Axillary lymphadenopathy

Axillary lymphadenopathy is a medical term for armpit lymph nodes that are abnormal in size (e.g., greater than 1 cm) or consistency. Axillary lymph nodes drain your hand, arm, lateral chest, abdominal walls, and the lateral portion of your breast. Causes of lymphadenopathy can be remembered with the MIAMI mnemonic: malignancies, infections, autoimmune disorders, miscellaneous and unusual conditions, and iatrogenic causes 1. In most cases, the history and physical examination alone identify the cause. An armpit lump in a woman may be a sign of breast cancer, and it should be checked by a doctor right away. See your physician if you have an unexplained armpit lump. Do not try to diagnose axillary lymphadenopathy or armpit lumps by yourself!

A common cause of axillary lymphadenopathy is catscratch disease. Local axillary skin infection and irritation commonly are associated with local lymphadenopathy. Other causes include recent immunizations in the arm (particularly with bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine), brucellosis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

In primary care practice, the annual incidence of unexplained lymphadenopathy is 0.6% 2. Only 1.1% of these cases are related to malignancy, but this percentage increases with advancing age 2. Cancers are identified in 4% of patients 40 years and older who present with unexplained lymphadenopathy vs. 0.4% of those younger than 40 years 2.

Hard or matted lymph nodes may suggest malignancy or infection 3. Hidradenitis suppurativa is a condition of enlarged tender lymph nodes that typically affects children with obesity and is caused by recurrent abscesses of lymph nodes in the axillary chain. The cause is unknown, and treatment may include antibiotics. Many patients require incision and drainage.

Factors that can assist in identifying the cause of lymphadenopathy include patient age, duration of lymphadenopathy, exposures, associated symptoms, and location (localized vs. generalized). Table 1 lists common historical clues and their associated diagnoses 4. Other historical questions include asking about time course of enlargement, tenderness to palpation, recent infections, recent immunizations, and medications 5.

The workup may include blood tests, imaging, and biopsy depending on clinical presentation, location of the lymphadenopathy, and underlying risk factors. Biopsy options include fine-needle aspiration, core needle biopsy, or open excisional biopsy. Antibiotics may be used to treat acute unilateral cervical lymphadenitis, especially in children with systemic symptoms. Corticosteroids have limited usefulness in the management of unexplained lymphadenopathy and should not be used without an appropriate diagnosis.

Figure 1. Axillary lymphadenopathy possible causes

[Source 3 ]Table 1. Clues and initial testing to determine the cause of lymphadenopathy

| Historical clues | Suggested diagnoses | Initial testing | |

|---|---|---|---|

Fever, night sweats, weight loss, or node located in supraclavicular, popliteal, or iliac region, bruising, splenomegaly | Leukemia, lymphoma, solid tumor metastasis | CBC, nodal biopsy or bone marrow biopsy; imaging with ultrasonography or computed tomography may be considered but should not delay referral for biopsy | |

Fever, chills, malaise, sore throat, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea; no other red flag symptoms | Bacterial or viral pharyngitis, hepatitis, influenza, mononucleosis, tuberculosis (if exposed), rubella | Limited illnesses may not require any additional testing; depending on clinical assessment, consider CBC, monospot test, liver function tests, cultures, and disease-specific serologies as needed | |

High-risk sexual behavior | Chancroid, HIV infection, lymphogranuloma venereum, syphilis | HIV-1/HIV-2 immunoassay, rapid plasma reagin, culture of lesions, nucleic acid amplification for chlamydia, migration inhibitory factor test | |

Animal or food contact | |||

Cats | Cat-scratch disease (Bartonella) | Serology and polymerase chain reaction | |

Toxoplasmosis | Serology | ||

Rabbits, or sheep or cattle wool, hair, or hides | Anthrax | Per CDC guidelines | |

Brucellosis | Serology and polymerase chain reaction | ||

Tularemia | Blood culture and serology | ||

Undercooked meat | Anthrax | Per CDC guidelines | |

Brucellosis | Serology and polymerase chain reaction | ||

Toxoplasmosis | Serology | ||

Recent travel, insect bites | Diagnoses based on endemic region | Serology and testing as indicated by suspected exposure | |

Arthralgias, rash, joint stiffness, fever, chills, muscle weakness | Rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, dermatomyositis, systemic lupus erythematosus | Antinuclear antibody, anti-doubled-stranded DNA, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CBC, rheumatoid factor, creatine kinase, electromyography, or muscle biopsy as indicated | |

Abbreivations: CBC = complete blood count; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

[Source 3 ]What are lymph nodes?

