18q deletion syndrome

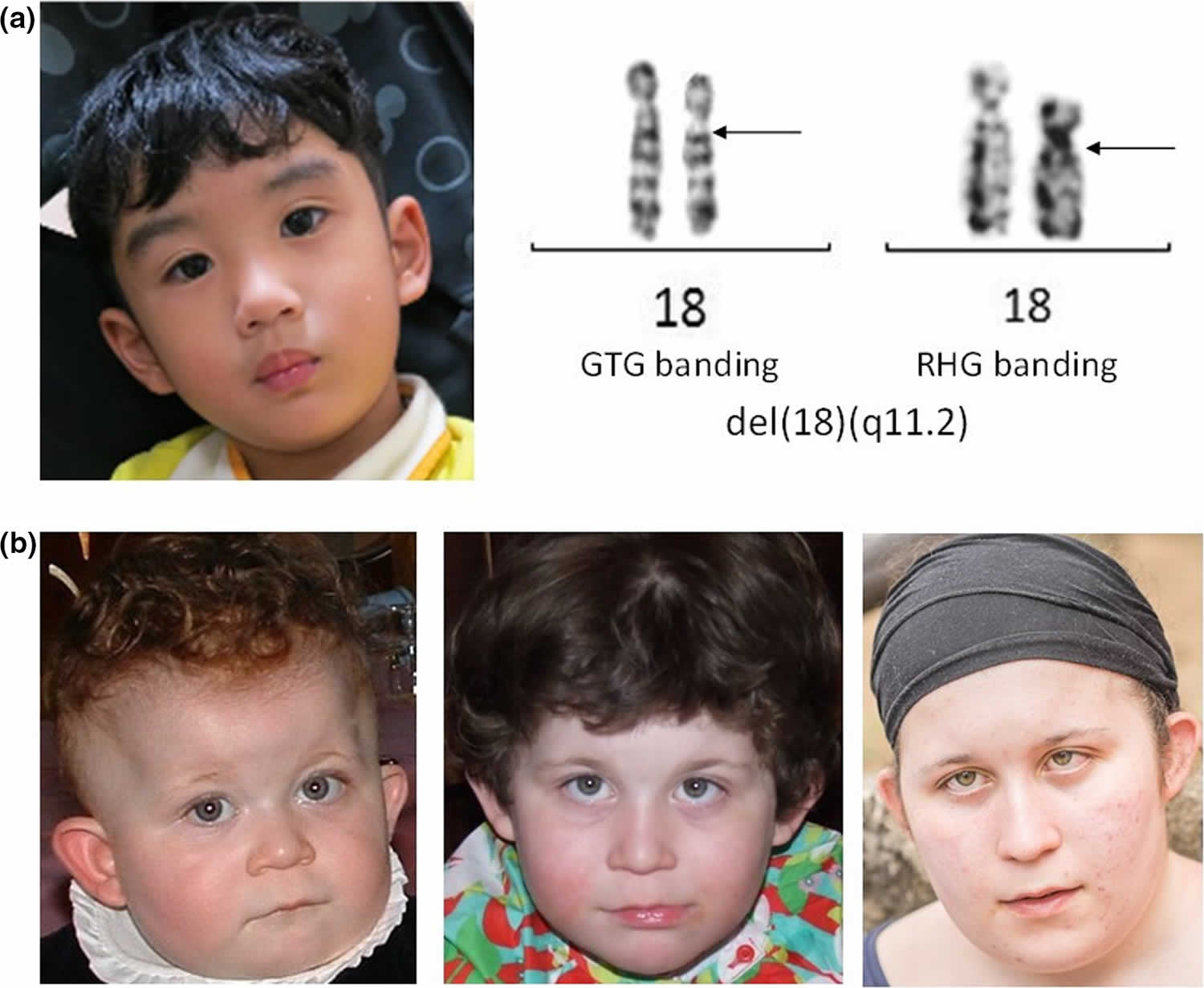

18q deletion syndrome also known as chromosome 18q-syndrome, monosomy 18q syndrome or chromosome 18 long arm deletion syndrome, is a rare chromosomal disorder in which there is deletion of part of the long arm (q) of chromosome 18. There are two groups of people with 18q deletion syndrome: those with deletions involving the end of the chromosome known as distal 18q deletion syndrome (18q21.1‐qter) and those with deletions closer to the centromere known as proximal proximal 18q deletion syndrome (18q11.2‐18q21.1) 1. Associated symptoms and findings may vary greatly in range and severity from case to case. Chromosome 18q deletion syndrome is characterized by mental retardation, small head (microcephaly), short stature, congenital aural atresia, malformations of the hands and feet, poor muscle tone (hypotonia), delayed myelination and abnormalities of the skull and facial (craniofacial) region, such as a , a “carp-shaped” mouth, deeply set eyes, prominent ears, and/or unusually flat, underdeveloped midfacial regions (midfacial hypoplasia) 2. Some affected individuals may also have visual abnormalities, hearing impairment, genital malformations, structural heart defects, and/or other physical abnormalities 3. 18q deletion syndrome usually appears to result from spontaneous (de novo) errors very early during embryonic development that occur for unknown reasons (sporadically).

