Sengstaken Blakemore tube

Sengstaken-Blackmore tube is used in an emergency situation for an acute esophageal variceal bleeding 1. However, the arrival of endoscopy has reduced the use of balloon tamponade, but the use of Sengstaken-Blackmore tube can still be lifesaving, despite their potential for serious complications 2. Recent World Gastroenterology Organisation Global guideline still suggests a role for balloon tamponade; however, it should only be used as a temporary measure in massive variceal hemorrhage until definitive treatment when endoscopic therapy fails or is not possible 2.

The Sengstaken-Blakemore tube was originally described in 1950 by Sengstaken and Blakemore 3. The effectiveness of Sengstaken-Blakemore tube for hemostasis in initial control of variceal hemorrhage was reportedly 50% to 90% until 1980 4. However, since the era of the endoscopic band ligation, bleeding control rate for variceal hemorrhage was 80% to 97% 5. In a recent Choi et al study 6, the overall success rate of initial hemostasis by Sengstaken-Blakemore tube was 75.8% in acute uncontrolled variceal hemorrhage patients in whom endoscopic therapy had failed or was not possible, which was comparable to the reported rate before the era of endoscopic band ligation. Among 50 patients who achieved bleeding control with Sengstaken-Blakemore tube, 11 had rebleeding. Esophageal perforation was encountered in four patients. The overall mortality rate within 30 days was 42.4%, but overall mortality rate in the 50 patients who achieved initial control was 24.0%. Independent predictors related to initial hemostasis were non-intubated state before Sengstaken-Blakemore tube insertion and Child-Pugh score < 11. Moreover, independent risk factors related to overall mortality were failure of initial hemostasis with Sengstaken-Blakemore tube and endotracheal intubation before Sengstaken-Blakemore tube insertion.

In another study aimed at determining the effect of controlling variceal hemorrhage with a balloon tamponade device (eg, Minnesota or Sengstaken-Blakemore tube) on patient outcomes, Nadler et al 7 assessed survival to discharge, survival to 1 year, and development of complications. Approximately 59% of patients survived to discharge, and 41% were alive after 1 year. One complication, esophageal perforation, was noted; it was managed conservatively.

Variceal hemorrhage is a life-threatening emergency and a major cause of death in patients with liver cirrhosis. The mortality of acute variceal hemorrhage is reportedly 20% at 6 weeks 8. Until 1980, the main management of acute variceal hemorrhage was based on balloon tamponade 9. Current recommendation for acute variceal hemorrhage in patients with liver cirrhosis is combined management with vasoactive drugs, endoscopic therapy, and prophylactic antibiotics 8. This change has resulted in a great improvement in mortality from 42.6% in 1980 to 14.5% in 2000 since the era of the endoscopic band ligation 10. Prior to the 1970s, surgical shunting was used as a rescue therapy for uncontrolled variceal hemorrhage, but was superseded by the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in the late 1990s 11.

Generally, the esophageal tamponade tube is a temporary measure and should not be left in place for more than 24 hours. Direct pressure from the tube can cause mucosal ulceration. Perform frequent examinations to ensure that the Sengstaken-Blackmore tube is not placing excessive force on any given surface.

In conclusion, Sengstaken-Blakemore tube might be a beneficial option in rescue therapy for uncontrolled variceal hemorrhage if emergency transjugular intrahepatic portacaval shunting (TIPS) is not available, but lethal esophageal complications due to Sengstaken-Blakemore tube still occurred. Lower Child-Pugh score and non-intubated state before Sengstaken-Blakemore tube insertion were independent factors for initial hemostasis with Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. In addition, failure of initial hemostasis with Sengstaken-Blakemore tube and endotracheal intubation before Sengstaken-Blakemore tube were independent risk factors related to overall mortality. Based on these findings, experts recommend careful insertion of the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube, especially in patients with endotracheal intubation 6.

