What is polycystic ovaries ?

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome also called Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) is a very common hormonal disorder affecting 4% to 18% (as many as 5 million) of US women and girls of reproductive age 1, 2. It was named Stein—Leventhal Syndrome in 1935 after the authors who described polycystic ovarian morphology in patients suffering from hirsutism, amenorrhoea and infertility 3, 4. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome may have infrequent or prolonged menstrual periods or excess male hormone (androgen) levels 5 and often insulin resistant 2.

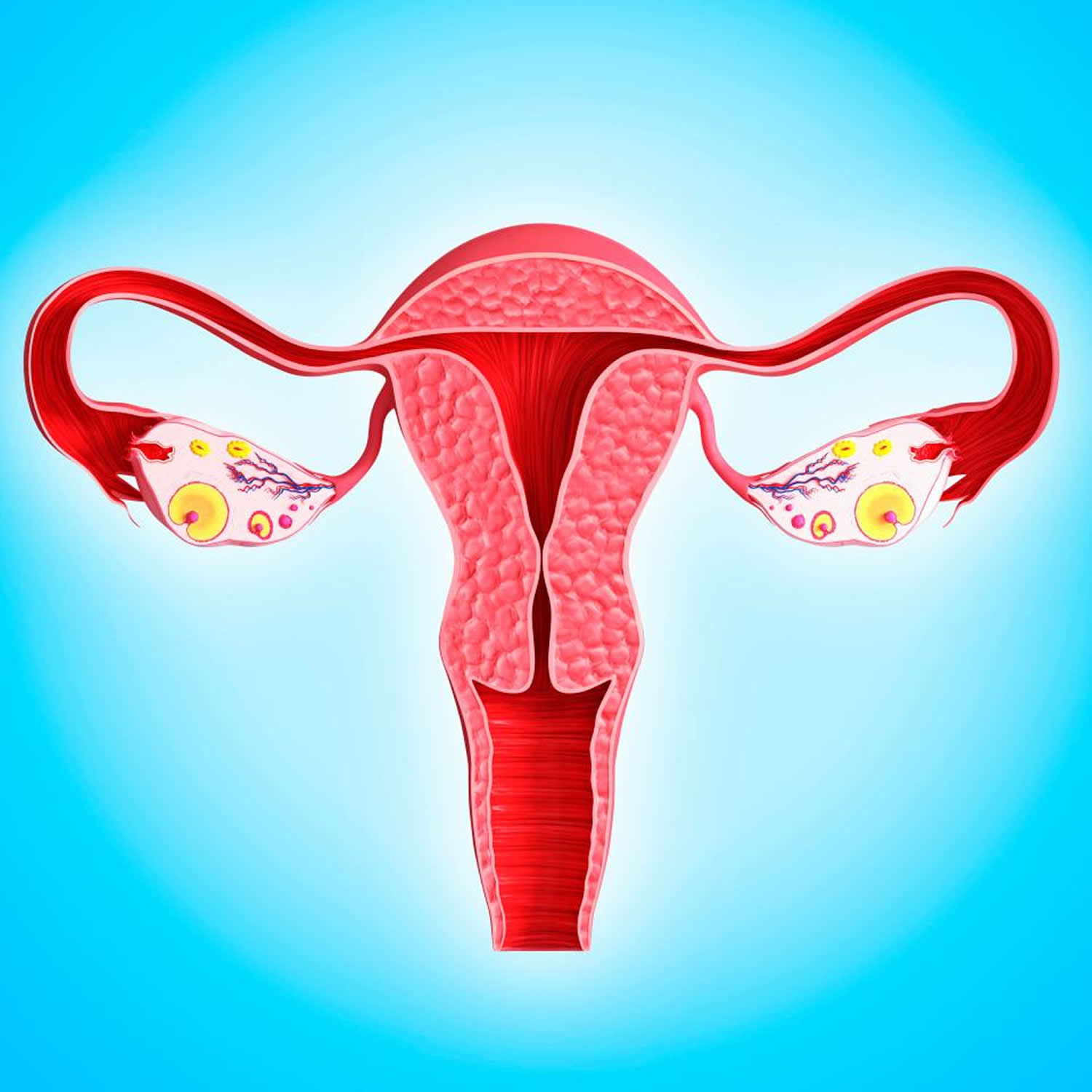

The ovaries may develop numerous small collections of fluid (follicles) and fail to regularly release eggs.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome is characterised by chronic anovulation (ongoing failure or absence of ovulation), clinical and biochemical hyperandrogenism (excess circulating male hormone) causing hirsutism (abnormal growth of hair on a woman’s face and body), acne and obesity 6, 7, 8.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome is a leading cause of infertility 9 and accounts for 90% of anovulatory infertility 10. Besides this, polycystic ovary syndrome impairs endocrine and metabolic functions; 50% to 70% of women with polycystic ovary syndrome have insulin resistance 11, which is far more than for women without polycystic ovary syndrome. Insulin resistance means women with polycystic ovary syndrome don’t respond effectively to insulin, so their bodies keep making more. Excess insulin is thought to increase the level of androgens (male hormones that females also have) produced by the ovaries (egg-producing organs), which can stop eggs from being released (ovulation) and cause irregular periods, acne, thinning scalp hair, and excess hair growth on the face and body 2. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome are at greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome (including hypertension, dyslipidaemia, impaired fibrinolysis and vasodilation), cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease and endometrial cancer 6, 12, 8.

High levels of androgens. Androgens are sometimes called “male hormones,” although all women make small amounts of androgens. Androgens control the development of male traits, such as male-pattern baldness. Women with PCOS have more androgens than normal. Estrogens are also called “female hormones.” Higher than normal androgen levels in women can prevent the ovaries from releasing an egg (ovulation) during each menstrual cycle, and can cause extra hair growth and acne, two signs of PCOS.

High levels of insulin. Insulin is a hormone that controls how the food you eat is changed into energy. Insulin resistance is when the body’s cells do not respond normally to insulin. As a result, your insulin blood levels become higher than normal. Many women with PCOS have insulin resistance, especially those who are overweight or obese, have unhealthy eating habits, do not get enough physical activity, and have a family history of diabetes (usually type 2 diabetes). Over time, insulin resistance can lead to type 2 diabetes.

