What is Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome

Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome is an extremely rare genetic disorder that affects the skin and lungs and increases the risk of certain types of tumors; non-cancerous (benign) skin tumors; lung cysts and/or history of pneumothorax (collapsed lung); and various types of renal tumors. Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome signs and symptoms vary among affected individuals. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is characterized by multiple noncancerous (benign) skin tumors (fibrofolliculomas, trichodiscomas/angiofibromas, perifollicular fibromas, and acrochordons), particularly on the face, neck, and upper chest 1. Fibrofolliculomas are a type of benign skin tumor specific to Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. These growths typically first appear in a person’s twenties or thirties and become larger and more numerous over with age. Most people with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome also have multiple cysts in both lungs (pulmonary cysts) that can be seen on high-resolution chest CT scan. Lung cysts are mostly bilateral and multifocal; most individuals are asymptomatic but they put people at increased risk for spontaneous pneumothorax. Additionally, Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is associated with an elevated risk of developing cancerous or noncancerous kidney tumors. Individuals with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome are at a sevenfold increased risk for renal tumors that are typically bilateral and multifocal and usually slow growing; median age of tumor diagnosis is 48 years. The most common renal tumors are a hybrid of oncocytoma and chromophobe histologic cell types (so-called oncocytic hybrid tumor) and chromophobe histologic cell types. Some families have renal tumor and/or autosomal dominant spontaneous pneumothorax without cutaneous manifestations. Other types of cancer have also been reported in affected individuals, but it is unclear whether these tumors are actually a feature of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome.

Patients with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome are at increased risk of developing renal tumors lifelong, with an average age of onset at 50 years 2. Lifelong renal surveillance should begin at the age of twenty. Some experts recommend initial MRI followed by annual MRI or ultrasound, while others suggest CT scans every 3 to 5 years. There is also a risk for pneumothoraces, which occur in 25% of patients during the third to sixth decades. Ninety percent of adult patients will show radiographic evidence of lung cysts. Patients should be counseled on pneumothorax symptoms and a high baseline resolution CT of the chest should be performed with follow-up scans every 3 to 5 years. There is no data to support the idea that patients with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome should be advised against air travel. However, they should be counseled on smoking cessation to prevent pneumothoraces. Additionally, a full-body skin examination at routine intervals to evaluate for suspicious pigmented lesions should be implemented since there may be an association between malignant melanoma and Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome.

Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome is caused by mutations in the FLCN gene. The condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion 2. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is extremely rare; its exact incidence is unknown. Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome has been reported in more than 400 families.

