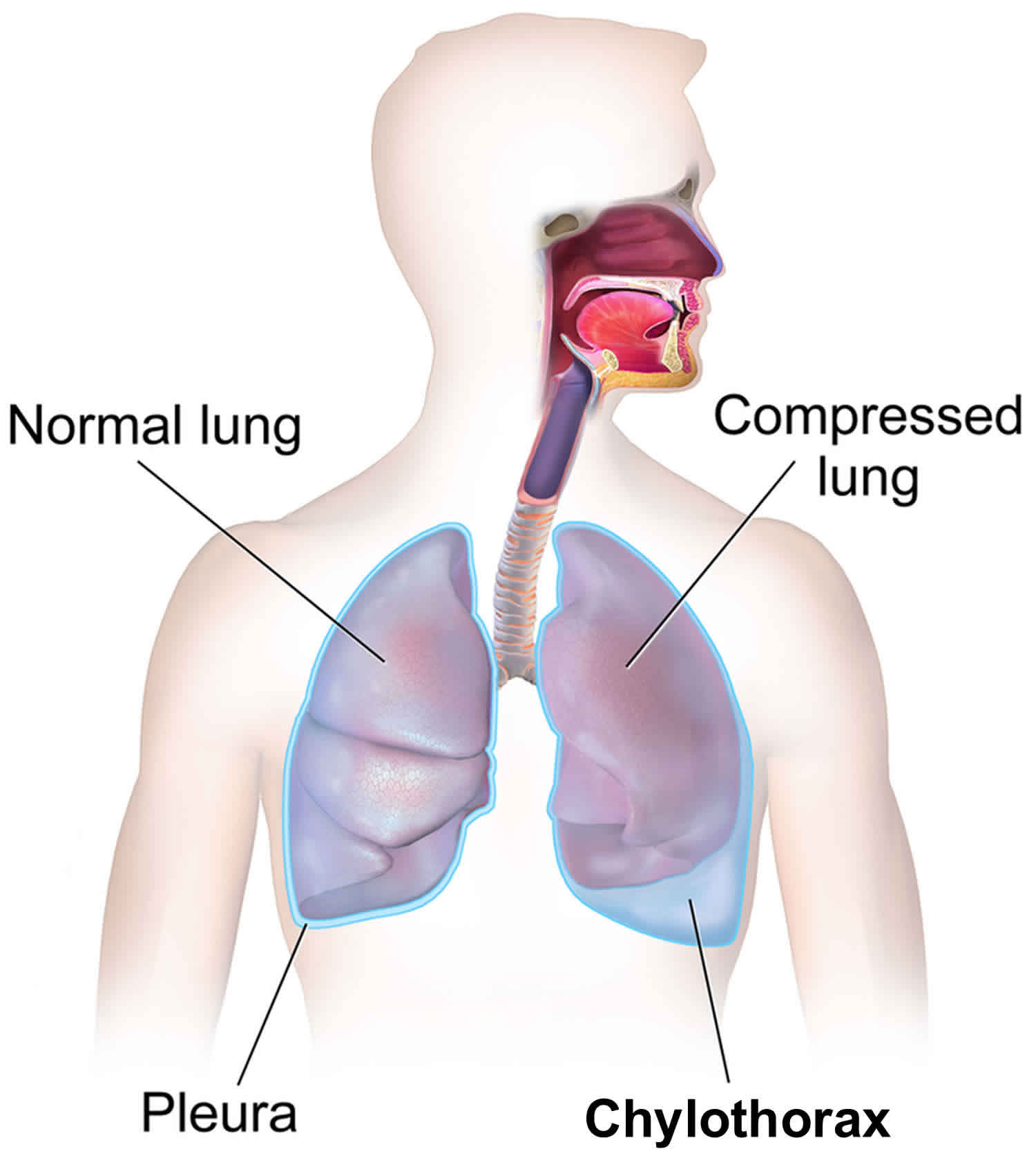

Chylothorax

Chylothorax is the accumulation of chyle or lymphatic fluid in the pleural cavity around the lungs due to damage to the thoracic duct 1. Chylothorax can be seen in many conditions and trauma and cancer are the leading causes. This is a rare condition that may develop as a complication of thoracic and esophageal and thoracic surgery and hematologic malignancies. Chylothorax has no predilection for gender or age. The prevalence of after various cardiothoracic surgeries is 0.2% to 1%. Mortality and morbidity rates are approximately 10%. The diagnosis based on pleural fluid can be made by demonstration of triglycerides of more than 110 mg/dL or presence of chylomicrons. Various surgical and nonsurgical management strategies can be used for the treatment of chylothorax. Initially the treatment is conservative but if the leak does not stop, surgery is required. New surgical techniques like pleurovenous or pleuroperitoneal shunting and thoracic duct embolization have been used with success. Currently, somatostatin analogs are effectively used for its treatment.