The lymph node functions as an antigen filter for the reticuloendothelial system of the body 6. Lymph node consists of a multi-layered sinus that sequentially exposes B-cell lymphocytes, T-cell lymphocytes, and macrophages to an afferent extracellular fluid. In this way, the immune system can recognize and react to foreign proteins and mount an immune response or sequester these proteins as appropriate. In the course of this reaction, there is some multiplication of the responding immune cell line, and thus, the node itself increases in size. It is generally held that a lymph node size is considered enlarged (lymphadenopathy) when it is larger than 1 cm 6. However, the reality is that “normal” and “enlarged” criteria vary depending on the location of the lymph node and the age of the patient. For example, children younger than 10 years of age have more hypertrophic immune systems and lymph nodes up to 2 cm can be considered normal in some clinical situations yet, an epitrochlear lymph node of above 0.5 cm is considered pathological in an adult 6.

The pattern, distribution, and quality of the lymphadenopathy can provide much clinical information in the diagnostic process. Lymphadenopathy occurs in 2 patterns: generalized and localized. Generalized lymphadenopathy entails lymphadenopathy in 2 or more non-contiguous locations. Localized adenopathy occurs in contiguous groupings of lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are distributed in discrete anatomical areas, and their enlargement reflects the lymphatic drainage of their location. The lymph nodes themselves may be tender or non-tender, fixed or mobile, and discreet or “matted” together. Concomitant symptomatology and the epidemiology of the patient and the illness provide further diagnostic cues. A thorough history of any prodromal illness, fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss, and localizing symptoms can be very revealing. Additionally, the demographic particulars of the patient, including age, gender, exposure to infectious disease, toxins, medications, and their habits may provide further cues.

Generalized lymphadenopathy

Generalized lymphadenopathy is the enlargement of more than two noncontiguous lymph node groups 7. Significant systemic disease from infections, autoimmune diseases, or disseminated malignancy often causes generalized lymphadenopathy, and specific testing is necessary to determine the diagnosis. Benign causes of generalized lymphadenopathy are self-limited viral illnesses, such as infectious mononucleosis, and medications. Other causes include acute human immunodeficiency virus infection, activated mycobacterial infection, cryptococcosis, cytomegalovirus, Kaposi sarcoma, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Generalized lymphadenopathy can occur with leukemias, lymphomas, and advanced metastatic carcinomas 8.

Axillary lymphadenopathy causes

Lumps in the armpit may have many causes. Axillary lymph nodes drain the hand, arm, lateral chest, abdominal walls, and the lateral portion of the breast. Lymph nodes act as filters that can catch germs or cancerous tumor cells. When they do, lymph nodes increase in size and are easily felt. Reasons lymph nodes in the armpit area may be enlarged are:

- Arm or breast infection

- Some bodywide infections, such as mono, AIDS, or herpes

- Cancers, such as lymphomas or breast cancer

Cysts or abscesses under the skin may also produce large, painful lumps in the armpit. These may be caused by shaving or use of antiperspirants (not deodorants). This is most often seen in teens just beginning to shave.

Other causes of armpit lumps may include:

- Cat scratch disease

- Lipomas (harmless fatty growths)

- Use of certain medicines or vaccinations

MIAMI Mnemonic for Differential Diagnosis of Lymphadenopathy 4

- Malignancies: Kaposi sarcoma, leukemias, lymphomas, metastases, skin neoplasms

- Infections:

- Bacterial: brucellosis, cat-scratch disease (Bartonella), chancroid, cutaneous infections (staphylococcal or streptococcal), lymphogranuloma venereum, primary and secondary syphilis, tuberculosis, tularemia, typhoid fever

- Granulomatous: berylliosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, silicosis

- Viral: adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis, herpes zoster, human immunodeficiency virus, infectious mononucleosis (Epstein-Barr virus), rubella

- Other: fungal, helminthic, Lyme disease, rickettsial, scrub typhus, toxoplasmosis

- Autoimmune disorders: Dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, Still disease, systemic lupus erythematosus