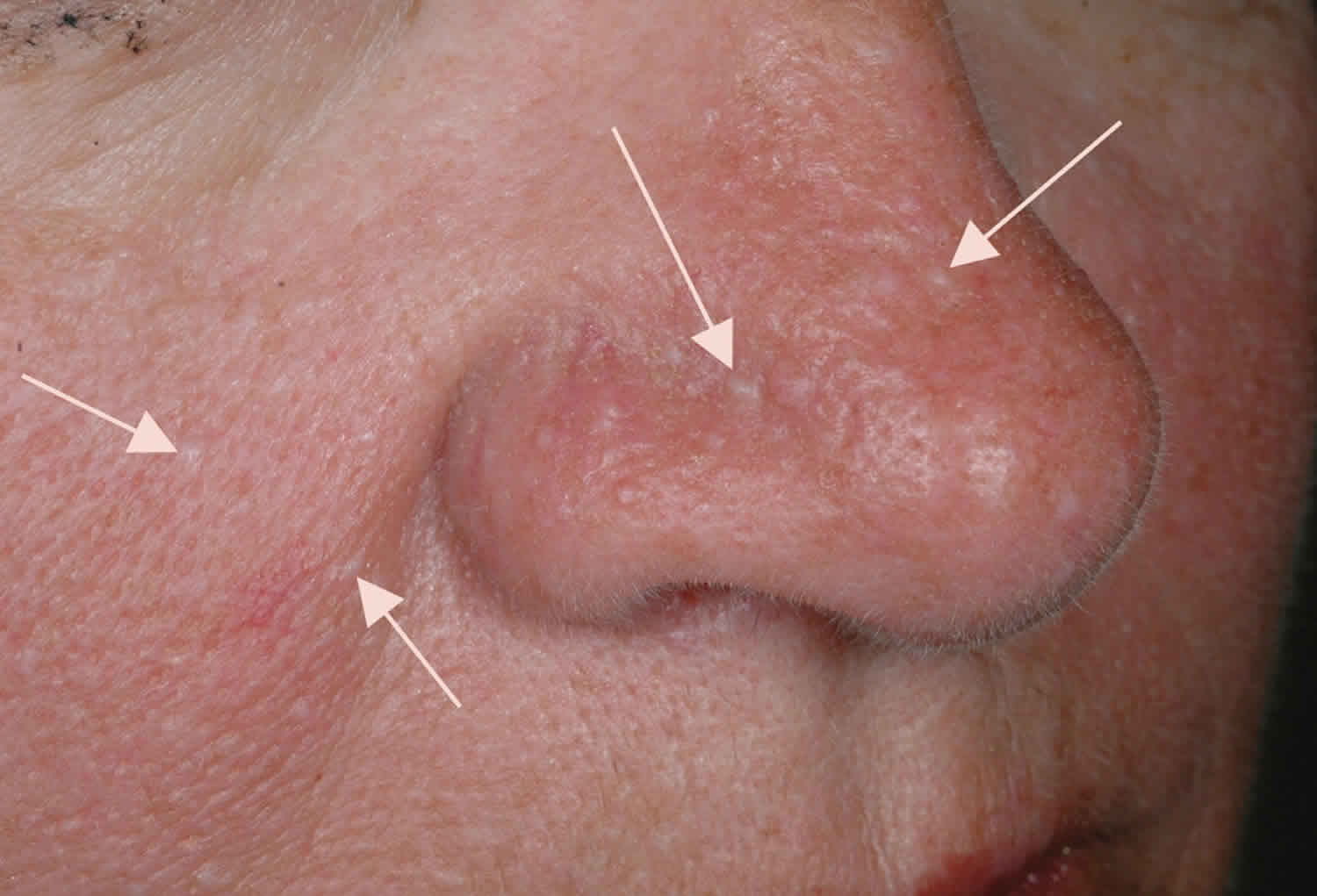

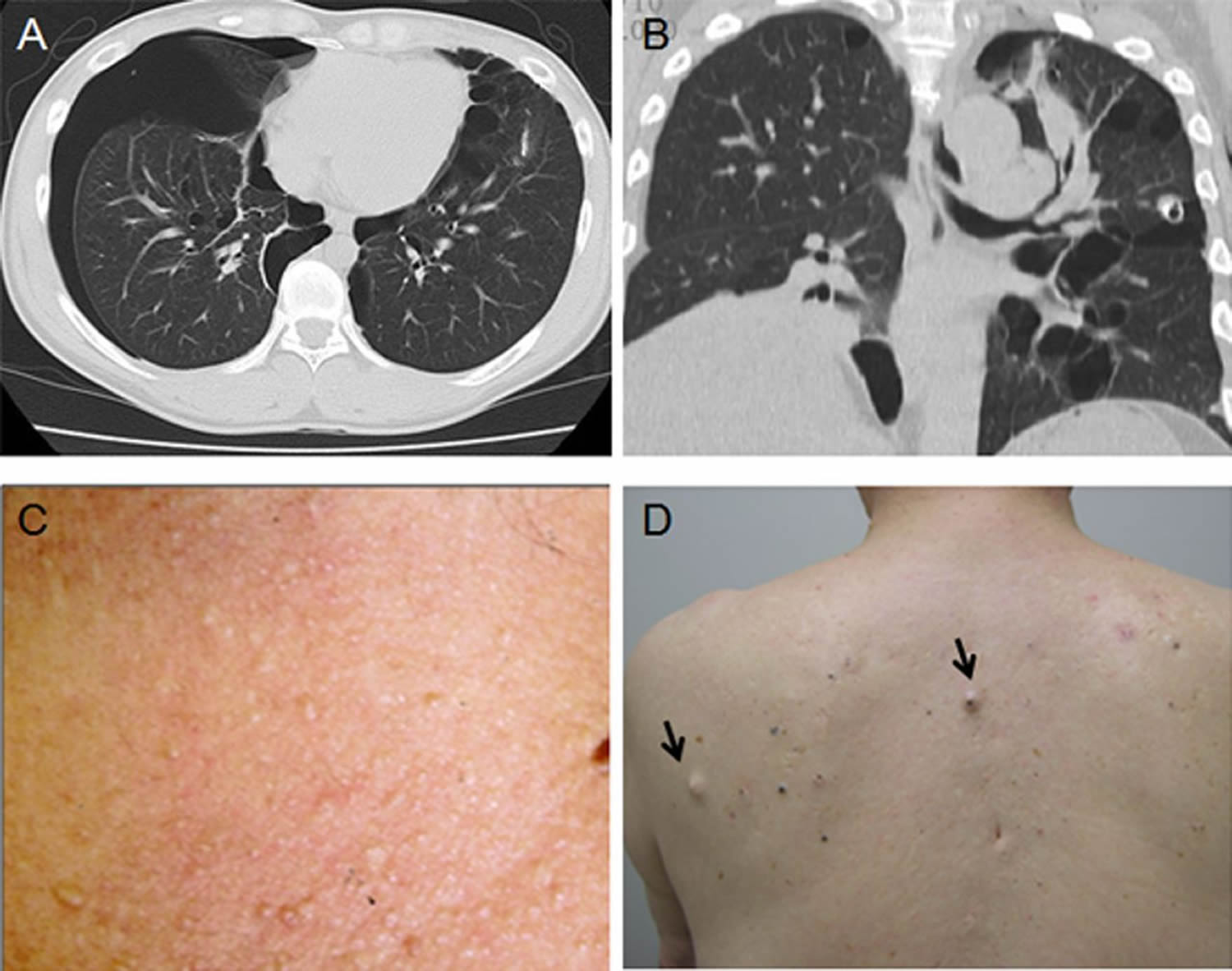

Figure 1. Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome

Footnote: Thoracic CT scans and skin tumours of patients with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. (A) A 33-year-old woman who had a pneumothorax six times showing cysts localised in the perimediastinal subpleura. (B) A 53-year-old woman who had a pneumothorax twice showing most of the cysts in contact with the interlobular septum. (C) A 69-year-old woman with renal cell carcinoma who had multiple skin papules on the neck. (D) A 76-year-old man with a few flat-topped fibrous papules on the back (arrows).

[Source 3 ]Is there a cure for Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome?

There is currently no cure for Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome.

How many people with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome get each symptom?

- 9 in 10 people with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome develop skin lesions

- 9 in 10 people with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome develop lung cysts

- 1 in 4 people get a collapsed lung

- 1 in 3 people get kidney cancer.

Can I fly or go scuba diving if I have Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome?

Sudden changes in air pressure can increase the chances of developing a collapsed lung, so it might be sensible to avoid activities where you will be exposed to large changes in air pressure (such as flying in unpressurised planes or scuba diving) 4.

However, if you are a keen scuba diver and have not previously had problems, or if it is a lifetime ambition of yours to go diving, it might be possible for you to continue with these activities if your doctor thinks it is ok, if you are hyper-vigilant to symptoms, and if you warn your flying/ diving mates of the potential risks.

Researchers have found that a small number of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome patients (1 in 16) develop a pneumothorax up to a month after taking a commercial flight. Their advice is to be alert to any symptoms of a collapsed lung after flying, and if you develop any symptoms, however minor, to get a chest X-Ray as soon as possible. They also suggest that you take a copy of this study (https://www.bhdsyndrome.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Postmus-et-al.-2014.pdf) with you to show your doctor.