Chyle is made primarily of chylomicrons, an aggregate of long-chain triglycerides, cholesterol esters, and phospholipids. It is also rich in lymphocytes, primarily T lymphocytes as the major cellular component with concentrations that range from 400 to 6800 cells. Chyle as similar electrolyte concentration plasma but is rich in immunoglobulins with fat-soluble vitamins. As the normal chyle production is around 2.4 liters per day, a considerable amount of chyle can accumulate in the pleural cavity in a very short period.

Chyle is the milky bodily fluid formed in the lacteal system of the intestine. The small and medium chain triglycerides consumed in the diet are easily broken to free fatty acids by the intestinal enzymes and readily absorbed into the portal circulation. However, the large molecules of complex long-chain triglycerides cannot be broken down by the intestinal lipases. They combine with phospholipids, cholesterol and cholesterol esters to form chylomicrons in the jejunum. These large molecules then get absorbed into the lymphatic system of the small intestine to form the chyle. The lymphatic drainage system of intestine will be joined by the lymphatic drainage from the lower extremities to form the thoracic duct system which ultimately drains in the system circulation. If there is the breach of the integrity of thoracic duct, the milky lipid-rich chyle leaks to the surrounding structures.

Pseudo-chylothorax or chyliform effusion

Effusions with the gross appearance similar to chylothorax, milky white are called as pseudo-chylothorax. These are less common than the classical chylothorax and have been reported being in long-standing exudate pleural effusion of various cause. They contain a high concentration of cholesterol, giving them that characteristic milky or white appearance. In long-standing exudative pleural effusion, the cell undergoes slices releasing the cholesterol from the cell membrane into the fluid which gets trapped in the pleural cavity. However, unlike classical chylothorax, they do not contain chylomicrons or long chain fatty acids. Pseudo- chylothorax is commonly associated with tuberculosis and chronic rheumatoid pleural effusion due to the high cell concentration. Other causes described and literature are yellow nail syndrome and paragonimiasis. The cholesterol concentration in pseudo-chylothorax is typically more than 200 mg; triglycerides level is less than 110 mg/dL and cholesterol to triglycerides ratio is always more than 1. Cholesterol crystals may be visible in dried slides from pleural fluid when viewed under polarized light and appear as rectangle plates with notched edges. The presence of cholesterol crystals is virtually diagnostic of pseudo-chylothorax.

