What is adenomyosis

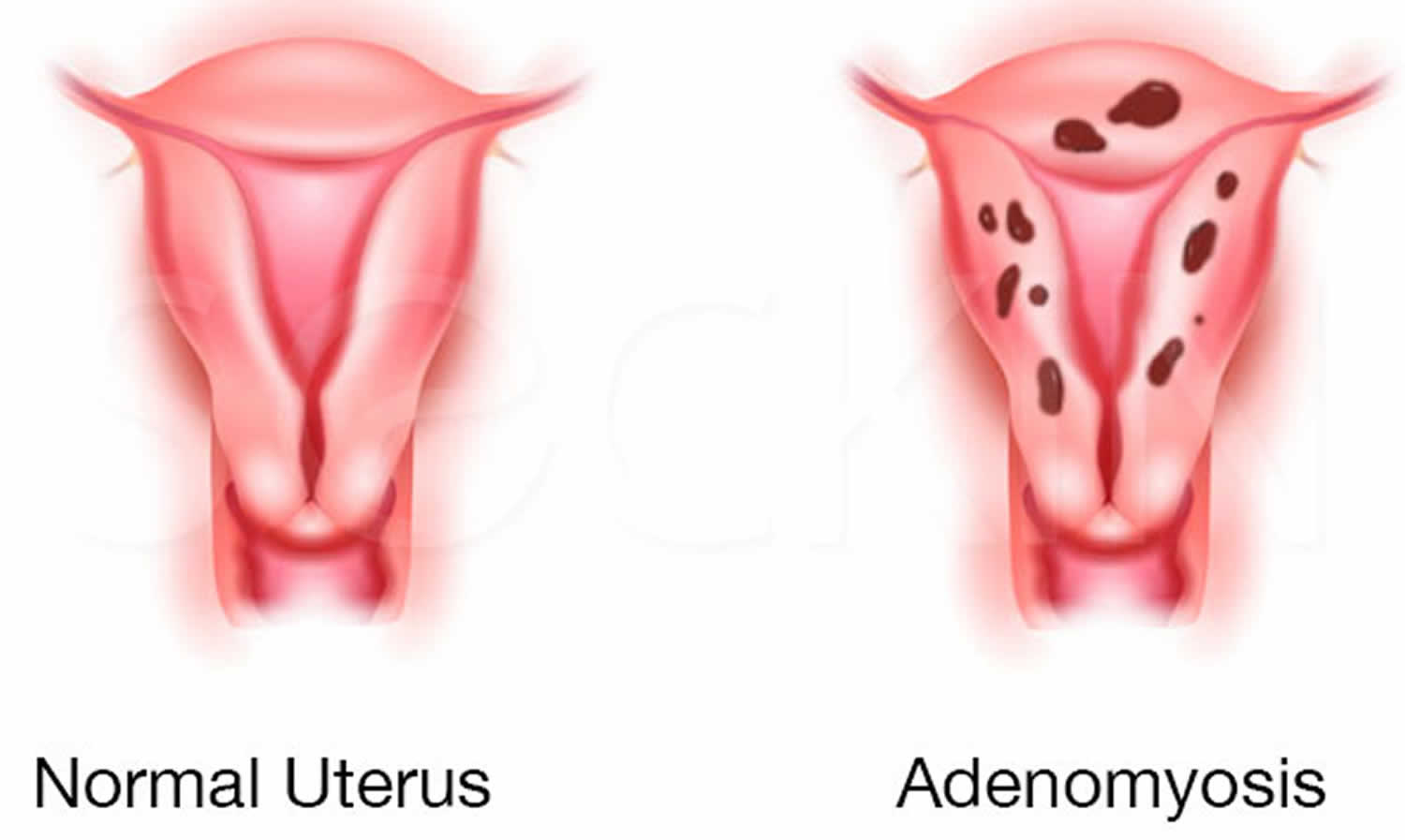

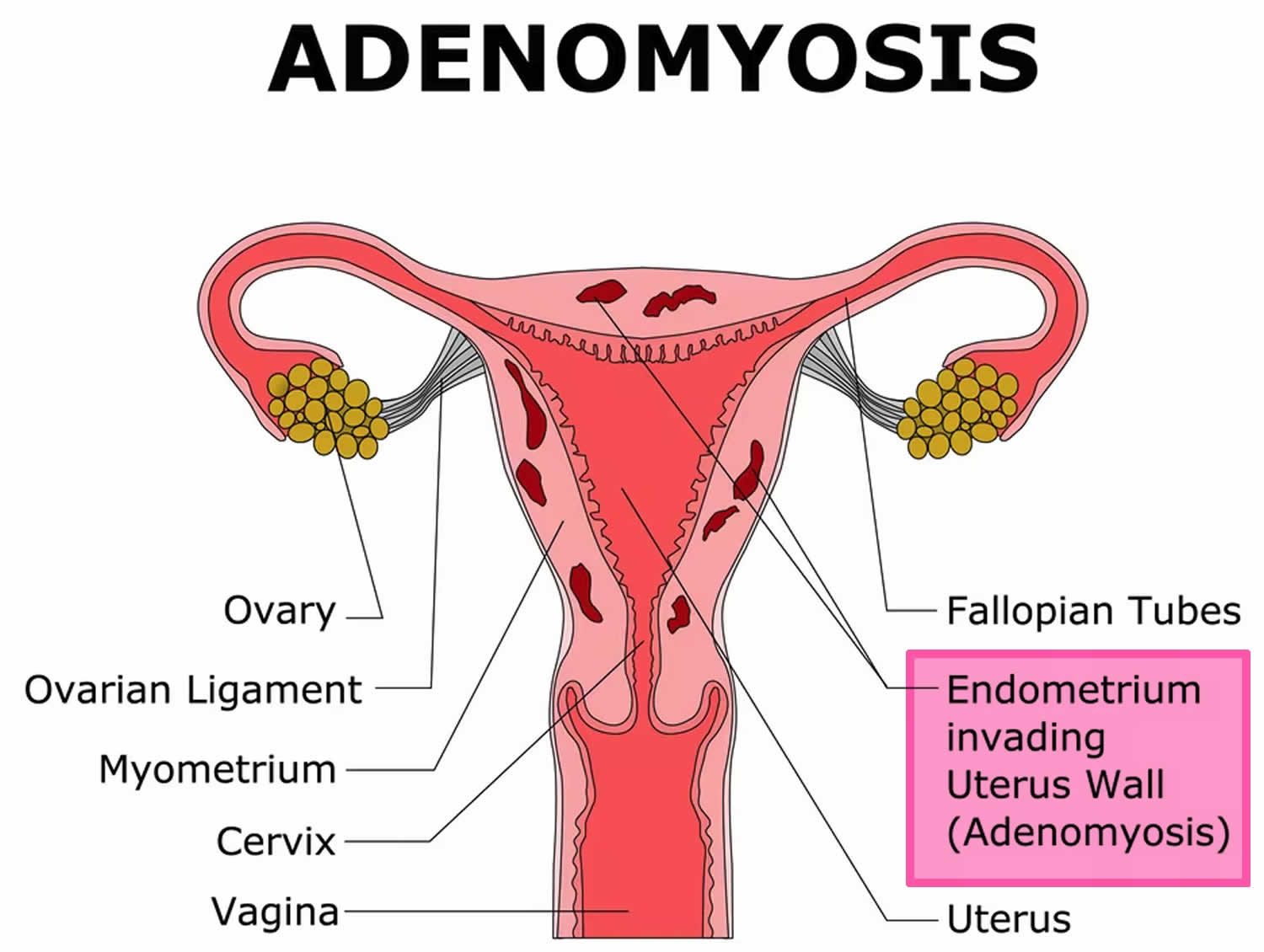

Adenomyosis also called uterine adenomyosis, is a common, benign uterine pathology that occurs when the cells that normally line the uterus (endometrial tissue) also grow into the layer of muscle in the wall (the myometrium) of your uterus. The area of the uterus affected by adenomyosis is known as the endometrial-myometrial junction, which is where the endometrium and the myometrium (the muscular part of the uterus) meet (see Figure 1 and 2). Adenomyosis is thought by many to be on the spectrum of endometriosis, with ectopic endometrial tissue in the myometrium 1. The displaced endometrial tissue continues to act normally — thickening, breaking down and bleeding — during each menstrual cycle. An enlarged uterus and painful, heavy periods can result. Adenomyosis can either be quite spread out, known as generalized adenomyosis or localized in one place. If adenomyosis is concentrated in one area, it can lead to a mass called an adenomyoma.

