Bankart lesion

Bankart lesion is a tear or avulsion of the anteroinferior glenoid labrum rim below the middle of the glenoid socket that also involves the inferior glenohumeral ligament with or without the addition of avulsed bone fragment (bony Bankart) 1. Bankart lesion can either be purely cartilaginous or may involve the underlying bone also. Soft Bankart lesions or classic Bankart lesions involving the anteroinferior glenoid labrum are more common. Tears of the glenoid rim or Bankart lesion often occur with other shoulder injuries, such as an anterior dislocated shoulder (full or partial dislocation). Bankart lesions are frequently seen in association with a Hill-Sachs lesion (posterolateral humeral head compression fracture) 2.

Strictly speaking, a “Bankart lesion” refers to an injury of the glenoid labrum and associated glenohumeral capsule/ligaments. Injury to these reinforcing soft tissue structures is thought to predispose to recurrent dislocation 3.

The term “bony Bankart” (contrasted with a “soft Bankart” or “fibrous Bankart”) is often used to refer to fracture of the adjacent anteroinferior glenoid, an injury which also commonly occurs in the setting of anterior glenohumeral dislocation. Structurally, this fracture is thought to be less contributory to anterior instability.

Bankart lesion is named after Arthur Sydney Blundell Bankart (1879–1951) 4, a British orthopedic surgeon. In his original paper, Bankart described avulsive injury of the fibrocartilaginous soft tissues along the anteroinferior glenohumeral joint occurring in association with anterior shoulder dislocation. Although he acknowledged the frequent co-occurrence of glenoid and humeral fracture with these injuries, Bankart posited that it was injury to the soft tissue structures which specifically predisposed to recurrent dislocation 3. For this reason, some insist that the term “Bankart lesion” be reserved for soft tissue injury.

Bankart lesion variants

Many pathological Bankart lesion variants have been described in patients with recurrent instability, including a torn labrum with a medially stripped, but intact periosteal sleeve.

- Perthes lesion of the shoulder: Perthes lesion is a variant of Bankart lesion where there is a tear of the glenoid labrum, but with an intact scapular periosteum [Figure 3] 5. There is only minimal displacement of the torn anterior labrum, and hence the lesions are difficult to diagnose on routine MRI or MRA. MRA with arm in abduction and external rotation (ABER) stretches the anteroinferior joint capsule and inferior glenohumeral ligament and helps in better delineation of the lesion 6. It is important to detect this on MRA as it can be missed on arthroscopy because of the minimal displacement.

- Anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion (ALPSA): ALPSA lesion or anterior labrum periosteal sleeve avulsion was first defined by Neviaser et al. 7 as avulsion and medial rolling of the inferior labro-ligamentous complex along the scapular neck [Figure 4]. This is an important diagnosis to make as the lesion can be easily missed on arthroscopy 8. An ALPSA lesion (anterior labrum periosteal sleeve avulsion), during an operative procedure, needs to be converted to a Bankart lesion (reapposition of the medially rolled labrum to the glenoid rim) followed by a Bankart repair 5. The procedure needs relatively more expertise and more operating time. Preoperative knowledge of the severity of the lesion is useful for the operating surgeon.

Perthes lesion and ALPSA-lesion and chondral defects may be difficult to detect. A Perthes lesion may resemble a normal labrum, especially when no contrast is used. An ALPSA-lesion may be mistaken for a blob-like, thickened labrum and type II or III capsular attachment with a medially anchored capsule. As both types of lesion are associated with instability and recurrent dislocation, they are important to recognize. The use of intraarticular contrast is mandatory not to miss these entities. Although not routinely used, two specific positions of the arm that increase the width of a tear have been described. Traction on the labrum and inferior glenohumeral ligament in the ABER position (abduction of at least 90° with external rotation) increases the accuracy of MRA in case of an anteroinferior labral tear with minimal displacement. For an ALPSA-lesion, the FADIR position (full adduction with internal rotation) has been reported to help detection 9.

