Amoebiasis

Amoebiasis also known as amebiasis or amoebic dysentery, is an intestinal infection caused by a protozoan parasite called Entamoeba histolytica and possibly other Entamoeba species that is transmitted by fecal–oral route, either by eating or drinking fecally contaminated food or water or person-to-person contact (such as by diaper changing or sexual activity) 1, 2. The majority of Entamoeba histolytica infections restricted to the lumen of the intestine (“luminal amebiasis”) are asymptomatic. Amoebiasis may present with no symptoms or mild to severe symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, or bloody diarrhea. Amoebic dysentery results in severe diarrhea containing blood or mucus with painful stomach cramps, nausea and high fever. Severe complications may include inflammation and perforation, resulting in peritonitis. People affected with intestinal amebiasis may develop anemia 3. If the Entamoeba histolytica parasite reaches the bloodstream, it can spread through the body and end up in the liver, causing amoebic liver abscesses. Liver abscesses can occur without previous diarrhea. People at higher risk for severe amoebiasis disease are those who are pregnant, immunocompromised, or receiving corticosteroids. Men are at higher risk of developing amebic liver abscess than are women for reasons not fully understood, often presenting between the ages of 20 and 40 years 4. Amoebic liver abscess caused by Entamoeba histolytica is presently the third most common cause of death from parasitic diseases 5. Most of the studies from the tropical areas illustrate the fact that amoebic liver abscess is extremely common among males who consume alcohol beverages, in particular the indigenous variety 6.

Amoebiasis (amebiasis) is distributed worldwide, particularly in the tropical areas, most commonly in areas of poor sanitation where fresh water or food is contaminated with human feces. This is sometimes due to the use of human waste as fertilizer. The majority of amebiasis cases occur in developing countries. Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia, and India have significant health problems from amebiasis. In developed countries such as the United States, amebiasis is most often seen in recent immigrants and refugees from these areas are also at risk, travelers to an endemic area, homosexuals, institutionalized or immunocompromised individuals 7. Long-term travelers (duration >6 months) are significantly more likely than short-term travelers (duration <1 month) to develop E. histolytica infection 1. Amebiasis is also spread through person-to-person contact. Amoebiasis outbreaks among men who have sex with men have been reported. Amoebiasis associations with diabetes and alcohol use have also been reported.

Entamoeba histolytica is classified as a category B biodefense organism because of its environmental stability, ease of dissemination, resistance to chlorine, and its ability to easily spread through contaminated food products.

Globally, approximately 50 million people contract amoebiasis, with over 100,000 deaths due to amebiasis reported annually 3. Despite the global public health burden, there are no vaccines or prophylactic medications to prevent amebiasis 8.

Amoebiasis diagnosis is typically by stool examination using a microscope. Detection of the pathogenic E. histolytica and its differentiation from the non-pathogenic Entamoeba species play a crucial role in the clinical management of patients. An increased white blood cell count may be present. The most accurate test is antigen detection using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to confirm the diagnosis of E. histolytica 9.

All patients with amebiasis should be treated 4. Amoebiasis treatment depends on how severe the infection is. Usually, antibiotics are prescribed. Two treatment options are possible, for symptomatic intestinal amoebiasis and extraintestinal disease, treatment with antibiotics such as metronidazole or tinidazole should be followed by treatment with luminal cysticidal agent such as iodoquinol or paromomycin. Asymptomatic patients infected with E. histolytica should only be treated with luminal cysticidal agent such as iodoquinol or paromomycin to get rid of all the amoeba in the intestine and to prevent the disease from coming back, because they can infect others and because 4%–10% develop disease within a year if left untreated.

If you are vomiting, you may be given medicines through a vein (intravenously) until you can take them by mouth. Medicines to stop diarrhea are usually not prescribed because they can make the condition worse.

After antibiotic treatment, your stool will likely be rechecked to make sure the infection has been cleared.

