Acute gastritis

Acute gastritis is a condition in which the stomach lining known as the mucosa is inflamed or swollen. Acute gastritis starts suddenly and lasts for a short time. Acute gastritis will evolve to chronic gastritis, if not treated. For most people, however, acute gastritis isn’t serious and improves quickly with treatment. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacteria infection is the most common cause of gastritis worldwide. However, 60 to 70% of Helicobacter pylori-negative subjects with functional dyspepsia or non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux were also found to have gastritis. In the western population, there is evidence of declining incidence of infectious gastritis caused by Helicobacter pylori with an increasing prevalence of autoimmune gastritis 1. Autoimmune gastritis is more common in women and older people. The prevalence is estimated to be approximately 2% to 5%. However, available data do not have high reliability 1.

Helicobacter pylori-negative gastritis is a consideration when an individual fulfill all four of these criteria (1) A negative triple staining of gastric mucosal biopsies (hematoxylin and eosin, Alcian blue stain and a modified silver stain), (2) A negative Helicobacter pylori culture, (3) A negative IgG Helicobacter pylori serology, and (4) No self-reported history of Helicobacter pylori treatment. In these patients, the cause of gastritis may relate to tobacco smoking, consumption of alcohol, and/or the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or steroids.

Other causes of gastritis include:

- Autoimmune gastritis associated with serum anti-parietal and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies; characterized by chronic atrophic gastritis limited to the corpus and fundus of the stomach that is causing marked diffuse atrophy of parietal and chief cells.

- Gastritis causes include organisms other than Helicobacter pylori such as Mycobacterium avium intracellulare, Herpes simplex, and Cytomegalovirus.

- Gastritis caused by acid reflux. Rare causes of gastritis include collagenous gastritis, sarcoidosis, eosinophilic gastritis, and lymphocytic gastritis.

The stomach lining contains glands that produce stomach acid and an enzyme called pepsin. The stomach acid breaks down food and pepsin digests protein. A thick layer of mucus coats the stomach lining and helps prevent the acidic digestive juice from dissolving the stomach tissue. When the stomach lining is inflamed, it produces less acid and fewer enzymes. However, the stomach lining also produces less mucus and other substances that normally protect the stomach lining from acidic digestive juice.