What is the best way to treat the cysts that develop on the lungs as a result of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome?

At the time of diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, a computed tomography (CT) scan, or high resolution CT scan if available, should be done to determine the number, location, and size of any cysts in the lungs 1. There is no recommended management of the lung cysts. Lung cysts related to Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome have not been associated with long-term disability or fatality 5. The main concern is that the cysts may increase the chance of developing a collapsed lung (pneumothorax).

If an individual with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome experiences any symptoms of a collapsed lung – such as chest pain, discomfort, or shortness of breath – they should immediately go to a physician for a chest x-ray or CT scan 1. Therapy of a collapsed lung depends on the symptoms, how long it has been present, and the extent of any underlying lung conditions 5. It is thought that collapsed lung can be prevented by avoiding scuba diving, piloting airplanes, and cigarette smoking 5.

Individuals with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome who have a history of multiple instances of collapsed lung or signs of lung disease are encouraged to see a lung specialist (pulmonologist) 6.

At what age do the symptoms of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome develop?

On average, people with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome start developing skin lesions after the age of 20, have their first pneumothorax in their mid-thirties, and develop kidney cancer in their late-forties or early fifties.

However, there are always exceptions. For example, we know of at least five children with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome who had their first pneumothorax under the age of 18, and of at least two patients who developed kidney cancer in their twenties.

Do my children have Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome?

If you have Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, each of your children has a 50:50 chance of inheriting Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome.