Most patients with partial 18q deletion present with the distal deletions, and the 18q22.3–18q23 region has been determined as critical for the development of classic phenotypes 4. Proximal interstitial deletions however are relatively rare; nearly all such reports have involved the 18q12 region and patients usually present with short stature, behavioral problems, autism, speech delay, and cleft palate 5.

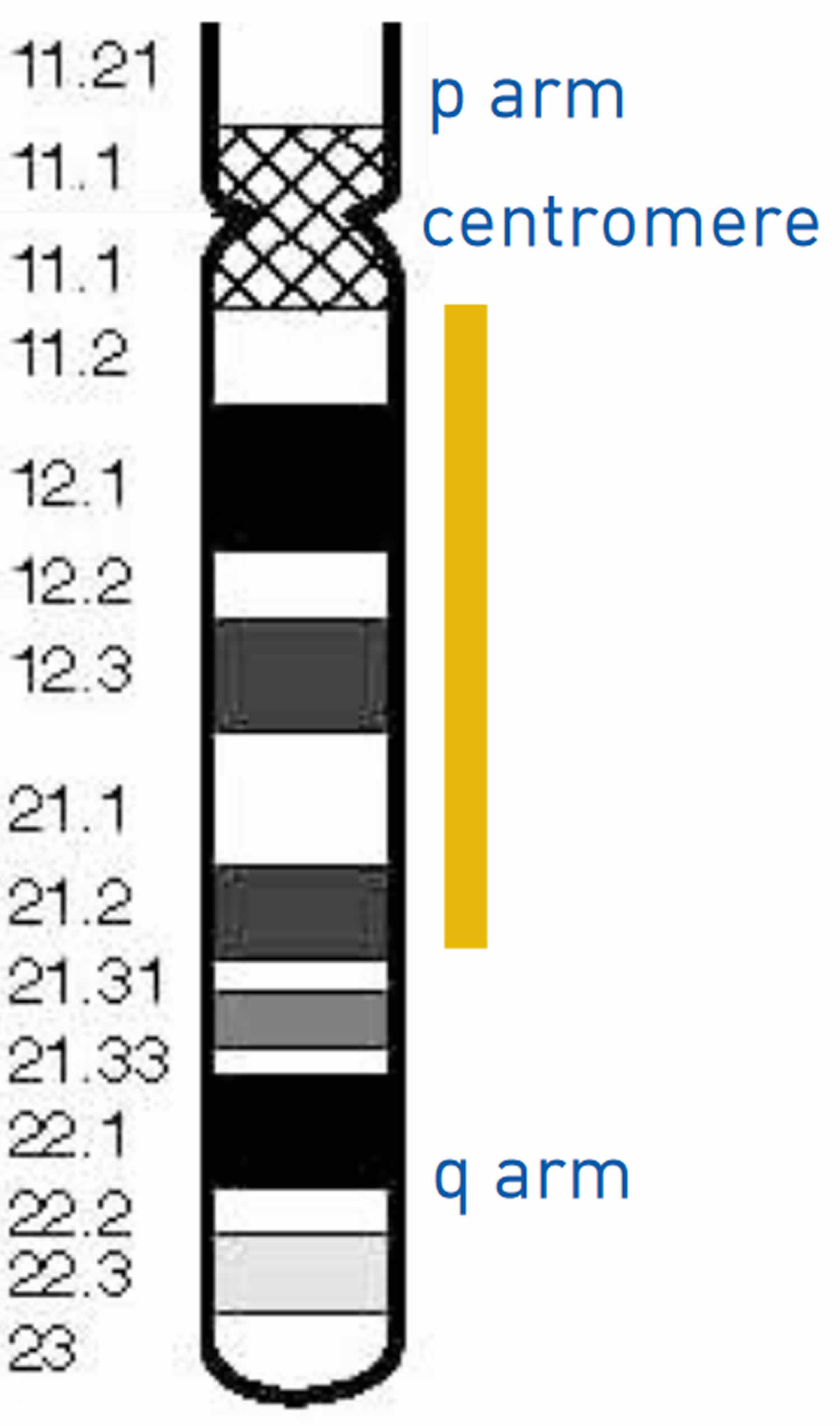

Chromosome 18 in figure 2 below, the bands are numbered outwards starting from where the short and long arms meet (the centromere). A low number, as in q11 in the long arm, is close to the centromere. Regions closer to the centromere are called proximal. A higher number, as in q23, is closer to the end of the chromosome. Regions closer to the end of the chromosome are called distal. Deletions from the q arm of chromosome 18 occur in an estimated 1 in 40,000 to 1 in 55,000 newborns worldwide 6. Most of these deletions occur in the distal region of the chromosome 18 q arm, leading to distal 18q deletion syndrome. Only a small number of these individuals have deletions in the region associated with proximal 18q deletion syndrome. At least 15 people with proximal 18q deletion syndrome have been described in the medical literature 7. It has recently become clear that these deletions result in a separate but recognisable set of features.