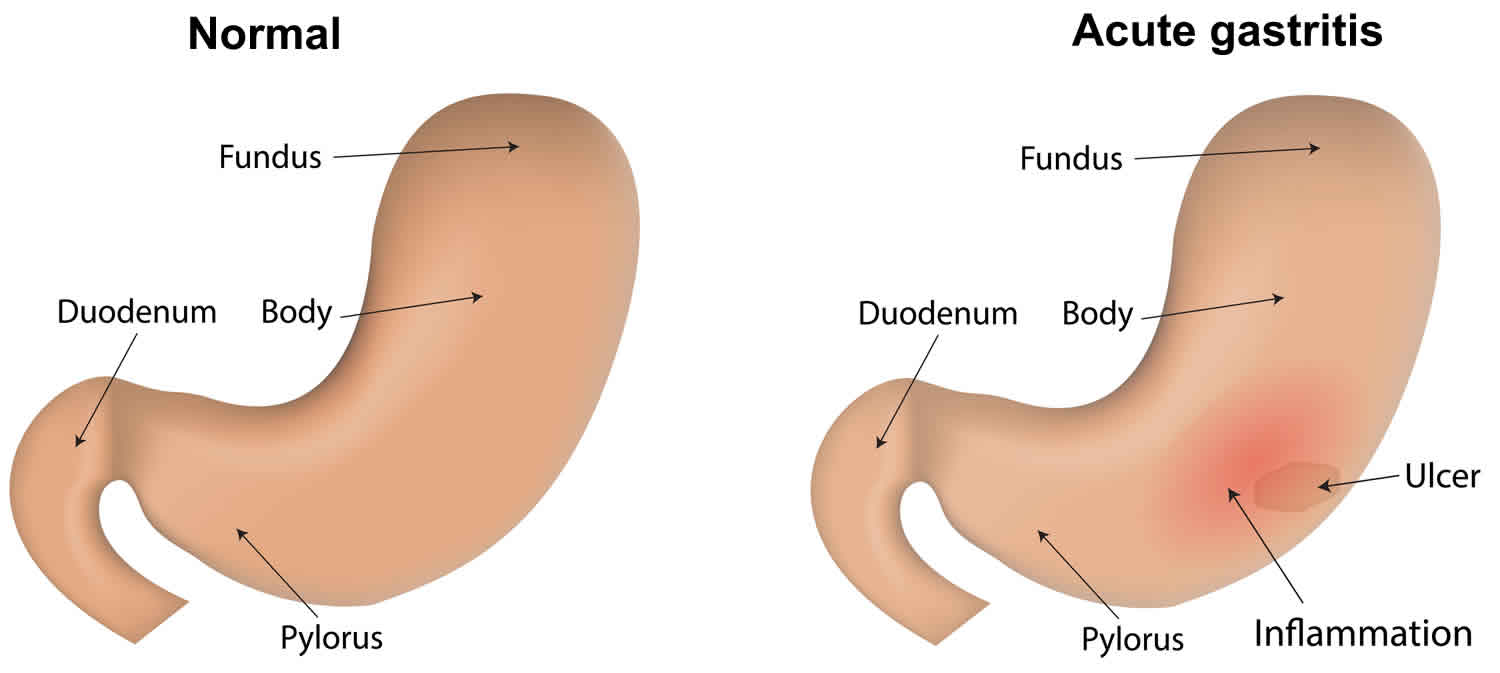

Acute gastritis can be erosive or nonerosive:

- Erosive gastritis can cause the stomach lining to wear away, causing erosions—shallow breaks in the stomach lining—or ulcers—deep sores in the stomach lining.

- Nonerosive gastritis causes inflammation in the stomach lining; however, erosions or ulcers do not accompany nonerosive gastritis.

Clinical presentation, laboratory investigations, gastroscopy, as well as the histological and microbiological examination of tissue biopsies are essential for the diagnosis of gastritis and its causes. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis results in the rapid disappearance of polymorphonuclear infiltration and a reduction of chronic inflammatory infiltrate with the gradual normalization of the mucosa. Mucosal atrophy and metaplastic changes may resolve shortly, but it is not necessarily the outcome of treatment of Helicobacter pylori in all treated patients. Other types of gastritis should be treated based on their causative cause.

Health care providers treat acute gastritis with medications to:

- reduce the amount of acid in the stomach

- treat the underlying cause

In most cases you will be given antacids and other medicines to reduce your stomach acid. This will help ease your symptoms and heal your stomach lining.

If your gastritis is caused by an illness or infection, you should also treat that health problem.

If your gastritis is caused by the Helicobacter pylori bacteria, you will be given medicines to help kill the bacteria. In most cases you will take more than 1 antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor (medicine that reduces the amount of acid in your stomach). You may also be given an antidiarrheal.

Do not have any foods, drinks, or medicines that cause symptoms or irritate your stomach. If you smoke, it is best to quit.

Acute gastritis key points

- Gastritis is a redness and swelling (inflammation) of the stomach lining.

- It can be caused by drinking too much alcohol, eating spicy foods, or smoking.

- Some diseases and other health issues can also cause gastritis.

- Symptoms may include stomach pain, belching, nausea, vomiting, abdominal bleeding, feeling full, and blood in vomit or stool.

- In most cases you will be given antacids and other medicines to reduce your stomach acid.

- Avoid foods or drinks that irritate your stomach lining.

- Stop smoking.

Acute gastritis causes

Gastritis is an inflammation of the stomach lining. Weaknesses or injury to the mucus-lined barrier that protects your stomach wall allows your digestive juices to damage and inflame your stomach lining. A number of diseases and conditions can increase your risk of gastritis, including Crohn’s disease and sarcoidosis, a condition in which collections of inflammatory cells grow in the body.

The causes of acute gastritis can be summarized as follows 2, 3:

- Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis: This is the most common cause of gastritis worldwide. Helicobacter pylori is a type of bacteria—organisms that may cause an infection. Helicobacter pylori infection is common, particularly in developing countries, and the infection often begins in childhood. Many people who are infected with Helicobacter pylori never have any symptoms. Adults are more likely to show symptoms when symptoms do occur. Helicobacter pylori infection:

- causes most cases of gastritis

- typically causes nonerosive gastritis

- may cause acute or chronic gastritis

Researchers are not sure how the Helicobacter pylori infection spreads, although they think contaminated food, water, or eating utensils may transmit the bacteria. Some infected people have Helicobacter pylori in their saliva, which suggests that infection can spread through direct contact with saliva or other body fluids. Socioeconomic and environmental hygiene are the essential factors in the transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection worldwide. These factors include family-bound hygiene, household density, and cooking habits. The pediatric origin of Helicobacter pylori infection is currently considered the primary determinant of Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis in a community 4.

