inserted through the same or other incisions to perform procedures such as taking tissue samples to be checked for signs of cancer.

- Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC): This procedure is used to x-ray the liver and bile ducts. A thin needle is inserted through the skin below the ribs and into the liver. Dye is injected into the liver or bile ducts and an x-ray is taken. A sample of tissue is removed and checked for signs of cancer. If the bile duct is blocked, a thin, flexible tube called a stent may be left in the liver to drain bile into the small intestine or a collection bag outside the body. This procedure may be used when a patient cannot have surgery.

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): This procedure is used to x-ray the ducts (tubes) that carry bile from the liver to the gallbladder and from the gallbladder to the small intestine. Sometimes bile duct cancer causes these ducts to narrow and block or slow the flow of bile, causing jaundice. An endoscope (thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing) is passed through the mouth and stomach and into the small intestine. Dye is injected through the endoscope into the bile ducts and an x-ray is taken. A sample of tissue is removed and checked for signs of cancer. If the bile duct is blocked, a thin tube may be inserted into the duct to unblock it. This tube (or stent) may be left in place to keep the duct open. This procedure may be used when a patient cannot have surgery.

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS): During this procedure an endoscope is inserted into the body, usually through the mouth or rectum. A probe at the end of the endoscope is used to bounce high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. A sample of tissue is removed and checked for signs of cancer. This procedure is also called endosonography.

The chances of survival for patients with bile duct cancer depend to a large extent on its location and how advanced it is when it is found.

Once bile duct cancer has been diagnosed, the prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options depend on the following:

- whether the cancer is in the upper or lower part of the bile duct system

- the stage of the cancer (whether it affects only the bile ducts or has spread to the liver, lymph nodes, or other places in the body)

- whether the cancer has spread to nearby nerves or veins

- whether the cancer can be completely removed by surgery

- whether the patient has other conditions, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis

- whether the level of CA 19-9 is higher than normal

- whether the cancer has just been diagnosed or has recurred (come back)

Your treatment options for biliary tract cancer will depend on several factors:

- The location and extent of the bile duct cancer

- Whether the bile duct cancer is resectable (removable by surgery) or unresectable.

- Resectable, which means they can remove it with surgery.

- Unresectable, which means that surgery to remove the cancer is not possible. The cancer may have grown into nearby organs (locally advanced) or spread elsewhere in the body (advanced).

- The likely side effects of treatment

- Your overall health

- The chances of curing the disease, extending life, or relieving symptoms

To decide about what treatment you need, your doctor and your cancer care team looks at your tests and scan results to see if they can remove (resect) the cancer or not.

The main types of treatment for bile duct cancer include:

- Surgery. When possible, doctors try to remove as much of the cancer as they can. For very small bile duct cancers, this involves removing part of the bile duct and joining the cut ends. For more-advanced bile duct cancers, nearby liver tissue, pancreas tissue or lymph nodes may be removed as well.

- Liver transplant. Surgery to remove your liver and replace it with one from a donor (liver transplant) may be an option in certain cases for people with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. For many, a liver transplant is a cure for hilar cholangiocarcinoma, but there is a risk that the cancer will recur after a liver transplant.

- Chemotherapy. Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy may be used before a liver transplant. It may also be an option for people with advanced cholangiocarcinoma to help slow the disease and relieve signs and symptoms.

- Radiation therapy. Radiation therapy uses high-energy sources, such as photons (x-rays) and protons, to damage or destroy cancer cells. Radiation therapy can involve a machine that directs radiation beams at your body (external beam radiation). Or it can involve placing radioactive material inside your body near the site of your cancer (brachytherapy).

- Photodynamic therapy. In photodynamic therapy, a light-sensitive chemical is injected into a vein and accumulates in the fast-growing cancer cells. Laser light directed at the cancer causes a chemical reaction in the cancer cells, killing them. You’ll typically need multiple treatments. Photodynamic therapy can help relieve your signs and symptoms, and it may also slow cancer growth. You’ll need to avoid sun exposure after treatments.

- Targeted drug therapy. Targeted drug treatments focus on specific abnormalities present within cancer cells. By blocking these abnormalities, targeted drug treatments can cause cancer cells to die. Your doctor may test your cancer cells to see if targeted therapy may be effective against your cholangiocarcinoma.

- Immunotherapy. Immunotherapy uses your immune system to fight cancer. Your body’s disease-fighting immune system may not attack your cancer because the cancer cells produce proteins that help them hide from the immune system cells. Immunotherapy works by interfering with that process. For cholangiocarcinoma, immunotherapy might be an option for advanced cancer when other treatments haven’t helped.

- Heating cancer cells. Radiofrequency ablation uses electric current to heat and destroy cancer cells. Using an imaging test as a guide, such as ultrasound, the doctor inserts one or more thin needles into small incisions in your abdomen. When the needles reach the cancer, they’re heated with an electric current, destroying the cancer cells.

- Biliary drainage. Biliary drainage is a procedure to restore the flow of bile. It can involve bypass surgery to reroute the bile around the cancer or stents to hold open a bile duct being collapsed by cancer. Biliary drainage helps relieve signs and symptoms of cholangiocarcinoma.

- Clinical trials. Clinical trials are studies to test new treatments, such as new drugs and new approaches to surgery. If the treatment being studied proves to be safer and more effective than are current treatments, it can become the new standard of care. Clinical trials can’t guarantee a cure, and they might have serious or unexpected side effects. On the other hand, cancer clinical trials are closely monitored to ensure they’re conducted as safely as possible. They offer access to treatments that wouldn’t otherwise be available to you. Talk to your doctor about what clinical trials might be appropriate for you.

- Palliative therapy.Palliative care is specialized medical care that focuses on providing relief from pain and other symptoms of a serious illness. Palliative care specialists work with you, your family and your other doctors to provide an extra layer of support that complements your ongoing care. Palliative care can be used while undergoing aggressive treatments, such as surgery.When palliative care is used along with other appropriate treatments — even soon after your diagnosis — people with cancer may feel better and may live longer.Palliative care is provided by teams of doctors, nurses and other specially trained professionals. These teams aim to improve the quality of life for people with cancer and their families. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care or end-of-life care.

Treatment options may also depend on the symptoms caused by the cancer. Bile duct cancer is usually found after it has spread and can rarely be completely removed by surgery. Palliative therapy may relieve symptoms and improve the patient’s quality of life.

Bile duct cancer can sometimes be cured if caught very early on, but it’s not usually picked up until a later stage, when a cure isn’t possible.

How long can you live with bile duct cancer?

The prognosis for bile duct cancer depends on which part of the bile duct is affected and how far the cancer has grown.

Even if it’s possible to remove the cancer, there’s a chance it could come back later.

Overall:

- One in every two to five people (20-50%) will live at least five years if bile duct cancer is caught early on and surgery is carried out to try to remove it

- One in every 50 people (2%) will live at least five years if it’s caught at a later stage and surgery to remove it isn’t possible.

Can bile duct cancer be found early?

Only a small number of bile duct cancers are found before they have spread too far to be removed by surgery.

The bile ducts are deep inside the body, so early tumors can’t be seen or felt during routine physical exams. There are no blood tests or other tests that can reliably detect bile duct cancers early enough to be useful as screening tests. (Screening is testing for cancer in people without any symptoms.) Because of this, most bile duct cancers are found only after the cancer has grown enough to cause signs or symptoms. The most common symptom is jaundice, a yellowing of the skin and eyes, which is caused by a blocked bile duct.

