Anterior talofibular ligament tear

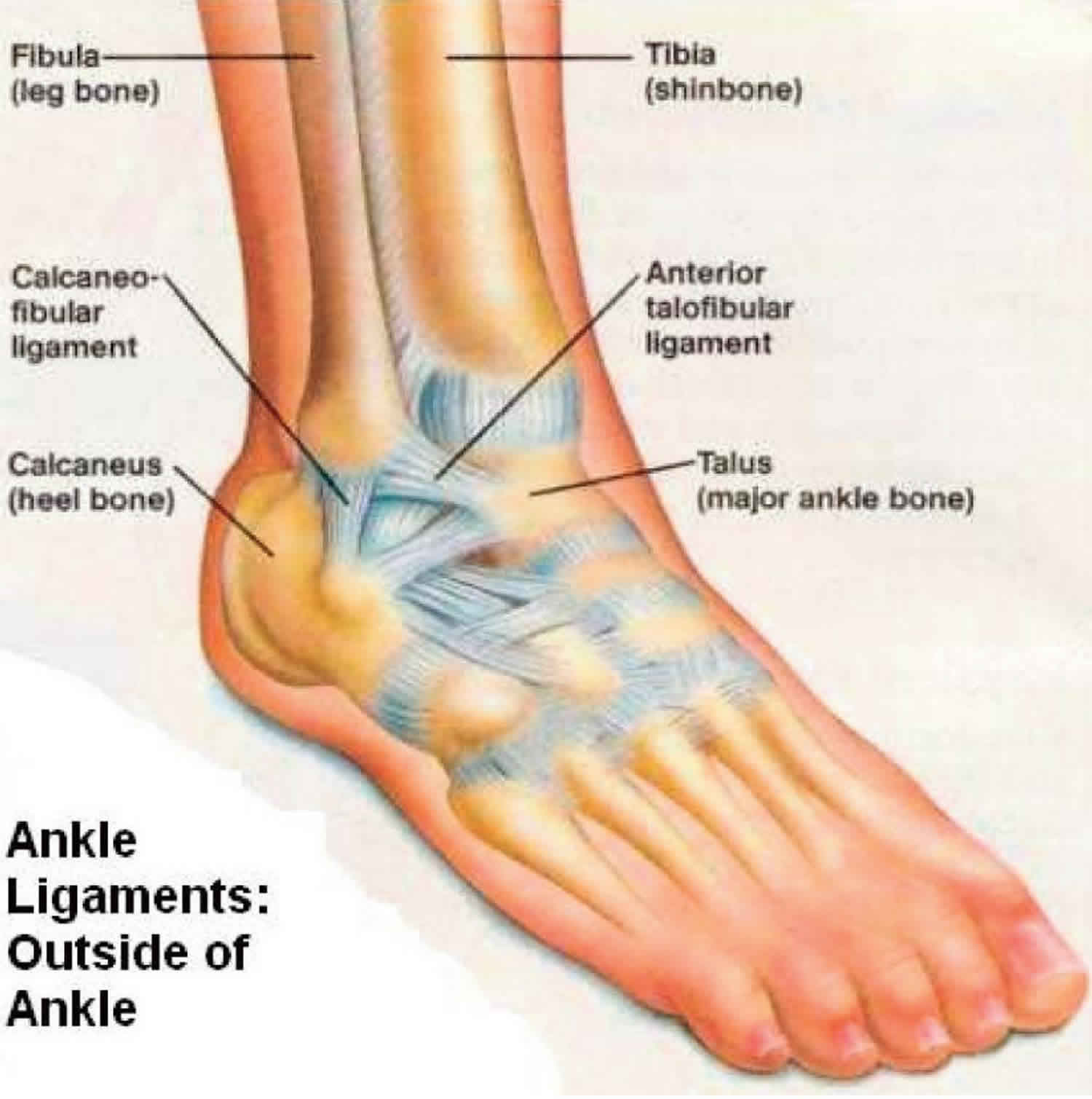

Anterior talofibular ligament tear is most commonly seen in sprained ankle with an inversion injury to the ankle, either with or without plantar flexion 1. If associated bony avulsion, it is mostly at the fibular malleolus rather than the talar end of the anterior talofibular ligament with characteristic bright rim sign. The anterior talofibular ligament is one of the lateral stabilizing ligaments of the ankle and it is the weakest of the lateral collateral ligament complex, is the most commonly injured ligament in ankle inversion injuries 2. From the anatomic viewpoint, anterior talofibular ligament is a flat quadrilateral ligament that originates from the inferior oblique segment of the anterior border of the lateral malleolus and inserts into the talar body just anterior to the lateral malleolar articular surface of the talus. According to anatomic literature 3, most anterior talofibular ligaments consist of two or more bands. According to biomechanical studies, the anterior talofibular ligament is the weakest lateral ankle ligament, followed by the calcaneofibular ligament 4. Although most ankle sprains are treated conservatively with functional rehabilitation or an Aircast or Air-Stirrup ankle brace 5, for persistent or residual ankle disability, surgical approaches, such as reapproximation of the torn ligament or reconstruction of the ligament repair may be considered as treatment options 6.

Sprained ankles are common injuries, approximately 5000 and 27000 new cases are reported daily in the UK and USA, respectively 7. Although they can occur in everyday life, they are particularly characteristic of sports such as basketball and soccer 8. Most ankle sprains affect the anterior talofibular ligament, which is the weakest component of the lateral ligament complex of the ankle joint. When the foot is in the anatomical position, the anterior talofibular ligament runs approximately horizontally, but when it is plantarflexed, the ligament is nearly parallel to the long axis of the leg. It is only in the latter position that the ligament comes under strain and is vulnerable to injury, particularly when the foot is inverted 9.

According to Broström 10 and Linstrand 11, approximately two-thirds of ankle sprains are isolated injuries to the anterior talofibular ligament. The injuries may be soft tissue tears or avulsion fractures 10. There is general agreement that avulsion is more common at the fibular than the talar end of the ligament 12, but the reason for this is unclear. Paradoxically, laboratory tests on isolated bone–ligament–bone samples show that avulsions are more common at the talar end 13.

Anterior tibiofibular ligament anatomy

The lateral articular capsule of the ankle can be divided into anterior and posterior segments. The anterior segment attaches proximally to the anterior portion of the distal tibia superior to the articular surface and to the border of the articular surface of the medial malleolus. The posterior segment attaches distally to the talus just posterior to its superior articular facet and attaches laterally to the depression in the medial surface of the lateral malleolus 14.

