What is an opportunistic infection

Opportunistic infections are infections that occur more often and are more severe in people with weakened immune systems than in people with healthy immune systems 1. People with weakened immune systems include people living with HIV or people receiving chemotherapy. People are at greatest risk for opportunistic infections when their CD4 count falls below 200, but you can get some opportunistic infections when your CD4 count is below 500.

Opportunistic infections are caused by a variety of germs (viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites). Opportunistic infection-causing germs can spread in the air; in saliva, semen, blood, urine, or feces (poop); or in contaminated food and water. Here are examples of common HIV-related opportunistic infections.

Here are examples of common HIV-related opportunistic infections:

- Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia

- Candidiasis (or thrush)—a fungal infection of the mouth, bronchi, trachea, lungs, esophagus, or vagina

- Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) infection—a viral infection that can cause lesions (sores) on the lips, mouth, and face

- Herpes zoster

- Mycobacterium avium complex infection

- Cytomegalovirus disease

- Cerebral toxoplasmosis

- Cryptococcosis

- Salmonella infection—a bacterial infection that affects the intestines (the gut)

- Toxoplasmosis—a parasitic infection that can affect the brain

Opportunistic infections are less common now than they were in the early days of HIV and AIDS because better treatments reduce the amount of HIV in a person’s body and keep a person’s immune system stronger. However, many people with HIV still develop opportunistic infections because they did not know they had HIV for many years after they were infected. Others people who know they have HIV can get opportunistic infections because they are not taking antiretroviral treatment (ART); they are on ART, but it is failing and the virus has weakened their immune system; or they have AIDS but are not taking medication to prevent opportunistic infections.

Despite the availability of multiple safe, effective, and simple antiretroviral treatment (ART) regimens, and a corresponding steady decline in the incidence of opportunistic infections 2, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that more than 40% of Americans with HIV are not effectively virally suppressed 3. As a result, opportunistic infections continue to cause preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States 4.

Achieving and maintaining durable viral suppression in all people with HIV, and thus preventing or substantially reducing the incidence of HIV related opportunistic infections, remains challenging for three main reasons:

- Not all HIV infections are diagnosed, and once diagnosed many persons have already experienced substantial immunosuppression. CDC estimates that in 2015, 15% of the people with HIV in the United States were unaware of their infections 5. Among those with diagnosed HIV, more than 50% had had HIV for more than 3 years20 and approximately 20% had a CD4 T lymphocyte (CD4) cell count <200 cells/mm3 (or <14%) at the time of diagnosis 6.

- Not all persons with diagnosed HIV receive timely continuous HIV care or are prescribed ART. CDC estimates that in 2015, 16% of persons with newly diagnosed HIV had not been linked to care within 3 months and among persons living with HIV only 57% were adequately engaged in continuous care 7

- Not all persons treated for HIV achieve durable viral suppression. CDC estimates that in 2014, only 49% of diagnosed patients were effectively linked to care and had durable viral suppression 8. Causes for the suboptimal response to treatment include poor adherence, unfavorable pharmacokinetics, or unexplained biologic factors 9.

Thus, some persons with HIV infection will continue to present with an opportunistic infection as the sentinel event leading to a diagnosis of HIV infection or present with an opportunistic infection as a complication of unsuccessful viral suppression.

Durable viral suppression eliminates most but not all opportunistic infections. Tuberculosis, pneumococcal disease, and dermatomal zoster are examples of infectious diseases that occur at higher incidence in persons with HIV regardless of CD4 count. The likelihood of each of these opportunistic infections occurring does vary inversely with the CD4 count 10.

When certain opportunistic infections occur— most notably tuberculosis and syphilis—they can increase plasma viral load 11, which both accelerates HIV progression and increases the risk of HIV transmission.

Staying in care and getting your lab tests done is one of the most important things you can do to prevent opportunistic infections. This will allow your provider to know when you might be at risk for opportunistic infections and work with you to prevent them. Some opportunistic infections can be prevented by taking additional medication that is used to prevent that opportunistic infection.

If you do develop an opportunistic infection, there are treatments available, such as antibiotics or antifungal drugs. Having an opportunistic infection may be a very serious medical situation and its treatment can be challenging. The best way to prevent opportunistic infections is to reduce your risk by staying in care, taking antiretroviral treatment (ART) every day, and keeping your viral load undetectable or very low so that your immune system can stay strong.

List of opportunistic infections

Following is a list of the most common opportunistic infections for people living in the United States 12.

| Candidiasis of bronchi, trachea, esophagus, or lungs | This illness is caused by infection with a common (and usually harmless) type of fungus called Candida. Candidiasis, or infection with Candida, can affect the skin, nails, and mucous membranes throughout the body. Persons with HIV infection often have trouble with Candida, especially in the mouth and vagina. However, candidiasis is only considered an OI when it infects the esophagus (swallowing tube) or lower respiratory tract, such as the trachea and bronchi (breathing tube), or deeper lung tissue. |

| Invasive cervical cancer | This is a cancer that starts within the cervix, which is the lower part of the uterus at the top of the vagina, and then spreads (becomes invasive) to other parts of the body. This cancer can be prevented by having your care provider perform regular examinations of the cervix |

| Coccidioidomycosis | This illness is caused by the fungus Coccidioides immitis. It most commonly acquired by inhaling fungal spores, which can lead to a pneumonia that is sometimes called desert fever, San Joaquin Valley fever, or valley fever. The disease is especially common in hot, dry regions of the southwestern United States, Central America, and South America. |

| Cryptococcosis | This illness is caused by infection with the fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. The fungus typically enters the body through the lungs and can cause pneumonia. It can also spread to the brain, causing swelling of the brain. It can infect any part of the body, but (after the brain and lungs) infections of skin, bones, or urinary tract are most common. |

| Cryptosporidiosis, chronic intestinal (greater than one month’s duration) | This diarrheal disease is caused by the protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium. Symptoms include abdominal cramps and severe, chronic, watery diarrhea. |

| Cytomegalovirus diseases (particularly retinitis) (CMV) | This virus can infect multiple parts of the body and cause pneumonia, gastroenteritis (especially abdominal pain caused by infection of the colon), encephalitis (infection) of the brain, and sight-threatening retinitis (infection of the retina at the back of eye). People with CMV retinitis have difficulty with vision that worsens over? time. CMV retinitis is a medical emergency because it can cause blindness if not treated promptly. |

| Encephalopathy, HIV-related | This brain disorder is a result of HIV infection. It can occur as part of acute HIV infection or can result from chronic HIV infection. Its exact cause is unknown but it is thought to be related to infection of the brain with HIV and the resulting inflammation. |

| Herpes simplex (HSV): chronic ulcer(s) (greater than one month’s duration); or bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis | Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a very common virus that for most people never causes any major problems. HSV is usually acquired sexually or from an infected mother during birth. In most people with healthy immune systems, HSV is usually latent (inactive). However, stress, trauma, other infections, or suppression of the immune system, (such as by HIV), can reactivate the latent virus and symptoms can return. HSV can cause painful cold sores (sometime called fever blisters) in or around the mouth, or painful ulcers on or around the genitals or anus. In people with severely damaged immune systems, HSV can also cause infection of the bronchus (breathing tube), pneumonia (infection of the lungs), and esophagitis (infection of the esophagus, or swallowing tube). |

| Histoplasmosis | This illness is caused by the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. Histoplasma most often infects the lungs and produces symptoms that are similar to those of influenza or pneumonia. People with severely damaged immune systems can get a very serious form of the disease called progressive disseminated histoplasmosis. This form of histoplasmosis can last a long time and involves organs other than the lungs. |

| Isosporiasis, chronic intestinal (greater than one month’s duration) | This infection is caused by the parasite Isospora belli, which can enter the body through contaminated food or water. Symptoms include diarrhea, fever, headache, abdominal pain, vomiting, and weight loss. |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) | This cancer, also known as KS, is caused by a virus called Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV) or human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8). KS causes small blood vessels, called capillaries, to grow abnormally. Because capillaries are located throughout the body, KS can occur anywhere. KS appears as firm pink or purple spots on the skin that can be raised or flat. KS can be life-threatening when it affects organs inside the body, such the lung, lymph nodes, or intestines. |

| Lymphoma, multiple forms | Lymphoma refers to cancer of the lymph nodes and other lymphoid tissues in the body. There are many different kinds of lymphomas. Some types, such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma, are associated with HIV infection. |

| Tuberculosis (TB) | Tuberculosis (TB) infection is caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis. TB can be spread through the air when a person with active TB coughs, sneezes, or speaks. Breathing in the bacteria can lead to infection in the lungs. Symptoms of TB in the lungs include cough, tiredness, weight loss, fever, and night sweats. Although the disease usually occurs in the lungs, it may also affect other parts of the body, most often the larynx, lymph nodes, brain, kidneys, or bones. |

| Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) or Mycobacterium kansasii, disseminated or extrapulmonary. Other Mycobacterium, disseminated or extrapulmonary. | MAC is caused by infection with different types of mycobacterium: Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, or Mycobacterium kansasii. These mycobacteria live in our environment, including in soil and dust particles. They rarely cause problems for persons with healthy immune systems. In people with severely damaged immune systems, infections with these bacteria spread throughout the body and can be life-threatening. |