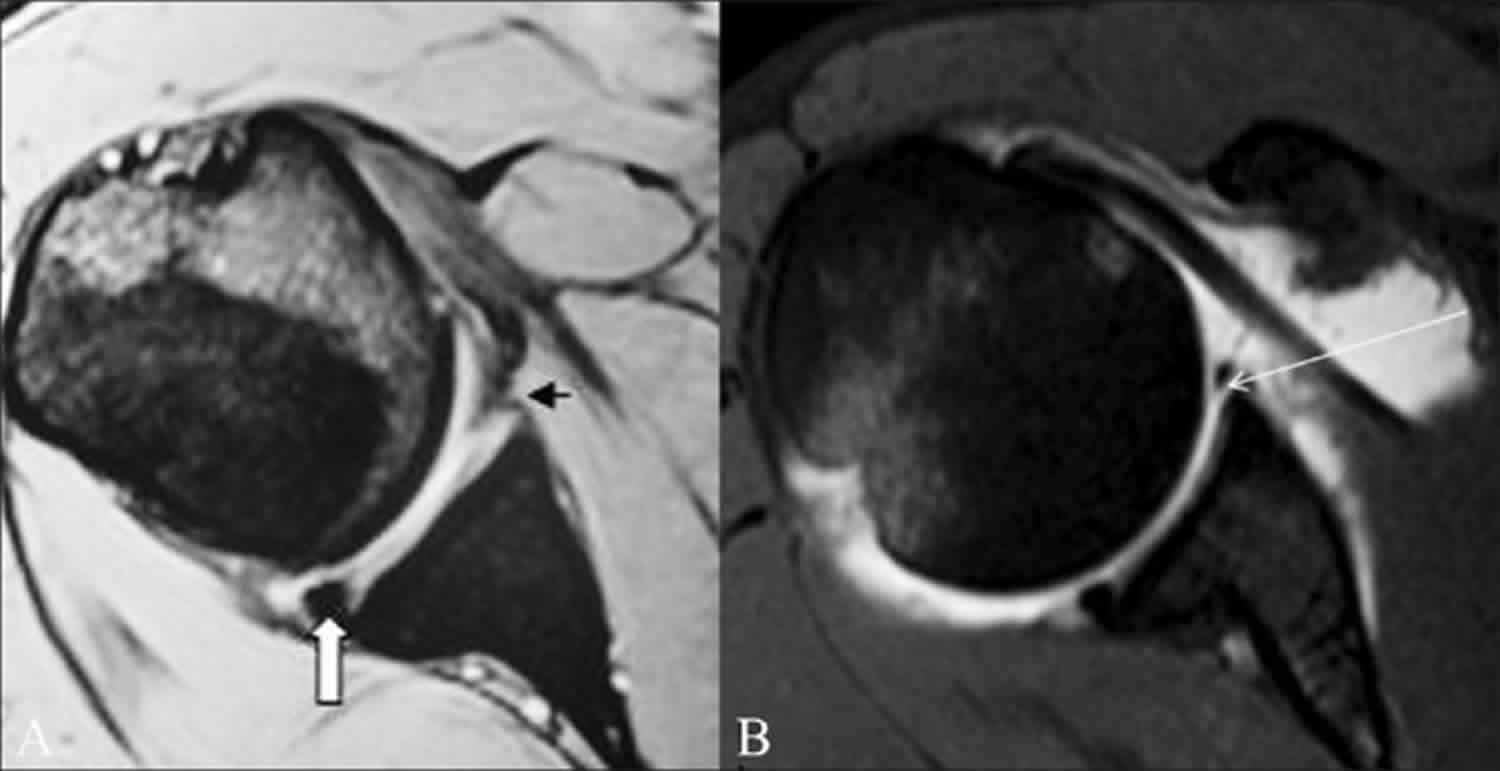

Figure 1. Classic Bankart lesion

Footnote: A 36-year-old male presented with recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation. (A) Conventional axial GRE MEDIC (multiecho data image combination) T2W MRI image shows an attenuated anteroinferior labrum (small arrow). The posterior labrum appears intact and is triangular in shape (thick arrow). Fast or turbo spin echo (FSE/TSE) T1W fat-saturated axial MRA image (B) shows a classic Bankart lesion as intercalation of contrast material (long arrow) beneath the hypointense anteroinferior labrum.