Can I still get pregnant if I have PCOS ?

Yes. Having PCOS does not mean you can’t get pregnant 13. PCOS is one of the most common, but treatable, causes of infertility in women. In women with PCOS, the hormonal imbalance interferes with the growth and release of eggs from the ovaries (ovulation). If you don’t ovulate, you can’t get pregnant. Your doctor can talk with you about ways to help you ovulate and to raise your chance of getting pregnant.

Figure 1. Polycystic ovaries

Note: The ovaries develop numerous small collections of fluid — called follicles — and may fail to regularly release eggs.

Figure 2. Polycystic ovaries ultrasound – ultrasound scan of a polycystic ovary showing multiple cysts (black) that form when follicles fail to ovulate

Figure 3. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome affects quality of life of women. This is associated with specific features of polycystic ovary syndrome (such as obesity, hirsutism, infertility) and potential mental health problems including depression and allied disorders 14. Depression may be an emotional obstacle to seeking medical advice for the polycystic ovary syndrome, which may further worsen the syndrome 15. The prevalence of depression in women with polycystic ovary syndrome is high; one study has shown it to be four times that of women without polycystic ovary syndrome 16. Even without diagnosed depression or associated mood disorders, women with polycystic ovary syndrome are more anxious and more likely to be in a depressive mood than women without polycystic ovary syndrome 17, 18. The cause of the high prevalence of depression in women with polycystic ovary syndrome is not clear; possibly obesity and insulin resistance play a part 19, 20, 21. Current evidence suggests that following a healthy lifestyle reduces body weight and abdominal fat, reduces testosterone and improves both hair growth, and improves insulin resistance. A healthy lifestyle consists of a healthy diet, regular exercise and achieving and maintaining a healthy weight. There was no evidence that a healthy lifestyle improved cholesterol or glucose levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

The exact cause of polycystic ovary syndrome is unknown 5. Early diagnosis and treatment along with weight loss may reduce the risk of long-term complications such as type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

Causes of polycystic ovaries

The exact causes of polycystic ovary syndrome aren’t known at this time 22, 23, 24, but both weight and family history—which are in turn related to insulin resistance—appear to play a part 2. Moreover, at present most researchers claim that polycystic ovary syndrome is the result of both genetic and environmental factors, but how these factors interact is unknown 22, 25. Polycystic ovary syndrome tends to run in families. Women whose mother or sister has PCOS or type 2 diabetes are more likely to develop polycystic ovary syndrome 2.

Does being Overweight cause Polycystic Ovary Syndrome ?

Since its original description in 1935 by Stein and Leventhal 3, 4, obesity has been recognized as a common feature of the polycystic ovary syndrome. In the United States, some studies report that the prevalence of overweight and obesity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome is as high as 80% 26.

Reproductive disturbances are more common in obese women regardless of the diagnosis of PCOS. Obese women are more likely to have menstrual irregularity and anvolatory infertility than normal-weight women 26. In reproductive-age women, the relative risk of anovulatory infertility increases at a BMI of 24 kg/m2 and continues to rise with increasing BMI 27. Consistent with a pathophysiologic role for obesity, weight reduction can restore regular menstrual cycles in these women 26.

Despite the higher frequency of reproductive abnormalities in obese women, the majority of obese women do not develop hyperandrogenemia and do not have PCOS. In obesity increased androgen production has been reported especially in women with upper-body obesity. However, androgen clearance rates are also increased, and circulating bioavailable androgens remain in the normal range 26. In contrast, in PCOS bioavailable androgen levels are increased 28. This abnormality is further worsened by obesity, especially central obesity, since sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), levels are reduced in this state due to hyperinsulinemia. Furthermore, PCOS is characterized by abnormalities in the gonadotropin hormone releasing hormone, or GnRH, pulse generator leading to preferential increase in luteinising hormone (LH) release over follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) 28. These abnormalities are independent of obesity. Moreover, obese reproductively normal women do not have abnormalities in 24-hour LH and FSH plasma concentrations.

Nonetheless, the prevalence of PCOS among obese reproductive-age women has not been well studied. In a recent study from Spain, PCOS was 5-fold more common among unselected premenopausal overweight or obese women seeking advice for weight loss compared to that of the general population (28.3% vs 5.5%, respectively) 29. In this study, the increased prevalence of PCOS in overweight and obese women was irrespective of the degree of obesity and was independent of the presence or absence of the metabolic syndrome or its features 29. The study demonstrates the prevalence of PCOS may be markedly increased in overweight and obese women. Routine screening by obtaining at least a menstrual history and a careful evaluation for hyperandrogenism may be indicated in these women as well.

How does obesity interact with polycystic ovary syndrome ?

Obesity has a profound effect on both natural and assisted conception—it influences the chance of becoming pregnant and the likelihood of a healthy pregnancy 30. Obesity is associated with increased rates of congenital anomalies (neural tube defects and cardiac defects), miscarriage, gestational diabetes, hypertension, problems during delivery, stillbirth, and maternal mortality 31. Of the 261 deaths reported between 2000 and 2002 to the UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Health, 78 women (35%) were obese, compared with 23% of women in the general population, and of these more than a quarter had a body mass index (BMI) >35 kg/m2 31.

Should obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome lose weight before treatment or should they receive treatment irrespective of the possible outcome ?

Several studies show that weight loss improves the endocrine profile and reproductive outcome in women with polycystic ovary syndrome 32. Even losing 5-10% of total body weight can reduce central fat by up to 30%, improve insulin sensitivity, and restore ovulation 33. Lifestyle modification is a key component of improving reproductive function in overweight anovulatory women with the syndrome 33. Treatment is harder to monitor in obese women as it is difficult to see the number of developing follicles in the ovaries; this increases the risk of multiple ovulation and multiple pregnancy 34. UK guidelines for the management of overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome advise weight loss, preferably to a BMI of <30 kg/m2 before starting drugs for ovarian stimulation 35.

Does polycystic ovary syndrome cause obesity ?