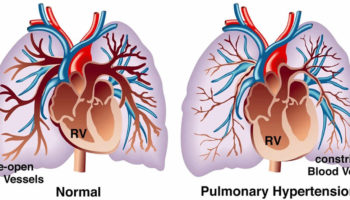

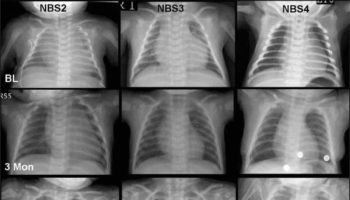

| Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) | This lung infection, also called PCP, is caused by a fungus, which used to be called Pneumocystis carinii, but now is named Pneumocystis jirovecii. PCP occurs in people with weakened immune systems, including people with HIV. The first signs of infection are difficulty breathing, high fever, and dry cough. |

| Pneumonia, recurrent | Pneumonia is an infection in one or both of the lungs. Many germs, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi can cause pneumonia, with symptoms such as a cough (with mucous), fever, chills, and trouble breathing. In people with immune systems severely damaged by HIV, one of the most common and life-threatening causes of pneumonia is infection with the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae, also called Pneumococcus. There are now effective vaccines that can prevent infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae and all persons with HIV infection should be vaccinated. |

| Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy | This rare brain and spinal cord disease is caused by the JC (John Cunningham) virus. It is seen almost exclusively in persons whose immune systems have been severely damaged by HIV. Symptoms may include loss of muscle control, paralysis, blindness, speech problems, and an altered mental state. This disease often progresses rapidly and may be fatal. |

| Salmonella septicemia, recurrent | Salmonella are a kind of bacteria that typically enter the body through ingestion of contaminated food or water. Infection with salmonella (called salmonellosis) can affect anyone and usually causes a self-limited illness with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Salmonella septicemia is a severe form of infection in which the bacteria circulate through the whole body and exceeds the immune system’s ability to control it. |

| Toxoplasmosis of brain | This infection, often called toxo, is caused by the parasite Toxoplasma gondii. The parasite is carried by warm-blooded animals including cats, rodents, and birds and is excreted by these animals in their feces. Humans can become infected with it by inhaling dust or eating food contaminated with the parasite. Toxoplasma can also occur in commercial meats, especially red meats and pork, but rarely poultry. Infection with toxo can occur in the lungs, retina of the eye, heart, pancreas, liver, colon, testes, and brain. Although cats can transmit toxoplasmosis, litter boxes can be changed safely by wearing gloves and washing hands thoroughly with soap and water afterwards. All raw red meats that have not been frozen for at least 24 hours should be cooked through to an internal temperature of at least 150oF. |

| Wasting syndrome due to HIV | Wasting is defined as the involuntary loss of more than 10% of one’s body weight while having experienced diarrhea or weakness and fever for more than 30 days. Wasting refers to the loss of muscle mass, although part of the weight loss may also be due to loss of fat. |

Why do people with HIV get opportunistic infections?

Once a person is infected with HIV, the virus begins to multiply and to damage the immune system. A weakened immune system makes it harder for the body to fight off HIV-related opportunistic infections.

HIV medicines prevent HIV from damaging the immune system. But if a person with HIV does not take HIV medicines, HIV infection can gradually destroy the immune system and advance to AIDS. Many opportunistic infections, for example, certain forms of pneumonia and tuberculosis (TB), are considered AIDS-defining conditions. AIDS-defining conditions are infections and cancers that are life-threatening in people with HIV.

Are opportunistic infections common in people with HIV?

Before HIV medicines were available to treat HIV infection, opportunistic infections were the main cause of illness and death in people with HIV. HIV medicines are now widely used in the United States so fewer people with HIV get opportunistic infections. By preventing HIV from damaging the immune system, HIV medicines reduce the risk of opportunistic infections.

However, opportunistic infections are still a problem for many people with HIV. Some people with HIV get opportunistic infections for the following reasons:

- About 15% of people who have HIV don’t know that they are infected. An opportunistic infection may be the first sign that they have HIV.

- Some people who know they have HIV aren’t getting treatment with HIV medicines. Without HIV treatment, they are more likely to get an opportunistic infection.

- Some people may be taking HIV medicines, but the medicines aren’t controlling their HIV. Poorly controlled HIV can be due to many factors, including lack of health care, poor medication adherence, or incomplete absorption of HIV medicines. People with poorly controlled HIV have an increased risk of getting an opportunistic infection.

What can people with HIV do to prevent getting an opportunistic infection?

For people with HIV, the best protection against opportunistic infections is to take HIV medicines every day.

People living with HIV can also take the following steps to reduce their risk of getting an opportunistic infection.

Avoid contact with the germs that can cause opportunistic infections.

The germs that can cause opportunistic infections can spread in the feces of people and animals. To prevent opportunistic infections, don’t touch animal feces. Wash your hands with warm, soapy water after touching anything soiled with human feces, for example, a dirty diaper. Ask your health care provider about other ways to avoid the germs that can cause opportunistic infections.

In addition to taking HIV medications to keep your immune system strong, there are other steps you can take to prevent getting an opportunistic infection:

- Prevent exposure to other sexually transmitted infections.

- Don’t share drug injection equipment. Blood with hepatitis C in it can remain in syringes and needles after use and the infection can be transmitted to the next user.

- Get vaccinated – your doctor can tell you what vaccines you need. If he or she doesn’t, you should ask.

- Understand what germs you are exposed to (such as tuberculosis or germs found in the stools, saliva, or on the skin of animals) and limit your exposure to them.

- Don’t consume certain foods, including undercooked eggs, unpasteurized (raw) milk and cheeses, unpasteurized fruit juices, or raw seed sprouts.

- Don’t drink untreated water such as water directly from lakes or rivers. Tap water in foreign countries is also often not safe. Use bottled water or water filters.

- Ask your doctor to review with you the other things you do at work, at home, and on vacation to make sure you aren’t exposed to an opportunistic infection.

Be careful about what you eat and drink.

Food and water can be contaminated with opportunistic infection-causing germs. To be safe, don’t eat or drink the following foods:

- Raw or undercooked eggs, for example, in homemade mayonnaise or uncooked cookie dough

- Raw or undercooked poultry, meat, and seafood (especially raw shellfish)

- Unpasteurized milk, cheeses, and fruit juices

- Raw seed sprouts, such as alfalfa sprouts or mung bean sprouts

Only drink tap water, filtered water, or bottled water. Don’t drink water directly from a lake or river.

Can opportunistic infections be treated?

There are many medicines to treat HIV-related opportunistic infections, including antiviral, antibiotic, and antifungal drugs. The type of medicine used depends on the opportunistic infection.

Once an opportunistic infection is successfully treated, a person may continue to use the same medicine or an additional medicine to prevent the opportunistic infection from reoccurring (coming back).

HIV opportunistic infections guidelines

Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. You can get a copy of the latest guidelines from https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines

Table 1. Prophylaxis to Prevent First Episode of Opportunistic Disease

| Opportunistic Infections | Indication | Preferred | Alternative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) |

Note: Patients who are receiving pyrimethamine/ sulfadiazine for treatment or suppression of toxoplasmosis do not require additional PCP prophylaxis (AII). |

|

|

| Toxoplasma gondii encephalitis |

Note: All regimens recommended for primary prophylaxis against toxoplasmosis are also effective as PCP prophylaxis | TMP-SMXa 1 DS PO daily (AII) |

|

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection (TB) (i.e., treatment of latent TB infection [LTBI]) |

|

|

Rifapentine only recommended for patients receiving raltegravir or efavirenz-based ART regimen For persons exposed to drug-resistant TB, select anti-TB drugs after consultation with experts or public health authorities (AII). |

| Disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) disease | CD4 count <50 cells/µL—after ruling out active disseminated MAC disease based on clinical assessment (AI). |

| Rifabutin (dose adjusted based on concomitant ART)e (BI); rule out active TB before starting rifabutin. |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae infection | For individuals who have not received any pneumococcal vaccine, regardless of CD4 count, followed by:

| PCV13 0.5 mL IM x 1 (AI). PPV23 0.5 mL IM at least 8 weeks after the PCV13 vaccine (AII). PPV23 can be offered at least 8 weeks after receiving PCV13 (CIII) or can wait until CD4 count increased to ≥200 cells/µL (BIII). | PPV23 0.5 mL IM x 1 (BII) |

| For individuals who have previously received PPV23 | One dose of PCV13 should be given at least 1 year after the last receipt of PPV23 (AII). | ||