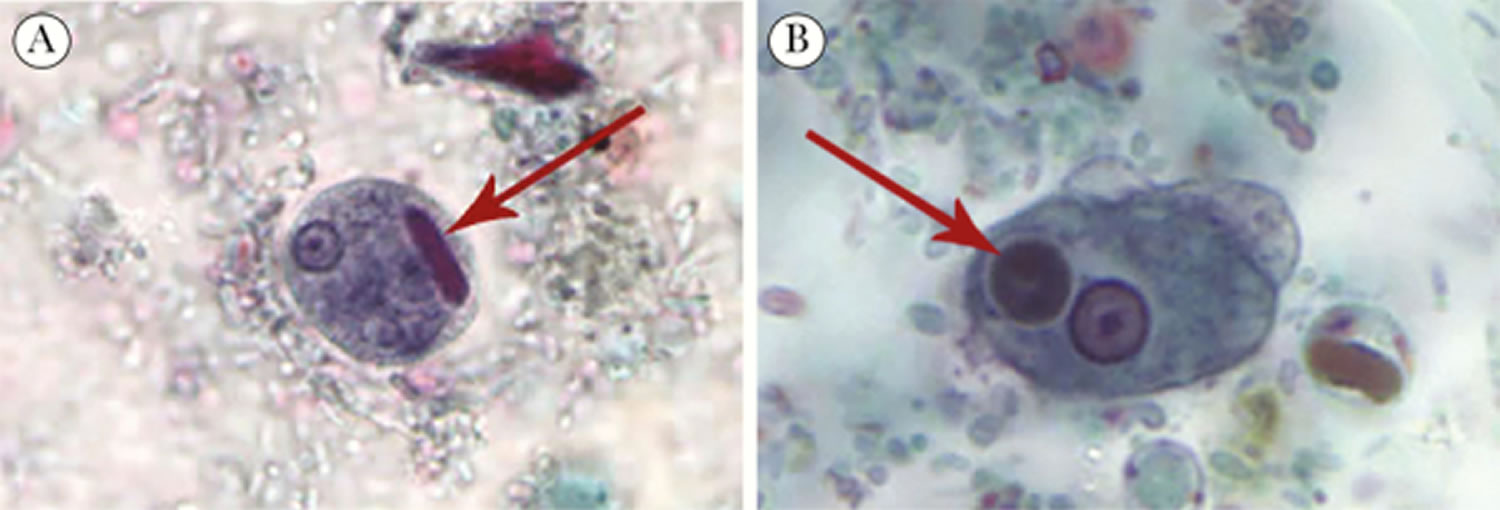

Figure 1. Entamoeba histolytica

Figure 2. Entamoeba histolytica in stool

Footnote: Entamoeba histolytica in stool and pathological features of intestinal amebiasis. (A) Cyst of E. histolytica/E. dispar stained with trichrome. Note the chromatoid body with blunt ends (red arrow). (B) Trophozoite of E. histolytica with ingested erythrocytes stained with trichrome. The ingested erythrocytes appear as dark inclusions (red arrow). The parasite shows nuclei that have the typical small, centrally located karyosome and thin, uniform peripheral chromatin.

[Source 4 ]Who is at risk for amebiasis?

Although anyone can have amoebiasis disease, it is more common in people who live in tropical areas with poor sanitary conditions. In the United States, amebiasis is most common in:

- People who have traveled to tropical places that have poor sanitary conditions

- Immigrants from tropical countries that have poor sanitary conditions

- People who live in institutions that have poor sanitary conditions

- Men who have sex with men

How can I become infected with amoebiasis?

Entamoeba histolytica infection can occur when a person:

- Puts anything into their mouth that has touched the feces (poop) of a person who is infected with E. histolytica.

- Swallows something, such as water or food, that is contaminated with E. histolytica.

- Swallows E. histolytica cysts (eggs) picked up from contaminated surfaces or fingers.

If I swallowed E. histolytica, how quickly would I become sick?

Only about 10% to 20% of people who are infected with E. histolytica become sick from the infection. Those people who do become sick usually develop symptoms within 2 to 4 weeks, though it can sometimes take longer.

How you can avoid passing on amoebiasis?

Handwashing is the most important way to stop the spread of infection. You’re infectious to other people while you’re ill and have symptoms.

Take the following steps to avoid passing amebiasis on to others:

- Wash your hands thoroughly with soap and water after going to the toilet.

- Stay away from work or school until you’ve been completely free from any symptoms for at least 48 hours.

- Help young children to wash their hands properly.

- Do not prepare food for others until you’ve been free of symptoms for at least 48 hours.

- Do not go swimming until you’ve been free of symptoms for at least 48 hours.

- Where possible, stay away from other people until your symptoms have stopped.

- Wash all dirty clothes, bedding and towels on the hottest cycle of your washing machine.

- Clean toilet seats and toilet bowls, flush handles, taps and sinks with detergent and hot water after use, followed by a household disinfectant.

- Avoid sexual contact until you’ve been free of symptoms for at least 48 hours.

Risk groups are people with certain jobs (including healthcare workers and people who handle food), as well as people who need help with personal hygiene and very young children. Your environmental health officer will be able to advise you about this.