Bile ducts anatomy

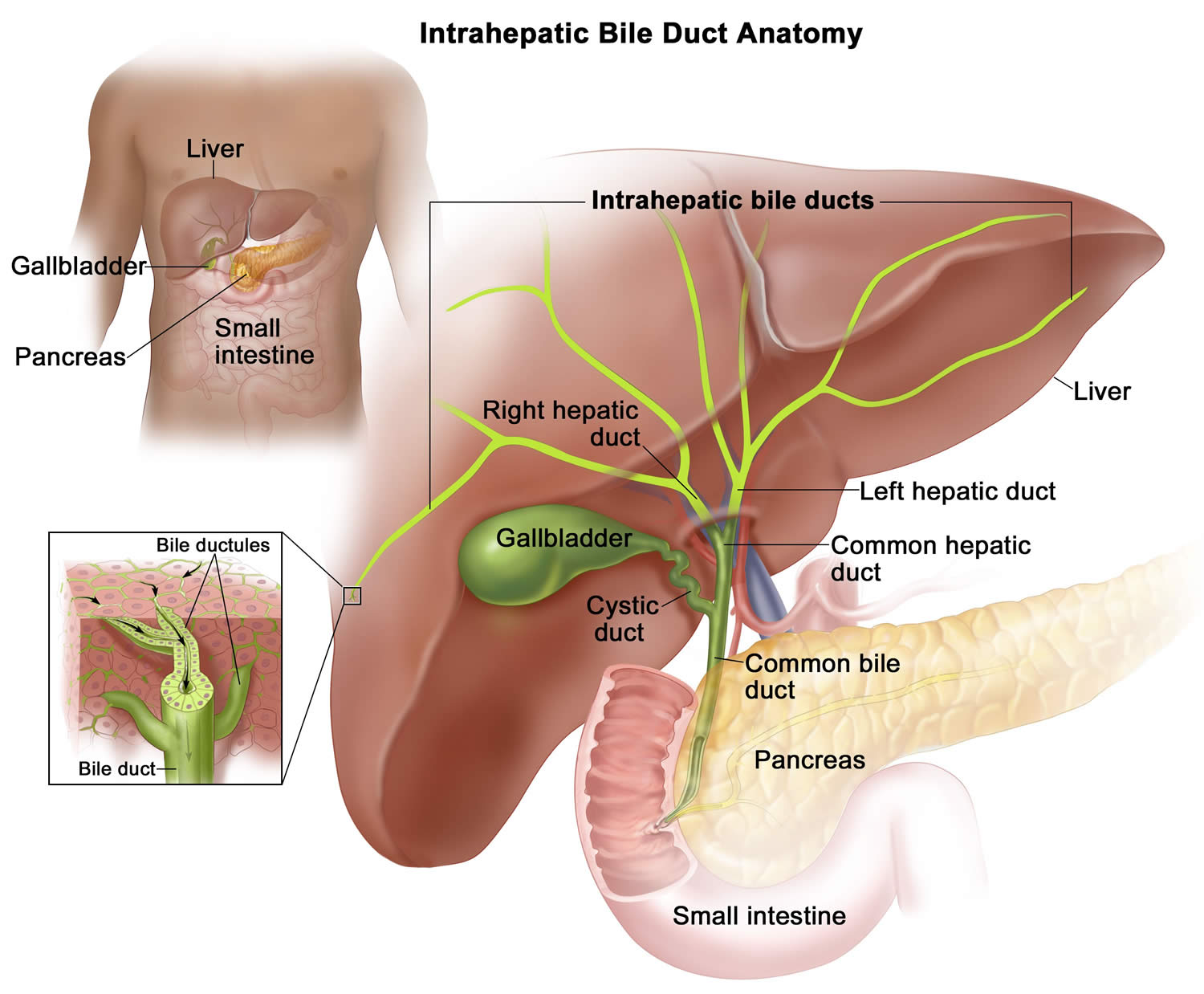

The bile ducts are a series of thin tubes that reach from the liver to the small intestine (see Figures 1 to 3). The major function of the bile ducts is to move a fluid called bile from the liver and gallbladder to the small intestine, where it helps digest the fats in food.

Different parts of the bile duct system have different names. In the liver it begins as many tiny tubes (called ductules) where bile collects from the liver cells. The ductules come together to form small ducts, which then merge into larger ducts and eventually the left and right hepatic ducts. All of these ducts within the liver are called intrahepatic bile ducts (Figure 2). Intrahepatic bile ducts are a network of small tubes that carry bile inside the liver. The smallest ducts, called ductules, come together to form the right and left hepatic ducts, which lead out of the liver. The two ducts join outside the liver and form the common hepatic duct. The cystic duct from the gallbladder joins the common hepatic duct to form the common bile duct. The common bile duct passes through the pancreas and ends in the small intestine. Bile is made by the liver and stored in the gallbladder. When food is being digested, bile is released from the gallbladder and flows through the common bile duct and pancreas into small intestine, where it helps digest fats.

The left and right hepatic ducts exit from the liver and join to form the common hepatic duct in an area called the hilum.

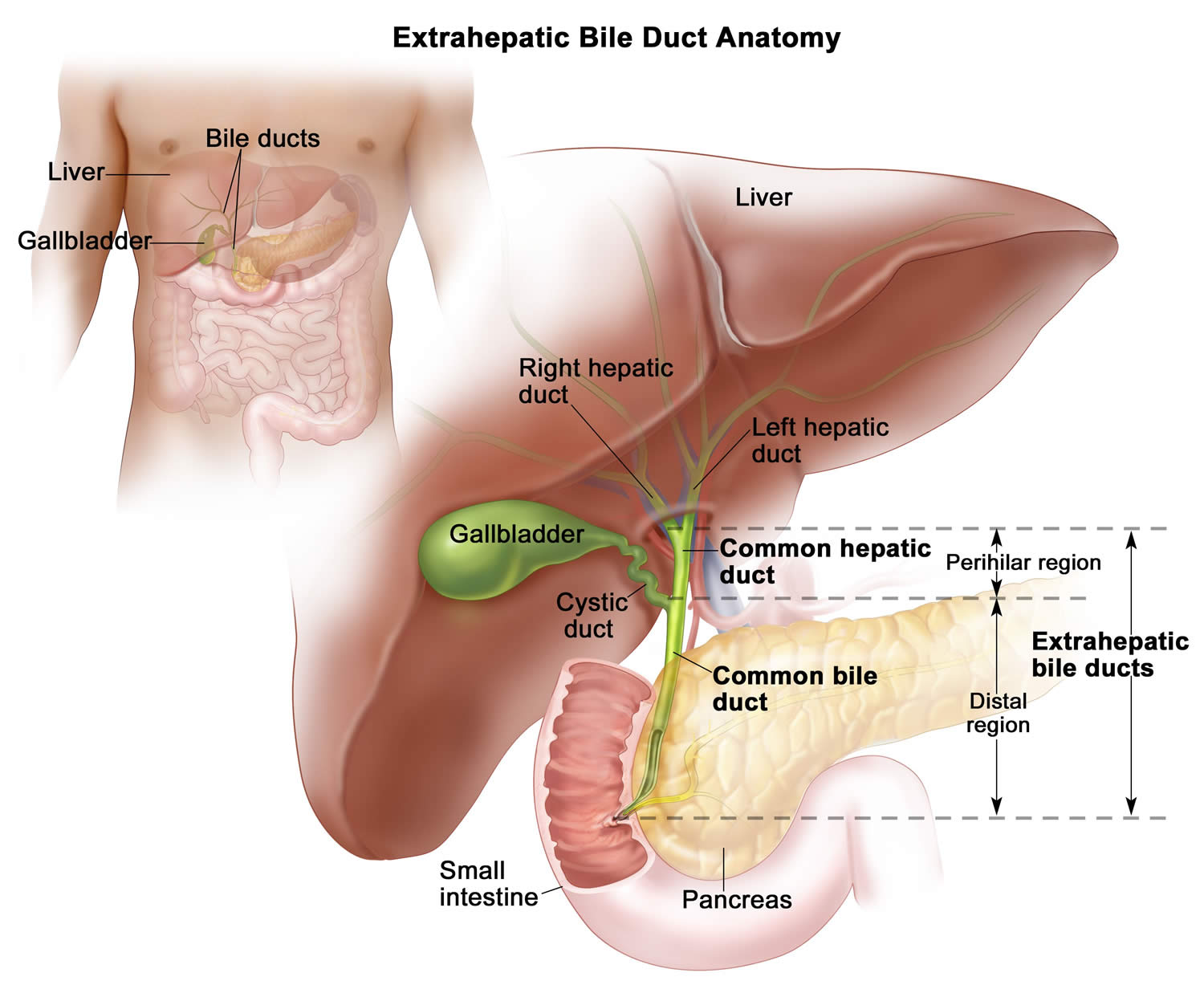

The bile ducts located outside of the liver are called extrahepatic bile ducts. They include part of the right and left hepatic ducts that are outside the liver, the common hepatic duct, and the common bile duct. The extrahepatic bile ducts can be further divided into the common hepatic duct (perihilar region) and the common bile duct (distal region) (Figure 3).