Androgens play an important role in determination of body composition. Men have less body fat with greater distribution of fat in the upper portion of the body (android) compared to women, who tend to accumulate fat in the lower portion of the body (gynoid). Vague 36 first reported that the prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and atherosclerosis was higher in women with android obesity compared to gynoid obesity. Moreover, he observed that the prevalence of android body habitus increases in women after the age of menopause and women with android obesity tend to have features of hyperandrogenism such as hirsutism 36. Women with upper-body obesity have also been noted to have decreased insulin sensitivity and are at higher risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Independent of BMI, women with PCOS have been reported to have a high prevalence of upper-body obesity as demonstrated by increased waist circumference and waist-hip ratio compared to BMI-matched control women. Consistent with these findings, studies using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry have revealed increased accumulation of central fat in women with PCOS 37.

Chronic exposure to higher testosterone levels in women with PCOS may modify body fat distribution in these women. Support for this hypothesis is provided by studies of androgen administration in nonobese female to male transsexuals that lead to increases in visceral fat and adversely impact insulin sensitivity 38. In post-menopausal women exposure to androgens increases visceral fat in both obese and normal-weight women 39. In rats, testosterone administration of a single high dose early in life leads to development of insulin resistance and centralization of adipose tissue mass as an adult 40. It may be that early androgen exposure adversely impacts future body fat distribution with greater accumulation of central fat.

However, few studies have examined visceral fat content in women with PCOS. Studies of isolated abdominal fat cells from women with PCOS have revealed larger-sized cells in both obese and nonobese women with PCOS compared to control women, suggesting a preferential abdominal accumulation of adipose tissue 41. Femoral adipocytes are smaller in obese women with PCOS than reproductively normal women consistent with a shift to android body fat distribution in PCOS women. These observations raise the hypothesis that hyperandrogenemia may contribute to the development of visceral adiposity in PCOS women necessitating further investigation in this area.

Lower fasting levels of the peptide hormone, ghrelin, have been reported in women with PCOS compared to weight-matched control women. Ghrelin is produced by the gastric endocrine cells and has been implicated in regulation of appetite and body weight. Ghrelin levels increase sharply before meals leading to hunger and initiation of food intake and drop after feeding leading to suppression of appetite and satiety. Fasting ghrelin levels are reported to be lower in obese individuals due to chronic positive energy balance. However, there is evidence that ghrelin homeostasis in PCOS may be dysregulated. In addition to lower fasting ghrelin levels, women with PCOS have less marked post-parandial reduction in the level of this hormone, as well as less satiety following a test meal. Lack of suppression of ghrelin following food intake may interfere with meal termination and lead to weight gain in these women 42.

Polycystic ovaries diet

While lifestyle management is recommended as first-line treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome, the optimal dietary composition is unclear. This study 43 compare the effect of different diet compositions on anthropometric, reproductive, metabolic, and psychological outcomes in PCOS. There were subtle differences between diets:

- Greater weight loss for a monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) enriched diet;

- Improved menstrual regularity for a Low−Glycemic Index (GI) diet;

- Greater reductions in insulin resistance, fibrinogen, total, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol for a Low-Carbohydrate or Low−Glycemic Index diet;

- Improved quality of life for a Low−Glycemic Index diet; and

- Improved depression and self-esteem for a High-Protein diet.

Weight loss improved the presentation of PCOS regardless of dietary composition in the majority of studies. Weight loss should be targeted in all overweight women with PCOS through reducing caloric intake in the setting of adequate nutritional intake and healthy food choices irrespective of diet composition.

Polycystic ovaries symptoms and signs

Signs and symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome often develop around the time of the first menstrual period during puberty. Sometimes PCOS develops later, for example, in response to substantial weight gain.

PCOS is a lifelong health condition that reaches far beyond the child-bearing years. As women with PCOS get older, their risk for PCOS complications such as type 2 diabetes and heart disease grows. That’s why lifestyle changes you can stick with are so important.

Signs and symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome vary. A diagnosis of PCOS is made when you experience at least two of these signs:

- Irregular periods. Infrequent, irregular or prolonged menstrual cycles are the most common sign of PCOS. For example, you might have fewer than nine periods a year, more than 35 days between periods and abnormally heavy periods.

- Excess androgen. Elevated levels of male hormone may result in physical signs, such as excess facial and body hair (hirsutism), and occasionally severe acne and male-pattern baldness. Excess hair growth on the face, chest, abdomen, or upper thighs (hirsutism), affects more than 70% of women with PCOS.

- Polycystic ovaries. Multiple small fluid-filled sacs in the ovaries. Your ovaries might be enlarged and contain follicles that surround the eggs. As a result, the ovaries might fail to function regularly.

- Infertility. PCOS is one of the most common causes of female infertility.

- Obesity. Up to 80% of women with PCOS are obese. Obesity associated with PCOS can worsen complications of the disorder.

- Severe acne or acne that occurs after adolescence and does not respond to usual treatments.

- Oily skin.

- Patches of thickened, velvety, darkened skin called acanthosis nigricans.

- Skin tags, which are small excess flaps of skin in the armpits or neck area.

PCOS signs and symptoms are typically more severe if you’re obese.

These clinical features include reproductive manifestations such as reduced frequency of ovulation and irregular menstrual cycles, reduced fertility, polycystic ovaries on ultrasound, and high male hormones such as testosterone which can cause excess facial or body hair growth and acne. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome is also associated with metabolic features and diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk factors including high levels of insulin or insulin resistance and abnormal cholesterol levels.

Obesity is a common finding in PCOS and aggravates many of its reproductive and metabolic features. The relationship between PCOS and obesity is complex, not well understood, and most likely involves interaction of genetic and environmental factors.

Polycystic ovary syndrome is also linked to depression and anxiety, though the connection is unclear. Furhermore, this Cochrane Review 2013 44 found no evidence on the effectiveness and safety of antidepressants in treating depression and other symptoms in women with PCOS.

The endocrine abnormalities in women with polycystic ovary syndrome include raised concentrations of luteinising hormone (LH; seen in about 40% of women), testosterone, and androstenedione, in association with low or normal concentrations of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) 45. Androgen production from the polycystic ovary is driven predominantly by luteinising hormone in slim women and insulin in overweight women 45. The definition of polycystic ovary syndrome recognises obesity as an association and not a diagnostic criterion. Only 40-50% of women with the syndrome are overweight 46, 47.