The anterior tibiofibular ligament is intracapsular and attaches anteriorly to the anterior border of the distal fibula and laterally to the neck of the talus. The posterior tibiofibular ligament attaches posteriorly to the digital fossa of the fibula and laterally to the lateral tubercle on the posterior portion of the talus.

The talofibular ligaments along with the calcaneofibular ligament are components of the lateral ligament complex. This complex becomes stressed when the ankle is inverted and plantar flexed 15. Supination of the foot in neutral flexion usually results in injury of the calcaneofibular ligament. Supination and adduction injuries tear both the anterior talofibular ligament and the calcaneofibular ligament.

The posterior tibiofibular ligament is the strongest of the lateral ligaments, and extreme inversion with plantar flexion is required to place the posterior tibiofibular ligament under stress; as a result, the posterior tibiofibular ligament is less commonly injured 15. Transient subluxation or dislocation of the talus from the tibial mortise usually results in injury of all 3 lateral ligaments. Prevention of anterior displacement of the talus is primarily a function of the anterior talofibular ligament. Little additional motion occurs when the calcaneofibular ligament also is damaged. Instability to inversion is greater when both the calcaneofibular ligament and the anterior talofibular ligament are injured than when either ligament is injured alone.

Anterior talofibular ligament injury grading

AMA classification 16:

- Grade 1: ligament stretch

- Grade 2:

- partial tear

- partial loss of movement

- mild to moderate joint instability

- Grade 3:

- complete tear

- inability to bear weight

- significant joint instability

Many orthopedists favor a functional approach based on clinical examination:

- Grade 1: stable injury

- provocative maneuvers do not elicit increased upper ankle joint laxity

- no ligament in the lateral complex is completely ruptured

- Grade 2: unstable

- ruptured anterior tibiofibular ligament

- increased upper ankle joint laxity

- Grade 3: unstable

- ruptured calcaneofibular ligament

- increased upper ankle joint laxity

There are other grading systems, of course, such as the anatomic classification or grading by clinical presentation symptoms 17.

Figure 1. Sprained ankle grades

Anterior talofibular ligament tear causes

Anterior talofibular ligament injuries typically occur with an inversion injury to the ankle, either with or without plantar flexion. Approximately two-thirds of ankle sprains tend to be isolated injuries to the anterior talofibular ligament (the anterior talofibular ligament is the weakest ligament in the lateral collateral complex of the ankle). There is general agreement that avulsion is more common at the fibular than the talar end of the ligament 18.