Re-vaccination

|

| ||

| Influenza A and B virus infection | All HIV-infected patients (AIII) | Inactivated influenza vaccine annually (per recommendation for the season) (AIII) Live-attenuated influenza vaccine is contraindicated in HIV-infected patients (AIII). | |

| Syphilis |

| Benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM for 1 dose (AII) | For penicillin-allergic patients:

|

| Histoplasma capsulatum infection | CD4 count ≤150 cells/µL and at high risk because of occupational exposure or live in a community with a hyperendemic rate of histoplasmosis (>10 cases/100 patient-years) (BI) | Itraconazole 200 mg PO daily (BI) | |

| Coccidioido-mycosis | A new positive IgM or IgG serologic test in patients who live in a disease-endemic area and with CD4 count <250 cells/µL (BIII) | Fluconazole 400 mg PO daily (BIII) | |

| Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection | Pre-exposure prevention: Patients with CD4 counts ≥200 cells/µL who have not been vaccinated, have no history of varicella or herpes zoster, or who are seronegative for VZV (CIII) Note: Routine VZV serologic testing in HIV-infected adults and adolescents is not recommended. Post-exposure prevention: (AIII) | Pre-exposure prevention: Primary varicella vaccination (Varivax™), 2 doses (0.5 mL SQ each) administered 3 months apart (CIII). If vaccination results in disease because of vaccine virus, treatment with acyclovir is recommended (AIII). Post-exposure prevention: Note: VariZIG is exclusively distributed by FFF Enterprises at 800-843-7477. Individuals receiving monthly high-dose IVIG (>400 mg/kg) are likely to be protected if the last dose of IVIG was administered <3 weeks before exposure. | Pre-exposure prevention: VZV-susceptible household contacts of susceptible HIV-infected persons should be vaccinated to prevent potential transmission of VZV to their HIV-infected contacts (BIII). Alternative post-exposure prevention:

These alternatives have not been studied in the HIV population. If antiviral therapy is used, varicella vaccines should not be given until at least 72 hours after the last dose of the antiviral drug. |

| Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection | Females and males aged 13–26 years (BIII) |

| For patients who have completed a vaccination series with the recombinant bivalent or quadrivalent vaccine, providers may consider additional vaccination with recombinant 9-valent vaccine, but there are no data to define who might benefit or how cost effective this approach might be (CIII). |

| Hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection | HAV-susceptible patients with chronic liver disease, or who are injection-drug users, or MSM (AII). | Hepatitis A vaccine 1 mL IM x 2 doses at 0 and 6–12 months (AII). IgG antibody response should be assessed 1 month after vaccination; non-responders should be revaccinated when CD4 count >200 cells/µL (BIII). | For patients susceptible to both HAV and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (see below): Combined HAV and HBV vaccine (Twinrix®), 1 mL IM as a 3-dose (0, 1, and 6 months) or 4-dose series (days 0, 7, 21 to 30, and 12 months) (AII) |

| Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection |

|

Anti-HBs should be obtained 1-2 months after completion of the vaccine series. Patients with anti-HBs <10 IU/mL are considered non-responders, and should be revaccinated with another 3-dose series (BIII). | Some experts recommend vaccinating with 4-doses of double dose of either HBV vaccine (BI). |

Vaccine Non-Responders:

| Re-vaccinate with a second vaccine series (BIII) |

| |

| Malaria | Travel to disease-endemic area | Recommendations are the same for HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected patients. Recommendations are based on region of travel, malaria risks, and drug susceptibility in the region. Refer to the following website for the most recent recommendations based on region and drug susceptibility: http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/. | |

| Penicilliosis | Patients with CD4 cell counts <100 cells/µL who live or stay for a long period in rural areas in northern Thailand, Vietnam, or Southern China (BI) | Itraconazole 200 mg once daily (BI) | Fluconazole 400 mg PO once weekly (BII) |

| Key to Acronyms: anti-HBc = hepatitis B core antibody; anti-HBs = hepatitis B surface antibody; ART = antiretroviral therapy; BID = twice daily; BIW = twice a week; CD4 = CD4 T lymphocyte cell; DOT = directly observed therapy; DS = double strength; HAV = hepatitis A virus; HBV = hepatitis B virus; HPV = human papillomavirus; IgG = immunoglobulin G; IgM = immunoglobulin M; IM = intramuscular; INH = isoniazid; IV= intravenously; IVIG = intravenous immunoglobulin; LTBI = latent tuberculosis infection; MAC = Mycobacterium avium complex; PCP = Pneumocystis pneumonia; PCV13 = 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PO = orally; PPV23 = 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharides vaccine; SQ = subcutaneous; SS = single strength; TB = tuberculosis; TMP-SMX = Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; VZV = varicella zoster virus a TMP-SMX DS once daily also confers protection against toxoplasmosis and many respiratory bacterial infections; lower dose also likely confers protection | |||

Footnotes:

Evidence Rating

Strength of Recommendation:

- A: Strong recommendation for the statement

- B: Moderate recommendation for the statement

- C: Optional recommendation for the statement

Quality of Evidence for the Recommendation:

- I: One or more randomized trials with clinical outcomes and/or validated laboratory endpoints

- II: One or more well-designed, nonrandomized trials or observational cohort studies with long-term clinical outcomes

- III: Expert opinion

In cases where there are no data for the prevention or treatment of an opportunistic infection based on studies conducted in HIV-infected populations, but data derived from HIV-uninfected patients exist that can plausibly guide management decisions for patients with HIV/AIDS, the data will be rated as III but will be assigned recommendations of A, B, C depending on the strength of recommendation.

[Source 13]Table 2. Treatment of AIDS-Associated Opportunistic Infections (Includes Recommendations for Acute Treatment and Secondary Prophylaxis/Chronic Suppressive/Maintenance Therapy)

| Opportunistic Infection | Preferred Therapy | Alternative Therapy | Other Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumocystis Pneumonia (PCP) | Patients who develop PCP despite TMP-SMX prophylaxis can usually be treated with standard doses of TMP-SMX (BIII). Duration of PCP treatment: 21 days (AII) For Moderate-to-Severe PCP:

For Mild-to-Moderate PCP:

Secondary Prophylaxis, after completion of PCP treatment:

| For Moderate-to-Severe PCP:

For Mild-to-Moderate PCP:

Secondary Prophylaxis, after completion of PCP treatment:

| Indications for Adjunctive Corticosteroids (AI):

Prednisone Doses (Beginning as Early as Possible and Within 72 Hours of PCP Therapy) (AI):

IV methylprednisolone can be administered as 75% of prednisone dose. Benefit of corticosteroid if started after 72 hours of treatment is unknown, but some clinicians will use it for moderate-to-severe PCP (BIII). Whenever possible, patients should be tested for G6PD before use of dapsone or primaquine. Alternative therapy should be used in patients found to have G6PD deficiency. Patients who are receiving pyrimethaminea/sulfadiazine for treatment or suppression of toxoplasmosis do not require additional PCP prophylaxis (AII). If TMP-SMX is discontinued because of a mild adverse reaction, re-institution should be considered after the reaction resolves (AII). The dose can be increased gradually (desensitization) (BI), reduced, or the frequency modified (CIII). TMP-SMX should be permanently discontinued in patients with possible or definite Stevens-Johnson Syndrome or toxic epidermal necrosis (AII). |

| Toxoplasma gondii Encephalitis | Treatment of Acute Infection (AI):

Duration for Acute Therapy:

Chronic Maintenance Therapy:

| Treatment of Acute Infection:

Chronic Maintenance Therapy:

*Pyrimethaminea and leucovorin doses are the same as for preferred therapy. | Refer to http://www.daraprimdirect.com for information regarding how to access pyrimethamine If pyrimethamine is unavailable or there is a delay in obtaining it, TMP-SMX should be utilized in place of pyrimethamine-sulfadiazine (BI). For patients with a history of sulfa allergy, sulfa desensitization should be attempted using one of several published strategies (BI). Atovaquone should be administered until therapeutic doses of TMP-SMX are achieved (CIII). Adjunctive corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone) should only be administered when clinically indicated to treat mass effect associated with focal lesions or associated edema (BIII); discontinue as soon as clinically feasible. Anticonvulsants should be administered to patients with a history of seizures (AIII) and continued through acute treatment, but should not be used as seizure prophylaxis (AIII). If clindamycin is used in place of sulfadiazine, additional therapy must be added to prevent PCP (AII). |

| Cryptosporidiosis |

| No therapy has been shown to be effective without ART. Trial of these agents may be used in conjunction with, but not instead of, ART:

| Tincture of opium may be more effective than loperamide in management of diarrhea (CIII). |

| Microsporidiosis | For GI Infections Caused by Enterocytozoon bienuesi:

For Intestinal and Disseminated (Not Ocular) Infections Caused by Microsporidia Other Than E. bienuesi and Vittaforma corneae:

For Ocular Infection:

| For GI Infections Caused by E. bienuesi:

For Disseminated Disease Attributed to Trachipleistophora or Anncaliia:

| Anti-motility agents can be used for diarrhea control if required (BIII). |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) Disease | After collecting specimen for culture and molecular diagnostic tests, empiric TB treatment should be started in individuals with clinical and radiographic presentation suggestive of TB (AIII). Refer to Table 3 for dosing recommendations. Initial Phase (2 Months, Given Daily, 5–7 Times/Week by DOT) (AI):

Continuation Phase:

Total Duration of Therapy (For Drug-Susceptible TB):

Total duration of therapy should be based on number of doses received, not on calendar time | Treatment for Drug Resistant TB Resistant to INH:

Resistant to Rifamycins +/- Other Drugs:

| Adjunctive corticosteroid improves survival for TB meningitis and pericarditis (AI). See text for drug, dose, and duration recommendations. All rifamycins may have significant pharmacokinetic interactions with antiretroviral drugs, please refer to the Drug Interactions section in the Adult and Adolescent ARV Guidelines) for dosing recommendations Therapeutic drug monitoring should be considered in patients receiving rifamycin and interacting ART. Paradoxical IRIS that is not severe can be treated with NSAIDs without a change in TB or HIV therapy (BIII). For severe IRIS reaction, consider prednisone and taper over 4 weeks based on clinical symptoms (BIII). For example:

A more gradual tapering schedule over a few months may be necessary for some patients. |

| Disseminated Myco-bacterium avium Complex (MAC) Disease | At Least 2 Drugs as Initial Therapy With:

Duration:

| Addition of a third or fourth drug should be considered for patients with advanced immunosuppression (CD4 counts <50 cells/ µL), high mycobacterial loads (>2 log CFU/mL of blood), or in the absence of effective ART (CIII). Third or Fourth Drug Options May Include:

| Testing of susceptibility to clarithromycin and azithromycin is recommended (BIII). NSAIDs can be used for patients who experience moderate to severe symptoms attributed to IRIS (CIII). If IRIS symptoms persist, short-term (4–8 weeks) systemic corticosteroids (equivalent to 20–40 mg prednisone) can be used (CII). |

| Bacterial Respiratory Diseases (with focus on pneumonia) | Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated promptly for patients presenting with clinical and radiographic evidence consistent with bacterial pneumonia. The recommendations listed are suggested empiric therapy. The regimen should be modified as needed once microbiologic results are available (BIII). | Fluoroquinolones should be used with caution in patients in whom TB is suspected but is not being treated. Empiric therapy with a macrolide alone is not routinely recommended, because of increasing pneumococcal resistance (BIII). Patients receiving a macrolide for MAC prophylaxis should not receive macrolide monotherapy for empiric treatment of bacterial pneumonia. For patients begun on IV antibiotic therapy, switching to PO should be considered when they are clinically improved and able to tolerate oral medications. Chemoprophylaxis can be considered for patients with frequent recurrences of serious bacterial pneumonia (CIII). Clinicians should be cautious about using antibiotics to prevent recurrences because of the potential for developing drug resistance and drug toxicities. | |

Empiric Outpatient Therapy:

Duration: 7–10 days (a minimum of 5 days). Patients should be afebrile for 48–72 hours and clinically stable before stopping antibiotics. Empiric Therapy for Non-ICU Hospitalized Patients:

Empiric Therapy for ICU Patients:

Empiric Therapy for Patients at Risk of Pseudomonas Pneumonia:

Empiric Therapy for Patients at Risk for Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Pneumonia:

| Empiric Outpatient Therapy:

Empiric Therapy for Non-ICU Hospitalized Patients:

Empiric Therapy For ICU Patients:

Empiric Therapy for Patients at Risk of Pseudomonas Pneumonia:

| ||

| Bacterial Enteric Infections: Empiric Therapy pending definitive diagnosis. | Diagnostic fecal specimens should be obtained before initiation of empiric antibiotic therapy. If culture is positive, antibiotic susceptibilities should be performed to inform antibiotic choices given increased reports of antibiotic resistance. If a culture independent diagnostic test is positive, reflex cultures for antibiotic susceptibilities should also be done. Empiric antibiotic therapy is indicated for advanced HIV patients (CD4 count <200 cells/µL or concomitant AIDS-defining illnesses), with clinically severe diarrhea (≥6 stools/day or bloody stool) and/or accompanying fever or chills. Empiric Therapy:

Therapy should be adjusted based on the results of diagnostic work-up. For patients with chronic diarrhea (>14 days) without severe clinical signs, empiric antibiotics therapy is not necessary, can withhold treatment until a diagnosis is made. | Empiric Therapy:

| Oral or IV rehydration (if indicated) should be given to patients with diarrhea (AIII). Antimotility agents should be avoided if there is concern about inflammatory diarrhea, including Clostridium-difficile-associated diarrhea (BIII). If no clinical response after 3-4 days, consider follow-up stool culture with antibiotic susceptibility testing or alternative diagnostic tests (e.g., toxin assays, molecular testing) to evaluate alternative diagnosis, antibiotic resistance, or drug-drug interactions. IV antibiotics and hospitalization should be considered in patients with marked nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, electrolyte abnormalities, acidosis, and blood pressure instability. |

| Salmonellosis | All HIV-infected patients with salmonellosis should receive antimicrobial treatment due to an increase of bacteremia (by 20-100 fold) and mortality (by up to 7-fold) compared to HIV negative individuals. (AIII) | Oral or IV rehydration if indicated (AIII). Antimotility agents should be avoided (BIII). The role of long-term secondary prophylaxis in patients with recurrent Salmonella bacteremia is not well established. Must weigh benefit against risks of long-term antibiotic exposure (BIII). Effective ART may reduce the frequency, severity, and recurrence of salmonella infections. | |

Duration of Therapy:

For gastroenteritis with bacteremia:

Secondary Prophylaxis Should Be Considered For:

|

| ||

| Shigellosis |

Duration of Therapy:

Note |

Note – Azithromycin resistant Shigella spp has been reported in HIV-infected MSM | Therapy is indicated both to shorten duration of illness and prevent spread of infection (AIII). Given increasing antimicrobial resistance and limited data showing that antibiotic therapy limits transmission, antibiotic treatment may be withheld in patients with CD4 >500 cells/mm3 whose diarrhea resolves prior to culture confirmation of Shigella infection (CIII). Oral or IV rehydration if indicated (AIII). Antimotility agents should be avoided (BIII). If no clinical response after 5–7 days, consider follow-up stool culture, alternative diagnosis, or antibiotic resistance. Effective ART may decrease the risk of recurrence of Shigella infections. |

| Campylobacteriosis | For Mild Disease and If CD4 Count >200 cells/μL:

For Mild-to-Moderate Disease (If Susceptible):

For Campylobacter Bacteremia:

Duration of Therapy:

| For Mild-to-Moderate Disease (If Susceptible)

Add an aminoglycoside to fluoroquinolone in bacteremic patients (BIII). | Oral or IV rehydration if indicated (AIII). Antimotility agents should be avoided (BIII). If no clinical response after 5–7 days, consider follow-up stool culture, alternative diagnosis, or antibiotic resistance. There is an increasing rate of fluoroquinolone resistance in the United States (24% resistance in 2011). The rational of addition of an aminoglycoside to a fluoroquinolone in bacteremic patients is to prevent emergence of quinolone resistance. Effective ART may reduce the frequency, severity, and recurrence of campylobacter infections. |

| Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) | Vancomycin 125 mg (PO) QID for 10-14 days (AI) For severe, life-threatening CDI, see text and references for additional information. | For mild, outpatient disease: metronidazole 500 mg (PO) TID for 10–14 days (CII) | Recurrent CDI: Treatment is the same as in patients without HIV infection. Fecal microbiota therapy may be successful and safe to treat recurrent CDI in HIV-infected patients (CIII). See text and references for additional information. |

| Bartonellosis | For Bacillary Angiomatosis, Peliosis Hepatis, Bacteremia, and Osteomyelitis:

CNS Infections:

Confirmed Bartonella Endocarditis:

Other Severe Infections:

Duration of Therapy:

| For Bacillary Angiomatosis, Peliosis Hepatis, Bacteremia, And Osteomyelitis:

Confirmed Bartonella Endocarditis but with Renal Insufficiency:

| When RIF is used, take into consideration the potential for significant interaction with ARV drugs and other medications (see Table 5 for dosing recommendations). If relapse occurs after initial (>3 month) course of therapy, long-term suppression with doxycycline or a macrolide is recommended as long as CD4 count <200 cells/µL (AIII). |

| Syphilis (Treponema pallidum Infection) | Early Stage (Primary, Secondary, and Early-Latent Syphilis):