Insulin resistance is a key pathophysiological abnormality, and women with polycystic ovary syndrome have increased risk of impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and the metabolic syndrome. The longer the interval between menstrual bleeds the greater the degree of insulin resistance 47. Although women with polycystic ovaries are more insulin resistant than weight matched women with normal ovaries, insulin resistance is seen in only 10-15% of slim and 20-40% of obese women with the syndrome 48.

Insulin Resistance

Insulin Resistance is not considered a diagnostic criterion in polycystic ovary syndrome 49. However, it is recognized by many as a common feature in PCOS independent of obesity 50, 51. An estimated prevalence of insulin resistance among polycystic ovary syndrome patients of 60–70% has been reported 52. However, being overweight or obese is common among polycystic ovary syndrome women, affecting up to 88% of these women 53, 54, 55, therefore casting doubt on the role insulin resistance plays in the pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome. Further, clinical quantification of insulin resistance is not accurate enough 48 to enable a better understanding of the role of insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome pathogenesis or to incorporate it into the work up programme of polycystic ovary syndrome patients. However, it is generally acceptable that insulin resistance plays a significant role in polycystic ovary syndrome either directly or through obesity and represents a clinical concern to physicians and patients.

Complications of PCOS can include:

- Infertility

- Gestational diabetes or pregnancy-induced high blood pressure

- Miscarriage or premature birth

- Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) — a severe liver inflammation caused by fat accumulation in the liver

- Metabolic syndrome — a cluster of conditions including high blood pressure, high blood sugar, and abnormal cholesterol or triglyceride levels that significantly increase your risk of cardiovascular disease

- Type 2 diabetes or prediabetes

- Sleep apnea

- Venous thromboembolism 56

- Depression, anxiety and eating disorders

- Abnormal uterine bleeding

- Cancer of the uterine lining (endometrial cancer)

High insulin levels from polycystic ovary syndrome can lead to serious health problems, especially for women who are obese 2:

- Diabetes —more than half of women with polycystic ovary syndrome develop type 2 diabetes by age 40

- Gestational diabetes (diabetes when pregnant)—which puts the pregnancy and baby at risk and can lead to type 2 diabetes later in life

- Heart disease —the risk of heart attack is 4 to 7 times higher compared to women the same age who don’t have PCOS

- High blood pressure —which can damage the heart, brain, and kidneys

- High LDL (“bad”) cholesterol and low HDL (“good”) cholesterol—increasing the risk for heart disease

- Stroke —plaque (cholesterol and white blood cells) clogging blood vessels can lead to blood clots that in turn can cause a stroke.

Endometrial cancer

Recent interest in the long term risks of PCOS has also focused on its possible associations with endometrial cancer. Prolonged anovulation which characterizes the syndrome is considered to be the main mechanism responsible for continual unopposed secretion of oestrogens and consequent increased risk of endometrial carcinoma 57. The known factors which increase the risk of developing endometrial cancer are obesity, longterm use of unopposed oestrogens, nulliparity, infertility, hypertention and diabetes 58, 59. Most of these factors are known also to be associated with PCOS. Endometrial hyperplasia may be a precursor to adenocarcinoma. A precise estimate rate of pregression is practically impossible to be determined, but it estimated that 18% of cases of adenomatous hyperplasia will progress to cancer in the following 2 to 10 years. In women with PCOS intervals between menstruation of more than three months may be associated with endometrial hyperplasia and later carcinoma 57. Evidence from a big study in which 1270 women with chronic anovulation participated, the excess risk of endometrial cancer was identified to be 3.1 60. However a more recent appraisal of the evidence for association between PCOS and endometrial cancer was inconclusive 61. The true risk of endometrial carcinoma in women diagnosed with PCOS has not been clearly defined yet.

Ovarian cancer

There has been much debate and concerns about the risk of ovarian cancer in women with anovulation, particularly because of the extend use of drugs for induction of ovulation to these patients. Several lines of evidence might suggest that there is a connection between PCOS and increased risk of ovarian cancer. The risk appears to be increased in nulliparous women (multiple ovulations), with early menarche and late menopause. Without any evidence based data to support this theory, it may be that inducing multiple ovulations in women with infertility will increase their risk. So, although women with PCOS are expected to be in low risk groups for developing ovarian cancer due to their life time reduced ovulation rate, by using ovulation induction treatments and inducing multifollicular ovulations theoretically an imbalance to their risk for ovarian cancer will be technically created

There are only a few studies addressing the possibility of association of polycystic ovaries and ovarian cancer with conflicting evidence. Large Danish studies suggest that infertility on its own increases the risk of borderline and invasive ovarian tumors 62, 63. Another study linking clomiphene and ovarian cancer suggests that the relative risk for ovarian cancer for women with PCOS is 4.1 compared to controls 64. The large UK study though concludes that the standardized mortality rate for ovarian cancer is only 0.39 65. Even more recent evidence about association between polycystic ovarian syndrome and ovarian malignancy are still conflicting but generally reassuring 66.

Breast cancer

Obesity, hyperandrogenism and infertility are features known to be associated with the development of breast cancer. However studies failed to show any significant increase in the risk of developing breast cancer in women with PCOS 65. On the other hand though, it seems that there is a positive association between PCOS and the presence of family history of breast cancer. In a study of 217 women the proportion of women with positive family history of breast cancer was significantly higher in women with PCOS compared with controls 67.

Polycystic ovaries diagnosis

There’s no test to definitively diagnose PCOS. Your doctor is likely to start with a discussion of your medical history, including your menstrual periods and weight changes. A physical exam will include checking for signs of excess hair growth, insulin resistance and acne.

Your doctor might do a physical exam and different tests 68:

- Physical exam. Your doctor will measure your blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), and waist size. He or she will also look at your skin for extra hair on your face, chest or back, acne, or skin discoloration. Your doctor may look for any hair loss or signs of other health conditions (such as an enlarged thyroid gland).

- A pelvic exam. The doctor visually and manually inspects your reproductive organs for masses, growths or other abnormalities.