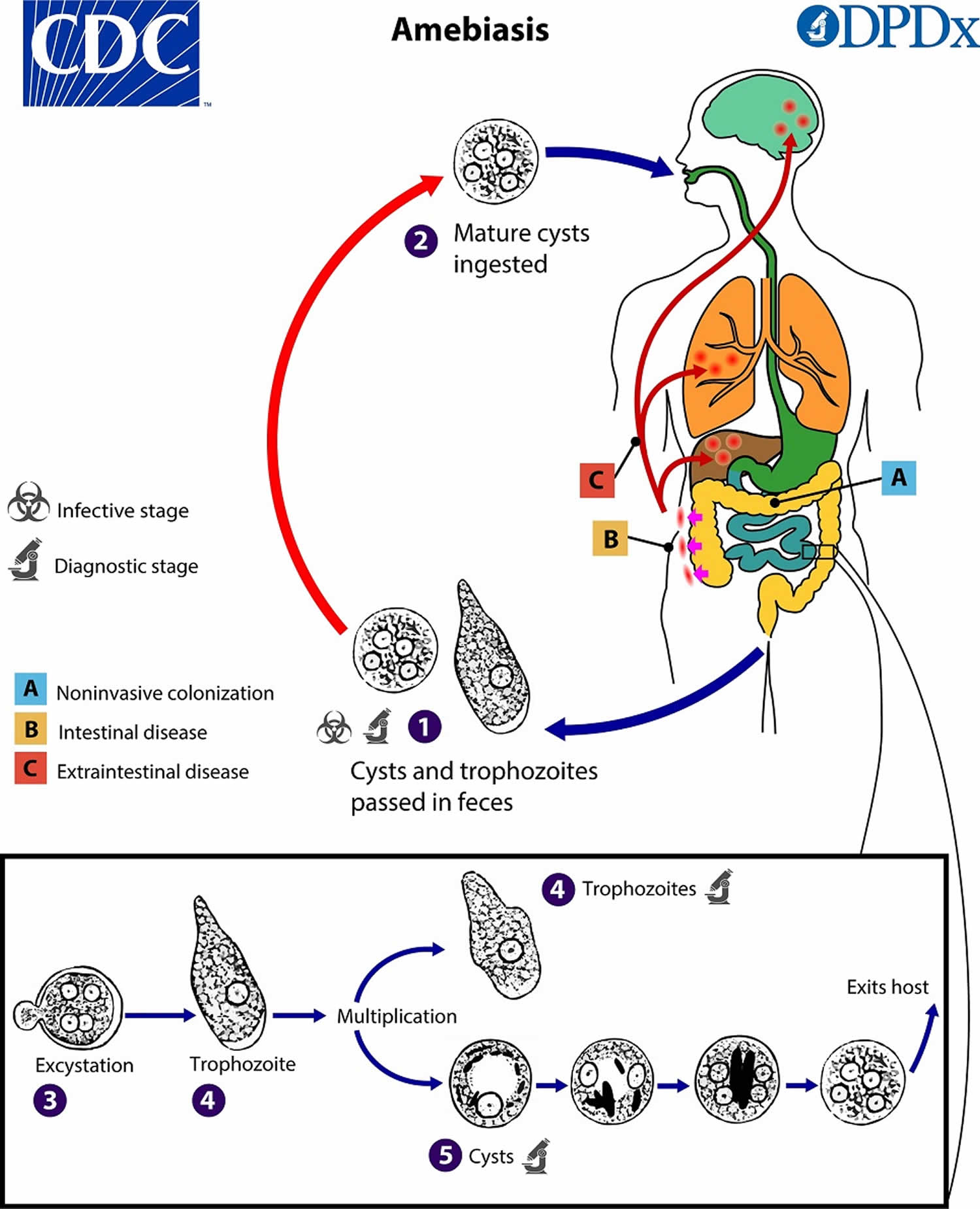

Amoebiasis causes

At least six different species of the genus Entamoeba can be found in human intestinal lumen, but not all of them are associated with amoebiasis disease 9. Entamoeba histolytica is well recognized as a pathogenic ameba, associated with intestinal and extraintestinal amoebiasis. Other morphologically-identical Entamoeba species, including Entamoeba dispar, Entamoeba moshkovskii and Entamoeba bangladeshi, are generally not associated with disease although investigations into their pathogenic potential are ongoing. These organisms are spread via the oral-fecal route. The infected cysts are often found in contaminated food and water (see Amoebiasis life cycle in Figure 3 below). Rare cases of sexual spread have also been reported.

Entamoeba histolytica can live in the large intestine (colon) without causing damage to the intestine. In some cases, it invades the colon wall, causing colitis, acute dysentery, or long-term (chronic) diarrhea. Amoebiasis infection can also spread through the bloodstream to the liver. In rare cases, it can spread to the lungs, brain, or other organs.

Amoebiasis occurs worldwide. It is most common in tropical areas that have crowded living conditions and poor sanitation. Africa, Mexico, parts of South America, and India have major health problems due to amoebiasis.

Entamoeba histolytica parasite may spread:

- Through food or water contaminated with stools

- Through fertilizer made of human waste

- From person to person, particularly by contact with the mouth or rectal area of an infected person

The principal source of amoebiasis is ingestion of water or food contaminated by feces containing mature E. histolytica cysts. Hence, travelers to developing countries can acquire amebiasis when visiting the endemic region. Those who are institutionalized or immunocompromised are also at risk. The organism E. histolytica is viable for prolonged periods in the cystic form in the environment. It can also be acquired after direct inoculation of the rectum, from anal or oral sex, or from equipment used for colonic irrigation.

In the United States, amebiasis is most common among those who live in institutions or people who have traveled to an area where amebiasis is common.