Late-Latent Disease (>1 year or of Unknown Duration, and No Signs of Neurosyphilis):

Late-Stage (Tertiary–Cardiovascular or Gummatous Disease):

Neurosyphilis (Including Otic or Ocular Disease):

| Early Stage (Primary, Secondary, and Early-Latent Syphilis): For penicillin-allergic patients

Late-Latent Disease (>1 year or of Unknown Duration, and No Signs of Neurosyphilis):

Neurosyphilis:

| The efficacy of non-penicillin alternatives has not been evaluated in HIV-infected patients and they should be used only with close clinical and serologic monitoring. Combination of procaine penicillin and pro-benecid is not recommended for patients who are allergic to sulfa-containing medications (AIII). The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is an acute febrile reaction accompanied by headache and myalgia that can occur within the first 24 hours after therapy for syphilis. This reaction occurs most frequently in patients with early syphilis, high non-treponemal titers, and prior penicillin treatment. |

| Mucocutaneous candidiasis | For Oropharyngeal Candidiasis; Initial Episodes (For 7–14 Days): Oral Therapy

For Esophageal Candidiasis (For 14–21 Days):

For Uncomplicated Vulvo-Vaginal Candidiasis:

For Severe or Recurrent Vulvo-Vaginal Candidiasis:

| For Oropharyngeal Candidiasis; Initial Episodes (For 7–14 Days): Oral Therapy

Topical Therapy

For Esophageal Candidiasis (For 14–21 Days):

For Uncomplicated Vulvo-Vaginal Candidiasis:

| Chronic or prolonged use of azoles may promote development of resistance. Higher relapse rate for esophageal candidiasis seen with echin-ocandins than with fluconazole use. Suppressive therapy usually not recommended (BIII) unless patients have frequent or severe recurrences. If Decision Is to Use Suppressive Therapy:

Esophageal candidiasis:

Vulvo-vaginal candidiasis:

|

| Cryptococcosis | Cryptococcal Meningitis Induction Therapy (for at least 2 weeks, followed by consolidation therapy):

Consolidation Therapy (for at least 8 weeks (AI), followed by maintenance therapy):

Maintenance Therapy:

For Non-CNS, Extrapulmonary Cryptococcosis and Diffuse Pul-monary Disease:

Non-CNS Cryptococcosis with Mild-to-Moderate Symptoms and Focal Pulmonary Infiltrates:

| Cryptococcal meningitis Induction Therapy (for at least 2 weeks, followed by consolidation therapy):

Consolidation Therapy (for at least 8 weeks (AI), followed by maintenance therapy):

Maintenance Therapy:

| Addition of flucytosine to amphotericin B has been associated with more rapid sterilization of CSF and decreased risk for subsequent relapse. Patients receiving flucytosine should have either blood levels monitored (peak level 2 hours after dose should be 30–80 mcg/mL) or close monitoring of blood counts for development of cytopenia. Dosage should be adjusted in patients with renal insufficiency (BII). Opening pressure should always be measured when an LP is performed (AII). Repeated LPs or CSF shunting are essential to effectively manage increased intracranial pressure (BIII). Corticosteroids and mannitol are ineffective in reducing ICP and are NOT recommended (BII). Corticosteroid should not be routinely used during induction therapy unless it is for the management of IRIS (AI). |

| Histoplasmosis | Moderately Severe to Severe Disseminated Disease Induction Therapy (for at least 2 weeks or until clinically improved):

Maintenance Therapy

Less Severe Disseminated Disease

Duration of Therapy:

Meningitis

Maintenance Therapy:

Long-Term Suppression Therapy:

| Moderately Severe to Severe Disseminated Disease Induction Therapy (for at least 2 weeks or until clinically improved):

Alternatives to Itraconazole for Maintenance Therapy or Treatment of Less Severe Disease:

Meningitis:

Long-Term Suppression Therapy:

| Itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole may have significant interactions with certain ARV agents. These interactions are complex and can be bi-directional. Refer to Table 5 for dosage recommendations. Therapeutic drug monitoring and dosage adjustment may be necessary to ensure triazole antifungal and ARV efficacy and reduce concentration-related toxicities. Random serum concentration of itraconazole + hydroitraconazole should be >1 μg/mL. Clinical experience with voriconazole or posaconazole in the treatment of histoplasmosis is limited. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis in HIV-infected patients with CD4 counts >300 cells/µL should be managed as non-immunocompromised host (AIII). |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Clinically Mild Infections (e.g., Focal Pneumonia):

Bone or Joint Infections:

Severe, Non-Meningeal Infection (Diffuse Pulmonary Infection or Severely Ill Patients with Extrathoracic, Disseminated Disease):

Meningeal Infections:

| Mild Infections (Focal Pneumonia) For Patients Who Failed to Respond to Fluconazole or Itraconazole:

Bone or Joint Infection:

Severe, Non-Meningeal Infection (Diffuse Pulmonary Infection or Severely Ill Patients with Extrathoracic, Disseminated Disease):

Meningeal Infections:

| Relapse can occur in 25%–33% of HIV-negative patients with diffuse pulmonary or disseminated diseases . Therapy should be given for at least 12 months and usually much longer; discontinuation is dependent on clinical and serological response and should be made in consultation with experts (BIII). Therapy should be lifelong in patients with meningeal infections because relapse occurs in 80% of HIV-infected patients after discontinuation of triazole therapy (AII). * Fluconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole may have significant interactions with other medications including ARV drugs. These interactions are complex and can be bi- directional. Refer to Table 5 or Antiretroviral guidelines for dosage recommendations. Therapeutic drug monitoring and dosage adjustment may be necessary to ensure triazole antifungal and antiretroviral efficacy and reduce concentration-related toxicities. Intrathecal amphotericin B should only be given in consultation with a specialist and administered by an individual with experience with the technique. |

| Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Disease | CMV Retinitis Induction Therapy (followed by Chronic Maintenance Therapy) For Immediate Sight-Threatening Lesions (within 1500 microns of the fovea):

For Peripheral Lesions

Chronic Maintenance

CMV Esophagitis or Colitis:

Well-Documented, Histologically Confirmed CMV Pneumonia:

CMV Neurological Disease

| CMV Retinitis For Immediate Sight-Threatening Lesions (within 1500 microns of the fovea): Intravitreal therapy as listed in the Preferred section, plus one of the following: Alternative Systemic Induction Therapy (followed by Chronic Maintenance Therapy)

Chronic Maintenance (for 3-6 months until ART induced immune recovery) (see Table 4):

CMV Esophagitis or Colitis:

| The choice of therapy for CMV retinitis should be individualized, based on location and severity of the lesions, level of immunosuppression, and other factors (e.g., concomitant medications and ability to adhere to treatment) (AIII). Given the evident benefits of systemic therapy in preventing contralateral eye involvement, reduce CMV visceral disease and improve survival, whenever feasible, treatment should include systemic therapy The ganciclovir ocular implant, which is effective for treatment of CMV retinitis is no longer available. For sight threatening retinitis, intra-vitreal injections of ganciclovir or foscarnet can be given to achieve higher ocular concentration faster. Routine (i.e., every 3 months) ophthalmologic follow-up is recommended after stopping chronic maintenance therapy for early detection of relapse or IRU, and then periodically after sustained immune reconstitution (AIII). IRU may develop in the setting of immune reconstitution. Treatment of IRU

Initial therapy in patients with CMV retinitis, esophagitis, colitis, and pneumonitis should include initiation or optimization of ART (BIII). |

| Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) Disease | Orolabial Lesions (For 5–10 Days):

Initial or Recurrent Genital HSV (For 5–14 Days):

Severe Mucocutaneous HSV:

Chronic Suppressive Therapy

| For Acyclovir-Resistant HSV Preferred Therapy:

Alternative Therapy (CIII):

Duration of Therapy:

| Patients with HSV infections can be treated with episodic therapy when symptomatic lesions occur, or with daily suppressive therapy to prevent recurrences. Topical formulations of trifluridine and cidofovir are not commercially available. Extemporaneous compounding of topical products can be prepared using trifluridine ophthalmic solution and the IV formulation of cidofovir. |

| Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) Disease | Primary Varicella Infection (Chickenpox) Uncomplicated Cases (For 5–7 Days):

Severe or Complicated Cases:

Herpes Zoster (Shingles)

Extensive Cutaneous Lesion or Visceral Involvement:

Progressive Outer Retinal Necrosis (PORN):

Acute Retinal Necrosis (ARN):

| Primary Varicella Infection (Chickenpox) Uncomplicated Cases (For 5-7 Days):

