West Nile fever

West Nile fever is a mosquito-transmitted disease caused by the West Nile virus that is most commonly spread to people by the bite of an infected female mosquito, primarily involves Culex species mosquitoes, particularly Culex pipiens, Culex tarsalis, and Culex quinquefasciatus 1. The mosquitoes get the West Nile virus when they bite an infected bird. Crows and jays are the most common birds linked to the West Nile virus. But at least 110 other bird species also have the West Nile virus. West Nile virus infection manifests as two clinical syndromes: West Nile fever and West Nile encephalitis 2. West Nile fever is the leading cause of mosquito-borne disease in the continental United States 3. Cases of West Nile fever occur during mosquito season, which starts in the summer and continues through fall. An estimated 70%–80% of people infected with West Nile virus either don’t develop signs or symptoms or have only minor ones, such as a fever, mild headache, weakness, muscle aches and pain (myalgia) or joint pain (arthralgia); gastrointestinal symptoms and a transient maculopapular rash 4, 5. However, less than 1% of infected persons develop a life-threatening neuroinvasive disease that includes inflammation of the spinal cord or brain (meningitis, encephalitis, or acute flaccid paralysis) 6, 7. Risk factors for developing neuroinvasive disease (meningitis, encephalitis, or acute flaccid paralysis) from West Nile virus infection include older age, history of solid organ transplantation, and possibly other immunosuppressive conditions 8, 9, 10.

West Nile virus meningitis is clinically indistinguishable from viral meningitis due to other causes and typically presents with fever, headache, and neck stiffness. West Nile virus encephalitis is a more severe clinical syndrome that usually manifests with fever and altered mental status, seizures, focal neurologic deficits, or movement disorders such as tremor or parkinsonism and carries a mortality rate of approximately 8% 11, 12. West Nile virus acute flaccid paralysis is usually clinically and pathologically identical to poliovirus-associated poliomyelitis, with damage of anterior horn cells, and may progress to respiratory paralysis requiring mechanical ventilation. West Nile virus poliomyelitis often presents as isolated limb paresis or paralysis and can occur without fever or apparent viral prodrome. West Nile virus-associated Guillain-Barré syndrome and radiculopathy have also been reported and can be distinguished from West Nile virus poliomyelitis by clinical manifestations and electrophysiologic testing 13. Rarely, irregular heartbeat (cardiac arrhythmias), inflammation of the heart muscle (myocarditis), breakdown of muscle tissues (rhabdomyolysis), optic neuritis, uveitis, chorioretinitis, inflammation of one or both testicles (orchitis), pancreatitis, and hepatitis have been described in patients with West Nile virus disease.

West Nile virus was first described in 1937 and is named for the West Nile district of Uganda, where it was discovered 14. As of today, the West Nile virus is found in Africa, Europe, Asia, North America, Australia, and the Middle East 15.

West Nile virus was first detected in the United States in the summer of 1999 (there were reports of seven deaths and 62 cases of encephalitis in New York) and since then has been reported in every state — except Hawaii and Alaska — as well as in Canada 8. West Nile virus has been detected in all 50 states, Puerto Rico, and 9 Canadian provinces 16. As of November 1, 2022, a total of 863 cases of West Nile virus disease in people have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Of these, 600 (70%) were classified as neuroinvasive disease (such as meningitis or encephalitis) and 263 (30%) were classified as non-neuroinvasive disease 17.

Most women known to have been infected with West Nile virus during pregnancy have delivered infants without evidence of infection or clinical abnormalities 13. In the best-documented, confirmed congenital West Nile virus infection, the mother developed neuroinvasive West Nile virus disease during the twenty-seventh week of gestation, and her neonate was born with cystic lesions in brain tissue and chorioretinitis 13. One infant who apparently acquired West Nile virus infection through breastfeeding remained asymptomatic 13.

Fortunately, most people infected with West Nile fever do not feel sick. About 1 in 5 people who are infected develop a fever and other symptoms. About 1 out of 150 infected people develop a serious, sometimes fatal, illness.

There are no vaccines to prevent or medications to treat West Nile fever in people. Exposure to mosquitoes where West Nile virus exists increases your risk of getting infected. You can reduce your risk of West Nile fever by using mosquito repellent and wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants that covers your skin to prevent mosquito bites.

Most people recover from West Nile virus without treatment. Mild symptoms of West Nile fever usually resolve on their own. For mild cases, over-the-counter pain relievers can help ease mild headaches and muscle aches. Use caution when giving aspirin to children or teenagers. Children and teenagers recovering from chickenpox or flu-like symptoms should never take aspirin. This is because aspirin has been linked to Reye’s syndrome, a rare but potentially life-threatening condition, in such children.

Seek medical attention right away if you have signs or symptoms of serious infection, such as severe headaches, a stiff neck, disorientation or confusion. Most people who are severely ill need supportive therapy in a hospital with intravenous fluids and pain medication.

