Vestibular neuritis

Vestibular neuritis also known as labyrinthitis or vestibulitis, is an inflammation of the balancing center in your inner ear (or labyrinth) or the vestibulocochlear nerve connecting the inner ear to the brain. This inflammation disrupts the transmission of sensory information from the ear to the brain. Symptoms include hearing loss, a spinning sensation (vertigo), dizziness, difficulties with balance, vision, or hearing may result. Vestibular neuritis is usually caused by an infection. Infections of the inner ear are usually viral; less commonly, the cause is bacterial. Such inner ear infections are not the same as middle ear infections, which are the type of bacterial infections common in childhood affecting the area around the eardrum. Vestibular neuritis can occur in people of all ages, but is rarely reported in children. Most people feel better within a few weeks (approximately three weeks), although it can take longer.

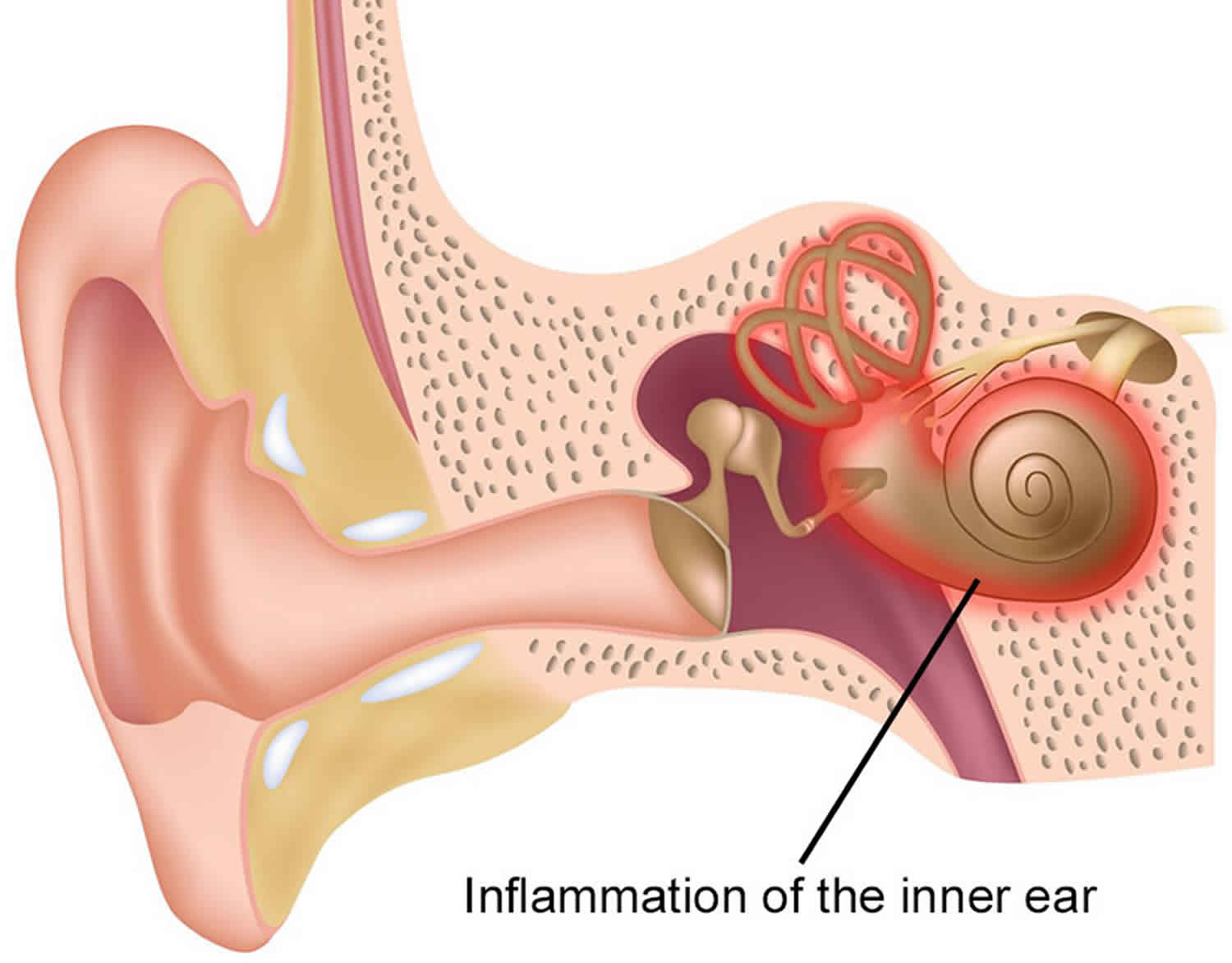

The vestibule is a part of the inner ear that contains organs controlling balance. It is connected to the brain by the vestibular nerve (see Figures 1 and 2 below). Vestibular neuronitis is probably caused by a virus.

Vestibular neuronitis (inflammation of the vestibulocochlear nerve) affects the branch associated with balance, resulting in dizziness or vertigo but no change in hearing. The term neuronitis (damage to the sensory neurons of the vestibular ganglion) is also used. Vestibulocochlear nerve or 8th cranial nerve (CN VIII) sends balance and head position information from the inner ear to the brain. When this nerve becomes swollen (inflamed), it disrupts the way the information would normally be interpreted by the brain.

Labyrinthitis (inflammation of the labyrinth) occurs when an infection affects both branches of the vestibulo-cochlear nerve, resulting in hearing changes as well as dizziness or vertigo.

What do the symptoms of vestibular neuritis/labyrinthitis feel like?

Symptoms of vestibular neuritis are characterised by a sudden onset of a constant, intense spinning sensation that is usually disabling and requires bed rest. It is often associated with nausea, vomiting, unsteadiness, imbalance, difficulty with vision and the inability to concentrate.