Risk factors for severe amebiasis

Risk factors for severe amebiasis include:

- Alcohol use

- Cancer

- Malnutrition

- Older or younger age

- Pregnancy

- Recent travel to a tropical region

- Use of corticosteroid medicine to suppress the immune system

Amoebiasis life cycle

Cysts and trophozoites are passed in feces (number 1). Cysts are typically found in formed stool, whereas trophozoites are typically found in diarrheal stool. Infection with Entamoeba histolytica (and Entamoeba dispar) occurs via ingestion of mature cysts (number 2) from fecally-contaminated food, water, or hands. Exposure to infectious cysts and trophozoites in fecal matter during sexual contact may also occur. Excystation of the mature cysts (number 3) occurs in the small intestine and trophozoites (number 4) are released, which then migrate to the large intestine (colon). Trophozoites may remain confined to the intestinal lumen (A: noninvasive infection) with individuals continuing to pass cysts in their stool (asymptomatic carriers). Trophozoites can invade the intestinal mucosa (B: intestinal disease), or blood vessels, reaching extraintestinal sites such as the liver, brain, and lungs (C: extraintestinal disease). Trophozoites multiply by binary fission and produce cysts (number 5) and both stages are passed in the feces (number 1). Cysts can survive days to weeks in the external environment because of the protection provided by the cyst wall and remain infectious in the environment. The cyst is responsible for further transmission of the parasite. Ingestion of only a small number of mature cysts can cause disease. Trophozoites passed in the stool are rapidly destroyed once outside the body, and if ingested would not survive exposure to the gastric environment.

Figure 3. Amoebiasis life cycle

[Source 10 ]Amoebiasis prevention

When traveling in countries where sanitation is poor, drink purified or boiled water. Do not eat uncooked vegetables or unpeeled fruit. Wash your hands after using the bathroom and before eating. Avoid fecal exposure during sexual activity. Prevention of amoebiasis is also by improved sanitation.

The following items are safe to drink:

- Bottled water with an unbroken seal

- Tap water that has been boiled for at least 1 minute

- Carbonated (bubbly) water from sealed cans or bottles

- Carbonated (bubbly) drinks (like soda) from sealed cans or bottles

You can also make tap water safe for drinking by filtering it through an “absolute 1 micron or less” filter and dissolving chlorine, chlorine dioxide, or iodine tablets in the filtered water. “Absolute 1 micron” filters can be found in camping/outdoor supply stores.

The following items may NOT be safe to drink or eat:

- Fountain drinks or any drinks with ice cubes

- Fresh fruit or vegetables that you did not peel yourself

- Milk, cheese, or dairy products that may not have been pasteurized.

- Food or drinks sold by street vendors

Amoebiasis signs and symptoms

Although most cases of amebiasis do not have symptoms (asymptomatic), about 10% to 20% of people who are infected with E. histolytica become sick from the infection and present with a spectrum of illness. The reasons for this are poorly understood but result from an interplay of several factors related to parasite, host, and environment 4. Recently, it was found that the gut microbiome is enriched in Prevotella copri in people with amebic diarrhea, indicating that dysbiosis may in part contribute to susceptibility to the development of colitis 11.

The incubation period from amebiasis is between 2 to 4 weeks.

Mild amebiasis symptoms may include:

- Abdominal cramps

- Diarrhea: passage of 3 to 8 semiformed stools per day, or passage of soft stools with mucus and occasional blood

- Fatigue

- Excessive gas

- Rectal pain while having a bowel movement (tenesmus)

- Unintentional weight loss

Severe amebiasis symptoms may include:

- Abdominal tenderness

- Bloody stools, including passage of liquid stools with streaks of blood, passage of 10 to 20 stools per day

- Fever

- Vomiting

Most patients with amoebiasis or amoebic dysentery have a gradual illness onset days or weeks after infection. Symptoms include mild abdominal cramps, watery diarrhea to severe colitis producing bloody diarrhea with mucus, and weight loss, and may last several weeks. Amebic colitis or invasive intestinal amebiasis, occurs when the intestinal mucosa is invaded. Symptoms include severe dysentery and associated complications. Dysentery is an infection of the intestines that causes diarrhea containing blood or mucus, painful stomach cramps, feeling sick or being sick (vomiting) and a high temperature. Risk factors include the use of corticosteroids, poor nutrition, young age, and pregnancy. Toxic megacolon can be a complication and is associated with very high mortality.

Young people tend to have a more severe disease compared to older individuals. Severe chronic amoebiasis may lead to further complications such as peritonitis, perforations, and the formation of amebic granulomas (ameboma).

Occasionally, the Entamoeba histolytica parasite may spread to other organs (extraintestinal amebiasis), most commonly the liver. The most common extraintestinal manifestations are an amoebic liver abscess. A liver abscess develops in less than 4% of patients and may occur within 2 to 4 weeks after the initial infection 2. For poorly understood reasons, amebic liver abscesses are 10 times more common in men than women, often presenting between the ages of 20 and 40 years 4. Amebic liver abscesses may be asymptomatic, but most patients present with fever, right upper quadrant abdominal pain and tenderness to palpation, and weight loss, usually in the absence of diarrhea.

An amoebic liver abscess may rupture into the pleural cavity or pericardium, presenting as pleural or pericardial effusion; however, this is a rare occurrence. Rarely, amebiasis may affect the heart, brain, kidneys, spleen, and skin. One can also develop proctocolitis, toxic megacolon, peritonitis, pleuropulmonary abscess, pericarditis, brain abscess, and necrotic lesions on the perianal skin and genitalia. Hence, amebiasis is a leading parasitic cause of death in humans.

Amebic liver abscess

Amebic liver abscess is a collection of pus in the liver caused by Entamoeba histolytica parasite. After Entamoeba histolytica infection has occurred, the parasite may be carried by the bloodstream from the intestines to the liver.