Figure 1. West Nile fever mosquito

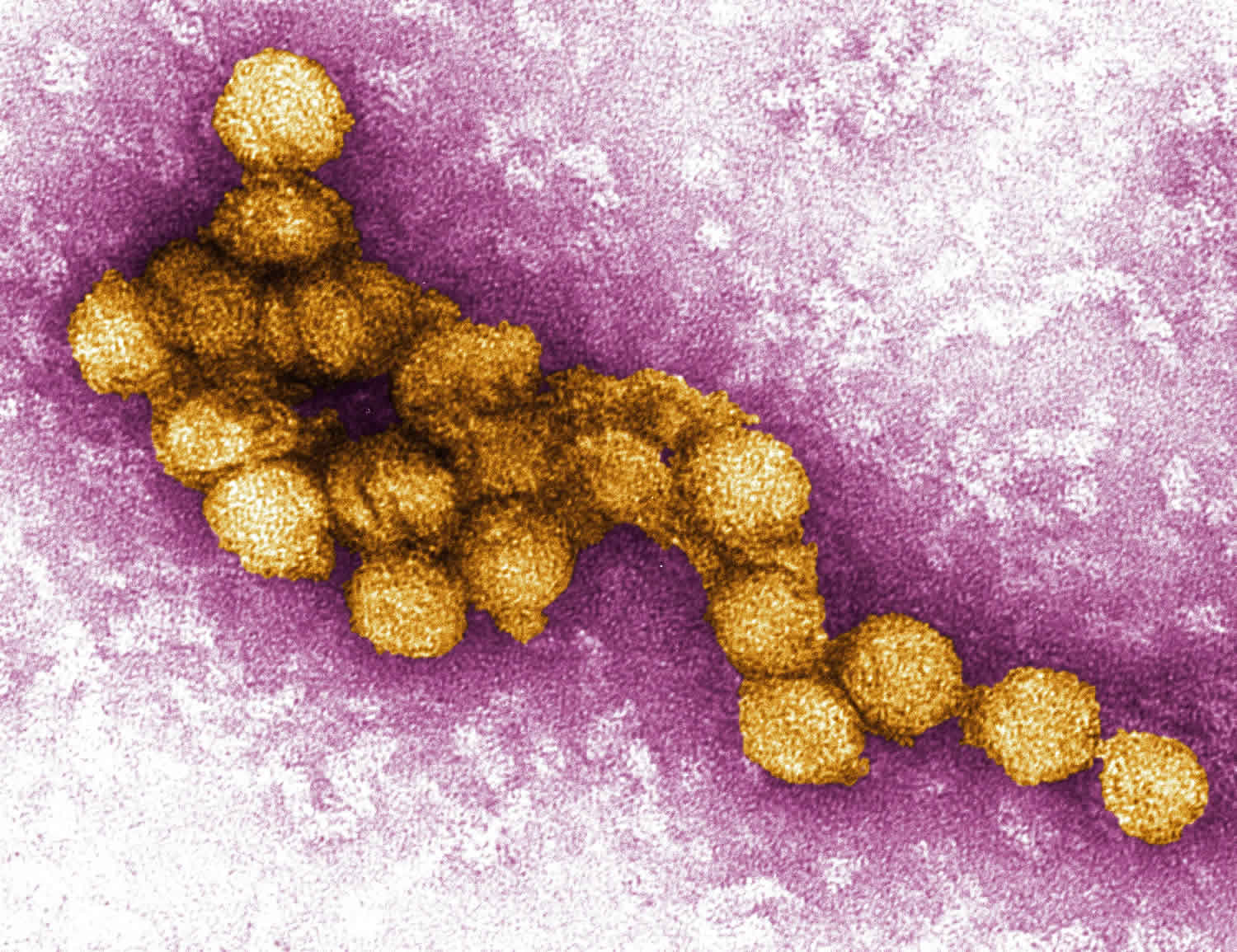

[Source 18 ]Figure 2. West Nile virus

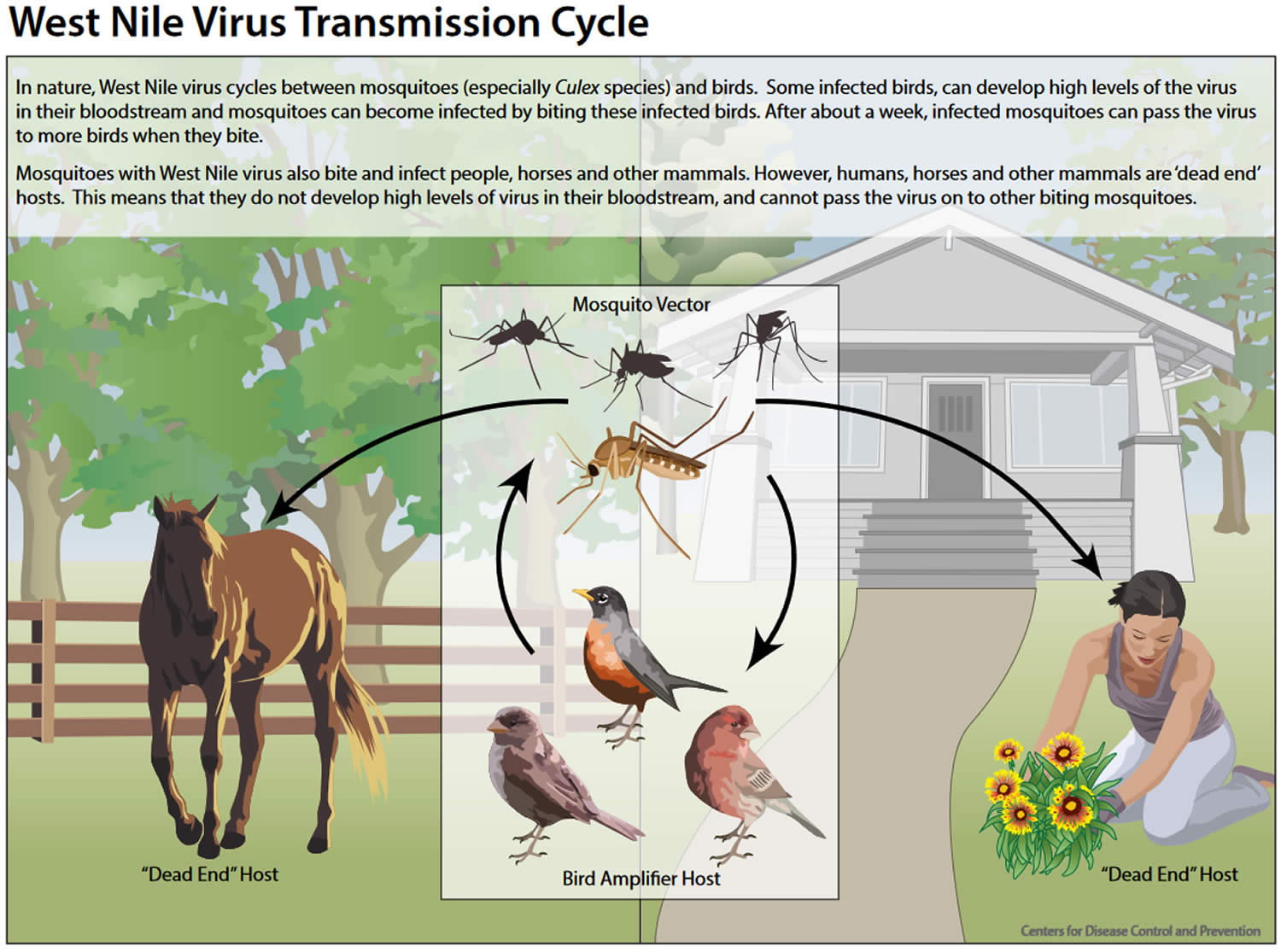

Figure 3. West Nile fever transmission

[Source 19 ]Most people infected with the West Nile fever will have only mild symptoms. However, if any of the following serious symptoms develop, seek medical attention right away:

- High fever

- Severe headache

- Stiff neck

- Confusion

- Muscle weakness

- Vision loss

- Numbness

- Paralysis

- Tremors

- Seizures

- Coma

West Nile fever key points

- Humans get West Nile from the bite of an infected mosquito.

- Usually, the West Nile virus causes mild, flu-like symptoms.

- The virus can cause life-threatening illnesses, such as encephalitis, meningitis, or meningoencephalitis.

- There is no vaccine available to prevent West Nile virus. So, it is important to avoid mosquito bites.

I am pregnant. Am I at higher risk for getting infected with West Nile virus?

No. Pregnant women are not at higher risk for West Nile virus infection.

I am pregnant and was just diagnosed with West Nile virus infection. Is my baby at risk of infection?

A woman who is infected with West Nile virus during pregnancy can possibly transmit the virus to her baby, but the risk is low. Only a few cases of West Nile virus in newborns have been reported. Pregnant women should take precautions to reduce their risk for West Nile virus infection by avoiding mosquitoes, wearing protective clothing, and using insect repellent.

Can West Nile virus be transmitted through breast milk?

Possibly. It appears that West Nile virus may be transmitted through breast milk, although this is likely a rare occurrence. In 2002, a woman developed encephalitis due to West Nile virus from a blood transfusion she received shortly after giving birth. Laboratory analysis showed evidence of West Nile virus in breast milk collected from the mother soon after she became ill. She had been breastfeeding her baby and about 3 weeks after birth the infant tested positive for West Nile virus. Because of the infant’s minimal outdoor exposure, it’s unlikely that infection was from a mosquito. The infant had no symptoms of West Nile virus infection and remained healthy.

Should I continue breastfeeding if I have West Nile virus disease?

