What is calcium lactate?

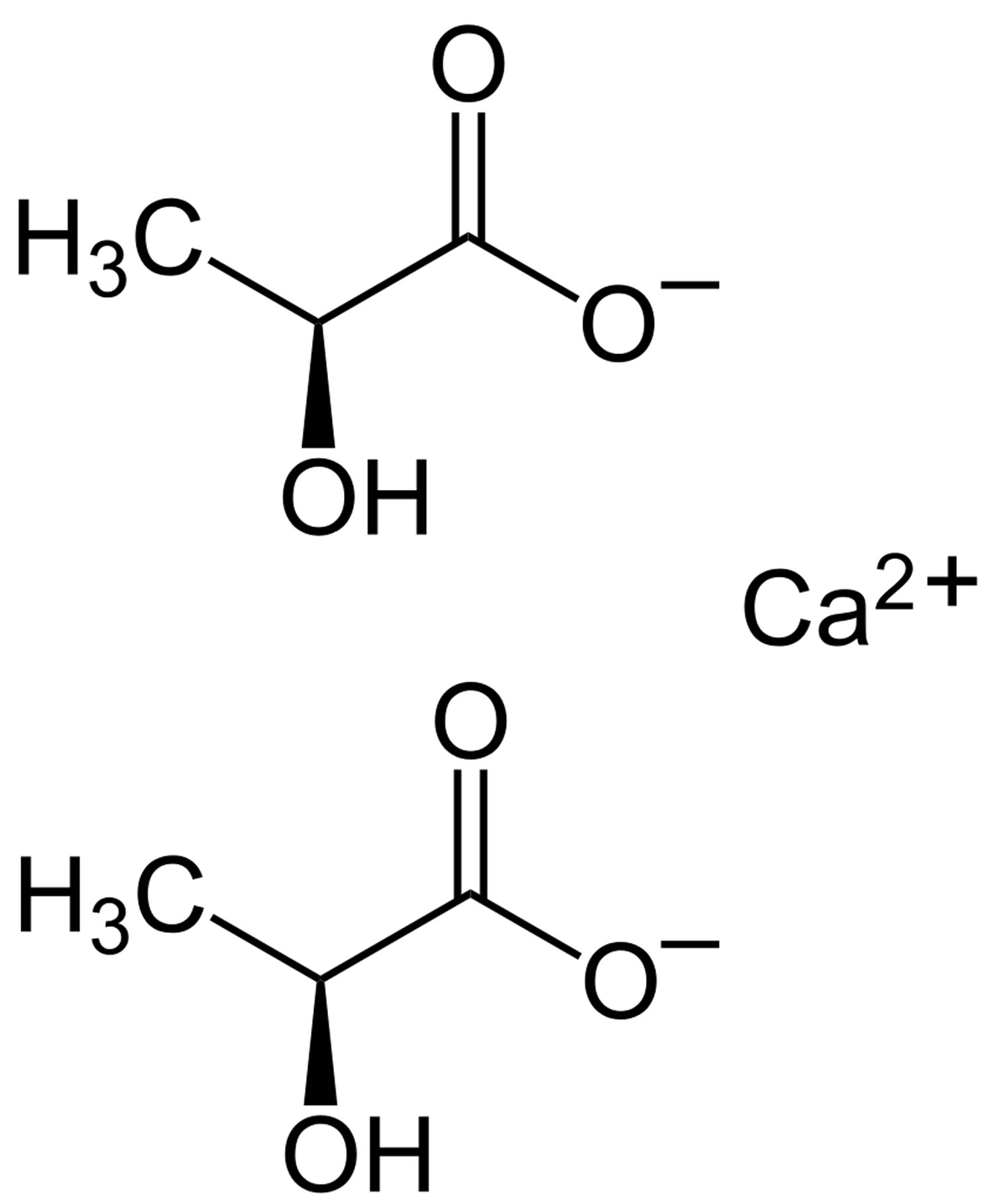

Calcium lactate (E 327) is a calcium salt of lactic acid (E270) that consists of two lactate anions for each calcium cation (Ca2+). Calcium lactate (E 327) is prepared commercially by the neutralization of lactic acid (a natural acid produced by bacteria in fermented foods) with calcium carbonate or calcium hydroxide 1. Approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a direct food substance affirmed as generally recognized as safe, calcium lactate is used as a firming agent, flavor enhancer, flavoring agent or adjuvant, leavening agent, stabilizer, and thickener in food with no limitations other than Good Manufacturing Practices 2, 3. Calcium lactate is also found in daily dietary supplements as a source of calcium. It is also available in various hydrate forms, where calcium lactate pentahydrate is the most common.

Lactic acid (E 270) and calcium lactate (E 327) are permitted food additives used in a variety of foods (e.g. nectars, jam, jellies, marmalades, mozzarella and whey cheese, fats of animal or vegetable origin for cooking and/or frying, canned and bottled fruits and vegetables, fresh pasta, beer) according to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 on food additives. Specifications for purity are laid down in Directive 2008/84/EC 1.

The Joint Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO) Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) issued an opinion on lactic acid and calcium lactate 4 allocating an acceptable daily intake (ADI) of ‘not limited’. In 1991, this acceptable daily intake (ADI) was supported by the Scientific Committee of Food (EC, 1991) and in 2006 iterated in the evaluation of lactate and sodium lactate for poultry carcass treatment 5.

For the U.S. population age 1 year and older, the per user mean and 90th percentile intakes of calcium lactate from the proposed use in the potato and vegetable snacks and sweetened crackers were 788 and 1,575 mg/day, respectively 3. This corresponds to calcium intakes of 114 and 228 mg/day, respectively, and lactate intake of 674 and 1,347 mg/day, respectively. For the U.S. population age 1 year and older, the per user mean and 90th percentile levels of intake of calcium from all sources, including background sources and the proposed uses, were estimated at 1,149 and 1,902 mg/day, respectively 3.