- Common hepatic duct (perihilar region). The hilum is the region where the right and left hepatic ducts exit the liver and join to form the common hepatic duct that is proximal to the origin of the cystic duct. Tumors of this region are also known as perihilar cholangiocarcinomas or Klatskin tumors.

- Common bile duct (distal region). This region includes the common bile duct and inserts into the small intestine. Tumors of this region are also known as extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (Figure 3).

Lower down, the gallbladder (a small organ that stores bile) joins the common hepatic duct through a small duct called the cystic duct. The combined duct is called the common bile duct. The common bile duct passes through part of the pancreas before it joins with the pancreatic duct and empties into the first part of the small intestine (the duodenum) at the ampulla of Vater (Figure 5).

Figure 1. Bile duct and gallbladder location

Figure 2. Intrahepatic bile ducts

Figure 3. Extrahepatic bile ducts

Figure 4. Bile duct anatomy

Figure 5. The common bile duct is closely associated with the pancreatic duct and the duodenum

Figure 5. The common bile duct is closely associated with the pancreatic duct and the duodenum Types of bile duct cancers by location

Types of bile duct cancers by location

Bile duct cancers can develop in any part of the bile duct system and, based on their location (see Figure 5 below), are classified into 3 types, they are named for where they grow in the bile ducts:

- Intrahepatic bile duct cancers (intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma): This type of cancer forms in the bile ducts inside the liver. Only a small number of bile duct cancers (cholangiocarcinoma) and accounts for only 10% of all cases.

- Extrahepatic bile duct cancer: This type of cancer forms in the bile ducts outside the liver. The two types of extrahepatic bile duct cancer are perihilar bile duct cancer and distal bile duct cancer:

- Perihilar bile duct cancer (hilar cholangiocarcinoma): This type of cancer is found in the area where the right and left bile ducts exit the liver and join to form the common hepatic duct. Perihilar bile duct cancer is also called a Klatskin tumor.

- Distal bile duct cancer (distal cholangiocarcinoma): This type of cancer is found in the area where the ducts from the liver and gallbladder join to form the common bile duct. The common bile duct passes through the pancreas and ends in the small intestine. Distal bile duct cancer is also called extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Sometimes, hilar cholangiocarcinoma and distal cholangiocarcinoma are grouped together and called extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Bile duct cancers in these different areas can cause different symptoms.

Figure 6. Cholangiocarcinoma type

Footnotes: Cholangiocarcinoma is classified as either intrahepatic or extrahepatic, with the second-order bile ducts acting as the separation point. Classically, extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma has been divided in perihilar and distal extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma at the level of the cystic duct.

[Source 3 ]Intrahepatic bile duct cancers

These cancers develop in the smaller bile duct branches inside the liver. They can sometimes be confused with cancers that start in the liver cells, which are called hepatocellular carcinomas, and are often treated the same way.

Perihilar (also called hilar) bile duct cancers

These cancers develop at the hilum, where the left and right hepatic ducts have joined and are just leaving the liver. These are also called Klatskin tumors. These cancers are grouped with distal bile duct cancers as extrahepatic bile duct cancers.

Distal bile duct cancers

These cancers are found further down the bile duct, closer to the small intestine. Like perihilar cancers, these are extrahepatic bile duct cancers because they start outside of the liver.

Types of bile duct cancer by cell type

Bile duct cancers can also be divided into types based on how the cancer cells look under the microscope. Nearly all bile duct cancers are called cholangiocarcinomas. Most of these are adenocarcinomas, which are cancers that start in glandular cells. Bile duct adenocarcinomas develop from the mucous gland cells that line the inside of the duct.

Other types of bile duct cancers are very rare and include 4:

- sarcomas,

- lymphomas,

- squamous cell carcinomas.

The information here does not cover these other types of bile duct cancer.

Figure 7. Liver and bile duct histology

Figure 8. Liver and bile duct histology (photomicrographs)

Bile duct cancer causes

Scientists don’t know the exact cause of most bile duct cancers, but researchers have found several risk factors that make a person more likely to develop bile duct cancer. There seems to be a link between bile duct cancer and things that irritate and inflame the bile ducts, whether it’s bile duct stones, infestation with a parasite, or something else.

Doctors are starting to understand how inflammation might lead to certain changes in the DNA of cells, making them grow abnormally and form cancers. DNA is the chemical in each of your cells that makes up your genes – the instructions for how your cells function. You usually look like your parents because they are the source of your DNA. But DNA affects more than how you look.

Some genes control when cells grow, divide into new cells, and die. Genes that help cells grow, divide, and stay alive are called oncogenes. Genes that slow down cell division or cause cells to die at the right time are called tumor suppressor genes. Cancers can be caused by DNA changes (mutations) that turn on oncogenes or turn off tumor suppressor genes. Changes in several different genes are usually needed for a cell to become cancerous.

Some people inherit DNA mutations from their parents that greatly increase their risk for certain cancers. But inherited gene mutations are not thought to cause very many bile duct cancers.

Gene mutations related to bile duct cancers are usually acquired during life rather than being inherited. For example, acquired changes in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene are found in most bile duct cancers. Other genes that may play a role in bile duct cancers include KRAS, HER2, and MET. Some of the gene changes that lead to bile duct cancer might be caused by inflammation. But sometimes what causes these changes is not known. Many gene changes might just be random events that sometimes happen inside a cell, without having an outside cause.

Risk Factors for Bile Duct Cancer

A risk factor is anything that affects your chance of getting a disease like cancer. There are several risk factors associated with bile duct cancer. Some risk factors, like smoking, can be changed. Others, like a person’s age or family history, can’t be changed.

But having a risk factor, or even several risk factors, does not mean that a person will get the disease. And many people who get the disease may have few or no known risk factors. People who think they may be at risk should discuss this with their doctor.

Researchers have found several risk factors that make a person more likely to develop bile duct cancer.

Certain diseases of the liver or bile ducts

People who have chronic (long-standing) inflammation of the bile ducts have an increased risk of developing bile duct cancer. Several conditions of the liver or bile ducts can cause this.

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a condition in which inflammation of the bile ducts (cholangitis) leads to the formation of scar tissue (sclerosis). People with this condition have an increased risk of bile duct cancer. The cause of the inflammation is not usually known. Many people with this disease also have inflammation of the large intestine called ulcerative colitis.

- Bile duct stones, which are similar to, but much smaller than gallstones, can also cause inflammation that increases the risk of bile duct cancer.

- Choledochal cysts are bile-filled sacs that are connected to the bile ducts. (Choledochal means having to do with the common bile duct.) The cells lining the sac often have areas of pre-cancerous changes, which increase a person’s risk for bile duct cancer.

