Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome

Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome also known as purpura fulminans, is a potentially lethal condition resulting from the failure of the adrenal glands to function normally as a result of bleeding into the adrenal gland or acute hemorrhagic necrosis of the adrenal glands 1. Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome is a rare clinical condition first described by Rupert Waterhouse and Carl Friderichsen as bilateral adrenal hemorrhage in the setting of bacterial sepsis among children in the first decade of the 20th century 2. Over the years, there have been reports of bilateral adrenal hemorrhage in association with multiple causes, including various systemic bacterial and viral infections. Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome has thus been used as a broader clinical term to address the adrenal insufficiency associated with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage. Although the adrenal insufficiency is mainly a feature in those with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, there have been instances where the adrenal insufficiency occurred in unilateral hemorrhage. In these situations, the opposite adrenal gland was exhausted, i.e., the cortical lipoid was reduced or absent 3.

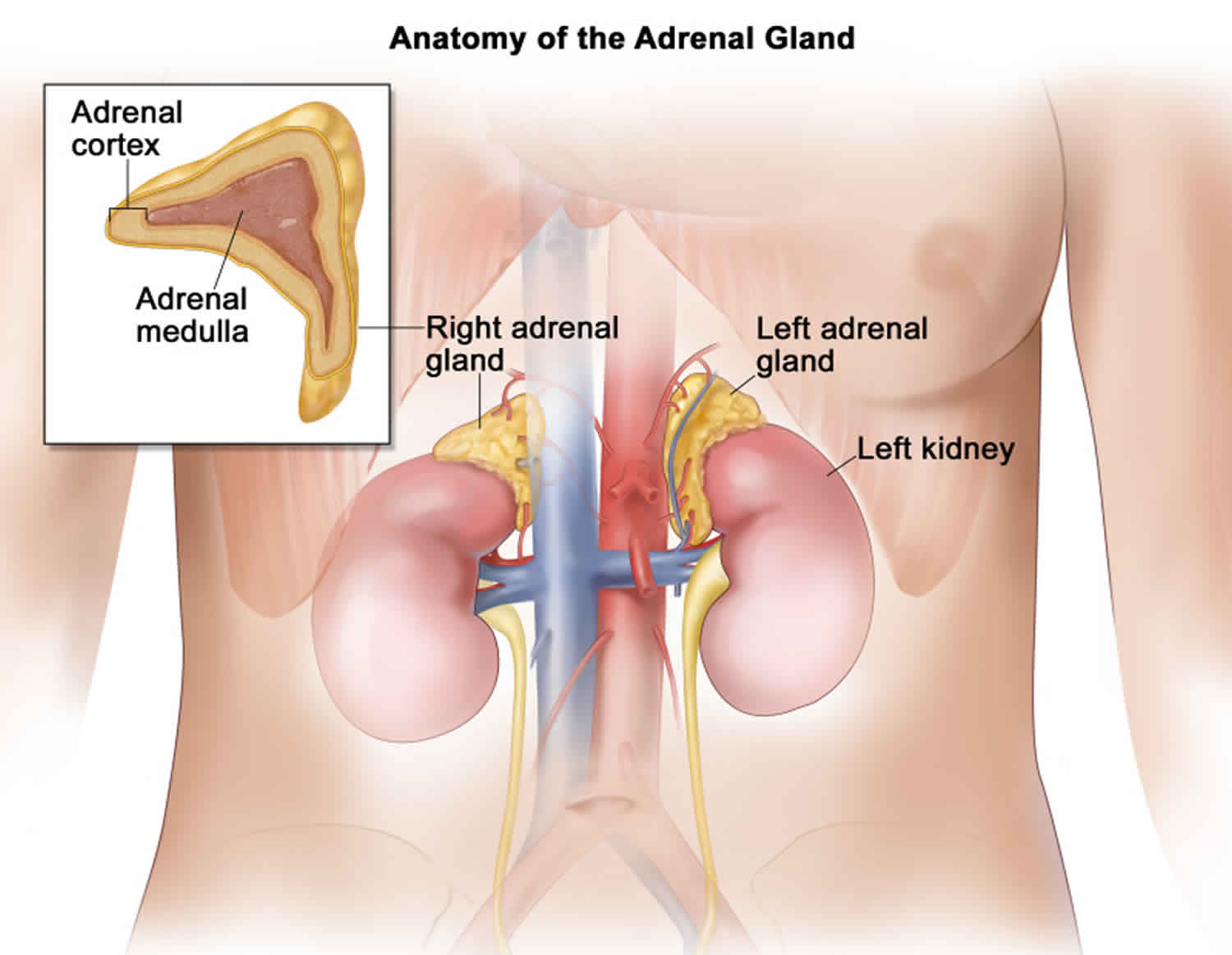

The adrenal glands are two triangle-shaped glands. One gland is located on top of each kidney. The adrenal glands produce and release different hormones that the body needs to function normally. The adrenal glands can be affected by many diseases, such as infections like Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome.

Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome is caused by severe infection with meningococcus bacteria (Neisseria meningitidis) or other severe infection from bacteria, such as 4:

- Group B streptococcus

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Staphylococcus aureus

Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome is a rare condition seen in about 1 percent of routine autopsies 5. No such prevalence studies have taken place so far. It is more common in children compared to adults.

Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome is fatal unless treatment for the bacterial infection is started right away and glucocorticoid drugs are given.

Treatment involves giving antibiotics as soon as possible to treat the bacterial infection. Glucocorticoid medicines will also be given to treat adrenal gland problem. Supportive treatments will be needed for other symptoms.

Figure 1. Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome rash (purpuric rash)

Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome causes

Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome was first described in cases of Neisseria meningitidis sepsis. Over the years, several bacterial and viral causes have correlated, which include and are not limited to, Streptococcus pneumonia 6, Hemophilus influenzae 6, Escherichia coli 7, Staphylococcus aureus 8, Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus 9, Capnocytophaga canimorsus 10, Enterobacter cloacae 11, Pasteurella multocida 12, Plesiomonas shigelloides 13, Neisseria gonorrhoeae 14 and Moraxella duplex 15. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage has also been reported with Rickettsia rickettsii 16, Bacillus anthracis 16, Treponema pallidum 16, Legionella pneumophila 16, and viral infections including Cytomegalovirus, Parvovirus B19, Epstein-Barr virus, and Varicella zoster virus 17. In a study by Margaretten et al. 18 performed in 51 children who died due to sepsis and bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, Pseudomonas aeruginosa was the most common pathogen identified. While another study by Guarner et al. 16 showed Neisseria meningitidis as the most common bacteria associated with adrenal hemorrhage. Other risk factors associated with Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome include the use of anticoagulants, thrombocytopenia, hypercoagulable states as heparin-induced thrombocytopenia 19 and antiphospholipid syndrome 7, trauma to the adrenals, postoperative state.

In a 25-year-study done at Mayo Clinic, trauma was the reported cause of adrenal hemorrhage in 4 out of 141 cases (2.8%). The hemorrhage was bilateral in 2 cases 20. While in another study done over a 10-year-period, trauma was the etiology of adrenal hemorrhage in 28.7 % of cases. All of the patients but 1 had unilateral adrenal hemorrhage 21.

3 (2.1%) patients experienced adrenal hemorrhage associated with anticoagulant therapy in the 25-year study 20. adrenal hemorrhage as a complication of chronic anticoagulation in patients receiving warfarin alone without antiplatelet therapy was uncommon (5.4%, n=6). International normalized ratio (INR) among these patients were variable (mean = 3.13) 21.

In the same 25-year-study, hemorrhage associated with heparin associated thrombocytopenia (HAT) and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome was present in 20 patients (14.2%). Twelve patients were shown to have a circulating lupus anticoagulant. Ten patients had heparin associated thrombocytopenia, and 2 of them had lupus anticoagulant as well 20. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) comprised 9.6 % (n=11) of the total cohort in the other study; 10 of them (91%) developed heparin-induced thrombocytopenia-related adrenal hemorrhage in the postoperative setting. All but one patient with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia had bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, and all these ten patients exhibited acute adrenal insufficiency clinically 21.

Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome pathophysiology

Although the pathophysiology leading to adrenal hemorrhage are unclear in nontraumatic cases, various theories have been postulated to describe the adrenal hemorrhage seen in Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome. Available evidence has implicated adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), adrenal vein spasm and thrombosis, and the normally limited venous drainage of the adrenal in the pathogenesis of Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome 22.

The adrenal gland has a rich arterial supply, in contrast to its limited venous drainage, which is critically dependent on a single vein. There are 50-60 small adrenal branches from 3 main adrenal arteries that form a subcapsular plexus. This plexus drains into the medullary sinusoids through only a few venules. So any cause leading to an increase in the adrenal venous pressure would lead to intraglandular hemorrhage 2.

Furthermore, in stressful situations, there is an increased synthesis of cortisol, including adrenaline and ACTH secretion. The increased serum adrenocorticotrophin (ACTH) raises adrenal blood flow that may exceed the limited venous drainage capacity of the organ and lead to hemorrhage. This situation is further accentuated by platelet aggregation in the adrenal veins induced by adrenaline 23.