- Miscellaneous/unusual conditions: Angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman disease), histiocytosis, Kawasaki disease, Kikuchi lymphadenitis, Kimura disease, sarcoidosis

- Iatrogenic causes: Medications, serum sickness

Lymphadenopathy is benign and self-limited in most patients 3. Axillary lymphadenopathy causes include malignancy, infection, and autoimmune disorders, as well as medications and iatrogenic causes 3. When the cause is unknown, lymphadenopathy should be classified as localized or generalized. Patients with localized lymphadenopathy should be evaluated for causes typically associated with the region involved according to lymphatic drainage patterns. Generalized lymphadenopathy, defined as two or more involved regions, often indicates underlying systemic disease. Risk factors for malignancy include age older than 40 years, male sex, white race, supraclavicular location of the nodes, and presence of systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and unexplained weight loss. Palpable supraclavicular, popliteal, and iliac nodes are abnormal, as are epitrochlear nodes greater than 5 mm in diameter.

Infections or injuries of the upper extremities are a common cause of axillary lymphadenopathy 3. Common infectious causes are cat-scratch disease, tularemia, and sporotrichosis due to inoculation and lymphatic drainage. Local axillary skin infection and irritation commonly are associated with local axillary lymphadenopathy. Absence of an infectious source or traumatic lesions is highly suspicious for a malignant cause such as Hodgkin lymphoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Breast, lung, thyroid, stomach, colorectal, pancreatic, ovarian, kidney, and skin cancers (malignant melanoma) can metastasize to the axilla 8. Silicone breast implants may also cause axillary lymphadenopathy because of an inflammatory reaction to silicone particles from implant leakage 9.

Other causes include recent immunizations in the arm (particularly with bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine), brucellosis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and hidradenitis suppurativa. Hidradenitis suppurativa is a condition of enlarged tender lymph nodes that typically affects children with obesity and is caused by recurrent abscesses of lymph nodes in the axillary chain. The etiology is unknown, and treatment may include antibiotics. Many patients require incision and drainage.

Palpable supraclavicular, popliteal, and iliac nodes, and epitrochlear lymph nodes greater than 5 mm, are considered abnormal. Etiologies of lymphadenopathy can be remembered with the MIAMI mnemonic: malignancies, infections, autoimmune disorders, miscellaneous and unusual conditions, and iatrogenic causes 8. In most cases, the history and physical examination alone identify the cause.

Factors that can assist in identifying the cause of lymphadenopathy include patient age, duration of lymphadenopathy, exposures, associated symptoms, and location (localized vs. generalized). Table 1 lists common historical clues and their associated diagnoses 4. Other historical questions include asking about time course of enlargement, tenderness to palpation, recent infections, recent immunizations, and medications 5.

Age and duration

About one-half of otherwise healthy children have palpable lymph nodes at any one time 5. Most lymphadenopathy in children is benign or infectious in etiology. In adults and children, lymphadenopathy lasting less than two weeks or greater than 12 months without change in size has a low likelihood of being neoplastic 10. Exceptions include low-grade Hodgkin lymphomas and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, although both typically have associated systemic symptoms 11.

Exposures

Environmental, travel-related, animal, and insect exposures should be ascertained. Chronic medication use, infectious exposures, immunization status, and recent immunizations should be reviewed as well. See list of medications commonly associated with lymphadenopathy below 1. Tobacco and alcohol use and ultraviolet radiation exposure increase concerns for neoplasm. An occupational history that includes mining, masonry, and metal work may elicit work-related etiologies of lymphadenopathy, such as silicon or beryllium exposure. Asking about sexual history to assess exposure to genital sores or participation in oral intercourse is important, especially for inguinal and cervical lymphadenopathy. Finally, family history may identify familial causes of lymphadenopathy, such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome or lipid storage diseases 1.

Medications that can cause lymphadenopathy 1:

- Allopurinol

- Atenolol

- Captopril

- Carbamazepine (Tegretol)

- Gold

- Hydralazine

- Penicillins

- Phenytoin (Dilantin)

- Primidone (Mysoline)

- Pyrimethamine (Daraprim)

- Quinidine

- Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

- Sulindac

Associated symptoms

A thorough review of systems aids in identifying any red flag symptoms. Arthralgias, muscle weakness, and rash suggest an autoimmune etiology. Constitutional symptoms of fever, chills, fatigue, and malaise indicate an infectious etiology. In addition to fever, drenching night sweats and unexplained weight loss of greater than 10% of body weight may suggest Hodgkin lymphoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma 11.