Risk factors for amebic liver abscess include 12:

- Recent travel to a tropical region

- Alcoholism

- Cancer

- Immunosuppression, including HIV/AIDS infection

- Malnutrition

- Old age

- Pregnancy

- Steroid use

Amebic liver abscess symptoms

There are usually no symptoms of intestinal amebiasis. But people with amebic liver abscess do have symptoms, including:

- Abdominal pain, more so in the right, upper part of the abdomen; pain is intense, continuous or stabbing

- Cough

- Fever and chills

- Diarrhea, non-bloody (in only one-third of people with amebic liver abscess)

- General discomfort, uneasiness, or ill feeling (malaise)

- Hiccups that do not stop (rare)

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin, mucous membranes, or eyes)

- Loss of appetite

- Sweating

- Weight loss

Amoebiasis complications

Complications of amebiasis may include:

- Spread of the amoeba parasite through the blood to the liver, lungs, brain, or other organs

- Toxic megacolon

- Fulminant necrotizing colitis

- Rectovaginal fistula

- Ameboma

- Liver abscess (collection of pus in the liver)

- Intraperitoneal rupture of liver abscess

- Secondary bacterial infection

- Extension of infection from the liver into the pericardium or pleura

- Dissemination in the brain

- Bowel perforation

- Stricture of the colon

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

- Empyema (pockets of pus that have collected inside the pleural cavity)

Amoebiasis diagnosis

Your health care provider will perform a physical examination. You’ll be asked about your symptoms and recent travel. Tests that may be done include:

- Abdominal ultrasound

- Abdominal CT scan or MRI

- Complete blood count

- Liver abscess aspiration to check for bacterial infection in the liver abscess

- Liver scan

- Liver function tests

- Blood test for amebiasis

- Stool testing for amebiasis. Because E. histolytica is not always found in every stool sample, you may be asked to submit several stool samples from several different days.

Table 1. Comparison of laboratory diagnostic tests for amoebiasis

| Method | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | <60% 13 | – | Widely available | Poor sensitivity and specificity; cannot differentiate from other Entamoeba spp. |

| Screens for other parasites | Multiple stools need to be submitted | |||

| Minimal equipment and reagents required | Skilled observer required; time-consuming | |||

| Serology | 65%–92% 14 | >90% 14 | High sensitivity and specificity, useful adjunct to stool studies | Serology remains positive for years after resolution of infection, so less helpful in endemic areas; more useful in travelers |

| Rapid turnaround | Antibody response is often detectable by the time of presentation but may need to be repeated in 7–10 days if initially negative | |||

| Stool antigen detection | 0%–88% 15 | >80% 15 | May have high sensitivity in endemic areas but reduced sensitivity in nonendemic areas | Poor sensitivity for amebic liver abscess |

| Simple to perform, rapid turnaround time, and commercially available combined tests exist to detect several enteroparasites | Requires fresh, not fixative preserved stool for analysis | |||

| Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) | 92%–100% 15 | 89%–100% 15 | Gold standard; high sensitivity and specificity for colitis and liver abscess with increasing availability | More expensive; cost may limit use in resource-limited settings |

| Rapid turnaround; automated systems reduce technician time and risk of contamination | Requires analysis instruments, kits, and skilled technician | |||

| Can be combined with multiplex panels to detect multiple enteric pathogens at a time |

Amebiasis can be diagnosed by a demonstration of the E. histolytica cyst and/or the trophozoite stages of the parasite using direct microscopy of stool samples or rectal swabs 9. However, the organisms are seen in only 30% of patients and microscopy does not distinguish between Entamoeba histolytica (known to be pathogenic), Entamoeba bangladeshi, Entamoeba dispar, and Entamoeba moshkovskii. E. dispar and E. moshkovskii have historically been considered nonpathogenic, but evidence is mounting that Entamoeba moshkovskii can cause illness; Entamoeba bangladeshi has only recently been identified, so its pathogenic potential is not well understood 1. More specific tests such as antigen detection using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are needed to confirm the diagnosis of E. histolytica 9. Additionally, serologic tests can help diagnose extraintestinal amebiasis. Antibody detection is most useful in patients with extraintestinal disease (i.e., amebic liver abscess) when organisms are not generally found on stool examination. Antibody detection is of limited diagnostic value on patients from highly endemic areas that are likely to have prior exposure and seroconversion, but may be of more use on patients from areas where pathogenic Entamoeba spp. are rare. However, the most promising detection method is the loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay because of its rapidity, operational simplicity, high specificity, and sensitivity.

Colonoscopy combined with biopsy or intestinal fluid sample collection can be useful in distinguishing amebic colitis from other colonic entities 8. Colonoscopy is appropriate when the stool studies are negative for amebiasis. The mucosal appearance of amebic colitis on endoscopy may be grossly indistinguishable from that of intestinal tuberculosis, other forms of infectious colitis and inflammatory bowel disease 16. Common but nonspecific endoscopic findings include diffusely inflamed and friable mucosa 17. Histology of the intestinal infection is nonspecific. It usually reveals discrete ulcers, mucosal thickening, edematous mucosa, acute and/or chronic inflammation with amebic trophozoites invading through the bowel wall 18. Sometimes flask-shaped ulcers may be seen in the submucosal layers. In some patients, flask-shaped ulcers are seen.