Yes. The risk for West Nile virus transmission through breastfeeding is unknown. However, the health benefits of breastfeeding are well established. Therefore, there are no recommendations for a woman to stop breastfeeding because of West Nile virus illness.

If I am pregnant or breastfeeding, should I use insect repellents?

Yes. Protecting yourself from mosquito bites is the only way to prevent infection with West Nile virus. In addition to wearing protective clothing such as long-sleeve shirts and long pants, use insect repellents. Repellents containing active ingredients which have been registered with the EPA are considered safe for pregnant and breastfeeding women. Visit the EPA website to learn more (https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents).

West Nile fever cause

West Nile virus is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus and member of the Flaviviridae family, which also contains the Zika virus, dengue virus, and yellow fever virus. The West Nile virus is genetically related to the Japanese encephalitis family of viruses, which includes a number of closely related viruses that also cause human disease, including Japanese encephalitis in Asia, St. Louis encephalitis in the Americas, and Murray Valley encephalitis in Australia 14. All have a similar transmission cycle, with birds serving as the natural vertebrate host and Culex species mosquitoes serving as the enzootic and/or epizootic vectors 14.

West Nile virus is spread to people from bites of an infected mosquito. Mosquitoes get infected and carry the West Nile virus after biting infected birds. Mosquitoes bite during the day and night. You can’t get infected from casual contact with an infected person or animal.

Most West Nile virus infections happen during warm weather, when mosquitoes are active. The incubation period — the period between when you’re bitten by an infected mosquito and the appearance of signs and symptoms of the illness — generally ranges from 2 to 10 days but ranges from 2 to 14 days and can be several weeks in immunocompromised people 13.

Besides humans, the West Nile virus can infect birds, horses, dogs, and many other mammals. Wild birds may be the optimal hosts for harboring and enabling amplification of the West Nile virus. Humans are considered accidental dead-end hosts due to the low and transient viral levels in the bloodstream (viremia) 6. Additional and rare means of transmission include infected donor blood, organs, breast milk, or transplacental infection 20.

West Nile virus is transmitted when the mosquito feeds, passing infected saliva into the host. The early phase following transmission includes viral replication in dermal dendritic cells and keratinocytes. This phase is followed by the visceral-organ dissemination phase, which includes viral replication in draining lymph nodes, viremia, and spread to the visceral organs. The third and final phase spreads to the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord).

The mechanism for viral central nervous system entry is unclear but may include a direct crossing of the blood-brain barrier, passive transport through the endothelium, infected macrophages crossing the blood-brain barrier or direct axonal retrograde transport. Once in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) the virus primarily induces inflammation and a subsequent loss of neurons within the spinal cord and brainstem gray matter 21.

West Nile fever risk factors

Most cases of West Nile virus in the United States occur June through September. Cases have been reported in all 48 lower states.

Certain things can increase your risk for getting West Nile virus. You are more likely to get the virus if you are exposed to mosquito bites during the summer months.

Most people who are infected have a minor illness and recover fully. But, older people and those with weak immune systems are more likely to get a serious illness from the infection.

Risk of serious infection

Even if you’re infected, your risk of developing a serious West Nile virus-related illness is very small. Less than 1% of people who are infected become severely ill. And most people who do become sick recover fully. You’re more likely to develop a severe or fatal infection based on:

- Age. Being older puts you at higher risk.

- Certain medical conditions. Certain diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure (hypertension) and kidney disease, increase your risk. So does receiving an organ transplant.

West Nile fever transmission

West Nile virus is most commonly spread to people by the bite of an infected female mosquito. Mosquitoes become infected when they feed on infected birds. When a mosquito bites an infected bird, the virus enters the mosquito’s bloodstream and eventually moves into its salivary glands. Infected mosquitoes then spread West Nile virus to people and other animals by biting them, the virus is passed into the host’s bloodstream, where it may cause serious illness (see Figure 3). Humans are considered incidental or dead-end hosts for West Nile virus because they do not develop high enough levels of viremia to allow for transmission when bitten by feeding mosquitoes 6.

In a very small number of cases, West Nile virus has been spread through other routes:

- Exposure in a laboratory setting

- Blood transfusions (blood donors are screened for the West Nile virus, greatly reducing the risk of infection from blood transfusions)

- Organ transplants

- Mother to baby, during pregnancy, delivery, or breast feeding

West Nile virus is NOT spread:

- Through coughing, sneezing, or touching

- By touching live animals

- From handling live or dead infected birds. Avoid bare-handed contact when handling any dead animal. If you are disposing of a dead bird, use gloves or double plastic bags to place the carcass in a garbage can.

- Through eating infected animals, including birds. Always follow instructions for fully cooking meat.

West Nile fever prevention

There is no vaccine to prevent West Nile virus infection. The best way to prevent West Nile disease is to protect yourself from mosquito bites. Use insect repellent, wear long-sleeved shirts and pants, treat clothing and gear, and take steps to control where mosquitoes breed indoors and outdoors. For example, unclog roof gutters; empty unused swimming pools or empty standing water on pool covers; change water in birdbaths and pet bowls regularly; remove old tires or unused containers that might hold water and serve as a breeding place for mosquitoes; install or repair screens on windows and doors.