What is the thoracic duct

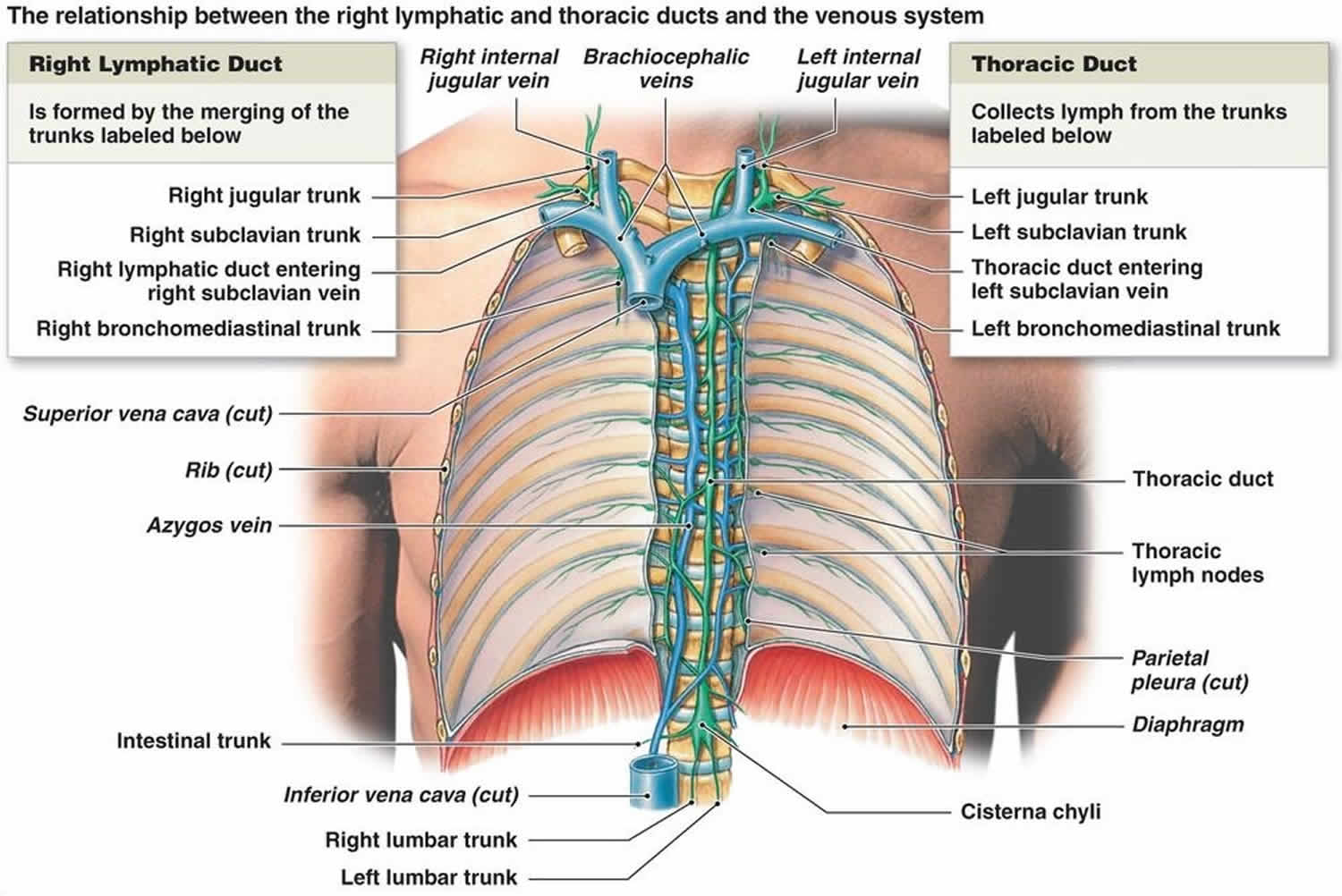

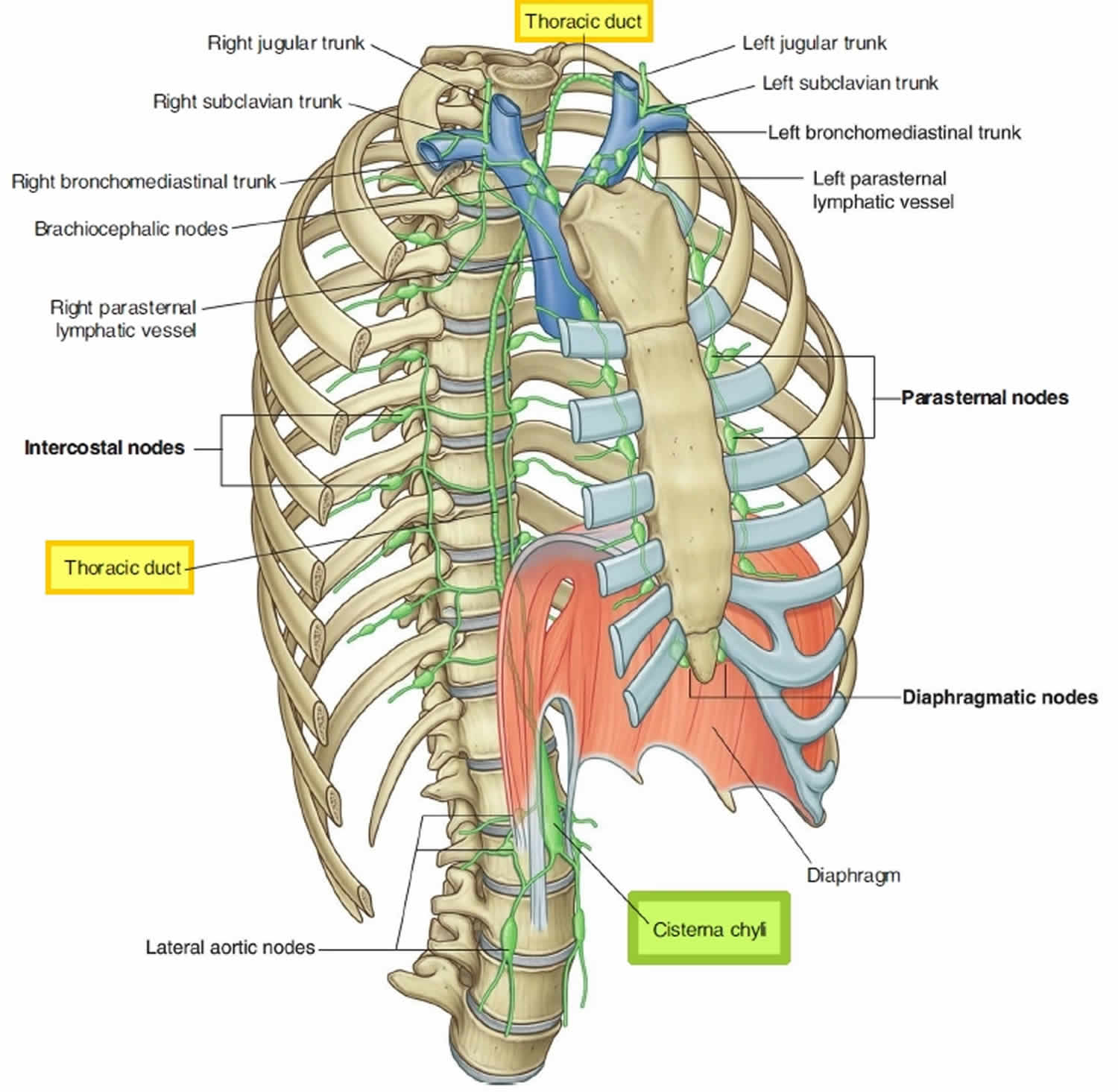

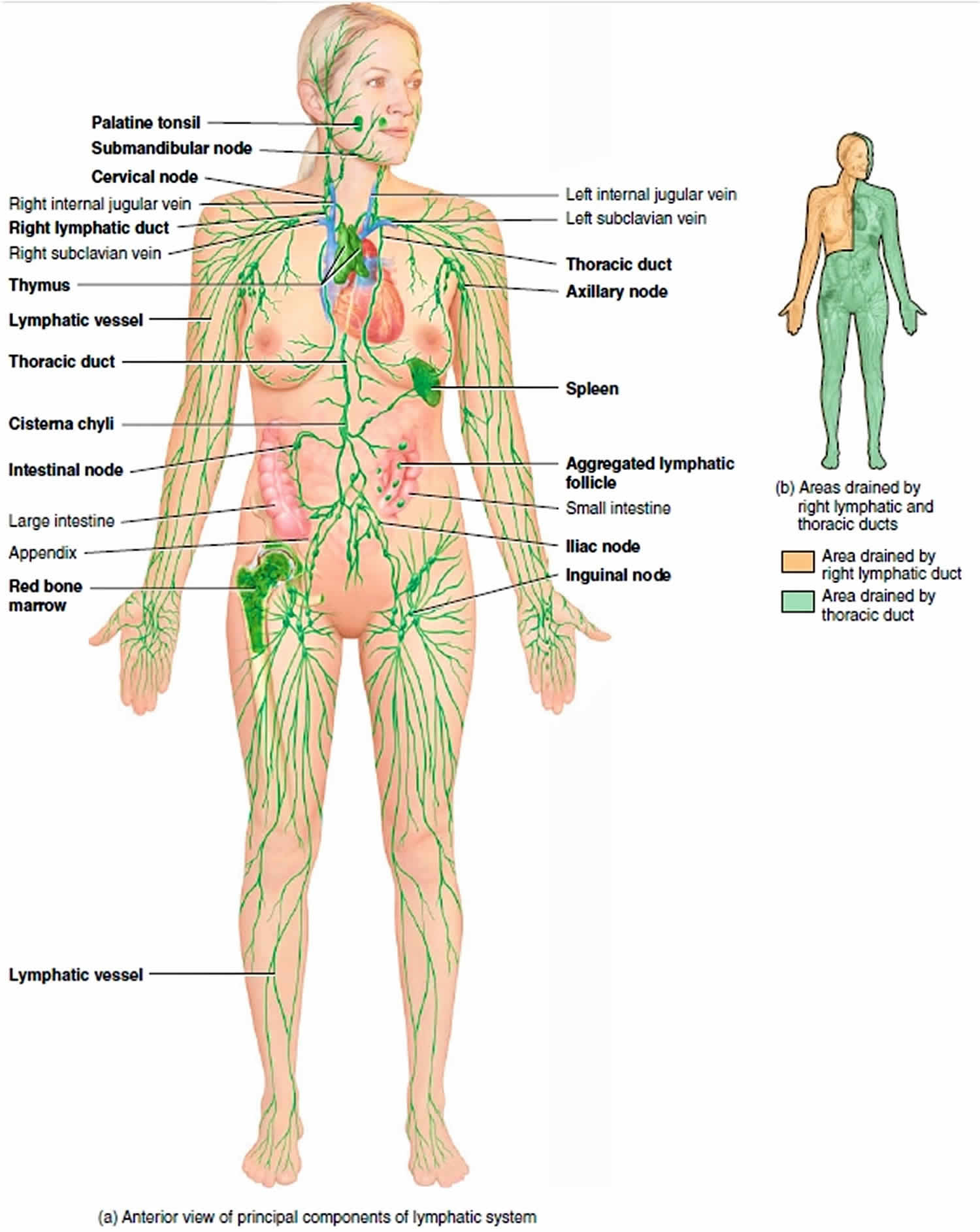

The thoracic duct is the main lymphatic channel for the return of chyle to the venous system. The thoracic duct drains lymph from both lower limbs, abdomen (except the convex area of the liver), left hemithorax, left upper limb and left face and neck. The thoracic duct is present in all individuals. The thoracic duct most inferior part, located at the union of the lumbar and intestinal trunks, is the cisterna chyli which lies on the bodies of vertebrae L1 and L2 (range T10-L3) (Figure 1). From there, the thoracic duct ascends along the vertebral bodies. In the superior thorax, the thoracic duct turns left and empties into the venous circulation at the junction of the left internal jugular and left subclavian veins. The thoracic duct is often joined by the left jugular, subclavian, and/or bronchomediastinal trunks just before it joins with the venous circulation. Alternatively, any or all of these three lymph trunks can empty separately into the nearby veins. When it is joined by the three trunks, the thoracic duct drains three-quarters of the body: the left side of the head, neck, and thorax; the left upper limb; and the body’s entire lower half (see Figure 2).