Adenomyosis may present with abnormally heavy uterine bleeding (menorrhagia) and painful periods or menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea) or infertility 2.

Adenomyosis may affect 20% to 65% of females; however, many women aren’t aware they have adenomyosis because adenomyosis doesn’t always cause symptoms 3. Scientists don’t currently know why some women with adenomyosis have symptoms and others don’t. Furthermore, adenomyosis is often found in women with other conditions like leiomyoma (50%), endometriosis (11%), and endometrial polyps (7%), it’s difficult to determine which condition caused your symptoms 4. But those who have symptoms typically report painful, heavy, or prolonged menstrual bleeding. Examination may reveal a dense, enlarged uterus.

Experts don’t know why some people develop adenomyosis. Adenomyosis is more common in women who have had children. There is an association between the presence of adenomyosis and the number of times a women has given birth: the more pregnancies, the more likely you are to have adenomyosis. Women with adenomyosis have also often had a trauma to the uterus such as surgery in the uterus, like during a caesarean section.

A rare form of adenomyosis, termed juvenile cystic adenomyosis, is characterized by more extensive hemorrhage (bleeding) within myometrial cysts and is typically seen in women younger than 30. Symptoms are typically refractory to medical therapy and require surgery, either myomectomy or hysterectomy 5.

Adenomyosis may be difficult to diagnose. Transvaginal ultrasound (the ultrasound probe is placed in the vagina) and MRI are imaging modalities that may show characteristic findings. The test should preferably be performed by a gynecologist who specializes in ultrasound, as general ultrasonagraphers may be inexperienced in the diagnosis of adenomyosis. Unfortunately, the sonographic features of adenomyosis are variable and may be absent 6. The reported sensitivity and specificity of transabdominal ultrasound are 32-63% and 95-97% respectively 7. However, it has been reported that transvaginal ultrasound is as sensitive (89%) and specific (89%) as MRI in diagnosing adenomyosis. Ultrasound features of adenomyosis, including asymmetrical uterine wall thickening anteriorly with focal heterogeneity and associated increased blood flow, as well as the “venetian blind” pattern of acoustic shadowing. The latter may be seen with either adenomyosis or uterine fibroids 8. However, the only way to confirm adenomyosis is to examine the uterus after hysterectomy.

Imaging features of adenomyosis are variable and in many instances very subtle. Three (some say four) forms can be distinguished 6:

- Diffuse adenomyosis is the most common of uterine adenomyosis 9. Diffuse adenomyosis may account for about 2/3rd of uterine adenomyosis. Diffuse adenomyosis can be even or uneven in involvement and, therefore, it is subclassified as either symmetrical or asymmetrical 10.

- Focal adenomyosis and adenomyoma: some consider these as the same. Focal adenomyosis most commonly occurs at the fundal endometrial-myometrial interface 11.

- Cystic adenomyosis is a rare variant of adenomyosis and is believed to the result of repeated focal hemorrhages resulting in cystic spaces filled with altered blood products 12.

- Adenomyotic cyst is an extremely rare variation of cystic adenomyosis 13. The lesion consists of a large hemorrhagic cyst, which is partly or entirely surrounded by a solid wall. It can be entirely within the myometrium, submucosal, or subserosal and frequently is associated with symptoms of menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea.

Adenomyosis association with other gynecological disorders

Coexistence of adenomyosis with other gynecological disorders, such as myomas and endometriosis, has been well established 14.

- If you have adenomyosis, you might have co-existent endometriosis, which has been reported in 27% of women with endometriosis 15. A study evaluating the prevalence of adenomyosis using MRI scans in women diagnosed with endometriosis as compared to two control groups, one without endometriosis, defined as control group, and another without endometriosis but with a partner considered hypofertile, defined as healthy control group, confirmed the presence of adenomyotic lesions, in 79% of the endometriosis group, 28% of the control group, and 9% in the healthy control group 16. Interestingly, the prevalence of adenomyosis reached 90% in the subset of women with endometriosis less than 36 years of age. This study contrasts findings from a previous study, in which adenomyosis diagnosed with MRI was present in only 27% of women with endometriosis 15.

- Leiomyomas: may be present in almost 50% of cases involving adenomyosis of the uterus 17.

- Other reported associations include endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial polyps 17.

The cause of adenomyosis remains unknown, but adenomyosis is only seen in women in their reproductive years because it requires the hormone estrogen to grow. Adenomyosis eventually goes away after menopause when estrogen production drops.

Adenomyosis is difficult to treat and it will disappear after menopause so management will depend on your life stage. For women who have severe discomfort from adenomyosis, hormonal treatments and anti-inflammatory pain medications can help. Hormonal treatments focus on suppressing your menstruation. This can be achieved by combined estrogen and progesterone therapy (such as the combined oral contraceptive pill), progestogen-only treatment (such as a Mirena) or placing women into an “induced” menopause (through GnRH analogs).

Surgical treatment is most effective when the adenomyosis is localized to a smaller area and can be removed, and this type of surgery doesn’t prevent women falling pregnant in the future. If the adenomyosis is spread throughout a larger area then treatments include destroying the lining of the uterus (endometrial ablation) provided adenomyosis is not too deep, and hysterectomy (surgery to remove a woman’s uterus), both of which will prevent further pregnancy. Removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) cures adenomyosis.

Other treatment options are interventional radiology such as uterine artery embolisation, where the blood supply to the uterus is cut off and magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound where the adenomyosis is destroyed with ultrasound energy.