Maekawa et al. 6, conducted a two year drinking water study where calcium lactate was administered to F344 rats (50/sex/dose, randomized) for two years in the drinking water. Rats were administered 0, 2.5, or 5% levels in water, which was offered ad libitum, starting around 6 weeks of age. The study reported the group mean total intake of calcium lactate per rat, but did not translate this to a mg/kg body weight/day dose level, and likewise the European Chemicals Agency and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) did not report estimates of dose. The test substance was 97-101% pure. Following the two-year exposure period, rats were maintained in a recovery phase for nine weeks prior to terminal sacrifice. The study was published in 1991, and although a specific guideline was not followed, the study contains major features of modern guideline studies including body weight and clinical parameters, hematology, clinical chemistry, necropsy for gross findings, and histopathological assessment of representative tissues and all lesions. All rats that died during the study, and those surviving until termination, were subjected to a full necropsy. Body weights were measured once per week for the first 13 weeks, then every four weeks thereafter. Sample collections for hematology and clinical chemistry were obtained at terminal sacrifice following the recovery period. Animals were examined macroscopically and microscopically for gross lesions and neoplastic and non-neoplastic changes. The European Chemicals Agency summarized that there were no statistically significant treatment-related differences in terms of clinical signs or mortality between treated animals and controls, and there were no remarkable effects on hematology or clinical chemistry. The study authors, as well as European Chemicals Agency and Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), concluded that the study did not demonstrate carcinogenic potential for calcium lactate when administered via the drinking water for two years at the doses tested. Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) stated that the highest dose resulted in a significant reduction in body weight, which was approximately 13% as reported in the study by the authors 6. However, despite this finding of an approximately 13% decrease in body weight at the high dose, the study authors concluded that calcium lactate was neither toxic nor carcinogenic in F344 rats when given continuously through the drinking water for two years 6. Body weight changes are typically considered adverse if they are greater than approximately 10%, which could have led the study authors and others to conclude that the finding was non-adverse. The authors reported that there were no changes in clinical chemistry or hematology, and any organ weight changes observed were not found to be toxicologically significant and did not correlate with any histopathological alterations in those organs 6.

