Ovarian cyst

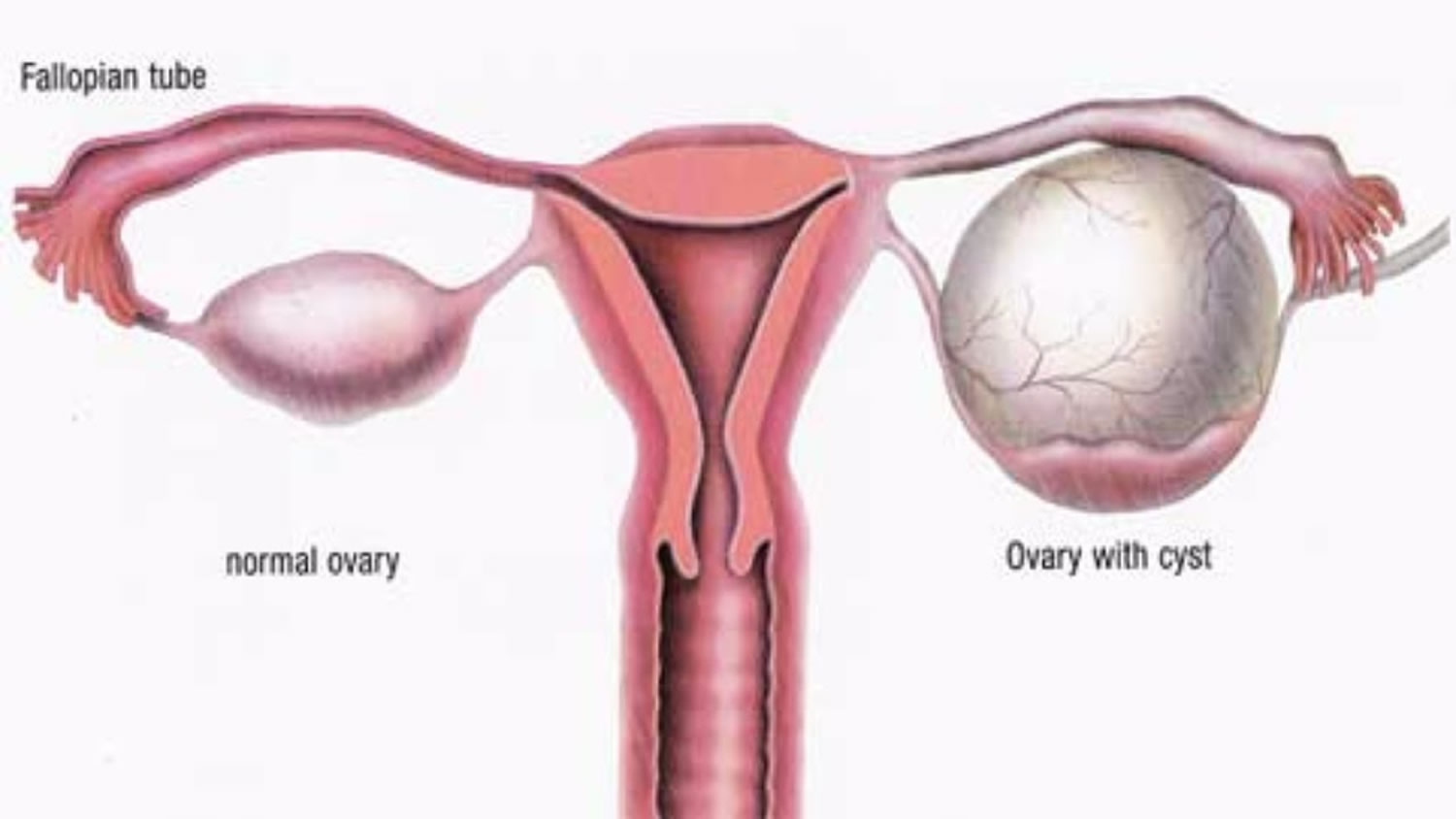

An ovarian cyst is a fluid-filled sac inside or on the surface of an ovary 1, 2, 3, 4. Most ovarian cysts occur as a normal part of the ovulation process (egg release) of your menstrual cycle, these are called functional ovarian cysts. Functional ovarian cysts usually go away within a few months without any treatment. If you develop an ovarian cyst, your doctor may want to check it again after your next menstrual cycle (period) to see if it has gotten smaller. Other types of ovarian cysts are much less common.

Ovarian cysts can occur at any age but are more common in reproductive years due to endogenous hormone production 5. An ovarian cyst can be more concerning in a female who isn’t ovulating (like a woman after menopause or a girl who hasn’t started her periods), and your doctor may want to do more tests. Your doctor may also order other tests if the ovarian cyst is large or if it does not go away in a few months. Even though most of ovarian cysts are benign (not cancer) and go away on their own without treatment, a small number of them could be cancer 4. Age is the most important independent risk factor, and post-menopausal women with any type of ovarian cyst should have proper follow-up and treatment due to a higher risk for cancer (malignancy) 6, 7. Sometimes the only way to know for sure if the ovarian cyst is cancer is to take it out with surgery. Ovarian cysts that appear to be benign (based on how they look on imaging tests) can be observed (with repeated physical exams and imaging tests), or removed with surgery.

Women have two ovaries — each about the size and shape of an almond — on each side of the uterus. Ovaries are a pair of small organs in the female reproductive system that contain and release an egg once a month in women of menstruating age. This is known as ovulation.

Many women have ovarian cysts at some time and usually form during ovulation. Ovulation happens when the ovary releases an egg each month. Many women with ovarian cysts don’t have symptoms. Most ovarian cysts present little or no discomfort and are harmless 8. The majority disappears without treatment within a few months 1.

Ovarian cysts are common in women with regular periods. In fact, most women make at least one follicle or corpus luteum cyst every month. You may not be aware that you have a cyst unless there is a problem that causes the cyst to grow or if multiple cysts form 9. Ovarian cysts — especially those that have ruptured or twisted— can cause serious symptoms 10, 11, 12. To protect your health, get regular pelvic exams and know the symptoms that can signal a potentially serious problem 12.

About 8% of premenopausal women develop large ovarian cysts that need treatment 13, 14.

Ovarian cysts are less common after menopause. Postmenopausal women with ovarian cysts are at higher risk for ovarian cancer.

At any age, see your doctor if you think you have an ovarian cyst. See your doctor also if you have symptoms such as bloating, needing to urinate more often, pelvic pressure or pain, or abnormal (unusual) vaginal bleeding. These can be signs of an ovarian cyst or other serious problem.

Most ovarian cysts occur naturally and are benign (not cancer) and go away on their own without needing any treatment 4. However, some ovarian cysts can be malignant (cancer), and large cysts greater than 5 cm can increase the risk of ovarian torsion or rupture 9, 15, 16. In these cases, surgical intervention may be indicated to avoid complications 1.

Ovarian cyst key points 17:

- Ovarian cysts are common. Most are variations of normal ovulatory function (functional ovarian cysts). Regardless of age, the likelihood of cancer is significantly less than the likelihood of a benign lesion.

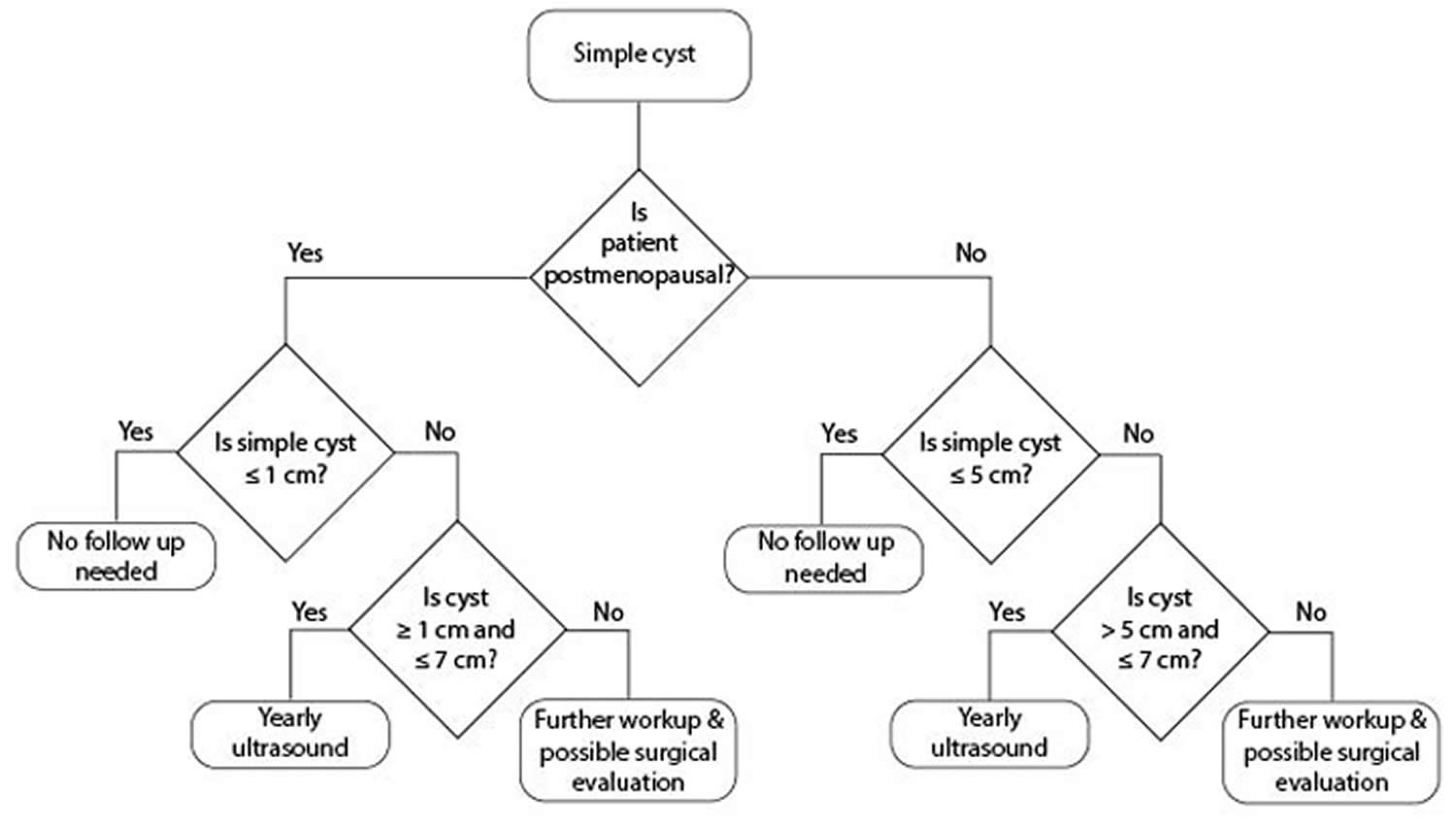

- Patients with ovarian cysts with benign characteristics (round or oval, anechoic, smooth, thin walls, no solid component, no internal flow, no or single thin septation, posterior acoustic enhancement) may be followed by your primary care doctor according to the algorithm in Figures 12 and 13 below, until resolution or stability of the ovarian cyst has been ascertained.

- Women with symptomatic ovarian cysts, those with cysts over 6 cm in diameter, or those with an uncertain, but likely benign diagnosis, can be managed by a general gynecologist.

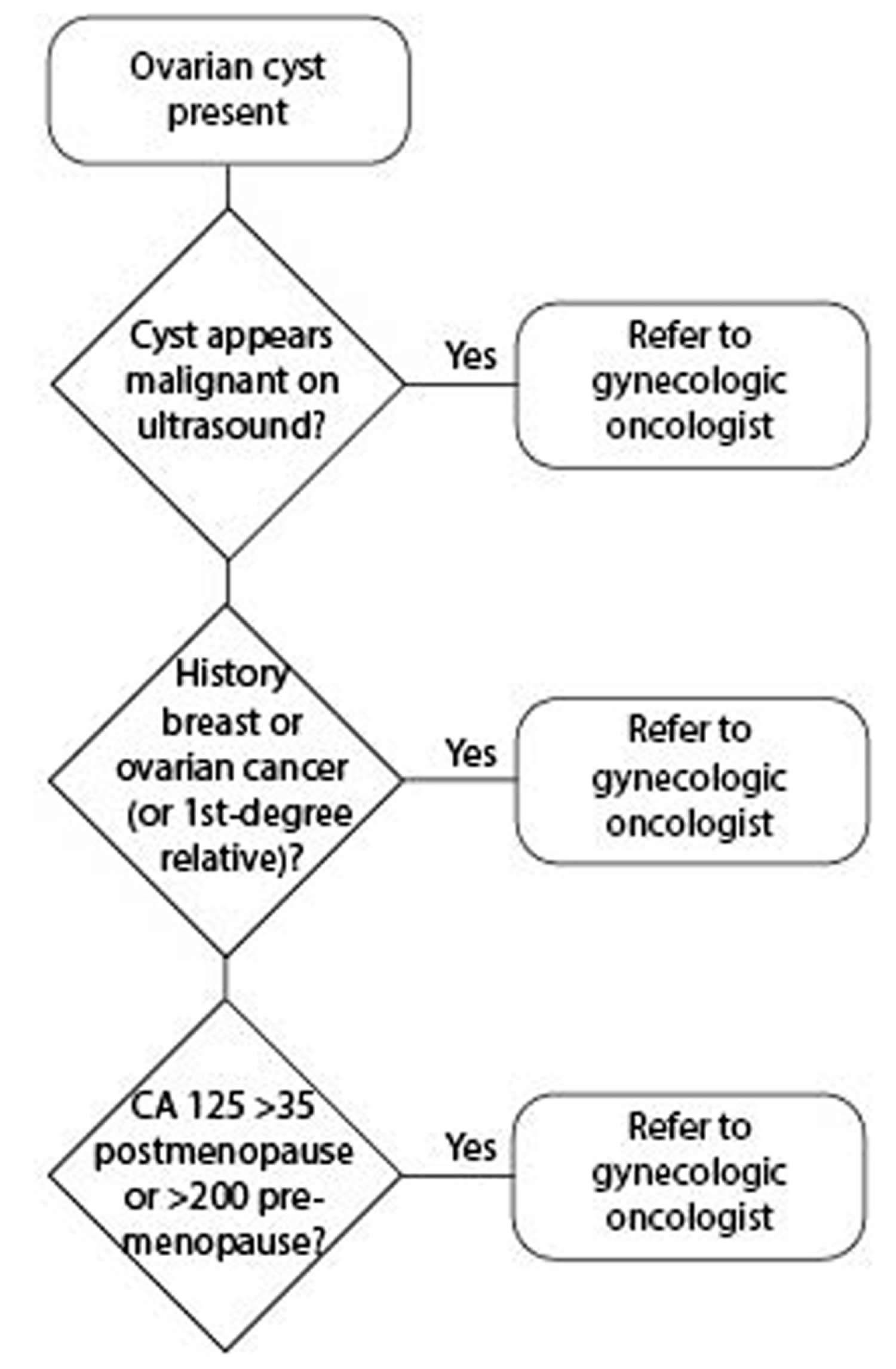

- Patients with ovarian cysts with frankly malignant characteristics (complex structure with thick >3mm septations, nodules or excrescences, especially if multiple or with internal blood flow, solid areas, or ascites) should be referred directly to a gynecologic oncologist. Referral should also be made to gynecologic oncology if the patient has an elevated CA 125 value, a personal or family history of breast or ovarian cancer in a first degree relative, or evidence of metastases.