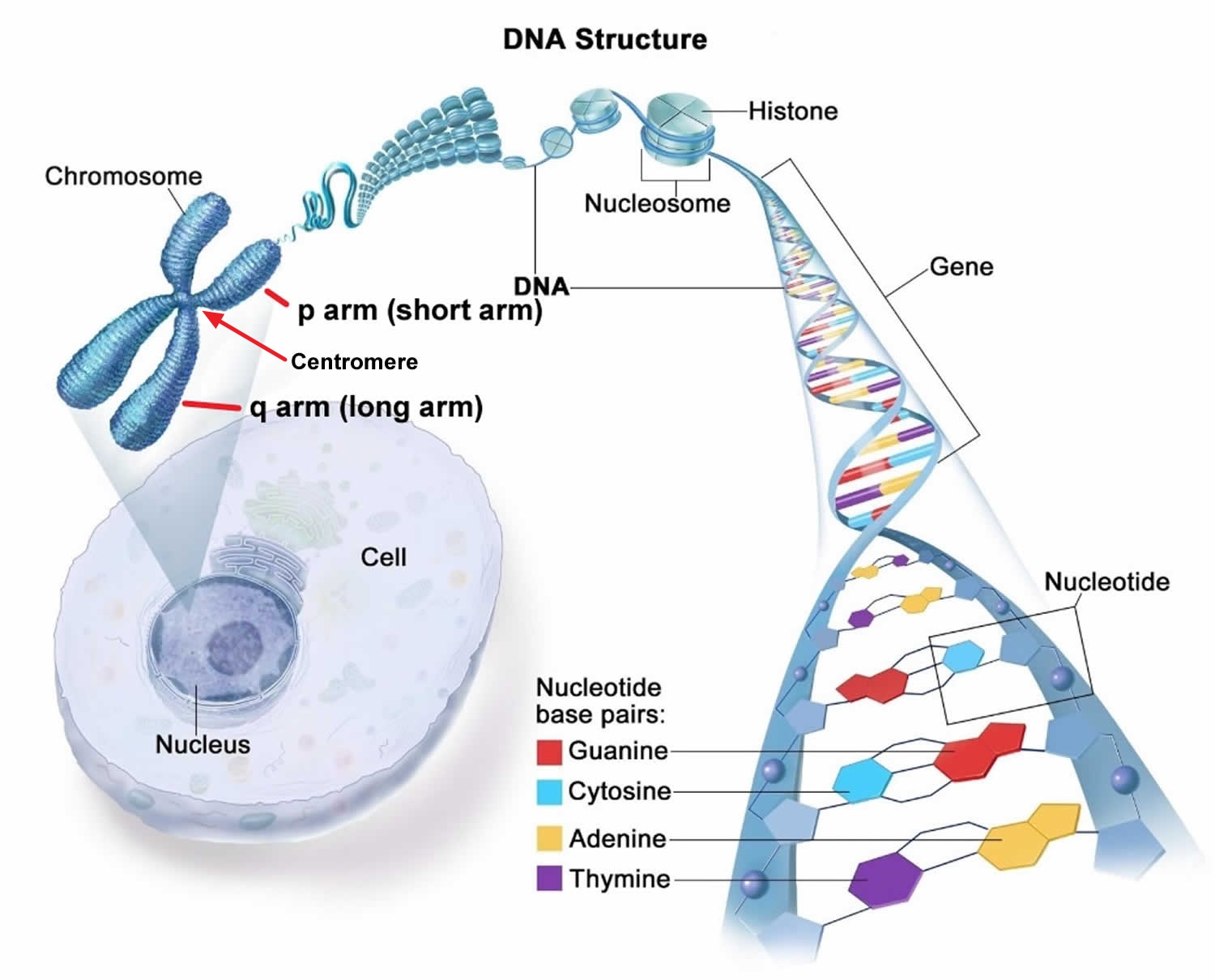

Figure 1. Chromosome structure

Figure 2. Chromosome 18

What are chromosomes?

Chromosomes are the structures that hold your genes. Genes are the individual instructions that tell your body how to develop and keep your body running healthy. In every cell of your body there are 20,000 to 25,000 genes that are located on 46 chromosomes. These 46 chromosomes occur as 23 pairs. You get one of each pair from your mother in the egg, and one of each pair from your father in the sperm. The first 22 pairs are labeled longest to shortest. The last pair are called the sex chromosomes labeled X or Y. Females have two X chromosomes (XX), and males have an X and a Y chromosome (XY). Therefore everyone should have 46 chromosomes in every cell of their body. If a chromosome or piece of a chromosome is missing or duplicated, there are missing or extra genes respectively. When a person has missing or extra information (genes) problems can develop for that individuals health and development.

Each chromosomes has a p and q arm; p (petit) is the short arm and q (next letter in the alphabet) is the long arm. Some of the chromosomes like 13, 14, and 15 have very small p arms. When a karyotype is made the q arm is always put on the bottom and the p on the top. The arms are separated by a region known as the centromere, which is a pinched area of the chromosome. The chromosomes need to be stained in order to see them with a microscope. When stained the chromosomes look like strings with light and dark bands. Each chromosome arm is defined further by numbering the bands, the higher the number, the further that area is from the centromere.