Blood tests may reveal the following:

- Elevated white blood cells (WBC)

- Eosinophilia

- Elevated bilirubin and transaminase enzymes

- Mild anemia

- Elevated ESR

Imaging studies may be required depending on the presentation. An ultrasound or CT scan can identify a liver abscess 3.

Liver aspiration using CT-guided imaging is often performed when there is a collection in the liver. The liver aspiration usually reveals a chocolate-like or thick, dark viscous fluid. Liver aspiration is indicated when the abscess is large, or there is a threat of imminent rupture.

Cultures can be done from fecal or rectal biopsy specimens or liver aspirates. Cultures are not always positive, with a success rate of about 60%.

Stool microscopy

Entamoeba histolytica cysts and trophozoites can be visualized by an experienced eye, sometimes with evidence of hemophagocytosis. Fresh stools increase the recovery of both trophozoites and cysts and can be prepared as either wet mounts or stained preparations. Mature cysts have 4 nuclei measuring about 12–15 µm in diameter. Trophozoites have a single nucleus and are slightly larger, measuring about 15–20 µm. Microscopy should not be used when other modalities are accessible.

Stool antigen detection

Antigen detection tests have helped to overcome some of the limitations of stool microscopy and are easy to use, but in practice have variable sensitivity and specificity, particularly in low-endemic areas 19. Although several enzyme immune assay (EIA) kits are commercially available, they are not as widely available in resource-limited settings. The Techlab E. histolytica II test (Blacksburg, VA), which detects E. histolytica–derived Gal/GalNAc-specific lectin, can exclude nonpathogenic E. dispar, as can the Cellabs CELISA Path (Brookvale, Australia). A false-negative EIA test was reported from Spain, possibly from interference, as the result turned positive with subsequent testing 20. Recently, an E. HISTOLYTICA QUIK CHEK immunochromatographic assay, which is simple to perform and has a quick turnaround time, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Stool molecular studies

Stool PCR is extremely sensitive. It is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of amebiasis and is becoming readily available through FDA-cleared gastrointestinal panels that simultaneously detect multiple enteropathogens, such as the BD Max Enteric Parasite Panel (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD), the Luminex xTAG Gastrointestinal Pathogen Panel (Luminex Corporation, Toronto, Canada), and the Biofire FilmArray Gastrointestinal Panel (BioFire Diagnostics, Salt Lake City, UT) 15. The use of PCR is also endorsed by the World Health Organization, but the expense and requirement for technical expertise may limit use in resource-limited settings 21. Purulent fluid aspirated from liver abscess can also be tested.

Serology

Serology is a useful adjunct to stool studies. Several EIA kits for antibody detection are commercially available, including indirect fluorescence, immunoelectrophoresis, and immunosorbent assays, but the indirect hemagglutination test has been replaced by EIA. Antibody detection is particularly helpful in the diagnosis of extra-intestinal disease, when stool studies may be negative. False-positive results have been reported 22. Antibodies remain detectable for years after successful treatment, so it is difficult to reliably distinguish between active and past infection.

Imaging studies

Ultrasonography, abdominal computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging are all good modalities to detect liver abscess. By ultrasound, a cystic intrahepatic hypoechoic lesion can be found. By CT, an abscess with a nonenhancing center surrounded by a rim of inflammation can be seen following contrast administration. The detection of a space-occupying lesion in the liver and positive amebic serology supports the diagnosis of amebic liver abscess.

Other diagnostic methods

Amebic ulcers most often develop in the cecum. Histology obtained by diagnostic endoscopic biopsy or surgical resection may show the characteristic flask-shaped ulcer. Trophozoites may be identified at the edge of the ulcer or within the tissue, using periodic acid-Schiff staining or immunoperoxidase staining with specific anti-E. histolytica antibodies.

Amebiasis treatment

The primary treatment for symptomatic amebiasis requires hydration and the use of antibiotics such as metronidazole (Flagyl) and/or tinidazole (Tindamax). The amebicidal agents, metronidazole and tinidazole, are highly effective at eliminating invading trophozoites and remain the recommended therapy for amebic colitis and amebic liver disease 4. Tinidazole has a longer half-life and is better tolerated, but metronidazole is as effective at clearing parasites 23. Side effects of metronidazole include nausea, headache, anorexia, metallic taste, peripheral neuropathy, and disulfiram-like reaction with alcohol. The nitroimidazoles (metronidazole and tinidazole) do not effectively eradicate luminal Entamoeba histolytica cysts and must be followed by a luminal agent. The thiazolide agent nitazoxanide, with reputed broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties, was shown in a small single-center trial from Egypt to have clinical and microbiologic response in patients treated for hepatic and intestinal amebiasis of >90%. However, the unexpectedly high response rate in the placebo group of 40%–50% raises methodologic concerns 24.

These two amebicidal tissue-active agents are dosed as follows:

- Metronidazole dosing for adults is 500 mg orally every 6 to 8 hours for 7 to 14 days.

- Tinidazole adult dosing is 2 g orally each day for 3 days.