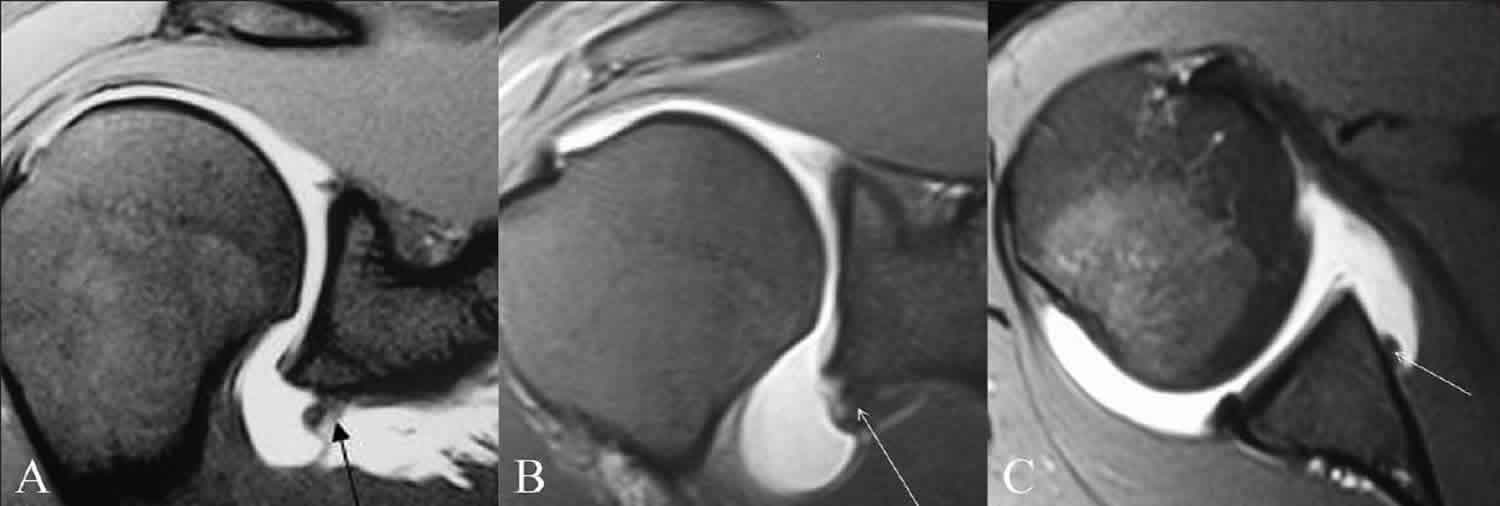

[Source 5 ]Figure 2. Bony Bankart lesion

Footnote: Bony Bankart lesion in a 28-year-old male with recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation. Axial TSE T1W fat-saturated MRA image (A) shows an absent anteroinferior labrum with bony injury (arrow). (B) Sagittal TSE T1W fat-saturated MRA and sagittal MRA image (C) 5 mm medial to B, show the full extent of the bony Bankart lesion (arrow).