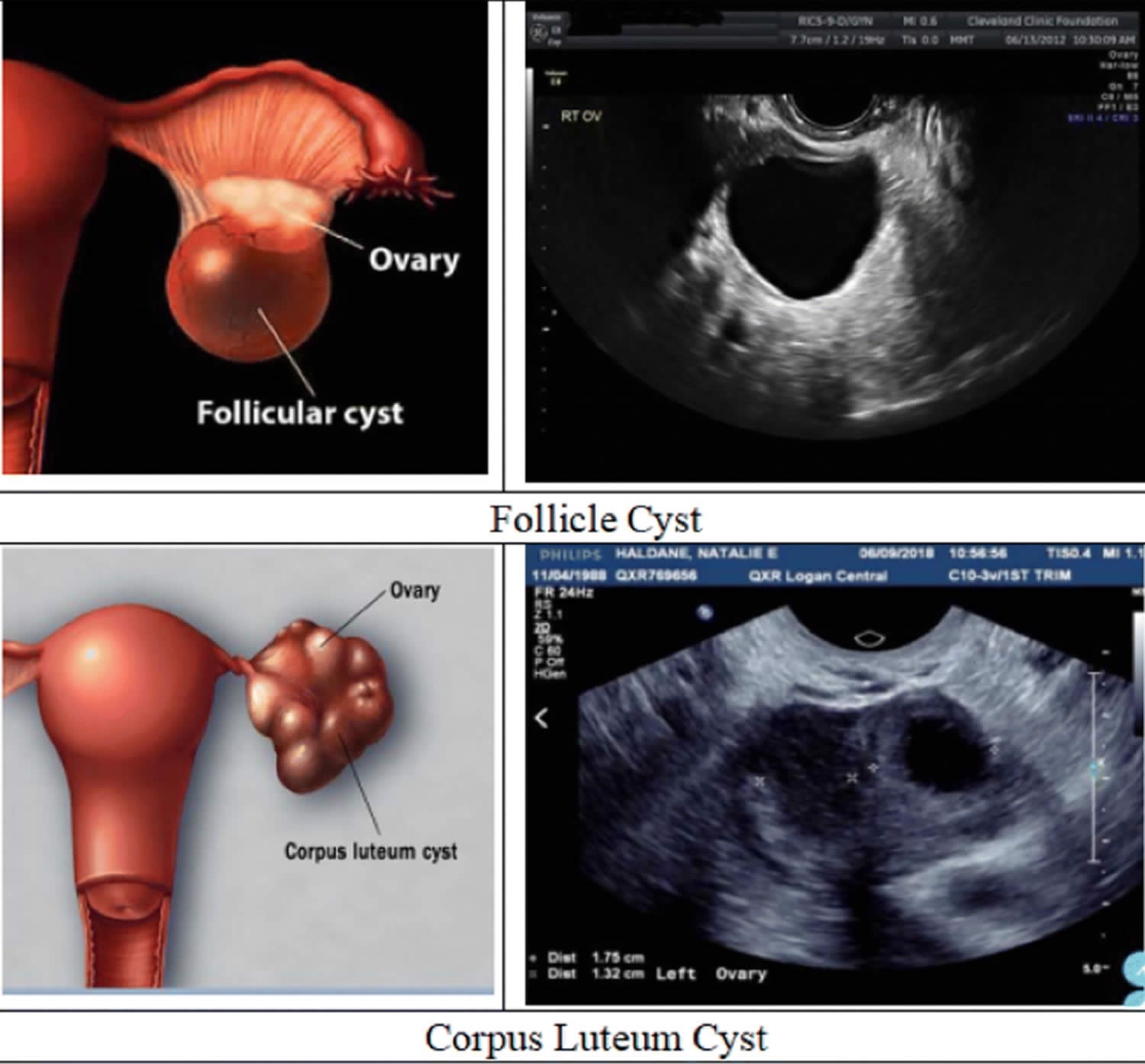

Figure 1. Ovarian cyst

Are ovarian cysts ever an emergency?

Yes, sometimes 8. If your doctor told you that you have an ovarian cyst and you have any of the following symptoms, get medical help right away:

- Pain with fever and vomiting

- Sudden, severe abdominal pain

- Faintness, dizziness, or weakness

- Rapid breathing

These symptoms could mean that your cyst has broken open, or ruptured. Sometimes, large, ruptured cysts can cause heavy bleeding 8.

Can ovarian cysts lead to cancer?

Yes, some ovarian cysts can become cancerous 8. But most ovarian cysts are not cancerous 8.The risk for ovarian cancer increases as you get older. Women who are past menopause with ovarian cysts have a higher risk for ovarian cancer. Talk to your doctor about your risk for ovarian cancer. Screening for ovarian cancer is not recommended for most women 18. This is because testing can lead to “false positives.” A false positive is a test result that says a woman has ovarian cancer when she does not.

Ovarian cancer risk factors

Generally, it’s not possible to say what causes ovarian cancer in an individual woman. However, some features are more common among women who have developed ovarian cancer. These features are called risk factors. Having certain risk factors increases a woman’s chance of developing ovarian cancer.

Having one or more risk factors for ovarian cancer doesn’t mean a woman will definitely develop ovarian cancer. In fact, many women with ovarian cancer have no obvious risk factors.

Factors that increase your risk of ovarian cancers:

- Getting older. The risk of developing ovarian cancer gets higher with age. Ovarian cancer is rare in women younger than 40. Most ovarian cancers develop after menopause. Half of all ovarian cancers are found in women 63 years of age or older.

- Being overweight or obese. Obesity has been linked to a higher risk of developing many cancers. The current information available for ovarian cancer risk and obesity is not clear. Obese women (those with a body mass index [BMI] of at least 30) may have a higher risk of developing ovarian cancer, but not necessarily the most aggressive types, such as high grade serous cancers. Obesity may also affect the overall survival of a woman with ovarian cancer.

- Having children later or never having a full-term pregnancy. Women who have their first full-term pregnancy after age 35 or who never carried a pregnancy to term have a higher risk of ovarian cancer.

- Using fertility treatment. Fertility treatment with in vitro fertilization (IVF) seems to increase the risk of the type of ovarian tumors known as “borderline” or “low malignant potential” (LMP tumors). Other studies, however, have not shown an increased risk of invasive ovarian cancer with fertility drugs. If you are taking fertility drugs, you should discuss the potential risks with your doctor.

- Taking hormone therapy after menopause. Women using estrogens after menopause have an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer. The risk seems to be higher in women taking estrogen alone (without progesterone) for many years (at least 5 or 10). The increased risk is less certain for women taking both estrogen and progesterone.

- Having a family history of ovarian cancer, breast cancer, or colorectal cancer. Ovarian cancer can run in families. Your ovarian cancer risk is increased if your mother, sister, or daughter has (or has had) ovarian cancer. The risk also gets higher the more relatives you have with ovarian cancer. Increased risk for ovarian cancer can also come from your father’s side. A family history of some other types of cancer such as colorectal and breast cancer is linked to an increased risk of ovarian cancer. This is because these cancers can be caused by an inherited mutation (change) in certain genes that cause a family cancer syndrome that increases the risk of ovarian cancer.

- Having a family cancer syndrome. Up to 25% of ovarian cancers are a part of family cancer syndromes resulting from inherited changes (mutations) in certain genes.

- Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. The hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome is caused by inherited mutations in the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, as well as possibly some other genes that have not yet been found. The hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome is linked to a high risk of breast cancer as well as ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancers. The risk of some other cancers, such as pancreatic cancer and prostate cancer, are also increased. Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are also responsible for most inherited ovarian cancers. Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are about 10 times more common in those who are Ashkenazi Jewish than those in the general U.S. population. The lifetime ovarian cancer risk for women with a BRCA1 mutation is estimated to be between 35% and 70%. This means that if 100 women had a BRCA1 mutation, between 35 and 70 of them would get ovarian cancer. For women with BRCA2 mutations the risk has been estimated to be between 10% and 30% by age 70. These mutations also increase the risks for primary peritoneal carcinoma and fallopian tube carcinoma. In comparison, the ovarian cancer lifetime risk for the women in the general population is less than 2%.

- PTEN tumor hamartoma syndrome. In this syndrome, also known as Cowden disease, people are primarily affected with thyroid problems, thyroid cancer, and breast cancer. Women also have an increased risk of endometrial and ovarian cancer. It is caused by inherited mutations in the PTEN gene.

- Lynch syndrome, also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). Women with this syndrome have a very high risk of colon cancer and also have an increased risk of developing cancer of the uterus (endometrial cancer) and ovarian cancer. Many different genes can cause hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). They include MLH1, MLH3, MSH2, MSH6, TGFBR2, PMS1, and PMS2. The lifetime risk of ovarian cancer in women with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (Lynch syndrome) is about 10%. Up to 1% of all ovarian epithelial cancers occur in women with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (Lynch syndrome).

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. People with this rare genetic syndrome develop polyps in the stomach and intestine while they are teenagers. They also have a high risk of cancer, particularly cancers of the digestive tract (esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon). Women with this syndrome have an increased risk of ovarian cancer, including both epithelial ovarian cancer and a type of stromal tumor called sex cord tumor with annular tubules (SCTAT). This syndrome is caused by mutations in the gene STK11.

- MUTYH-associated polyposis. People with this syndrome develop polyps in the colon and small intestine and have a high risk of colon cancer. They are also more likely to develop other cancers, including cancers of the ovary and bladder. This syndrome is caused by mutations in the gene MUTYH.

- Having had breast cancer. If you have had breast cancer, you might also have an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer. There are several reasons for this. Some of the reproductive risk factors for ovarian cancer may also affect breast cancer risk. The risk of ovarian cancer after breast cancer is highest in those women with a family history of breast cancer. A strong family history of breast cancer may be caused by an inherited mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes and hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome, which is linked to an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

- Smoking and alcohol use. Smoking doesn’t increase the risk of ovarian cancer overall, but it is linked to an increased risk for the mucinous type. Drinking alcohol is not linked to ovarian cancer risk.

Can ovarian cysts make it harder to get pregnant?

Typically, no 8. Most ovarian cysts do not affect your chances of getting pregnant 8. Sometimes, though, the illness causing the ovarian cyst can make it harder to get pregnant.

Two conditions that cause ovarian cysts and affect fertility are 8:

- Endometriosis, which happens when the lining of the uterus (womb) grows outside of the uterus. Cysts caused by endometriosis are called endometriomas.

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the leading causes of infertility (problems getting pregnant). Women with PCOS often have many small cysts on their ovaries.

If you need an operation to remove your cysts, your surgeon will aim to preserve your fertility whenever possible.

This may mean removing just the cyst and leaving the ovaries intact, or only removing 1 ovary.

In some cases, surgery to remove both your ovaries may be necessary, in which case you’ll no longer produce any eggs.

Make sure you talk to your surgeon about the potential effects on your fertility before your operation.

How do ovarian cysts affect pregnancy?

Ovarian cysts are common during pregnancy 8. Typically, these cysts are benign (not cancerous) and harmless 19. Ovarian cysts that continue to grow during pregnancy can rupture or twist or cause problems during childbirth. Your doctor will monitor any ovarian cyst found during pregnancy.

Can you prevent ovarian cysts?

No, you cannot prevent functional ovarian cysts if you are ovulating 8. If you get ovarian cysts often, your doctor may prescribe hormonal birth control to stop you from ovulating. This will help lower your risk of getting new cysts.