Risk factors for malignancy

- Age older than 40 years

- Duration of lymphadenopathy greater than four to six weeks

- Generalized lymphadenopathy (two or more regions involved)

- Male sex

- Lymph node not returned to baseline after eight to 12 weeks

- Supraclavicular location

- Systemic signs: fever, night sweats, weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly

- White race

Axillary lymphadenopathy diagnosis

As evidenced above, the critical step in evaluation for axillary lymphadenopathy is a careful history and focused physical exam. The extent of the history and physical is determined by the clinical presentation of the patient.

Your doctor will examine you and gently press on the nodes. You will be asked questions about your medical history and symptoms, such as:

- When did you first notice the lump? Has the lump changed?

- Are you breastfeeding?

- Is there anything that makes the lump worse?

- Is the lump painful?

- Do you have any other symptoms?

You may need more tests, depending on the results of your physical exam.

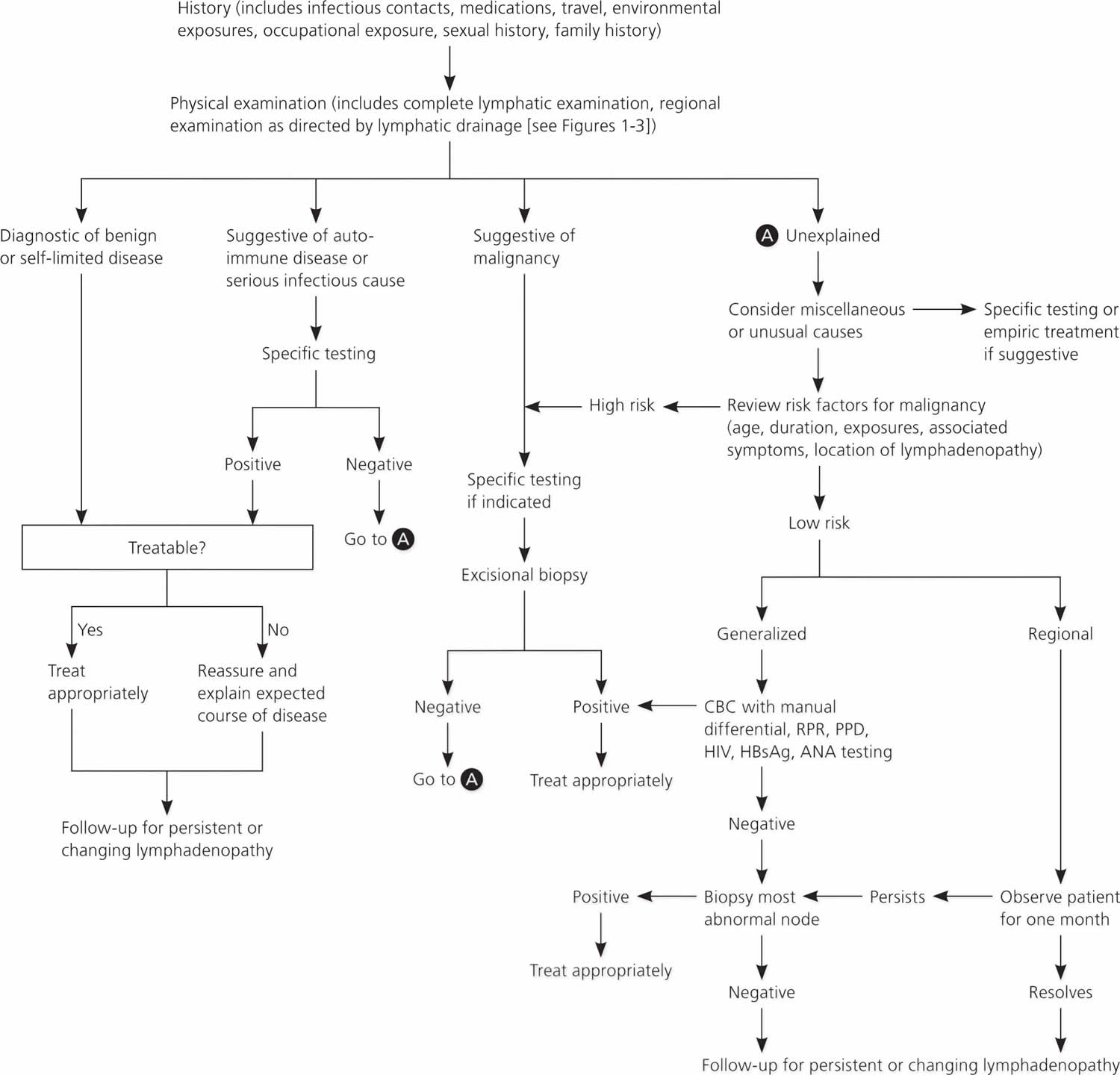

Figure 2 provides an algorithm for evaluating lymphadenopathy 1. If history and physical examination findings suggest a benign or self-limited process, reassurance can be provided and follow-up arranged if lymphadenopathy persists. Findings suggestive of infectious or autoimmune etiologies may require specific testing and treatment as indicated. If malignancy is considered unlikely based on history and physical examination, localized lymphadenopathy can be observed for four weeks. Generalized lymphadenopathy should prompt routine laboratory testing and testing for autoimmune and infectious causes 1.

Overall state of health and height and weight measurements may help identify signs of chronic disease, especially in children 12. A complete lymphatic examination should be performed to rule out generalized lymphadenopathy, followed by a focused lymphatic examination with consideration of lymphatic drainage patterns. Figure 1 demonstrates typical axillary lymphatic drainage patterns, as well as common causes of lymphadenopathy in these regions 1. A skin examination should be performed to rule out other lesions that would point to malignancy and to evaluate for erythematous lines along nodal tracts or any trauma that could lead to an infectious source of the lymphadenopathy. Finally, abdominal examination focused on splenomegaly, although rarely associated with lymphadenopathy, may be useful for detecting infectious mononucleosis, lymphocytic leukemias, lymphoma, or sarcoidosis 1.