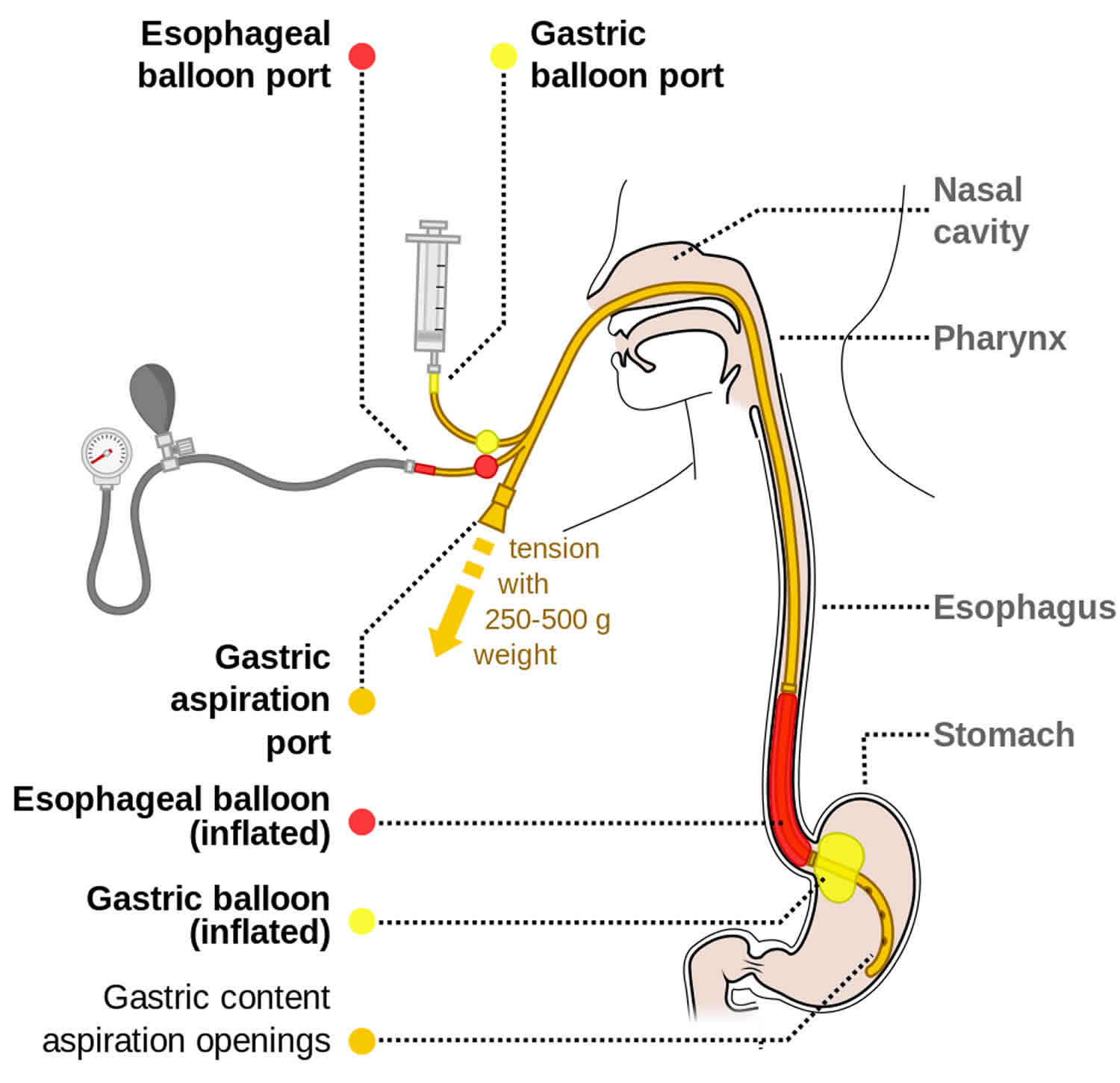

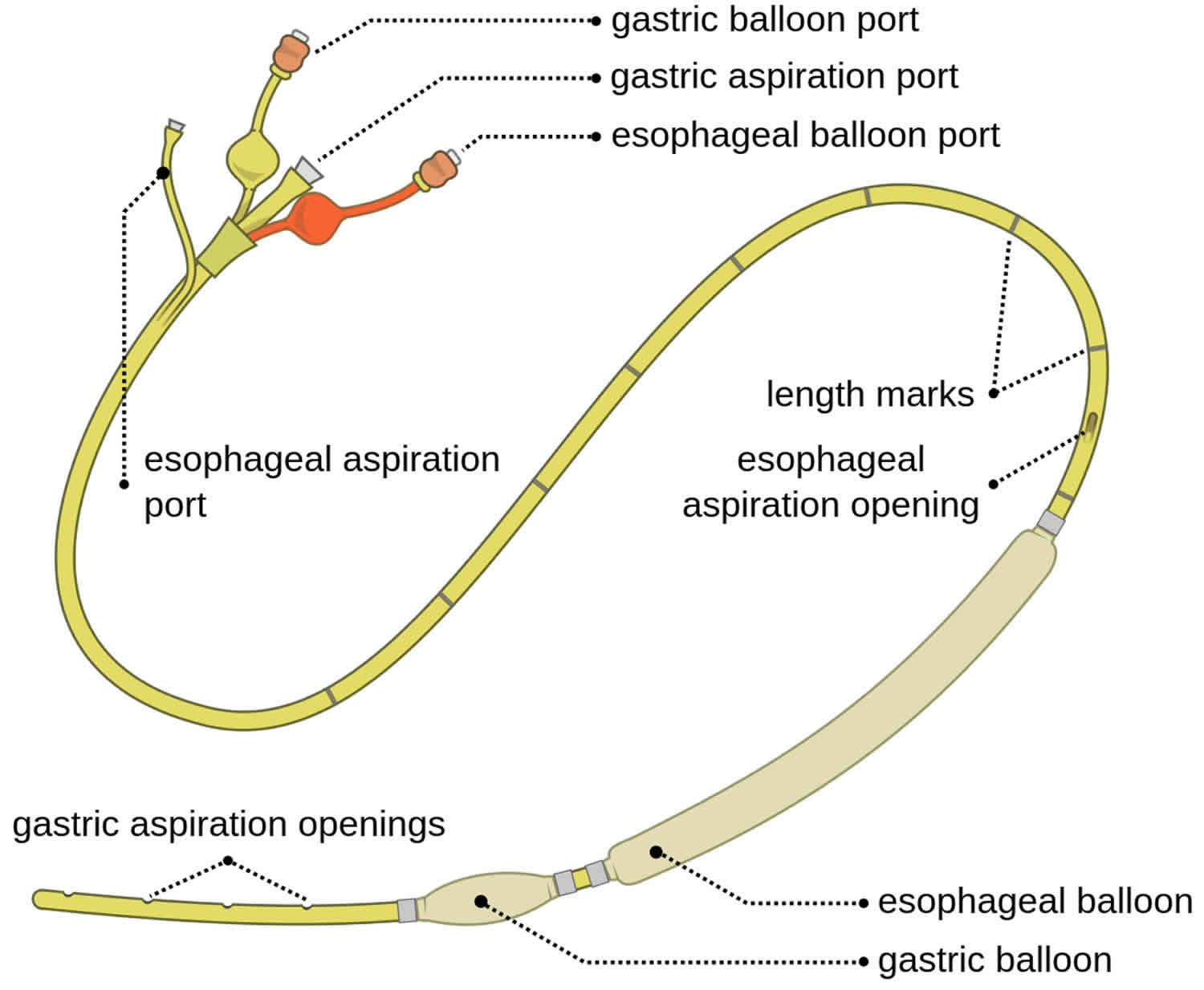

The three major components of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube are as follows (see Figure 1 below):

- Gastric balloon

- Esophageal balloon

- Gastric suction port

The addition of an esophageal suction port to help prevent aspiration of esophageal contents resulted in what is called the Minnesota tube. Another nasogastric device with a single gastric balloon is most effective at terminating bleeding from gastric varices and is known as the Linton-Nachlas tube.