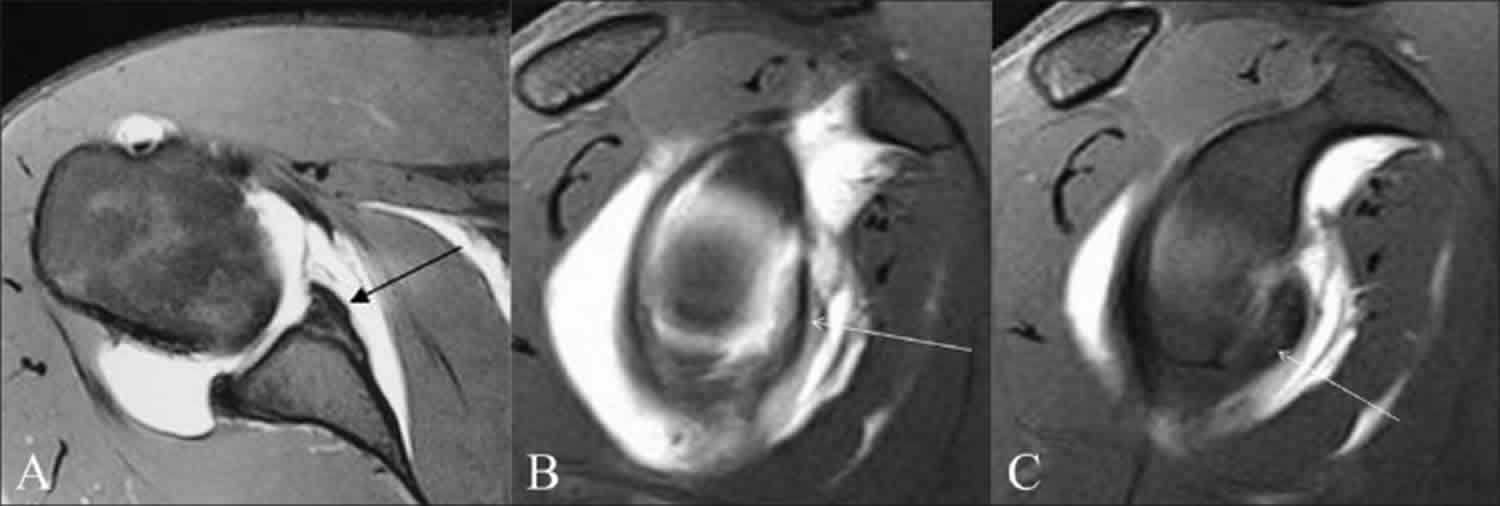

[Source 5 ]Figure 3. Perthes lesion of the shoulder

Footnote: A 16-year-old male presented with post-traumatic recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation. TSE T1W fat-saturated axial MRA image (A) and TSE T1W fat-saturated oblique axial MRA image with arm in ABER position (B) show intercalation of intra-articular contrast beneath the anterior labrum (small arrow) with an intact scapular periosteum (long arrow); this suggests a diagnosis of Perthes lesion. TSE T1W fat-saturated oblique sagittal MRA image (C) shows the extent of the lesion (arrows)

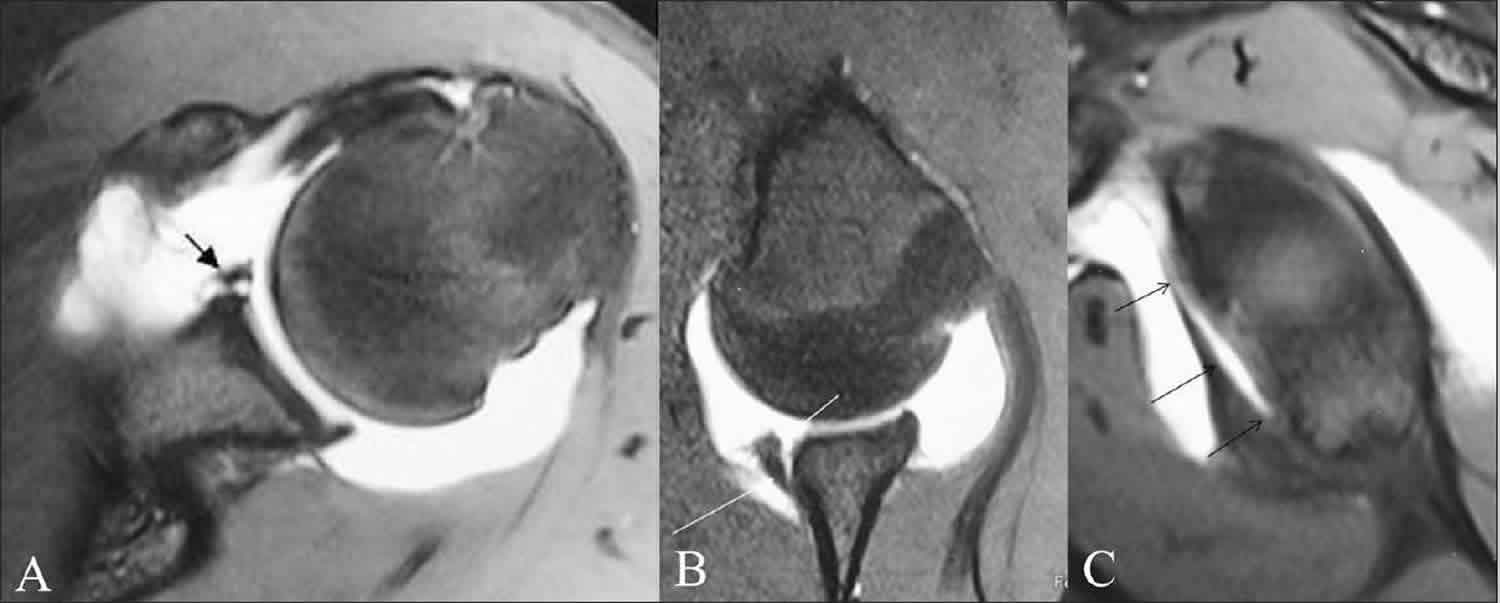

[Source 5 ]Figure 4. Anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion (ALPSA)