Proximal 18q deletion syndrome

Proximal 18q deletion syndrome also known as proximal chromosome 18q deletion syndrome, monosomy 18q syndrome or proximal 18q deletion, is a chromosome abnormality that occurs when there is a missing (deleted) copy of genetic material from the part of the long arm (q) of chromosome 18 near the center of chromosome 18. The term “proximal” means that the missing piece occurs near the center of the chromosome. Proximal deletions of 18q are interstitial. This is where a piece of the long arm of chromosome 18 is missing, but the tip is still present 8. The severity of proximal 18q deletion syndrome and the signs and symptoms depend on the size and location of the deletion and which genes are involved. Features that often occur in people with proximal chromosome 18q deletion syndrome include delayed development of skills such as sitting, crawling, walking, and speaking; intellectual disability that can range from mild to severe, in particular, vocabulary and the production of speech (expressive language skills) may be delayed and distinctive facial features. The might also have recurrent seizures (epilepsy), low muscle tone (hypotonia), speech and language delays, obesity, and short stature 9. Affected individuals also frequently have behavioral problems such as hyperactivity, aggression, and features of autism spectrum disorder that affect communication and social interaction. Because only a small number of people are known to have proximal 18q deletion, it can be difficult to determine which features should be considered characteristic of the disorder.

Chromosome testing of both parents can provide more information on whether or not the deletion was inherited. In most cases, parents do not have any chromosomal anomaly. However, sometimes one parent is found to have a balanced translocation, where a piece of a chromosome has broken off and attached to another one with no gain or loss of genetic material. The balanced translocation normally does not cause any signs or symptoms, but it increases the risk for having a child with a chromosomal anomaly like a deletion. Treatment is based on the signs and symptoms present in each person.

Is it possible to potty train my daughter who has proximal chromosome 18q deletion syndrome?

While each child is different, most individuals with proximal chromosome 18q deletion syndrome can be toilet trained. The age is generally somewhat later than their peers. Some may need to wear protective clothing or undergarments at night, as nighttime continence is variable and can be more difficult to achieve 8.

How might a proximal 18q deletion alter a child’s ability to learn?

Published medical literature states that learning difficulties for those with proximal 18q deletions are commonly in the moderate to severe range. Three Rare Chromosome Disorder Support Group (Unique) children attend a mainstream school, with the remainder benefiting from a specialist education environment. Many children suffer from poor concentration or a low attention span that can make learning especially challenging. However, the evidence from Rare Chromosome Disorder Support Group (Unique) suggests that reading and writing, to some degree, is possible for some children 10.

How might a proximal 18q deletion affect my child’s ability to communicate?

Problems with language development are a recurrent feature of proximal 18q deletions. Almost half of those in the published literature had speech delay. Sign language can help children communicate their needs. For some, as speech develops they find they no longer have any need for sign language. Speech therapy can be enormously beneficial, enabling some children whose speech is initially delayed to master clear speech with good vocabulary and sentences. However, a small minority of children do not talk 5. There are many reasons for the speech delay, including the link between the ability to learn and the ability to speak. The hypotonia experienced by many children results in weakness in the mouth muscles which as well as insufficient sucking, can also affect the development of speech. Those with a high palate may also have specific difficulty with certain sounds. Experience at Rare Chromosome Disorder Support Group (Unique) suggests that for some children receptive language is markedly better than their expressive language skills –they understand far more than they are able to express. This is backed up by recent reports that noted that five out of the six people showed a striking discrepancy between expressive and receptive language skills, with expressive speech development being much more severely affected. In the published literature a 7-year-old speaks only a few words. A 4-year-old has no expressive speech but his receptive language is intact and he actively communicates using gestures illustrating ideas and demands. A 10-year-old had delayed speech and used signs until the age of 4. She struggled to understand sentences and had problems with articulation but had a desire to communicate and a normal level of vocabulary. A 20-year-old has 30 mono-or disyllabic words, he signs and can obey simple instructions 11.

How can a proximal 18q deletion affect a child’s development and mobility?

Hypotonia, low muscle tone (floppiness), is also common and has been seen in over half of those described in the medical literature. This can result in delays in reaching milestones such as sitting independently, crawling and walking. The evidence in the literature is that children walk independently between the ages of 18 months and 4 years 9 months, at an average age of around 2½ years. However, some children maintain a clumsy gait into adulthood. Early intervention with physiotherapy and occupational therapy is important 11. Mobility can be an issue due to the behavioral problems that affect some children with proximal 18q deletions. Some children suffer from hyperactivity and may feel the need to run everywhere. Other parents describe their children as struggling with depth perception which can also lead to clumsiness and difficulties negotiating uneven surfaces, such as steps.

Proximal 18q deletion syndrome causes

Proximal 18q deletion syndrome is caused by a deletion of genetic material from one copy of chromosome 18. The deletion occurs near the middle of the q arm of the chromosome, typically in an area between regions called 18q11.2 and 18q21.2. The size of the deletion varies among affected individuals. The signs and symptoms of proximal 18q deletion syndrome are thought to be related to the loss of multiple genes from this part of chromosome 18. Researchers are working to determine how the loss of specific genes in this region contributes to the various features of this disorder.