Prevent Mosquito Bites

Use Insect Repellent

List of insect repellant products approved by the EPA : https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents/find-repellent-right-you

Use Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered insect repellents with one of the active ingredients below. When used as directed, EPA-registered insect repellents are proven safe and effective, even for pregnant and breastfeeding women.

- DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide)

- Picaridin (known as KBR 3023 and icaridin outside the US)

- IR3535

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE)

- Para-menthane-diol (PMD)

- 2-undecanone

Tips for babies and children

- Always follow instructions when applying insect repellent to children.

- Do not use insect repellent on babies younger than 2 months old.

- Instead, dress your child in clothing that covers arms and legs.

- Cover strollers and baby carriers with mosquito netting.

- Do not use products containing oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE) or para-menthane-diol (PMD) on children under 3 years old.

- Do not apply insect repellent to a child’s hands, eyes, mouth, cuts, or irritated skin.

- Adults: Spray insect repellent onto your hands and then apply to a child’s face.

Tips for Everyone

- Always follow the product label instructions.

- Reapply insect repellent as directed.

- Do not spray repellent on the skin under clothing.

- If you are also using sunscreen, apply sunscreen first and insect repellent second.

Natural insect repellents (repellents not registered with EPA)

- Experts do not know the effectiveness of non-EPA registered insect repellents, including some natural repellents.

- To protect yourself against diseases spread by mosquitoes, CDC and EPA recommend using an EPA-registered insect repellent.

- Choosing an EPA-registered repellent ensures the EPA has evaluated the product for effectiveness.

- Visit the EPA website to learn more (https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents).

Protect your baby or child

- Dress your child in clothing that covers arms and legs.

- Cover crib, stroller, and baby carrier with mosquito netting.

Wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants

Treat clothing and gear:

- Use 0.5% permethrin to treat clothing and gear (such as boots, pants, socks, and tents) or buy permethrin-treated clothing and gear.

- Permethrin is an insecticide that kills or repels mosquitoes.

- Permethrin-treated clothing provides protection after multiple washings.

- Read product information to find out how long the protection will last.

- If treating items yourself, follow the product instructions.

Do NOT use permethrin products directly on skin.

Take steps to control mosquitoes indoors and outdoors:

- Use screens on windows and doors. Repair holes in screens to keep mosquitoes outdoors.

- Use air conditioning, if available.

- Stop mosquitoes from laying eggs in or near water.

- Once a week, empty and scrub, turn over, cover, or throw out items that hold water, such as tires, buckets, planters, toys, pools, birdbaths, flowerpots, or trash containers.

- Check for water-holding containers both indoors and outdoors.

Prevent mosquito bites when traveling overseas:

- Choose a hotel or lodging with air conditioning or screens on windows and doors.

- Sleep under a mosquito bed net if you are outside or in a room that does not have screens.

- Buy a bed net at your local outdoor store or online before traveling overseas.

- Choose a WHOPES-approved bed net: compact, white, rectangular, with 156 holes per square inch, and long enough to tuck under the mattress.

- Permethrin-treated bed nets provide more protection than untreated nets.

- Do not wash bed nets or expose them to sunlight. This will break down the insecticide more quickly.

The following can reduce your risk of being bitten:

- use insect repellent – products containing 50% DEET are most effective, but lower concentrations (15-30% DEET) should be used in children, and alternatives to DEET should be used in children younger than two months

- wear loose but protective clothing – mosquitoes can bite through tight-fitting clothes; trousers, long-sleeved shirts, and socks and shoes (not sandals) are ideal

- sleep under a mosquito net – ideally one that has been treated with insecticide

- be aware of your environment – mosquitoes that spread West Nile fever breed in standing water in urban areas

- stay in air-conditioned or well-screened housing. The mosquitoes that carry the West Nile fever virus are most active from dawn to dusk, but they can also bite at night.

West Nile fever symptoms

Most people (8 out of 10) infected with the West Nile virus have no signs or symptoms 4, 5. About 1 in 5 people who are infected develop a fever with other symptoms such as headache, body aches, joint pains, vomiting, diarrhea, or rash. Most people with febrile illness due to West Nile virus recover completely, but fatigue and weakness can last for weeks or months.

Mild infection signs and symptoms

About 20% (1 in 5) of people develop a mild infection called West Nile fever. Common signs and symptoms include:

- Fever

- Headache

- Body aches

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Fatigue

- Skin rash

Serious infection signs and symptoms

In less than 1% of infected people, the virus causes a serious nervous system (neurological) infection, where it may be described as neuroinvasive disease. This may include inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) or inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord (meningitis). Severe illness can occur in people of any age; however, people over 60 years of age are at greater risk for severe illness if they are infected (1 in 50 people). People with certain medical conditions, such as cancer, diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, and people who have received organ transplants, are also at greater risk. About 1 out of 10 people who develop severe illness affecting the central nervous system die.