After leaving the lymph nodes, the largest collecting lymphatic vessels converge to form lymph trunks. The lymph trunks drain into the largest lymphatic vessels, the lymph ducts (Figures 1 and 2). Whereas some individuals have two lymph ducts, others have just one. Lymphatic ducts empty lymph fluid into the venous system. The two lymphatic ducts of the body are the right lymphatic duct and the thoracic duct. The thoracic duct is the larger of the two and responsible for lymph drainage from the entire body except for the right sides of the head and neck, the right side of the thorax, and the right upper extremity which are primarily drained by the right lymphatic duct (see Figure 2) 2.

Where does the thoracic duct drain?

The thoracic duct delivers lymph into junction between left subclavian and left internal jugular veins.

Right lymphatic duct delivers lymph into junction between right subclavian and right internal jugular veins.

Figure 2. Thoracic duct drainage

Chylothorax causes

The cause of chylothorax can be classified into three broad categories, spontaneous (non-traumatic), traumatic, and idiopathic. Historically, non-traumatic chylothorax was the more common cause for chylothorax accounting for two-thirds of all cases. Recently, traumatic chylothorax, particularly postoperative chylothorax, accounts for more than 50% of all cases described in the literature 3.

Non-traumatic chylothorax can be due to the following:

- Congenital chylothorax can be seen as an isolated condition or in association with other lymphatic abnormalities like lymphangiectasis, lymphangiomatosis, tuberous sclerosis, congenital heart disease, or chromosomal abnormalities such as trisomy 21 or Turner syndrome.

- Neoplastic chylothorax is the most common cause of non-traumatic chylothorax. Various cancers like lymphoma, chronic lymphoid leukemia, lung cancer, esophageal cancer or metastatic carcinoma have been implicated in chylothorax. Interestingly, there is a relative decrease in the incidence of chylothorax in patients with lymphoma in the recent time. This is likely due to early diagnosis and treatment of lymphoma avoiding the late complication of chylothorax.

- Infectious chylothorax is mostly seen in developing countries as a complication of tuberculous lymphadenitis. Other infections known to cause chylothorax are aortitis, histoplasmosis, and filariasis.

- Rare causes of chylothorax reported in the literature are due to cattleman disease, sarcoidosis, Kaposi sarcoma, yellow nail syndrome, Noonan syndrome, Down syndrome, Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, macroglobulinemia, amyloidosis, venous thrombosis, thoracic radiation, goiter. All these reported diseases will lead to obstruction or destruction of thoracic duct causing chylothorax. Even parental nutrition therapy is implicated in chylothorax. Rapid infusion of total parenteral nutrition containing a high concentration of triglycerides can overwhelm the draining capacity of the thoracic duct leading to leakage of chyle to this surrounding pleural space and cause chylothorax.