Herpes Zoster (Shingles)

| In managing VZV retinitis – Consultation with an ophthalmologist experienced in management of VZV retinitis is strongly recommended (AIII). Duration of therapy for VZV retinitis is not well defined, and should be determined based on clinical, virologic, and immunologic responses and ophthalmologic responses. Optimization of ART is recommended for serious and difficult-to-treat VZV infections (e.g., retinitis, encephalitis) (AIII). |

| HHV-8 Diseases (Kaposi Sarcoma [KS], Primary Effusion Lymphoma [PEL], Multicentric Castleman’s Disease [MCD]) | Mild To Moderate KS (localized involvement of skin and/or lymph nodes):

Advanced KS [visceral (AI) or disseminated cutaneous KS (BIII)]:

Primary Effusion Lymphoma:

MCD Therapy Options (in consultation with specialist, depending on HIV/HHV-8 status, presence of organ failure, and refractory nature of disease): ART (AIII) along with one of the following

Concurrent KS and MCD

| MCD

|

|

| Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Disease | Treatment of Condyloma Acuminata (Genital Warts) | HIV-infected patients may have larger or more numerous warts and may not respond as well to therapy for genital warts when compared to HIV-uninfected individuals. Topical cidofovir has activity against genital warts, but the product is not commercially available (CIII). Intralesional interferon-alpha is usually not recommended because of high cost, difficult administration, and potential for systemic side effects (CIII). The rate of recurrence of genital warts is high despite treatment in HIV-infected patients. There is no consensus on the treatment of oral warts. Many treatments for anogenital warts cannot be used in the oral mucosa. Surgery is the most common treatment for oral warts that interfere with function or for aesthetic reasons. | |

Patient-Applied Therapy for Uncomplicated External Warts That Can Be Easily Identified by Patients:

| Provider-Applied Therapy for Complex or Multicentric Lesions, or Lesions Inaccessible to Patient Applied Therapy:

| ||

| Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Disease | ART regimen which includes 2 drugs that are active against both HBV and HIV is recommended for all HIV/HBV-co-infected patients regardless of CD4 cell count and HBV DNA level (AII). Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)/ emtricitabine or tenofovir disoproxil fumerate (TDF)/emtricitabine PO once daily (+ additional drug (s) for HIV) (AIII). The choice of TAF vs. TDF should be based on renal function and risk of renal or bone toxicities. CrCl > 60 mL/min CrCl 30-59 mL/min CrCl < 30 mL/min Duration: | If TAF or TDF Cannot Be Used as Part of HIV/HBV Therapy: Use entecavir (dose adjustment according to renal function) plus a fully suppressive ART regimen without TAF or TDF (BIII). CrCl < 30 mL/min If patient is not receiving ART:

| Chronic administration of lamivudine or emtricitabine as the only active drug against HBV should be avoided because of high rate of selection of HBV resistance (AI). Directly acting HBV drugs such as adefovir, emtricitabine, entecavir, lamivudine, telbivudine, or tenofovir must not be given in the absence of a fully suppressive ART regimen to avoid selection of drug resistance HIV (AI). When changing ART regimens, continue agents with anti-HBV activity (BIII). If anti-HBV therapy is discontinued and a flare occurs, therapy should be re-instituted because it can be potentially life-saving (AIII). As HBV reactivation can occur during treatment for HCV with directly active agents (DAAs) in the absence of HBV-active drugs, all HIV-HBV-coinfected patients who will be treated for HCV should be on HBV-active ART at the time of HCV treatment initiation (AII) |

| Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Disease | The field of HCV drug development is evolving rapidly. The armamenarium of approved drugs is likely to expand considerably in the next few years. Clinicians should refer to the most recent up-to-date HCV treatment guidelines (http://www.hcvguidelines.org) for the most updated recommendations. | ||

| Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML) (JC Virus Infections) | There is no specific antiviral therapy for JC virus infection. The main treatment approach is to reverse the immunosuppression caused by HIV. Initiate ART immediately in ART-naive patients (AII). Optimize ART in patients who develop PML in phase of HIV viremia on ART (AIII) | None. | Corticosteroids may be used for PML-IRIS characterized by contrast enhancement, edema or mass effect, and with clinical deterioration (BIII) (see text for further discussion). |

| Malaria | Because Plasmodium falciparum malaria can progress within hours from mild symptoms or low-grade fever to severe disease or death, all HIV-infected patients with confirmed or suspected P. falciparum infection should be hospitalized for evaluation, initiation of treatment, and observation (AIII). Treatment recommendations for HIV-infected patients are the same as HIV-uninfected patients (AIII). Choice of therapy is guided by the degree of parasitemia, the species of Plasmodium, the patient’s clinical status, region of infection, and the likely drug susceptibility of the infected species, and can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/malaria. | When suspicion for malaria is low, antimalarial treatment should not be initiated until the diagnosis is confirmed. | For treatment recommendations for specific regions, clinicians should refer to the following web link: http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/ or call the CDC Malaria Hotline: (770) 488-7788: M–F 8 AM–4:30 PM ET, or (770) 488-7100 after hours |

| Leishmaniasis, visceral | For Initial Infection:

Chronic Maintenance Therapy (Secondary Prophylaxis); Especially in Patients with CD4 Count <200 cells/µL:

| For Initial Infection:

Another Option:

Chronic Maintenance Therapy (Secondary Prophylaxis): | ART should be initiated or optimized (AIII). For sodium stibogluconate, contact the CDC Drug Service at (404) 639-3670 or [email protected] |

| Leishmaniasis, cutaneous |

Chronic Maintenance Therapy: | Possible Options Include:

No data exist for any of these agents in HIV-infected patients; choice and efficacy dependent on species of Leishmania. | None. |

| Chagas Disease (American Trypanosomiasis) | For Acute, Early Chronic, and Re-Activated Disease:

| For Acute, Early Chronic, And Reactivated Disease:

| Treatment is effective in reducing parasitemia and preventing clinical symptoms or slowing disease progression. It is ineffective in achieving parasitological cure. Duration of therapy has not been studied in HIV-infected patients. Initiate or optimize ART in patients undergoing treatment for Chagas disease, once they are clinically stable (AIII). |

| Penicilliosis marneffei | For Acute Infection in Severely Ill Patients:

For Mild Disease:

Chronic Maintenance Therapy (Secondary Prophylaxis):

| For Acute Infection in Severely Ill Patients:

For Mild Disease:

| ART should be initiated simultaneously with treatment for penicilliosis to improve treatment outcome (CIII). Itraconazole and voriconazole may have significant interactions with certain ARV agents. These interactions are complex and can be bi-directional. Refer to Table 5 for dosage recommendations. Therapeutic drug monitoring and dosage adjustment may be necessary to ensure triazole antifungal and ARV efficacy and reduce concentration-related toxicities. |

| Isosporiasis | For Acute Infection:

Chronic Maintenance Therapy (Secondary Prophylaxis):

| For Acute Infection:

Chronic Maintenance Therapy (Secondary Prophylaxis):

| Fluid and electrolyte management in patients with dehydration (AIII). Nutritional supplementation for malnourished patients (AIII). Immune reconstitution with ART may result in fewer relapses (AIII). |

| Abbreviations: ACTG = AIDS Clinical Trials Group; ART = antiretroviral therapy; ARV = antiretroviral; ATV/r = ritonavir-boosted atazanavir; BID = twice a day; BIW = twice weekly; BOC = boceprevir; CD4 = CD4 T lymphocyte cell; CDC = The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CFU = colony-forming unit; CNS = central nervous system; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; CYP3A4 = Cytochrome P450 3A4; ddI = didanosine; DOT = directly-observed therapy; DS = double strength; EFV = efavirenz; EMB = ethambutol; g = gram; G6PD = Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; GI = gastrointestinal; ICP = intracranial pressure; ICU = intensive care unit; IM = intramuscular; IND = investigational new drug; INH = isoniazid; IRIS = immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; IV = intravenous; LP = lumbar puncture; mg = milligram; mmHg = millimeters of mercury; NNRTI = non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NRTI = nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PegIFN = Pegylated interferon; PI = protease inhibitor; PO = oral; PORN = Progressive Outer Retinal Necrosis; PZA = pyrazinamide; qAM = every morning; QID = four times a day; q(n)h = every “n” hours; qPM = every evening; RBV = ribavirin; RFB = rifabutin; RIF = rifampin; SQ = subcutaneous; SS = single strength; TID = three times daily; TVR = telaprevir; TMP-SMX = trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; ZDV = zidovudine a Refer to http://www.daraprimdirect.com for information regarding how to access pyrimethamine Evidence Rating: Quality of Evidence for the Recommendation: In cases where there are no data for the prevention or treatment of an OI based on studies conducted in HIV-infected populations, but data derived from HIV-uninfected patients exist that can plausibly guide management decisions for patients with HIV/AIDS, the data will be rated as III but will be assigned recommendations of A, B, C depending on the strength of recommendation. | |||