- Liver fluke infections occur in some Asian countries when people eat raw or poorly cooked fish that are infected with these tiny parasite worms. In humans, these flukes live in the bile ducts and can cause bile duct cancer. There are several types of liver flukes. The ones most closely related to bile duct cancer risk are Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini 5, 6, 7. Currently, more than 600 million people are at risk of infection with these flukes (trematodes) 8. Opisthorchis viverrini is endemic in Southeast Asian countries, including Thailand, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Vietnam, and Cambodia 9 and Clonorchis sinensis infection is common in rural areas of Korea and China 7. Liver fluke infection is rare in the US, but it can affect people who travel to Asia.

- Abnormalities where the bile duct and pancreatic duct normally meet can allow digestive juices from the pancreas to reflux (flow back “upstream”) into the bile ducts. This backward flow also prevents the bile from being emptied through the bile ducts as quickly as normal. People with these abnormalities are at higher risk of bile duct cancer.

- Cirrhosis is damage to the liver from irritants such as alcohol and diseases such as hepatitis that cause scar tissue to form. Studies have found it raises the risk of bile duct cancer.

- Infection with hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus increases the risk of intrahepatic bile duct cancers. This may be at least in part due to the fact that long-term infections with these viruses can also lead to cirrhosis.

Other rare diseases of the liver and bile duct that may increase the risk of developing bile duct cancer include polycystic liver disease and Caroli syndrome (a dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts that is present at birth) 10, 11.

Inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease includes ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. People with these diseases have an increased risk of bile duct cancer. This is not explained completely by the link between ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Older age

Older people are more likely than younger people to get bile duct cancer. Most people diagnosed with bile duct cancer are in their 60s or 70s.

Ethnicity and geography

In the United States, the risk of bile duct cancer is highest among Hispanic Americans and Native Americans. Worldwide, bile duct cancer is much more common in Southeast Asia and China, largely because of the high rate of infection with liver flukes in these areas.

Obesity

Being overweight or obese can increase the risk of cancers of the gallbladder and bile ducts. This could be because obesity increases the risk of gallstones and bile duct stones. But there may be other ways that being overweight can lead to bile duct cancers, such as changes in certain hormones.

Exposure to Thorotrast

A radioactive substance called Thorotrast (thorium dioxide) was used as a contrast agent for x-rays until the 1950s. It was found to increase the risk for bile duct cancer, as well as some types of liver cancer, which is why it is no longer used.

Family history

A history of bile duct cancer in the family seems to increase a person’s chances of developing this cancer, but the risk is still low because this is a rare disease. Most bile duct cancers are not found in people with a family history of the disease.

Diabetes

People with diabetes (type 1 or type 2) have a higher risk of bile duct cancer. This increase in risk is not high, and the overall risk of bile duct cancer in someone with diabetes is still low.

Alcohol

People who drink alcohol are more likely to get intrahepatic bile duct cancer. The risk is higher in those who have liver problems from drinking alcohol.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the build-up of extra fat in the liver cells that’s not caused by alcohol. Over time, this can cause swelling and scarring that can progress to cancer.

Other possible risk factors

Studies have found several other factors that might increase the risk of bile duct cancer, but the links are not as clear. These include:

- Smoking

- Pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas)

- Infection with HIV (the virus that causes AIDS)

- Exposure to asbestos

- Exposure to radon or other radioactive chemicals

- Exposure to dioxin, nitrosamines, or polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)

Can Bile Duct Cancer Be Prevented?

There is no known way to prevent most bile duct cancers in the United States. Many of the known risk factors for bile duct cancer, such as age, ethnicity, and bile duct abnormalities, are beyond our control. But there are things you can do that might lower your risk.

Getting to and staying at a healthy weight is one important way a person may reduce their risk of bile duct cancer, as well as many other types of cancer. The American Cancer Society recommends that people try to stay at a healthy weight, keep physically active, and follow a healthy eating pattern that includes plenty of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and that limits or avoids red and processed meats, sugary drinks, and highly processed foods.

Other ways that people may be able to reduce their risk of bile duct cancer include:

- Get vaccinated against the hepatitis B virus (HBV) to prevent infection with this virus and the cirrhosis it can cause.

- Take precautions to avoid blood-borne or sexually transmitted infections by HBV and other viruses (like hepatitis C virus) to help prevent cirrhosis.

- Treat hepatitis infections (such as B and C) to help prevent cirrhosis.

- Avoid excessive alcohol use to help prevent cirrhosis.

- Quit (or don’t start) smoking.

- Avoid exposure to certain chemicals (e.g. dioxin, nitrosamines, or polychlorinated biphenyls).

Bile duct cancer signs and symptoms

Bile duct cancer does not usually cause signs or symptoms until later in the course of the disease, but sometimes symptoms can appear sooner and lead to an early diagnosis. If the cancer is diagnosed at an early stage, treatment might be more effective.

When bile duct cancer does cause symptoms, it is usually because a bile duct is blocked.

Jaundice

Jaundice is yellowing of the skin and eyes. Normally, bile is made by the liver and released into the intestine. Jaundice occurs when the liver can’t get rid of bile, which contains a greenish-yellow chemical called bilirubin. As a result, bilirubin backs up into the bloodstream and settles in different parts of the body. This can often be seen in the skin and the white part of the eyes.

Jaundice is the most common symptom of bile duct cancer, but most cases of jaundice are not caused by cancer. Jaundice is more often caused by hepatitis (inflammation of the liver) or a gallstone that has traveled to the bile duct. But whenever jaundice occurs, a doctor should be seen right away.

Itching

Excess bilirubin in the skin can also cause itching. Most people with bile duct cancer notice itching.

Light-colored/greasy stools

Bilirubin contributes to the brown color of bowel movements, so if it doesn’t reach the intestines, the color of a person’s stool might be lighter.

If the cancer blocks the release of bile and pancreatic juices into the intestine, a person might not be able to digest fatty foods. The undigested fat can also cause stools to be unusually pale. They might also be bulky, greasy, and float in the toilet.

Dark urine

When bilirubin levels in the blood get high, it can also come out in the urine and turn it dark.

Abdominal (belly) pain

Early bile duct cancers usually do not cause pain, but more advanced cancers may cause abdominal pain, especially below the ribs on the right side.

Loss of appetite/weight loss

People with bile duct cancer may not feel hungry and may lose weight (without dieting).

Fever

Some people with bile duct cancer develop fevers 38 °C (100.4 °F) or above.

Nausea and vomiting

These are not common symptoms of bile duct cancer, but they may occur in people who develop an infection (cholangitis) as a result of bile duct blockage. They are often seen along with a fever.

Bile duct cancer is not common, and these symptoms and signs are more likely to be caused by something other than bile duct cancer. For example, people with gallstones may have many of these same symptoms. There are many far more common causes of abdominal pain than bile duct cancer. And hepatitis (an inflamed liver most often caused by infection with a virus) is a much more common cause of jaundice. Still, if you have any of these problems, it’s important to see your doctor right away so the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

Bile duct cancer diagnosis

Most bile duct cancers are not found until patients go to a doctor because they have symptoms. The doctor will need to take a history and do a physical exam, and then might order some tests.

If your doctor confirms a diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma, he or she tries to determine the extent (stage) of the cancer. Often this involves additional imaging tests. Your cancer’s stage helps determine your prognosis and your treatment options.

History and physical exam

If there is reason to suspect that you might have bile duct cancer, your doctor will want to take a complete medical history to check for risk factors and to learn more about your symptoms.

A physical exam is done to look for signs of bile duct cancer or other health problems. If bile duct cancer is suspected, the exam will focus mostly on the abdomen to check for any lumps, tenderness, or buildup of fluid. The skin and the white part of the eyes will be checked for jaundice (a yellowish color).

If symptoms and/or the results of the physical exam suggest you might have bile duct cancer, other tests will be done. These could include lab tests, imaging tests, and other procedures.