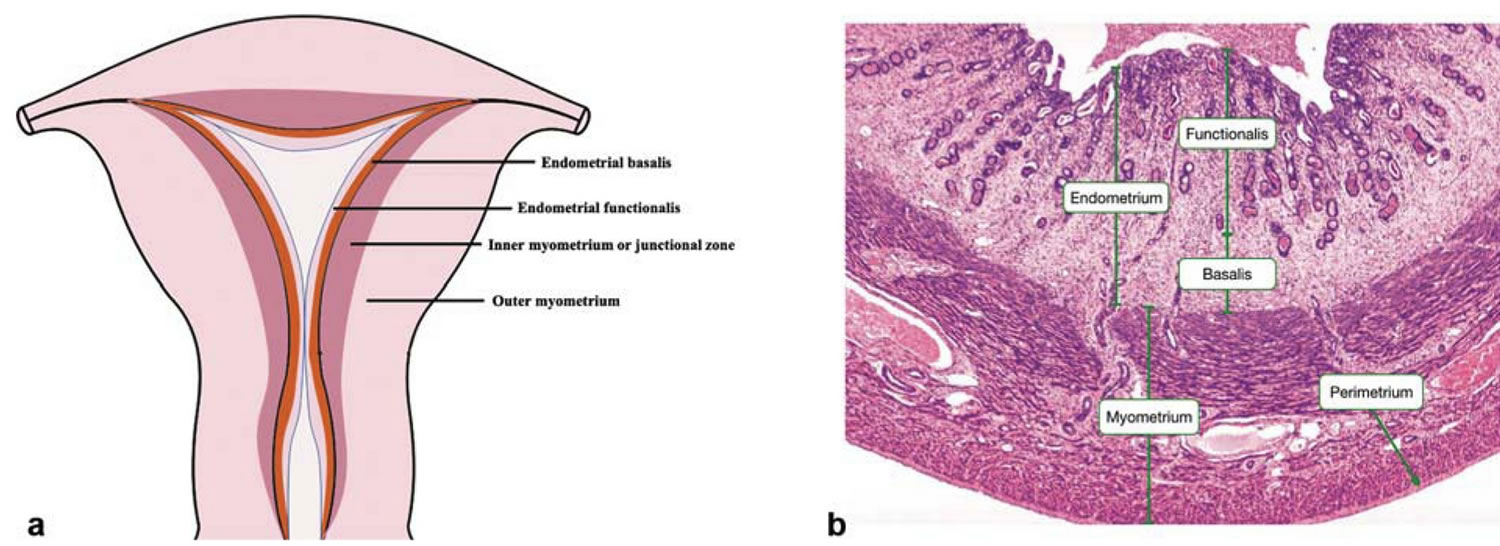

Figure 1. Uterus anatomy

Figure 2. Structure of normal uterus

Footnotes: (a) The coronal section of normal uterus. (b) Hematoxylin–eosin staining of the full-thickness of uterus. The myometrium resides between the endometrium and uterine serosa and is composed of an outer longitudinal layer and an inner circular layer of smooth muscle cells and supporting stromal and vascular tissue. Histologically, the endometrial-myometrial interface is a mucosal-muscular interface without an intervening basement membrane, differing markedly from other mucosal tissues (e.g., intestine) 18. Recently, a subendometrial layer of the myometrium, called the “inner myometrium” (1a), has been identified mainly by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 19. MRI reveals that the uterine wall is composed of high-signal intensity endometrium, medium-signal intensity “outer myometrium” and low-signal intensity inner myometrium (also called the “junctional zone”) on T2-weighted images 20. Abnormalities in the junctional zone are key in diagnosing adenomyosis by MRI and two- or three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasonography 21. Although there is no histologic distinction on light microscopy between the “inner myometrium” and “outer myometrium”, their embryologic origins, structure, and physiological roles differ markedly 18. During development, the inner myometrium arises from the Mullerian ducts, as does the endometrium, whereas the outer myometrium is mesenchymal in origin. The outer myometrium is absent in egg-laying animals and evolutionarily developed in uteri of viviparous animals, underscoring its role in protecting the fetus throughout gestation and mechanically facilitating expulsion of the conceptus at parturition 18. Lesser appreciated are the potential functions of the inner myometrium, which has remained mostly enigmatic in uterine biology. Myocyte (smooth muscle cell) density and arrangements differ in inner myometrium and outer myometrium, with inner myometrium exhibiting irregular, predominantly densely packed, circular muscle fibers and more vascularity compared with outer myometrium, which exhibits regular and predominantly longitudinal smooth muscle cell bundles 22. Ultrastructurally, while inner myometrium exhibits increased nuclear:cytoplasm ratio, decreased extracellular matrix (mainly elastin) with lower connective tissue-to-myocyte ratio, and lower water content compared with outer myometrium, changes from inner myometrium to outer myometrium are gradual without distinct zonation 22. At the cellular level, inner myometrium is reportedly composed of undifferentiated smooth muscle cell phenotypes compared with terminally differentiated smooth muscle cells in outer myometrium 23.

The inner myometrium, which contains fewer contractile elements than the outer myometrium, displays cycle-dependent directional (cervix←→fundus) contractions of significantly lower amplitude than in outer myometrium 24. The orientation, amplitude, and frequency of inner myometrium contractions vary throughout the menstrual cycle. During the follicular phase, retrograde contractions (cervix→fundus) can facilitate sperm transport and promote pregnancy 25. During menses, antegrade-propagated inner myometrium contractions (fundus→cervix), as well as increased amplitude of peristalsis, promote desquamation of shed endometrium 26. The contractile frequency and amplitude of the inner myometrium decreases markedly in the midluteal phase, teleologically not to interfere with embryo nidation 24. The inner myometrium is well endowed with estrogen receptors (ERs) and progesterone receptors (PRs) and increases in thickness from the early proliferative to late secretory phases 27. Thus, the circular inner myometrium plays an important role in female reproduction under the regulation of steroid hormones. In contrast, although estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor are present in outer myometrium, cyclic changes in sex steroid receptor expression is not as robust as in inner myometrium. outer myometrium is the major contractile tissue during expulsion of the fetus 28 under regulation of oxytocin and steroid hormones 29.

[Source 2 ]Figure 3. Endometrium of the uterus and its blood supply

Figure 4. Adenomyosis

Figure 5. Adenomyosis ultrasound

Footnote: Asymmetrical uterine wall thickening anteriorly with focal heterogeneity and associated increased blood flow, as well as the “venetian blind” pattern of acoustic shadowing.

[Source 8 ]If you have prolonged, heavy bleeding or severe cramping during your periods that interferes with your regular activities, make an appointment to see your doctor.

Other uterine diseases can cause signs and symptoms similar to adenomyosis, making adenomyosis difficult to diagnose. Conditions include fibroid tumors (leiomyomas), uterine cells growing outside the uterus (endometriosis) and growths in the uterine lining (endometrial polyps).

Your doctor might conclude that you have adenomyosis only after ruling out other possible causes for your signs and symptoms.

What happens when you get a period?

The endometrial tissue in the muscle undergo the same changes as the endometrial cells of the uterus. This means when you have your period, these endometrial tissue also bleed but because they are trapped in the muscle layer they form little pockets of blood within the muscle.

Who might get adenomyosis?

Adenomyosis has been found in adolescents, but typically occurs in females between the ages of 35 and 50 who have:

- At least one pregnancy.

- Endometriosis.

- Uterine fibroids.

How does adenomyosis affect pregnancy?

Adenomyosis tends to affect women who have had at least one child. However, the condition may make it difficult to conceive for the first time or to have another child. Infertility treatments may help. Once pregnant, there is an increased risk of:

- Miscarriage (loss of pregnancy before a baby fully develops).

- Premature labor (childbirth before the 37th week of pregnancy).

Adenomyosis vs Endometriosis

Adenomyosis and endometriosis are disorders that involve endometrial tissue. Both conditions can be painful. Adenomyosis is more likely to cause heavy menstrual bleeding. The difference between these conditions is where the endometrial tissue grows.

- Adenomyosis: Endometrial tissue grows into the muscle of the uterus.

- Endometriosis: Endometrial tissue grows outside the uterus and may involve the ovaries, fallopian tubes, pelvic side walls, or bowel.

Endometriosis occurs when cells similar to those that line the uterus (endometrial tissue) are found in other parts of the body such as the fallopian tubes, the ovaries or the tissue lining the pelvis (the peritoneum). In rare cases, endometriosis may grow outside the pelvic cavity, such as on the lungs or in other parts of the body 30.

About 30% of women with endometriosis have trouble with fertility and struggle to get pregnant. This is likely to affect women in different ways and can create a rollercoaster of emotions. It is thought that the reasons are related to:

- scarring of the tubes and ovaries from endometriosis

- problems with the quality of the egg

- problems with the embryo traveling down the tube and implanting in the wall of the uterus due to damage from endometriosis

- change of the organs in the pelvis such as adhesions with scarred pelvic tissue and blockage of the fallopian tubes

Once pregnant, many women also worry about the effect of their endometriosis on their pregnancy and delivery. Pregnancy does not cure endometriosis, but symptoms appear to improve during pregnancy. This is because higher progesterone levels can suppress the endometriosis. However, the effects of endometriosis after delivery of the baby are unclear. These effects may only be temporary and many women have a recurrence within a few years.

It is important to remember not all women with endometriosis are infertile. Many women have children without difficulty, have children before they are diagnosed, or eventually have a successful pregnancy.