Table 4. Summary of Pre-Clinical and Human Data on, and Indications for, Opportunistic Infection Drugs During Pregnancy

| Drug | FDA Category | Pertinent Animal Reproductive and Human Pregnancy Data | Recommended Use During Pregnancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acyclovir | B | No teratogenicity in mice, rats, rabbits at human levels. Large experience in pregnancy (>700 first-trimester exposures reported to registry); well-tolerated. | Treatment of frequent or severe symptomatic herpes outbreaks or varicella |

| Adefovir | C | No increase in malformations at 23 times (rats) and 40 times (rabbits) human dose. Limited experience with human use in pregnancy. | Not recommended because of limited data in pregnancy. Report exposures during pregnancy to Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry: http://www.APRegistry.com |

| Albendazole | C | Embryotoxic and teratogenic (skeletal malformations) in rats and rabbits, but not in mice or cows. Limited experience in human pregnancy. | Not recommended, especially in first trimester. Primary therapy for microsporidiosis in pregnancy should be ART. |

| Amikacin | C | Not teratogenic in mice, rats, rabbits. Theoretical risk of ototoxicity in fetus; reported with streptomycin but not amikacin. | Drug-resistant TB, severe MAC infections |

| Amoxicillin, amox./ clavulanate, ampicillin/ sulbactam | B | Not teratogenic in animals. Large experience in human pregnancy does not suggest an increase in adverse events. | Susceptible bacterial infections |

| Amphotericin B | B | Not teratogenic in animals or in human experience. Preferred over azole antifungals in first trimester if similar efficacy expected. | Documented invasive fungal disease |

| Antimonials, pentavalent (stibogluconate, meglumine) | Not FDA approved | Antimony not teratogenic in rats, chicks, sheep. Three cases reported of use in human pregnancy in second trimester with good outcome. Labeled as contraindicated in pregnancy. | Therapy of visceral leishmaniasis not responsive to amphotericin B or pentamidine |

| Artesunate, artemether, artemether/ lumefantrine | C | Embryotoxicity, cardiovascular and skeletal anomalies in rats and rabbits. Embryotoxic in monkeys. Human experience, primarily in the second and third trimesters, has not identified increased adverse events. | Recommended by WHO as first-line therapy in second/third trimester for P. falciparum and severe malaria. Pending more data, use for malaria in first trimester only if other drugs not available or have failed. Report cases of exposure to WHO Anti-malarial Pregnancy Exposure Registry when available. |

| Atovaquone | C | Not teratogenic in rats or rabbits, limited human experience | Alternate agent for PCP, Toxoplasma gondii, malaria infections |

| Azithromycin | B | Not teratogenic in animals. Moderate experience with use in human pregnancy does not suggest adverse events. | Preferred agent for MAC prophylaxis or treatment (with ethambutol), Chlamydia trachomatis infection in pregnancy. |

| Aztreonam | B | Not teratogenic in rats, rabbits. Limited human experience, but other beta-lactam antibiotics have not been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. | Susceptible bacterial infections |

| Bedaquiline | B | Not teratogenic in rats, rabbits. No experience in human pregnancy. | Multidrug resistant TB when effective treatment regimen can not otherwise be provided. |

| Benznidazole | Not FDA approved | No animal studies. Increase in chromosomal aberrations in children with treatment; uncertain significance. No human pregnancy data. | Not indicated for chronic T. cruzi in pregnancy. Seek expert consultation if acute or symptomatic infection in pregnancy requiring treatment. |

| Boceprevir | B | Not teratogenic in rats, rabbits. No human pregnancy data. | Treatment of HCV currently generally not indicated in pregnancy. |

| Capreomycin | C | Increase in skeletal variants in rats. Limited experience in human pregnancy; theoretical risk of fetal ototoxicity. | Drug-resistant TB |

| Caspofungin | C | Embryotoxic, skeletal defects in rats, rabbits. No experience with human use. | Invasive Candida or Aspergillus infections refractory to amphotericin and azoles |

| Cephalosporins | B | Not teratogenic in animals. Large experience in human pregnancy has not suggested increase in adverse outcomes. | Bacterial infections; alternate treatment for MAC |

| Chloroquine | C | Associated with anophthalmia, micro-ophthalmia at fetotoxic doses in animals. Not associated with increased risk in human pregnancy at doses used for malaria. | Drug of choice for malaria prophylaxis and treatment of sensitive species in pregnancy. |

| Cidofovir | C | Embryotoxic and teratogenic (meningocele, skeletal abnormalities) in rats and rabbits. No experience in human pregnancy. | Not recommended |

| Ciprofloxacin, other quinolones | C | Arthropathy in immature animals; not embryotoxic or teratogenic in mice, rats, rabbits, or monkeys. More than 1100 cases of quinolone use in human pregnancy have not been associated with arthropathy or birth defects. | Severe MAC infections; multidrug resistant TB, anthrax, bacterial infections |

| Clarithromycin | C | Cardiovascular defects noted in one strain of rats and cleft palate in mice at high doses, not teratogenic in rabbits or monkeys. Two human studies, each with >100 first-trimester exposures, did not show increase in defects but one study found an increase in spontaneous abortion. | Treatment or secondary MAC prophylaxis, if other choices exhausted |

| Clindamycin | B | No concerns specific to pregnancy in animal or human studies. | Treatment of anaerobic bacterial infections and used with quinine for chloroquine-resistant malaria; alternate agent for secondary prophylaxis of Toxoplasma encephalitis |

| Clofazimine | C | Not teratogenic in mice, rats, or rabbits. Limited experience reported (19 cases); no anomalies noted but red-brown skin discoloration reported in several infants exposed throughout pregnancy. | No indications. |

| Clotrimazole troches | C | Not teratogenic in animals at exposures expected from treatment of oral or vaginal Candida. No increase in adverse pregnancy outcomes with vaginal use. | Oral or vaginal Candida infections and prophylaxis |

| Cycloserine | C | Not teratogenic in rats. No data available from human studies. | Drug-resistant TB |

| Dapsone | C | No animal data. Limited human experience does not suggest teratogenicity; might displace bound bilirubin in the neonate, increasing the risk of kernicterus. Case reports of hemolytic anemia in fetus/infant with maternal treatment. | Alternate choice for primary or secondary PCP prophylaxis |

| Diphenoxylate | C | Limited animal and human data do not indicate teratogenicity. | Symptomatic treatment of diarrhea |

| Doxycycline, other tetracyclines | D | Risk of hepatic toxicity increased with tetracyclines in pregnancy; staining of fetal bones and teeth contraindicates use in pregnancy. | No indications |

| Emtricitabine | B | No concerns in pregnancy from limited animal and human data. | As part of fully suppressive combination antiretroviral regimen for treatment of HIV, HBV. Report exposures during pregnancy to Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry: http://www.APRegistry.com. |

| Entecavir | C | Animal data do not suggest teratogenicity at human doses; limited experience in human pregnancy. | Not recommended because of limited data in pregnancy. Use as part of fully suppressive ARV regimen with ARV agents active against both HIV and HBV. Report exposures during pregnancy to Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry: http://www.APRegistry.com. |

| Erythromycin | B | Hepatotoxicity with erythromycin estolate in pregnancy; other forms acceptable; no evidence of teratogenicity | Bacterial and chlamydial infections |

| Ethambutol | B | Teratogenic, at high doses, in mice, rats, rabbits. No evidence of teratogenicity in 320 cases of human use for treatment of TB. | Active TB and MAC treatment; avoid in first trimester if possible |

| Ethionamide | C | Increased rate of defects (omphalocele, exencephaly, cleft palate) in rats, mice, and rabbits with high doses; not seen with usual human doses. Limited human data; case reports of CNS defects. | Active TB; avoid in first trimester if possible |

| Famciclovir | B | No evidence of teratogenicity in rats or rabbits, limited human experience. | Recurrent genital herpes and primary varicella infection. Report exposures during pregnancy to the Famvir Pregnancy Registry (1-888-669-6682). |

| Fluconazole | C | Abnormal ossification, structural defects in rats, mice at high doses. Case reports of rare pattern of craniofacial, skeletal and other abnormalities in five infants born to four women with prolonged exposure during pregnancy; no increase in defects seen in several series after single dose treatment. | Single dose may be used for treatment of vaginal Candida though topical therapy preferred. Not recommended for prophylaxis during early pregnancy. Can be used for invasive fungal infections after first trimester; amphotericin B preferred in first trimester if similar efficacy expected. |

| Flucytosine | C | Facial clefts and skeletal defects in rats; cleft palate in mice, no defects in rabbits. No reports of use in first trimester of human pregnancy; may be metabolized to 5-fluorouracil, which is teratogenic in animals and possibly in humans. | Use after first trimester if indicated for life-threatening fungal infections. |