- Helicobacter pylori-negative gastritis: The patients should fulfill all four of these criteria (1) A negative triple staining of gastric mucosal biopsies (hematoxylin and eosin, the Alcian blue stain and a modified silver stain), (2) A negative Helicobacter pylori culture, (3) A negative IgG Helicobacter pylori serology, and (4) No self-reported history of Helicobacter pylori treatment. In these patients, the cause of gastritis may relate to tobacco smoking, consumption of alcohol, and/or the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or steroids.

- Autoimmune gastritis: This is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by chronic atrophic gastritis and associated with raised serum anti-parietal and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies. The loss of parietal cells results in a reduction of gastric acid secretion, which is necessary for the absorption of inorganic iron. Therefore, iron deficiency is commonly a finding in patients with autoimmune gastritis. Iron deficiency in these patients usually precedes vitamin B12 deficiency. The disease is common in young women.

- Gastritis may be the result of infection by organisms other than Helicobacter pylori such as Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, enterococcal infection, Herpes simplex, and cytomegalovirus. Parasitic gastritis may result from cryptosporidium, Strongyloides stercoralis, or anisakiasis infection.

- Gastritis may result from bile acid reflux.

- Radiation gastritis.

- Crohn disease-associated gastritis: This is an uncommon cause of gastritis.

- Collagenous gastritis: This is a rare cause of gastritis. The disease characteristically presents with marked subepithelial collagen deposition accompanying with mucosal inflammatory infiltrate. The exact etiology and pathogenesis of collagenous gastritis are still unclear.

- Eosinophilic gastritis: This is another rare cause of gastritis. The disease could be part of the eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders which is characterized by the absence of known causes of eosinophilia (not secondary to an infection, systematic inflammatory disease, or any other causes to explain the eosinophilia).

- Sarcoidosis-associated gastritis: Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic disorder characterized by the presence of non-caseating granulomas. Although sarcoidosis can affect any body organ, the gastrointestinal tract, including the stomach, is rarely affected.

- Lymphocytic gastritis: This is a rare cause of gastritis. The etiology of lymphocytic gastritis remains unestablished, but an association with Helicobacter pylori infection or celiac disease has been suggested.

- Ischemic gastritis: This is rare and associated with high mortality.

- Vasculitis-associated gastritis: Diseases causing systemic vasculitis can cause granulomatous infiltration of the stomach. An example is Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegner granulomatosis.

- Ménétrier disease: This disease is characterized by- (i) Presence of large gastric mucosal folds in the body and fundus of the stomach, (ii) Massive foveolar hyperplasia of surface and glandular mucous cells, (iii) Protein-losing gastropathy, hypoalbuminemia, and edema in 20 to 100% of patients, and (iv) reduced gastric acid secretion because of loss of parietal cells 5.

Acute gastritis can be caused by diet and lifestyle habits such as:

- Drinking too much alcohol

- Eating spicy foods

- Smoking

- Extreme stress

- Long-term use of aspirin and over-the-counter pain and fever medicines (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or NSAIDs)

Health issues that can lead to acute gastritis include:

- Infections caused by bacteria and viruses

- Major surgery

- Traumatic injury or burns

Some diseases can also cause acute gastritis. These include:

- Autoimmune disorders. When your immune system attacks your body’s healthy cells by mistake.

- Chronic bile reflux. When bile, a fluid that helps with digestion, backs up into your stomach and food pipe (esophagus).

- Pernicious anemia is a condition of macrocytic anemia associated with low cobalamin (vitamin B12) levels and atrophic corpus-fundus gastritis associated with parietal cell antibodies or intrinsic factor autoantibodies.

Risk factors for acute gastritis

Factors that increase your risk of gastritis include:

- Bacterial infection. Although infection with Helicobacter pylori is among the most common worldwide human infections, only some people with the infection develop gastritis or other upper gastrointestinal disorders. Doctors believe vulnerability to the bacterium could be inherited or could be caused by lifestyle choices, such as smoking and diet.