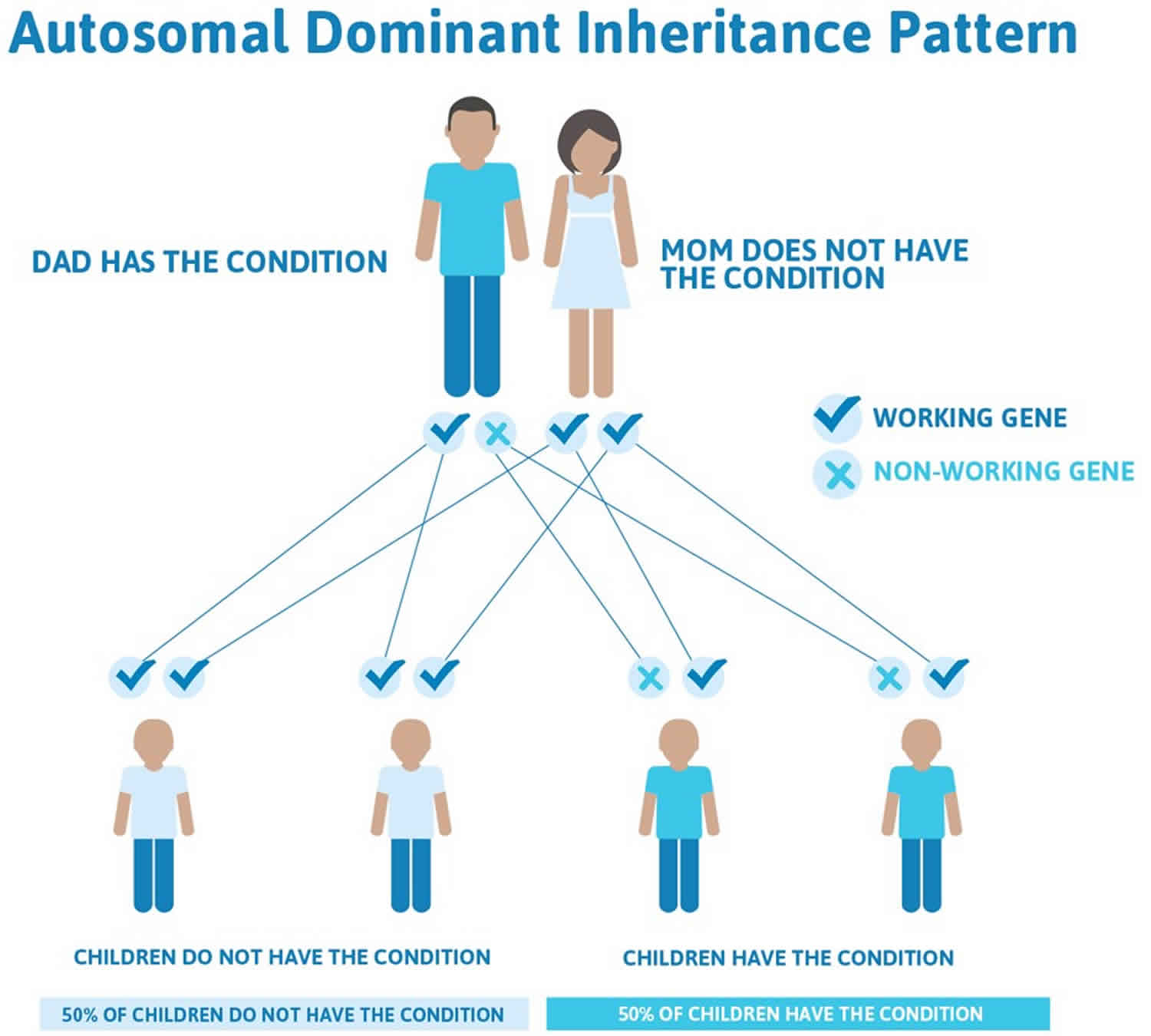

Proximal 18q deletion syndrome inheritance pattern

Proximal 18q deletion syndrome is considered to be an autosomal dominant condition. This means that a deletion in one of the two copies of chromosome 18 in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder’s characteristic features.

However, most cases of proximal 18q deletion syndrome are the result of a new (de novo) deletion and are not inherited from a parent. The deletion occurs most often as a random event during the formation of reproductive cells (eggs or sperm) or in early fetal development. Affected people typically have no history of the disorder in their family.

Figure 3. Proximal 18q deletion syndrome autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Distal 18q deletion syndrome

Distal 18q deletion syndrome is a chromosomal condition that occurs when a piece of the long (q) arm of chromosome 18 is missing. The term “distal” means that the missing piece occurs near one end of the chromosome. Distal 18q deletion syndrome can lead to a wide variety of signs and symptoms among affected individuals. The severity of the condition and the signs and symptoms depend on the size and location of the deletion and which genes are involved.

Some common features of distal 18q deletion syndrome include short stature (often due to growth hormone deficiency), weak muscle tone (hypotonia), hearing loss due to ear canals that are narrow (aural stenosis) or absent (aural atresia), and foot abnormalities such as an inward or upward-turning foot (clubfoot) or feet with soles that are rounded outward (rocker-bottom feet). Eye movement disorders and other vision problems, an opening in the roof of the mouth (cleft palate), an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism), heart abnormalities that are present from birth (congenital heart defects), kidney problems, genital abnormalities, and skin problems may also occur in this disorder. Some affected individuals have mild facial differences such as deep-set eyes, a flat or sunken appearance of the middle of the face (midface hypoplasia), a wide mouth, and prominent ears. These features are often not noticeable except in a detailed medical evaluation.