Luminal cysticidal agents such as paromomycin and diloxanide furoate are also used to get rid of all the amoeba in the intestine and to prevent the disease from coming back. This treatment can usually wait until after the abscess has been treated. As paromomycin may cause diarrhea, it should not be administered at the same time as the nitroimidazole agent (metronidazole, tinidazole). Diloxanide and iodoquinol are alternatives, but neither is available in the United States.

If you are vomiting, you may be given medicines through a vein (intravenously) until you can take them by mouth. Medicines to stop diarrhea are usually not prescribed because they can make the condition worse.

Patients with fulminant amebic colitis will additionally require fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy for peritonitis, intensive supportive care, and surgical intervention for bowel perforation and bowel necrosis. Occasionally, colectomy has been necessitated by the development of toxic megacolon or extensive bowel necrosis 13. In patients who are unable to tolerate or absorb oral metronidazole, intravenous metronidazole should be used 25.

After antibiotic treatment, your stool will likely be rechecked to make sure the infection has been cleared.

An amoebic liver abscess can be managed by aspiration using CT guidance in combination with metronidazole. Surgery is sometimes required to treat massive gastrointestinal bleeding, toxic megacolon, perforated colon, or liver abscesses not amenable to percutaneous drainage 26. In rare cases, amoebic liver abscess may need to be drained using a catheter or surgery to relieve some of the abdominal pain and to increase chances of treatment success. Drainage is typically reserved for those who do not show prompt clinical response to antiparasitic therapy by about 72 hours or those at high risk for impending abscess rupture, typically defined by a cavity with a diameter >5–10 cm or by left lobe abscess, which could rupture into the pericardium. Serial imaging may show that it takes months following appropriate therapy for the abscess cavity to resolve 22.

Table 2. Antiparasitic therapy for Entamoeba histolytica infection

| Drug of Choice | Daily Dose | Duration d | Alternatives | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amebicidal tissue-active agent | ||||

| Amebic colitis a | Metronidazole or | 750 mg orally three times daily (35–50 mg/kg/day divided three times daily) | 5–10 | Nitazoxanide b |

| Tinidazole | 2 g orally once daily (50 mg/kg once daily) | 3–5 | ||

| Amebic liver abscess and disseminated amebic disease a | Metronidazole or | 750 mg orally three times daily (35–50 mg/kg/day divided three times daily) | 10 | – |

| Tinidazole | 2 g orally once daily (50 mg/kg once daily) | 5 | ||

| Luminal agent | ||||

| Asymptomatic carriage or following tissue-active agent | Paromomycin | 25–35 mg/kg/day by mouth divided three times daily | 7 | Iodoquinol/diiodohydroxyquin diloxanide furoate c |

Footnotes:

a Severe disease or unable to tolerate oral therapy, use metronidazole 1500 mg intravenous (IV) divided three times daily (7.5–30 mg/kg/day divided three times daily) 25.

b Limited data, 500 mg orally twice daily (≥12 years), 200 mg twice daily (age 4–11 years), or 100 mg twice daily (age 1–3 years) for 3 days.

c Iodoquinol 650 mg orally three times daily (30–40 mg/kg/day orally divided three times daily for children) for 20 days after meals (optic neuritis and peripheral neuropathy have been reported), diloxanide furoate 500 mg orally three times daily (20 mg/kg/day orally divided three times daily for children) for 10 days 27.

[Source 4 ]Amoebiasis prognosis

If left untreated, amoebic infections have very high morbidity and mortality (death rate). In fact, mortality is second only to malaria. Amoebic infections tend to be most severe in the following populations:

- Pregnant women

- Postpartum women

- Neonates

- Malnourished individuals

- Individuals who are on corticosteroids

- Individuals with malignancies

When amoebiasis is treated, the prognosis is good, the illness lasts about 2 weeks, but recurrent infections are common in some parts of the world. Amoebiasis mortality rates after treatment are less than 1%. However, amoebic liver abscesses may be complicated by an intraperitoneal rupture in 5% to 10% of cases, potentially increasing the mortality rate. Amoebic pericarditis and pulmonary amebiasis have a high mortality rate exceeding 20%.

Today with effective treatment, mortality rates are less than 1% in patients with uncomplicated amoebiasis. However, rupture of an infected amebic liver abscess carries a high mortality.

Without treatment, amebic liver abscess may break open (rupture) into the abdominal cavity, the lining of the lungs, the lungs, or the sac around the heart, leading to death. The infection can also spread to the brain. People with amebic liver abscess who are treated have a very high chance of a complete cure or only minor complications.

References- Amebiasis. Chapter 4 Travel-Related Infectious Diseases. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/travel-related-infectious-diseases/amebiasis

- Zulfiqar H, Mathew G, Horrall S. Amebiasis. [Updated 2022 Jan 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519535

- Saidin S, Othman N, Noordin R. Update on laboratory diagnosis of amoebiasis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019 Jan;38(1):15-38. doi: 10.1007/s10096-018-3379-3

- Shirley, D. T., Farr, L., Watanabe, K., & Moonah, S. (2018). A Review of the Global Burden, New Diagnostics, and Current Therapeutics for Amebiasis. Open forum infectious diseases, 5(7), ofy161. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofy161

- Greenstein AJ, Lowenthal D, Hammer GS, Schaffner F, Aufses AH Jr. Continuing changing patterns of disease in pyogenic liver abscess: a study of 38 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984 Mar;79(3):217-26.