Laparoscopic surgery (keyhole surgery using a thin telescope with a light inserted through a small cut in the belly button to look into the pelvis) is an operation to reduce symptoms and improve fertility by removing endometriotic patches, implants, cysts, nodules and adhesions by cutting them out (excision) or burning them (diathermy).

If treatment is unsuccessful, in vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatments may also be considered. However, before trying this form of treatment, it is important that your endometriosis is properly treated. IVF treatment includes increasing oestrogen levels, which will encourage the development of existing endometriosis.

Fertility treatments

Starting on fertility treatment can lead to a range of different feelings from happiness and excitement to frustration, disappointment and sadness.

If you decide to try fertility treatment, it is important both you and your partner are supported through the process. Most IVF units will have counselors who will support and counsel you through the assessment and treatment time. Getting counseling before starting treatment can help you to:

- prepare for the emotional journey ahead

- cope with any unsuccessful treatments or miscarriages

- develop strategies for coping with other people’s pregnancies/births

- talk through how both you and your partner are feeling throughout the process

Endometriosis, pregnancy and delivery

Recent studies have shown if you have endometriosis, medical care should not stop once you become pregnant. Endometriosis is a risk factor for:

- the baby being born early – before 40 weeks

- bleeding after the 24th week of pregnancy

- high blood pressure (pre-eclampsia)

- delivery by caesarean section

Endometriosis and the risk of premature birth

If you have ovarian cysts (endometriomas) and become pregnant using assisted reproductive technologies (ART), there is a greater risk of the baby:

- being born early – before 40 weeks (preterm birth)

A large study of more than 13,000 births, showed that women who were diagnosed with endometriosis had a higher risk of complications at birth, preterm birth and of having a caesarean section 31. This research information helps obstetricians identify and monitor pregnant women who have been diagnosed with endometriosis at increased risk of premature labor and birth.

Who is at risk of adenomyosis?

The known risk factors for developing adenomyosis are 32:

- conditions leading to increased estrogen exposure (increased parity, early menarche, short menstrual cycles, elevated body mass index, oral contraceptive pill use, tamoxifen use)

- previous surgery of the uterus such as a caesarean section, dilation and curettage, fibroid removal or myomectomy

- childbirth

Because of the link with childbirth or uterine surgery, adenomyosis is more likely to occur in women between 30-50 years.

Does adenomyosis affect fertility?

There is some evidence adenomyosis can reduce fertility, but this is still controversial. Due to a multitude of confounders and variable diagnostic criteria for adenomyosis, no clear association has been established 3. Studies suggest there may be changes in the ability of the uterine muscles to contract appropriately. Also, these endometrial cells inside the muscle may release body chemicals which lead to subfertility.

Mechanisms proposed for fertility impairment on the presence of adenomyosis 33:

- (i) Aberrant uterine contractility, originating from the junctional zone, which is broadened in case of adenomyosis, may impair rapid and sustained directed sperm transport

- (ii) Abnormal myometrial activity during the peri-implantation period may hinder apposition, adhesion, and penetration of the embryonic pole of the blastocyst into the decidualized endometrium

- (iii) Increased endometrial stroma vascularization in the secretory phase may derange the endometrial milieu, thus negatively affecting implantation

- (iv) Alteration in the expression profile of cytokines and growth factors in the endometrium, such as increased expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) and interleukins (IL-6, IL-8, IL-10) as well as IL-8 receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2, matrix metalloproteinases (MMP2 and MMP9) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and decreased expression of leukemia inhibiting factor (LIF), LIF receptor α, and IL-11 may be linked to adenomyosis-associated infertility

- (v) Decreased expression of HOXA-10 gene during the midluteal phase, which is considered a necessary component of endometrial receptivity and peaks during the implantation window, may negatively affect implantation

- (vi) Hyperestrogenic endometrial environment due to the increased expression of cytochrome P450 along with increased aromatase activity in the endometrium sustains the increased expression of the estrogen receptor α during the secretory phase. This in turn adversely affects cell-adhesion molecule expression, such as β3 integrins, which are deemed as key elements for the development of a receptive endometrium.

Besides the rationale for the existence of a link between adenomyosis and infertility, to date a causal relationship between these conditions has not been fully confirmed 34. On the other hand, reports of the incidence of adenomyosis in the infertile women entering an IVF/ICSI (intracytoplasmic sperm injection) program are inconsistent, varying from 6.9% to 34.3% 35. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of adenomyosis on IVF outcome reinforced the aspect of a negative impact of this condition on reproductive outcome 35. Clinical pregnancy rates in women with adenomyosis were 28% lower as compared to controls. It is noteworthy that no significant difference was seen when analysis was restricted to women undergoing a single IVF/ICSI (intracytoplasmic sperm injection) cycle. Interestingly, coexistence of endometriosis did not alter these results. Similarly, implantation rates were 23% lower in the adenomyosis group and live birth rates were 30% lower. The miscarriage rate per clinical pregnancy was also significantly increased in women with adenomyosis. The authors concluded that screening for adenomyosis in infertile women entering an IVF program is worthy and thus should be encouraged 35.

For a patient, who has a desire to preserve her reproductive function, various uterine-sparing surgical techniques have been proposed. For patients with focal adenomyosis disease and for selected cases of more diffuse adenomyosis, excision of the adenomyoma or cystectomy for cystic focal adenomyosis has been proposed 34. Partial removal of the abnormal tissue or cytoreductive surgery is reserved for cases of diffuse adenomyosis with special attention to preserve a functional uterus 34. Nonexcisional invasive treatments include laparoscopic (electrocoagulation, uterine artery ligation), hysteroscopic (ablation, transcervical resection), and other treatments, the latter including uterine artery embolization 33 and ablation with MRI-guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRIgFUS), thermoballoon, radiofrequency, or microwave 34.

Conservative medical approaches have also been applied to relieve symptoms and in women wishing to get pregnant. GnRH-analogues, aromatase inhibitors, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraception device, a danazol intrauterine contraception device, and the continuous use of estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives are all included in available treatment options 36.

Adenomyosis and pregnancy

Data concerning the association between adenomyosis and pregnancy outcome are scanty. An early study reported a prevalence of adenomyosis of 17.2% in women undergoing cesarean hysterectomy. The authors thought that the presence of adenomyosis could have impair gravid uterus functionality, thereby increasing pregnancy complications, such as postpartum hemorrhage, uterine atony, and uterine rupture 37.

A subsequent and more recent study found an increased risk for preterm birth, more frequent occurrences of fetal growth restriction and fetal malpresentation 38 and preterm premature rupture of membranes in association with adenomyosis 39. Among the pathogenic processes having been proposed so far, the authors pointed at decidual chorioamniotic or systemic inflammation, as the possible underlying mechanism for adenomyosis-related preterm delivery.

A review of the literature regarding pregnancy complications in association to adenomyosis revealed only 29 cases. In particular, uterine rupture, postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony, and ectopic pregnancy were reported in relation to adenomyosis in the gravid uterus 40.

Adenomyosis causes

It is not certain how or why the uterus-lining cells enter the muscle wall. However there are a number of theories for the causes of adenomyosis:

- Invasive tissue growth. Some experts believe that adenomyosis results from the direct invasion of endometrial cells from the lining of the uterus into the muscle that forms the uterine walls. Uterine incisions made during an operation such as a cesarean section (C-section) might promote the direct invasion of the endometrial cells into the wall of the uterus.

- Developmental origins. Other experts suspect that adenomyosis originates within the uterine muscle from endometrial tissue deposited there when the uterus first formed in the fetus.

- Uterine inflammation related to childbirth. Another theory suggests a link between adenomyosis and childbirth. Inflammation of the uterine lining during the postpartum period might cause a break in the normal boundary of cells that line the uterus. Surgical procedures on the uterus can have a similar effect.

- Stem cell origins. A recent theory proposes that bone marrow stem cells might invade the uterine muscle, causing adenomyosis.