Distal 18q deletion syndrome can also affect the nervous system. A common neurological feature of this disorder is impaired myelin production (dysmyelination). Myelin is a fatty substance that insulates nerve cells and promotes the rapid transmission of nerve impulses. The formation of a protective myelin sheath around nerve cells (myelination) normally begins before birth and continues into adulthood. In people with distal 18q deletion syndrome, myelination is often delayed and proceeds more slowly than normal; affected individuals may never have normal adult myelin levels. Most people with distal 18q deletion syndrome have neurological problems, although it is unclear to what extent these problems are related to the dysmyelination. These problems include delayed development, learning disabilities, and intellectual disability that can range from mild to severe. Seizures; hyperactivity; mood disorders such as anxiety, irritability, and depression; and features of autism spectrum disorder that affect communication and social interaction may also occur. Some affected individuals have an unusually small head size (microcephaly).

Distal 18q deletion syndrome causes

Distal 18q deletion syndrome is caused by a deletion of genetic material from one copy of chromosome 18 anywhere between a region called 18q21 and the end of the chromosome. The size of the deletion and where it begins vary among affected individuals. The signs and symptoms of distal 18q deletion syndrome are thought to be related to the loss of multiple genes, some of which have not been identified, from this part of chromosome 18. Certain features of the disorder have been associated with the loss of particular genes in this region. People with deletions that include the TCF4 gene usually have signs and symptoms of another genetic condition known as Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, such as severe intellectual disability and breathing problems, in addition to other features of distal 18q deletion syndrome.

Distal 18q deletion syndrome inheritance pattern

Distal 18q deletion syndrome is considered to be an autosomal dominant condition, which means one copy of the deleted region on chromosome 18 in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder’s characteristic features.

However, most cases of distal 18q deletion syndrome are the result of a new (de novo) deletion and are not inherited. The deletion occurs most often as a random event during the formation of reproductive cells (eggs or sperm) or in early fetal development. Affected people typically have no history of the disorder in their family.

In some cases, distal 18q deletion syndrome is inherited, usually from an affected parent with relatively mild signs and symptoms. The condition can also be inherited from an unaffected parent who carries a chromosomal rearrangement called a balanced translocation, in which no genetic material is gained or lost. Individuals with a balanced translocation do not usually have any related health problems; however, the translocation can become unbalanced as it is passed to the next generation. Children who inherit an unbalanced translocation can have a chromosomal rearrangement with extra or missing genetic material. Inheritance of an unbalanced translocation that results in the deletion of genetic material from the distal region of the q arm of chromosome 18 causes distal 18q deletion syndrome.

Figure 4. Distal 18q deletion syndrome autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

18q deletion syndrome causes

Chromosome 18q-syndrome is a chromosomal disorder in which there is deletion (monosomy) of part of the long arm (q) of chromosome 18. Chromosomes are found in the nucleus of all body cells. They carry the genetic characteristics of each individual. Pairs of human chromosomes are numbered from 1 through 22, with an unequal 23rd pair of X and Y chromosomes for males and two X chromosomes for females. Each chromosome has a short arm designated as “p” and a long arm identified by the letter “q.” Chromosomes are further subdivided into bands that are numbered. For example, “18q21” refers to band 21 of the long arm of chromosome 18.

Evidence suggests that individuals with characteristic features of the disorder have deletions from within band 18q21 (e.g., 18q21.3) or 18q22 (e.g., 18q22.2) that may extend to the end (or “terminal”) of chromosome 18q (qter). In some cases, the deletion could be interstitial; that is, in the middle of the chromosome. In addition, in some cases, only a certain percentage of an affected individual’s cells may have the deletion, while other cells may have a normal chromosomal makeup (a finding known as “chromosomal mosaicism”). The range and severity of symptoms may depend on the specific size of the deletion and the percentage of cells with the chromosomal abnormality. Reports suggest that those with 18q- mosaicism tend to have less severe symptoms and findings.

In most cases, Chromosome 18q- syndrome appears to be caused by spontaneous (de novo) errors very early in embryonic development. In such instances, the parents of the affected child usually have normal chromosomes and a relatively low risk of having another child with the chromosomal abnormality.

Less commonly, the deletion may result from a “balanced translocation” in one of the parents. Translocations occur when portions of certain chromosomes break off and are rearranged, resulting in shifting of genetic material and an altered set of chromosomes. If a chromosomal rearrangement is balanced, meaning that it consists of an altered but balanced set of chromosomes, it is usually harmless to the carrier. However, such a chromosomal rearrangement may be associated with an increased risk of abnormal chromosomal development in the carrier’s offspring.

Rare cases have also been reported in which the disorder has appeared to result from a parental chromosomal inversion or other chromosomal rearrangements. An inversion is characterized by breakage of a chromosome in two places and reunion of the segment in the reverse order.

Chromosomal analysis and genetic counseling are typically recommended for parents of an affected child to help confirm or exclude the presence of a balanced translocation or other chromosomal rearrangement in one of the parents.