- Regular use of pain relievers. Common pain relievers — such as aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) and naproxen (Aleve, Anaprox) — can cause both acute gastritis and chronic gastritis. Using these pain relievers regularly or taking too much of these drugs may reduce a key substance that helps preserve the protective lining of your stomach.

- Older age. Older adults have an increased risk of gastritis because the stomach lining tends to thin with age and because older adults are more likely to have Helicobacter pylori infection or autoimmune disorders than younger people are.

- Excessive alcohol use. Alcohol can irritate and erode your stomach lining, which makes your stomach more vulnerable to digestive juices. Excessive alcohol use is more likely to cause acute gastritis.

- Stress. Severe stress due to major surgery, injury, burns or severe infections can cause acute gastritis.

- Autoimmune gastritis where your own body attacking cells in your stomach. Autoimmune gastritis is a type of gastritis occurs when your body attacks the cells that make up your stomach lining. This reaction can wear away at your stomach’s protective barrier. Autoimmune gastritis is more common in people with other autoimmune disorders, including Hashimoto’s disease and type 1 diabetes. Autoimmune gastritis can also be associated with vitamin B-12 deficiency.

Other diseases and conditions. Gastritis may be associated with other medical conditions, including HIV/AIDS, Crohn’s disease and parasitic infections.

Acute gastritis prevention

Experts don’t know it is possible to stop gastritis from happening. But you may lower your risk of getting the disease by:

- Having good hygiene habits, especially washing your hands. This can keep you from getting the H. pylori bacteria.

- Not eating or drinking things that can irritate your stomach lining. This includes alcohol, caffeine, and spicy foods.

- Not taking medicines such as aspirin and over-the-counter pain and fever medicines (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or NSAIDS).

Acute gastritis symptoms

Acute gastritis doesn’t always cause signs and symptoms. Sudden onset of epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting have been described to accompany acute gastritis. Many people are asymptomatic or develop minimal dyspeptic symptoms. If not treated the picture may evolve to chronic gastritis. History of smoking, consumption of alcohol, intake of NSAIDs or steroids, allergies, radiotherapy or gall bladder disorders should all be considerations. A history of treatment for inflammatory bowel disease, vasculitic disorders, or eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders might require exploration if no cause of gastritis is apparent.

Each person’s symptoms may vary. The most common symptoms of gastritis include:

- Gnawing or burning ache or pain (indigestion) in your upper abdomen that may become either worse or better with eating

- Stomach upset or pain

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- A feeling of fullness in your upper abdomen after eating

- Belching and hiccups

- Belly or abdominal bleeding

- Loss of appetite

- Blood in your vomit or stool (a sign that your stomach lining may be bleeding)

The symptoms of gastritis may look like other health problems. Always see your healthcare provider to be sure.

If you are vomiting blood, have blood in your stools or have stools that appear black, see your doctor right away to determine the cause.

The most common initial findings for chronic and autoimmune gastritis are (1) hematological disorders such as anemia (iron-deficiency) detected on routine check-up, (2) positive histological examination of gastric biopsies, (3) clinical suspect based on the presence of other autoimmune disorders, neurological symptoms (related to vitamin B12 deficiency) or positive family history 6. Iron-deficiency anemia (based on blood film showing microscopic hypochromic changes as well as iron studies) commonly presents in the early stages of autoimmune gastritis. Achlorhydria causing impairment of iron absorption in the duodenum and early jejunum is the main cause 7. Iron-deficiency anemia could also occur in other types of chronic gastritis.

Autoimmune gastritis is associated with other autoimmune disorders (mainly thyroid diseases) including Hashimoto thyroiditis but also with Addison disease, chronic spontaneous urticaria, myasthenia gravis, Diabetes type 1, vitiligo, and perioral cutaneous autoimmune disorders especially erosive oral lichen planus 8. The association between chronic atrophic autoimmune gastritis and autoimmune thyroid disease earned the name in the early 60s of “thyrogastric syndrome.”

Acute gastritis complications

In most cases, acute gastritis does not lead to complications. In rare cases, acute stress gastritis can cause severe bleeding that can be life threatening.

Left untreated, acute gastritis may lead to stomach ulcers and stomach bleeding. Rarely, some forms of chronic gastritis may increase your risk of stomach cancer, especially if you have extensive thinning of the stomach lining and changes in the lining’s cells.