Anterior talofibular ligament tear prevention

It’s impossible to prevent all ankle sprains. But everyone can take precautions to make sprains less likely.

The best way to prevent ankle sprains is keeping your ankles flexible and your leg muscles strong. Your coach, doctor, or PE teacher can give you some easy at-home exercises to build muscle strength (which protects ligaments) and joint flexibility.

Here are some other ways to protect yourself against ankle sprains:

- Always warm up and use the recommended stretching techniques for your ankles before playing sports, exercising, or doing any other kind of physical activity.

- Watch your step when you’re walking or running on uneven or cracked surfaces.

- Don’t overdo things. If you’re tired or fatigued, it can make an injury more likely. Slow down, stop what you’re doing, or take extra care to watch your step when you’re tired.

- If you’ve had a sprained ankle in the past, make sure it’s completely healed before you try any strenuous physical activities.

- Using tape, ankle braces, or high-top shoes may be helpful if you’re prone to ankle sprains.

- Get good shoes that fit your feet correctly, and keep them securely tied or fastened when you’re wearing them. Speaking of shoes, one of the biggest causes of ankle sprains in women is wearing high-heeled shoes.

Anterior talofibular ligament tear symptoms

It’s likely to be a sprain ankle or anterior talofibular ligament tear if:

- you have pain, tenderness or weakness – often around your ankle, foot, wrist, thumb, knee, leg or back

- the injured area is swollen or bruised

- you cannot put weight on the injury or use it normally

- you have muscle spasms or cramping – where your muscles painfully tighten on their own

Ligamentous injuries of the ankle are classified into the following 3 categories, depending on the extent of damage to the ligaments 19:

- Grade 1 is an injury without macroscopic tears. No mechanical instability is noted. Pain and tenderness is minimal.

- Grade 2 is a partial tear. Moderate pain and tenderness is present. Mild to moderate joint instability may be present.

- Grade 3 is a complete tear. Severe pain and tenderness, inability to bear weight, and significant joint instability are noted.

Physical examination

- Test the range of motion. Patients with ligamentous injuries, especially to the anterior talofibular ligament, will have limited and painful inversion of their ankle.

- Assess the stability of the ankle joint. The anterior drawer test assesses the stability of the lateral ligaments. To perform this test, the foot is placed in slight inversion and 20° of plantar flexion. The heel is grasped firmly and drawn forward by the examiner, while the tibia is stabilized by the examiner’s other hand. A positive sign occurs when the talus moves forward on the tibia. The injured side should also be tested for maximal inversion compared with the uninjured side. If the anterior talofibular ligament is torn, forward motion is detected on performing the anterior drawer test. If the anterior talofibular ligament and the calcaneofibular ligament are torn, abnormal inversion is elicited.

- Talar tilt test: Assess the stability of the calcaneofibular ligament. Grade 1 sprains are partial tears of the ligaments and are stable to stress testing. Grade 2 sprains have a mildly increased anterior drawer test and are stable to inversion. Grade 3 sprains are unstable to both the anterior drawer test and the talar tilt test. Instability with these tests indicates a complete tear of the anterior talofibular ligament and at least a partial tear of the calcaneofibular ligament.

- Perform a neurovascular examination of the foot distal to the injury. Document the findings.

- Perform a neurologic exam. This should include testing the patient’s balance. Have them stand on their uninjured foot, initially with their eyes open; then, have them close their eyes. Then have the patient do this with the injured foot and compare. Ankle injuries will often disrupt the nerves, causing the patient to have poor balance.

Anterior talofibular ligament tear diagnosis

Indications for imaging studies in cases of suspected talofibular ligament injuries include the following:

- Bony tenderness or deformity

- Suspicion of a fracture or syndesmotic injury

- Severe pain or swelling that makes the physical examination unreliable

- Inability to walk

Initial radiologic studies of the ankle should include the following:

- An anteroposterior (AP) view with the ankle in slight adduction

- A true lateral view

- A mortise view (45° oblique view with the ankle in dorsiflexion)

- Consider stress views of the ankle.