In most cases, Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome symptoms develop after the age of 20, so many people choose to wait until their child is old enough to decide for themselves if they want to have the genetic test.

However, there have been five reported cases of children having recurrent episodes of pneumothorax, and later being diagnosed with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, so as a parent, you should be aware of this (very small) risk.

How can I have Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome if no one else in my family has Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome?

There are two possible explanations for this:

Firstly, it is possible that you developed a mutation in the Folliculin gene when you were an embryo and are the first person in your family to have Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. This is called a “de novo” mutation. There has only been one reported instance of a de novo case of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome.

As de novo cases of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome are so rare, it is far more likely that one of your parents and other older family members do have Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, but they just haven’t been diagnosed for some reason.

Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome wasn’t described until the late 1970s, so any patients showing symptoms before then simply would not have been diagnosed. Additionally, as Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome is so rare many doctors have not heard of it, so it is possible that your family members did have the symptoms, but their doctors did not diagnose them correctly.

Alternatively, just under half of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome patients will never get a collapsed lung or kidney tumour. Lung cysts by themselves rarely show symptoms, and some people don’t get many skin lesions. It could just be that your family members were in this lucky group of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome patients who never had too many symptoms, and so although they had Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, it never caused them any health problems, so they never went to the doctor for a diagnosis.

Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome causes

Mutations in the FLCN gene located on chromosome 17p11.2 cause Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. The FLCN gene provides instructions for making a protein called folliculin. The normal function of this protein is unknown, but researchers believe that it may act as a tumor suppressor. Tumor suppressors prevent cells from growing and dividing too rapidly or in an uncontrolled way. FLCN has been linked to the mTOR pathway 2. Mutations in the FLCN gene may interfere with the ability of folliculin to restrain cell growth and division, leading to uncontrolled cell growth and the formation of noncancerous and cancerous tumors. Researchers have not determined how FLCN mutations increase the risk of lung problems, such as pneumothorax.