- Blood tests. Your blood may be analyzed to measure hormone levels. This testing can exclude possible causes of menstrual abnormalities or androgen excess that mimics PCOS. You might have additional blood testing to measure glucose tolerance and fasting cholesterol and triglyceride levels.

- Pelvic ultrasound. Your doctor checks the appearance of your ovaries and the thickness of the lining of your uterus. A wandlike device (transducer) is placed in your vagina (transvaginal ultrasound). The transducer emits sound waves that are translated into images on a computer screen.

Once other conditions are ruled out, you may be diagnosed with PCOS if you have at least two of the following symptoms 69:

- Irregular periods, including periods that come too often, not often enough, or not at all

- Signs that you have high levels of androgens: Extra hair growth on your face, chin, and body (hirsutism) / Acne / Thinning of scalp hair

- Higher than normal blood levels of androgens

- Multiple cysts on one or both ovaries

If you have a diagnosis of PCOS, your doctor might recommend additional tests for complications. Those tests can include:

- Periodic checks of blood pressure, glucose tolerance, and cholesterol and triglyceride levels.

- Screening for depression and anxiety.

- Screening for obstructive sleep apnea.

Until recently, the diagnosis of PCOS was based on the criteria established by a 1990 NIH/National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development (NIH criteria) conference (Table 1. Diagnostic Criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome) 39.

At the 2003 Rotterdam conference on PCOS, the diagnostic criteria were expanded to include polycystic ovary (PCO) morphology 70. However, this addition to the diagnostic criteria remains controversial because an established minority of women with the biochemical features of the syndrome do not have polycystic ovary (PCO) morphology. Moreover about 25% of asymptomatic women with regular menses have polycystic ovary (PCO) morphology on ultrasound. Many of these women have elevated androgen or luteinizing hormone (LH) levels, but some have normal reproductive function. Furthermore, ovulatory women with polycystic ovary (PCO) and hyperandrogenism may not be as insulin resistant or carry the same increased risk for type 2 diabetes as women diagnosed with PCOS based on the National Institutes Health criteria.

The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in the general population depends on the diagnostic criteria used. In the past, using the National Institutes for Health consensus 71 the definition was more exclusive and population estimates were about 7% 72. Using the more recent Rotterdam consensus 49 the prevalence is estimated to be as high as 20-25% in white women in the UK 73, although symptoms are often mild. The highest reported prevalence was 52% in South Asian immigrants in the United Kingdom, of whom 49% had menstrual irregularity 74. Not all women with polycystic ovaries have the clinical and biochemical features that define the syndrome, and about 20% of women with polycystic ovaries have no symptoms. Women from South Asia living in the UK have symptoms at an earlier age than their white counterparts; they also have greater insulin resistance and more severe symptoms 75.

Table 1. Diagnostic Criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome

| NIH/NICHD Criteria* | Rotterdam Criteria* |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis requires both features: | Diagnosis requires 2 of 3 features: |

| 1. Oligo and/or anovulation | 1. Oligo and/or anovulation |

| 2. Hyperandrogenism Clinical or biochemical | 2. Hyperandrogenism Clinical or biochemical |

| 3. Polycystic ovary morphology** |

Polycystic ovaries treatment

PCOS treatment focuses on managing your individual concerns, such as infertility, hirsutism, acne or obesity. Specific treatment might involve lifestyle changes or medication 76.

Lifestyle changes

Your doctor may recommend weight loss through a low-calorie diet combined with moderate exercise activities. Even a modest reduction in your weight — for example, losing 5 percent of your body weight — might improve your condition. Losing weight may also increase the effectiveness of medications your doctor recommends for PCOS, and can help with infertility.

Medications

To regulate your menstrual cycle, your doctor might recommend:

- Combination birth control pills. Pills that contain estrogen and progestin decrease androgen production and regulate estrogen. Regulating your hormones can lower your risk of endometrial cancer and correct abnormal bleeding, excess hair growth and acne. Instead of pills, you might use a skin patch or vaginal ring that contains a combination of estrogen and progestin.

- Progestin therapy. Taking progestin for 10 to 14 days every one to two months can regulate your periods and protect against endometrial cancer. Progestin therapy doesn’t improve androgen levels and won’t prevent pregnancy. The progestin-only minipill or progestin-containing intrauterine device is a better choice if you also wish to avoid pregnancy.

To help you ovulate, your doctor might recommend:

- Clomiphene (Clomid). This oral anti-estrogen medication is taken during the first part of your menstrual cycle.

- Letrozole (Femara). This breast cancer treatment can work to stimulate the ovaries.

- Metformin (Glucophage, Fortamet, others). This oral medication for type 2 diabetes improves insulin resistance and lowers insulin levels. If you don’t become pregnant using clomiphene, your doctor might recommend adding metformin. If you have prediabetes, metformin can also slow the progression to type 2 diabetes and help with weight loss.

- Gonadotropins. These hormone medications are given by injection.

To reduce excessive hair growth, your doctor might recommend:

- Birth control pills. These pills decrease androgen production that can cause excessive hair growth.

- Spironolactone (Aldactone). This medication blocks the effects of androgen on the skin. Spironolactone can cause birth defect, so effective contraception is required while taking this medication. It isn’t recommended if you’re pregnant or planning to become pregnant.

- Eflornithine (Vaniqa). This cream can slow facial hair growth in women.

- Electrolysis. A tiny needle is inserted into each hair follicle. The needle emits a pulse of electric current to damage and eventually destroy the follicle. You might need multiple treatments.

How do dcotors help women with the polycystic ovary syndrome to ovulate ?

Anovulatory infertility in polycystic ovary syndrome has traditionally been managed with clomifene citrate and then gonadotrophins or laparoscopic ovarian surgery in women who are resistant to clomifene. Clomifene is associated with around an 11% risk of multiple pregnancy 77, so the ovarian response should be carefully monitored with ultrasound 78. Such monitoring is also mandatory when using gonadotrophins, which are indicated for women who have been treated with antioestrogens if they have failed to ovulate, or if their response to clomifene is likely to reduce their chance of conception (such as persistent hypersecretion of luteinising hormone). To prevent overstimulation and multiple pregnancy, standard step-up regimens have been replaced by low dose ones, and strict criteria are used before giving human chorionic gonadotrophin or luteinising hormone, which are needed for release of the eggs (no more than one or two follicles are allowed to develop) 79. Expected pregnancy rates are 20% per cycle and 60-70% after six cycles.