- If a syndesmotic injury is suspected, then AP and lateral views of the tibia and fibula should also be obtained to rule out associated fibular fractures.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful in evaluating the soft-tissue anatomy of the ankle, such as ligaments and tendons 20. This imaging modality is not typically an initial test performed, but MRI may be useful in the patient who is not healing, in whom a stress fracture is suspected, or in chronic ankle pain and instability.

A study with 25 participants reported that stress ultrasonography provides a safe, repeatable, and quantifiable method of measuring the talofibular interval and may augment manual stress examinations in acute ankle injuries 21.

Anterior talofibular ligament tear treatment

Initial treatment of all grades of lateral ankle sprains consists of rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE), as well as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) 20. Grade 2 sprains will benefit from wearing an elastic bandage or an air splint (a cushioned plastic brace). Grade 3 sprained ankle puts you at risk for permanent ankle instability. Rarely, surgery may be needed to repair the damage, especially in competitive athletes. For severe ankle sprains, your doctor may also consider treating you with a short leg cast for two to three weeks or a walking boot to help immobilize the ankle. People who sprain their ankle repeatedly may also need surgical repair to tighten their ligaments.

Even ankle ligaments that are completely torn can often heal on their own if they’re properly immobilized. On rare occasions, though, a sprained ankle may require surgery.

Doctors usually try immobilization and other treatments before recommending surgery. But if your doctor decides surgery is the best option, he or she may start with arthroscopy. This involves inserting a small camera device into the joint through a tiny cut. It allows the doctor to look inside the joint to see what’s going on — like if part of the ligament is caught in the joint or there are bone fragments in the joint — and treat it if necessary.

In very rare cases, doctors will recommend surgery to reconstruct a torn ligament.

For the first couple of days, follow the 4 steps known as RICE therapy to help bring down swelling and support the injury:

- Rest – stop any exercise or activities and try not to put any weight on the injury.

- Ice – apply an ice pack (or a bag of frozen vegetables wrapped in a tea towel) to the injury for up to 20 minutes every 2 to 3 hours to help reduce swelling for the first 48 hours after the injury. This should begin as soon as possible after the injury and then every 3 to 4 hours for 20 to 30 minutes at a time until the swelling is gone.

- Compression – wrap a bandage around the injury to support it. Your doctor may place your ankle in a splint, like an air splint, or an elastic wrap. Follow instructions closely and don’t remove these until your doc says it’s OK.

- Elevate – When you are sitting or lying down, keep your leg elevated.

To help prevent swelling, try to avoid heat (such as hot baths and heat packs), alcohol and massages for the first couple of days.

Take anti-inflammatory medications. Ibuprofen and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can help relieve pain and reduce swelling in the ankle.

Avoid activities that put pressure on your ankle. Don’t play sports that require running, cutting, or stopping quickly until your doc says it’s OK. Don’t hike, jog, or exercise on uneven surfaces until the ankle is properly healed.

When you can move the injured area without pain stopping you, try to keep moving it so the joint or muscle does not become stiff.

Do stretching and strengthening exercises. After the pain and swelling have improved, ask your doctor about an exercise program to improve your ankle’s strength and flexibility. Depending on the severity of the sprain, the doctor may recommend physical therapy to help the healing process.

After 2 weeks, most sprains and strains will feel better.

Avoid strenuous exercise such as running for up to 8 weeks, as there’s a risk of further damage.

In grade 3 ankle sprains, some studies have shown that early mobilization and rehabilitation may provide earlier functional recovery relative to surgery, and there is general agreement to try a 6-week period of conservative management, including early, controlled mobilization and rehabilitation before considering surgery 22.

Also, no difference is found in long-term outcome when comparing early surgical repair with delayed surgical repair following failed conservative therapy 22.Therefore, there is no indication for routine early surgical repair.

It is generally accepted that for most patients, operative repair of third-degree anterior talofibular ligament tears and medial ankle ligament tears does not contribute to an improved outcome 23.

In 100 patients with isolated lateral ligament sprains, Evans et al 24 found no functional or symptomatic advantage 2 years after injury in patients who were treated surgically as compared with those who were treated with cast immobilization. In fact, the nonsurgically treated group returned to work earlier and had less morbidity than the surgically treated patients. Patients in this study were divided into two groups, each with 30 individuals with anterior ligament sprains only and 20 individuals with anterior and middle ligament ruptures. One group of 50 patients was treated surgically, and the other group was treated with cast immobilization.

Severe sprains and strains can take months to get back to normal.