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has also reviewed lactic acid or salts of lactate within various EFSA Panels. It was evaluated as a flavoring in 2009 7, based on no safety concern at the current levels of intake and the role of lactic acid in health, normal mammalian metabolism. European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) 8 also had no concerns in a more recent review by their Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes, Flavourings, Processing Aids (CEF). Most recently, lactic acid and calcium lactate have been reviewed for use in animal food by EFSA’s Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in animal feed (FEEDAP) 9. In this application, EFSA considered that the proposed uses of lactic acid (lactate) were safe considering the endogenous nature of lactic acid, and that the proposed uses reviewed by the FEEDAP panel would not greatly alter the total intake from other food sources.

What is calcium lactate used for?

Calcium lactate is used as a firming agent, flavor enhancer, flavoring agent or adjuvant, leavening agent, stabilizer, and thickener in food with no limitations other than Good Manufacturing Practices 2, 3. Calcium lactate is also found in daily dietary supplements as a source of calcium. It is also available in various hydrate forms, where calcium lactate pentahydrate is the most common.

Sufficient calcium intake is achievable from a well-balanced diet. A wide array of natural calcium sources exist, including dairy products (e.g., milk, yogurt, cheese), vegetables (e.g., broccoli, kale), and foods fortified with calcium (e.g., fruit juices, cereals, and some grains).

The two primary oral forms of supplemental are calcium carbonate and calcium citrate 10. Calcium carbonate is cheaper and more commonly used. The absorption and bioavailabilities of these two compounds differ significantly. Calcium carbonate is dependent on the acidic environment of the stomach for adequate absorption and should be taken with food; Calcium citrate, however, has no such requirement 11. Studies have shown that calcium citrate has a significantly higher bioavailability than calcium carbonate 12. Of note, the absorption kinetics of orally administered calcium depends upon the absolute amount of calcium taken. As the dose of calcium increases, the percentage absorbed decreases 13. Other oral forms of calcium, although less widely used, include calcium phosphate, calcium lactate, and calcium gluconate 10.

The recommendations for dietary calcium intake are established by the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. They released the most current recommendations in 2010 and based on high-quality research studies and information from the decade prior 14. In summary, the Institute of Medicine committee performed a review of current literature pertaining to health outcomes of calcium and vitamin D intake. The determination was that these nutrients most certainly play an important role in bone health, but not necessarily in other health conditions. This committee released dietary reference intake (DRI) values, such as recommended dietary allowance (RDA) and estimated average requirement (EAR) measurements to serve as a guideline for appropriate calcium and vitamin D intake in healthy patients of different age groups 14. The recommended daily allowance (RDA) values are summarized below.

- 1 to 3 years old: 700 mg/daily

- 4 to 8 years old: 1,000 mg/daily

- 9 to 13 years old: 1,300 mg/daily

- 14 to 18 years old: 1,300 mg/daily

- 19 to 30 years old: 1,000 mg/daily

- 31 to 50 years old: 1,000 mg/daily

- 51 to 70-year-old males: 1,000 mg/daily

- 51 to 70-year-old females: 1,200 mg/daily

- Over 70 years old: 1200 mg/daily

- 14 to 18 years old (pregnant/lactating): 1,300 mg/daily

- 19 to 50 years old (pregnant/lactating): 1,000 mg/daily

The established upper limit of calcium intake is 2500 mg for adults aged 19 to 50 years, and 2000 mg for adults age 51 years and older 13. A recent study summarizing trends in calcium intake based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey determined that mean supplemental calcium intake reached a maximum in 2007 through 2008 and subsequently decreased 15. In 2013 and 2014, estimates were that 0.4% of the population had taken daily calcium at an amount higher than the tolerable upper intake level (UL). Supplemental calcium intake was greater among women, non-Hispanic whites, and adults older than 60 years of age 15.