Acute gastritis diagnosis

The diagnosis of acute gastritis has its basis in histopathological examination of gastric biopsy tissues. While medical history and laboratory tests are helpful, endoscopy and biopsy is the gold standard in making the diagnosis, identifying its distribution, severity, and cause.

Your healthcare provider will give you a physical exam and ask about your past health. You may also have tests including:

- Upper GI (gastrointestinal) series or barium swallow. This X-ray checks the organs of the top part of your digestive system. It checks the esophagus, stomach, and the first part of your small intestine (duodenum). You will swallow a metallic fluid called barium. Barium coats the organs so that they can be seen on the X-ray.

- Upper endoscopy also called esophagogastroduodenoscopy. This test looks at the inside of your esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. It uses a thin, lighted tube, called an endoscope. The tube has a camera at one end. The tube is put into your mouth and throat. Then it goes into your esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. Your healthcare provider can see the inside of these organs. He or she can also take a small tissue sample (biopsy) if needed.

- Blood tests. You will have a test for H. pylori, a type of bacteria that may be in your stomach. Another test will check for anemia. You can get anemia when you don’t have enough red blood cells.

- Stool test. A health care provider may use a stool test to check for blood in the stool, another sign of bleeding in the stomach, and for H. pylori infection. A stool test is an analysis of a sample of stool. The health care provider will give the patient a container for catching and storing the stool. The patient returns the sample to the health care provider or a commercial facility that will send the sample to a lab for analysis.

- Urea breath test. A health care provider may use a urea breath test to check for H. pylori infection. The patient swallows a capsule, liquid, or pudding that contains urea—a waste product the body produces as it breaks down protein. The urea is “labeled” with a special carbon atom. If H. pylori are present, the bacteria will convert the urea into carbon dioxide. After a few minutes, the patient breathes into a container, exhaling carbon dioxide. A nurse or technician will perform this test at a health care provider’s office or a commercial facility and send the samples to a lab. If the test detects the labeled carbon atoms in the exhaled breath, the health care provider will confirm an H. pylori infection in the gastrointestinal tract.

- The diagnosis of autoimmune gastritis centers on laboratory and histological examination. These include: (1) atrophic gastritis of gastric corpus (body) and fundus of the stomach, (2) autoantibodies against the intrinsic factor and the parietal cells, (3) raised serum gastrin levels, (4) serum pepsinogen 1 level and (5) pepsinogen 1 to pepsinogen 2 ratios 9. The most sensitive serum biomarker in autoimmune gastritis is parietal cell antibodies (as compared to intrinsic factor antibodies). Other tests that may be necessary for autoimmune gastritis are gastrin-17, IgG, and anti-H. pylori antibodies, cytokines (such as IL-8), and ghrelin (a growth-hormone-releasing peptide that is produced mainly by the gastric fundus mucosa) 10.

Acute gastritis treatment

Your healthcare provider will make a care plan for you based on:

- Your age, overall health, and past health

- How serious your case is

- How well you handle certain medicines, treatments, or therapies

- If your condition is expected to get worse

- What you would like to do

Reducing the amount of acid in your stomach

The stomach lining of a person with gastritis may have less protection from acidic digestive juice. Reducing acid can promote healing of the stomach lining. Medications that reduce acid include:

- Antacids, such as Alka-Seltzer, Maalox, Mylanta, Rolaids, and Riopan. Many brands use different combinations of three basic salts—magnesium, aluminum, and calcium—along with hydroxide or bicarbonate ions to neutralize stomach acid. Antacids, however, can have side effects. Magnesium salt can lead to diarrhea, and aluminum salt can cause constipation. Magnesium and aluminum salts are often combined in a single product to balance these effects. Calcium carbonate antacids, such as Tums, Titralac, and Alka-2, can cause constipation.

- H2 blockers, such as cimetidine (Tagamet HB), famotidine (Pepcid AC), nizatidine (Axid AR), and ranitidine (Zantac 75). H2 blockers decrease acid production. They are available in both over-the-counter and prescription strengths.

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) include omeprazole (Prilosec, Zegerid), lansoprazole (Prevacid), dexlansoprazole (Dexilant), pantoprazole (Protonix), rabeprazole (AcipHex), and esomeprazole (Nexium). PPIs decrease acid production more effectively than H2 blockers. All of these medications are available by prescription. Omeprazole and lansoprazole are also available in over-the-counter strength.