Footnote: Anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion (ALPSA) lesion in three different patients with anterior shoulder instability. TSE T1W fat-saturated coronal MRA images (A,B) and axial MRA image (C) show the anteroinferior labrum and antero-inferior glenohumeral ligament rolled back medially along the scapular neck (arrow).

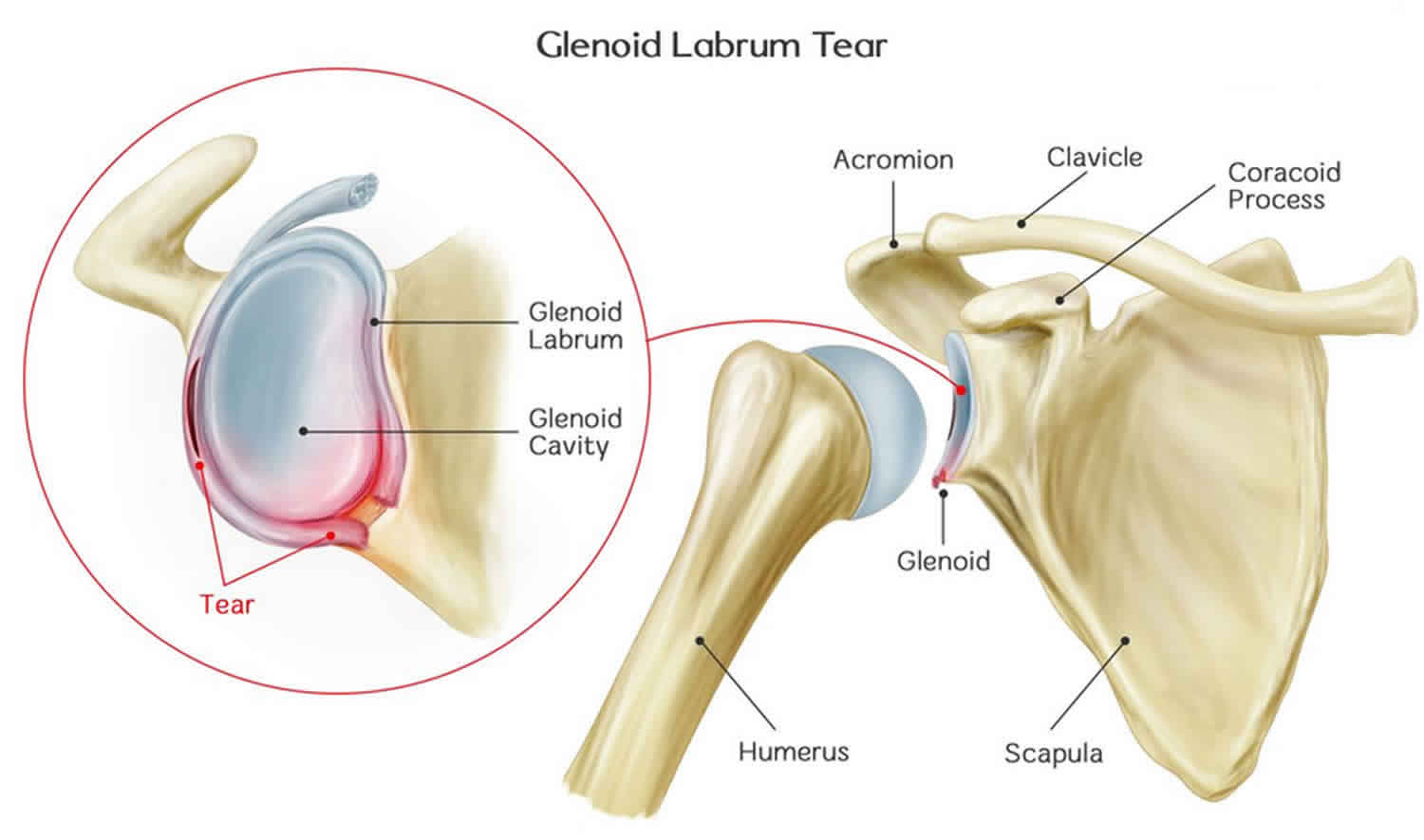

[Source 5 ]Shoulder joint anatomy

Your shoulder is a complex joint that is capable of more motion than any other joint in your body. It is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle).