Traumatic chylothorax occurs due to disruption of thoracic duct anywhere in its course in the mediastinum. They can occur as a complication of the surgical procedure or can follow blunt or penetrating trauma to the chest.

- Post-operative chylothorax constitutes the most common cause of chylothorax in the modern medicine. The risk of postoperative chylothorax depends on the type of surgery done. Esophagostomy carries the highest risk of 5% to 10% postoperative chylothorax, followed by lung resection with mediastinal lymph node dissection with 3% to 7% risk. Other surgeries like mediastinal tumor resection, thoracic aneurysm repair, sympathectomy, any surgeries in the lower neck and mediastinum carry a risk of chylothorax. Ingestion of milk before the surgery can lead to better visualization of the thoracic duct in the surgical field by causing whitish discoloration of the thoracic duct. It is proposed on of the preoperative steps to prevent postoperative chylothorax, although this has not been formally studied. Nonsurgical posttraumatic chylothorax is also described after central line placement, pacemaker implantation, embolization of the pulmonary arteriovenous malformation.

- Blunt trauma to the chest or thoracic spine can disrupt the thoracic duct without any obvious injury to the surrounding structure leading to chylothorax. Chylothorax is also described after blasting injuries. Chylothorax is also described following a trivial injury like coughing and sneezing.

- Penetrating injuries of the chest like gunshot injury and stab injury can directly damage the thoracic duct leading to chylothorax

Idiopathic causes account for nearly 10% of all cases of chylothorax. Chylothorax is considered to be idiopathic after extensive investigation does not reveal any known cause for it. Most of these idiopathic cases are related to undiagnosed malignancy.

Chylothorax symptoms

The clinical features of chylothorax depend upon the cause. Small chylothorax can be asymptomatic and is detected incidentally. Patient with large chylothorax usually presents with signs and symptoms caused by the mechanical effect of compression on lung expansion. Progressive breathlessness decreases exercise capacity; chest pressure is common presenting complaints. Fever and chest pain are usually absent. The patient can accumulate a large amount of chylothorax without any complaints if the fluid recommendation is gradual and respiratory system gets acclimatized to it. Post-traumatic chylothorax can present up to 10 days after the inciting trauma. In the post-surgical patient’s, the chylothorax me the first detected as a pleural effusion or by persistent drainage from the indwelling chest tubes.

Chylothorax symptoms may include:

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea)

- Fast breathing (tachypnea)

- Symptoms of pleural effusion:

- Chest pain, usually a sharp pain that is worse with cough or deep breaths

- Cough

- Fever and chills

- Hiccups

- Rapid breathing

- Shortness of breath

On physical examination, findings of decreased breath sounds and dullness to percussion may be present depending on the size and location of fluid. Eighty percent of chylothorax cases are unilateral. Due to the location of the thoracic duct, the right side is more common than the left, accounting for two-thirds of the total cases.

Chylothorax diagnosis

Further evaluation of chylothorax depends on the suspected cause and the availability of resources.

- Chest x-ray: Chest radiographs routinely done to evaluate dyspnea, particularly in postoperative and traumatic patients can detect unilateral pleural effusion. Chylothorax appears as homogenous density obligating the costophrenic and cardio phrenic angle. A routine chest x-ray cannot differentiate chylothorax from other causes of pleural effusion.

- Thoracic ultrasound: Ultrasound is being increased used for the evaluation of patients with pleuropulmonary pathology. Like other effusion, it appears as an isodense echoic region without any septation or loculation. However, ultrasound cannot differentiate chylothorax from other causes of pleural effusion.

- Chest CT scan: CT scan is more sensitive than chest x-ray and ultrasound for the diagnosis of chylothorax. Routine CT chest can show cisterna chyli in around 2% of cases. Due to the high amount of fat content, it is seen as a low-attenuation tubular area in the posterior mediastinum. CT scan also may show the cause of chylothorax like mass lesions or obstructive lesion in the posterior mediastinum, thoracic malignancy, or evidence of trauma.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): MRI of the chest can show cisterna chyli in 100% of the cases and can be used for better evaluation of chylothorax. However, as MRI of the chest is not an optimal investigation for the thoracic pathology, it is rarely used in clinical practice.