While neuritis affects only the inner ear balance apparatus, labyrinthitis also affects the inner ear hearing apparatus and/or the cochlear nerve, which transmits hearing information. This means that labyrinthitis can cause hearing loss or ringing in the ears (tinnitus)

Can vestibular neuritis recur?

In most patients (95 percent and greater) vestibular neuritis is a one-time experience. Most patients fully recover.

Inner ear anatomy

The inner ear consists of a system of fluid-filled tubes and sacs called the labyrinth. The labyrinth serves two functions: hearing and balance.

The hearing function involves the cochlea, a snail-shaped tube filled with fluid and sensitive nerve endings that transmit sound signals to the brain.

The balance function involves the vestibular organs. Fluid and hair cells in the three loop-shaped semicircular canals and the sac-shaped utricle and saccule provide the brain with information about head movement.

Signals travel from the labyrinth to the brain via the vestibulo-cochlear nerve (the eighth cranial nerve), which has two branches. One branch (the cochlear nerve) transmits messages from the hearing organ, while the other (the vestibular nerve) transmits messages from the balance organs.

The brain integrates balance signals sent through the vestibular nerve from the right ear and the left ear. When one side is infected, it sends faulty signals. The brain thus receives mismatched information, resulting in dizziness or vertigo.

Figure 1. Inner ear anatomy

Figure 2. Parts of the inner ear

Vestibular neuritis causes

Researchers think the most likely cause of vestibular neuritis is a viral infection of the inner ear, swelling around the vestibulocochlear nerve (caused by a virus), or a viral infection that has occurred somewhere else in the body. Some examples of viral infections in other areas of the body include herpes virus (causes cold sores, shingles, chickenpox), measles, flu, mumps, hepatitis and polio. Genital herpes is not a cause of vestibular neuritis.

Although the symptoms of bacterial and viral infections may be similar, the treatments are very different, so proper diagnosis by a physician is essential.