Rehabilitation

Every ligament injury needs rehabilitation. Otherwise, your sprained ankle might not heal completely and you might re-injure it. All ankle sprains, from mild to severe, require three phases of recovery:

- Phase 1 includes resting, protecting and reducing swelling of your injured ankle.

- Phase 2 includes restoring your ankle’s flexibility, range of motion and strength.

- Phase 3 includes maintenance exercises and the gradual return to activities that do not require turning or twisting the ankle. This will be followed later by being able to do activities that require sharp, sudden turns (cutting activities)—such as tennis, basketball, or football.

This three-phase treatment program may take just 2 weeks to complete for minor sprains, or up to 6 to 12 weeks for more severe injuries.

Once you can stand on your ankle again, your doctor will prescribe exercise routines to strengthen your muscles and ligaments and increase your flexibility, balance and coordination. Later, you may walk, jog and run figure eights with your ankle taped or in a supportive ankle brace.

It’s important to complete the rehabilitation program because it makes it less likely that you’ll hurt the same ankle again. If you don’t complete rehabilitation, you could suffer chronic pain, instability and arthritis in your ankle. If your ankle still hurts, it could mean that the sprained ligament has not healed right, or that some other injury also happened.

To prevent future sprained ankles, pay attention to your body’s warning signs to slow down when you feel pain or fatigue, and stay in shape with good muscle balance, flexibility and strength in your soft tissues.

Sprained ankle exercises

Rehabilitation exercises are used to prevent stiffness, increase ankle strength, and prevent chronic ankle problems.

- Early motion. To prevent stiffness, your doctor or physical therapist will provide you with exercises that involve range-of-motion or controlled movements of your ankle without resistance.

- Strengthening exercises. Once you can bear weight without increased pain or swelling, exercises to strengthen the muscles and tendons in the front and back of your leg and foot will be added to your treatment plan. Water exercises may be used if land-based strengthening exercises, such as toe-raising, are too painful. Exercises with resistance are added as tolerated.

- Proprioception (balance) training. Poor balance often leads to repeat sprains and ankle instability. A good example of a balance exercise is standing on the affected foot with the opposite foot raised and eyes closed. Balance boards are often used in this stage of rehabilitation.

- Endurance and agility exercises. Once you are pain-free, other exercises may be added, such as agility drills. Running in progressively smaller figures-of-8 is excellent for agility and calf and ankle strength. The goal is to increase strength and range of motion as balance improves over time.

How to Stretch Your Ankle After A Sprain

You should perform the following stretches in stages once the initial pain and swelling have receded, usually within five to seven days. First is restoration of ankle range of motion, which should begin when you can tolerate weight bearing.

Once ankle range of motion has been almost or completely restored, you must strengthen your ankle. Along with strengthening, you should work toward a feeling of stability and comfort in your ankle, which orthopaedic foot and ankle specialists call proprioception.

Consider these home exercises when recuperating from an ankle sprain. Perform them twice per day.

- While seated, bring your ankle and foot all the way up as much as you can.

- Do this slowly, while feeling a stretch in your calf.

- Hold this for a count of 10.

- Repeat 10 times.

- From the seated starting position, bring your ankle down and in.

- Hold this inverted position for a count of 10.

- Repeat 10 times.

- Again from the starting position, bring your ankle up and out.

- Hold this everted position for a count of 10.

- Repeat 10 times.

- From the starting position, point your toes down and hold this position for a count of 10.

- Repeat 10 times.

This stretch should be done only when the pain in your ankle has significantly subsided.

- While standing on the edge of a stair, drop your ankles down and hold this stretched position for a count of 10.

- Repeat 10 times.

- Stand 12 inches from a wall with your toes pointing toward the wall.

- Squat down and hold this position for a count of 10.

- Repeat 10 times.

How to Strengthen Your Ankle After a Sprain

Following an ankle sprain, strengthening exercises should be performed once you can bear weight comfortably and your range of motion is near full. There are several types of strengthening exercises. The easiest to begin with are isometric exercises that you do by pushing against a fixed object with your ankle.

Once this has been mastered, you can progress to isotonic exercises, which involve using your ankle’s range of motion against some form of resistance. The photos below show isotonic exercises performed with a resistance band, which you can get from your local therapist or a sporting goods store.

Figure 2. Sprained ankle exercises

Range of Motion

- Ankle Alphabet: Spell out each letter of the alphabet with your foot, keeping your leg still while moving at the ankle. Use the biggest movements your ankle allows to go through the whole thing, A-Z.