- Conventional lymphangiography: Lymphangiography is a technique used to delineate lymphatic system. In the modern medicine, this test is rarely used due to the availability of less invasive alternatives which are equally precise. In this technique dye like methylene blue that stains the lymphatics is injected into the web spaces between the toes. A longitudinal or transverse cutaneous incision at the base of the first metatarsal bone is made to expose a lymphatic vessel with blue staining after dissection of the surrounding tissue. The isolated lymphatic vessel is then cannulated using a 30 gauge needle. After accessing the lymphatic vessel, 10 mL of Lipiodol is slowly injected at the rate of 0.2 mL/min to 0.4 mL/min. Serial fluoroscopic spot images are obtained upwardly every 5 to 10 minutes over the course of the injected Lipiodol. If Lipiodol does not reach the area of interest, normal saline at the same rate can be injected to push Lipiodol further into the area of interest. This can reliably show any leakage in the thoracic duct leading to chylothorax. A further modification of this called nodal lymphangiogram has been developed in the recent time. A targeted lymph node is selected, and ethiolised oil is injected into the cortex of the lymph node at a rate 1 ml per min for total 10 ml. Serial spot radiographs of the pelvis, abdomen, and thorax are then acquired to follow the progression of the dye. This Intranodal lymphoscintigraphy is sensitive, technically easier and also has fewer complications. Lymphogram can be therapeutic in up to 40% of cases. The high-density oil used in the procedure can close in leak during the procedure.

- Nuclear Lymphoscintigraphy: This technique has been used more commonly than the traditional lymphangiography to delineate lymphatic system. In this procedure, Tc99m labeled human diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (HAS-DTPA) is injected to the subcutaneous lesions of the dorsum of the foot bilaterally. Sequentially anterior and posterior images of the chest are obtained using a gamma camera to identify the leak. This technique can be combined integrated low-dose CT scan with single-photon emission computed tomography combined to get the more accurate SPECT/CT images. Radio nuclear localization using lymphoscintigraphy has been shown to correlate with traditional lymphangiography and surgical localization of leak.

Laboratory testing

Thoracentesis and analysis of the fluid is the diagnostic study of choice for chylothorax: All fluid samples should be sent for white blood cell count, differential, glucose, Lactic dehydrogenase, total protein level, cytology, microbiology smear, and culture. If chylothorax is suspected based on the color of the fluid, then additional tests like Ph, total triglycerides levels, and cholesterol levels should be sent.

- Color: Based on the amount of fat content in chylothorax, the appearance of fluid can (white) milky, serous or serosanguineous. The absence of milky appearance does not exclude a chylothorax. If the fluid is kept undisturbed for some time on centrifugation, the supernatant of fluid is clear. In empyema, the supernatant is not clear.

- Cell counts: Chyle is rick in lymphocytes accounting for 80% of all the cells. The lymphocytes are predominately polyclonal population of T cells.

- Lipid analysis: Measurement of the pleural fluid triglyceride content is key to the diagnosis of suspected chylothorax. Unlike in any other body fluids, chylothorax is very rich in large chain fatty acids absorbed from the small intestine. The pleural fluid triglyceride concentration greater than 110 mg/dL confirms the diagnosis of chylothorax. However, 15% of chylothorax are known to have triglyceride concentration less than 110 mg depending on the time of last meal and the fat content of the diet. If clinical suspicion of chylothorax is high, then lipid electrophoresis of the pleural fluid should be done. Detection of chylomicrons in the pleural fluid by lipoprotein electrophoresis confirms chylothorax. Typically, the total cholesterol level in a chylothorax is less than 200 mg/dl.

- Others compositions: The other fluid composition is similar to plasma. Chylothorax is usually alkaline with pH from ranging from 7.4 to 7.8.

Chylothorax treatment

The appropriate management of chylothorax depends on the cause and includes one or more of many interventions like dietary modification, pleurodesis, and thoracic duct ligation. Recently, the use of somatostatin/octreotide, midodrine and sirolimus to prevent chyle formation has been used. New surgical techniques like pleurovenous or pleuroperitoneal shunting and thoracic duct embolization have been used with success. Most patients benefit from a staged care plan from least invasive options to more invasive techniques 4, 5.

Dietary therapy

As chylous fluid is formed the long chain fatty acids; decreasing or eliminating these fatty acids from the diet will lead to decreased chyle drainage spontaneously closure of leak. Diet with less than 5 kcal of fat per meal is used in this technique. This can effectively reduce chyle formation, but over long periods, it will lead to fat deficiency and malnutrition. In fact, venous fat hemorrhage can remedy some of the shortcomings of this therapy. Small chain and medium chain fatty acids can be provided in a diet, and long chain fatty acids can be supplemented through intravenously.