Signs and symptoms of neurological infections (neuroinvasive disease) include:

- High fever

- Severe headache

- Stiff neck

- Disorientation or confusion

- Coma

- Tremors or muscle jerking

- Seizures

- Partial paralysis or muscle weakness

- Vision loss

- Numbness

Signs and symptoms of West Nile fever usually last a few days. But signs and symptoms of encephalitis or meningitis can linger for weeks or months. Certain neurological effects, such as muscle weakness, can be permanent.

West Nile fever complications

Usually, the West Nile virus causes mild, flu-like symptoms. However, the virus can cause life-threatening illnesses, such as:

- Encephalitis (inflammation of the brain)

- Meningitis (inflammation of the lining of the brain and spinal cord)

- Meningoencephalitis (inflammation of the brain and its surrounding membrane)

- Ocular manifestations:

- vitreitis, chorioretinitis, retinal hemorrhages

- Myocarditis

- Pancreatitis

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Central diabetes insipidus

- Death

West Nile fever diagnosis

If you think you or a family member might have West Nile virus disease, talk with your health care provider.

- Healthcare providers diagnose West Nile virus infection based on:

- Signs and symptoms

- History of possible exposure to mosquitoes that can carry West Nile virus

- Physical exam

- Laboratory testing of blood or spinal fluid

- Your healthcare provider can order tests to look for West Nile virus infection or other infections that can cause similar symptoms, by performing one of the following tests:

- Lab tests. If you’re infected, a blood test may show a rising level of antibodies to the West Nile virus. Antibodies are immune system proteins that attack foreign substances, such as viruses. A blood test may not show antibodies at first; another test may need to be done a few weeks later to show the rising level of antibodies.

- Spinal tap (lumbar puncture). The most common way to diagnose meningitis is to analyze the cerebrospinal fluid surrounding your brain and spinal cord. A needle inserted between the lower vertebrae of your spine is used to remove a sample of fluid for analysis in a lab. The fluid sample may show an elevated white blood cell count — a signal that your immune system is fighting an infection — and antibodies to the West Nile virus. If the sample doesn’t show antibodies, another test may be done a few weeks later.

- Brain tests. In some cases, doctors may order electroencephalography (EEG) — a procedure that measures your brain’s activity — or an MRI scan to help detect brain inflammation.

West Nile virus antibody testing

Laboratory diagnosis is generally accomplished by testing of serum or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to detect West Nile virus-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies. Immunoassays for West Nile virus-specific IgM are available commercially and through state public health laboratories.

West Nile virus-specific IgM antibodies are usually detectable 3 to 8 days after onset of illness and persist for 30 to 90 days, but longer persistence has been documented. Therefore, positive IgM antibodies occasionally may reflect a past infection. If serum is collected within 8 days of illness onset, the absence of detectable virus-specific IgM does not rule out the diagnosis of West Nile virus infection, and the test may need to be repeated on a later sample.

The presence of West Nile virus-specific IgM in blood or CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) provides good evidence of recent infection but may also result from cross-reactive antibodies after infection with other flaviviruses or from non-specific reactivity. According to product inserts for commercially available West Nile virus IgM assays, all positive results obtained with these assays should be confirmed by neutralizing antibody testing of acute- and convalescent-phase serum specimens at a state public health laboratory or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

West Nile virus immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies generally are detected shortly after IgM antibodies and persist for many years following a symptomatic or asymptomatic infection. Therefore, the presence of IgG antibodies alone is only evidence of previous infection and clinically compatible cases with the presence of IgG, but not IgM, should be evaluated for other etiologic agents.

Plaque-reduction neutralization tests (PRNTs) performed in reference laboratories, including some state public health laboratories and CDC, can help determine the specific infecting flavivirus. PRNTs can also confirm acute infection by demonstrating a fourfold or greater change in West Nile virus-specific neutralizing antibody titer between acute- and convalescent-phase serum samples collected 2 to 3 weeks apart.

Other testing for West Nile virus disease

Viral cultures and tests to detect viral RNA (e.g., reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR]) can be performed on serum, CSF, and tissue specimens that are collected early in the course of illness and, if results are positive, can confirm an infection. However, the likelihood of detecting a West Nile virus infection through molecular testing is fairly low.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) can detect West Nile virus antigen in formalin-fixed tissue. Negative results of these tests do not rule out West Nile virus infection. Viral culture, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) can be requested through state public health laboratories or CDC.

West Nile fever treatment

There is no specific treatment for West Nile virus disease; clinical management is supportive 22. Patients with severe meningeal symptoms often require pain control for headaches and antiemetic therapy and rehydration for associated nausea and vomiting. Patients with encephalitis require close monitoring for the development of elevated intracranial pressure and seizures. Patients with encephalitis or poliomyelitis should be monitored for inability to protect their airway. Acute neuromuscular respiratory failure may develop rapidly, and prolonged ventilatory support may be required.