Figure 1. Sengstaken Blakemore tube

Sengstaken Blakemore tube contraindications

Contraindications for placement of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube include the following:

- Variceal bleeding stops or slows

- Recent surgery that involved the esophagogastric junction

- Known esophageal stricture

Sengstaken Blakemore tube uses

Indications for placement of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube include the following:

- Acute life-threatening bleeding from esophageal or gastric varices that does not respond to medical therapy (including endoscopic hemostasis and vasoconstrictor therapy) 12

- Acute life-threatening bleeding from esophageal or gastric varices when endoscopic hemostasis and vasoconstrictor therapy are unavailable

Chen et al 13 described a case in which a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube was successfully used for nonvariceal distal esophageal bleeding (from severe ulcerative esophagitis) after conventional medical and endoscopic therapy had failed.

A novel use of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube to tamponade oropharyngeal hemorrhage during exploration of a carotid injury was reported by Bensley et al 14.

Sengstaken Blakemore tube insertion

Equipment used for placement of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube includes the following:

- Gastroesophageal balloon tamponade tube

- Y-tube connector or similar adapter, if not already part of the tamponade balloon ports (see the first and second images below)

- Traction device or setup (see the third image below)

- Manual manometer or sphygmomanometer (see the fourth image below)

- Vacuum suction device with suction tubing and connectors (see the fifth image below)

- Tube clamps (4)

- Large (60 mL) irrigating syringe (catheter tip)