Blood tests

If your doctor suspects cholangiocarcinoma, he or she may have you undergo one or more of the following tests:

Liver function tests and gallbladder function

The doctor may order lab tests to find out how much bilirubin is in the blood. Bilirubin is the chemical that causes jaundice. Problems in the bile ducts, gallbladder, or liver can raise the blood level of bilirubin. A high bilirubin level tells the doctor that there may be problems with the bile duct, gallbladder, or liver.

Along with tests for bilirubin, the doctor may also order tests for albumin, for liver enzymes (alkaline phosphatase, AST, ALT, and GGT), and certain other substances in your blood. These are sometimes called liver function tests. They can indicate bile duct, gallbladder, or liver disease. If levels of these substances are higher, it might point to blockage of the bile duct, but they can’t show if it is due to cancer or some other reason.

Tumor markers test

Tumor markers are substances made by cancer cells that can sometimes be found in the blood. People with bile duct cancer may have high blood levels of the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) tumor markers. High amounts of these substances often mean that cancer is present, but the high levels can also be caused by other types of cancer, or even by problems other than cancer, such as bile duct inflammation and obstruction. Also, not all bile duct cancers make these tumor markers, so low or normal levels do not always mean cancer is not present.

These tests can sometimes be useful after a person is diagnosed with bile duct cancer. If the levels of these markers are found to be high, they can be followed over time to help tell how well treatment is working.

Imaging tests

Imaging tests use x-rays, magnetic fields, or sound waves to create pictures of the inside of your body. Imaging tests can be done for a number of reasons, including:

- To help find suspicious areas that might be cancer

- To help a doctor guide a biopsy needle into a suspicious area to take a sample

- To learn how far cancer has spread

- To help find out if treatment is working

- To look for signs of the cancer coming back after treatment

Imaging tests can often show a bile duct blockage. But they often can’t show if the blockage is caused by a tumor or a benign problem such as scarring.

People who have (or might have) bile duct cancer may have one or more of the following tests.

Ultrasound

For this test, a small, microphone-like instrument called a transducer gives off sound waves and picks up their echoes as they bounce off organs inside the body. The echoes are converted by a computer into an image on a screen. The echo patterns can help find tumors and show how far they have grown into nearby areas. They can also help tell whether some tumors are benign or malignant.

- Abdominal ultrasound: This is often the first imaging test done in people who have symptoms such as jaundice or pain in the right upper part of their abdomen. This is an easy test to have and does not use radiation. You simply lie on a table while the doctor or ultrasound technician moves the transducer along the skin over the right upper part of the abdomen. Usually, the skin is first lubricated with gel. This type of ultrasound can also be used to guide a needle into a suspicious area or lymph node so that cells can be removed (biopsied) and looked at under a microscope. This is known as an ultrasound-guided needle biopsy.

- Endoscopic or laparoscopic ultrasound: In these techniques, the doctor puts the ultrasound transducer inside the body and closer to the bile duct, which gives more detailed images than a standard ultrasound. The transducer is on the end of a thin, lighted tube that has an attached viewing device. The tube is either passed through the mouth, down through the stomach, and into the small intestine near the bile ducts (endoscopic ultrasound) or through a small surgical cut in the side of the patient’s body (laparoscopic ultrasound). If there is a tumor, the doctor might be able to see how far it has grown and spread, which can help in planning for surgery. Ultrasound may be able to show if nearby lymph nodes are enlarged, which can be a sign that cancer has reached them. Needle biopsies of suspicious areas might be taken as well.

Computed tomography (CT) scan

The CT scan uses x-rays to make detailed cross-sectional images of your body. Instead of taking one x-ray, a CT scanner takes many pictures as it rotates around you. A computer then combines these into images of slices of the part of your body that is being studied.

CT scans can have several uses:

- They often help diagnose bile duct cancer by showing tumors in the area.

- They can help stage the cancer (find out how far it has spread). CT scans can show the organs near the bile duct (especially the liver), as well as lymph nodes and distant organs where cancer might have spread to.

- A type of CT known as CT angiography can be used to look at the blood vessels around the bile ducts. This can help determine if surgery is a treatment option.

- CT scans can also be used to guide a biopsy needle into a suspected tumor or metastasis. For this procedure, called a CT-guided needle biopsy, the patient remains on the CT scanning table, while the doctor advances a biopsy needle through the skin and toward the mass. CT scans are repeated until the needle is within the mass. A biopsy sample is then removed and looked at under a microscope.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

Like CT scans, MRI scans provide detailed images of soft tissues in the body. But MRI scans use radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays. A contrast material called gadolinium may be injected into a vein before the scan to better see details.

MRI scans provide a great deal of detail and can be very helpful in looking at the bile ducts and nearby organs. Sometimes they can help tell a benign tumor from a cancerous one.

Special types of MRI scans may also be used in people who may have bile duct cancer:

- MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) can be used to look at the bile ducts and is described in the section on cholangiography.

- MR angiography (MRA) looks at blood vessels and is mentioned in the section on angiography.

Cholangiography

A cholangiogram is an imaging test that looks at the bile ducts to see if they are blocked, narrowed, or dilated (widened). This can help show if someone might have a tumor that is blocking a duct. It can also be used to help plan surgery. There are several types of cholangiograms, which have different pros and cons.

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP): This is a non-invasive way to image the bile ducts using the same type of machine used for standard MRI scans. It does not require an endoscope or an IV infusion of a contrast agent, unlike the other types of cholangiograms. Because it is non-invasive, doctors often use MRCP if the purpose of the test is just to image the bile ducts. But this test can’t be used to get biopsy samples of tumors or to place stents (small tubes) in the ducts to keep them open.

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): In this procedure, a doctor passes a long, flexible tube (endoscope) down the throat, through the esophagus and stomach, and into the first part of the small intestine. This is usually done while you are sedated (given medicine to make you sleepy). A small catheter (tube) is passed from the end of the endoscope and into the common bile duct. A small amount of contrast dye is injected through the tube to help outline the bile ducts and pancreatic duct as x-rays are taken. The images can show narrowing or blockage of these ducts. This test is more invasive than MRCP, but it has the advantage of allowing the doctor to take samples of cells or fluid to be looked at under a microscope. ERCP can also be used to place a stent (a small tube) into a duct to help keep it open.

- Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC): In this procedure, the doctor places a thin, hollow needle through the skin of the belly and into a bile duct within the liver. You will get medicine through an IV line to make you sleepy before the test. A local anesthetic is also used to numb the area before inserting the needle. A contrast dye is then injected through the needle, and x-rays are taken as it passes through the bile ducts. Like ERCP, this approach can also be used to take samples of fluid or tissues or to place stents (small tubes) in the bile duct to help keep it open. Because it is more invasive (and might cause more pain), PTC is not usually used unless ERCP has already been tried or can’t be done for some reason.

Angiography

Angiography is an x-ray procedure for looking at blood vessels. For this test, a small amount of contrast dye is injected into an artery to outline blood vessels before x-ray images are taken. The images show if blood flow in an area is blocked or affected by a tumor, and any abnormal blood vessels in the area. The test can also show if a bile duct cancer has grown through the walls of certain blood vessels. This information is mainly used to help surgeons decide whether a cancer can be removed and to help plan the operation.

X-ray angiography can be uncomfortable because the doctor has to put a small catheter (a flexible hollow tube) into the artery leading to the bile ducts to inject the dye. Usually the catheter is put into an artery in your inner thigh and threaded up into the artery supplying the bile ducts. A local anesthetic is often used to numb the area before inserting the catheter. Then the dye is injected quickly to outline all the vessels while the x-rays are being taken.

Angiography can also be done with a CT scanner (CT angiography) or an MRI scanner (MR angiography). These techniques are now used more often because they give information about the blood vessels without the need for a catheter. You may still need an IV line so that a contrast dye can be injected into the bloodstream during the imaging.

Other tests

Doctors may also place special instruments (endoscopes) into the body to get a more direct look at the bile duct and surrounding areas. The scopes may be passed through small surgical incisions or through natural body openings like the mouth.