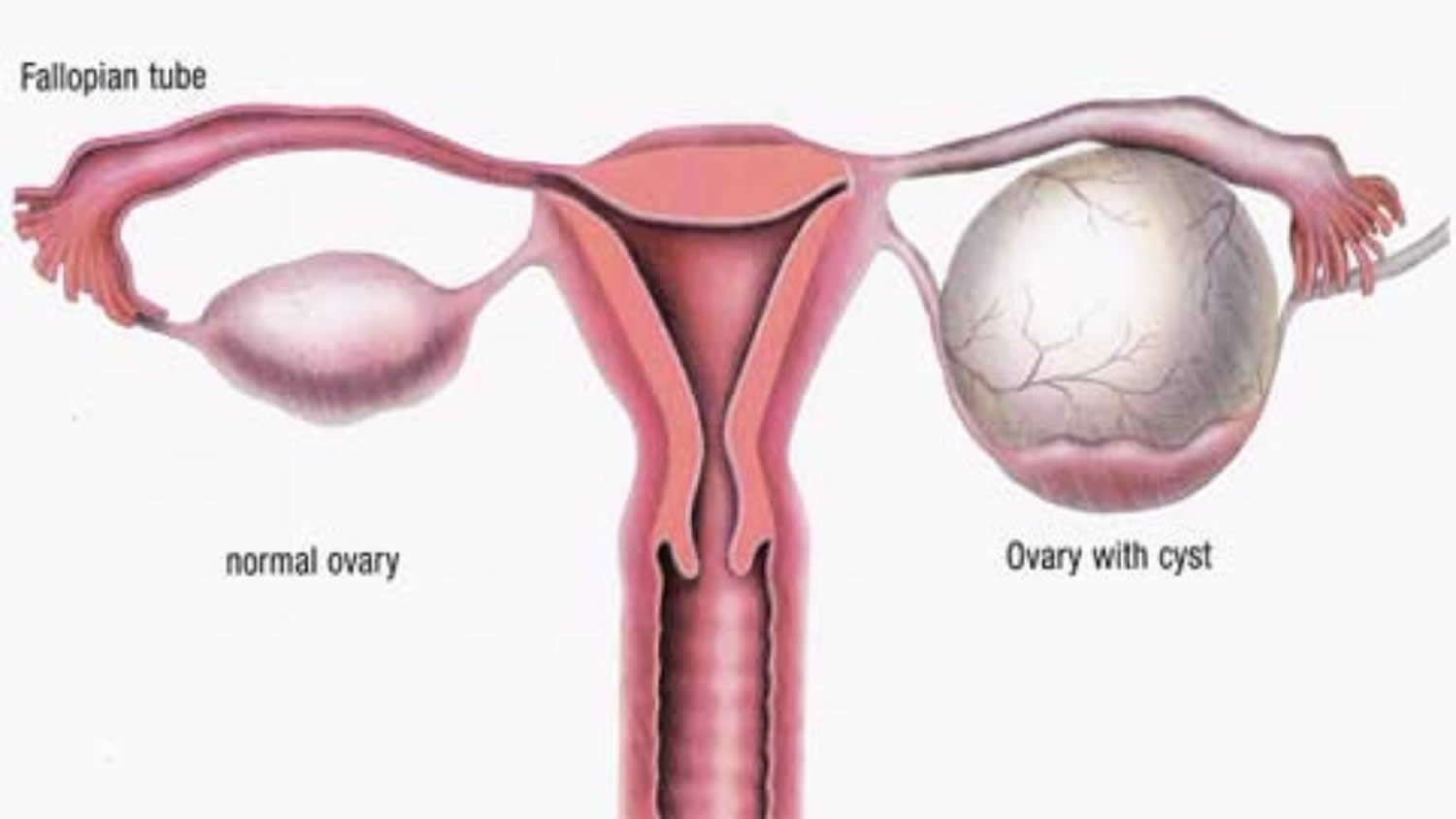

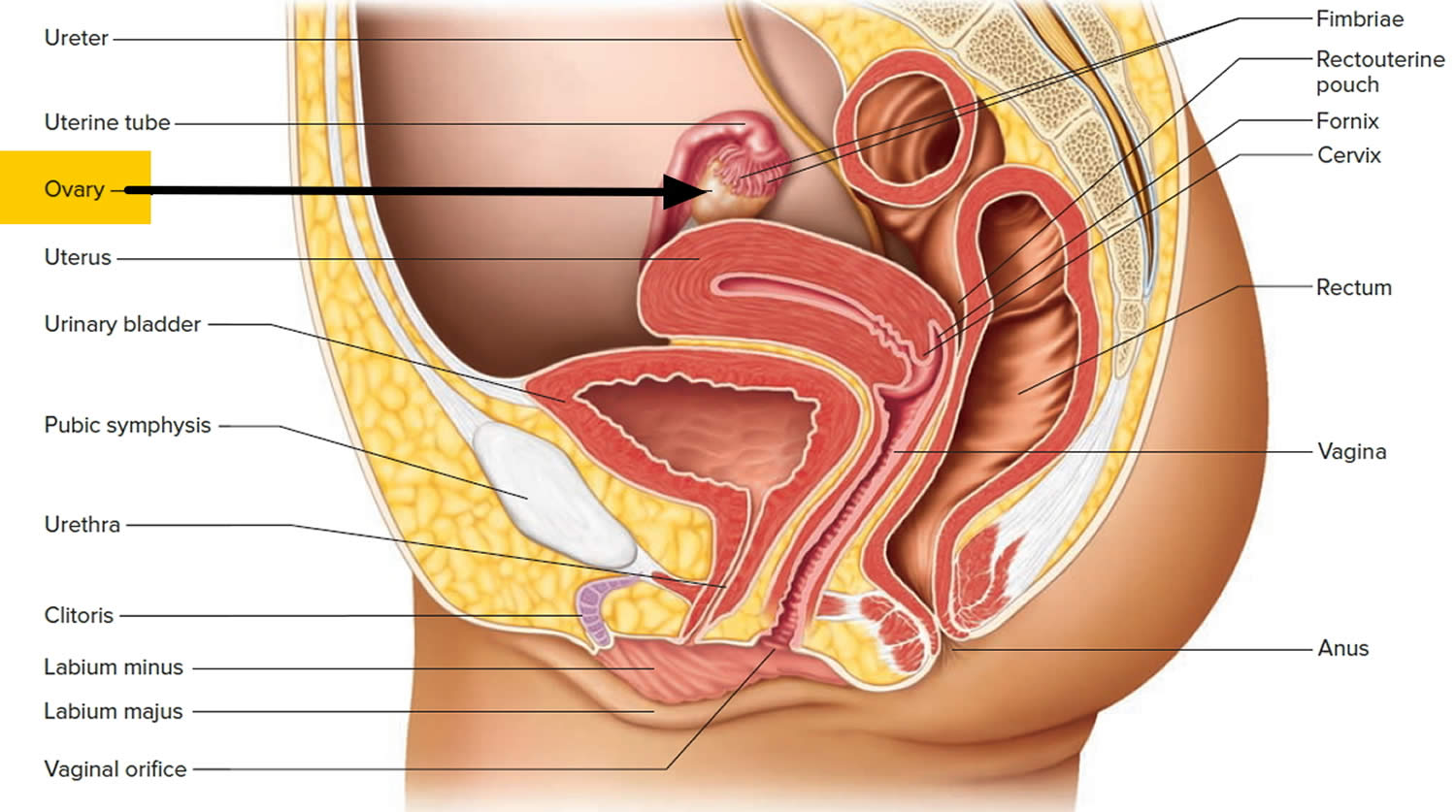

The female reproductive system

The ovaries are part of a woman’s reproductive system, which is made up of the:

- vulva

- vagina

- womb or uterus (which includes the cervix)

- fallopian tubes

- ovaries

There are 2 ovaries, one ovary is on each side of the uterus (womb). The ovaries produce an egg each month in women of childbearing age. In the middle of each menstrual cycle (mid way between periods), one of the ovaries releases an egg. It travels down the fallopian tube to the womb (uterus). The lining of the womb (uterus) gets thicker and thicker, ready to receive a fertilized egg. If the egg is not fertilised by sperm, the thickened lining of the womb is shed as a period. Then the whole cycle begins again.

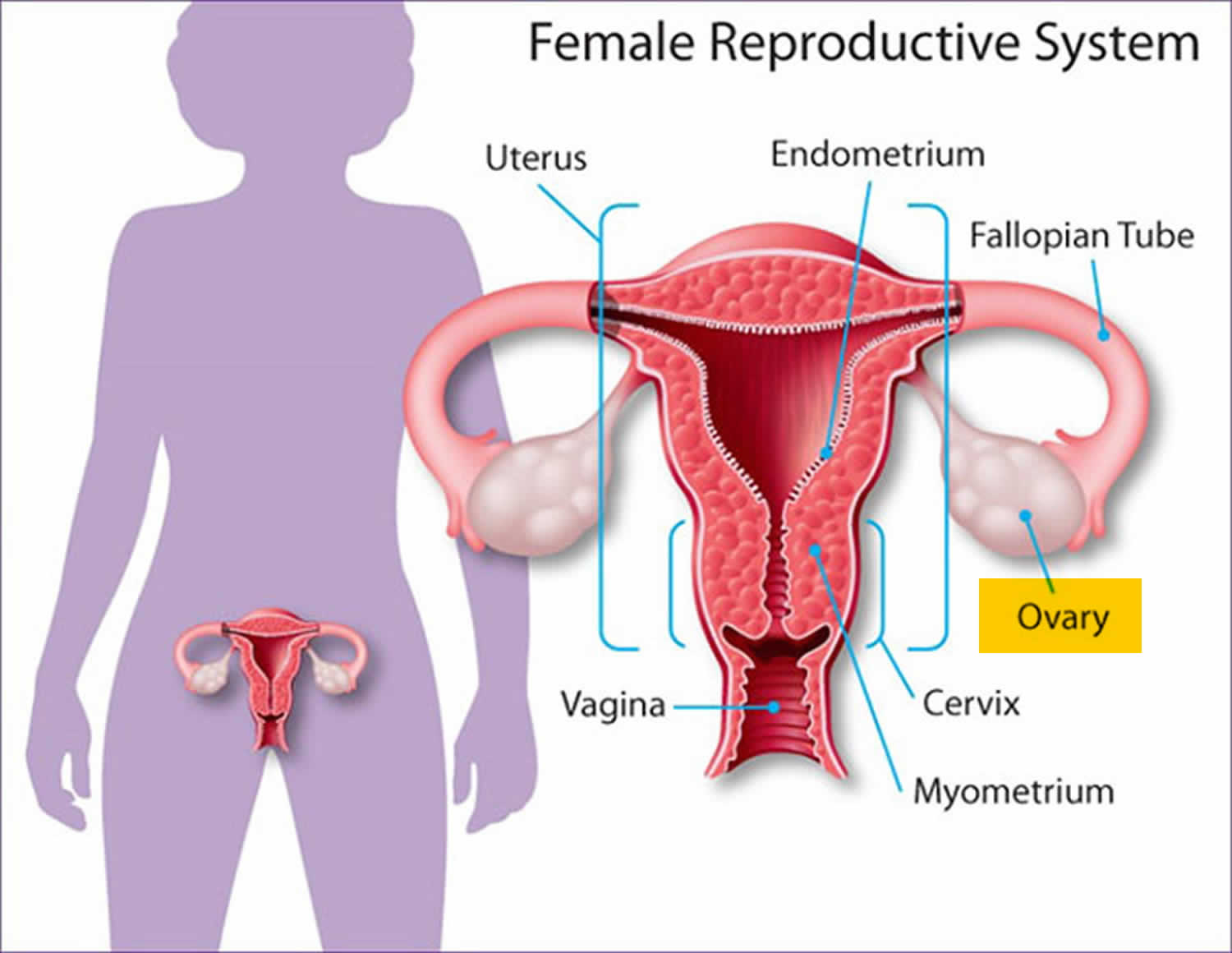

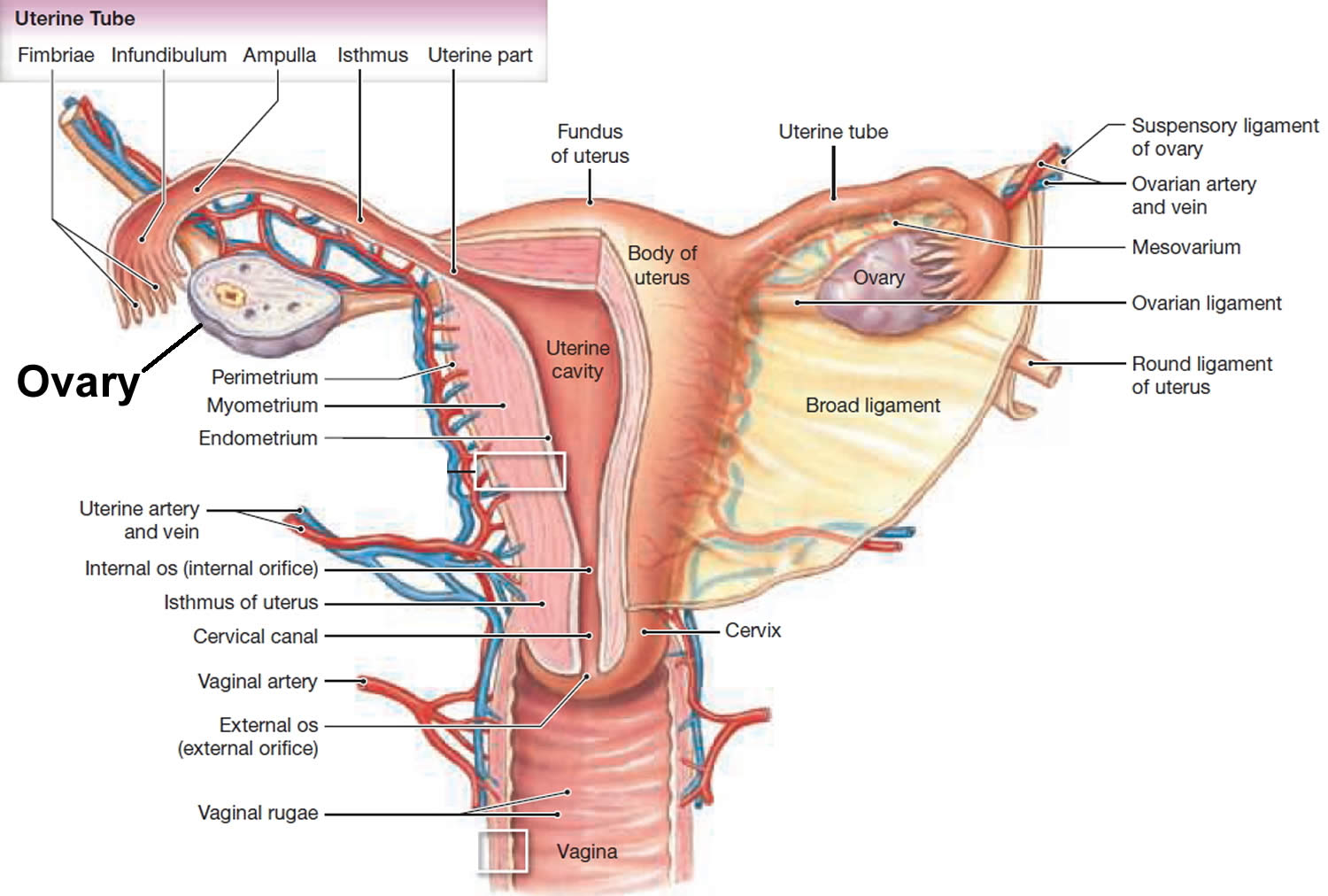

What are the ovaries?

Ovaries are reproductive glands found only in females (women). The ovaries produce eggs (ova) for reproduction. The ovaries hold the eggs which are released each month during child bearing age. The eggs travel from the ovaries through the fallopian tubes into the uterus where the fertilized egg settles in and develops into a fetus. The fallopian tubes connect the ovaries to the womb (also called the uterus). The ovaries are also the main source of the female sex hormones, estrogen and progesterone, which control your menstrual cycle (periods). As you get older and closer to menopause, the ovaries make less and less of these hormones and periods eventually stop. The ovarian hormones (estrogen and progesterone) also help to protect your heart and bones. And maintain brain and immune system health.

The ovaries produce a small amount of the male hormone testosterone. It is not completely clear what role testosterone has in women. But doctors think testosterone helps with muscle and bone strength. And it may have a role in a woman’s sex drive (libido).

When an egg is released it travels down the fallopian tube towards the womb (uterus). At this time, sperm from the male can pass into the fallopian tube where it may meet the egg and fertilize it. Fertilized eggs pass down the fallopian tube to the womb (uterus), which holds and protects the baby during pregnancy. The lining of the womb (uterus) is called the endometrium. It thickens during the menstrual cycle ready for pregnancy. If you don’t become pregnant you have a period which is when the lining sheds (also called a period or menstruation).

The cervix is the lower part of the womb. It is the opening into the vagina. During a period or menstruation blood passes from the womb through the cervix and then to the vagina. The vagina also opens and expands during sexual intercourse and stretches during childbirth to allow a baby to come out.

On the outside of the body is the vulva. It is made up of two pairs of lips. Between these is the opening of the vagina. Above the vagina is the urethra: a short tube that carries urine from the bladder to outside of the body and above the urethra is the clitoris: a very sensitive area that gives sexual pleasure.