- Soft restraints

- Water-soluble lubricating jelly

- Scissors for emergency balloon decompression

Testing the Sengstaken–Blackmore tube

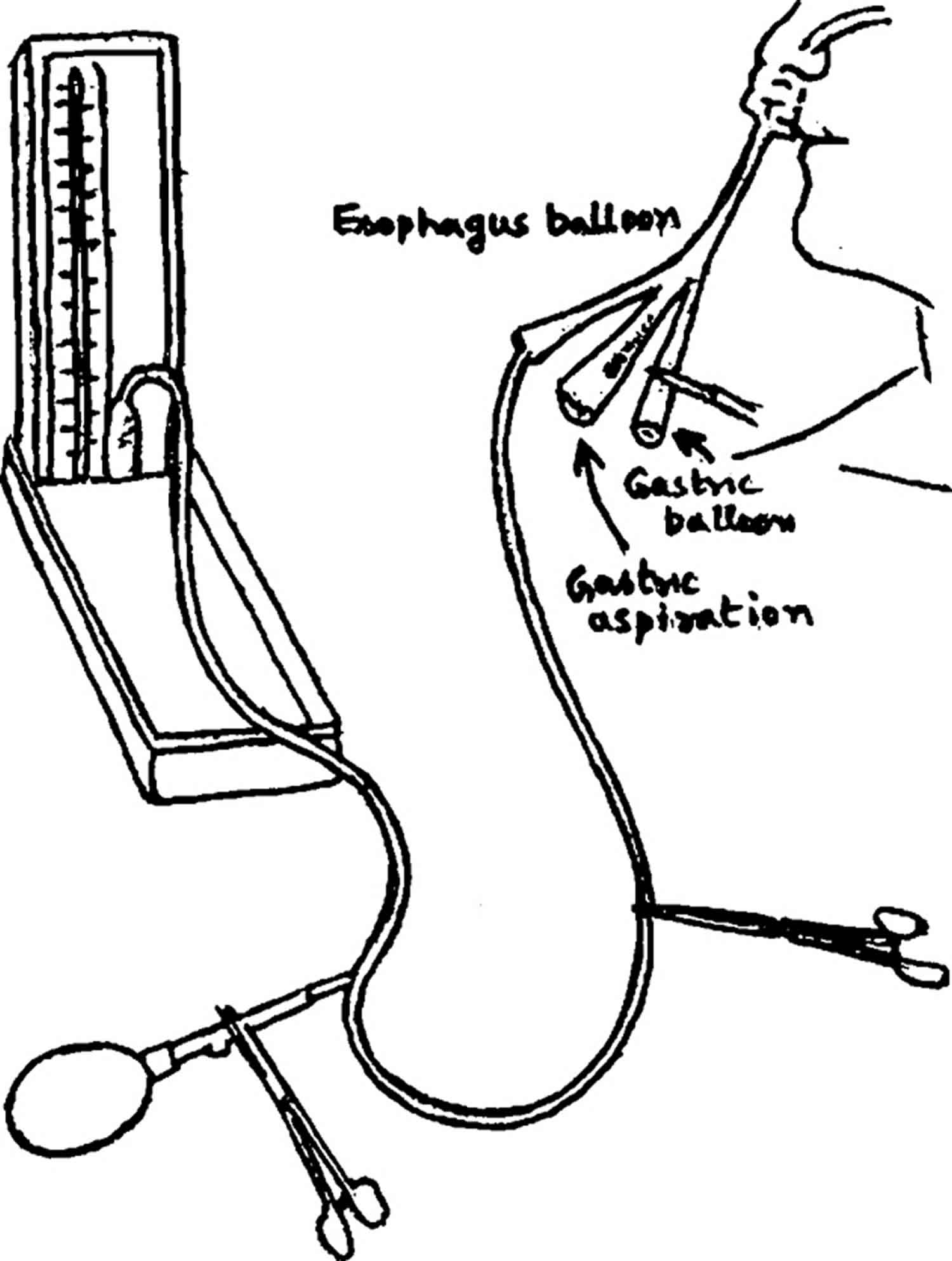

- Test the functioning of the bulbs before passing Blackmore tube at the pressure of 70 mm of Hg by connecting it with the sphygmomanometer as shown in Figure 2.

- If the gastric and / or esophageal bulbs show any evidence of leak (tested by submerging the bulbs underwater) the rubber of the bulbs should be peeled off from the tube. It usually leaves three rough impressions where the rubber bulbs are attached with the tube. Take a condom and make a small opening at its tip and pass the tube through the condom and tie the condom using a fine silk suture (1/10). By tying at three places two bulbs are formed i.e. gastric and esophageal bulbs 1.

- Inflate the bulbs and test for the leakage as in step 1. If there is no leak the tube is ready to be used.

Figure 2. Testing the Sengstaken Blakemore tube

Patient preparation

Topical anesthetic (spray and jelly) is used for the oropharynx. Intubation and sedation are indicated for most patients.

Elevate the head of the bed to 45°, and position the patient on the bed. The left lateral decubitus position is an acceptable alternative.

Control of the patient is essential. Routine use of soft restraints and medications for sedation should be considered in most patients.

In view of the extremely high risk of regurgitation and aspiration, the threshold for performing endotracheal intubation should be low. To minimize this risk, nasogastric (NG) lavage and maximal stomach evacuation should be carried out before placement of an esophageal tamponade tube.

Ensure that all the appropriate equipment is present. Keep a pair of scissors near the patient at all times in case the balloons migrate superiorly and obstruct the airway. The whole tube can be cut and removed.

Ensure that the balloons on the tamponade tube are free of leaks; optimally, balloon integrity should be tested while the balloons are submerged under water.

- An optional step is as follows: If monitoring gastric balloon pressure, inflate the gastric balloon in increments (typically 100 mL) up to the maximum recommended volume (usually 500 mL) while the pressure is measured with the manometer. Note the pressure at each given volume.

- Another optional step is the following: If the nasogastric tube is used, tie it along the course of the tube with silk sutures, with the tip of the nasogastric tube 3-4 cm proximal to the esophageal balloon. This step is not required if the tube is one that has esophageal aspiration ports (eg, a Minnesota tube).

Position the patient appropriately, and anesthetize the posterior pharynx and nostrils with a topical anesthetic.