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is a type of minor surgery. The doctor inserts a thin tube with a light and a small video camera on the end (a laparoscope) through a small cut in the front of the abdomen to look at the bile duct, gallbladder, liver, and other organs and tissues in the area. (Sometimes more than one cut is made.) This procedure is typically done in the operating room while you are under general anesthesia (in a deep sleep).

Laparoscopy can help doctors plan surgery or other treatments, and can help assess the stage (extent) of the cancer. If needed, doctors can also insert instruments through the incisions to remove small biopsy samples to be looked at under a microscope. This procedure is often done before surgery to remove the cancer, to help make sure the tumor can be removed completely.

Cholangioscopy

This procedure can be done during an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (see above). The doctor passes a very thin fiber-optic tube with a tiny camera on the end down through the larger tube used for the ERCP. From there it can be maneuvered into the bile ducts. This lets the doctor see any blockages, stones, or tumors and even biopsy them.

Biopsy

Imaging tests (ultrasound, CT or MRI scans, cholangiography, etc.) might suggest that a bile duct cancer is present, but in many cases a sample of bile duct cells or tissue is removed (biopsied) and looked at under a microscope to be sure of the diagnosis.

But a biopsy may not always be done before surgery for a possible bile duct cancer. If imaging tests suggest there is a tumor in the bile duct, the doctor may decide to proceed directly to surgery and to treat it as a bile duct cancer.

How your doctor collects a biopsy sample may influence which treatment options are available to you later. For example, if your bile duct cancer is biopsied by fine-needle aspiration, you will become ineligible for liver transplantation. Don’t hesitate to ask about your doctor’s experience with diagnosing cholangiocarcinoma. If you have any doubts, get a second opinion.

Types of biopsies

There are several ways to take biopsy samples to diagnose bile duct cancer. How your doctor collects a biopsy sample may influence which treatment options are available to you later. For example, if your bile duct cancer is biopsied by fine-needle aspiration, you will become ineligible for liver transplantation. Don’t hesitate to ask about your doctor’s experience with diagnosing cholangiocarcinoma. If you have any doubts, get a second opinion.

During cholangiography: If endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) is being done, a sample of bile may be collected during the procedure to look for tumor cells within the fluid.

Bile duct cells and tiny fragments of bile duct tissue can also be sampled by biliary brushing. Instead of injecting contrast dye and taking x-ray pictures (as for ERCP or PTC), the doctor advances a small brush with a long, flexible handle through the endoscope or needle. The end of the brush is used to scrape cells and small tissue fragments from the lining of the bile duct, which are then looked at under a microscope.

During cholangioscopy: Biopsy specimens can also be taken during cholangioscopy. This lets the doctor see the inside surface of the bile duct and take samples of suspicious areas.

Needle biopsy: For this test, a thin, hollow needle is inserted through the skin and into the tumor without first making a surgical incision. (The skin is numbed first with a local anesthetic.) The needle is usually guided into place using ultrasound or CT scans. When the images show that the needle is in the tumor, a sample is drawn into the needle and sent to the lab to be viewed under a microscope.

In most cases, this is done as a fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy, which uses a very thin needle attached to a syringe to suck out (aspirate) a sample of cells. Sometimes, the FNA doesn’t provide enough cells for a definite diagnosis, so a core needle biopsy may be done, which uses a slightly larger needle to get a bigger sample.

Lab tests of biopsy samples

Along with looking at the biopsy samples with a microscope to see if they contain cancer cells, other lab tests might be done on the samples as well.

For example, cancer cells in the biopsy samples (or surgery samples) might be tested for certain gene or protein changes (sometimes called biomarkers), such as changes in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) and IDH1 genes. This can help determine if certain targeted drugs might be helpful in treating the cancer.

Bile Duct Cancer Stages

The stage of a cancer describes how much cancer is in the body. It helps determine how serious the cancer is and how best to treat it. Doctors also use a cancer’s stage when talking about survival statistics.

The stage is determined by the results of the physical exam, imaging and other tests, and by the results of surgery if it has been done.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system

A staging system is a standard way for the cancer care team to sum up the extent of a cancer. The main system used to describe the stages of bile duct cancer is the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system. There are actually 3 different staging systems for bile duct cancers, depending on where they start:

- Intrahepatic bile duct cancers (those starting within the liver)

- Perihilar (hilar) bile duct cancers (those starting in the hilum, the area just outside the liver)

- Distal bile duct cancers (those starting farther down the bile duct system)

No matter where they are, nearly all bile duct cancers start in the innermost layer of the wall of the bile duct (called the mucosa). Over time they can grow through the wall toward the outside of the bile duct. If a tumor grows through the bile duct wall, it can invade (grow into) nearby blood vessels, organs, or other structures. It might also enter the nearby lymphatic or blood vessels, from which it can spread to nearby lymph nodes or to other parts of the body.

The TNM system for all bile duct cancers is based on 3 key pieces of information:

- T describes whether the main (primary) tumor has invaded through the wall of the bile duct and whether it has invaded other nearby organs or tissues.

- N describes whether the cancer spread to nearby (regional) lymph nodes (bean-sized collections of immune system cells throughout the body).

- M indicates whether the cancer has metastasized (spread) to other organs of the body. (The most common sites of bile duct cancer spread are the liver, peritoneum [the lining of the abdominal cavity], and the lungs.)

Intrahepatic Bile Duct Cancers Staging

After someone is diagnosed with intrahepatic bile duct cancer, doctors will try to figure out if it has spread, and if so, how far. This process is called staging. The stage of a cancer describes how much cancer is in the body. It helps determine how serious the cancer is and how best to treat it. Doctors also use a cancer’s stage when talking about survival statistics.

The earliest stage intrahepatic bile duct cancers are stage 0 (also called carcinoma in situ, or CIS), and then range from stages I (1) through IV (4). As a rule, the lower the number, the less the cancer has spread. A higher number, such as stage IV, means cancer has spread more. And within a stage, an earlier letter means a lower stage. Although each person’s cancer experience is unique, cancers with similar stages tend to have a similar outlook and are often treated in much the same way.

How is the stage determined?

The staging system most often used for intrahepatic bile duct cancer is the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system, which is based on 3 key pieces of information:

- The extent (size) of the main tumor (T): How large has the cancer grown? Has the cancer reached nearby structures or organs?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes?

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant lymph nodes or distant organs such as the bones, lungs, or peritoneum (the lining of the abdomen)?

The system described below is the most recent American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system, effective January 2018. It is used only for intrahepatic bile duct cancers (those starting within the liver).

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced.

Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage.

Intrahepatic bile duct cancer is typically given a clinical stage based on the results of a physical exam, biopsy, and imaging tests.

If surgery is done, the pathologic stage (also called the surgical stage) is determined by examining tissue removed during the operation.

Cancer staging can be complex, so ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

Table 1. Stages of Intrahepatic bile duct cancer

| AJCC Stage | Stage grouping | Stage description* |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis N0 M0 | In stage 0 intrahepatic bile duct cancer, abnormal cells are found in the innermost layer of tissue lining the intrahepatic bile duct called the mucosa. It hasn’t started growing into the deeper layers (Tis). Stage 0 is also called carcinoma in situ. It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 1A | T1a N0 M0 | The tumor is no more than 5 cm (about 2 inches) across and has not invaded nearby blood vessels (T1a). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 1B | T1b N0 M0 | The tumor is more than 5 cm (about 2 inches) across but has not invaded nearby blood vessels (T1b). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 2 | T2 N0 M0 | The tumor has grown into nearby blood vessels, OR there are 2 or more tumors, which may or may not have grown into nearby blood vessels (T2). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 3A | T3 N0 M0 | The cancer has grown through the visceral peritoneum (the outer lining of organs in the abdomen) (T3). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 3B | T4 N0 M0 | The cancer has grown directly into nearby structures outside of the liver (T4). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| OR | ||

| Any T N1 M0 | The cancer is any size and might or might not be growing outside the bile duct (Any T) and has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N1). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). | |

| 4 | Any T Any N M1 | The cancer is any size and may or may not be growing outside the bile duct (Any T). It may or may not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (Any N). It has spread to distant organs such as the bones or lungs (M1). |

Footnotes:

*The T categories are described in the table above, except for:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

The N categories are described in the table above, except for:

- NX: Nearby lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Perihilar Bile Duct Cancers Staging

The earliest stage perihilar bile duct cancers are stage 0, also called carcinoma in situ (CIS) or high-grade biliary intraepithelial neoplasia, and then range from stages I (1) through IV (4). As a rule, the lower the number, the less the cancer has spread. A higher number, such as stage IV, means cancer has spread more. And within a stage, an earlier letter means a lower stage. Although each person’s cancer experience is unique, cancers with similar stages tend to have a similar outlook and are often treated in much the same way.