Thoracentesis

Intermittent therapeutic thoracentesis or use of an indwelling catheter for home drainage is typically used in the initial management of non-traumatic and nonsurgical traumatic effusions to relieve dyspnea caused by the pleural fluid. This technique can be effectively used if there is a gradual recommendation of her pleural fluid. A chest tube can be used in postsurgical chylothorax. Prolonged drainage of pleural fluid comes with risk of significant malnutrition and loss immunoglobulins putting the patient at risk of infections. Hence continuous pleural fluid drainage should typically be restricted to less than 2 weeks. Surgical intervention is recommended if the pleural fluid drainage exceeds 1.5 L per day.

Pleurodesis

This should be reserved for patients who continue to reaccumulate fluid despite dietary modification and repeated thoracenteses. Pleurodesis can be accomplished by tall installation of a chest tube drainage by video-assisted thoracic surgery with talc insufflation. In some cases, this procedure can remedy up to 80% of chylothorax. Concomitant ligation of the thoracic duct to prevent further chyle formation during surgical pleurodesis is also done with high success.

Thoracic duct ligation

This invasive procedure is done using video-assisted thoracic surgery and can be useful in patients where dietary modification and pleurodesis has failed. Lymphedema is a known complication of thoracic duct ligation but usually, resolves after several months due to collateral lymphatic venous communications.

Thoracic duct embolization and disruption

Percutaneous catheterization and embolization are needle disruption of the thoracic duct and cisterna chyli along with prominent retroperitoneal lymphatic ducts have been used increasingly in both traumatic and nontraumatic chylothorax. Initial pedal lymphangiogram follows fluoroscopic visualization of the large retroperitoneal lymphatics, which has been accessed by transabdominal percutaneous needle cannulation. After cannulation of the cisterna chyli, the catheter is advanced with thoracic duct installation of contrast to localize the leak. The affected thoracic segment is then embolized with coils and surgical clue.

Emerging therapies

Somatostatin and octreotide can decrease the gastric, pancreatic, and biliary secretions and reduce the total flow of gastric lymphatics. Because the reduction chyle formation and flow rates, they can spontaneously remedy the leak in thoracic duct. This technique is reported to be useful in many cases of spontaneous chylothorax, congenital chylothorax, postoperative chylothorax and chylothorax due to malignancy. The optimal dose and duration of treatment is not clear.

Sirolimus used for the effect to treatment of lymphangiomyomatosis is also known to decrease the incidence of chylothorax in these set of patients.

Pleuroperitoneal or pleural venous shunt. Shunting of chylous pleural fluid into the venous system or peritoneal cavity can also resolve chylothorax. Two types of pleuroperitoneal shunts are available. Denver pleuroperitoneal shunt is an active pump which requires manual pumping and Le Veen pleuroperitoneal shunt is a passive pump. The main advantage of the shunt procedure is the recycling of the nutritionally rich chyle to the body. Pleural venous shunting of chylous fluid from the pleural space to the subclavian jugular vein has been performed successfully in patients with yellow nail syndrome and postsurgical chylothorax.

Chylothorax prognosis

The prognosis in chylothorax varies in accordance with the condition’s underlying cause. Overall, the outcome for chylothorax from benign causes is good but in cases of cancer, the outcomes are poor 6.

References- Rudrappa M, Paul M. Chylothorax. [Updated 2019 May 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459206

- Rizvi S, Law MA. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jan 25, 2019. Anatomy, Thorax, Mediastinum Superior and Great Vessels.

- Hayashi K, Hanaoka J, Ohshio Y, Igarashi T. Chylothorax secondary to a pleuroperitoneal communication and chylous ascites after pancreatic resection. J Surg Case Rep. 2019 Jan;2019(1):rjy364

- Pospiskova J, Smolej L, Belada D, Simkovic M, Motyckova M, Sykorova A, Stepankova P, Zak P. Experiences in the treatment of refractory chylothorax associated with lymphoproliferative disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019 Jan 09;14(1):9.

- Papoulidis P, Vidanapathirana P, Dunning J. Chylothorax, new insights in treatment. J Thorac Dis. 2018 Nov;10(Suppl 33):S3976-S3977

- Costa KM, Saxena AK. Surgical chylothorax in neonates: management and outcomes. World J Pediatr. 2018 Apr;14(2):110-115.