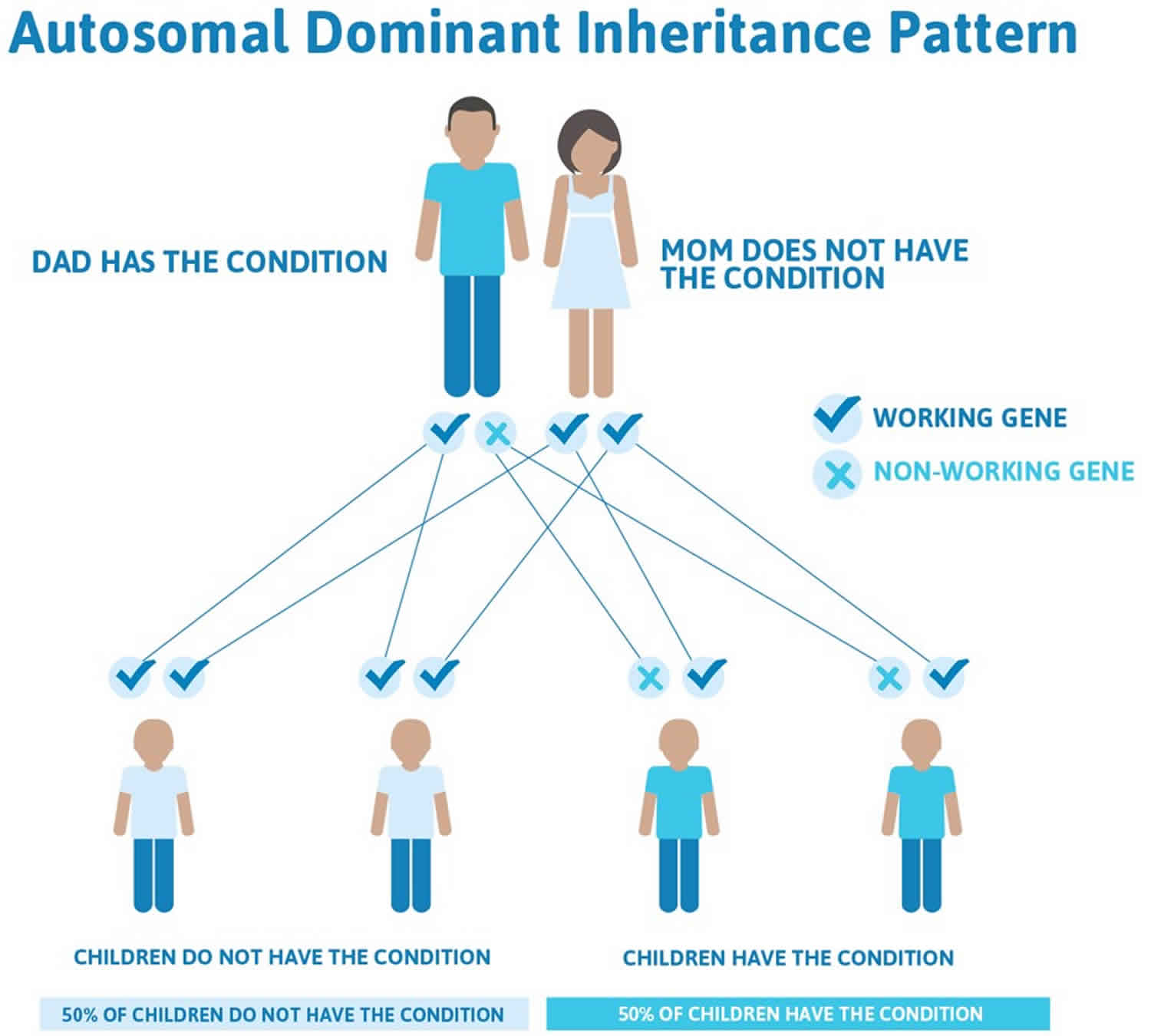

Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome inheritance pattern

This condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means one copy of the altered FLCN gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder. In most cases, an affected person inherits the mutation from one affected parent. Less commonly, the condition results from a new mutation in the gene and occurs in people with no history of the disorder in their family.

Having a single mutated copy of the FLCN gene in each cell is enough to cause the skin tumors and lung problems associated with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. However, both copies of the FLCN gene are often mutated in the kidney tumors that occur with this condition. One of the mutations is inherited from a parent, while the other occurs by chance in a kidney cell during a person’s lifetime. These genetic changes disable both copies of the FLCN gene, which allows kidney cells to divide uncontrollably and form tumors.

In cases where the autosomal dominant condition does run in the family, the chance for an affected person to have a child with the same condition is 50% regardless of whether it is a boy or a girl. These possible outcomes occur randomly. The chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys and girls.

- When one parent has the abnormal gene, they will pass on either their normal gene or their abnormal gene to their child. Each of their children therefore has a 50% (1 in 2) chance of inheriting the changed gene and being affected by the condition.

- There is also a 50% (1 in 2) chance that a child will inherit the normal copy of the gene. If this happens the child will not be affected by the disorder and cannot pass it on to any of his or her children.

There are cases of autosomal dominant gene changes, or mutations, where no one in the family has it before and it appears to be a new thing in the family. This is called a de novo mutation. For the individual with the condition, the chance of their children inheriting it will be 50%. However, other family members are generally not likely to be at increased risk.

Figure 2 illustrates autosomal dominant inheritance. The example below shows what happens when dad has the condition, but the chances of having a child with the condition would be the same if mom had the condition.

Figure 2. Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome symptoms

Three major features characterize Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome 2:

Cutaneous manifestations

Individuals with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome usually present with multiple, small, skin-colored, dome-shaped papules distributed over the face, neck, and upper trunk. The original characteristic dermatologic triad was fibrofolliculomas, trichodiscomas, and acrochordons 7; however, only fibrofolliculomas are specific for Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Perifollicular fibromas and angiofibromas have also been associated with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Trichodiscomas are essentially histologically and clinically indistinguishable from angiofibromas; the term trichodiscoma has been used to describe angiofibromas when they occur in the setting of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome.

The dermatologic diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome is made in individuals who have five or more facial or truncal papules with at least one histologically confirmed fibrofolliculoma 7:

- Fibrofolliculomas are defined as multiple anastomosing strands of two to four epithelial cells extending from a central follicle. Sometimes a well-demarcated, mucin-rich, or thick connective tissue stroma encapsulates the epithelial component. Biopsy is required to make the diagnosis.

- Note: Shave biopsy is usually not adequate. More than one skin-punch biopsy and sectioning of the paraffin-embeded block is sometimes needed to make the diagnosis of fibrofolliculoma.

- Trichodiscomas are hamartomatous lesions comprising a round to elliptically shaped well-demarcated proliferation of thick fibrous and vascular stroma in the reticular dermis with a hair follicle at the periphery. Because of the high density of hair follicles in the face, hair follicles are commonly found at the periphery of these lesions. Angiofibromas are clinically and histologically essentially the same as trichodiscomas.