Various drugs have been evaluated or empirically used for West Nile virus disease, as described in a review of the literature for health care providers 23. However, none have shown specific benefit to date 24.

Scientists are investigating interferon therapy — a type of immune cell therapy — as a treatment for encephalitis caused by West Nile virus. Some research shows that people who receive interferon recover better than those who don’t receive the drug, but further study is needed.

West Nile fever prognosis

The prognosis for the vast majority of patients with West Nile virus is excellent, but fatigue, malaise, and weakness can linger for weeks or months 25. Most infected patients are asymptomatic. Those who develop West Nile fever tend to have symptoms of a viral syndrome. It is a self-limited illness with most symptoms lasting up to 10 days. However, the rare and most serious clinical manifestation, neuroinvasive disease, has a mortality of approximately 10 percent. The geriatric population has the highest risk for neuroinvasive West Nile virus and the greatest risk factor for death is neurological involvement 26. Anywhere from 1-4% of patients who develop neurological problems may die. The case-fatality ratio increased with increasing age; 2% of cases among patients aged < 50 years were fatal, compared with 6% of cases among those aged 50–69 years and 21% of those aged ≥70 years 16. These findings were similar to the range of 7%-10% as reported in prior years 12. Significant risk factors associated with development of West Nile encephalitis, as well as increased mortality risk, includes malignancy, or organ transplant recipient status 27. Other important risk factors for development of West Nile encephalitis include hypertension, cardiac disease, diabetes, alcohol abuse, and male sex 10.

Patients who recover from West Nile encephalitis may be left with considerable long-term morbidity and functional deficits 28. About two-thirds of patients who develop paralysis during the West Nile disease course retain significant weakness in that extremity 28. Besides muscle weakness, other, more complex, neurocognitive deficits may develop, including memory loss 29. A small case series showed that symptoms such as fatigue, headache, and myalgias tended to persist at 8 months postinfection, with roughly 40% maintaining their gait or movement symptoms 30. Those with West Nile encephalitis who developed meningitis or encephalitis had better neurological recovery at 8 months than those with acute flaccid paralysis 30.

Recent studies have raised questions about the possible persistence of West Nile virus infection and subsequent kidney disease 31, 32, 33, 34.

References- Turell MJ, Dohm DJ, Sardelis MR, Oguinn ML, Andreadis TG, Blow JA. An update on the potential of north American mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) to transmit West Nile virus. J Med Entomol 2005;42:57–62. 10.1093/jmedent/42.1.57

- West Nile Virus (WNV) Infection and Encephalitis (WNE). https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/234009-overview

- West Nile Virus. https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/index.html

- Mostashari F, Bunning ML, Kitsutani PT, et al. Epidemic West Nile encephalitis, New York, 1999: results of a household-based seroepidemiological survey. Lancet 2001;358:261–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05480-0

- Shimian Zou, Gregory A. Foster, Roger Y. Dodd, Lyle R. Petersen, Susan L. Stramer, West Nile Fever Characteristics among Viremic Persons Identified through Blood Donor Screening, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 202, Issue 9, 1 November 2010, Pages 1354–1361, https://doi.org/10.1086/656602

- Hayes EB, Komar N, Nasci RS, Montgomery SP, O’Leary DR, Campbell GL. Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of West Nile virus disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005 Aug;11(8):1167-73. doi: 10.3201/eid1108.050289a

- Sejvar, J.J. and Marfin, A.A. (2006), Manifestations of West Nile neuroinvasive disease. Rev. Med. Virol., 16: 209-224. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.501

- Nash D, Mostashari F, Fine A, et al. The outbreak of West Nile virus infection in the New York City area in 1999. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1807–14. 10.1056/NEJM200106143442401

- Jean CM, Honarmand S, Louie JK, Glaser CA. Risk factors for West Nile virus neuroinvasive disease, California, 2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007 Dec;13(12):1918-20. doi: 10.3201/eid1312.061265

- Murray K, Baraniuk S, Resnick M, Arafat R, Kilborn C, Cain K, Shallenberger R, York TL, Martinez D, Hellums JS, Hellums D, Malkoff M, Elgawley N, McNeely W, Khuwaja SA, Tesh RB. Risk factors for encephalitis and death from West Nile virus infection. Epidemiol Infect. 2006 Dec;134(6):1325-32. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806006339

- Kramer LD, Ciota AT, Kilpatrick AM. Introduction, Spread, and Establishment of West Nile Virus in the Americas. J Med Entomol. 2019 Oct 28;56(6):1448-1455. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjz151

- Burakoff A, Lehman J, Fischer M, Staples JE, Lindsey NP. West Nile Virus and Other Nationally Notifiable Arboviral Diseases — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:13–17. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6701a3

- West Nile Virus For Healthcare Providers. https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/healthcareproviders/healthCareProviders-ClinLabEval.html