The most commonly accepted theory is that adenomyosis results from a disrupted boundary between the deepest layer of the endometrium (endometrium basalis) and the underlying myometrium 4. This process leads to a cycle of inappropriate endometrial proliferation into the myometrium with subsequent small vessel angiogenesis as well as adjacent myometrial smooth muscle hypertrophy and hyperplasia. Data demonstrating a higher prevalence of adenomyosis following dilation and curettage and cesarean section support this theory 41.

A second theory proposes an embryologic mechanism whereby pluripotent Mullerian stem cells undergo inappropriate differentiation leading to ectopic endometrial tissue. This theory has support from evidence demonstrating altered expression of specific genetic markers, in addition to case reports of endometrial tissue found in women with Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome (Mullerian agenesis) 42.

Other less well-accepted theories propose altered lymphatic drainage pathways and displaced bone marrow stem cells to explain the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue 32.

Adenomyosis sometimes happens after:

- the birth of a baby

- surgery involving the uterus, such as caesarean section or removal of uterine fibroids.

Regardless of how adenomyosis develops, its growth depends on the circulating estrogen in women’s bodies.

Risk factors for adenomyosis

Risk factors for adenomyosis include:

- Prior uterine surgery, such as a caesarean section (C-section) or fibroid removal

- Childbirth

- Middle age

Most cases of adenomyosis — which depends on estrogen — are found in women in their 40s and 50s. Adenomyosis in these women could relate to longer exposure to estrogen compared with that of younger women. However, current research suggests that the condition might be common in younger women.

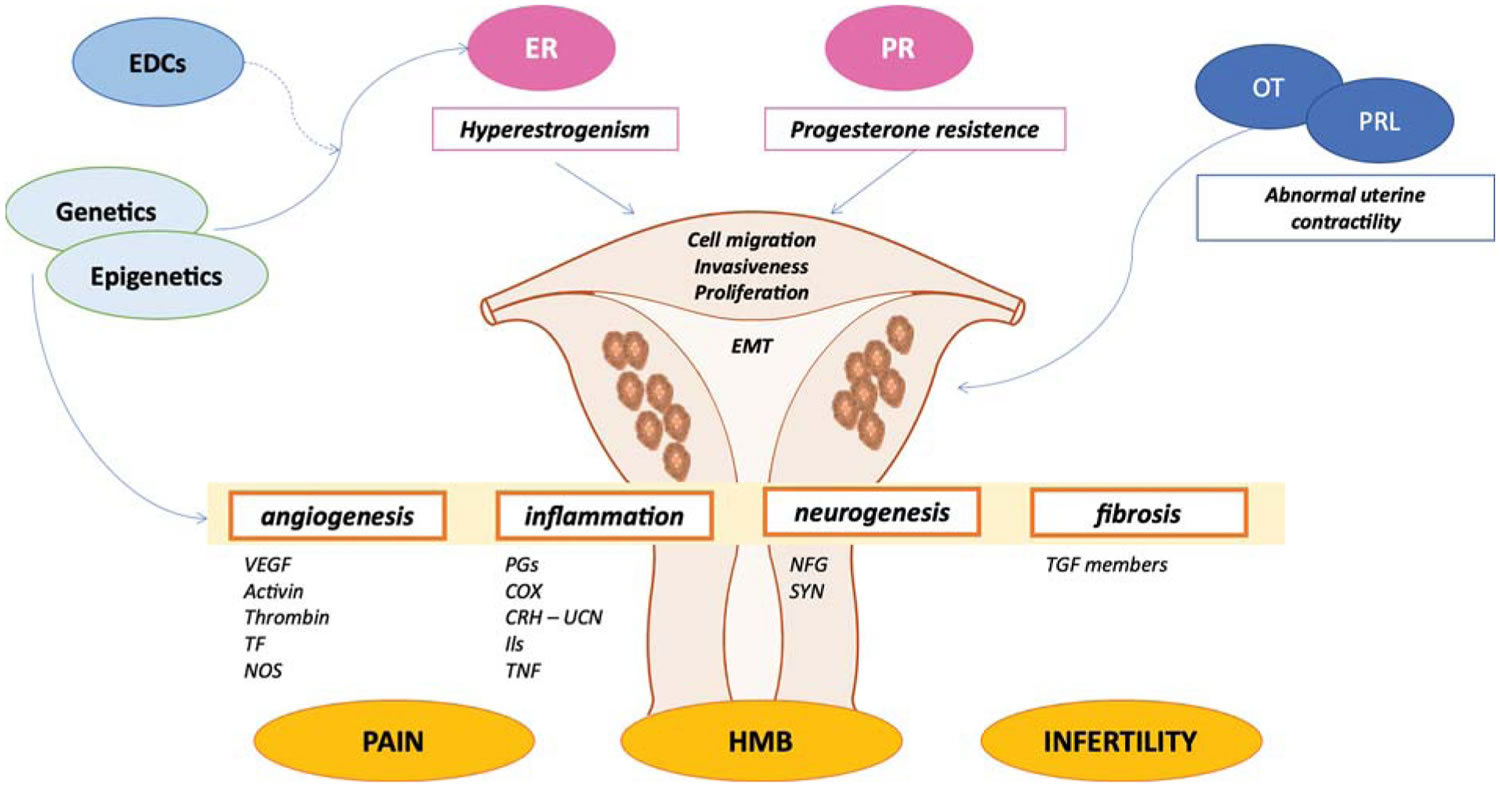

Adenomyosis pathophysiology

Disruption in the endometrial-myometrial junction is now considered an important contributor to reproductive problems such as recurrent implantation failure, a condition that can prevent women falling pregnant.

Inappropriate endometrial tissue proliferation within the myometrium leads to symptoms through a variety of mechanisms. Normal endometrial tissue is responsible for prostaglandin production which drives the contractions of menstruation. Ectopic foci of adenomyosis lead to increased levels of prostaglandins which result in dysmenorrhea which characterizes the disease. Estrogen also drives endometrial proliferation, which medical therapies aim to reduce.

Heavy menstrual bleeding is thought to be caused by a combination of factors which include increased endometrial surface area, increased vascularization, abnormal uterine contractions, and increased cell signaling molecules such as prostaglandins, eicosanoids, and estrogen 32.

Figure 6. Adenomyosis pathophysiology

Footnotes: Abnormal genetic and epigenetic factors result in the hyperestrogenism and progesterone resistance, promoting cell proliferation, migration, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and invasiveness of endometrial cellular components into the myometrial compartment. Moreover, genetics and epigenetics modifications also contribute to the development of pelvic pain, infertility, and heavy menstrual bleeding experienced by women with adenomyosis through different mediators. In addition, pituitary hormones such as prolactin and oxytocin also play a role in the pathogenesis of adenomyosis through abnormal uterine contractility.

Abbreviations: EDCs = endocrine disrupting chemicals; EMT = epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; ER = estrogen receptor; HMB = heavy menstrual bleeding; OT = oxytocin; PR = progesterone receptor; PRL = prolactin.

[Source 2 ]Adenomyosis symptoms

Most patients with adenomyosis are asymptomatic 43. Symptoms related to adenomyosis include painful periods (dysmenorrhea), heavy periods (menorrhagia), pain during sex (dyspareunia), chronic pelvic pain, and prolonged or excessive uterine bleeding that occurs irregularly (menometrorrhagia) 44. Pelvic tenderness on examination is associated with diffuse enlargement of the uterus.

Often, symptoms start late in the childbearing years after women have children. Women with adenomyosis might have:

- heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia)

- painful periods (dysmenorrhea)

- pain during sex (dyspareunia)

- bleeding between periods

- tiredness from the anemia caused by blood loss

- infertility

- pelvic pain

- enlarged uterus

These symptoms might be mild, but they can be severe enough to interfere with work and your enjoyment of life.

Your uterus might get bigger. Although you might not know if your uterus is enlarged, you may notice that your lower abdomen feels tender or causes pelvic pressure.