- Note: Trichodiscomas/angiofibromas are suggestive for the diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome but not diagnostic. Angiofibromas are commonly also found in tuberous sclerosis complex and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1).

- Acrochordons or skin tags, are soft pedunculated papules that histologically are characterized by acanthotic and mild papillomatous epidermis with loose connective tissue stroma and blood vessels.

- Perifollicular fibromas are well-demarcated proliferations of fibrous and vascular stroma in the reticular dermis surrounding a hair follicle.

Lung cysts and spontaneous pneumothorax

Most individuals (89%) with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome have multiple bilateral lung cysts, identified by high-resolution chest CT. The total number of lung cysts per individual ranges from 0 to 166 (mean 16). Forty-eight (24%) of 198 individuals with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome had a history of one or more pneumothoraces 8.

All individuals with a history of pneumothorax had multiple lung cysts identified by high-resolution chest CT imaging. Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome-related lung cysts abutted on interlobular septa (88.2%) and had intracystic septa (13.6%) or protruding venules (39.5%) without cell proliferation or inflammation. Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome-related lung cysts are likely to develop in the periacina region where alveoli attach to connective tissue 9.

Renal tumors

The renal tumors are usually bilateral and multifocal. Histologic tumor types include: hybrid oncocytic renal cell carcinoma, oncocytoma, chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, and a minority of clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

Note: FLCN nucleotide variants have been identified in certain tumors. The original description and diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome is based on skin pathology. However, recent investigations have shown that some individuals with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome could present with pulmonary involvement and/or renal tumors without skin lesions.

Parotid oncocytoma

The first case of an individual with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome who developed a parotid oncocytoma was reported in 2000 10. Subsequently multiple cases have been reported 11. Additionally, one person with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome has been reported with a pleomorphic adenoma 12 and another individual with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome has been reported with a Warthin parotid tumor 13. Two cases of bilateral parotid tumors have also been reported 14. The frequency and the bilateral, multifocal nature of these tumors in individuals with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome who have not undergone specific screening for parotid tumors suggest that parotid tumors are a manifestation of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome.

Oral papules

Oral papules have been reported in nine (43%) of 21 individuals with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome in a large French case series 15 and in several other reports 16.

Other findings

- Thyroid pathology. Three cases of thyroid cancer in affected individuals have been reported [Toro et al 2008, Kunogi et al 2010]. Multinodular goiter [Drummond et al 2002, Welsch et al 2005] and thyroid nodules and/or cysts have also been reported. In a French case series, thyroid nodules and/or cysts were detected by ultrasonography in 13 (65%) of 20 individuals with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome; no medullary carcinoma or other thyroid carcinomas were detected. None of the affected individuals with thyroid nodules and/or cysts had a familial history of thyroid cancer. Overall, nine (90%) of ten families affected by Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome with germline pathogenic variants in FLCN had individuals with thyroid nodules [Kluger et al 2010].

- Colon cancer. Multiple cases of colon cancer have been described in affected individuals [Toro et al 2008], but the evidence associating colonic neoplasm and Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome is conflicting [Khoo et al 2002, Zbar et al 2002] (see Genotype-Phenotype Correlations and Molecular Genetics).

- Other tumor types have been reported rarely in individuals with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome:

- Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck 17

- Hodgkin disease 17

- Uterine cancer 17

- Prostate cancer 17

- Breast cancer 18

- Squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix 17

- Rhabdomyoma 17

- An adrenal mass and adenoma of adrenal gland [Toro et al 2008, Kunogi et al 2010]

- Myoma of the uterus 18

- Lipoma, angiolipoma, and collagenoma 7

- Cutaneous neural tumors: neurothekeoma (benign myxoma of cutaneous nerve sheath origin), meningioma 19 and multiple neurilemmomas 20

- Ovarian cyst 21

- Parathyroid adenoma 22

- Chorioretinal lesions 21

- Neuroendocrine carcinoma 23

Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome diagnosis

Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome is diagnosed by clinical findings and by molecular genetic testing. FLCN (also known as BHD) is the only gene known to be associated with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Sequence analysis detects pathogenic variants in FLCN in 88% of affected families, whereas 3%-5% have partial- or whole-gene deletions identified by other methods. Therefore, approximately 7%-9% of affected individuals who fulfill clinical diagnostic criteria do not have an identifiable FLCN pathogenic variant.

Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome treatment

Laser ablation of folliculoma/trichodiscoma results in substantial improvement for a period of time, but relapse usually occurs. Pneumothoraces are treated as in the general population. When possible, nephron-sparing surgery is the treatment of choice for renal tumors, depending on their size and location.

Surveillance: Periodic MRI of the kidneys is the optimal screening modality to assess for kidney lesions; abdominal/pelvic CT scan with contrast is an alternative when MRI is not an option, but the long term effects of cumulative radiation exposure is unknown; full body skin examination at routine intervals to evaluate for melanoma should be considered.

- Renal tumor screening

- Renal imaging is appropriate for individuals age 18 years or older when the clinical diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome is established or if a pathogenic variant in FLCN is confirmed. However, earlier testing and surveillance for renal tumors should be personalized based on family history of renal tumor development, when available.

- Yearly MRI of the kidneys is the optimal screening modality to assess for kidney lesions.

- Abdominal/pelvic CT scan with contrast is an alternative when MRI is not an option. However, the long-term effects of cumulative radiation exposure in individuals with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome is unknown and has not been studied.

- As a result of the low aggressiveness of kidney tumors and the 3.0-cm rule used by surgeons in treating renal tumors 24, affected individuals without a family history of kidney tumors who have had two to three consecutive annual MRI examinations without the detection of kidney lesions may be screened every two years until a suspicious lesion is identified.

- Note: The use of renal ultrasound examination is helpful in further characterization of kidney lesions but should not be used as a primary screening modality.

- If any suspicious lesion (<1.0 cm in diameter, indeterminate lesion, or complex cysts) is noted on screening examination, annual MRI should be instituted. Abdominal/pelvic CT scan with contrast may be used as an alternative in those for whom MRI is not an option.

- Renal tumors <3.0 cm in diameter are monitor by periodic imaging. When the largest renal tumor reaches 3.0 cm in maximal diameter evaluation by a urologic surgeon is appropriate with consideration of nephron-sparing surgery 25.

- Rapidly growing lesions and/or symptoms including pain, blood in the urine, or atypical presentations require a more individualized approach. PET-CT scan is an option for evaluation of these lesions.

- Melanoma: Because of a concern for a possible increased risk of melanoma in those with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, full body skin examination at routine intervals to evaluate for suspicious pigmented lesions should be considered.

Agents/circumstances to avoid: Cigarette smoking, high ambient pressures, and radiation.

Evaluation of relatives at risk: When the family-specific pathogenic variant is known, use of molecular genetic testing for early identification of at-risk family members improves diagnostic certainty and reduces costly screening procedures in at-risk members who have not inherited the pathogenic variant. Early recognition of clinical manifestations may allow timely intervention and improve outcome. Therefore, clinical surveillance of asymptomatic at-risk relatives for early detection is appropriate.

Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome life expectancy

As long as they are treated correctly, pneumothoraces are rarely life-threatening, although it may not feel like this when you are in the middle of an episode.

The only life-threatening symptom of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome is the kidney cancer. However, when they first develop, the tumours are normally unaggressive (benign), and they don’t usually spread unless they are larger than 4 cm in diameter. This is why Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome experts recommend getting regular scans to monitor your kidneys and removing any tumours when they reach 3 cm.

Compared with the number of people that have Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, there are only a few reports of people dying from the kidney cancer. In many cases, the patient didn’t know they had Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, so by the time they were diagnosed the tumour had spread to other parts of the body. This means that so long as you get regular scans, your chances of dying from kidney cancer are dramatically reduced.

References- Toro JR. Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome. 2006 Feb 27 [Updated 2014 Aug 7]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2019. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1522

- Crane JS, Rutt V, Oakley AM. Birt Hogg Dube Syndrome. [Updated 2019 Apr 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448061

- Furuya M, Nakatani Y. Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome: clinicopathological features of the lung. Journal of Clinical Pathology 2013;66:178-186. https://jcp.bmj.com/content/66/3/178

- Wajda N, Gupta N. Air Travel-Related Spontaneous Pneumothorax in Diffuse Cystic Lung Diseases. Curr Pulmonol Rep. 2018 Jun;7(2):56-62.

- Toro JR, Pautler SE, Stewart L, Glenn GM, Weinreich M, Toure O, Wei MH, Schmidt LS, Davis L, Zbar B, Choyke P, Steinberg SM, Nguyen DM, Linehan WM. Lung cysts, spontaneous pneumothorax, and genetic associations in 89 families with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2007; 175(10):1044-1053.