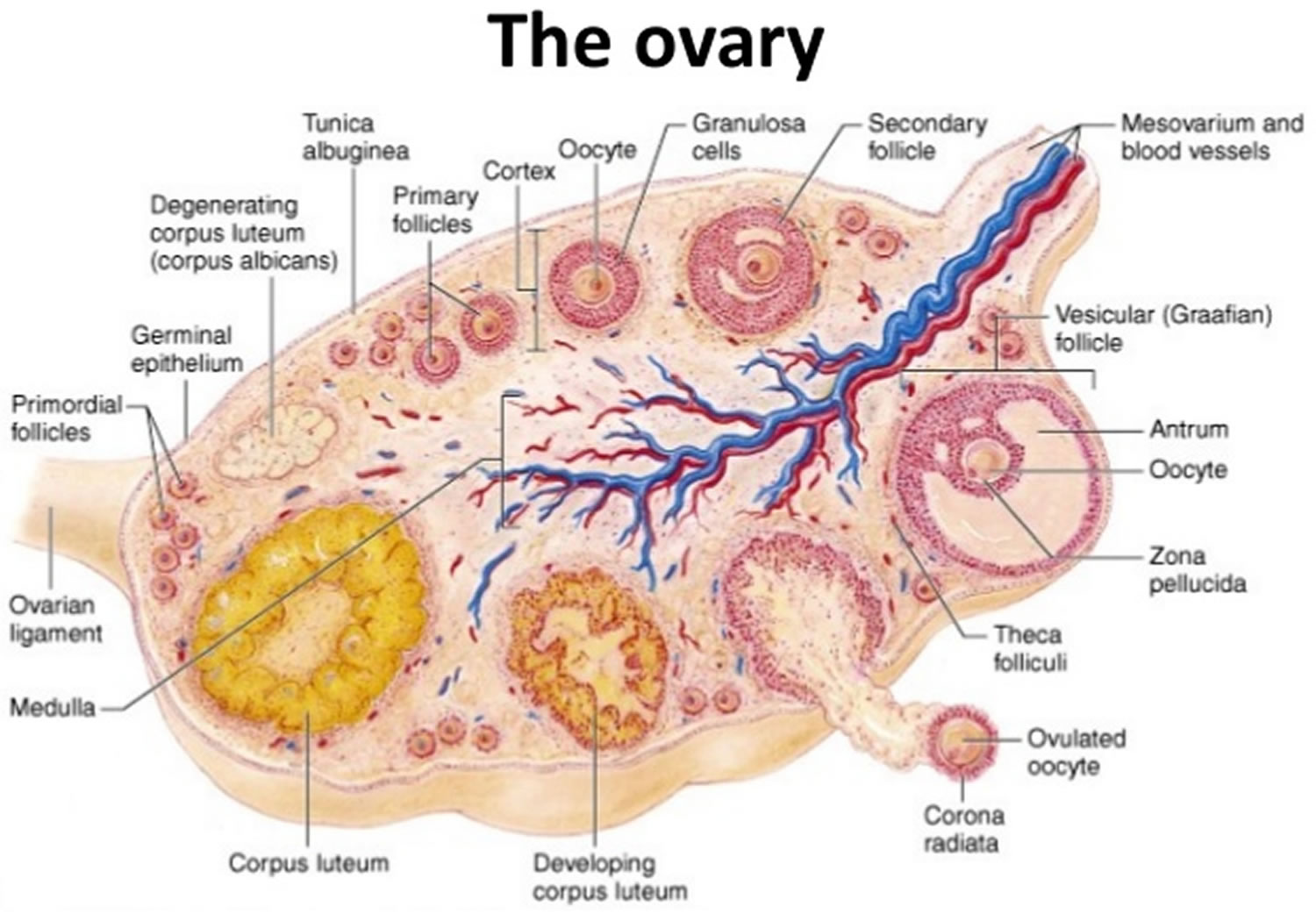

The ovaries are mainly made up of 3 kinds of cells. Each type of cell can develop into a different type of tumor:

- Epithelial tumors start from the cells that cover the outer surface of the ovary. Most ovarian tumors are epithelial cell tumors.

- Germ cell tumors start from the cells that produce the eggs (ova).

- Stromal tumors start from structural tissue cells that hold the ovary together and produce the female hormones estrogen and progesterone.

Some of these tumors are benign (non-cancerous) and never spread beyond the ovary. Malignant (cancerous) or borderline (low malignant potential) ovarian tumors can spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body and can be fatal.

Figure 2. Female reproductive system

Figure 3. The ovaries lie in shallow depressions in the lateral wall of the pelvic cavity

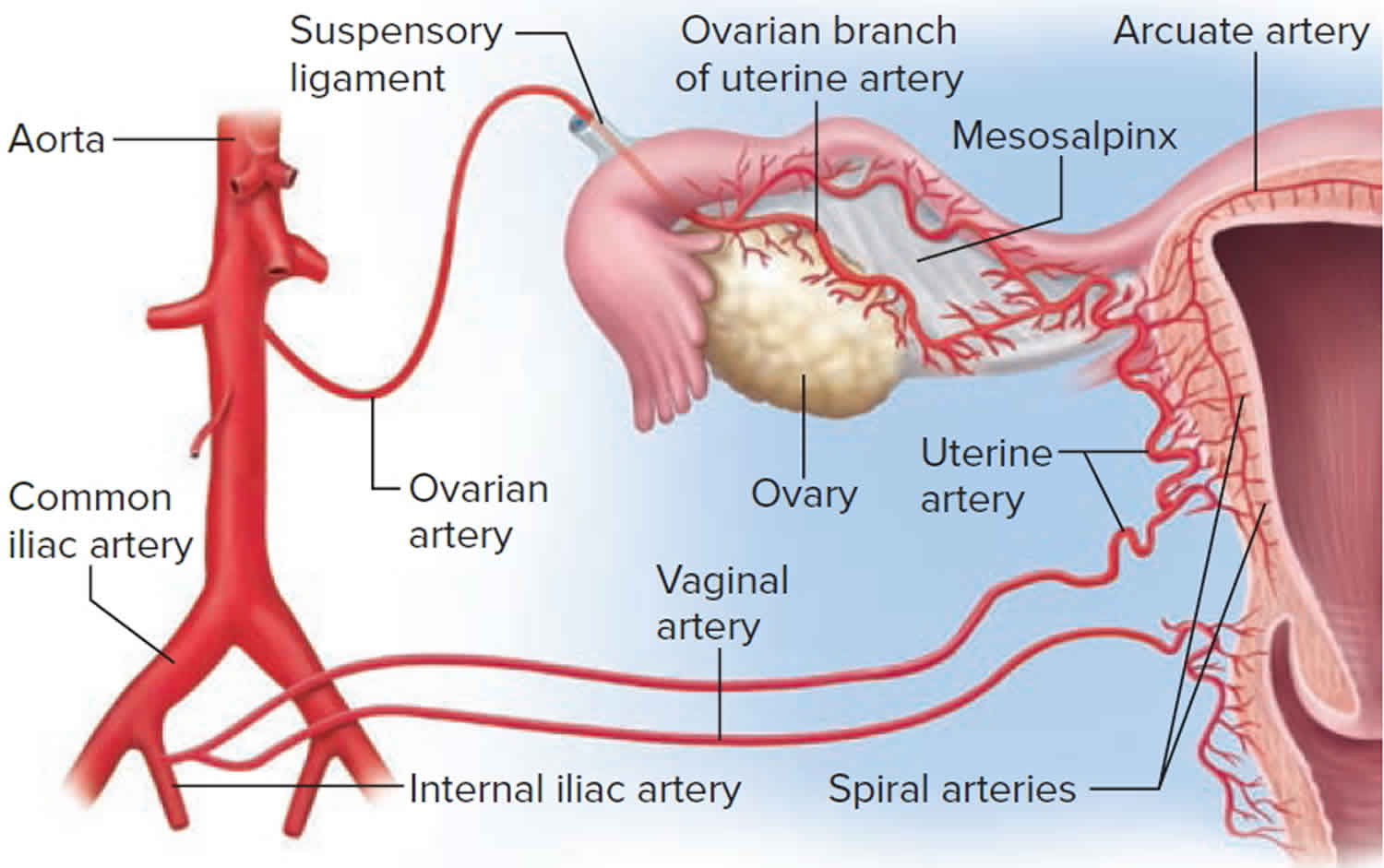

Figure 4. Ovary blood supply

Figure 5. Ovary anatomy

Types of ovarian cysts

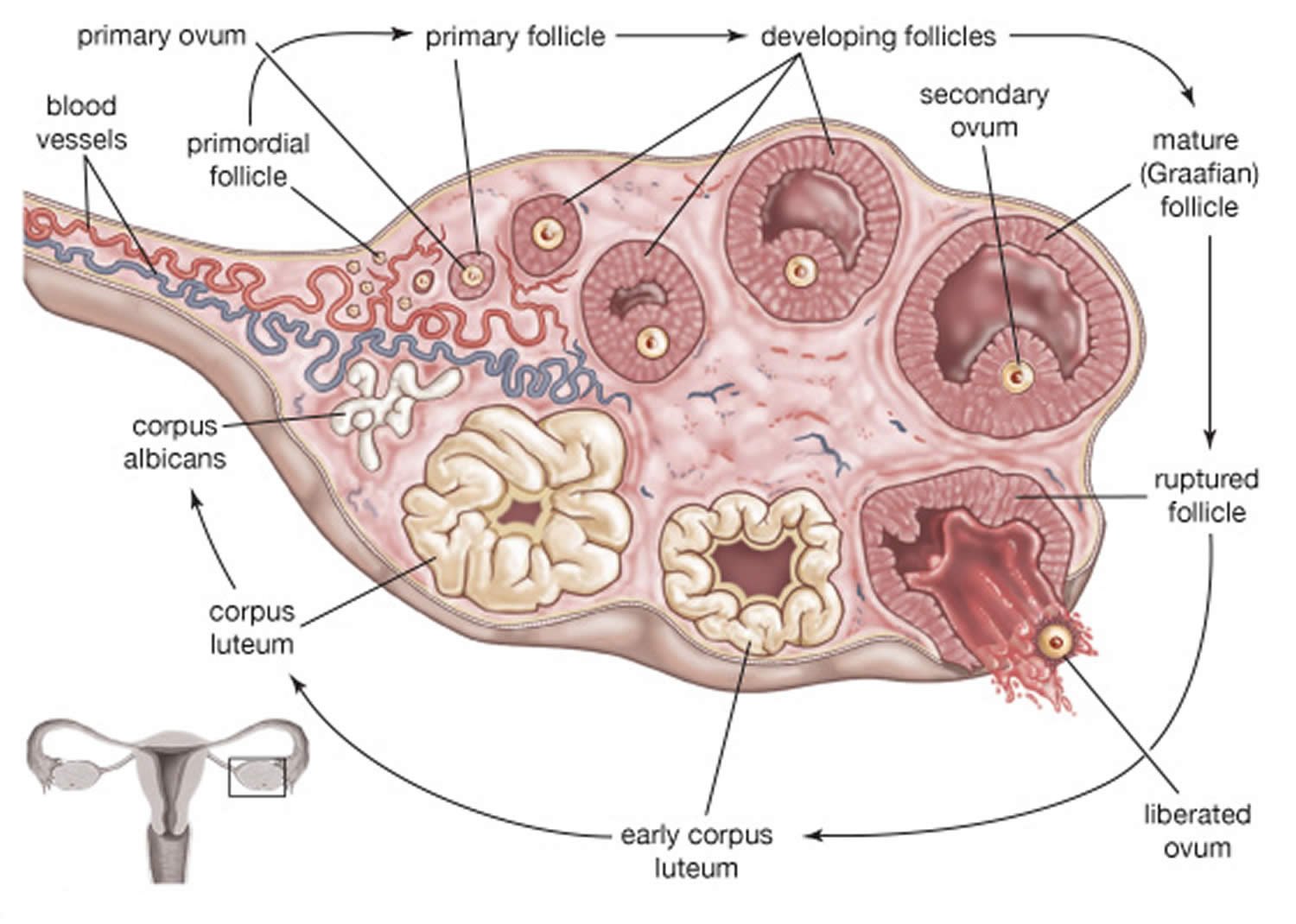

The most common types of ovarian cysts are called functional cysts, they form during the menstrual cycle and they happen if you have not been through the menopause (see Figure 4. Normal ovary) 20, 8. Functional ovarian cysts are usually benign (not cancerous) 8. Functional ovarian cysts are usually harmless, rarely cause pain, and often disappear on their own within two or three menstrual cycles.

The two most common types of functional cysts are 8:

- Follicle cysts. In a normal menstrual cycle, an ovary releases an egg each month. The egg grows inside a tiny sac called a follicle. When the egg matures, the follicle breaks open to release the egg. Around the midpoint of your menstrual cycle, an egg bursts out of its follicle and travels down the fallopian tube. Follicle cysts form when the follicle doesn’t break open to release the egg. This causes the follicle to continue growing into a cyst. Follicular cysts can appear smooth, thin-walled, and unilocular. Follicle cysts may form because of a lack of physiological release of the egg due to excessive follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulation or the absence of the usual luteinizing hormone (LH) surge at mid-cycle just before ovulation. These cysts continue to grow because of hormonal stimulation. Follicular cysts are usually larger than 2.5 cm in diameter. Follicle cysts often have no symptoms and go away in one to three months.

- Corpus luteum cysts. Once the follicle breaks open and releases the egg, the empty follicle sac shrinks into a mass of cells called corpus luteum. Corpus luteum makes hormones estrogen and progesterone to prepare for the next egg for the next menstrual cycle. Without pregnancy, the life span of the corpus luteum is 14 days. Corpus luteum cysts form if the sac doesn’t shrink. Instead, the sac reseals itself after the egg is released, and then fluid builds up inside. Most corpus luteum cysts go away after a few weeks. But, they can grow to almost four inches wide. They also may bleed or twist the ovary and cause pain. Some medicines used to cause ovulation can raise the risk of getting these cysts. Corpus luteal cysts can appear complex or simple, thick-walled, or contain internal debris. Corpus luteum cysts are always present during pregnancy and usually resolve by the end of the first trimester.

Both follicular and corpus luteal cysts can turn into hemorrhagic cysts. They are generally asymptomatic and spontaneously resolve without treatment 21.

Other types of benign ovarian cysts are less common:

- Theca lutein cysts. Theca lutein cysts are luteinized follicle cysts that form as a result of overstimulation in elevated human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels. Theca lutein cysts can occur in pregnant women, women with gestational trophoblastic disease, multiple gestation, and ovarian hyperstimulation.

- Endometriomas are caused by endometriosis. Endometriosis happens when the lining of the uterus (womb) grows outside of the uterus. Some of the lining of the uterus tissue can attach to your ovary and form a growth. Endometriomas (common in endometriosis) arise from ectopic growth of endometrial tissue and are often referred to as chocolate cysts because they contain dark, thick, gelatinous aged blood products. They appear as a complex mass on ultrasound and are described as having “ground glass” internal echoes. Endometriomas can be classified into two types. Type 1 endometrioma consists of small primary endometriomas that develop from surface endometrial implants. Type 2 endometrioma arises from functional cysts that have been invaded by ovarian endometriosis or type 1 endometriomas. Although the overall risk of malignant transformation is low, endometriomas increase this risk in women with endometriosis 22, 23, 24.

- Dermoids also called teratomas come from cells present from birth and do not usually cause symptoms. Dermoid cysts (teratomas) can contains different kinds of tissues that make up the body, such as hair, skin or teeth, because they form from embryonic cells. Although mostly benign, dermoid cysts (teratomas) can undergo a malignant transformation in 1 to 2% of cases 25, 26, 27.