- Calf Stretches: As soon as you can, start stretching your calves by putting the injured leg behind you, keeping your leg straight, and leaning pushing on a wall. If you can’t tolerate standing on your injured foot, straighten your leg by propping it up on a chair, or while sitting on your bed, then use a towel to pull the ball of your foot towards you. Hold for 30 seconds and repeat 3 times.

Strengthening

- Resisted 4-Way Ankle Holds: As pain allows, use a resistance band or towel to work against while you pull your ankle as far as you can in all 4 directions: up, down, inverted (top of foot towards the outside) and everted (sole of the foot towards the outside). Hold for 10 seconds, 5 times in each direction.

- Heel Raises: Once you can bear weight on your foot, stand on the ground and slowly raise your heels off as far as you can, hold for 5 seconds then slowly lower back down. Do 3 sets of 10 reps. You can progress this by standing half-way on a stair with both heels hanging off. Allow your heels to drop below the stair as you come down, holding that position for 5 seconds before rising back up (this can be a great way to stretch your calves too). Once you’re feeling really strong, switch to just using one foot at a time, rinse and repeat.

Balance

- Single Leg Stands: Stand on one foot (once you can tolerate it) while working up to balancing for 30 seconds. If needed, stand next to a chair or wall for support. Make it even tougher by closing your eyes, then progress to standing on a pillow to destabilize you. Stand with your affected leg on a pillow. Hold this position for a count of 10. Repeat 10 times.

- Advanced Balance Training: Once you’ve mastered single leg stands, you can really get your balance on by standing on one leg (yes, again) and putting both arms straight up above your head. Now slowly bend forward at the waist (keeping your back straight) as far as you can while keeping your balance. Not so easy, right? Try bending backwards as far as you can (hands still above your head), then to the left and to the right. Finally you can slowly twist to the left and right all while keeping balanced and tight in your core.

These same exercises that you’ve used to rehab your ankle can serve to strengthen it for future protection against another sprain. Progressing to longer periods of balancing and more reps on your resisted exercises will keep you strong and in tune with your ankle for years to come.

Once you have regained the motion and strength in your ankle, you are ready for sporting activities such as gentle jogging and biking. After you feel your ankle strength is approximately 80% of your other side, then you can begin cutting or twisting sports.

Using a brace or getting your ankle wrapped during risky activities will also help prevent future ankle sprains by adding increased support to your injured ligaments, even once they’ve healed. Whether the brace is soft or hard, find something comfortable and supportive that you’re willing to use each time you lace up your sport shoes.

Return to play

Athletes may return to sports following a talofibular ligament injury when they are able to run and pivot without pain while the ankle is braced. Bracing and taping of the injured ankle is continued during athletic activities for 6 months.

Surgery

Primary repair of acute lateral ligament tears is rarely indicated. Open repair seems to offer no advantage over closed management at the time of the initial injury. Delayed repair may be necessary in patients with chronic mechanical instability on clinical examination and functional instability; however, surgical intervention in these cases should only be considered after an aggressive rehabilitation program has been unsuccessful.

Maximum benefit from conservative therapy is reached after approximately 10 weeks of active rehabilitation. At this time, 20% of athletes continue to have symptoms secondary to either a functional or mechanical instability. If the patient has reached his or her maximal benefit from functional rehabilitation and has a persistent deficit, then surgical reconstruction should be considered 22.

Double lateral ligament tears

Staples 25 reported that young, active, athletic patients with tears of both the anterior talofibular ligament and the calcaneofibular ligament are best treated surgically. His cohorts included a group of young athletic patients with only 58% satisfactory results after immobilization and a subsequent, similar group of patients who had 88.9% satisfactory results with surgical repair 25. In the group of patients who underwent surgery, the average hospital stay was 7.6 days, and six (22.2%) of 27 patients had complications. Marginal necrosis of the skin at the wound edge and hypesthesia of the fourth and fifth toes and adjacent forepart of the foot were the only reported complications 25.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation after surgery involves time and attention to restore strength and range of motion so you can return to pre-injury function. The length of time you can expect to spend recovering depends upon the extent of injury and the amount of surgery that was done. Rehabilitation may take from weeks to months.