For example, a patient with posterior cervical adenopathy sore throat and tremendous fatigue needs only a careful history, cursory examination and a mono test, while a person with generalized lymphadenopathy and fatigue would require a much more extensive investigation. Generally, the majority of the lymphadenopathy is localized (some site a 3:1 ratio), with the majority of that being represented in the head and neck region (again some site a 3:1 ratio). It also is accepted, that all generalized lymphadenopathy merits clinical evaluation and the presence of “matted lymphadenopathy” is strongly indicative of significant pathology.Examination of the patient’s history, physical examination, and the demographic in which they fall can allow the patient to be placed into 1 of several different accepted algorithms for workup of lymphadenopathy. The use of these cues and selection of the correct arm of the algorithm allows for fairly rapid and cost-effective diagnosis of lymphadenopathy including determination when it is safe to observe 13.

Radiologic evaluation with computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or ultrasonography may help to characterize lymphadenopathy. The American College of Radiology recommends ultrasonography as the initial imaging choice for cervical lymphadenopathy in children up to 14 years of age and computed tomography for persons older than 14 years 14. Based on the location of the abnormal nodes, the sensitivity of these modalities for diagnosing metastatic lymph nodes varies; therefore, history and clinical examination must guide selection 15. If the diagnosis is still uncertain, biopsy is recommended.

In children with acute unilateral anterior cervical lymphadenitis and systemic symptoms, antibiotics may be prescribed. Empiric antibiotics should target Staphylococcus aureus and group A streptococci. Options include oral cephalosporins, amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin), orclindamycin 16. Corticosteroids should be avoided until a definitive diagnosis is made because treatment could potentially mask or delay histologic diagnosis of leukemia or lymphoma 10.