The FDA acknowledges that an inadequate intake of calcium and/or vitamin D can contribute to low peak bone mass, which is an identifiable risk factor of osteoporosis. The official FDA statement is that “adequate calcium and vitamin D as part of a healthful diet, along with physical activity, may reduce the risk of osteoporosis in later life.” However, there is no specific discussion regarding calcium supplementation. The FDA does provide daily values (DV) on food products to educate consumers on the calcium content within the context of a recommended diet. The most recent daily value for calcium is 1,300 mg for adults and children older than 4 years of age.

Calcium supplementation is indicated when dietary calcium intake may be insufficient; the clinician can determine this by a patient’s dietary history. In general, obtaining calcium through a well-balanced diet is preferred to supplementation with other products. Other potential indications for calcium supplementation include osteoporosis, osteomalacia, hypocalcemic rickets, hypoparathyroidism, and hypocalcemia from chronic kidney disease (CKD).

The most common indication for calcium supplementation is to prevent or slow the progression of osteoporosis. Several randomized prospective clinical trials have demonstrated that daily calcium and vitamin D supplementation improves bone density in postmenopausal women and older men 16. However, different trials have yielded conflicting results regarding whether or not calcium and vitamin D supplementation decrease the risk of pathologic fractures 17. The suggestion is that differences in patient populations and demographics, specifically in living arrangements (community versus assisted-living), may have led to conflicting results. One of the largest and most-cited trials, the Women’s Health Initiative), determined that in healthy postmenopausal women, calcium and vitamin D supplementation led to a small but significant improvement in hip bone density, but no significant decrease in hip fracture 18.

When considering calcium supplementation, it is important to consider a patient’s renal function. Studies reveal that the majority of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) will not have symptomatic hypocalcemia, although certain medications like bisphosphonates and denosumab may increase this risk 19. In patients with severe chronic kidney disease (CKD), care should be given to ensure adequate serum calcium levels are maintained.

Excessive intake of calcium can result in harmful side effects. The Institute of Medicine of the National Academies has stated that calcium intake of 2000 milligrams or more daily increases the risk of harm and adverse events 13. The most common side effects of calcium supplements include gastrointestinal effects (e.g., constipation, dyspepsia, nausea, vomiting). The risk and severity of these side effects are improvable by taking calcium supplements with food. Another adverse event is an increased risk of nephrolithiasis in individual patients. Of note, high dietary calcium intake has not correlated with an increased incidence of kidney stones; However, oral calcium supplements have been shown to increase this risk. The cause of this paradoxical effect is still a topic of debate.

Another potential adverse event of excessive calcium intake, although controversial, is the worsening of underlying cardiovascular disease. Two separate meta-analyses demonstrated a potential marginal increased risk of myocardial infarction in patients receiving calcium supplementation versus controls. However, other studies and meta-analyses have yielded results that showed no association between calcium supplementation and risk of myocardial infarction. Currently, the National Osteoporosis Foundation has stated that “substantial evidence supports that taking the recommended amount of calcium supplements poses no risk to the heart.”

References- Safety of lactic acid and calcium lactate when used as technological additives for all animal species. EFSA Journal 2017;15(7):4938 https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.2903/j.efsa.2017.4938

- CFR – Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=184.1207&SearchTerm=calcium%20lactate

- GRAS Notification for the Use of Calcium Lactate in Potato and Vegetable Snacks and Sweetened Crackers. https://www.fda.gov/media/112854/download

- Calcium lactate. http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/jecfa_additives/docs/Monograph1/Additive-088.pdf

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority), 2008. Statement of the Scientific Panel of Food Additives, Flavourings,Processing Aids and Materials in Contact with Food on a request from the European Commission concerningthe use of lactic acid and sodium lactate and sodium lactate for poultry carcass decontamination. EFSA Journal2008;6(7):RN-234, 2 pp.https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2008.234r