- Kumanan, T., Sujanitha, V., Balakumar, S., & Sreeharan, N. (2018). Amoebic Liver Abscess and Indigenous Alcoholic Beverages in the Tropics. Journal of tropical medicine, 2018, 6901751. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6901751

- Kelsall BL, Ravdin JI. Amebiasis: human infection with Entamoeba histolytica. Prog Clin Parasitol. 1994;4:27-54.

- Fleming, R., Cooper, C. J., Ramirez-Vega, R., Huerta-Alardin, A., Boman, D., & Zuckerman, M. J. (2015). Clinical manifestations and endoscopic findings of amebic colitis in a United States-Mexico border city: a case series. BMC research notes, 8, 781. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1787-3

- Guevara, Á., Vicuña, Y., Costales, D., Vivero, S., Anselmi, M., Bisoffi, Z., & Formenti, F. (2019). Use of Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction to Differentiate between Pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica and the Nonpathogenic Entamoeba dispar in Ecuador. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 100(1), 81–82. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.17-1022

- Amebiasis. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/amebiasis/index.html

- Ngobeni, R., Samie, A., Moonah, S., Watanabe, K., Petri, W. A., Jr, & Gilchrist, C. (2017). Entamoeba Species in South Africa: Correlations With the Host Microbiome, Parasite Burdens, and First Description of Entamoeba bangladeshi Outside of Asia. The Journal of infectious diseases, 216(12), 1592–1600. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jix535

- Amebic liver abscess. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000211.htm

- Shirley, D. A., & Moonah, S. (2016). Fulminant Amebic Colitis after Corticosteroid Therapy: A Systematic Review. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 10(7), e0004879. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004879

- Alvarado-Esquivel, C., Hernandez-Tinoco, J., & Sanchez-Anguiano, L. F. (2015). Seroepidemiology of Entamoeba histolytica Infection in General Population in Rural Durango, Mexico. Journal of clinical medicine research, 7(6), 435–439. https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr2131w

- Ryan U, Paparini A, Oskam C. New Technologies for Detection of Enteric Parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2017 Jul;33(7):532-546. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2017.03.005

- Nagata N, Shimbo T, Akiyama J, Nakashima R, Niikura R, Nishimura S, Yada T, Watanabe K, Oka S, Uemura N. Predictive value of endoscopic findings in the diagnosis of active intestinal amebiasis. Endoscopy. 2012 Apr;44(4):425-8. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291631

- Pittman FE, Hennigar GR. Sigmoidoscopic and colonic mucosal biopsy findings in amebic colitis. Arch Pathol. 1974 Mar;97(3):155-8.

- Takahashi T, Gamboa-Dominguez A, Gomez-Mendez TJ, Remes JM, Rembis V, Martinez-Gonzalez D, Gutierrez-Saldivar J, Morales JC, Granados J, Sierra-Madero J. Fulminant amebic colitis: analysis of 55 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997 Nov;40(11):1362-7. doi: 10.1007/BF02050824

- Stark, D., van Hal, S., Fotedar, R., Butcher, A., Marriott, D., Ellis, J., & Harkness, J. (2008). Comparison of stool antigen detection kits to PCR for diagnosis of amebiasis. Journal of clinical microbiology, 46(5), 1678–1681. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02261-07

- Prim N, Escamilla P, Solé R, Llovet T, Soriano G, Muñoz C. Risk of underdiagnosing amebic dysentery due to false-negative Entamoeba histolytica antigen detection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012 Aug;73(4):372-3. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.04.012

- Qvarnstrom, Y., James, C., Xayavong, M., Holloway, B. P., Visvesvara, G. S., Sriram, R., & da Silva, A. J. (2005). Comparison of real-time PCR protocols for differential laboratory diagnosis of amebiasis. Journal of clinical microbiology, 43(11), 5491–5497. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.43.11.5491-5497.2005

- Cordel, H., Prendki, V., Madec, Y., Houze, S., Paris, L., Bourée, P., Caumes, E., Matheron, S., Bouchaud, O., & ALA Study Group (2013). Imported amoebic liver abscess in France. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 7(8), e2333. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002333

- Gonzales ML, Dans LF, Martinez EG. Antiamoebic drugs for treating amoebic colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Apr 15;(2):CD006085. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006085.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jan 09;1:CD006085

- Rossignol JF, Kabil SM, El-Gohary Y, Younis AM. Nitazoxanide in the treatment of amoebiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007 Oct;101(10):1025-31. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.04.001

- Kimura M, Nakamura T, Nawa Y. Experience with intravenous metronidazole to treat moderate-to-severe amebiasis in Japan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007 Aug;77(2):381-5.

- González-Alcaide, G., Peris, J., & Ramos, J. M. (2017). Areas of research and clinical approaches to the study of liver abscess. World journal of gastroenterology, 23(2), 357–365. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i2.357

- Abramowicz J, ed. Drugs for Parasitic Infections. 2nd ed New Rochelle, NY: The Medical Letter; 2010.