Adenomyosis complications

If you often have prolonged, heavy bleeding during your periods, you can develop chronic anemia. Anemia occurs when your body doesn’t have enough iron-rich red blood cells, which causes fatigue and other health problems.

Although not harmful, the pain and excessive bleeding associated with adenomyosis can disrupt your lifestyle. You might avoid activities you’ve enjoyed in the past because you’re in pain or you worry you might start bleeding.

Adenomyosis diagnosis

Your doctor may suspect adenomyosis based on:

- Signs and symptoms

- A pelvic exam that reveals an enlarged, tender uterus

- Ultrasound imaging of the uterus

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the uterus

In some instances, your doctor might collect a sample of uterine tissue for testing (endometrial biopsy) to verify that your abnormal uterine bleeding isn’t associated with another serious condition. But an endometrial biopsy won’t help your doctor confirm a diagnosis of adenomyosis.

The only way to confirm adenomyosis is to examine the uterus after hysterectomy. However, pelvic imaging such as ultrasound and MRI can detect signs of it.

Other uterine diseases can cause signs and symptoms similar to adenomyosis, making adenomyosis difficult to diagnose. Conditions include fibroid tumors (leiomyomas), uterine cells growing outside the uterus (endometriosis) and growths in the uterine lining (endometrial polyps).

Your doctor might conclude that you have adenomyosis only after ruling out other possible causes for your signs and symptoms.

Adenomyosis treatment

Because the female hormone estrogen promotes endometrial tissue growth (estrogen thickens the uterine wall and can worsen bleeding and cramping), adenomyosis often goes away after menopause, so treatment might depend on how close you are to that stage of life.

Treatment of adenomyosis varies widely from simple medication to a total hysterectomy and several options in between. To date, the choice of therapy for adenomyosis is still individualized and should rely on the clinical presentation of patients and the desire for future pregnancy, especially with the increasing number of nulliparous, younger patients with this condition 45. Levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD) is effective, non-invasive, and fertility-preserving and seems to be the superior choice of treatment for this population.

Surgical treatment is most effective when the adenomyosis is localized to a smaller area and can be removed, and this type of surgery doesn’t prevent women falling pregnant in the future. If the adenomyosis is spread throughout a larger area then treatments include destroying the lining of the uterus (endometrial ablation) provided adenomyosis is not too deep, and hysterectomy (surgery to remove a woman’s uterus), both of which will prevent further pregnancy. Removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) cures adenomyosis.

Other treatment options are interventional radiology such as uterine artery embolization, where the blood supply to the uterus is cut off and magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound where the adenomyosis is destroyed with ultrasound energy.

Treatment options for adenomyosis include:

- Anti-inflammatory drugs also known as Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs). Your doctor might recommend anti-inflammatory medications, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or naproxen (Aleve), to control your pain. By starting an anti-inflammatory medicine one to two days before your period begins and taking it during your period, you can reduce menstrual blood flow and help relieve pain. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) have been proven to control the pain by decreasing the production of prostaglandins 46. These medications provide only symptomatic treatment and have no effect on the adenomyotic process.

- Hormone medications. Combined estrogen-progestin birth control pills or hormone-containing patches or vaginal rings might lessen heavy bleeding and pain associated with adenomyosis 47. Progestin-only contraception, such as an intrauterine device (IUD) or continuous-use birth control pills often lead to amenorrhea — the absence of your menstrual periods — which might provide some relief. Suppressive hormonal therapies have been used to temporarily induce regression of adenomyosis and improve symptoms 48. In a case series, Mansouri et al. 49 showed regression of adenomyosis on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) after treatment with a course of oral contraceptive pills in one patient and resolution of adenomyosis on imaging and of chronic pelvic pain clinically after treatment with leuprolide acetate, a GnRH agonist, in 3 other patients. In a systematic review of randomized controlled trials by Brown et al. 50, GnRH agonist therapy was found to be superior to no treatment and placebo, but there was no statistical difference between GnRH agonist and danazol for dysmenorrhea, or GnRH agonist and levonorgestrel for overall pain 51. More adverse effects were reported in the GnRH agonist group, which might be a factor in limiting its use 51.

- Progestogen releasing intrauterine device (IUD) such as Mirena. The insertion of a progestogen releasing intrauterine device (IUD) can cause:

- a thinning of the endometrium

- a reduction in the size of the uterus

- a reduction in the pain experienced with intercourse

- reduced bleeding

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (an artificial hormone used to prevent natural ovulation). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists cause:

- a thinning of the endometrium

- a reduction in the size of the uterus

- suppression of the period

- a temporary chemical menopause

- In the presence of infertility and endometriosis these may be used temporarily.

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists are a class of medications that antagonize (block) the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor (GnRH receptor) and thus the action of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). There are two case reports on the use of GnRH antagonists for treating adenomyosis. Donnez et al. 52 reported a case of a patient who was prescribed Linzagolix, a GnRH antagonist for adenomyosis after failing a course of ulipristal acetate. Linzagolix significantly reduced adenomyotic lesion size and improved the patient’s dysmenorrhea and quality of life 52. Similarly, Kavoussi et al. 53 reported a case of a 41 year old patient who presented with a fundal adenomyoma that regressed in size after treatment with Elagolix, another GnRH antagonist. The patient also reported improvement in her clinical symptoms and resolution of her pelvic pain while on this regimen 53. These observations make it worthy to further look into GnRH antagonists as a prospective treatment option for adenomyosis.

- Danazol-loaded IUD. Danazol is an androgenic hormone used in the treatment of endometriosis to shrink the ectopic endometrial tissue. Igarashi et al. 54 extended the use of this hormone in adenomyosis and tested out the use of a danazol-loaded IUD in patients with adenomyosis. In 3 different trials, the danazol IUD was inserted in adenomyotic uteri and was found to improve dysmenorrhea and decrease myometrial thickness, with significantly less side effects given the lower serum concentrations compared to oral danazol 55. Shawki and Igarashi also showed a possible positive effect on improved fertility after removal of danazol IUD 56.

- Progestogen releasing intrauterine device (IUD) such as Mirena. The insertion of a progestogen releasing intrauterine device (IUD) can cause:

- Endometrial ablation may be considered in patients who do not desire future fertility but prefer a less invasive alternative to hysterectomy. Limitations include the inability to target deeper adenomyotic foci due to its superficial approach.

- Myomectomy and partial hysterectomy are more invasive options that aim to preserve fertility. These options allow for targeting of deeper foci; however, subsequent scarring may lead to disease recurrence as the endometrial-myometrial interface is disrupted, a risk factor for adenomyosis. Additional considerations include the potential for future pregnancy complications due to altered uterine anatomy with an increased risk of uterine rupture, premature rupture of membranes, premature labor, and spontaneous abortion 3.

- Uterine artery embolization reduces blood flow to the uterus as a whole, thereby inducing necrosis leading to an overall reduction in uterine size 57. These therapies show promise but require additional data on direct treatment comparisons and long-term outcomes 3. While these therapies aim to preserve fertility, infertility is an understood risk.

- Hysterectomy. If your pain is severe and no other treatments have worked, your doctor might suggest surgery to remove your uterus. Removing your ovaries isn’t necessary to control adenomyosis. After a hysterectomy, you won’t have a menstrual cycle or be able to get pregnant.

You can ease adenomyosis pain and cramps by:

- Taking an over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medication, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others).

- Using warm baths and heat packs. Use a heating pad on your abdomen.

- Hormone treatment

- Insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD) that releases the hormone progesterone

Hysterectomy is an option for women with severe adenomyosis.

Treatment for an adenomyoma (mass of adenomyosis in one area):

- Laparoscopy (keyhole surgery): An adenoyoma may be surgically removed using keyhole surgery.