- Cystadenomas develop on the surface of an ovary and might be filled with a watery or a mucous material. These tumors can grow very large even though they usually are benign.

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a disorder affecting 5 to 10% of women of reproductive age and is one of the primary causes of infertility. It is associated with diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) appears as enlarged ovaries with multiple small follicular cysts. The ovaries appear enlarged due to excess androgen hormones in the body, which cause the ovaries to form cysts and increase in size 28.

- Pregnancy ovarian cyst. Ovarian cysts in pregnancy are usually benign. Benign cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts) are the most common ovarian tumor during pregnancy, accounting for one-third of all benign ovarian tumors in pregnancy. The second most common benign ovarian cyst is a cystadenoma. In caring for pregnant women with ovarian cysts, a multidisciplinary approach and referral to a perinatologist and gynecologic oncologist is advised.

- Neonates and prepubertal children ovarian cyst. Ovarian cysts in the neonate are exceedingly rare. It is estimated that 5% of all abdominal masses in the first month of life are ovarian cysts. While there are no precise guidelines for the monitoring and management of neonatal ovarian cysts, it is generally agreed that cysts >2 cm are considered pathologic. The majority of neonatal ovarian cysts are benign and self-limiting. Ovarian malignancy becomes more common in the second decade of life than in the neonatal period. In one small study, approximately 33% of adnexal masses were malignant in children >8 years whereas 2.9% of adnexal masses were malignant in children <8 years 29.

Dermoid cysts and cystadenomas can become large, causing the ovary to move out of position. This increases the chance of painful twisting of your ovary, called ovarian torsion. Ovarian torsion may also result in decreasing or stopping blood flow to the ovary.

In some women, the ovaries make many small cysts. This is called polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). PCOS can cause problems with the ovaries and with getting pregnant.

Malignant (cancerous) ovarian cysts are rare 8. They are more common in older women. Cancerous cysts are ovarian cancer. For this reason, ovarian cysts should be checked by your doctor. Most ovarian cysts are not cancerous.

Ovarian cyst causes

The most common causes of ovarian cysts include 8:

- Hormonal problems. Functional cysts usually go away on their own without treatment. They may be caused by hormonal problems or by drugs used to help you ovulate.

- Endometriosis. Women with endometriosis can develop a type of ovarian cyst called an endometrioma. The endometriosis tissue may attach to the ovary and form a growth. These cysts can be painful during sex and during your period.

- Pregnancy. An ovarian cyst normally develops in early pregnancy to help support the pregnancy until the placenta forms. Sometimes, the cyst stays on the ovary until later in the pregnancy and may need to be removed.

- Severe pelvic infections. Infections can spread to the ovaries and fallopian tubes and cause cysts to form.

- A previous ovarian cyst. If you’ve had one, you’re likely to develop more.

Risk factors of developing ovarian cyst

Risk factors for ovarian cyst formation include:

- Infertility treatment. Patients treated with gonadotropins or other ovulation induction agents, for example clomiphene or letrozole (Femara), may develop ovarian cysts as part of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome 30

- Pregnancy. Sometimes, the follicle that forms when you ovulate stays on your ovary throughout pregnancy. In pregnancy, ovarian cysts may form in the second trimester when hCG levels peak 31. It can sometimes grow larger.

- Endometriosis. Some of the tissue can attach to your ovary and form a cyst.

- Severe pelvic infection. If the infection spreads to the ovaries, it can cause cysts.

- Previous ovarian cysts. If you’ve had one ovarian cyst, you’re likely to develop more.

- Tamoxifen therapy 5. Tamoxifen is widely used as hormonal therapy in both, pre- and postmenopausal women with breast cancer and effectively reduces the risk of recurrence and mortality 32, 33.

- Underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) 34

- Maternal gonadotropins. The transplacental effects of maternal gonadotropins may lead to the development of fetal ovarian cysts 35.

- Cigarette smoking 36.

- Tubal ligation. Functional ovarian cysts have been associated with tubal ligation sterilizations 37.

Ovarian cyst prevention

Oral contraceptives may prevent new functional cysts from forming 38, 39. However, oral contraceptives do not hasten the resolution of preexisting ovarian cysts. Some doctors will, nevertheless, prescribe oral contraceptives in an attempt to prevent new cysts from confusing the picture. Oral contraceptives are also protective against ovarian cancer 40.

In addition, getting regular pelvic exams ensure that changes in your ovaries are diagnosed as early as possible. Be alert to changes in your monthly cycle. Make a note of unusual menstrual symptoms, especially ones that go on for more than a few cycles. Talk to your doctor about changes that concern you.

Bilateral oophorectomy (surgical removal of both ovaries) protects against ovarian and breast cancer but is associated with an increase in the all-cause mortality rate 41. Current research suggests that removal of the fallopian tubes is protective against ovarian cancer 42.

Early-stage ovarian cancer rarely causes any symptoms or the symptoms can be very vague. Advanced-stage ovarian cancer may cause few and nonspecific symptoms that are often mistaken for more common benign conditions.

Signs and symptoms of ovarian cancer may include roughly 12 or more times a month of having:

- Abdominal bloating or swelling

- Pain or tenderness in your abdomen or the area between the hips (pelvis)

- No appetite or feeling full quickly after eating

- An urgent need to urinate or needing to urinate more often

These symptoms are also commonly caused by benign (non-cancerous) diseases and by cancers of other organs. When they are caused by ovarian cancer, they tend to be persistent and a change from normal − for example, they occur more often or are more severe. These symptoms are more likely to be caused by other conditions, and most of them occur just about as often in women who don’t have ovarian cancer. But if you have these symptoms more than 12 times a month, see your doctor so the problem can be found and treated if necessary.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that if you (especially if 50 or over) have the following symptoms on a persistent or frequent basis – particularly more than 12 times per month, your doctor should arrange tests – especially if you’re are over 50 43:

- persistent swollen tummy (abdomen) or bloating

- feeling full (early satiety) and/or loss of appetite

- pelvic or abdominal pain

- increased urinary urgency and/or frequency.

First tests:

- Measure serum cancer antigen 125 (CA125) in primary care in women with symptoms that suggest ovarian cancer

- If serum CA125 is 35 IU/ml or greater, arrange an ultrasound scan of the abdomen and pelvis.

- For any woman who has normal serum CA125 (less than 35 IU/ml), or CA125 of 35 IU/ml or greater but a normal ultrasound:

- assess her carefully for other clinical causes of her symptoms and investigate if appropriate

- if no other clinical cause is apparent, advise her to return to her doctor if her symptoms become more frequent and/or persistent.

Ovarian cyst symptoms

Most ovarian cysts are small and don’t cause symptoms. Many ovarian cysts are found during a routine pelvic exam or imaging test done for another reason. Some ovarian cysts may cause a dull or sharp ache in the abdomen and pain during certain activities. Larger ovarian cysts may cause twisting of the ovary. This twisting may cause pain on one side that comes and goes or can start suddenly. Cysts that bleed or burst also may cause sudden, severe pain.

If an ovarian cyst does cause symptoms, you may have pressure, bloating, swelling, or pain in the lower abdomen on the side of the cyst 8. This pain may be sharp or dull and may come and go 8.

If an ovarian cyst ruptures, it can cause sudden, severe pain 8.

If an ovarian cyst causes twisting of an ovary, you may have pain along with nausea and vomiting 8.

Less common symptoms include:

- Pelvic pain that may come and go. You may feel a dull ache or a sharp pain in the area below your bellybutton toward one side.

- Dull ache in the lower back and thighs

- Fullness, pressure or heaviness in your belly (abdomen)

- Feeling very full after only eating a little

- Bloating and a swollen tummy

- Problems emptying your bladder or bowel completely

- Pain during sex

- Unexplained weight gain

- Pain during your period

- Unusual (not normal) vaginal bleeding

- Heavy periods, irregular periods or lighter periods than normal

- Breast tenderness

- Needing to urinate more often

- Difficulty getting pregnant – although fertility is usually unaffected by ovarian cysts.

Get immediate medical help if you have:

- Sudden, severe abdominal or pelvic pain.

- Pain with fever or vomiting.

- Signs of shock. These include cold, clammy skin; rapid breathing; and lightheadedness or weakness.

Ovarian cyst complications

Some women develop less common types of ovarian cysts that a doctor finds during a pelvic exam. Cystic ovarian masses that develop after menopause might be cancerous (malignant). That’s why it’s important to have regular pelvic exams.

Infrequent complications associated with ovarian cysts include:

- Ovarian torsion. Cysts that enlarge can cause the ovary to move, increasing the chance of painful twisting of your ovary (ovarian torsion). Symptoms can include an abrupt onset of severe pelvic pain, nausea and vomiting. Ovarian torsion can also decrease or stop blood flow to the ovaries.

- Ovarian cyst rupture. All ovarian cyst types can potentially rupture, spilling fluid into the pelvis, which is often painful. An ovarian cyst that ruptures can cause severe pain and internal bleeding. If the contents are from a dermoid or abscess, surgical lavage may be indicated. The larger the cyst, the greater the risk of rupture. Vigorous activity that affects the pelvis, such as vaginal intercourse, also increases the risk.

- Bleeding into the ovarian cyst. In the case of hemorrhagic ovarian cysts, the management of hemorrhage depends on the hemodynamic stability of the patient, but is most often expectantly managed.

The fifth most common gynecological emergency is ovarian torsion, defined as the complete or partial twisting of the ovarian vessels resulting in obstruction of blood flow to the ovary. The diagnosis is made clinically with the assistance of a history and physical examination, bloodwork, and imaging and is confirmed by diagnostic laparoscopy. The latest evidence supports a conservative approach during diagnostic laparoscopy, and detorsion of the ovary with or without cystectomy is recommended to preserve fertility.

Ovarian cysts can also rupture or hemorrhage, with most of these being physiological. Most cases are uncomplicated with mild to moderate symptoms, and those with stable vital signs can be managed expectantly. Occasionally, this can be complicated by significant blood loss resulting in hemodynamic instability requiring admission to the hospital, surgical evacuation, and blood transfusion 9.

Ruptured ovarian cyst

Ruptured ovarian cysts and hemorrhagic ovarian cysts are the most common causes of acute pelvic pain in an afebrile, premenopausal woman presenting to the emergency room 44. Rebound tenderness from the pain is possible and the bleeding from a cyst can rarely be severe enough to cause shock 45. It is a common cause of physiological pelvic intraperitoneal fluid.

Ovarian cysts may rupture during pregnancy (if a very early pregnancy, this may cause diagnostic confusion with ectopic pregnancy).

Although rupture of an ovarian follicle is a physiologic event (mittelschmerz (German for ‘middle pain’)), the rupture of an ovarian cyst (>3 cm) may cause more dramatic clinical symptoms.

The sonographic appearance depends on whether a simple or hemorrhagic ovarian cyst ruptures, and whether the cyst has completely collapsed. The most important differential consideration is a ruptured ectopic pregnancy 46.

Ruptured ovarian cyst symptoms

Ruptured ovarian cysts and hemorrhagic ovarian cysts are the most common causes of acute pelvic pain in an afebrile, premenopausal woman presenting to the emergency room 44. The pain from a ruptured ovarian cyst may come from stretching the capsule of the ovary, torquing of the ovarian pedicle, or leakage of cyst contents (serous fluid/blood) which can cause peritoneal irritation 45.

Ruptured ovarian cyst treatment

Ruptured ovarian cyst is treated conservatively in a premenopausal woman unless evidence of hypovolemic shock (tachycardia and postural drop in blood pressure) 46.

A ruptured hemorrhagic cyst in a perimenopausal woman should be viewed more suspiciously and followed up appropriately 46. A hemorrhagic cyst or ruptured cyst in a postmenopausal woman deserves surgical evaluation 46.

Ovarian torsion

Ovarian torsion is caused by twisting of the ligaments that support the ovary, cutting off the blood flow to the ovary and represents a true surgical emergency that can lead to necrosis, loss of ovary, and infertility if not identified early 47, 48. Ovarian torsion is characterized by a twisted ovary with or without the involvement of the fallopian tube 49. When fallopian tube also twists with the ovary it is known as adnexal torsion 50. The diagnosis of ovarian torsion can only be confirmed by surgery 49. Furthermore, the female reproductive function may be negatively affected by delayed treatment because of uncertainty in the preoperative diagnosis.

The ovary has dual blood supply from the ovarian arteries and uterine arteries. The ovary is supported by multiple structures in the pelvis. One ligament it is suspended by is the infundibulopelvic ligament, also called the suspensory ligament of the ovary, which connects the ovary to the pelvic sidewall. This ligament also contains the main ovarian vessels. The ovary is also connected to the uterus by the utero-ovarian ligament 51. Twisting of these ligaments can lead to venous congestion, edema, compression of arteries, and, eventually, loss of blood supply to the ovary. This can cause a constellation of symptoms, including severe pain when blood supply is compromised.

The main risk factor for ovarian torsion is an ovarian mass that is 5 cm in diameter or larger 47. The mass increases the chance that the ovary could rotate on the axis of the two ligaments holding it in suspension. This torsion impedes venous outflow and eventually, arterial inflow.

In a study of torsions confirmed by surgery, 46% were associated with tumors, and 48% were associated with cysts. Of these masses, 89% were benign, and 80% of patients were under age 50. Therefore, reproductive-age females are at greatest risk of torsion 52. However, torsion can still occur in normal ovaries, especially in children and adolescents. Pregnancy, as well as patients undergoing fertility treatments, are high risk due to enlarged follicles on the ovary 51.

The clinical symptoms of ovarian torsion are variable and nonspecific 49. Classic clinical symptoms of ovarian torsion include the sudden onset of severe pelvic pain and a palpable adnexal mass (a lump in tissue near the uterus, usually in the ovary or fallopian tube) 53. Moreover, nausea, vomiting, and fever are present in some cases 54. Reproductive age is the peak period of incidence of ovarian torsion, and approximately 70% of cases occur during this period 55. It is estimated that 12% to 18% of patients with ovarian torsion are pregnant 56, 57, 58. However, whether pregnancy is a risk factor of ovarian torsion is still controversial 59, 60.

Physical exam in the patient is variable. The patient may have abdominal tenderness focally in the lower abdomen, pelvic area, diffusely, or not at all. Up to one-third of patients were found to have no abdominal tenderness. There could also be an abdominal mass. If the patient has guarding, rigidity, or rebound, there may already be necrosis of the ovary. Every patient should also have a pelvic exam to better evaluate for masses, discharge, and cervical motion tenderness.

Pelvic ultrasonic examination is the most frequently performed preoperative examination, but ultrasonic findings are nonspecific, despite the ultrasonic features of ovarian torsion being well-characterized 48, 61, 62.

Ovarian torsion is the fifth most common gynecological emergency requiring surgery, with an estimated prevalence of about 2.7% to 3% 63. Urgent surgery is required to prevent ovarian necrosis. Most ovaries are not salvageable, in which case a salpingo-oophorectomy is required. If not removed, the necrotic ovary can become infected and cause an abscess or peritonitis. In the case of a non-infarcted adnexa, surgical untwisting can be performed. Mortality resulting from ovarian torsion is rare. Spontaneous detorsion has also been reported.