Your arm is kept in your shoulder socket by your rotator cuff. These muscles and tendons form a covering around the head of your upper arm bone and attach it to your shoulder blade.

There is a lubricating sac called a bursa between the rotator cuff and the bone on top of your shoulder (acromion). The bursa allows the rotator cuff tendons to glide freely when you move your arm.

The shoulder region includes the glenohumeral joint, the acromioclavicular joint, the sternoclavicular joint and the scapulothoracic articulation (Figure 5). The glenohumeral joint capsule consists of a fibrous capsule, ligaments and the glenoid labrum. Because of its lack of bony stability, the glenohumeral joint is the most commonly dislocated major joint in the body. Glenohumeral stability is due to a combination of ligamentous and capsular constraints, surrounding musculature and the glenoid labrum. Static joint stability is provided by the joint surfaces and the capsulolabral complex, and dynamic stability by the rotator cuff muscles and the scapular rotators (trapezius, serratus anterior, rhomboids and levator scapulae).

Scapular stability collectively involves the trapezius, serratus anterior and rhomboid muscles. The levator scapular and upper trapezius muscles support posture; the trapezius and the serratus anterior muscles help rotate the scapula upward, and the trapezius and the rhomboids aid scapular retraction.

Ball and socket. The head of your upper arm bone fits into a rounded socket in your shoulder blade. This socket is called the glenoid. A slippery tissue called articular cartilage covers the surface of the ball and the socket. It creates a smooth, frictionless surface that helps the bones glide easily across each other.

The labrum

The glenoid is ringed by strong fibrous cartilage called the labrum. The labrum forms a gasket around the socket, adds stability, and cushions the joint. Thanks to the glenoid labrum rim, the socket deepens by as much as 50 percent, which allows the head of the upper arm to fit into position better. It also serves as an attachment for a number of different ligaments. The labrum is joined with the origin of the long tendon of the biceps superiorly and that of the triceps inferiorly. Usually, the labrum is in continuity with the articular cartilage as well as the glenohumeral ligaments 9.

For most of its circumference, the labrum commonly is triangular (anterior 45%, posterior 73%) or round (anterior 19%, posterior 12%) in shape 9. However, infrequent variations of the anterior labrum include a cleaved or notched appearance, flattening or even absence. When seen posteriorly, this is suggestive of a tear. A notched labrum is often associated with redundant anterior or posterior capsule or may be due to folding of the middle and inferior glenohumeral ligaments due to internal rotation of the humerus. In contrast, external rotation may result in a more flat labrum. A thinner or even absent labrum may be an age-related degenerative change, but can also be associated with instability 10.

Shoulder capsule. The joint is surrounded by bands of tissue called ligaments. They form a capsule that holds the joint together. The undersurface of the capsule is lined by a thin membrane called the synovium. It produces synovial fluid that lubricates the shoulder joint.

Rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is composed of four muscles: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis. Four tendons surround the shoulder capsule and help keep your arm bone centered in your shoulder socket. This thick tendon material is called the rotator cuff. The cuff covers the head of the humerus and attaches it to your shoulder blade. The subscapularis facilitates internal rotation, and the infraspinatus and teres minor muscles assist in external rotation. The rotator cuff muscles depress the humeral head against the glenoid. With a poorly functioning (torn) rotator cuff, the humeral head can migrate upward within the joint because of an opposed action of the deltoid muscle.

Bursa. There is a lubricating sac called a bursa between the rotator cuff and the bone on top of your shoulder (acromion). The bursa helps the rotator cuff tendons glide smoothly when you move your arm.

Figure 5. Shoulder anatomy

Bankart lesion causes

Bankart lesions occur as a direct result of anterior dislocation of the humeral head, whereby the humerus is compressed against the labrum. There is detachment of the anteroinferior labrum from the underlying glenoid, and the labral tear may further extend further superiorly or posteriorly. Impaction fracture of the anteroinferior glenoid margin commonly co-occurs. “Soft” Bankart lesions are more common than “bony” Bankart lesions 2. The same mechanism of compression can result in a Hill-Sachs lesion. Bankart and Hill-Sachs lesions are 11x more likely to occur together than isolated injuries 2.