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

18q deletion syndrome signs and symptoms

18q deletion syndrome symptoms and findings may vary from case to case. However, many infants with chromosome 18q deletion have a low birth weight and growth delays after birth, resulting in short stature. In addition, chromosome 18q deletion syndrome is often characterized by low muscle tone (hypotonia); sudden episodes of uncontrolled electrical activity in the brain (seizures); moderate to severe delays in the acquisition of skills requiring the coordination of mental and physical activities (psychomotor retardation); and varying degrees of mental retardation. Evidence suggests that most individuals with the disorder are affected by profound, severe, or moderate mental retardation. However, mild mental deficiency has been reported in some cases. In addition, some affected children may have behavioral problems, such as abnormally increased activity (hyperactivity), aggressive behavior, and tantrums.

Chromosome 18q-syndrome is also typically associated with malformations of the skull and facial (craniofacial) region. Characteristic craniofacial findings may include an unusually small head (microcephaly); flat, underdeveloped (hypoplastic) midfacial regions; deeply set eyes; a “carp-shaped” mouth; and/or relative protrusion of the lower jaw (mandibular prognathism). Some affected individuals may also have a broad nasal bridge; incomplete closure (clefting) or unusual narrowness of the roof of the mouth (palate); and/or an abnormal groove in the upper lip (cleft lip).

Chromosome 18q deletion syndrome is also often characterized by additional eye (ocular) defects, such as vertical skin folds that may cover the eyes’ inner corners (epicanthal folds); involuntary, rhythmic, rapid eye movements (nystagmus); and/or abnormal deviation of one eye in relation to the other (strabismus). Associated ocular defects may also include abnormally small eyes (microphthalmia); partial absence of ocular tissue from the colored region of the eyes (coloboma of the iris); clouding of the normally transparent front region of the eyes (corneal opacities); defects of the retinas and optic disks; and/or other ocular abnormalities. (The retina is the nerve-rich membrane upon which images are focused at the back of the eye; its specialized nerve cells convert light into nerve impulses that are transmitted to the brain via the optic nerve. The optic disk, also known as the “blind spot,” is the region where fibers of the retina become part of the optic nerve.) Such ocular defects may result in varying degrees of visual impairment.

Some individuals with chromosome 18q deletion syndrome may also have malformations of the ears. These may include unusually prominent ears and/or abnormally narrow (stenotic) or absent (atretic) external ear canals, with associated hearing impairment.

Chromosome 18q deletion syndrome is also often associated with distinctive abnormalities of the hands and feet, including long, thin, tapered hands; abnormal skin ridge patterns on the fingers and palms; abnormal placement of the thumbs and certain toes; and/or deformities in which the feet are twisted out of shape or position (clubfeet). Some affected individuals may also have rib malformations, hip deformities, and/or other skeletal defects. In addition, abnormal dimples may be present in certain regions, including over the knuckles and the sides of the knees.

Individuals with chromosome 18q-syndrome may also have genital abnormalities. In affected females, there may be underdevelopment of the skin folds surrounding the vaginal opening (hypoplastic labia). In males with the disorder, genital malformations may include undescended testes (cryptorchidism); an abnormally small penis (micropenis) and scrotum; and/or abnormal placement of the urinary opening (hypospadias), such as on the underside of the penis.

Additional physical abnormalities have also been reported in association with the disorder, such as widely spaced nipples; deficiency of a particular antibody (i.e., immunoglobulin A [IgA]) that helps the body to fight certain infections; kidney (renal) defects; and/or other findings. In addition, in over 30 percent of cases, congenital heart defects may be present. Such heart defects have included an abnormal opening in the fibrous partition (septum) that normally separates the upper chambers (atria) or the lower chambers (ventricles) of the heart (atrial or ventricular septal defects); abnormal narrowing (stenosis) of the opening between the pulmonary artery and the right ventricle (pulmonary stenosis); or patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). In patent ductus arteriosus, the channel that is present between the pulmonary artery and the aorta during fetal development fails to close after birth. (The pulmonary artery transports oxygen-poor blood from the right ventricle to the lungs, where the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide occurs. The aorta, the major artery of the body, arises from the left ventricle and supplies oxygen-rich blood to most arteries.) In some individuals with chromosome 18q deletion syndrome, additional physical abnormalities may also be present.

18q deletion syndrome diagnosis

In some cases, chromosome 18q deletion syndrome may be suggested before birth (prenatally) by specialized tests such as ultrasound, amniocentesis, and/or chorionic villus sampling (CVS). During fetal ultrasonography, reflected sound waves create an image of the developing fetus, potentially revealing certain findings that suggest a chromosomal disorder or other developmental abnormalities. With amniocentesis, a sample of fluid that surrounds the developing fetus is removed and analyzed, while CVS involves the removal of tissue samples from a portion of the placenta. Chromosomal analysis performed on such fluid or tissue samples may reveal the presence of monosomy 18q.

18q deletion syndrome is usually diagnosed or confirmed after birth (postnatally) based upon a thorough clinical evaluation, detection of characteristic physical findings, and chromosomal analysis. Specialized tests may also be performed to help detect and/or characterize certain abnormalities that may be associated with the disorder.