Viral infection

Viral infections of the inner ear are more common than bacterial infections, but less is known about them. An inner ear viral infection may be the result of a systemic viral illness (one affecting the rest of the body, such as infectious mononucleosis, herpes virus, measles, flu, mumps, hepatitis and polio); or, the infection may be confined to the labyrinth or the vestibulo-cochlear nerve. Usually, only one ear is affected.

Some of the viruses that have been associated with vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis include herpes viruses (such as the ones that cause cold sores or chicken pox and shingles), influenza, measles, rubella, mumps, polio, hepatitis, and Epstein-Barr. Other viruses may be involved that are as yet unidentified because of difficulties in sampling the labyrinth without destroying it. Because the inner ear infection is usually caused by a virus, it can run its course and then go dormant in the nerve only to flare up again at any time. There is currently no way to predict whether or not it will come back.

Bacterial infection

In serous labyrinthitis, bacteria that have infected the middle ear or the bone surrounding the inner ear produce toxins that invade the inner ear via the oval or round windows and inflame the cochlea, the vestibular system, or both. Serous labyrinthitis is most frequently a result of chronic, untreated middle ear infections (chronic otitis media) and is characterized by subtle or mild symptoms.

Less common is suppurative labyrinthitis, in which bacterial organisms themselves invade the labyrinth. The infection originates either in the middle ear or in the cerebrospinal fluid, as a result of bacterial meningitis. Bacteria can enter the inner ear through the cochlear aqueduct or internal auditory canal, or through a fistula (abnormal opening) in the horizontal semicircular canal.

Vestibular neuritis pathophysiology

Vestibular neuritis is believed to be an inflammatory disorder selectively affecting the vestibular portion of the 8th cranial nerve. The cause is presumed to be of viral origin (e.g., the reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus infection), but other causes of vascular etiology and immunologic in origin are proposals. Vestibular damage appears to have a predilection for the superior portion of the vestibular labyrinth (supplied by the superior division of the vestibular nerve) over the inferior aspect of the vestibular labyrinth (supplied by the inferior portion of the vestibular nerve). The underlying mechanism is unclear, but this phenomenon may be explainable by anatomical differences between the two vestibular divisions 1.

Vestibular neuritis symptoms

Symptoms of viral neuritis can be mild or severe, ranging from subtle dizziness to a violent spinning sensation (vertigo). They can also include nausea, vomiting, unsteadiness and imbalance, difficulty with vision, and impaired concentration.

Sometimes the symptoms can be so severe that they affect the ability to stand up or walk. Viral labyrinthitis may produce the same symptoms, along with tinnitus (ringing or noises in the ear) and/or hearing loss.

Vestibular neuritis symptoms include:

- Sudden, severe vertigo (spinning/swaying sensation)

- Dizziness

- Balance difficulties

- Nausea, vomiting

- Concentration difficulties

Vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis are closely related disorders. Vestibular neuritis involves swelling of a branch of the vestibulocochlear nerve (the vestibular portion) that affects balance. Labyrinthitis involves the swelling of both branches of the vestibulocochlear nerve (the vestibular portion and the cochlear portion) that affects balance and hearing. The symptoms of labyrinthitis are the same as vestibular neuritis plus the additional symptoms of tinnitus (ringing in the ears) and/or hearing loss.

Generally, the most severe symptoms (severe vertigo and dizziness) only last a couple of days, but while present, make it extremely difficult to perform routine activities of daily living. After the severe symptoms lessen, most patients make a slow, but full recovery over the next several weeks (approximately three weeks). However, some patients can experience balance and dizziness problems that can last for several months.

The symptoms in vestibular neuritis are typically constant, in contrast to the episodic symptoms of other peripheral causes such as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) or Meniere’s disease. Symptoms are worsened with head movement but not triggered. Symptoms generally develop over several hours, peak within the first 24 to 48 hours, and typically last several days before resolving without intervention. Patients will likely note a preceding or concurrent viral illness, but it is important to note that the lack of this history does not rule out the disease as it is reported to be absent in up to 50% of patients 2.