There has been a shift away from inducing ovulation of just one follicle to in vitro fertilisation—this is based on the false premise that in vitro fertilisation has greater cumulative rates of conception. Superovulation for in vitro fertilisation is risky in women with polycystic ovaries because of the potentially life threatening complication of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (although this complication can occur rarely after standard induction of ovulation). Carefully conducted induction of ovulation achieves good cumulative rates of conception, and rates of multiple pregnancy can be minimised by strict adherence to criteria that limit the number of follicles that develop 80.

Insulin sensitising agents, such as metformin, have been investigated because of the association between hyperinsulinaemia and polycystic ovary syndrome. Once thought of as a wonder drug, the accumulating evidence on the efficacy of metformin has been disappointing. Metformin seems to be less effective in significantly obese women (BMI >35). The largest appropriately powered, prospective, randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study set out to evaluate the combined effects of lifestyle modification and metformin in obese anovulatory women with polycystic ovary syndrome and a mean BMI of 38 81. All women were individually assessed by a dietitian to set a realistic goal that could be sustained, with an average reduction in energy intake of 2.09 MJ (500 kcal) a day. As a result, women in both the metformin treated and placebo groups lost weight, but the amount of weight did not differ between the two groups. Menstrual cyclicity increased in women who lost weight, but again this did not differ between the two arms of the study 81. Based on the available evidence, metformin does not replace the need for lifestyle modification among obese and overweight PCOS women. The evidence categorically does not encourage metformin use to help weight loss either although it may be useful in redistributing adiposity according to some evidence 82. The long-term use of metformin to prevent remote complications of PCOS is uncertain and a significant amount of work is needed before a decision can be made on this front.

What are my treatment options for PCOS if I want to get pregnant ?

You have several options to help your chances of getting pregnant if you have PCOS 13:

- Losing weight. If you are overweight or obese, losing weight through healthy eating, including eating the right amount of calories for you, and regular physical activity can help make your menstrual cycle more regular and improve your fertility.

- Medicine. After ruling out other causes of infertility in you and your partner, your doctor might prescribe medicine to help you ovulate, such as clomiphene (Clomid).

- In vitro fertilization (IVF). IVF may be an option if medicine does not work. In IVF, your egg is fertilized with your partner’s sperm in a laboratory and then placed in your uterus to implant and develop. Compared to medicine alone, IVF has higher pregnancy rates and better control over your risk for twins and triplets (by allowing your doctor to transfer a single fertilized egg into your uterus).

- Surgery. Surgery is also an option, usually only if the other options do not work. The outer shell (called the cortex) of ovaries is thickened in women with PCOS and thought to play a role in preventing spontaneous ovulation. Ovarian drilling is a surgery in which the doctor makes a few holes in the surface of your ovary using lasers or a fine needle heated with electricity. Surgery usually restores ovulation, but only for six to eight months.

How does PCOS affect pregnancy ?

PCOS can cause problems during pregnancy for you and for your baby. Women with PCOS have higher rates of 83:

- Miscarriage

- Gestational diabetes

- Preeclampsia

- Cesarean section (C-section)

Your baby also has a higher risk of being heavy (macrosomia) and of spending more time in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

How can I prevent problems from PCOS during pregnancy ?

You can lower your risk of problems during pregnancy by:

- Reaching a healthy weight before you get pregnant. Use this interactive tool (link is external) to see your healthy weight before pregnancy and what to gain during pregnancy.

- Reaching healthy blood sugar levels before you get pregnant. You can do this through a combination of healthy eating habits, regular physical activity, weight loss, and medicines such as metformin.

- Taking folic acid. Talk to your doctor about how much folic acid you need.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. The effect of a healthy lifestyle for women with polycystic ovary syndrome. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0014488/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PCOS and Diabetes, Heart Disease, Stroke. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/spotlights/pcos.html

- The Stein-Leventhal syndrome. LEVENTHAL ML. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1958 Oct; 76(4):825-38. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13583027/

- Stein I.F., Leventhal M. (1935) Amenorrhoea associated with bilateral polycystic ovaries. Am J Obstet Gynecol 29: 181–191.

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pcos/home/ovc-20342146

- Chittenden BG, Fullerton G, Maheshwari A, Bhattacharya S. Polycystic ovary syndrome and the risk of gynaecological cancer: a systematic review. Reproductive Biomedicine Online 2009;19:398-405. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19778486

- Hart R, Hickey M, Franks S. Definitions, prevalence and symptoms of polycystic ovaries and polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2004;18:671-83. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15380140

- Meyer C, McGrath BP, Teede HJ. Overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome have evidence of subclinical cardiovascular disease. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2005;90:5711-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16046590

- Boomsma CM, Fauser BC, Macklon NS. Pregnancy complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine 2008;26:72-84. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18181085

- Balen AH, Rutherford AJ. Managing anovulatory infertility and polycystic ovary syndrome. BMJ 2007;335:663-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1995495/

- Nestler JE. Insulin regulation of human ovarian androgens. Human Reproduction 1997;12:53-62. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9403321

- Lobo RA. Priorities in polycystic ovary syndrome. The Medical Journal of Australia 2001;174:554-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11453323

- The Office on Women’s Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Polycystic ovary syndrome. https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/polycystic-ovary-syndrome

- McCook JG, Reame NE, Thatcher SS. Health-related quality of life issues in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 2005;34(1):12-20.