18q deletion syndrome treatment

The treatment of chromosome 18q-syndrome is directed toward the specific symptoms that are apparent in each individual. Such disease management may require the coordinated efforts of a team of medical professionals, such as pediatricians; surgeons; neurologists; eye specialists; hearing specialists; physicians who diagnose and treat disorders of the skeleton, muscles, joints, and related tissues (orthopedists); heart specialists (cardiologists); and/or other health care professionals.

In some cases, physicians may recommend surgical correction of certain craniofacial, skeletal, genital, and/or other malformations associated with the disorder. In addition, for those with congenital heart defects, treatment with certain medications, surgical intervention, and/or other measures may be required. The specific surgical procedures performed will depend upon the severity and location of the anatomical abnormalities, their associated symptoms, and other factors.

For individuals with ocular abnormalities, corrective lenses, surgery, and/or other measures may be advised to help improve vision in some cases. In addition, in those with hearing impairment, recommended treatment may include surgical measures and/or the use of specialized hearing aids or additional supportive techniques that may aid communication.

In some cases, anticonvulsant medications may be administered to help prevent, reduce, or control seizures. In addition, for individuals with low levels of certain antibodies (i.e., IgA deficiency), disease management may include regular monitoring and appropriate, supportive measures to help prevent and aggressively treat infections.

Early intervention may also be important in ensuring that affected children reach their potential. Special services that may be beneficial include special education, physical therapy, and/or other medical, social, and/or vocational services. Genetic counseling will also be of benefit for affected individuals and their families. Other treatment for this disorder is symptomatic and supportive.

18q deletion syndrome life expectancy

The experience at Rare Chromosome Disorder Support Group (Unique) suggests that many children with proximal 18q deletion learn to wash and dress themselves, although some will need directions and encouragement to do so. For the most part, toilet training can be achieved, although often somewhat later than their peers, and some continue to need nappies and/or protective clothing during the night. The lack of any major or life-threatening anomalies would suggest a normal life expectancy.

Very few adults with proximal 18q deletion have been described in the published medical literature and Rare Chromosome Disorder Support Group (Unique) has only one member over the age of 18. A 20-year-old is reported in the medical literature. He has some moderate learning difficulties and limited speech. There is also a report of a 67-year-old woman. She has spent much of her life living in a group home, but now participates in a sheltered workshop programme 12.

References- Cody, J. D., Sebold, C., Malik, A., Heard, P., Carter, E., Crandall, A. L., … Hale, D. E. (2007). Recurrent interstitial deletions of proximal 18q: A new syndrome involving expressive speech delay. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 143A(11), 1181–1190. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.31729

- Feenstra, I., Vissers, L. E., Orsel, M., van Kessel, A. G., Brunner, H. G., Veltman, J. A., & van Ravenswaaij‐Arts, C. M. (2007). Genotype‐phenotype mapping of chromosome 18q deletions by high‐resolution array CGH: An update of the phenotypic map. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 143A(16), 1858–1867. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.31850

- Rojnueangnit, K, Charalsawadi, C, Thammachote, W, et al. Clinical delineation of 18q11‐q12 microdeletion: Intellectual disability, speech and behavioral disorders, and conotruncal heart defects. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019; 7:e896. https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.896

- Cody, J. D., Sebold, C., Heard, P., Carter, E., Soileau, B., Hasi‐Zogaj, M., … Hale, D. E. (2015). Consequences of chromsome18q deletions. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 169(3), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31446

- Buysse, K., Menten, B., Oostra, A., Tavernier, S., Mortier, G. R., & Speleman, F. (2008). Delineation of a critical region on chromosome 18 for the del(18)(q12.2q21.1) syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 146A(10), 1330–1334. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.32267

- Distal 18q deletion syndrome. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/distal-18q-deletion-syndrome

- Proximal 18q deletion syndrome. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/proximal-18q-deletion-syndrome

- Proximal deletions of 18q: from q11.2 to q21.2 https://www.rarechromo.org/media/information/Chromosome%2018/18q%20deletions%20from%20%2018q11.2%20to%2018q21.2%20FTNW.pdf

- Proximal 18q- https://www.chromosome18.org/18q/proximal-18q

- Bouquillon S, Andrieux J, Landais E, Duban-Bedu B, Boidein F, Lenne B, Vallée L, Leal T, Doco-Fenzy M, Delobel B. A 5.3Mb deletion in chromosome 18q12.3 as the smallest region of overlap in two patients with expressive speech delay.Eur J Med Genet.2011Mar-Apr;54(2):194-7.

- Bouquillon S, Andrieux J, Landais E, Duban-Bedu B, Boidein F, Lenne B, Vallée L, Leal T, Doco-Fenzy M, Delobel B. A 5.3Mb deletion in chromosome 18q12.3 as the smallest region of overlap in two patients with expressive speech delay. Eur J Med Genet. 2011 Mar-Apr;54(2):194-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2010.11.009

- Tinkle BT, Christianson CA, Schorry EK, Webb T, Hopkin RJ. Long-term survival in a patient with del(18)(q12.2q21.1). Am J Med Genet A. 2003 May 15;119A(1):66-70. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.10217 https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.10217