References- Kumai T, Takakura Y, Rufai A, Milz S, Benjamin M. The functional anatomy of the human anterior talofibular ligament in relation to ankle sprains. J Anat. 2002;200(5):457–465. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00050.x https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1570702

- Campbell SE, Warner M. MR imaging of ankle inversion injuries. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2008; 16:1–18

- Sarrafian SK, Kelikian AS. Sarrafian’s anatomy of the foot and ankle: descriptive, topographic, functional, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011:166–171

- Siegler S, Block J, Schneck CD. The mechanical characteristics of the collateral ligaments of the human ankle joint. Foot Ankle 1988; 8:234–242

- Boyce SH, Quigley MA, Campbell S. Management of ankle sprains: a randomised controlled trial of the treatment of inversion injuries using an elastic support bandage or an Aircast ankle brace. Br J Sports Med 2005; 39:91–96

- Baltopoulos P, Tzagarakis GP, Kaseta MA. Midterm results of a modified Evans repair for chronic lateral ankle instability. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; 422:180–185

- Geppert MJ. Soft-tissue injuries of the ankle. In: Mizel MS, Miller RA, Scioli MW, editors. Orthopaedic Knowledge Update, Foot and Ankle 2. Rosemont, Illinois: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1998. pp. 229–242.

- The frequency of injury, mechanism of injury, and epidemiology of ankle sprains. Garrick JG. Am J Sports Med. 1977 Nov-Dec; 5(6):241-2.

- Marder RA. Current methods for the evaluation of the ankle ligament injuries. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76A:1103–1111.

- SPRAINED ANKLES. I. ANATOMIC LESIONS IN RECENT SPRAINS. BROSTROEM L. Acta Chir Scand. 1964 Nov; 128():483-95.

- Linstrand A. Dissertation. Lund, Sweden: University of Lund; 1976. Lateral lesions in strained ankles. A clinical and roentogenological study with special reference to anterior instability of the talus. Studentlitteratur.

- Sprained ankles. VI. Surgical treatment of “chronic” ligament ruptures. Broström L. Acta Chir Scand. 1966 Nov; 132(5):551-65.

- Biomechanical characteristics of human ankle ligaments. Attarian DE, McCrackin HJ, DeVito DP, McElhaney JH, Garrett WE Jr. Foot Ankle. 1985 Oct; 6(2):54-8.

- Jayanthi N. Lower leg and ankle. McKeag DB, Moeller J, eds. ACSM’s Primary Care Sports Medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2007.

- Haraguchi N, Toga H, Shiba N, Kato F. Avulsion fracture of the lateral ankle ligament complex in severe inversion injury: incidence and clinical outcome. Am J Sports Med. 2007 Jul. 35(7):1144-52.

- Management and rehabilitation of ligamentous injuries to the ankle. Balduini, F.C., Vegso, J.J., Torg, J.S. et al. Sports Medicine (1987) 4: 364. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-198704050-00004

- Mark E. Easley, Sam W. Wiesel. Operative Techniques in Foot and Ankle Surgery. ISBN: 9781608319046

- Kumai T, Takakura Y, Rufai A et-al. The functional anatomy of the human anterior talofibular ligament in relation to ankle sprains. J. Anat. 2002;200 (5): 457-65.

- Brage ME, Colville MR, Early JS. Ankle and foot: trauma. Beaty JH, ed. Orthopaedic Knowledge Update 6. Rosemont, Ill: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1999. 597-612.

- van den Bekerom MP, Kerkhoffs GM, McCollum GA, Calder JD, van Dijk CN. Management of acute lateral ankle ligament injury in the athlete. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013 Jun. 21 (6):1390-5.

- Croy T, Saliba S, Saliba E, Anderson MW, Hertel J. Talofibular interval changes after acute ankle sprain: a stress ultrasonography study of ankle laxity. J Sport Rehabil. 2013 Nov. 22 (4):257-63.

- Kerkhoffs GM, Handoll HH, de Bie R, Rowe BH, Struijs PA. Surgical versus conservative treatment for acute injuries of the lateral ligament complex of the ankle in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Apr 18. CD000380

- Petersen W, Rembitzki IV, Koppenburg AG, Ellermann A, Liebau C, Brüggemann GP, et al. Treatment of acute ankle ligament injuries: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2013 Aug. 133 (8):1129-41.

- Evans GA, Hardcastle P, Frenyo AD. Acute rupture of the lateral ligament of the ankle. To suture or not to suture?. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984 Mar. 66 (2):209-12.

- Staples OS. Ruptures of the fibular collateral ligaments of the ankle. Result study of immediate surgical treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975 Jan. 57 (1):101-7.