Other symptoms, such as headaches, are usually absent. It is vital to ask the patient about accompanying symptoms that may suggest central disorders of vertigo, such as visual changes, somatosensory changes, weakness, dysarthria, incoordination, or an inability to walk. If any of these are present, one must broaden the differential with to central causes of vertigo. When the additional symptom of unilateral hearing loss is present, this shifts the diagnosis towards labyrinthitis 2. When attempting to differentiate this associated hearing change from Meniere disease, it is important to know that Meniere disease also presents with vestibular and auditory dysfunction. Still, patients with Meniere have more episodic and not continuous symptoms lasting 20 minutes to usually no more than 12 hours 1.

Acute vestibular neuritis

Onset of symptoms is usually very sudden, with severe dizziness developing abruptly during routine daily activities. In other cases, the symptoms are present upon awakening in the morning. The sudden onset of such symptoms can be very frightening; many people go to the emergency room or visit their physician on the same day.

Chronic vestibular neuritis

After a period of gradual recovery that may last several weeks, some people are completely free of symptoms. Others have chronic dizziness if the virus has damaged the vestibular nerve.

Many people with chronic neuritis or labyrinthitis have difficulty describing their symptoms, and often become frustrated because although they may look healthy, they don’t feel well. Without necessarily understanding the reason, they may observe that everyday activities are fatiguing or uncomfortable, such as walking around in a store, using a computer, being in a crowd, standing in the shower with their eyes closed, or turning their head to converse with another person at the dinner table.

Some people find it difficult to work because of a persistent feeling of disorientation or “haziness,” as well as difficulty with concentration and thinking.

Vestibular neuritis complications

Two important complications associated with vestibular neuritis are benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) and persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD), a relatively new term. Research has found that 10 to 15% of patients with vestibular neuritis will develop BPPV in the affected ear within a few weeks 3. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness is a new diagnostic syndrome of non-spinning vertigo and unsteadiness, which combines significant features of chronic subjective dizziness, phobic postural vertigo, and other related disorders 4. One study found persistent postural-perceptual dizziness in 25% of patients who were followed 3 to 12 months after acute or episodic vestibular disorders 5.

Vestibular neuritis diagnosis

No specific tests exist to diagnose vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis. Therefore, a process of elimination is often necessary to diagnose the condition. Because the symptoms of an inner ear virus often mimic other medical problems, a thorough examination is necessary to rule out other causes of dizziness, such as stroke, head injury, cardiovascular disease, allergies, side effects of prescription or nonprescription drugs (including alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, and many illegal drugs), neurological disorders, and anxiety.

In most patients, a diagnosis of vestibular neuritis can be made with an office visit to a vestibular specialist. These specialists include an otologist (ear doctor) or neurotologist (doctor who specializes in the nervous system related to the ear). Referral to an audiologist (hearing and vestibular [balance] clinician) may be made to perform tests to further evaluate hearing and vestibular damage. Tests to help determine if symptoms might be caused by vestibular neuritis include hearing tests, vestibular (balance) tests and a test to determine if a portion of the vestibulocochlear nerve has been damaged. Another specific test, called a head impulse test, examines how difficult it is to maintain focus on objects during rapid head movements 6. The presence of nystagmus, which is uncontrollable rapid eye movement, is a sign of vestibular neuritis.

If symptoms continue beyond a few weeks or become worse, other tests are performed to determine if other illnesses or diseases are causing the same symptoms. Some of these other possible health conditions include stroke, head injury, brain tumor, and migraine headache. To rule out some of the disorders of the brain, an MRI with dye (called a contrast agent) may be ordered.

Physical exam

Patients presenting with vestibular neuritis will have a normal physical exam and neurological exam. The clinician needs to look for clues that might point to a central cause of vertigo, warranting a more thorough evaluation. Central causes of vertigo are usually continuous symptoms along with truncal instability, an unsteady gait, dysarthria, and other focal neurological symptoms. Symptoms that are episodic in nature point to the more common other peripheral causes like benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) and Meniere’s disease. Other findings that are consistent with peripheral causes of vertigo, like vestibular neuritis, include a negative HINTs exam.