- Maekawa A, Matsushima Y, Onoder H, Shibutani M, Yoshida J, Kodama Y, Kurokawa Y, Hayashi Y. 1991. Long-term toxicity/carcinogenicity study of calcium lactate in F344 rats. Fd Chem Toxic. 29(9):589-594.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). 2009. Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Food Additives, Flavourings, Processing Aids and Materials in Contact with Food (AFC). Flavouring Group Evaluation 64 (FGE.64): Consideration of aliphatic acyclic diols, triols, and related substances evaluated by JECFA (57th meeting) structurally related to aliphatic primary and secondary saturated and unsaturated alcohols, aldehydes, acetals, carboxylic acids and esters containing an additional oxygenated functional group and lactones from chemical groups 9, 13 and 30 evaluated by EFSA in FGE.10Rev1 (EFSA, 2008ab). The EFSA Joural (2009) ON-975, 1 of 50.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). 2011. EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes, Flavourings and Processing Aids (CEF); Scientific Opinion on Flavouring Group Evaluation 96 (FGE.96): Consideration of 88 flavouring substances considered by EFSA for which EU production volumes / anticipated production volumes have been submitted on request by DG SANCO. EFSA Journal 2011; 9(12):1924. [60 pp.]. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.1924

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). 2015. EFSA FEEDAP Panel (EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed), Scientific opinion on the safety and efficacy of lactic acid and calcium lactate when used as technological additives for all animal species. EFSA Journal 2015;13(12):4198, 19 pp. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4198

- Straub DA. Calcium supplementation in clinical practice: a review of forms, doses, and indications. Nutr Clin Pract. 2007 Jun;22(3):286-96.

- Wood RJ, Serfaty-Lacrosniere C. Gastric acidity, atrophic gastritis, and calcium absorption. Nutr. Rev. 1992 Feb;50(2):33-40.

- Sakhaee K, Bhuket T, Adams-Huet B, Rao DS. Meta-analysis of calcium bioavailability: a comparison of calcium citrate with calcium carbonate. Am J Ther. 1999 Nov;6(6):313-21

- Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Gallagher JC, Gallo RL, Jones G, Kovacs CS, Mayne ST, Rosen CJ, Shapses SA. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011 Jan;96(1):53-8.

- Aloia JF. Clinical Review: The 2011 report on dietary reference intake for vitamin D: where do we go from here? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011 Oct;96(10):2987-96.

- Rooney MR, Michos ED, Hootman KC, Harnack L, Lutsey PL. Trends in calcium supplementation, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999-2014. Bone. 2018 Jun;111:23-27.

- Zhu K, Bruce D, Austin N, Devine A, Ebeling PR, Prince RL. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of calcium with or without vitamin D on bone structure and bone-related chemistry in elderly women with vitamin D insufficiency. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008 Aug;23(8):1343-8.

- Porthouse J, Cockayne S, King C, Saxon L, Steele E, Aspray T, Baverstock M, Birks Y, Dumville J, Francis R, Iglesias C, Puffer S, Sutcliffe A, Watt I, Torgerson DJ. Randomised controlled trial of calcium and supplementation with cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) for prevention of fractures in primary care. BMJ. 2005 Apr 30;330(7498):1003.

- Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, Wallace RB, Robbins J, Lewis CE, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black HR, Blanchette P, Bonds DE, Brunner RL, Brzyski RG, Caan B, Cauley JA, Chlebowski RT, Cummings SR, Granek I, Hays J, Heiss G, Hendrix SL, Howard BV, Hsia J, Hubbell FA, Johnson KC, Judd H, Kotchen JM, Kuller LH, Langer RD, Lasser NL, Limacher MC, Ludlam S, Manson JE, Margolis KL, McGowan J, Ockene JK, O’Sullivan MJ, Phillips L, Prentice RL, Sarto GE, Stefanick ML, Van Horn L, Wactawski-Wende J, Whitlock E, Anderson GL, Assaf AR, Barad D., Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006 Feb 16;354(7):669-83.

- McCormick BB, Davis J, Burns KD. Severe hypocalcemia following denosumab injection in a hemodialysis patient. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2012 Oct;60(4):626-8.