Suction all air from the gastric and esophageal balloons.

Clamp the balloon ports or insert the plastic plugs into the lumens (if provided with the tube).

Coat the balloons on the tube with water-soluble lubricating jelly. Pass the tube to at least the 50-cm mark. The tube can be passed through the nostrils or, preferably, through the mouth. The oral route is especially preferred in intubated patients.

Apply suction to the gastric and esophageal aspiration ports.

- A third optional step is as follows: If monitoring gastric balloon pressure, remove the tube clamps (or plastic plugs, if used) from the gastric balloon inflation ports. Introduce increments of air (usually 100 mL) through the gastric balloon inflation port while the pressure is again measured with the manometer. If, at any given increment, the gastric balloon pressure is 15 mm Hg greater than readings previously obtained during testing (ie, before intubation), then deflate the balloon; it may be located in the esophagus.

In most cases, the esophageal balloon is not inflated during the initial placement of the tube. Never inflate the esophageal balloon before the gastric balloon.

When the gastric balloon is correctly positioned in the stomach, inflate it with the full recommended volume of air (usually 450-500 mL), then clamp the air inlet and pressure-monitoring outlet. Check proper placement by irrigating the gastric aspiration port with water while auscultating over the stomach. If correct tube placement is at all uncertain or if time permits, obtain a portable chest radiograph.

Pull the tube back gently until resistance is felt against the diaphragm.

Secure the proximal end of the tube using a traction device. A pulley device can be used to maintain the desired 0.45-0.9 kg (1-2 lb) of traction. A 500-mL bag of intravenous fluid can serve as a convenient initial weight. Alternatively, tubes can be secured with tape to the mouth guard of a football helmet. A foam rubber cuff, which is generally included in the package with the tube itself, can be used to maintain traction against the nose if the tube has been inserted through the nostrils.

If bleeding persists from the gastric aspiration port (or from the esophageal aspiration port on a four-lumen tube), inflate the esophageal balloon to the lowest pressure needed to stop bleeding (usually 30-45 mm Hg), then clamp the port for the esophageal balloon. Check the balloon pressure periodically.

If bleeding persists from the gastric aspiration port after inflation of the gastric and esophageal balloons, increase the external traction on the tube (to a maximum of 1.1 kg [2.5 lb]). In this case, the bleeding typically originates from a gastric rather than an esophageal varix.

Confirm correct tube position with an immediate portable radiograph.

After bleeding has been controlled, reduce the pressure in the esophageal balloon by 5 mm Hg every 3 hours until 25 mm Hg is reached without bleeding; this pressure is generally maintained for the next 12-24 hours. If bleeding is controlled, deflate the esophageal balloon for 5 minutes every 6 hours to help prevent esophageal necrosis.

Once the tube is satisfactorily positioned, it is generally left in place for 24 hours. If bleeding recurs, the gastric balloon and, if necessary, the esophageal balloon may be reinflated for an additional 24 hours. However, in view of the high mortality among patients who rebleed, alternatives such as sclerotherapy and transjugular intrahepatic portacaval shunting (TIPS) should be considered.

Sengstaken Blakemore tube complications

Aspiration is probably the most frequent major complication of Sengstaken-Blakemore tube placement 15. The greatest risk of aspiration occurs during insertion. The risk of aspiration can be minimized by evacuating the stomach prior to tube placement and maintaining a low threshold for endotracheal intubation 16.

Asphyxiation is caused by proximal migration of the tube and can be prevented with endotracheal intubation 17. If tube migration results in airway obstruction, cutting across all the tube lumens just distal to the points of bifurcation allows immediate extraction of the entire tube.

Esophageal perforation or rupture can occur with inflation of a gastric balloon that is inadvertently placed in the esophagus or can be secondary to esophageal mucosal necrosis that results from excessive or prolonged inflation of the esophageal balloon 12.

Tracheal rupture can follow misplacement of the Sengstaken Blakemore tube in the trachea 18.