Biopsy

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and core needle biopsy can aid in the diagnostic evaluation of lymph nodes when cause is unknown or malignant risk factors are present 5. Fine-needle aspiration cytology is a quick, accurate, minimally invasive, and safe technique to evaluate patients and aid in triage of unexplained lymphadenopathy 17. If a reactive lymph node is likely, core needle biopsy can be avoided, and fine-needle aspiration used alone. Combined, they allow cytologic and histopathologic assessment of lymph nodes. However, the use of both techniques may not be needed because the diagnostic accuracy of fine-needle aspiration (FNA) in adult populations has been reported to approach 90%, with a sensitivity and specificity of 85% to 95% and 98% to 100%, respectively 18. False-positive diagnoses are rare with fine-needle aspiration. False-negative results occur secondary to early or partial involvement of lymph nodes, inexperience with lymph node cytology, unrecognized lymphomas with heterogeneity, and sampling errors 19. There are concerns about the reliability of fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of diseases such as lymphoma because it is unable to assess lymph node architecture. Regardless, fine-needle aspiration may be a useful triage tool for differentiating benign reactive lymphadenopathy from malignancy 20.

Open excisional biopsy remains a diagnostic option for patients who do not wish to undergo additional procedures. When selecting nodes for any method, the largest, most suspicious, and most accessible node should be sampled. Inguinal nodes typically display the lowest yield, and supraclavicular nodes have the highest 21.

Figure 2. Axillary lymphadenopathy diagnostic algorithm

Abbreviations: ANA = antinuclear antibody; CBC = complete blood count; HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen; HIV = human immunodeficienty virus; PPD = purified protein derivative; RPR = rapid plasma reagin

[Source 3 ]Axillary lymphadenopathy treatment

Axillary lymphadenopathy treatment is determined by the specific underlying cause of axillary lymphadenopathy.

References- Bazemore AW, Smucker DR. Lymphadenopathy and malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(11):2103–2110.

- Fijten GH, Blijham GH. Unexplained lymphadenopathy in family practice. An evaluation of the probability of malignant causes and the effectiveness of physicians’ workup. J Fam Pract. 1988;27(4):373–376.

- Unexplained Lymphadenopathy: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Dec 1;94(11):896-903. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2016/1201/p896.html

- Bazemore AW, Smucker DR. Lymphadenopathy and malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(11):2103–2110

- King D, Ramachandra J, Yeomanson D. Lymphadenopathy in children: refer or reassure? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2014;99(3):101–110.

- Freeman AM, Matto P. Adenopathy. [Updated 2019 Nov 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513250

- Ferrer R. Lymphadenopathy: differential diagnosis and evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(6):1313–1320.

- Habermann TM, Steensma DP. Lymphadenopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75(7):723–732.

- Shipchandler TZ, Lorenz RR, McMahon J, Tubbs R. Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy due to silicone breast implants. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(8):830–832.

- Pangalis GA, Vassilakopoulos TP, Boussiotis VA, Fessas P. Clinical approach to lymphadenopathy. Semin Oncol. 1993;20(6):570–582.

- Salzman BE, Lamb K, Olszewski RF, Tully A, Studdiford J. Diagnosing cancer in the symptomatic patient. Prim Care. 2009;36(4):651–670.

- Rajasekaran K, Krakovitz P. Enlarged neck lymph nodes in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60(4):923–936.

- Dorfman T, Neymark M, Begal J, Kluger Y. Surgical Biopsy of Pathologically Enlarged Lymph Nodes: A Reappraisal. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2018 Nov;20(11):674-678.

- American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria: neck mass/adenopathy. https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69504/Narrative

- Dudea SM, Lenghel M, Botar-Jid C, Vasilescu D, Duma M. Ultrasonography of superficial lymph nodes: benign vs. malignant. Med Ultrason. 2012;14(4):294–306.

- Meier JD, Grimmer JF. Evaluation and management of neck masses in children. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(5):353–358.

- Monaco SE, Khalbuss WE, Pantanowitz L. Benign non-infectious causes of lymphadenopathy: a review of cytomorphology and differential diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40(10):925–938.

- Lioe TF, Elliott H, Allen DC, Spence RA. The role of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in the investigation of superficial lymphadenopathy; uses and limitations of the technique. Cytopathology. 1999;10(5):291–297.

- Thomas JO, Adeyi D, Amanguno H. Fine-needle aspiration in the management of peripheral lymphadenopathy in a developing country. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;21(3):159–162.

- Metzgeroth G, Schneider S, Walz C, et al. Fine needle aspiration and core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of lymphadenopathy of unknown aetiology. Ann Hematol. 2012;91(9):1477–1484.

- Karadeniz C, Oguz A, Ezer U, Oztürk G, Dursun A. The etiology of peripheral lymphadenopathy in children. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;16(6):525–531.