- Menko FH, van Steensel, MA, Giraud S, Friis-Hansen L, Richard S, Ungari S, Nordenskjöld M, O Hansen TV, Solly J, Maher, ER. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: diagnosis and management. The Lancet Oncology. 2009; 10(12):1199-1206. https://www.bhdsyndrome.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/Menko-et-al-20091.pdf

- Toro JR, Glenn G, Duray P, Darling T, Weirich G, Zbar B, Linehan M, Turner ML. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a novel marker of kidney neoplasia. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1195–202.

- Toro JR, Pautler SE, Stewart L, Glenn GM, Weinreich M, Toure O, Wei MH, Schmidt LS, Davis L, Zbar B, Choyke P, Steinberg SM, Nguyen DM, Linehan WM. Lung cysts, spontaneous pneumothorax, and genetic associations in 89 families with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1044–53.

- Kumasaka T, Hayashi T, Mitani K, Kataoka H, Kikkawa M, Tobino K, Kobayashi E, Gunji Y, Kunogi M, Kurihara M, Seyama K. Characterization of pulmonary cysts in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: histopathological and morphometric analysis of 229 pulmonary cysts from 50 unrelated patients. Histopathology. 2014;65:100–10.

- Liu V, Kwan T, Page EH. Parotid oncocytoma in the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:1120–2.

- Toro JR, Wei MH, Glenn GM, Weinreich M, Toure O, Vocke C, Turner M, Choyke P, Merino MJ, Pinto PA, Steinberg SM, Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. BHD mutations, clinical and molecular genetic investigations of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a new series of 50 families and a review of published reports. J Med Genet. 2008;45:321–31.

- Palmirotta R, Donati P, Savonarola A, Cota C, Ferroni P, Guadagni F. Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome: report of two novel germline mutations in the folliculin (FLCN) gene. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:382–6.

- Maffé A, Toschi B, Circo G, Giachino D, Giglio S, Rizzo A, Carloni A, Poletti V, Tomassetti S, Ginardi C, Ungari S, Genuardi M. Constitutional FLCN mutations in patients with suspected Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome ascertained for non-cutaneous manifestations. Clin Genet. 2011;79:345–54.

- Lindor NM, Kasperbauer J, Lewis JE, Pittelkow M. Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome presenting as multiple oncocytic parotid tumors. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2012;10:13.

- Kluger N, Giraud S, Coupier I, Avril MF, Dereure O, Guillot B, Richard S, Bessis D. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: clinical and genetic studies of 10 French families. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:527–37

- Toro JR, Glenn G, Duray P, Darling T, Weirich G, Zbar B, Linehan M, Turner ML. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a novel marker of kidney neoplasia. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1195–202

- Toro JR, Wei MH, Glenn GM, Weinreich M, Toure O, Vocke C, Turner M, Choyke P, Merino MJ, Pinto PA, Steinberg SM, Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. BHD mutations, clinical and molecular genetic investigations of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a new series of 50 families and a review of published reports. J Med Genet. 2008;45:321–31

- Kunogi M, Kurihara M, Ikegami TS, Kobayashi T, Shindo N, Kumasaka T, Gunji Y, Kikkawa M, Iwakami S, Hino O, Takahashi K, Seyama K. Clinical and genetic spectrum of Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome patients in whom pneumothorax and/or multiple lung cysts are the presenting feature. J Med Genet. 2010;47:281–7.

- Vincent A, Farley M, Chan E, James WD. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: two patients with neural tissue tumors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:717–9

- Renfree KJ, Lawless KL. Multiple neurilemmomas in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:792–4

- Godbolt AM, Robertson IM, Weedon D. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:52–6

- Chung JY, Ramos-Caro FA, Beers B, Ford MJ, Flowers F. Multiple lipomas, angiolipomas, and parathyroid adenomas in a patient with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:365–7

- Claessens T, Weppler SA, van Geel M, Creytens D, Vreeburg M, Wouters B, van Steensel MA. Neuroendocrine carcinoma in a patient with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:583–7

- Pavlovich CP, Grubb RL 3rd, Hurley K, Glenn GM, Toro J, Schmidt LS, Torres-Cabala C, Merino MJ, Zbar B, Choyke P, Walther MM, Linehan WM. Evaluation and management of renal tumors in the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. J Urol. 2005;173:1482–6

- Stamatakis L, Metwalli AR, Middelton LA, Marston Linehan W. Diagnosis and management of BHD-associated kidney cancer. Fam Cancer. 2013;12:397–402.