Bankart lesions are frequently the results of collisions, accidents, and sports injuries (either acute injuries or overuse injuries from repetitive arm motions). Though anyone can sustain this injury, young men in their twenties are most susceptible.

Possible causes of shoulder dislocations and lesions:

- Falling on an outstretched arm

- A direct blow to the shoulder

- A sudden pull, such as when trying to lift a heavy object

- A violent overhead reach, such as when trying to stop a fall or slide

- Car accidents. A sudden blow to the shoulder can knock the ball from its socket, tearing the labrum.

- Sports collisions. Crashing into another person with speed and force — for example, during a football or hockey tackle — can shove the shoulder out of alignment or drag the arm forward or backward, leading to dislocations.

- Falls from sports. Falling and landing on one’s shoulder can lead to shoulder dislocations in athletes, especially in sports where falling with height or speed is common, like gymnastics, skating, rollerblading, or skiing. Sliding into bases during softball or baseball can also harm the shoulder.

- Falls not from sports. Falling off a ladder or tripping on a crack in the sidewalk can deliver enough force to dislocate the shoulder. Elderly people and those with gait problems can be highly susceptible to these types of falls.

- Overuse injuries. In some athletes, overuse of the shoulder can lead to loose ligaments and instability. Swimmers, tennis players, volleyball players, baseball pitchers, gymnasts, and weight lifters are prone to this problem. In addition, non-athletes may develop instability from repeated overhead motions of the arm (for example, swinging a hammer).

- Loose ligaments. Some people have a genetic predisposition to loose ligaments throughout the body (e.g., double-jointed individuals). They may find that their shoulders pop out of alignment easily.

- Physical abuse. Domestic violence, physical bullying, or fighting can involve falls, blows, or sudden wrenching movements that may pull the ball from the socket, damaging surrounding tissue.

Bankart lesion symptoms

Bankart lesion symptoms are very similar to those of other shoulder injuries. A thorough doctor’s exam is necessary to properly diagnose your symptoms.

Symptoms of a Bankart lesion can include:

- Pain. When reaching overhead or with overhead activities, at night, or with daily activities. Throwing a ball may also cause pain.

- A sense of instability in the shoulder

- Shoulder dislocations

- Catching, locking, popping, or grinding

- Occasional night pain or pain with daily activities

- Decreased range of motion

- Loss of strength

- Instability and weakness. The shoulder may “just hang there,” pop out of the joint, or feel too loose.

- Limited range of motion. Sudden difficulty moving the shoulder in any direction may indicate a tear.

- Unusual noises or sensations in the shoulder. Grinding, catching (not moving fluidly), locking in place, or popping can all be symptoms of torn tissue getting caught in the joint.

Bankart lesion diagnosis

If you are experiencing shoulder pain or your shoulder continues to dislocate or feel unstable, see a doctor to diagnose a Bankart lesion. Your doctor will take a history of your injury. You may be able to remember a specific incident or you may note that the pain gradually increased. Your doctor will do several physical tests to check range of motion, stability, and pain. In addition, your doctor will request x-rays and an MRI to see if there are any other reasons for your problems.

Because the rim of the shoulder socket is soft tissue, x-rays will not show damage to it. Your doctor may order a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. In both instances, a contrast medium may be injected to help detect tears. Ultimately, however, the diagnosis will be made with arthroscopic surgery.

Bankart lesion treatment

Bankart lesions do heal, and therefore early surgical intervention (if any) is not required. In Bankart repairs, the labral fragment is sutured back to the glenoid rim using suture anchors.

Medical therapy

- Anti-inflammatory medication: Until the doctor is able to determine a final diagnosis, you might be given a prescription of anti-inflammatory medications to help relieve symptoms.

- Rest: Instead of trying to move the shoulder all around, you need to give it time to rest and relax. Stop trying to play sport with it, and simply follow the rehabilitation advice from your therapist.