- Herbert D, Lucke J, Dobson A. Depression: an emotional obstacle to seeking medical advice for infertility. Fertility and Sterility 2010;94(5):1817-21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20047740

- Hollinrake E, Abreu A, Maifeld M, Van Voorhis BJ, Dokras A. Increased risk of depressive disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility 2007;87(6):1369-76. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17397839

- Benson S, Hahn S, Tan S, Mann K, Janssen OE, Schedlowski M, et al. Prevalence and implications of anxiety in polycystic ovary syndrome: results of an internet-based survey in Germany. Human Reproduction 2009;24(6):1446-51. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19223290

- Jedel E, Waern M, Gustafson D, Landen M, Eriksson E, Holm G, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms in women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared with controls matched for body mass index. Human Reproduction 2010;25(2):450-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19933236

- Kerchner A, Lester W, Stuart SP, Dokras A. Risk of depression and other mental health disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a longitudinal study. Fertility and Sterility 2009;91(1):207-12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18249398

- Himelein MJ, Thatcher SS. Polycystic ovary syndrome and mental health: a review. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 2006;61(11):723-32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17044949

- Rasgon NL, Rao RC, Hwang S, Altshuler LL, Elman S, Zuckerbrow-Miller J, et al. Depression in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: clinical and biochemical correlates. Journal of Affective Disorders 2003;74(3):299-304. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12738050

- Dasgupta S, Reddy BM. Present status of understanding on the genetic etiology of polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine 2008;54:115-25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18480528

- The Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Consensus on infertility treatment related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction 2008;23:462-77. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18308833

- Padmanabhan V. Polycystic ovary syndrome “A riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma”. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2009;94:1883-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19494163

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Piperi C. Genetics of polycystic ovary syndrome: searching for the way out of the labyrinth. Human Reproduction Update 2005;11:631-43. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15994846

- Sam S. Obesity and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Obesity management. 2007;3(2):69-73. doi:10.1089/obe.2007.0019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2861983/

- Physical activity, body mass index, and ovulatory disorder infertility. Rich-Edwards JW, Spiegelman D, Garland M, Hertzmark E, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Wand H, Manson JE. Epidemiology. 2002 Mar; 13(2):184-90. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11880759/

- Polycystic ovary syndrome: syndrome XX ? Sam S, Dunaif A. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003 Oct; 14(8):365-70. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14516934/

- Prevalence and characteristics of the polycystic ovary syndrome in overweight and obese women. Alvarez-Blasco F, Botella-Carretero JI, San Millán JL, Escobar-Morreale HF. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Oct 23; 166(19):2081-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17060537/

- Should obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome receive treatment for infertility ? Balen AH, Dresner M, Scott EM, Drife JO. BMJ. 2006 Feb 25; 332(7539):434-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1382524/

- Lewis G, ed. Why mothers die 2000-2002 London: Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health, 2004.

- Improving reproductive performance in overweight/obese women with effective weight management. Norman RJ, Noakes M, Wu R, Davies MJ, Moran L, Wang JX. Hum Reprod Update. 2004 May-Jun; 10(3):267-80. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15140873/

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Fertility assessment and treatment for people with fertility problems. A clinical guideline. London: RCOG Press, 2004.

- Balen AH, Dresner M, Scott EM, Drife JO. Should obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome receive treatment for infertility?: Given the risks such women will face in pregnancy, they should lose weight first. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 2006;332(7539):434-435. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1382524/

- Balen AH. PCOS, obesity and reproductive function: RCOG Special Study Group on Obesity. 2007. London: RCOG Press.

- The degree of masculine differentiation of obesities: a factor determining predisposition to diabetes, atherosclerosis, gout, and uric calculous disease. VAGUE J. Am J Clin Nutr. 1956 Jan-Feb; 4(1):20-34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13282851/

- Body fat distribution in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Douchi T, Ijuin H, Nakamura S, Oki T, Yamamoto S, Nagata Y. Obstet Gynecol. 1995 Oct; 86(4 Pt 1):516-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7675372/

- Long-term testosterone administration increases visceral fat in female to male transsexuals. Elbers JM, Asscheman H, Seidell JC, Megens JA, Gooren LJ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997 Jul; 82(7):2044-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9215270/

- Ovarian and adrenal function in polycystic ovary syndrome. Rosenfield RL. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1999 Jun; 28(2):265-93. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10352919/

- Imprinting of female offspring with testosterone results in insulin resistance and changes in body fat distribution at adult age in rats. Nilsson C, Niklasson M, Eriksson E, Björntorp P, Holmäng A. J Clin Invest. 1998 Jan 1; 101(1):74-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC508542/

- Evidence for distinctive and intrinsic defects in insulin action in polycystic ovary syndrome. Dunaif A, Segal KR, Shelley DR, Green G, Dobrjansky A, Licholai T. Diabetes. 1992 Oct; 41(10):1257-66. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1397698/

- Ghrelin and measures of satiety are altered in polycystic ovary syndrome but not differentially affected by diet composition. Moran LJ, Noakes M, Clifton PM, Wittert GA, Tomlinson L, Galletly C, Luscombe ND, Norman RJ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Jul; 89(7):3337-44. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15240612/

- Moran LJ, Ko H, Misso M, Marsh K, Noakes M, Talbot M, Frearson M, Thondan M, Stepto N, Teede HJ. Dietary composition in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review to inform evidence-based guidelines. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2013; 113(4): 520-545. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212267212019259

- Zhuang J, Wang X, Xu L, Wu T, Kang D. Antidepressants for polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD008575. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008575.pub2. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008575.pub2/full

- Balen AH, Rutherford AJ. Managing anovulatory infertility and polycystic ovary syndrome. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 2007;335(7621):663-666. doi:10.1136/bmj.39335.462303.80. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1995495/

- What is polycystic ovary syndrome? Are national views important ? Balen A, Michelmore K. Hum Reprod. 2002 Sep; 17(9):2219-27. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12202405/

- Polycystic ovary syndrome: the spectrum of the disorder in 1741 patients. Balen AH, Conway GS, Kaltsas G, Techatrasak K, Manning PJ, West C, Jacobs HS. Hum Reprod. 1995 Aug; 10(8):2107-11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8567849/

- Detecting insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome: purposes and pitfalls. Legro RS, Castracane VD, Kauffman RP. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004 Feb; 59(2):141-54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14752302/

- Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group. Hum Reprod. 2004 Jan; 19(1):41-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14688154/

- Steroid secretion in polycystic ovarian disease after ovarian suppression by a long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist. Chang RJ, Laufer LR, Meldrum DR, DeFazio J, Lu JK, Vale WW, Rivier JE, Judd HL. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983 May; 56(5):897-903. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6403570/