Minor complications include the following:

- Pain

- Pharyngeal and gastroesophageal erosions and ulcers caused by local pressure effects

- Pressure necrosis of the nose, lips, and tongue; rarely, pressure ulcers can develop over the facial skin where the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube is secured 19

- Hiccups.

- Gupta A, Pande Y. SENGSTAKEN – BLACKMORE TUBE. Med J Armed Forces India. 2001;57(2):148–149. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(01)80137-4 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4925856

- World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines. Esophageal Varices January 2014. https://www.worldgastroenterology.org/guidelines/global-guidelines/esophageal-varices/esophageal-varices-english

- Sengstaken RW, Blakemore AH. Balloon tamponage for the control of hemorrhage from esophageal varices. Ann Surg. 1950;131:781–789.

- Feneyrou B, Hanana J, Daures JP, Prioton JB. Initial control of bleeding from esophageal varices with the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube: experience in 82 patients. Am J Surg. 1988;155:509–511.

- Bosch J, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Garcia-Pagan JC. Portal hypertension and gastrointestinal bleeding. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:3–25.

- Choi JY, Jo YW, Lee SS, et al. Outcomes of patients treated with Sengstaken-Blakemore tube for uncontrolled variceal hemorrhage. Korean J Intern Med. 2018;33(4):696–704. doi:10.3904/kjim.2016.339 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6030415

- Nadler J, Stankovic N, Uber A, Holmberg MJ, Sanchez LD, Wolfe RE, et al. Outcomes in variceal hemorrhage following the use of a balloon tamponade device. Am J Emerg Med. 2017 Oct. 35 (10):1500-1502.

- de Franchis R, Baveno V Faculty Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762–768.

- Rajoriya N, Tripathi D. Historical overview and review of current day treatment in the management of acute variceal haemorrhage. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6481–6494.

- Carbonell N, Pauwels A, Serfaty L, Fourdan O, Levy VG, Poupon R. Improved survival after variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis over the past two decades. Hepatology. 2004;40:652–659.

- Colapinto RF, Stronell RD, Gildiner M, et al. Formation of intrahepatic portosystemic shunts using a balloon dilatation catheter: preliminary clinical experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;140:709–714.

- Choi JY, Jo YW, Lee SS, Kim WS, Oh HW, Kim CY, et al. Outcomes of patients treated with Sengstaken-Blakemore tube for uncontrolled variceal hemorrhage. Korean J Intern Med. 2018 Jul. 33 (4):696-704.

- Chen YI, Dorreen AP, Warshawsky PJ, Wyse JM. Sengstaken-Blakemore tube for non-variceal distal esophageal bleeding refractory to endoscopic treatment: a case report & review of the literature. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2014 Nov. 2 (4):313-5.

- Bensley RP, Mohr AM, Huber TS, Sappenfield JW. Novel use of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube during a neck exploration of a carotid injury: A case report. Injury. 2016 Sep. 47 (9):2048-50.

- Panés J, Terés J, Bosch J, Rodés J. Efficacy of balloon tamponade in treatment of bleeding gastric and esophageal varices. Results in 151 consecutive episodes. Dig Dis Sci. 1988 Apr. 33 (4):454-9.

- Edlich RF, Landé AJ, Goodale RL, Wangensteen OH. Prevention of aspiration pneumonia by continuous esophageal aspiration during esophagogastric tamponade and gastric cooling. Surgery. 1968 Aug. 64 (2):405-8.

- Collyer TC, Dawson SE, Earl D. Acute upper airway obstruction due to displacement of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008 Apr. 25 (4):341-2.

- Rosat A, Martín E. Tracheal rupture after misplacement of Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. Pan Afr Med J. 2016. 23:55.

- Kim SM, Ju RK, Lee JH, Jun YJ, Kim YJ. Unusual cause of a facial pressure ulcer: the helmet securing the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. J Wound Care. 2015 Jun. 24 (6 Suppl):S14-6.