The HINTS examination consists of three components 7:

- Head Impulse,

- Nystagmus, and

- Test of Skew.

HINTs has been found to have high sensitivity and specificity (100% and 96%) for distinguishing peripheral from central vertigo in patients presenting with acute vestibular syndrome when performed correctly by the experienced clinician 8. Videos of HINTs exam are shown below. The following components make up HINTs exam are described as follows:

- The head impulse is performed with the patient sitting facing the examiner. Head positioning is at about 20 degrees to the left and right from midline, and then the examiner will briskly turn the head toward the midline. The examiner will then check to see whether or not the patient can maintain visual fixation on the examiner. If the patient’s eyes are not able to fixate on the examiner during the maneuver, their eyes will be noted to saccade back toward the midline. When the saccade is present, the test is considered a positive test and points towards a peripheral etiology such as vestibular neuritis. If there is a corrective saccade in both directions, this is worrisome for a central pathology. When the patient can fixate on the examiner’s nose during the entire maneuver, the test is considered negative and points towards a central etiology.

- Nystagmus is another exam tool that is a part of the HINTS exam. It is important to note that the naming of nystagmus is for the direction of the fast component. Nystagmus follows a rule termed Alexander’s law, which states that the intensity of nystagmus increases when the patient looks towards the direction of the fast phase. The slow phase of the nystagmus beats towards the injured side. Spontaneous nystagmus (when a patient is looking straight ahead without fixation) is determined to be negative (peripheral) if it is described as horizontal beating or horizontal-torsional and is unidirectional (fast phase beats towards one direction regardless of the orientation of gaze, patient looking left or right). Vertigo that is observed to be vertical and or bidirectional is considered a positive finding and points to a central etiology.

- The test of skew is performed with the patient facing the examiner. The examiner then covers and uncovers the patient’s eye one at a time with his hand while the patient attempts to fixate on the examiner. Any deviation of one eye while it is covered, followed by correction after uncovering the eye, is considered a positive or abnormal test pointing to a central etiology. The patient with vestibular neuritis should be able to maintain symmetrical eye alignment without deviation during the entire exam.

Other neurologic signs and symptoms: dysarthria, dysphagia, facial droop, dysmetria, motor weakness, sensory loss, and abnormal reflexes are typically absent 8. The auditory function in patients with vestibular neuritis is usually preserved, but when there is combined unilateral hearing loss, it is called labyrinthitis. It is crucial to assess the patient’s gait and posture as it can help localize the affected ear or be a signal of a more grave diagnosis. Their seated posture should be normal, and while their gait is usually unaffected, they will tend to veer or fall toward the affected side (opposite to nystagmus fast phase).

Vestibular neuritis treatment

When other illnesses have been ruled out and the symptoms have been attributed to vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis, treatment consists of managing the symptoms of vestibular neuritis, treating a virus (if suspected), and participating in a balance rehabilitation program 9.

Managing symptoms. When vestibular neuritis first develops, the focus of treatment is to reduce symptoms. Drugs to reduce nausea include ondansetron (Zofran®) and metoclopramide (Reglan®). If nausea and vomiting are severe and not able to be controlled with drugs, patients may be admitted to the hospital and given IV fluids to treat dehydration.

To reduce dizziness, drugs such as meclizine (Antivert®), diazepam (valium), phenergen (promethazine hydrochloride), compazine, benadryl (diphenhydramine) and lorazepam (Ativan®) are prescribed. The different types of drugs used to reduce dizziness are group together and called by the general name, vestibular suppressants. Vestibular suppressants should be used no longer than three days as these medications can delay central compensation and lead to chronic problems and recurrent vertigo and may make recovery more difficult 9.