- High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU): Guided by an MRI, high intensity focused ultrasound waves cause a localised increase in temperature to the adenomyoma causing the cells to die 58. High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) showed a significant decrease in dysmenorrhea scores and in volume of adenomyotic lesions across several studies 59. Menorrhagia also seems to significantly improve after treatment with HIFU in both focal and diffuse adenomyosis 60. Results were sustained at 2 years follow up as shown by Shui et al. such that the dysmenorrhea relief rate was 82.3% and menorrhagia relief rate reached 78.9% at 2 years post treatment 61. When compared to laparoscopic excision, HIFU showed significantly higher pregnancy and natural conception rates and was comparable to excision in terms of pain and menorrhagia reduction 62. Further studies are required to determine fertility outcomes.

- Radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is a medical procedure that uses a high-frequency alternating current produced by a radiofrequency generator oscillating in a closed-loop circuit. This current heats a needle to over 60 °C, which is used to cause intentional protein denaturation and tissue damage 63. Radiofrequency ablation of adenomyotic lesions is another promising uterine-preserving option for focal adenomyosis. Scarperi et al. 64 found a significant reduction in adenomyosis volume (24.2 vs. 60 cm³) and a 68.1% visual analog scale score reduction at 9 months post laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation. Hai et al. 65 performed ultrasound-guided transcervical radiofrequency ablation for adenomyosis on 87 patients and reported a 41.2% uterine volume reduction and a focal adenomyosis volume decrease of 54.7% at 12 months post treatment. The visual analog scale scores significantly declined from 6.9 to 1.9 at 12 months follow up and symptoms severity score also showed a drop from 44 to 11.85 at 12 months 65. Radiofrequency ablation was also shown to maintain fertility with a pregnancy success rate reaching up to 50% making it a desirable option for patients who wish to conceive 66. Radiofrequency ablation is also effective when combined with levonorgestrel-releasing-IUD demonstrated by a reduction of uterine volume and a decrease in dysmenorrhea 67.

Lifestyle modifications

Some women have found that their pain is improved by exercise and relaxation techniques. Although natural supplements have not been shown to reduce endometriosis-related pain, over-the-counter, nonsteroidal, anti-inflammatory medications, like ibuprofen and naproxen, reduce painful menstrual cramps. When painful intercourse is a problem, changing positions prevents pain caused by deep penetration. In spite of these measures, medical treatment is frequently needed.

Adenomyosis prognosis

Adenomyosis is a difficult diagnosis to manage as multiple clinical factors must be considered, including fertility, confidence in diagnosis, side effects of medical management, and risk of invasive procedures. Recent data showing an increased prevalence of adenomyosis in younger populations and asymptomatic patients reflects a spectrum of disease which is incompletely understood. Symptoms seem to correlate with the number of adenomyosis foci and the depth of invasion 68. Many women who experience life-disrupting symptoms from adenomyosis find relief through hormonal treatments and pain relievers, with progression to minimally invasive procedures such as endometrial ablation/myomectomy or uterine artery embolization. A hysterectomy is a permanent solution that provides long-term symptom relief. After menopause, symptoms should go away.

References- History of adenomyosis. Benagiano G, Brosens I. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2006 Aug; 20(4):449-63. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16515887/

- Zhai, J., Vannuccini, S., Petraglia, F., & Giudice, L. C. (2020). Adenomyosis: Mechanisms and Pathogenesis. Seminars in reproductive medicine, 38(2-03), 129–143. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1716687

- Abbott JA. Adenomyosis and Abnormal Uterine Bleeding (AUB-A)-Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017 Apr;40:68-81. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2016.09.006

- Gunther R, Walker C. Adenomyosis. [Updated 2021 Jul 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539868

- Kriplani A, Mahey R, Agarwal N, Bhatla N, Yadav R, Singh MK. Laparoscopic management of juvenile cystic adenomyoma: four cases. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 May-Jun;18(3):343-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2011.02.001

- Adenomyosis. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/adenomyosis

- Tamai K, Togashi K, Ito T et-al. MR imaging findings of adenomyosis: correlation with histopathologic features and diagnostic pitfalls. Radiographics. 25 (1): 21-40. doi:10.1148/rg.251045060

- Adenomyosis. https://radiopaedia.org/cases/adenomyosis-4

- Diffuse uterine adenomyosis. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/diffuse-uterine-adenomyosis

- Imaoka I, Ascher SM, Sugimura K, Takahashi K, Li H, Cuomo F, Simon J, Arnold LL. MR imaging of diffuse adenomyosis changes after GnRH analog therapy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002 Mar;15(3):285-90. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10060

- Byun JY, Kim SE, Choi BG, Ko GY, Jung SE, Choi KH. Diffuse and focal adenomyosis: MR imaging findings. Radiographics. 1999 Oct;19 Spec No:S161-70. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.suppl_1.g99oc03s161

- Cystic adenomyosis. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/cystic-adenomyosis

- Adenomyotic cyst. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/adenomyotic-cyst

- New interventional techniques for adenomyosis. Rabinovici J, Stewart EA. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2006 Aug; 20(4):617-36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16934530/

- Deep pelvic endometriosis: MR imaging for diagnosis and prediction of extension of disease. Bazot M, Darai E, Hourani R, Thomassin I, Cortez A, Uzan S, Buy JN. Radiology. 2004 Aug; 232(2):379-89. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15205479/

- Adenomyosis in endometriosis–prevalence and impact on fertility. Evidence from magnetic resonance imaging. Kunz G, Beil D, Huppert P, Noe M, Kissler S, Leyendecker G. Hum Reprod. 2005 Aug; 20(8):2309-16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15919780/

- Agostinho L, Cruz R, Osório F, Alves J, Setúbal A, Guerra A. MRI for adenomyosis: a pictorial review. Insights Imaging. 2017;8(6):549-556. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5707223

- Naftalin J, Jurkovic D. The endometrial-myometrial junction: a fresh look at a busy crossing. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Jul;34(1):1-11. doi: 10.1002/uog.6432

- Hricak H, Alpers C, Crooks LE, Sheldon PE. Magnetic resonance imaging of the female pelvis: initial experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983 Dec;141(6):1119-28. doi: 10.2214/ajr.141.6.1119

- Brosens JJ, de Souza NM, Barker FG. Uterine junctional zone: function and disease. Lancet. 1995 Aug 26;346(8974):558-60. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91387-4

- Rasmussen CK, Hansen ES, Dueholm M. Two- and three-dimensional ultrasonographic features related to histopathology of the uterine endometrial-myometrial junctional zone. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019 Feb;98(2):205-214. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13484

- Mehasseb MK, Bell SC, Brown L, Pringle JH, Habiba M. Phenotypic characterisation of the inner and outer myometrium in normal and adenomyotic uteri. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011;71(4):217-24. doi: 10.1159/000318205

- Kishi Y, Shimada K, Fujii T, Uchiyama T, Yoshimoto C, Konishi N, Ohbayashi C, Kobayashi H. Phenotypic characterization of adenomyosis occurring at the inner and outer myometrium. PLoS One. 2017 Dec 18;12(12):e0189522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189522

- Ijland MM, Evers JL, Dunselman GA, van Katwijk C, Lo CR, Hoogland HJ. Endometrial wavelike movements during the menstrual cycle. Fertil Steril. 1996 Apr;65(4):746-9. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58207-7

- Kunz G, Beil D, Deininger H, Wildt L, Leyendecker G. The dynamics of rapid sperm transport through the female genital tract: evidence from vaginal sonography of uterine peristalsis and hysterosalpingoscintigraphy. Hum Reprod. 1996 Mar;11(3):627-32. doi: 10.1093/humrep/11.3.627

- Lyons EA, Taylor PJ, Zheng XH, Ballard G, Levi CS, Kredentser JV. Characterization of subendometrial myometrial contractions throughout the menstrual cycle in normal fertile women. Fertil Steril. 1991 Apr;55(4):771-4. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54246-0

- Hoad CL, Raine-Fenning NJ, Fulford J, Campbell BK, Johnson IR, Gowland PA. Uterine tissue development in healthy women during the normal menstrual cycle and investigations with magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Feb;192(2):648-54. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.07.032

- Aguilar HN, Mitchell BF. Physiological pathways and molecular mechanisms regulating uterine contractility. Hum Reprod Update. 2010 Nov-Dec;16(6):725-44. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq016

- Kurowicka B, Franczak A, Oponowicz A, Kotwica G. In vitro contractile activity of porcine myometrium during luteolysis and early pregnancy: effect of oxytocin and progesterone. Reprod Biol. 2005 Jul;5(2):151-69.