- Characterization of groups of hyperandrogenic women with acanthosis nigricans, impaired glucose tolerance, and/or hyperinsulinemia. Dunaif A, Graf M, Mandeli J, Laumas V, Dobrjansky A. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987 Sep; 65(3):499-507. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3305551/

- Prevalence of insulin resistance in the polycystic ovary syndrome using the homeostasis model assessment. DeUgarte CM, Bartolucci AA, Azziz R. Fertil Steril. 2005 May; 83(5):1454-60. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15866584/

- Restored insulin sensitivity but persistently increased early insulin secretion after weight loss in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Holte J, Bergh T, Berne C, Wide L, Lithell H. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995 Sep; 80(9):2586-93. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7673399/

- The impact of obesity on hyperandrogenism and polycystic ovary syndrome in premenopausal women. Pasquali R, Casimirri F. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1993 Jul; 39(1):1-16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8348699/

- Improvement in endocrine and ovarian function during dietary treatment of obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Kiddy DS, Hamilton-Fairley D, Bush A, Short F, Anyaoku V, Reed MJ, Franks S. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1992 Jan; 36(1):105-11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1559293/

- Is polycystic ovary syndrome another risk factor for venous thromboembolism ? United States, 2003–2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 207(5):377.e1-377.e8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2012.08.007

- Ultrasound and menstrual history in predicting endometrial hyperplasia in polycystic ovary syndrome. Cheung AP. Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Aug; 98(2):325-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11506853/

- The role of obesity in the increased prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Gopal M, Duntley S, Uhles M, Attarian H. Sleep Med. 2002 Sep; 3(5):401-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14592171/

- Long-term health consequences of PCOS. Wild RA. Hum Reprod Update. 2002 May-Jun; 8(3):231-41. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12078834/

- Balen A, Rajkhowa R. Health consequences of polycystic ovary syndrome. In: Balen A, editor. Reproductive endocrinology for the MRCOG and beyond. 1st ed. London: RCOG press; 2003. pp. 99–107.

- Polycystic ovary syndrome and endometrial carcinoma. Hardiman P, Pillay OC, Atiomo W. Lancet. 2003 May 24; 361(9371):1810-2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12781553/

- Infertility, fertility drugs, and invasive ovarian cancer: a case-control study. Mosgaard BJ, Lidegaard O, Kjaer SK, Schou G, Andersen AN. Fertil Steril. 1997 Jun; 67(6):1005-12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9176436/

- Ovarian stimulation and borderline ovarian tumors: a case-control study. Mosgaard BJ, Lidegaard O, Kjaer SK, Schou G, Andersen AN. Fertil Steril. 1998 Dec; 70(6):1049-55. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9848294/

- Ovarian tumors in a cohort of infertile women. Rossing MA, Daling JR, Weiss NS, Moore DE, Self SG. N Engl J Med. 1994 Sep 22; 331(12):771-6. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199409223311204

- Mortality of women with polycystic ovary syndrome at long-term follow-up. Pierpoint T, McKeigue PM, Isaacs AJ, Wild SH, Jacobs HS. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998 Jul; 51(7):581-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9674665/

- Polycystic ovary syndrome and gynecological cancers: is there a link ? Gadducci A, Gargini A, Palla E, Fanucchi A, Genazzani AR. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2005 Apr; 20(4):200-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16019362/

- Familial associations in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Atiomo WU, El-Mahdi E, Hardiman P. Fertil Steril. 2003 Jul; 80(1):143-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12849816/

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Diagnosis Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pcos/diagnosis-treatment/diagnosis/dxc-20342160

- Goodman, N.F., Cobin, R.H., Futterweit, W., Glueck, J.S., Legro, R.S., Carmina, E. (2015). American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society disease state clinical review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome – part 1. Endocr Pract; (11):1291–300. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26509855

- Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Fertil Steril. 2004 Jan; 81(1):19-25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14711538/

- Zawadski JK, Dunaif A. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome; towards a rational approach. In: Dunaif A, Givens JR, Haseltine F, eds. Polycystic ovary syndrome Boston: Blackwell Scientific, 1992:377-84.

- The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Key TJ, Knochenhauer ES, Yildiz BO. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Jun; 89(6):2745-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15181052/

- Polycystic ovaries and associated clinical and biochemical features in young women. Michelmore KF, Balen AH, Dunger DB, Vessey MP. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1999 Dec; 51(6):779-86. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10619984/

- Polycystic ovaries and associated metabolic abnormalities in Indian subcontinent Asian women. Rodin DA, Bano G, Bland JM, Taylor K, Nussey SS. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1998 Jul; 49(1):91-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9797852/

- Clinical manifestations and insulin resistance (IR) in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) among South Asians and Caucasians: is there a difference ? Wijeyaratne CN, Balen AH, Barth JH, Belchetz PE. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2002 Sep; 57(3):343-50. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12201826/

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Treatment Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pcos/diagnosis-treatment/treatment/txc-20342167

- Modern use of clomiphene citrate in induction of ovulation. Kousta E, White DM, Franks S. Hum Reprod Update. 1997 Jul-Aug; 3(4):359-65. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9459281/

- Fertility: Assessment and Treatment for People with Fertility Problems. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (UK). London (UK): RCOG Press; 2004 Feb. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21089236/

- Low-dose gonadotrophin therapy for induction of ovulation in 100 women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hamilton-Fairley D, Kiddy D, Watson H, Sagle M, Franks S. Hum Reprod. 1991 Sep; 6(8):1095-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1806568/

- New approach to polycystic ovary syndrome and other forms of anovulatory infertility. Laven JS, Imani B, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BC. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002 Nov; 57(11):755-67. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12447098/

- Combined lifestyle modification and metformin in obese patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind multicentre study. Tang T, Glanville J, Hayden CJ, White D, Barth JH, Balen AH. Hum Reprod. 2006 Jan; 21(1):80-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16199429/

- Lashen H. Role of metformin in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;1(3):117-128. doi:10.1177/2042018810380215. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3475283/

- Boomsma, C.M., Fauser, B.C., & Macklon, N.S. (2008). Pregnancy complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine 26, 72–84. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18181085