Sometimes steroids (e.g., prednisone) are also used to reduce inflammation in your inner ear, but their efficacy remains controversial. This therapy was studied in a 2011 Cochrane review 10, which found insufficient evidence to recommend their use in those with acute vestibular dysfunction.

Treating a virus. If a herpes virus is thought to be the cause of the vestibular neuritis, antiviral medicine such as acyclovir or valacyclovir is used or antibiotics (e.g., amoxicillin) if a middle ear infection is present. Antibiotics are not used to treat vestibular neuritis because this disorder is not caused by bacteria. However, the use of valacyclovir either alone or combined with a glucocorticoid has not been shown to be effective 11.

If treated promptly, many inner ear infections cause no permanent damage. In some cases, however, permanent loss of hearing can result, ranging from barely detectable to total. Permanent damage to the vestibular system can also occur. Positional dizziness or BPPV (Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo) can also be a secondary type of dizziness that develops from neuritis or labyrinthitis and may recur on its own chronically. Labyrinthitis may also cause endolymphatic hydrops (abnormal fluctuations in the inner ear fluid called endolymph) to develop several years later.

Testing and treatment during the chronic phase

If symptoms persist, further testing may be appropriate to help determine whether a different vestibular disorder is in fact the correct diagnosis, as well as to identify the specific location of the problem within the vestibular system. These additional tests will usually include an audiogram (hearing test); and electronystagmography (ENG) or videonystagmography, which may include a caloric test to measure any differences between the function of the two sides. Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials may also be suggested to detect damage in a particular portion of the vestibular nerve.

Physicians and audiologists will review test results to determine whether permanent damage to hearing has occurred and whether hearing aids may be useful. They may also consider treatment for tinnitus if it is present.

If symptoms of dizziness or imbalance are chronic and persist for several months, vestibular rehabilitation exercises (a form of physical therapy) may be suggested in order to evaluate and retrain the brain’s ability to adjust to the vestibular imbalance. Usually, the brain can adapt to the altered signals resulting from labyrinthitis or neuritis in a process known as compensation. Vestibular rehabilitation exercises facilitate this compensation.

In order to develop effective retraining exercises, a physical therapist will assess how well the legs are sensing balance (that is, providing proprioceptive information), how well the sense of vision is used for orientation, and how well the inner ear functions in maintaining balance. The evaluation may also detect any abnormalities in the person’s perceived center of gravity. As part of assessing the individual’s balancing strategies, a test called computerized dynamic posturography is sometimes used.

After the evaluation, personalized vestibular rehabilitation exercises are developed. Most of these exercises can be performed independently at home, although the therapist will continue to monitor and modify the exercises. It is usually recommended that vestibular-suppressant medications be discontinued during this exercise therapy, because the drugs interfere with the ability of the brain to achieve compensation.

The exercises may provide relief immediately, but a noticeable difference may not occur for several weeks. Many people find they must continue the exercises for years in order to maintain optimum inner ear function, while others can stop doing the exercises altogether without experiencing any further problems. A key component of successful adaptation is a dedicated effort to keep moving, despite the symptoms of dizziness and imbalance. Sitting or lying with the head still, while more comfortable, can prolong or even prevent the process of adaptation.

Balance rehabilitation program

If balance and dizziness problems last longer than a few weeks, a vestibular physical therapy program may be recommended. The goal of this program is to retrain the brain to adapt to the changes in balance that a patient experiences.

As the first step in this program, a vestibular physical therapist evaluates the parts of the body that affect balance. These areas include:

- The legs (how well the legs “sense” balance – when attempting to stand or walk)

- The eyes (how well the sense of vision interprets the body’s position in relation to its surroundings)

- The ears (how well the inner ear functions to maintain balance)

- The body as a whole (how well the body interprets its center of gravity – does the body sway or have unsteady posture)

Based on the results of the evaluation, an exercise program is designed specifically for the patient.