The system described below is the most recent AJCC system, effective January 2018. It is used only for perihilar bile duct cancers.

Perihilar bile duct cancer is typically given a clinical stage based on the results of a physical exam, biopsy, and imaging tests. If surgery is done, the pathologic stage (also called the surgical stage) is determined by examining tissue removed during the operation.

Cancer staging can be complex, so ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

Table 2. Stages of Perihilar bile duct cancer

| AJCC Stage | Stage grouping | Stage description* |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis N0 M0 | The cancer is only in the mucosa (the innermost layer of cells in the bile duct). It hasn’t started growing into the deeper layers (Tis). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 1 | T1 N0 M0 | The cancer has grown into deeper layers of the bile duct wall, such as the muscle layer or fibrous tissue layer (T1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 2 | T2a or T2b N0 M0 | The tumor has grown through the bile duct wall and into the nearby fatty tissue (T2a) or into the nearby liver tissue (T2b). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 3A | T3 N0 M0 | The cancer is growing into branches of the main blood vessels of the liver (the portal vein and/or the hepatic artery) on one side (left or right) (T3). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 3B | T4 N0 M0 | The cancer is growing into the main blood vessels of the liver (the portal vein and/or the common hepatic artery) or into branches of these vessels on both sides (left and right), OR the cancer is growing into other bile ducts on one side (left or right) and a main blood vessel on the other side (T4). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 3C | Any T N1 M0 | The cancer is any size and may or may not be growing outside the bile duct or into nearby blood vessels (Any T) and has spread to 1 to 3 nearby lymph nodes (N1). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| 4A | Any T N2 M0 | The cancer is any size and may or may not be growing outside the bile duct or into nearby blood vessels (Any T). It has also spread to 4 or more nearby lymph nodes (N2). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| 4B | Any T Any N M1 | The cancer is any size and may or may not be growing outside the bile duct or into nearby blood vessels (Any T). It may or may not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (Any N). It has spread to distant organs such as the bones, lungs, or distant parts of the liver (M1). |

Footnotes:

*The T categories are described in the table above, except for:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

The N categories are described in the table above, except for:

- NX: Nearby lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Distal Bile Duct Cancers Staging

The earliest stage distal bile duct cancers are stage 0, also called carcinoma in situ (CIS) or high-grade biliary intraepithelial neoplasia, and then range from stages I (1) through IV (4). As a rule, the lower the number, the less the cancer has spread. A higher number, such as stage IV, means cancer has spread more. And within a stage, an earlier letter means a lower stage. Although each person’s cancer experience is unique, cancers with similar stages tend to have a similar outlook and are often treated in much the same way.

The system described below is the most recent AJCC system, effective January 2018. It is used only for distal bile duct cancers.

Distal bile duct cancer is typically given a clinical stage based on the results of a physical exam, biopsy, and imaging tests (as described in How Is Bile Duct Cancer Diagnosed?). If surgery is done, the pathologic stage (also called the surgical stage) is determined by examining tissue removed during the operation.

Cancer staging can be complex, so ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

Table 3. Stages of Distal bile duct cancer

| AJCC Stage | Stage grouping | Stage description* |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis N0 M0 | The cancer is only in the mucosa (the innermost layer of cells in the bile duct). It hasn’t started growing into the deeper layers (Tis). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 1 | T1 N0 M0 | The cancer has grown less than 5 mm (about 1/5 of an inch) into the bile duct wall (T1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 2A | T2 N0 M0 | The cancer has grown between 5 mm (about 1/5 of an inch) and 12 mm (about ½ inch) into the bile duct wall (T2). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| OR | ||

| T1 N1 M0 | The cancer has grown less than 5 mm (about 1/5 of an inch) into the bile duct wall (T1) and has spread to 1 to 3 nearby lymph nodes (N1). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). | |

| 2B | T3 N0 M0 | The cancer has grown more than 12 mm (about ½ inch) into the bile duct wall (T3). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| OR | ||

| T2 or T3 N1 M0 | The cancer has grown 5 mm (about 1/5 of an inch) or more into the bile duct wall (T2 or T3) and has spread to 1 to 3 nearby lymph nodes (N1). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). | |

| 3A | T1, T2, or T3 N2 M0 | The cancer has grown to any depth into the bile duct wall (T1, T2, or T3) and to 4 or more nearby lymph nodes (N2). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| 3B | T4 Any N M0 | The cancer is growing into nearby blood vessels (the celiac artery or its branches, the superior mesenteric artery, and/or the common hepatic artery) (T4). The cancer may or may not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (Any N). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| 4 | Any T Any N M1 | The cancer has grown to any depth within the bile duct wall and may or may not be growing into nearby blood vessels (Any T). It may or may not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (any N). It has spread to distant organs such as the liver, lungs, or peritoneum (inner lining of the abdomen [belly]) (M1). |

Footnotes:

*The T categories are described in the table above, except for:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

The N categories are described in the table above, except for:

- NX: Nearby lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Resectable Versus Unresectable Bile Duct Cancers

The TNM staging system provides a detailed summary of how far the cancer has spread and gives doctors an idea about a person’s prognosis (outlook). But for treatment purposes, doctors often use a simpler system based on whether or not the cancer can likely be removed (resected) with surgery:

- Resectable cancers are those that doctors believe can be removed completely by surgery.

- Unresectable cancers have spread too far or are in too difficult a place to be removed entirely by surgery.

In general terms, most stage 0, 1, and 2 cancers and possibly some stage 3 cancers are resectable, while most stage 3 and 4 tumors are unresectable. But this also depends on other factors, such as the size and location of the cancer and whether a person is healthy enough for surgery.

Cholangiocarcinoma prognosis

Prognosis depends in part on the tumor’s anatomic location, which affects resectability. Because of proximity to major blood vessels and diffuse extension within the liver, a bile duct tumor can be difficult to resect. Total resection is possible in 25% to 30% of lesions that originate in the distal bile duct; the resectability rate is lower for lesions that occur in more proximal sites 15.

Complete resection with negative surgical margins offers the only chance of cure for bile duct cancer. For localized, resectable extrahepatic and intrahepatic tumors, the presence of involved lymph nodes and perineural invasion are significant adverse prognostic factors 16, 17.

Additionally, the following have been associated with worse outcomes among patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas 18, 19.:

- A personal history of primary sclerosing cholangitis.

- Elevated cancer antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) level.

- Periductal infiltrating tumor growth pattern.

- Presence of hepatic venous invasion.

Cholangiocarcinoma – bile duct cancer survival rate

When discussing cancer survival statistics, doctors often use a number called the 5-year survival rate. The 5-year survival rate refers to the percentage of patients who live at least 5 years after their cancer is diagnosed. Of course, some of these people live much longer than 5 years.

Five-year relative survival rates, such as the numbers below, assume that some people will die of other causes and compare the observed survival with that expected for people without the cancer. This is a better way to see the impact of the cancer on survival.