| Foscarnet | C | Skeletal variants in rats, rabbits and hypoplastic dental enamel in rats. Single case report of use in human pregnancy in third trimester. | Alternate agent for treatment or secondary prophylaxis of life-threatening or sight-threatening CMV infection. |

| Fumagillin | Not FDA approved | Caused complete litter destruction or growth retardation in rats, depending on when administered. No data in human pregnancy. | Topical solution can be used for ocular microsporidial infections. |

| Ganciclovir, valganciclovir | C | Embryotoxic in rabbits and mice; teratogenic in rabbits (cleft palate, anophthalmia, aplastic kidney and pancreas, hydrocephalus). Case reports of safe use in human pregnancy after transplants, treatment of fetal CMV. | Treatment or secondary prophylaxis of life-threatening or sight-threatening CMV infection. Preferred agent for therapy in children. |

| Imipenem, meropenem | C/B | Not teratogenic in animals; limited human experience. | Serious bacterial infections |

| Imiquimod | B | Not teratogenic in rats and rabbits; 8 case reports of human use, only 2 in first trimester. | Because of limited experience, other treatment modalities such as cryotherapy or trichloracetic acid recommended for wart treatment during pregnancy. |

| Influenza vaccine | C | Not teratogenic. Live vaccines, including intranasal influenza vaccine, are contraindicated in pregnancy. | All pregnant women should receive injectable influenza vaccine because of the increased risk of complications of influenza during pregnancy. Ideally, HIV-infected women should be on ART before vaccination to limit potential increases in HIV RNA levels with immunization. |

| Interferons (alfa, beta, gamma) | C | Abortifacient at high doses in monkeys, mice; not teratogenic in monkeys, mice, rats, or rabbits. Approximately 30 cases of use of interferon-alfa in pregnancy reported; 14 in first trimester without increase in anomalies; possible increased risk of intrauterine growth retardation. | Not indicated. Treatment of HCV currently generally not recommended in pregnancy. |

| Isoniazid | C | Not teratogenic in animals. Possible increased risk of hepatotoxicity during pregnancy; prophylactic pyridoxine, 50 mg/day, should be given to prevent maternal and fetal neurotoxicity. | Active TB; prophylaxis for exposure or skin test conversion |

| Itraconazole | C | Teratogenic in rats and mice at high doses. Case reports of craniofacial, skeletal abnormalities in humans with prolonged fluconazole exposure during pregnancy; no increase in defect rate noted among over 300 infants born after first-trimester itraconazole exposure. | Only for documented systemic fungal disease, not prophylaxis. Consider using amphotericin B in first trimester if similar efficacy expected. |

| Kanamycin | D | Associated with club feet in mice, inner ear changes in multiple species. Hearing loss in 2.3% of 391 children after long-term in utero therapy. | Drug-resistant TB |

| Ketoconazole | C | Teratogenic in rats, increased fetal death in mice, rabbits. Inhibits androgen and corticosteroid synthesis; may impact fetal male genital development; case reports of craniofacial, skeletal abnormalities in humans with prolonged fluconazole exposure during pregnancy. | None |

| Lamivudine | C | Not teratogenic in animals. No evidence of teratogenicity with >3700 first-trimester exposures reported to Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry. | HIV and HBV therapy, only as part of a fully suppressive combination ARV regimen. Report exposures to Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry: http://www.APRegistry.com. |

| Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir | B | No evidence of teratogenicity in rats or rabbits. No experience in human pregnancy. | Treatment of hepatitis C generally not indicated in pregnancy. |

| Leucovorin (folinic acid) | C | Prevents birth defects of valproic acid, methotrexate, phenytoin, aminopterin in animal models. No evidence of harm in human pregnancies. | Use with pyrimethamine if use of pyrimethamine cannot be avoided. |

| Linezolid | C | Not teratogenic in animals. Decreased fetal weight and neonatal survival at ~ human exposures, possibly related to maternal toxicity. Limited human experience. | Serious bacterial infections |

| Loperamide | B | Not teratogenic in animals. No increase in birth defects among infants born to 89 women with first-trimester exposure in one study; another study suggests a possible increased risk of hypospadias with first-trimester exposure, but confirmation required. | Symptomatic treatment of diarrhea after the first trimester |

| Mefloquine | C | Animal data and human data do not suggest an increased risk of birth defects, but miscarriage and stillbirth may be increased. | Second-line therapy of chloroquine-resistant malaria in pregnancy, if quinine/clindamycin not available or not tolerated. Weekly as prophylaxis in areas with chloroquine-resistant malaria. |

| Meglumine | Not FDA approved | See Antimonials, pentavalent | |

| Metronidazole | B | Multiple studies do not indicate teratogenicity. Studies on several hundred women with first-trimester exposure found no increase in birth defects. | Anaerobic bacterial infections, bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis, giardiasis, amebiasis |

| Micafungin | C | Teratogenic in rabbits; no human experience. | Not recommended |

| Miltefosine | Not FDA approved | Embryotoxic in rats, rabbits; teratogenic in rats. No experience with human use. | Not recommended |

| Nifurtimox | Not FDA approved | Not teratogenic in mice and rats. Increased chromosomal aberrations in children receiving treatment; uncertain significance. No experience in human pregnancy. | Not indicated in chronic infection; seek expert consultation if acute infection or symptomatic reactivation of T. cruzi in pregnancy. |

| Nitazoxanide | B | Not teratogenic in animals; no human data | Severely symptomatic cryptosporidiosis after the first trimester |

| Para-amino salicylic acid (PAS) | C | Occipital bone defects in one study in rats; not teratogenic in rabbits. Possible increase in limb, ear anomalies in one study with 143 first-trimester exposures; no specific pattern of defects noted, several studies did not find increased risk. | Drug-resistant TB |

| Paromomycin | C | Not teratogenic in mice and rabbits. Limited human experience, but poor oral absorption makes toxicity, teratogenicity unlikely. | Amebic intestinal infections, possibly cryptosporidiosis |

| Penicillin | B | Not teratogenic in multiple animal species. Vast experience with use in human pregnancy does not suggest teratogenicity, other adverse outcomes. | Syphilis, other susceptible bacterial infections |

| Pentamidine | C | Embryocidal but not teratogenic in rats, rabbits with systemic use. Limited experience with systemic use in pregnancy. | Alternate therapy for PCP and leishmaniasis. |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | B | Not teratogenic in limited animal studies. Limited experience in pregnancy but penicillins generally considered safe. | Bacterial infections |

| Pneumococcal vaccine | C | No studies in animal pregnancy. Polysaccharide vaccines generally considered safe in pregnancy. Well-tolerated in third-trimester studies. | Initial or booster dose for prevention of invasive pneumococcal infections. HIV-infected pregnant women should be on ART before vaccination to limit potential increases in HIV RNA levels with immunization. |

| Podophyllin, podofilox | C | Increased embryonic and fetal deaths in rats, mice but not teratogenic. Case reports of maternal, fetal deaths after use of podophyllin resin in pregnancy; no clear increase in birth defects with first-trimester exposure. | Because alternative treatments for genital warts in pregnancy are available, use not recommended; inadvertent use in early pregnancy is not indication for abortion. |

| Posaconazole | C | Embryotoxic in rabbits; teratogenic in rats at similar to human exposures. No experience in human pregnancy. | Not recommended |

| Prednisone | B | Dose-dependent increased risk of cleft palate in mice, rabbits, hamsters; dose-dependent increase in genital anomalies in mice. Human data inconsistent regarding increased risk of cleft palate. Risk of growth retardation, low birth weight may be increased with chronic use; monitor for hyperglycemia with use in third trimester. | Adjunctive therapy for severe PCP; multiple other non-HIV-related indications |

| Primaquine | C | No animal data. Limited experience with use in human pregnancy; theoretical risk for hemolytic anemia if fetus has G6PD deficiency. | Alternate therapy for PCP, chloroquine-resistant malaria |

| Proguanil | C | Not teratogenic in animals. Widely used in malaria-endemic areas with no clear increase in adverse outcomes. | Alternate therapy and prophylaxis of P. falciparum malaria |

| Pyrazinamide | C | Not teratogenic in rats, mice. Limited experience with use in human pregnancy. | Active TB |

| Pyrimethamine | C | Teratogenic in mice, rats, hamsters (cleft palate, neural tube defects, and limb anomalies). Limited human data have not suggested an increased risk of birth defects; because folate antagonist, use with leucovorin. | Treatment and secondary prophylaxis of toxoplasmic encephalitis; alternate treatment of PCP |

| Quinidine gluconate | C | Generally considered safe in pregnancy; high doses associated with preterm labor. One case of fetal 8th nerve damage reported. | Alternate treatment of malaria, control of fetal arrhythmias |