Ovarian torsion symptoms

The clinical symptoms of ovarian torsion are variable and nonspecific 49. Most patients will present with lower abdominal pain or pelvic pain. Pain can be sharp, dull, constant, or intermittent. Pain may radiate to the abdomen, back, or flank 64. One study showed that post-menopausal women commonly presented with dull, constant pain when compared to premenopausal, who more commonly had sharp stabbing pain. Symptoms may or may not be intermittent if the ovary is torsing and detorsing.

The patient may also have associated nausea and vomiting. In one study of children and adolescents with lower abdominal pain, vomiting was found to be an independent risk factor for ovarian torsion 65. The patient may or may not already have a known ovarian mass, which predisposes them to torsion.

Fever may be present if the ovary is already necrotic. The patient could also have abnormal vaginal bleeding, or discharge if torsion involves a tubo-ovarian abscess. Infants with ovarian torsion may present with feeding intolerance or inconsolability.

Ovarian torsion treatment

Ovarian torsion requires urgent surgery to prevent ovarian necrosis 47. The treatment of ovarian torsion is surgical detorsion, preferably by a gynecologist 47.

In reproductive age females, salvage of the ovary should be attempted, and the surgeon must evaluate the ovary for viability 47. Most often, the approach to surgery should be laparoscopic and involves direct visualization of a twisted ovary. The evaluation of viability is mostly by visualization. A dark, enlarged ovary with hemorrhagic lesions may have compromised blood flow but is often salvageable 57.

After detorsion, ovaries were found to be functional in greater than 90% of patients who underwent detorsion 47. This was assessed by the appearance of the adnexa on ultrasound, including follicular development on the ovaries 66. Therefore, surgery with sparing of the ovary is the management of choice 47. Rarely, if the ovary appears necrotic and gelatinous beyond possible salvage, the surgeon may choose to perform a salpingo-oophorectomy 47. The surgeon may also perform cystectomy if a benign ovarian cyst is present. If the ovarian cyst appears to be malignant, or if the woman is post-menopausal, salpingo-oophorectomy is the preferred management 47.

Ovarian torsion prognosis

Ovarian torsion is not usually life-threatening, but it is organ threatening. In premenopausal women, surgery with sparing of the ovary is now the preferred treatment, and the majority of women had normal-appearing ovary on ultrasound after surgery 67. Ovarian salvage is increased in patients with less time from the onset of symptoms to surgical intervention. In postmenopausal women, salpingo-oophorectomy is done to prevent reoccurrence. This approach is also used in women with a mass suspicious for malignancy. The majority of ovarian masses are benign. Some case reports show less than 2% of torsions involving a malignant lesion. However, the chances of a malignant lesion involved in ovarian torsion are increased in the postmenopausal women 51.

The main complication of ovarian torsion is the inability to salvage the ovary and the need for salpingo-oophorectomy. This may affect fertility in a woman of childbearing age. Other complications of ovarian torsion include abnormal pelvic anatomy that may contribute to infertility, such as adhesions, or atrophied ovaries 68. There may be complications from the surgery itself, such as infection or venous thromboembolism. The risk of post-operative infection is increased when necrotic tissue is already present 69.

Ovarian cyst diagnosis

If you have symptoms of ovarian cysts, talk to your doctor. Your doctor may do a pelvic exam to feel for swelling of a cyst on your ovary.

A cyst on your ovary can also be found during a routine pelvic exam. Depending on its size and whether it’s fluid filled, solid or mixed, your doctor likely will recommend tests to determine its type and whether you need treatment.

Tests include:

- Pelvic ultrasound. This test uses sound waves to create images of the body. With ultrasound, your doctor can see the cyst’s: Shape / Size / Location / Mass (whether it is fluid-filled, solid, or mixed). If a cyst is identified during the ultrasound scan, you may need to have this monitored with a repeat ultrasound scan in a few weeks, or your doctor may refer you to a doctor who specializes in female reproductive health (obstetrician–gynecologist).

- Pregnancy test to rule out pregnancy. A positive test might suggest that you have a corpus luteum cyst.

- Hormone level tests to see if there are hormone-related problems

- Tumor marker tests. If you are past menopause, your doctor may give you a test to measure the amount of cancer-antigen 125 (CA-125) in your blood. The amount of CA-125 is higher with ovarian cancer. If your ovarian cyst is partially solid and you’re at high risk of ovarian cancer, your doctor might order this test. In premenopausal women, many other illnesses or diseases besides cancer can cause higher levels of CA-125. Elevated CA 125 levels can also occur in noncancerous conditions, such as endometriosis, uterine fibroids and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

- Laparoscopy. Using a laparoscope — a slim, lighted instrument inserted into your abdomen through a small incision — your doctor can see your ovaries and remove the ovarian cyst. This is a surgical procedure that requires anesthesia.

Sometimes, less common types of cysts develop that a health care provider finds during a pelvic exam. Solid ovarian cysts that develop after menopause might be cancerous (malignant). That’s why it’s important to have regular pelvic exams.

It is almost never appropriate to aspirate an ovarian cyst for diagnostic purposes. False negative results are common and leakage of cyst contents into the peritoneal cavity potentially increases the stage of any cancer found, decreasing patient survival.

Ovarian cyst ultrasound

Ultrasound is considered the gold standard for the assessment of ovarian cysts. Transvaginal ultrasound is preferred, as the probe proximity to the ovary can result in superior images. If transvaginal ultrasound is not available or not tolerated by the patient, transabdominal ultrasound through a full bladder or transperineal ultrasound in virginal or atrophic women can still provide helpful, although limited, information. In some cases, ultrasound can specifically diagnose the type of ovarian cyst, especially if certain characteristic findings are present (Box 1). Figures 6– 11 illustrate and describe characteristic findings seen with simple ovarian cysts, hemorrhagic corpus luteum cysts, dermoid cysts, endometriomas, and malignant cysts 70.

Identifying certain ovarian cyst characteristics is especially important in differentiating benign from malignant processes. The ten “Simple Rules” are five ultrasound features indicative of benign cysts (B-features) and five ultrasound features indicative of a malignant cysts (M-features) based on the presence of tumor morphology, degree of vascularity, and ascites (Table 1) 71.

Box 1. Characteristics of Simple and Malignant ovarian cysts

| Simple ovarian cyst | Malignant ovarian cyst |

|---|---|

|

|

Table 1. “Simple Rules” differentiating Benign and Malignant Cysts

| Benign (B) features | Malignant (M) features |

|---|---|

| B1 unilocular cyst a B2 solid components present, but <7 mm B3 acoustic shadows b B4 smooth multilocular tumor, largest diameter <100 mm B5 no blood flow; color score 1 | M1 irregular solid tumor M2 ascites a M3 at least 4 papillary structures M4 irregular multilocular-solid tumor, largest diameter ≥100 mm b M5 very strong flow; color score 4 |

| If only B features are present → benign tumor If only M features are present → malignant tumor If both B and M features or neither B nor M features present → inconclusive | |

Footnote:

a Most predictive feature.

a Least predictive feature.

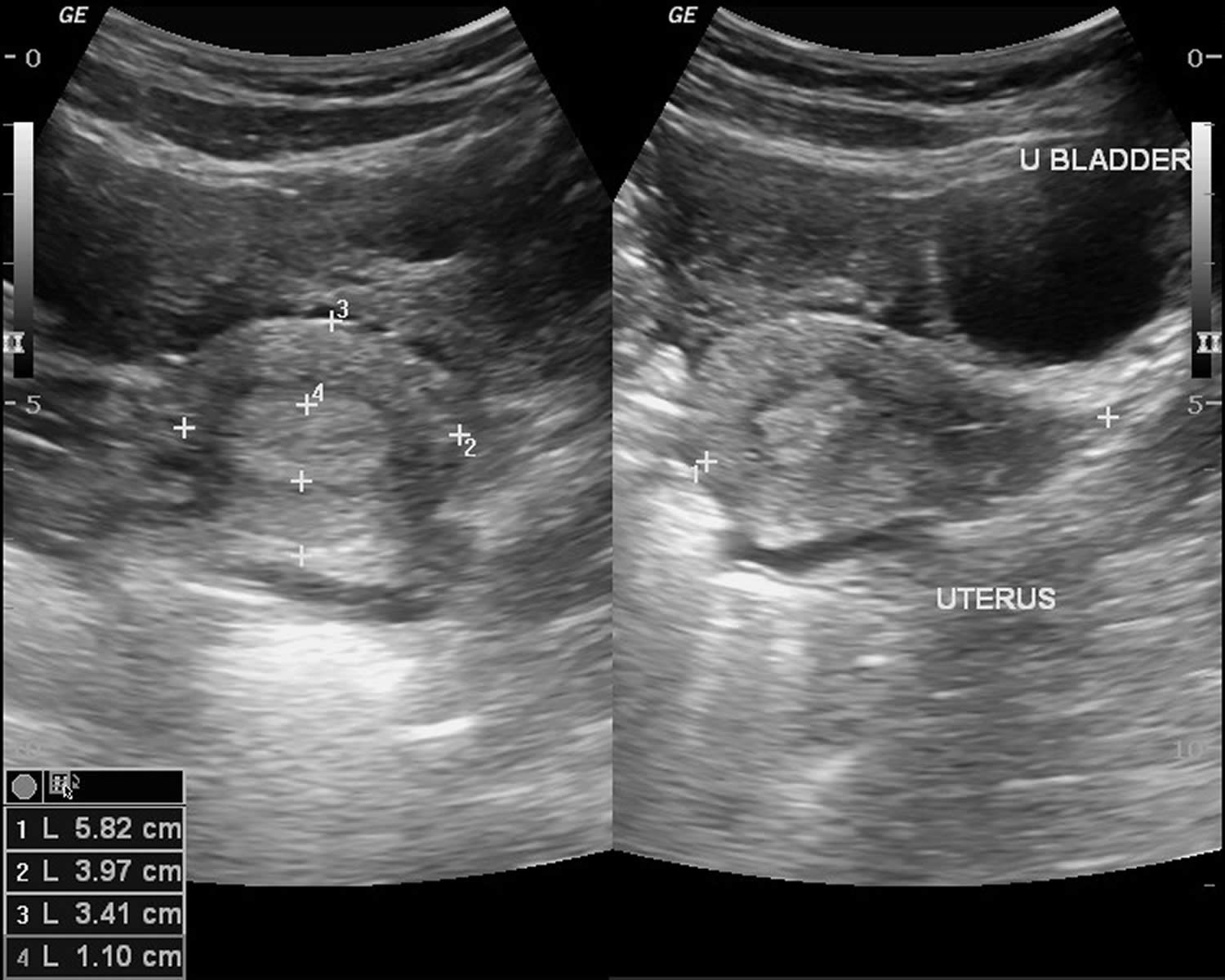

[Source 17, 72 ]Figure 6. Ovarian cyst ultrasound

[Source 73 ]Figure 7. Ovarian follicular cyst

Footnote: There is a 5.5 cm anechoic lesion in the left ovary (there are a few artifactual low level echoes on some images). There are a few round structures at the border (compatible with a normal cumulus oophorus), but no wall thickening, nodularity, papillary projection or thickened septation. No flow on color Doppler imaging. This is an example of a normal ovarian follicular cyst. The ovarian follicular cyst is on the larger size (5.5 cm), but the young/premenopausal status of the patient and the lack of any aggressive features is compatible with a dominant Graafian follicle that failed to rupture. These classically resolve in 1-2 menstrual cycles and persistent cysts raise other lesions into the differential diagnosis (such as serous cystadenoma), although other options on the differential would be much less common in this age than a physiologic cyst. Some follow up a follicular cyst between 5-7 cm with ultrasound in one year, to ensure that it resolves. MRI is usually performed if there are possible aggressive features or if the cyst is >7 cm.

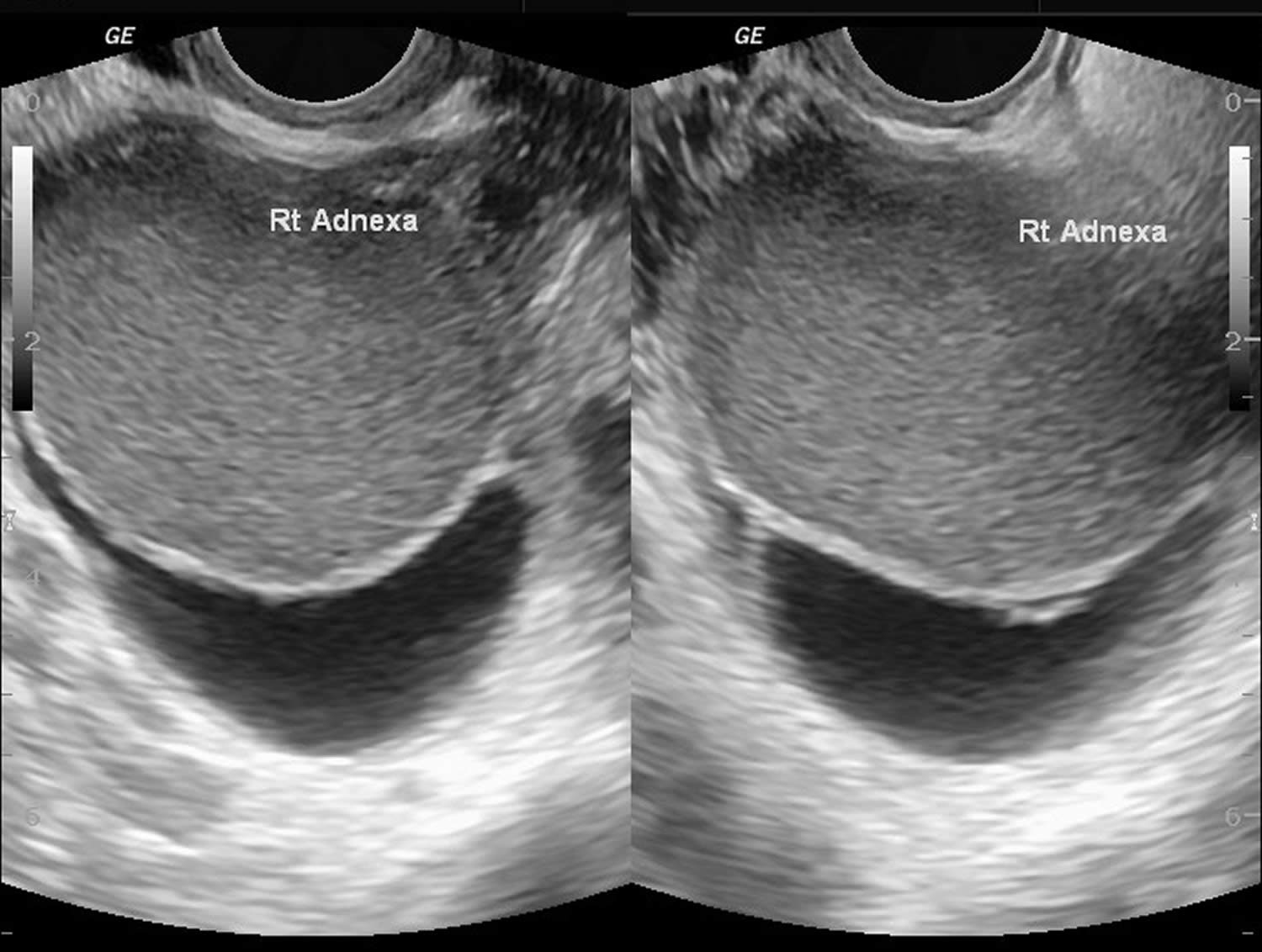

[Source 74 ]Figure 8. Hemorrhagic corpus luteum cysts

Footnote: Severe pain in lower abdomen. LNMP – 20 days back. Ultrasonography was done after 3 hours of the onset of pain. Empty uterine cavity. A collapsed cyst in left ovary. Free fluid in pelvis and hepato-renal region. Findings are suggestive of ruptured hemorrhagic ovarian cyst with hemoperitoneum. Urine pregnancy test was negative. Hb level was 10.5 gm/dL. Laparoscopy was done 3 hours after ultrasonography. Findings confirmed ruptured corpus luteum cyst.