- Duane J. Gubler, The Continuing Spread of West Nile Virus in the Western Hemisphere, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 45, Issue 8, 15 October 2007, Pages 1039–1046, https://doi.org/10.1086/521911

- Nash D, Mostashari F, Fine A, Miller J, O’Leary D, Murray K, Huang A, Rosenberg A, Greenberg A, Sherman M, Wong S, Layton M; 1999 West Nile Outbreak Response Working Group. The outbreak of West Nile virus infection in the New York City area in 1999. N Engl J Med. 2001 Jun 14;344(24):1807-14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106143442401

- McDonald E, Mathis S, Martin SW, Staples JE, Fischer M, Lindsey NP. Surveillance for West Nile Virus Disease – United States, 2009-2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021 Mar 5;70(1):1-15. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7001a1

- West Nile Virus Preliminary Maps & Data for 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/statsmaps/preliminarymapsdata2022/index.html

- Culex Species Eggs, Larvae, Pupae, and Adults. https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/gallery/culex/index.html

- West Nile Virus Transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/resources/pdfs/13_240124_west_nile_lifecycle_birds_plainlanguage_508.pdf

- O’Leary DR, Kuhn S, Kniss KL, Hinckley AF, Rasmussen SA, Pape WJ, Kightlinger LK, Beecham BD, Miller TK, Neitzel DF, Michaels SR, Campbell GL, Lanciotti RS, Hayes EB. Birth outcomes following West Nile Virus infection of pregnant women in the United States: 2003-2004. Pediatrics. 2006 Mar;117(3):e537-45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2024

- Potokar M, Jorgačevski J, Zorec R. Astrocytes in Flavivirus Infections. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Feb 6;20(3):691. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030691

- West Nile Virus For Healthcare Providers. https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/healthcareproviders/healthCareProviders-TreatmentPrevention.html

- West Nile virus disease therapeutics. Review of the literature for healthcare providers. https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/resources/pdfs/WNV-therapeutics-summary-P.pdf

- Hart J Jr, Tillman G, Kraut MA, Chiang HS, Strain JF, Li Y, Agrawal AG, Jester P, Gnann JW Jr, Whitley RJ; NIAID Collaborative Antiviral Study Group West Nile Virus 210 Protocol Team. West Nile virus neuroinvasive disease: neurological manifestations and prospective longitudinal outcomes. BMC Infect Dis. 2014 May 9;14:248. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-248

- Clark MB, Schaefer TJ. West Nile Virus. [Updated 2022 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544246

- Lindsey NP, Staples JE, Lehman JA, Fischer M. Medical risk factors for severe West Nile Virus disease, United States, 2008-2010. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012 Jul;87(1):179-84. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0113

- Lindsey NP, Staples JE, Lehman JA, Fischer M; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance for human West Nile virus disease – United States, 1999-2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2010 Apr 2;59(2):1-17. Erratum in: MMWR Surveill Summ. 2010 Jun 18;59(23):720.

- Petersen LR, Brault AC, Nasci RS. West Nile virus: review of the literature. JAMA. 2013 Jul 17;310(3):308-15. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8042

- Patel H, Sander B, Nelder MP. Long-term sequelae of West Nile virus-related illness: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015 Aug;15(8):951-9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00134-6

- Sejvar JJ, Haddad MB, Tierney BC, Campbell GL, Marfin AA, Van Gerpen JA, Fleischauer A, Leis AA, Stokic DS, Petersen LR. Neurologic manifestations and outcome of West Nile virus infection. JAMA. 2003 Jul 23;290(4):511-5. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.4.511. Erratum in: JAMA. 2003 Sep 10;290(10):1318.

- Nolan MS, Podoll AS, Hause AM, Akers KM, Finkel KW, Murray KO. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and progression of disease over time among patients enrolled in the Houston West Nile virus cohort. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040374

- Steven A. Baty, Katherine B. Gibney, J. Erin Staples, Andrean Bunko Patterson, Craig Levy, Jennifer Lehman, Tricia Wadleigh, Jamie Feld, Robert Lanciotti, C. Thomas Nugent, Marc Fischer, Evaluation for West Nile Virus (WNV) RNA in Urine of Patients Within 5 Months of WNV Infection, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 205, Issue 9, 1 May 2012, Pages 1476–1477, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jis221

- Gibney KB, Lanciotti RS, Sejvar JJ, Nugent CT, Linnen JM, Delorey MJ, Lehman JA, Boswell EN, Staples JE, Fischer M. West nile virus RNA not detected in urine of 40 people tested 6 years after acute West Nile virus disease. J Infect Dis. 2011 Feb 1;203(3):344-7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq057

- Murray K, Walker C, Herrington E, Lewis JA, McCormick J, Beasley DW, Tesh RB, Fisher-Hoch S. Persistent infection with West Nile virus years after initial infection. J Infect Dis. 2010 Jan 1;201(1):2-4. doi: 10.1086/648731