Vestibular compensation

Vestibular compensation is a process that allows the brain to regain balance control and minimize dizziness symptoms when there is damage to, or an imbalance between, the right and left vestibular organs (balance organs) in the inner ear. Essentially, the brain copes with the disorientating signals coming from the inner ears by learning to rely more on alternative signals coming from the eyes, ankles, legs and neck to maintain balance.

Vestibular neuritis exercises

Please note that you should not attempt any of these exercises without first seeing a specialist or physiotherapist for a comprehensive assessment, advice and guidance. Your doctor can refer you. Some of these exercises will not be suitable for everyone, and some are only suitable for certain conditions.

The key to a successful balance rehabilitation program is to repeat the set of personalized exercises 2 to 3 times a day. By repeating these exercises, the brain learns how to adjust to the movements that cause dizziness and imbalance. Many of the exercises can be done at home, which will speed recovery. Vestibular rehabilitation specialists provide specific instructions on how to perform the exercises, identify which exercises can be done at home, and provide other home safety tips to prevent falls.

Some examples of balance exercises:

Overall body posture balance exercises

- Exercises that shift body weight forward and backward and from side-to-side while standing

Eye/ear head-turn exercises

- Focusing eyes on an object while turning head from side to side

- Keeping vision steady while making rapid side-to-center head turns

- Focusing eyes on a distant object, with brief glances at floor, while continuing to walk toward the object

Cawthorne-Cooksey exercises

The aims of the Cawthorne-Cooksey exercises include relaxing the neck and shoulder muscles, training the eyes to move independently of the head, practising good balance in everyday situations, practising the head movements that cause dizziness (to help the development of vestibular compensation), improving general co-ordination and encouraging natural unprompted movement.

You should be assessed for an individual exercise programme to ensure you are doing the appropriate exercises. You could ask if it is possible for a friend or relative to be with you at the assessment. It can be helpful if someone else learns the exercises and helps you with them.

You will be given guidance on how many repetitions of each exercise to do and when to progress to the next set of exercises. As a general rule, you should build up gradually from one set of exercises to the next, spending one to two minutes on each exercise. You might find that your dizziness problems get worse for a few days after you start the exercises, but you should persevere with them.

In order to pace your exercises, so you do not move on to exercises that are too difficult before you are ready, you may also like to try using a ‘number rating scale’. For example, 0 through to 5 for the severity of your symptoms (0 being no symptoms and 5 being severe symptoms). It would be advisable to start each exercise at a level that you would rate as a 2 or 3 on the rating scale (i.e. it provokes mild to moderate symptoms that disappear quickly after stopping the exercise). You would then only move on to the next exercise once the current exercise evoked a 0 on the scale, for three days in a row. Please be aware that it may take a few days for you to get used to the exercises. It may be advised not to undertake exercises that you would rate a 4 or 5 on the scale.

A diary such as the one below might help you to keep track of the exercises and help with knowing when to make each one harder.

Make sure that you are in a safe environment before you start any of the exercises to reduce the risk of injury. Do not complete any exercises if you feel that you are risk of falling without safety measures in place to stop this. It is also important to note that you may experience mild dizziness whilst doing these exercises. This is completely normal.

It is advised not to complete more than 10 of each of the exercises below. They should be completed slowly at first. As the exercise becomes easier over time you can start to do them more quickly.

The Cawthorne-Cooksey exercises might include the following:

1. In bed or sitting

- A. Eye movements

- Up and down

- From side to side

- Focusing on finger moving from three feet to one foot away from face

- B. Head movements

- Bending forwards and backwards

- Turning from side to side

2. Sitting

- A. Eye and head movements, as 1

- B. Shrug and circle shoulders

- C. Bend forward and pick up objects from the ground

- D. Bend side to side and pick up objects from the ground

3. Standing

- A. Eye, head and shoulder movements, as 1 and 2

- B. Change from a sitting to a standing position with eyes open, then closed (please note this is not advised for the elderly with postural hypertension)

- C. Throw a ball from hand to hand above eye level

- D. Throw a ball from hand to hand under the knee

- E. Change from a sitting to a standing position, turning around in between

4. Moving about

- A. Walk up and down a slope

- B. Walk up and down steps

- C. Throw and catch a ball

- D. Any game involving stooping, stretching and aiming (for example, bowling)

Gaze stabilization exercises

The aim of gaze stabilization exercises is to improve vision and the ability to focus on a stationary object while the head is moving.