Other theories described to explain the hemorrhage include toxin-mediated vasculitis and coagulopathy in association with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). In an experiment done by Levin and Cluff, endotoxin could induce adrenal hemorrhage only when there was an increased activity of the adrenal gland, which suggested that the increased metabolic activity associated with an increase in the production of corticosteroids was needed for the endotoxin to induce hemorrhage in the gland 24. In the study by Guarner J, et al. 16, various amounts of bacteria and bacterial antigens were seen at the site of hemorrhage in 79% of cases while the remaining 21% cases were not associated with bacterial antigens. However, even among those with antigens, a correlation between the amount of adrenal hemorrhage and the number of bacteria and bacterial antigens could not be established. Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) may lead to venous thrombosis in the adrenal gland with consequent hemorrhage into the gland. But multiple cases of Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome have been reported without accompanying DIC.

Regardless of the precise mechanisms, extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage commonly leads to acute adrenal insufficiency and adrenal crisis, unless it is recognized and treated promptly.

Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome symptoms

Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome symptoms and signs usually come on very suddenly. They are due to the bacteria growing (multiplying) inside the body. Symptoms include:

- Fever and chills

- Joint and muscle pain

- Headache

- Vomiting

Infection with bacteria causes bleeding throughout the body, which causes:

- Bodywide rash

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in which small blood clots cut off blood supply to the organs

- Septic shock

Bleeding into the adrenal glands causes adrenal crisis, in which not enough adrenal hormones are produced. This leads to symptoms such as:

- Dizziness, weakness

- Very low blood pressure

- Very fast heart rate

- Confusion or coma

Patients may present suddenly or in the background of ongoing infection with symptoms and signs suggestive of adrenal insufficiency. The principal manifestation of Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome is shock. Patients often have nonspecific symptoms like rapid onset headache, fever, weakness, fatigue, abdominal or flank pain, anorexia, nausea or vomiting, confusion, or disorientation.

On abdominal examination, rigidity or rebound tenderness may be present. Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome associated with meningococcemia characteristically demonstrates petechial rash, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), purpura fulminans along with neurological manifestations seen in meningitis. The petechial rash usually develops on the trunk and lower portions of the body but can develop over mucous membranes, as well. The rash can coalesce to form larger purpura and ecchymoses. The petechiae usually relate to the degree of thrombocytopenia. Thus the clinician must be vigilant about these rashes as they can be of value in anticipating bleeding complications due to DIC.

It is challenging to diagnose Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome, especially in the setting of ongoing sepsis, which may masquerade as septic shock. Surprisingly hypotension precedes shock only in approximately half of all patients 25.

Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome diagnosis

Your health care provider will perform a physical examination and ask about your symptoms.

Blood tests will be done to help confirm if the infection is caused by bacteria. Tests may include:

- Blood culture

- Complete blood count with differential

- Blood clotting studies

If your doctor suspects the infection is caused by meningococcus bacteria, other tests that may be done include:

- Lumbar puncture to get a sample of spinal fluid for culture

- Skin biopsy and Gram stain

- Urine analysis

Tests that may be ordered to help diagnose acute adrenal crisis include:

- ACTH (cosyntropin) stimulation test

- Cortisol blood test

- Blood sugar

- Potassium blood test

- Sodium blood test

- Blood pH test

When Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome is suspected, complete blood work is required. Fall in hemoglobin and hematocrit levels suggest some form of occult bleeding. Leukocytosis may be present because of underlying bacterial infection. Low mineralocorticoid levels lead to hyponatremia and hyperkalemia. Hyponatremia also occurs due to the Syndrome of inappropriate diuretic hormone (SIADH) caused by cortisol deficiency. Volume contraction with accompanying prerenal azotemia may also be a feature. However, the absence of these electrolyte derangements should not exclude the diagnosis. Hypoglycemia, attributed to decreased glucocorticoid, tends to occur in Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome but is not severe, and it is readily correctable. Arterial Blood Gas analysis reveals metabolic acidosis.

Levels of plasma adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), cortisol, aldosterone, and renin activity should be obtained to assess adrenal function. There is a decrease in cortisol level with a rise in ACTH level, a decrease in aldosterone level, and a rise in renin level, features consistent with primary adrenal insufficiency. If the diagnosis remains in doubt, one may administer cosyntropin (ACTH) to assess the adrenal function. CT scan is often used to evaluate adrenal hemorrhage in stable patients. Unstable patients may require an ultrasound at the bedside. Electrocardiography is also necessary to assess any changes in rhythm secondary to hyperkalemia.

Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome differential diagnosis

The diagnosis of Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome requires a high degree of suspicion. With the ongoing bacterial infection, it is highly likely to be confused with septic shock. Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome should be mainly in mind if the shock does not respond to intravenous fluids and vasopressors. Hypotension with low body fluid, hyponatremia, and prerenal azotemia are also features of hypovolemia. So Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome may be confused with hypovolemic shock, especially in the absence of elements of bacterial infection and vomiting as a predominant symptom.

Other conditions presenting as an adrenal crisis merit consideration as well. In neonates, congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency may present as an adrenal crisis within the first few days to weeks of life. Infants with obstructive uropathy, pyelonephritis, or tubulointerstitial nephritis may also present with salt-losing crises with vomiting, hyponatremia, and hyperkalemia 26.

Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome treatment

Patients with Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome present with sepsis. A blood sample should be drawn, and treatment started immediately before obtaining the results 2. Management includes supportive therapy for sepsis with volume resuscitation, appropriate antibiotic coverage, vasopressor to ensure end-organ perfusion, and other supportive care. A bolus of D5 NS (5% dextrose with 0.9 % normal saline) 20 ml/kg is given over 1 hour so that underlying hypoglycemia is also corrected. If shock is persistent, repeat NS up to a total of 60 ml/kg in 1 hour. Hypoglycemia is treatable by giving 2 to 4 ml/kg of 25% dextrose as a bolus. Steroid replacement is in the form of hydrocortisone, given in the dose of 50 to 100 mg/m^2 as a bolus. The dose of hydrocortisone based on age is 25 mg for children up to 3 years, 50 mg for those from 3 to 12 years, and 100 mg for 12 years and older. The same dose of steroid as a bolus is given over 24 hours, either continuously or in four divided doses.

Mineralocorticoid replacement is not needed acutely because it takes a long time to show its sodium-retaining effects. The decreased production of antidiuretic hormone due to hydrocortisone administration along with normal saline infusion helps correct hyponatremia. In most instances, hyperkalemia improves with fluids and hydrocortisone. Rarely, one may need to administer insulin and glucose, especially if hyperkalemia is severe and symptomatic. The monitoring of electrolytes and water balance is essential throughout the treatment. Once the crisis is well controlled, the maintenance dose of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid gets administered regularly.

Conservative management is the recommended approach in cases of traumatic adrenal hemorrhage in the absence of ongoing bleeding 27. Conservative management includes supportive care, hematocrit monitoring, and blood transfusion as needed. In non-operative management, follow-up imaging is essential to assess the resolution of adrenal hematoma. This imaging also helps in differentiating the benign adrenal hematoma from any adrenal mass that would require surgery.

Operative management in the form of angioembolization of one of the vessels supplying the adrenal gland may be necessary to control the ongoing bleeding 28. In a study by Mehrazin 29, surgical exploration was carried out in 3.8 % of cases of traumatic adrenal hemorrhage. Among those requiring surgical exploration, the rate of adrenalectomy was 3.1%.

Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome prognosis

The prognosis of Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome varies according to the severity of illness. Approximately 15 % of patients with significant acute bilateral adrenal bleeding have a fatal outcome. The case fatality rate is almost 50 % in cases of delay in diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Although the mortality is high with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, patients do recover with appropriate management on time. Those who recover need treatment with mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid depending on their electrolyte status and response to the treatment. Although the recovery is unpredictable, research has also shown that those with adrenal hemorrhage can regain some degree of adrenal function after the acute presentation 20. There are no randomized clinical studies to tell the duration of the treatment exactly. So, close follow-up and re-evaluation are necessary. A few long term follow-up studies have shown that recovery may be possible in some cases that no longer require glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement 30.

References- Ventura Spagnolo E, Mondello C, Roccuzzo S, et al. A unique fatal case of Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome caused by Proteus mirabilis in an immunocompetent subject: Case report and literature analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(34):e16664. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000016664 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6716737

- Karki BR, Sedhai YR, Bokhari SRA. Waterhouse-Friderichsen Syndrome. [Updated 2019 Dec 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551510

- Knight B. Sudden unexpected death from adrenal haemorrhage. Forensic Sci. Int. 1980 Nov-Dec;16(3):227-9.

- Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000609.htm

- Xarli VP, Steele AA, Davis PJ, Buescher ES, Rios CN, Garcia-Bunuel R. Adrenal hemorrhage in the adult. Medicine (Baltimore). 1978 May;57(3):211-21

- Fox B. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and the Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome. Arch. Dis. Child. 1971 Oct;46(249):680-5.

- Khwaja J. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage in the background of Escherichia coli sepsis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2017 Mar 17;11(1):72.