- Office on Women’s Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2009). Endometriosis fact sheet. http://www.womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/fact-sheet/endometriosis.html

- Stephansson O, Kieler H, Granath F, Falconer H. Endometriosis assisted reproduction technology, and risk of adverse pregnancy outcome. Human Reproduction. 2009;24(9): 2341-7.

- Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: A Clinical Review of a Challenging Gynecologic Condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016 Feb 1;23(2):164-85. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2015.09.018

- Vlahos NF, Theodoridis TD, Partsinevelos GA. Myomas and Adenomyosis: Impact on Reproductive Outcome. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:5926470. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5694987/

- Uterus-sparing operative treatment for adenomyosis. Grimbizis GF, Mikos T, Tarlatzis B. Fertil Steril. 2014 Feb; 101(2):472-87. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24289992/

- Uterine adenomyosis and in vitro fertilization outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vercellini P, Consonni D, Dridi D, Bracco B, Frattaruolo MP, Somigliana E. Hum Reprod. 2014 May; 29(5):964-77. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24622619/

- Habiba M., Benagiano G. Uterine Adenomyosis. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

- Adenomyosis in the gravid uterus at term. SANDBERG EC, COHN F. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1962 Dec 1; 84():1457-65. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13976185/

- Adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with adenomyosis with uterine enlargement. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015 Apr;41(4):529-33. doi: 10.1111/jog.12604. Epub 2014 Nov 3. https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/jog.12604

- Adenomyosis and risk of preterm delivery. Juang CM, Chou P, Yen MS, Twu NF, Horng HC, Hsu WL. BJOG. 2007 Feb; 114(2):165-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17169011/

- Adenomyosis in pregnancy. A review. Azziz R. J Reprod Med. 1986 Apr; 31(4):224-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3712359/

- Taran, F. A., Stewart, E. A., & Brucker, S. (2013). Adenomyosis: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Clinical Phenotype and Surgical and Interventional Alternatives to Hysterectomy. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde, 73(9), 924–931. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1350840

- Garcia L, Isaacson K. Adenomyosis: review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Jul-Aug;18(4):428-37. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2011.04.004

- Adenomyosis https://radiopaedia.org/articles/adenomyosis

- Sakhel K, Abuhamad A. Sonography of adenomyosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31 (5): 805-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22535729

- Sharara, F. I., Kheil, M. H., Feki, A., Rahman, S., Klebanoff, J. S., Ayoubi, J. M., & Moawad, G. N. (2021). Current and Prospective Treatment of Adenomyosis. Journal of clinical medicine, 10(15), 3410. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10153410

- Marjoribanks J, Ayeleke RO, Farquhar C, Proctor M. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jul 30;2015(7):CD001751. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001751.pub3

- Wong CL, Farquhar C, Roberts H, Proctor M. Oral contraceptive pill for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Oct 7;2009(4):CD002120. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002120.pub3

- Pontis A, D’Alterio MN, Pirarba S, de Angelis C, Tinelli R, Angioni S. Adenomyosis: a systematic review of medical treatment. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016 Sep;32(9):696-700. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2016.1197200

- Mansouri R, Santos XM, Bercaw-Pratt JL, Dietrich JE. Regression of Adenomyosis on Magnetic Resonance Imaging after a Course of Hormonal Suppression in Adolescents: A Case Series. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015 Dec;28(6):437-40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.12.009

- Brown J, Pan A, Hart RJ. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Dec 8;2010(12):CD008475. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008475.pub2

- Donnez O., Donnez J. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist (linzagolix): A new therapy for uterine adenomyosis. Fertil. Steril. 2020;114:640–645. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.04.017

- Kavoussi S.K., Esqueda A.S., Jukes L.M. Elagolix to medically treat a uterine adenomyoma: A case report. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020;247:266–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.02.027

- Fong YF, Singh K. Medical treatment of a grossly enlarged adenomyotic uterus with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 1999 Sep;60(3):173-5. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(99)00075-x

- Igarashi M. Further studies on danazol-loaded IUD in uterine adenomyosis. Fertil. Steril. 2002;77:S25. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)03087-4

- Shawki O., Igarashi M. Danazol loaded intrauterine device (IUD) for management of uterine adenomyosis: A novel approach. Fertil. Steril. 2002;77:S24. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)03085-0

- Liang E, Brown B, Kirsop R, Stewart P, Stuart A. Efficacy of uterine artery embolisation for treatment of symptomatic fibroids and adenomyosis – an interim report on an Australian experience. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012 Apr;52(2):106-12. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2011.01399.x

- Cheung VYT. High-intensity focused ultrasound therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018 Jan;46:74-83. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.09.002

- Li W, Mao J, Liu Y, Zhu Y, Li X, Zhang Z, Bai X, Zheng W, Wang L. Clinical effectiveness and potential long-term benefits of high-intensity focused ultrasound therapy for patients with adenomyosis. J Int Med Res. 2020 Dec;48(12):300060520976492. doi: 10.1177/0300060520976492

- Dev B, Gadddam S, Kumar M, Varadarajan S. MR-guided focused ultrasound surgery: A novel non-invasive technique in the treatment of adenomyosis -18 month’s follow-up of 12 cases. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2019 Jul-Sep;29(3):284-288. doi: 10.4103/ijri.IJRI_53_19

- Shui L, Mao S, Wu Q, Huang G, Wang J, Zhang R, Li K, He J, Zhang L. High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) for adenomyosis: Two-year follow-up results. Ultrason Sonochem. 2015 Nov;27:677-681. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.05.024

- Huang YF, Deng J, Wei XL, Sun X, Xue M, Zhu XG, Deng XL. A comparison of reproductive outcomes of patients with adenomyosis and infertility treated with High-Intensity focused ultrasound and laparoscopic excision. Int J Hyperthermia. 2020;37(1):301-307. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2020.1742390

- Pereira PL, Trübenbach J, Schenk M, Subke J, Kroeber S, Schaefer I, Remy CT, Schmidt D, Brieger J, Claussen CD. Radiofrequency ablation: in vivo comparison of four commercially available devices in pig livers. Radiology. 2004 Aug;232(2):482-90. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2322030184

- Scarperi S, Pontrelli G, Campana C, Steinkasserer M, Ercoli A, Minelli L, Bergamini V, Ceccaroni M. Laparoscopic Radiofrequency Thermal Ablation for Uterine Adenomyosis. JSLS. 2015 Sep-Dec;19(4):e2015.00071. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2015.00071

- Hai N, Hou Q, Ding X, Dong X, Jin M. Ultrasound-guided transcervical radiofrequency ablation for symptomatic uterine adenomyosis. Br J Radiol. 2017 Jan;90(1069):20160119. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20160119

- Nam JH. Pregnancy and symptomatic relief following ultrasound-guided transvaginal radiofrequency ablation in patients with adenomyosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2020 Jan;46(1):124-132. doi: 10.1111/jog.14145

- Hai N., Hou Q., Guo R. Ultrasound-guided transvaginal radiofrequency ablation combined with levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for symptomatic uterine adenomyosis treatment. Int. J. Hyperth. 2021;38:65–69. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2021.1874063

- Levgur M, Abadi MA, Tucker A. Adenomyosis: symptoms, histology, and pregnancy terminations. Obstet Gynecol. 2000 May;95(5):688-91. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00659-6