Treating the underlying cause

Depending on the cause of gastritis, a health care provider may recommend additional treatments.

- Treating Helicobacter pylori infection with antibiotics is important, even if a person does not have symptoms from the infection. Curing the Helicobacter pylori infection often cures the gastritis and decreases the chance of developing complications, such as peptic ulcer disease, MALT lymphoma, and gastric cancer. A triple-therapy of clarithromycin/proton-pump inhibitor/amoxicillin for 14 to 21 days is considered the first line of treatment. Clarithromycin is preferred over metronidazole because the recurrence rates with clarithromycin are far less compared to a triple-therapy using metronidazole. However, in areas where clarithromycin resistance is known, metronidazole is the option of choice. Quadruple bismuth containing therapy would be of benefit, particularly if using metronidazole 11. After two eradication failures, H. pylori culture and tests for antibiotic resistance should be a consideration.

- Avoiding the cause of reactive gastritis can provide some people with a cure. For example, if prolonged NSAID use is the cause of the gastritis, a health care provider may advise the patient to stop taking the NSAIDs, reduce the dose, or change pain medications.

- Health care providers may prescribe medications to prevent or treat stress gastritis in a patient who is critically ill or injured. Medications to protect the stomach lining include sucralfate (Carafate), H2 blockers, and PPIs. Treating the underlying illness or injury most often cures stress gastritis.

- Health care providers may treat people with pernicious anemia due to autoimmune atrophic gastritis with vitamin B12 injections (parenteral 1000 micrograms or oral 1000 to 2000 micrograms). Monitor iron and folate levels, and eradicate any co-infection with Helicobacter pylori. Endoscopic surveillance for cancer risk and gastric neuroendocrine tumors is required 12.

Acute gastritis prognosis

The outlook depends on the cause, but is often very good. The mortality and morbidity is dependent on the cause of the gastritis. Generally, most cases of gastritis are treatable once the cause is determined. The exception to this is phlegmonous gastritis, which has a mortality rate of 65%, even with treatment.

References- Coati I, Fassan M, Farinati F, Graham DY, Genta RM, Rugge M. Autoimmune gastritis: Pathologist’s viewpoint. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015 Nov 14;21(42):12179-89.

- Azer SA, Akhondi H. Gastritis. [Updated 2019 Jun 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544250

- Nayak VH, Engin NY, Burns JJ, Ameta P. Hypereosinophilic Syndrome With Eosinophilic Gastritis. Glob Pediatr Health. 2017;4:2333794X17705239

- Sipponen P, Maaroos HI. Chronic gastritis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2015 Jun;50(6):657-67.

- Lambrecht NW. Ménétrier’s disease of the stomach: a clinical challenge. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011 Dec;13(6):513-7.

- Neumann WL, Coss E, Rugge M, Genta RM. Autoimmune atrophic gastritis–pathogenesis, pathology and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Sep;10(9):529-41.

- Hershko C, Ianculovich M, Souroujon M. A hematologist’s view of unexplained iron deficiency anemia in males: impact of Helicobacter pylori eradication. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2007 Jan-Feb;38(1):45-53.

- Rodriguez-Castro KI, Franceschi M, Miraglia C, Russo M, Nouvenne A, Leandro G, Meschi T, De’ Angelis GL, Di Mario F. Autoimmune diseases in autoimmune atrophic gastritis. Acta Biomed. 2018 Dec 17;89(8-S):100-103.

- Venerito M, Varbanova M, Röhl FW, Reinhold D, Frauenschläger K, Jechorek D, Weigt J, Link A, Malfertheiner P. Oxyntic gastric atrophy in Helicobacter pylori gastritis is distinct from autoimmune gastritis. J. Clin. Pathol. 2016 Aug;69(8):677-85.

- di Mario F, Cavallaro LG. Non-invasive tests in gastric diseases. Dig Liver Dis. 2008 Jul;40(7):523-30.

- Yang JC, Lu CW, Lin CJ. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: current status and future concepts. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014 May 14;20(18):5283-93.

- Chen WC, Warner RRP, Harpaz N, Zhu H, Roayaie S, Kim MK. Gastric Neuroendocrine Tumor and Duodenal Gastrinoma With Chronic Autoimmune Atrophic Gastritis. Pancreas. 2019 Jan;48(1):131-134.