[Source 75 ]Figure 9. Ovarian dermoid cysts

Footnote: Voluminous formation containing numerous echogenic balls floating in an anechoic liquid. In the posterior region, there are echogenic structures with posterior acoustic shadow probably due to calcifications, hair strands, or foci of fat. The appearance of cysts containing multiple internal floating balls is a very rare presentation of the dermoid cyst, but is considered pathognomonic for this entity and was first described in 1991 76, 77. These internal floating balls may be single or multiple, measuring around 5 to 40 mm, composed of keratin, fibrin, hemosiderin, hair, and fat in different proportions and their mechanism of formation has not been well defined yet.

[Source 78 ]Figure 10. Endometrioma

Footnote: Large right adnexal cystic lesion with homogeneous echogenic content. Mild free fluid at the pelvis. Surgically confirmed case of right ovarian chocolate cyst.

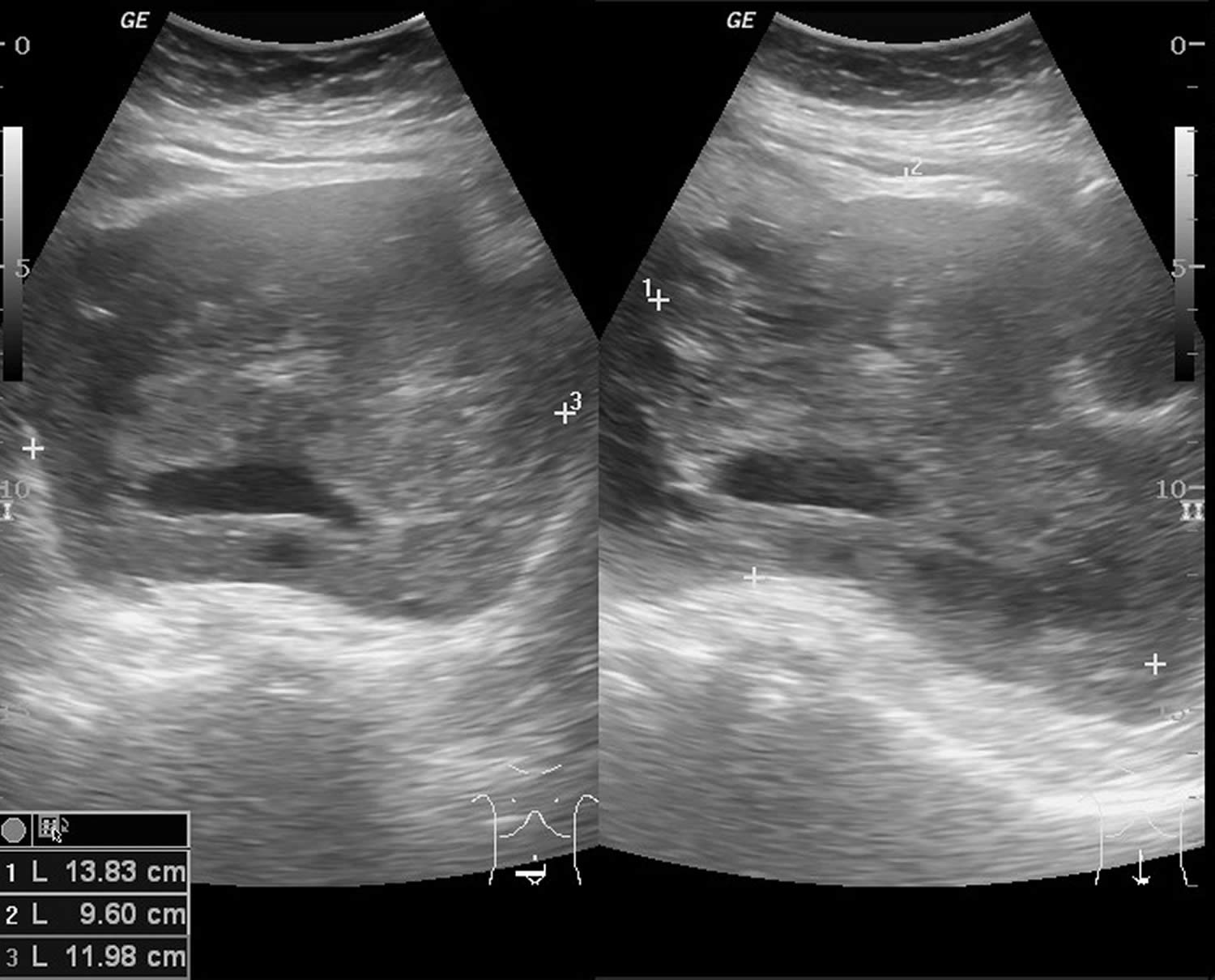

[Source 79 ]Figure 11. Malignant ovarian cyst

Footnote: 69 years old female with lower abdominal pain, weight loss and distension of abdomen. Ultrasound showed solid cystic mass in pelvis with vascularity on doppler. Ovaries are not seperately seen. The uterus is normal. Another solid hypoechoic hepatic nodule in segment V with ascites. CT scan performed the following day (not shown) – similar findings of ovarian tumor and hepatic solitary metastasis. Ascites fluid tapping showed malignant cells.

[Source 80 ]Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a valuable tool when ultrasound is inconclusive or limited. The advantages of MRI are that it is very accurate and it provides additional information on the composition of soft-tissue tumors.8 On the other hand, MRI is more expensive, is usually less available, and is more inconvenient for the patient than ultrasound. MRI for the evaluation of ovarian cysts is usually ordered with contrast, unless contraindicated.8 In one study of MRI as second-line imaging for indeterminate cysts, contrast-enhanced MRI contributed to a greater change in the probability of ovarian cancer compared with computed tomography (CT), Doppler ultrasound, or MRI without contrast.12 This may result in a reduction in unnecessary surgeries and in an increase in proper referrals in cases of suspected malignancy.

Computed Tomography (CT)

Computed tomography (CT) is usually not used in the evaluation of ovarian cysts. CT offers poor discrimination of soft tissue and exposes the patient to more radiation than does ultrasound or MRI. The utility of CT is primarily in the preoperative staging of a suspected ovarian cancer.13 Cysts discovered via CT scan should be further evaluated using ultrasonography.

Ovarian cyst differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of benign ovarian cysts includes:

- Simple cysts

- Hemorrhagic corpus luteum cysts

- Dermoids (mature cystic teratomas)

- Endometriomas

- Pedunculated fibroids

- Hydrosalpinges

- Paratubal and paraovarian cysts

- Peritoneal inclusion cysts (also known as pseudocysts)

- Pelvic kidneys

- Appendiceal or diverticular abscess

- Ectopic pregnancy

The diagnosis of an ovarian cyst is most often made based on imaging rather than by physical examination, laboratory testing, or diagnostic procedures.

The differential diagnosis for pain in women with ovarian cysts include tubo-ovarian abscess, ruptured ectopic, ruptured hemorrhagic cyst, and ovarian torsion 81.

Ovarian cyst treatment

Ovarian cyst treatment depends on your age, the type and size of your cyst, and your symptoms. Management of patients with simple ovarian cysts should follow the algorithm shown in Figures 12 and 13 below. Your doctor might suggest 82:

- Watchful waiting. In many cases you can wait and be re-examined to see if the cyst goes away within a few months. This is typically an option — regardless of your age — if you have no symptoms and an ultrasound shows you have a simple, small, fluid-filled cyst. Your doctor will likely recommend that you get follow-up pelvic ultrasounds at intervals to see if your cyst changes in size.

- Medication. Your doctor might recommend hormonal contraceptives, such as birth control pills, to keep ovarian cysts from recurring. However, birth control pills won’t shrink an existing cyst.

- Surgery. Your doctor might suggest removing an ovarian cyst that is large, doesn’t look like a functional cyst, is growing, continues through two or three menstrual cycles, or causes pain. The National Institutes of Health estimates that 5% to 10% of women have surgery to remove an ovarian cyst. Only 13% to 21% of these cysts are cancerous 83. An ovarian cyst that develops after menopause is sometimes cancer. In this case, you may need to see a gynecologic cancer specialist. You might need surgery to remove your uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes and ovaries. You may also need chemotherapy or radiation.

Your ovarian cyst may require surgery if you are past menopause or if your cyst:

- Does not go away after several menstrual cycles

- Gets larger

- Looks unusual on the ultrasound

- Causes pain

If your ovarian cyst does not require surgery, your doctor may:

- Talk to you about pain medicine. Your doctor may recommend over-the-counter medicine or prescribe stronger medicine for pain relief.

- Prescribe hormonal birth control if you have cysts often. Hormonal birth control, such as the pill, vaginal ring, shot, or patch, help prevent ovulation. This may lower your chances of getting more cysts.

Figure 12. Simple ovarian cyst management algorithm

[Source 17 ]Figure 13. Ovarian cyst management algorithm

[Source 17 ]Ovarian cyst with a High Likelihood of Malignancy

Women with ovarian cysts with a high likelihood of malignancy should be referred directly to a gynecologic oncologist. High likelihood of malignancy exists if malignant features are found on ultrasound, in women with a personal history or a first-degree relative with history of ovarian or breast cancer, or if cancer antigen 125 (CA 125) is >35 (postmenopausal women) or CA 125 >200 (premenopausal women) (Figure 13). Direct referral to and treatment by gynecologic oncologists has been shown to improve survival rates in women with ovarian cancer 84, 85, 86.

Ovarian cyst with an Indeterminate Likelihood of Malignancy

For women with ovarian cysts with an intermediate likelihood of malignancy, further workup is warranted. The most cost-effective test is a second ultrasound and a second opinion at a tertiary center. Obtaining the CA 125 level can be helpful in this instance (Figure 13).

Ovarian cyst with an Unclear Likelihood of Malignancy but Likely Benign

For women with ovarian cysts with an unclear likelihood of malignancy but most likely benign, repeat ultrasound in 6 to 12 weeks is warranted 81. There are no official guidelines as to when to stop serial imaging, but one or two ultrasounds to confirm size and morphologic stability has been suggested 87. Of course, once a lesion has resolved, there is no need for further imaging.

Ovarian cyst surgery

Surgery may be recommended if your ovarian cyst is very large or causing symptoms or if cancer is suspected.

If your ovarian cyst requires surgery, your doctor will either remove just the cyst or the entire ovary. Some cysts can be removed without removing the ovary (ovarian cystectomy). In some cases, the ovary with the cyst is removed (oophorectomy).

Surgery can be done in two different ways:

- Laparoscopy. With this surgery, the doctor makes a very small cut above or below your belly button to look inside your pelvic area and remove the cyst with a laparoscope and instruments inserted through small cuts in your abdomen. This is often recommended for smaller cysts that look benign (not cancerous) on the ultrasound.

- Laparotomy. Your doctor may choose this method if the cyst is large or cancer is a concern. This surgery uses a larger cut in the abdomen to remove the cyst. The cyst is then tested for cancer. If it is likely to be cancerous, it is best to see a gynecologic oncologist, who may need to remove the ovary and other tissues, like the uterus.

If a cystic mass is cancerous, your doctor will likely refer you to a gynecologic cancer specialist. You might need to have your uterus, ovaries and fallopian tubes removed (total hysterectomy) and possibly chemotherapy or radiation. Your doctor is also likely to recommend surgery when an ovarian cyst develops after menopause.

Treating conditions that cause ovarian cysts

If you have been diagnosed with a condition that can cause ovarian cysts, such as endometriosis or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), your treatment may be different.

For example, endometriosis may be treated with painkillers, hormone medication, and/or surgery to remove or destroy areas of endometriosis tissue.

Ovarian cyst prognosis

Most ovarian cysts are found incidentally, are asymptomatic, and tend to be benign (not cancer) with spontaneous resolution leading to an overall favorable prognosis 20. Overall, 70% to 80% of follicular cysts resolve spontaneously 20. The potential of benign ovarian cystadenoma to become malignant has been postulated but remains unproven 20. Less aggressive tumors of low malignant potential run a benign course. The overall survival in these cases is 86.2% at five years 88. Malignant change can occur in a few cases of dermoid cysts (associated with extremely poor prognosis) and endometriosis 20. If an ovarian cyst is suspected to be malignant, the prognosis is usually poor since ovarian cancer tends to be diagnosed in the advanced stages 20.