- Rehabilitation exercises: Rehabilitation exercises in the early stages work to mobilize the shoulder and to reduce inflammation. Later, they can also help to strengthen the rotator cuff muscles. When the muscles are strengthened, they can help to withstand more of an impact or injury that comes along.

If these nonsurgical measures are insufficient, your doctor may recommend surgery. Depending upon your injury, your doctor may perform a traditional, open procedure, or an arthroscopic procedure in which small incisions and miniature instruments are used.

Bankart repair

In Bankart repair, the labral fragment is sutured back to the glenoid rim using suture anchors. Preoperative imaging can delineate the exact extent of the injury in these cases, thereby providing an estimate of the severity of the injury and the level of difficulty to be anticipated by the operating surgeon and also the number of anchors to be used in the procedures.

Bony Bankart lesions are treated by bony Bankart repair or “bony Bankart bridge procedure.” Preoperative imaging can help delineate the extent of bone loss and can be done using CT scan but is also well documented with MRI. MRI has the added advantage of being able to detect the labrocapsular and tendinous pathologies as well.

Chronic bony Bankart lesions with resorption of the detached fragment may need bone grafting and therefore exact assessment of the bony fragment is important.

Risks of Bankart repair surgery

The risks of surgery for shoulder instability include but are not limited to the following:

- infection

- injury to nerves and blood vessels

- inability to carry out the planned repair

- stiffness of the joint

- tear of the rotator cuff

- pain

- persistent instability

- the need for additional surgeries

There are also risks associated with anesthesia including death. An experienced shoulder surgery team will use special techniques to minimize these risks but cannot totally eliminate them.

Rehabilitation

- After your surgery is complete, you want to keep your shoulder in a sling for around three to six weeks on average, depending on your doctor’s recommendation.

- Your doctor will also prescribe gentle, passive, pain-free range-of-motion exercises. Gentle range-of-motion exercises are beneficial after going through surgery and can prevent frozen shoulder.

- Once the sling is removed, you need to perform flexibility and motion exercises more actively.

- After range of motion has been achieved, the stability and strengthening phase can proceed.

- Athletes are often able to begin partaking in any sport-specific exercises 12 weeks after the surgery, but it will take four to six months for the shoulder to heal fully.

- Waldt S, Burkart A, Imhoff AB, Bruegel M, Rummeny EJ, Woertler K. Anterior shoulder instability: Accuracy of MR arthrography in the classification of anterior labroligamentous injuries. Radiol. 2005;237:578–83.

- Horst K, Von Harten R, Weber C et-al. Assessment of coincidence and defect sizes in Bankart and Hill-Sachs lesions after anterior shoulder dislocation: a radiological study. Br J Radiol. 2004;87 (915): 20130673. doi:10.1259/bjr.20130673

- Bankart ASB. Recurrent or Habitual Dislocation of the Shoulder-Joint. (1923) Br Med J;2:1132 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.3285.1132

- Somford MP, Nieuwe Weme RA, van Dijk CN, IJpma FF, Eygendaal D. Are eponyms used correctly or not? A literature review with a focus on shoulder and elbow surgery. (2016) Evidence-based medicine. 21 (5): 163-71. doi:10.1136/ebmed-2016-110453

- Jana M, Srivastava DN, Sharma R, et al. Spectrum of magnetic resonance imaging findings in clinical glenohumeral instability. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2011;21(2):98–106. doi:10.4103/0971-3026.82284 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3137866

- Wischer TK, Bredella MA, Genant HK, Stoller DW, Bost FW, Tirman PF. Perthes lesion (a variant of the Bankart lesion): MR imaging and MR arthrographic findings with surgical correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:233–7.

- Neviaser TJ. The anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion lesion: A cause of anterior instability of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:17–21.

- Rowan KR, Keogh C, Andrews G, Cheong Y, Forster BB. Essentials of shoulder MR arthrography: A practical guide for the general radiologist. Clin Radiol. 2004;59:327–34.

- Pouliart N, Doering S, Shahabpour M. What can the Radiologist do to Help the Surgeon Manage Shoulder Instability?. J Belg Soc Radiol. 2016;100(1):105. Published 2016 Nov 19. doi:10.5334/jbr-btr.1227 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6100640

- Al-Riyami AM, Lim BK, Peh WC. Variants and pitfalls in MR imaging of shoulder injuries. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2014;18(1):36–44. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365833