- Adem PV, Montgomery CP, Husain AN, Koogler TK, Arangelovich V, Humilier M, Boyle-Vavra S, Daum RS. Staphylococcus aureus sepsis and the Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005 Sep 22;353(12):1245-51.

- Hamilton D, Harris MD, Foweraker J, Gresham GA. Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome as a result of non-meningococcal infection. J. Clin. Pathol. 2004 Feb;57(2):208-9.

- Cooper JD, Dorion RP, Smith JL. A rare case of Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus in an immunocompetent patient. Infection. 2015 Oct;43(5):599-602.

- Pode-Shakked B, Sadeh-Vered T, Kidron D, Kuint J, Strauss T, Leibovitch L. Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome complicating fulminant Enterobacter cloacae sepsis in a preterm infant: the unresolved issue of corticosteroids. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2014 Apr;33(2):104-8.

- Ip M, Teo JG, Cheng AF. Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome complicating primary biliary sepsis due to Pasteurella multocida in a patient with cirrhosis. J. Clin. Pathol. 1995 Aug;48(8):775-7.

- Curti AJ, Lin JH, Szabo K. Overwhelming post-splenectomy infection with Plesiomonas shigelloides in a patient cured of Hodgkin’s disease. A case report. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1985 Apr;83(4):522-4.

- Swierczewski JA, Mason EJ, Cabrera PB, Liber M. Fulminating meningitis with Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome due to Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1970 Aug;54(2):202-4.

- Lewis JF, Marshburn ET, Singletary HP, O’Brien S. Fatal meningitis due to Moraxella duplex: report of a case with Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome. South. Med. J. 1968 May;61(5):539-41.

- Guarner J, Paddock CD, Bartlett J, Zaki SR. Adrenal gland hemorrhage in patients with fatal bacterial infections. Mod. Pathol. 2008 Sep;21(9):1113-20.

- Heitz AFN, Hofstee HMA, Gelinck LBS, Puylaert JB. A rare case of Waterhouse- Friderichsen syndrome during primary Varicella zoster infection. Neth J Med. 2017 Oct;75(8):351-353.

- MARGARETTEN W, NAKAI H, LANDING BH. Septicemic adrenal hemorrhage. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1963 Apr;105:346-51.

- Rosenberger LH, Smith PW, Sawyer RG, Hanks JB, Adams RB, Hedrick TL. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage: the unrecognized cause of hemodynamic collapse associated with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Crit. Care Med. 2011 Apr;39(4):833-8.

- Vella A, Nippoldt TB, Morris JC. Adrenal hemorrhage: a 25-year experience at the Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2001 Feb;76(2):161-8.

- Ketha S, Smithedajkul P, Vella A, Pruthi R, Wysokinski W, McBane R. Adrenal haemorrhage due to heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Thromb. Haemost. 2013 Apr;109(4):669-75.

- Adrenal Hemorrhage. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/126806-overview

- Piccioli A, Chini G, Mannelli M, Serio M. Bilateral massive adrenal hemorrhage due to sepsis: report of two cases. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 1994 Nov;17(10):821-4.

- LEVIN J, CLUFF LE. ENDOTOXEMIA AND ADRENAL HEMORRHAGE. A MECHANISM FOR THE WATERHOUSE-FRIDERICHSEN SYNDROME. J. Exp. Med. 1965 Feb 01;121:247-60.

- Rao RH, Vagnucci AH, Amico JA. Bilateral massive adrenal hemorrhage: early recognition and treatment. Ann. Intern. Med. 1989 Feb 01;110(3):227-35.

- Pai B, Shaw N, Högler W. Salt-losing crisis in infants-not always of adrenal origin. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2012 Feb;171(2):317-21.

- Udobi KF, Childs EW. Adrenal crisis after traumatic bilateral adrenal hemorrhage. J Trauma. 2001 Sep;51(3):597-600.

- Ikeda O, Urata J, Araki Y, Yoshimatsu S, Kume S, Torigoe Y, Yamashita Y. Acute adrenal hemorrhage after blunt trauma. Abdom Imaging. 2007 Mar-Apr;32(2):248-52.

- Mehrazin R, Derweesh IH, Kincade MC, Thomas AC, Gold R, Wake RW. Adrenal trauma: Elvis Presley Memorial Trauma Center experience. Urology. 2007 Nov;70(5):851-5.

- Jahangir-Hekmat M, Taylor HC, Levin H, Wilbur M, Llerena LA. Adrenal insufficiency attributable to adrenal hemorrhage: long-term follow-up with reference to glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid function and replacement. Endocr Pract. 2004 Jan-Feb;10(1):55-61.