- Farghaly SA. Current diagnosis and management of ovarian cysts. Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2014 ;41(6):609-612.[↩][↩][↩]

- Kristjansdottir B, Levan K, Partheen K, Carlsohn E, Sundfeldt K. Potential tumor biomarkers identified in ovarian cyst fluid by quantitative proteomic analysis, iTRAQ. Clin Proteomics. 2013 Apr 4;10(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1559-0275-10-4[↩]

- Ovarian cysts. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ovarian-cysts/symptoms-causes/syc-20353405[↩]

- Ovarian Cysts. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/ovarian-cysts[↩][↩][↩]

- Lee S, Kim YH, Kim SC, Joo JK, Seo DS, Kim KH, Lee KS. The effect of tamoxifen therapy on the endometrium and ovarian cyst formation in patients with breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018 Sep;61(5):615-620. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2018.61.5.615[↩][↩]

- Kelleher CM, Goldstein AM. Adnexal masses in children and adolescents. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;58(1):76-92. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000084[↩]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 174: Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128(5):e210-e226. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001768[↩]

- The Office on Women’s Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Ovarian cysts. https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/ovarian-cysts[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Bottomley C, Bourne T. Diagnosis and management of ovarian cyst accidents. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009 Oct;23(5):711-24. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.02.001[↩][↩][↩]

- Idris S, Daud S, Ahmad Sani N, Tee Mei Li S. A Case of Twisted Ovarian Cyst in a Young Patient and Review of the Literature. Am J Case Rep. 2021 Nov 17;22:e933438. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.933438[↩]

- Kolluru V, Gurumurthy R, Vellanki V, Gururaj D. Torsion of ovarian cyst during pregnancy: a case report. Cases J. 2009 Dec 31;2:9405. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-9405[↩]

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Ovarian cysts. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ovarian-cysts/home/ovc-20341904[↩][↩]

- Ross, E.K. (2013). Incidental Ovarian Cysts: When to Reassure, When to Reassess, When to Refer. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine; 80(8): 503–514. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23908107[↩]

- Kiemtoré S, Zamané H, Sawadogo YA, Sib RS, Komboigo E, Ouédraogo A, Bonané B. Diagnosis and management of a giant ovarian cyst in the gravid-puerperium period: a case report. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019 Dec 26;19(1):523. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2678-8[↩]

- De Lima SHM, dos Santos VM, Daros AC, Campos VP, Modesto FRD. A 57-year-old Brazilian woman with a giant mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;4:82. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-82[↩]

- Bhasin S k, Kumar V, Kumar R. Giant ovarian cyst: a case report. JK Sci. 2014;16:3.[↩]

- Ovarian Cysts. https://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/womens-health/ovarian-cysts[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2016). Screening for Ovarian Cancer. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/ovarian-cancer-screening[↩]

- Horowitz, N.S. (2011). Management of adnexal masses in pregnancy. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynecology; 54: 519–527. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22031242[↩]

- Mobeen S, Apostol R. Ovarian Cyst. [Updated 2022 Jun 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560541[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Jain, K.A. (2002), Sonographic Spectrum of Hemorrhagic Ovarian Cysts. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, 21: 879-886. https://doi.org/10.7863/jum.2002.21.8.879[↩]

- Khati NJ, Kim T, Riess J. Imaging of Benign Adnexal Disease. Radiol Clin North Am. 2020 Mar;58(2):257-273. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2019.10.009[↩]

- Nezhat F, Apostol R, Mahmoud M, el Daouk M. Malignant transformation of endometriosis and its clinical significance. Fertil Steril. 2014 Aug;102(2):342-4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.04.050[↩]

- Nezhat FR, Apostol R, Nezhat C, Pejovic T. New insights in the pathophysiology of ovarian cancer and implications for screening and prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Sep;213(3):262-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.044[↩]

- Killackey MA, Neuwirth RS. Evaluation and management of the pelvic mass: a review of 540 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1988 Mar;71(3 Pt 1):319-22.[↩]

- Pradhan P, Thapa M. Dermoid Cyst and its bizarre presentation. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2014 Apr-Jun;52(194):837-44.[↩]

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Symptoms and causes of Ovarian cysts. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ovarian-cysts/symptoms-causes/dxc-20341906[↩]

- Manique MES, Ferreira AMAP. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Adolescence: Challenges in Diagnosis and Management. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2022 Apr;44(4):425-433. English. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1742292[↩]

- Jones HW, Rock JA, eds. Te Linde’s Operative Gynecology, 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015.[↩]

- Pakhomov SP, Orlova VS, Verzilina IN, Sukhih NV, Nagorniy AV, Matrosova AV. Risk Factors and Methods for Predicting Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (OHSS) in the in vitro Fertilization. Arch Razi Inst. 2021 Nov 30;76(5):1461-1468. doi: 10.22092/ari.2021.355581.1700[↩]

- Stany MP, Hamilton CA. Benign disorders of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008 Jun;35(2):271-84, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2008.03.004[↩]

- Figg WD 2nd, Cook K, Clarke R. Aromatase inhibitor plus ovarian suppression as adjuvant therapy in premenopausal women with breast cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15(12):1586-7. doi: 10.4161/15384047.2014.972783[↩]

- LE Donne M, Alibrandi A, Ciancimino L, Azzerboni A, Chiofalo B, Triolo O. Endometrial pathology in breast cancer patients: Effect of different treatments on ultrasonographic, hysteroscopic and histological findings. Oncol Lett. 2013 Apr;5(4):1305-1310. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1156[↩]

- Tresa A, Rema P, Suchetha S, Dinesh D, Sivaranjith J, Nath AG. Hypothyroidism Presenting as Ovarian Cysts-a Case Series. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2021 Dec;12(Suppl 2):343-347. doi: 10.1007/s13193-020-01263-8[↩]

- Heling, K.-.-S., Chaoui, R., Kirchmair, F., Stadie, S. and Bollmann, R. (2002), Fetal ovarian cysts: prenatal diagnosis, management and postnatal outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 20: 47-50. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00725.x[↩]

- Victoria L. Holt, Kara L. Cushing-Haugen, Janet R. Daling, Risk of Functional Ovarian Cyst: Effects of Smoking and Marijuana Use according to Body Mass Index, American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 161, Issue 6, 15 March 2005, Pages 520–525, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi080[↩]

- Holt VL, Cushing-Haugen KL, Daling JR. Oral contraceptives, tubal sterilization, and functional ovarian cyst risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Aug;102(2):252-8. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00572-6[↩]

- Grimes DA, Jones LB, Lopez LM, Schulz KF. Oral contraceptives for functional ovarian cysts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Apr 29;(4):CD006134. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006134.pub5[↩]

- Young RL, Snabes MC, Frank ML, Reilly M. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of the impact of low-dose and triphasic oral contraceptives on follicular development. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Sep;167(3):678-82. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91570-1[↩]

- Cancer and Steroid Hormone Study of the Centers for Disease Control and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The reduction in risk of ovarian cancer associated with oral-contraceptive use. N Engl J Med. 1987 Mar 12;316(11):650-5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198703123161102[↩]

- Parker WH, Broder MS, Chang E, Feskanich D, Farquhar C, Liu Z, Shoupe D, Berek JS, Hankinson S, Manson JE. Ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy and long-term health outcomes in the nurses’ health study. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;113(5):1027-1037. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a11c64[↩]

- Kurman RJ, Shih IeM. The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: a proposed unifying theory. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010 Mar;34(3):433-43. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181cf3d79[↩]

- Ovarian cancer: recognition and initial management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg122[↩]

- Cicchiello LA, Hamper UM, Scoutt LM. Ultrasound evaluation of gynecologic causes of pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2011 Mar;38(1):85-114, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2011.02.005[↩][↩]

- Amirbekian S, Hooley RJ. Ultrasound evaluation of pelvic pain. Radiol Clin North Am. 2014 Nov;52(6):1215-35. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2014.07.008[↩][↩]

- Morgan M, Molinari A, Jones J, et al. Ruptured ovarian cyst. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/33379[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Guile SL, Mathai JK. Ovarian Torsion. [Updated 2022 Jul 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560675[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Chang HC, Bhatt S, Dogra VS. Pearls and pitfalls in diagnosis of ovarian torsion. Radiographics 2008;28:1355-68. 10.1148/rg.285075130[↩][↩]

- Feng JL, Zheng J, Lei T, Xu YJ, Pang H, Xie HN. Comparison of ovarian torsion between pregnant and non-pregnant women at reproductive ages: sonographic and pathological findings. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2020 Jan;10(1):137-147. doi: 10.21037/qims.2019.11.06[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Growdon Whitfield B, Laufer Marc R. Ovarian and fallopian tube torsion. Uptodate. 2013;4:1–18.[↩]

- Mahonski S, Hu KM. Female Nonobstetric Genitourinary Emergencies. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2019 Nov;37(4):771-784. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2019.07.012[↩][↩][↩]

- Varras M, Tsikini A, Polyzos D, Samara Ch, Hadjopoulos G, Akrivis Ch. Uterine adnexal torsion: pathologic and gray-scale ultrasonographic findings. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2004;31(1):34-8.[↩]

- Nair S, Joy S, Nayar J. Five year retrospective case series of adnexal torsion. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014 Dec;8(12):OC09-13. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9464.5251[↩]

- Huchon C, Fauconnier A. Adnexal torsion: a literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2010;150:8-12. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.02.006[↩]

- Erdemoğlu M, Kuyumcuoglu U, Guzel AI. Clinical experience of adnexal torsion: evaluation of 143 cases. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2011;9(3):171-4.[↩]

- Houry D, Abbott JT. Ovarian torsion: a fifteen-year review. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38:156-9. 10.1067/mem.2001.114303[↩]

- Bider D, Mashiach S, Dulitzky M, Kokia E, Lipitz S, Ben-Rafael Z. Clinical, surgical and pathologic findings of adnexal torsion in pregnant and nonpregnant women. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991 Nov;173(5):363-6.[↩][↩]

- Feng JL, Lei T, Xie HN, Li LJ, Du L. Spectrums and Outcomes of Adnexal Torsion at Different Ages. J Ultrasound Med 2017;36:1859-66. 10.1002/jum.14225[↩]

- Oelsner G, Shashar D. Adnexal torsion. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2006;49:459-63. 10.1097/00003081-200609000-00006[↩]

- Yuk JS, Shin JY, Park WI, Kim DW, Shin JW, Lee JH. Association between pregnancy and adnexal torsion: A population-based, matched case-control study. Medicine 2016;95:e3861. 10.1097/MD.0000000000003861[↩]

- Valsky DV, Esh-Broder E, Cohen SM, Lipschuetz M, Yagel S. Added value of the gray-scale whirlpool sign in the diagnosis of adnexal torsion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010;36:630-4. 10.1002/uog.7732[↩]

- Gerscovich EO, Corwin MT, Sekhon S, Runner GJ, Gandour-Edwards RF. Sonographic appearance of adnexal torsion, correlation with other imaging modalities, and clinical history. Ultrasound Q 2014;30:49-55. 10.1097/RUQ.0000000000000049[↩]

- Mashiach R, Melamed N, Gilad N, Ben-Shitrit G, Meizner I. Sonographic diagnosis of ovarian torsion accuracy and predictive factors. J Ultrasound Med 2011;30:1205-10. 10.7863/jum.2011.30.9.1205[↩]

- Cohen A, Solomon N, Almog B, Cohen Y, Tsafrir Z, Rimon E, Levin I. Adnexal Torsion in Postmenopausal Women: Clinical Presentation and Risk of Ovarian Malignancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Jan 1;24(1):94-97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.09.019[↩]

- Schwartz BI, Huppert JS, Chen C, Huang B, Reed JL. Creation of a Composite Score to Predict Adnexal Torsion in Children and Adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2018 Apr;31(2):132-137. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2017.08.007[↩]

- Gabriel Oelsner, Shlomo B. Cohen, David Soriano, Dahlia Admon, Shlomo Mashiach, Howard Carp, Minimal surgery for the twisted ischaemic adnexa can preserve ovarian function, Human Reproduction, Volume 18, Issue 12, 1 December 2003, Pages 2599–2602, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deg498[↩]

- Oelsner G, Bider D, Goldenberg M, Admon D, Mashiach S. Long-term follow-up of the twisted ischemic adnexa managed by detorsion. Fertil Steril. 1993 Dec;60(6):976-9. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56395-x[↩]

- Wang JH, Wu DH, Jin H, Wu YZ. Predominant etiology of adnexal torsion and ovarian outcome after detorsion in premenarchal girls. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2010 Sep;20(5):298-301. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1254110[↩]

- Pryor RA, Wiczyk HP, O’Shea DL. Adnexal infarction after conservative surgical management of torsion of a hyperstimulated ovary. Fertil Steril. 1995 Jun;63(6):1344-6. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57624-9[↩]

- Ross EK, Kebria M. Incidental ovarian cysts: when to reassure, when to reassess, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med 2013; 80:503–514.[↩]

- Kinkel K, Lu Y, Mehdizade A, Pelte MF, Hricak H. Indeterminate ovarian mass at US: incremental value of second imaging test for characterization–meta-analysis and Bayesian analysis. Radiology. 2005 Jul;236(1):85-94. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2361041618[↩]

- Timmerman D, Van Calster B, Testa A, Savelli L, Fischerova D, Froyman W, Wynants L, Van Holsbeke C, Epstein E, Franchi D, Kaijser J, Czekierdowski A, Guerriero S, Fruscio R, Leone FPG, Rossi A, Landolfo C, Vergote I, Bourne T, Valentin L. Predicting the risk of malignancy in adnexal masses based on the Simple Rules from the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Apr;214(4):424-437. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.01.007[↩]

- Srivastava, S., Kumar, P., Chaudhry, V. et al. Detection of Ovarian Cyst in Ultrasound Images Using Fine-Tuned VGG-16 Deep Learning Network. SN COMPUT. SCI. 1, 81 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-020-0109-6[↩]

- Ovarian follicular cyst. https://radiopaedia.org/cases/ovarian-follicular-cyst-1[↩]

- Ruptured hemorrhagic corpus luteal cyst. https://radiopaedia.org/cases/ruptured-haemorrhagic-corpus-luteal-cyst[↩]

- Yazici B, Erdoğmuş B. Floating ball appearance in ovarian cystic teratoma. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2006 Sep;12(3):136-8.[↩]

- Muramatsu Y, Moriyama N, Takayasu K, Nawano S, Yamada T. CT and MR imaging of cystic ovarian teratoma with intracystic fat balls. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1991 May-Jun;15(3):528-9.[↩]

- Mature cystic ovarian teratoma – floating ball appearance. https://radiopaedia.org/cases/mature-cystic-ovarian-teratoma-floating-ball-appearance[↩]

- Endometrioma. https://radiopaedia.org/cases/endometrioma[↩]

- Ovarian malignancy. https://radiopaedia.org/cases/ovarian-malignancy?lang=us[↩]

- Ross EK, Kebria M. Incidental ovarian cysts: When to reassure, when to reassess, when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med. 2013 Aug;80(8):503-14. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.80a.12155[↩][↩]

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Treatment of Ovarian cysts. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ovarian-cysts/diagnosis-treatment/treatment/txc-20341929[↩]

- NIH consensus conference (1995). Ovarian cancer: screening, treatment, and follow-up. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Ovarian Cancer. JAMA; 273: 491–497. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7837369[↩]

- Engelen, M.J.A., Kos, H.E., Willemse, P.H.B., Aalders, J.G., de Vries, E.G.E., Schaapveld, M., Otter, R. and van der Zee, A.G.J. (2006), Surgery by consultant gynecologic oncologists improves survival in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Cancer, 106: 589-598. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21616[↩]

- Giede KC, Kieser K, Dodge J, Rosen B. Who should operate on patients with ovarian cancer? An evidence-based review. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Nov;99(2):447-61. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.008[↩]

- Vernooij F, Heintz P, Witteveen E, van der Graaf Y. The outcomes of ovarian cancer treatment are better when provided by gynecologic oncologists and in specialized hospitals: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol. 2007 Jun;105(3):801-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.02.030[↩]

- Liu JH, Zanotti KM. Management of the adnexal mass. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jun;117(6):1413-1428. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821c62b6[↩]

- Glanc P, Salem S, Farine D. Adnexal masses in the pregnant patient: a diagnostic and management challenge. Ultrasound Q. 2008 Dec;24(4):225-40. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0b013e31819032f[↩]