To get 5-year survival rates, doctors have to look at people who were treated at least 5 years ago. Improvements in treatment since then may result in a better outlook for people now being diagnosed with bile duct cancer.

There are some important points to note about the bile duct cancer survival rates below:

These statistics come from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program and are based on people diagnosed with bile duct cancer in the years 2011 to 2017. SEER does not separate these cancers by AJCC stage, but instead puts them into 3 groups: localized, regional, and distant. Localized is like AJCC stage 1. Regional includes stages 2 and 3. Distant means the same as stage 4.

- Localized: There is no sign that the cancer has spread outside of the bile ducts.

- Regional: The cancer has spread outside the bile ducts to nearby structures or lymph nodes.

- Distant: The cancer has spread to distant parts of the body, such as the lungs.

Survival rates are often based on previous outcomes of large numbers of people who had the disease, but they can’t predict what will happen with any particular person. Many other factors can also affect a person’s outlook, such as their age and overall health, and how well the cancer responds to treatment. Even when taking these other factors into account, survival rates are at best rough estimates. Your doctor can tell you how the numbers above apply to you, as he or she knows your situation best.

SEER also does not separate perihilar bile duct cancers from distal bile duct cancers. Instead, these are grouped together as extrahepatic bile duct cancers.

Table 4. Intrahepatic bile duct cancer survival rate

| Stage | 5-year relative survival |

|---|---|

| Localized | 24% |

| Regional | 9% |

| Distant | 2% |

Footnotes:

- These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

- These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread. But other factors, such as your age and overall health, and how well the cancer responds to treatment, can also affect your outlook.

- People now being diagnosed with bile duct cancer may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments improve over time, and these numbers are based on people who were diagnosed and treated at least five years earlier.

Table 5. Extrahepatic bile duct cancer survival rate

| Stage | 5-year relative survival |

|---|---|

| Localized | 17% |

| Regional | 16% |

| Distant | 2% |

Footnotes:

- These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

- These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread. But other factors, such as your age and overall health, and how well the cancer responds to treatment, can also affect your outlook.

- People now being diagnosed with bile duct cancer may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments improve over time, and these numbers are based on people who were diagnosed and treated at least five years earlier.

Cholangiocarcinoma treatment

After bile duct cancer is found and staged, your cancer care team will discuss your treatment options with you. It is important for you to take time and think about your choices. In choosing a treatment plan, there are some factors to consider:

- The location and extent of the cancer

- Whether the cancer is resectable (removable by surgery)

- The likely side effects of treatment

- Your overall health

- The chances of curing the disease, extending life, or relieving symptoms

The main types of treatment for bile duct cancer include:

- Surgery. When possible, doctors try to remove as much of the cancer as they can. For very small bile duct cancers, this involves removing part of the bile duct and joining the cut ends. For more-advanced bile duct cancers, nearby liver tissue, pancreas tissue or lymph nodes may be removed as well.

- Liver transplant. Surgery to remove your liver and replace it with one from a donor (liver transplant) may be an option in certain cases for people with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. For many, a liver transplant is a cure for hilar cholangiocarcinoma, but there is a risk that the cancer will recur after a liver transplant.

- Chemotherapy. Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy may be used before a liver transplant. It may also be an option for people with advanced cholangiocarcinoma to help slow the disease and relieve signs and symptoms.

- Radiation therapy. Radiation therapy uses high-energy sources, such as photons (x-rays) and protons, to damage or destroy cancer cells. Radiation therapy can involve a machine that directs radiation beams at your body (external beam radiation). Or it can involve placing radioactive material inside your body near the site of your cancer (brachytherapy).

- Photodynamic therapy. In photodynamic therapy, a light-sensitive chemical is injected into a vein and accumulates in the fast-growing cancer cells. Laser light directed at the cancer causes a chemical reaction in the cancer cells, killing them. You’ll typically need multiple treatments. Photodynamic therapy can help relieve your signs and symptoms, and it may also slow cancer growth. You’ll need to avoid sun exposure after treatments.

- Targeted drug therapy. Targeted drug treatments focus on specific abnormalities present within cancer cells. By blocking these abnormalities, targeted drug treatments can cause cancer cells to die. Your doctor may test your cancer cells to see if targeted therapy may be effective against your cholangiocarcinoma.

- Immunotherapy. Immunotherapy uses your immune system to fight cancer. Your body’s disease-fighting immune system may not attack your cancer because the cancer cells produce proteins that help them hide from the immune system cells. Immunotherapy works by interfering with that process. For cholangiocarcinoma, immunotherapy might be an option for advanced cancer when other treatments haven’t helped.

- Heating cancer cells. Radiofrequency ablation uses electric current to heat and destroy cancer cells. Using an imaging test as a guide, such as ultrasound, the doctor inserts one or more thin needles into small incisions in your abdomen. When the needles reach the cancer, they’re heated with an electric current, destroying the cancer cells.

- Biliary drainage. Biliary drainage is a procedure to restore the flow of bile. It can involve bypass surgery to reroute the bile around the cancer or stents to hold open a bile duct being collapsed by cancer. Biliary drainage helps relieve signs and symptoms of cholangiocarcinoma.

- Clinical trials. Clinical trials are studies to test new treatments, such as new drugs and new approaches to surgery. If the treatment being studied proves to be safer and more effective than are current treatments, it can become the new standard of care. Clinical trials can’t guarantee a cure, and they might have serious or unexpected side effects. On the other hand, cancer clinical trials are closely monitored to ensure they’re conducted as safely as possible. They offer access to treatments that wouldn’t otherwise be available to you. For people looking to continue to try to treat the cancer, taking part in clinical trials of newer treatments may be an option. This way patients can get the best treatment available now and may also get the treatments that are thought to be even better. Talk to your doctor about what clinical trials might be appropriate for you.

- Palliative therapy.Palliative care is specialized medical care that focuses on providing relief from pain and other symptoms of a serious illness. Palliative care specialists work with you, your family and your other doctors to provide an extra layer of support that complements your ongoing care. Palliative care can be used while undergoing aggressive treatments, such as surgery.When palliative care is used along with other appropriate treatments — even soon after your diagnosis — people with cancer may feel better and may live longer.Palliative care is provided by teams of doctors, nurses and other specially trained professionals. These teams aim to improve the quality of life for people with cancer and their families. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care or end-of-life care.

Based on your treatment options, you might have different types of doctors on your cancer care team. These might include:

- A surgeon or a surgical oncologist: a surgeon who specializes in cancer treatment

- A radiation oncologist: a doctor who uses radiation to treat cancer

- A medical oncologist: a doctor who uses chemotherapy and other medicines to treat cancer

- A gastroenterologist (GI doctor): a doctor who treats diseases of the digestive system

- A hepatologist: a doctor who treats disease of the liver and bile ducts

Because cholangiocarcinoma is a very difficult type of tumor to treat, don’t hesitate to discuss all of your treatment options, including their goals and possible side effects, with your doctors to help make the decision that best fits your needs. It’s also very important to ask questions if there is anything you’re not sure about. If you have any doubts, get a second opinion.

Bile duct cancer surgery

There are 2 general types of surgery for bile duct cancer:

- Potentially curative surgery (resectable and unresectable)

- Palliative surgery.

The following types of surgery are used to treat bile duct cancer:

- Removal of the bile duct: This surgical procedure is done to remove part of the bile duct if the tumor is small and is in the bile duct only. Lymph nodes are removed and tissue from the lymph nodes is viewed under a microscope to see if there is cancer.

- Partial hepatectomy: This is a surgical procedure to remove the part of the liver where cancer is found. The part removed may be a wedge of tissue, an entire lobe, or a larger part of the liver, along with some normal tissue around it.

- Whipple procedure: During this surgical procedure the head of the pancreas, the gallbladder, part of the stomach, part of the small intestine, and the bile duct are removed. Enough of the pancreas is left to make digestive juices and insulin.