Your therapist should assess you and say which exercises are suitable for you.

- Look straight ahead and focus on a letter (for example, an ‘E’) held at eye level in front of you.

- Turn your head from side to side, keeping your eyes focused on the target letter. Build up the speed of your head movement. It is crucial that the letter stays in focus. If you get too dizzy, slow down.

- Start doing the exercise for a length of time that brings on mild to moderate symptoms (you could use the number rating scale). This might only be for 10 seconds. Over time, you can build up to one minute (the brain needs this time in order to adapt). Build up gradually to repeat three to five times a day.

You can also do this exercise with an up and down (nodding) movement.

Progressions with this exercise can include placing the target letter on a busy background. You should start the exercise whilst seated and then move on to standing.

Living with damage caused by vestibular neuritis

If your treatment involves vestibular rehabilitation exercises, it is important to continue the exercises at home for as long as you are advised to by the specialist, balance physiotherapist. To speed up your adaption process, it is vital to keep moving, despite dizziness or imbalance, even though sitting or lying is more comfortable. The aim is to return to your previous activity, work or sport, which helps with the adaptation process, and allows the balance system to function normally.

Vestibular neuritis prognosis

The natural history of this disease is uncomplicated with complete resolution in most cases. Some can have incomplete resolution and with a study showing 15% with persistent symptoms at one year 2. Recurrence of vestibular neuritis is infrequent, with studies that have shown its recurrence in only 2 to 11% of patients 12.

References- Baloh RW. Clinical practice. Vestibular neuritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003 Mar 13;348(11):1027-32.

- Furman JM, Cass SP. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999 Nov 18;341(21):1590-6.

- Mandalà M, Santoro GP, Awrey J, Nuti D. Vestibular neuritis: recurrence and incidence of secondary benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010 May;130(5):565-7.

- Popkirov S, Staab JP, Stone J. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): a common, characteristic and treatable cause of chronic dizziness. Pract Neurol. 2018 Feb;18(1):5-13.

- Staab JP, Eckhardt-Henn A, Horii A, Jacob R, Strupp M, Brandt T, Bronstein A. Diagnostic criteria for persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): Consensus document of the committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society. J Vestib Res. 2017;27(4):191-208.

- Rosengren SM, Colebatch JG, Young AS, Govender S, Welgampola MS. Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in practice: Methods, pitfalls and clinical applications. Clin Neurophysiol Pract. 2019;4:47-68.

- Smith T, Rider J, Cen S, et al. Vestibular Neuronitis (Labyrinthitis) [Updated 2019 Dec 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549866

- Tarnutzer AA, Berkowitz AL, Robinson KA, Hsieh YH, Newman-Toker DE. Does my dizzy patient have a stroke? A systematic review of bedside diagnosis in acute vestibular syndrome. CMAJ. 2011 Jun 14;183(9):E571-92.

- Muncie HL, Sirmans SM, James E. Dizziness: Approach to Evaluation and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Feb 01;95(3):154-162.

- Fishman JM, Burgess C, Waddell A. Corticosteroids for the treatment of idiopathic acute vestibular dysfunction (vestibular neuritis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 May 11;(5):CD008607

- Vroomen P. Methylprednisolone, valacyclovir, or both for vestibular neuritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004 Nov 25;351(22):2344-5; author reply 2344-5.

- Kim YH, Kim KS, Kim KJ, Choi H, Choi JS, Hwang IK. Recurrence of vertigo in patients with vestibular neuritis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011 Nov;131(11):1172-7.