Venous leak

Venous leak also called venogenic erectile dysfunction, corporal veno-occlusive dysfunction, cavernosal dysfunction or penile venous insufficiency, which is an inability to maintain a penile erection to perform satisfactory sexual activity, is a type of vasculogenic impotence in the presence of sufficient arterial blood flow through the cavernosal arteries of the penis 1. In venous leak, the penis can’t store blood during an erection, meaning that the man can’t keep an erection because blood doesn’t stay trapped in the penis long enough. Venous leak can happen at any age. Failure of adequate venous occlusion has been proposed as one of the most common causes of venogenic impotence 2. The cause of venous leakage or veno-occlusive dysfunction is not exactly known 3. Venous leak may result from several possible pathophysiologic processes which include the presence of large venous channels draining the corpora cavernosa, Peyronie’s disease, diabetes and structural alterations in the fibroelastic components of the trabeculae, cavernous smooth muscle and endothelium 4. Furthermore, increasing age, diabetes mellitus, pelvic radiation, androgen deprivation therapy, and radical prostatectomy are linked to venogenic venous leak or venogenic erectile dysfunction 5.

Although the exact prevalence of this disease in the male population is still not completely known, many studies have been conducted, with the Massachusetts Male Aging Study being the first large-scale community-based study of this pathology. This study reported the prevalence of erectile dysfunction to be 2.6% 6. Another study reported the prevalence to be 52% among non-institutionalized males aged between 40 years and 70 years 7.

In patients having erectile dysfunction, it is important to differentiate a neurological or psychological cause from an organic cause. In addition to a comprehensive clinical history, physical examination, and appropriate laboratory investigations, color Doppler ultrasonography of the penis has become valuable in the evaluation of erectile dysfunction. It is a relatively inexpensive and minimally invasive tool that allows a good view of the penile anatomy 8, as well as the flow patterns in the vessels, in the diagnosis of erectile dysfunction 9.

Currently, no standardized method is available to accurately and systematically diagnose venous leak or corporal veno-occlusive dysfunction independently of general arterial insufficiency 10. Most medical experts and organizations think that venous leak is a consequence rather than an isolated cause of erectile dysfunction 11. As such, both the American Urological Association and the International Society for Sexual Medicine concur that “surgeries or penile veins ligation performed with the intent to limit the venous outflow of the penis are not recommended” 12. It seems that this treatment modality deal with a secondary effect rather than the primary causal factor of the venous leak or venogenic erectile dysfunction; therefore the results of treatment are unsatisfactory 13.

Recently, an interventional approach to restore sufficient penile erection using selective embolization of insufficient veins have been clinically studied as an alternative to invasive surgical treatment 5. Success of the interventional approach makes this procedure an attractive treatment option, as it is less invasive and more cosmetically pleasing than surgical approach 5.

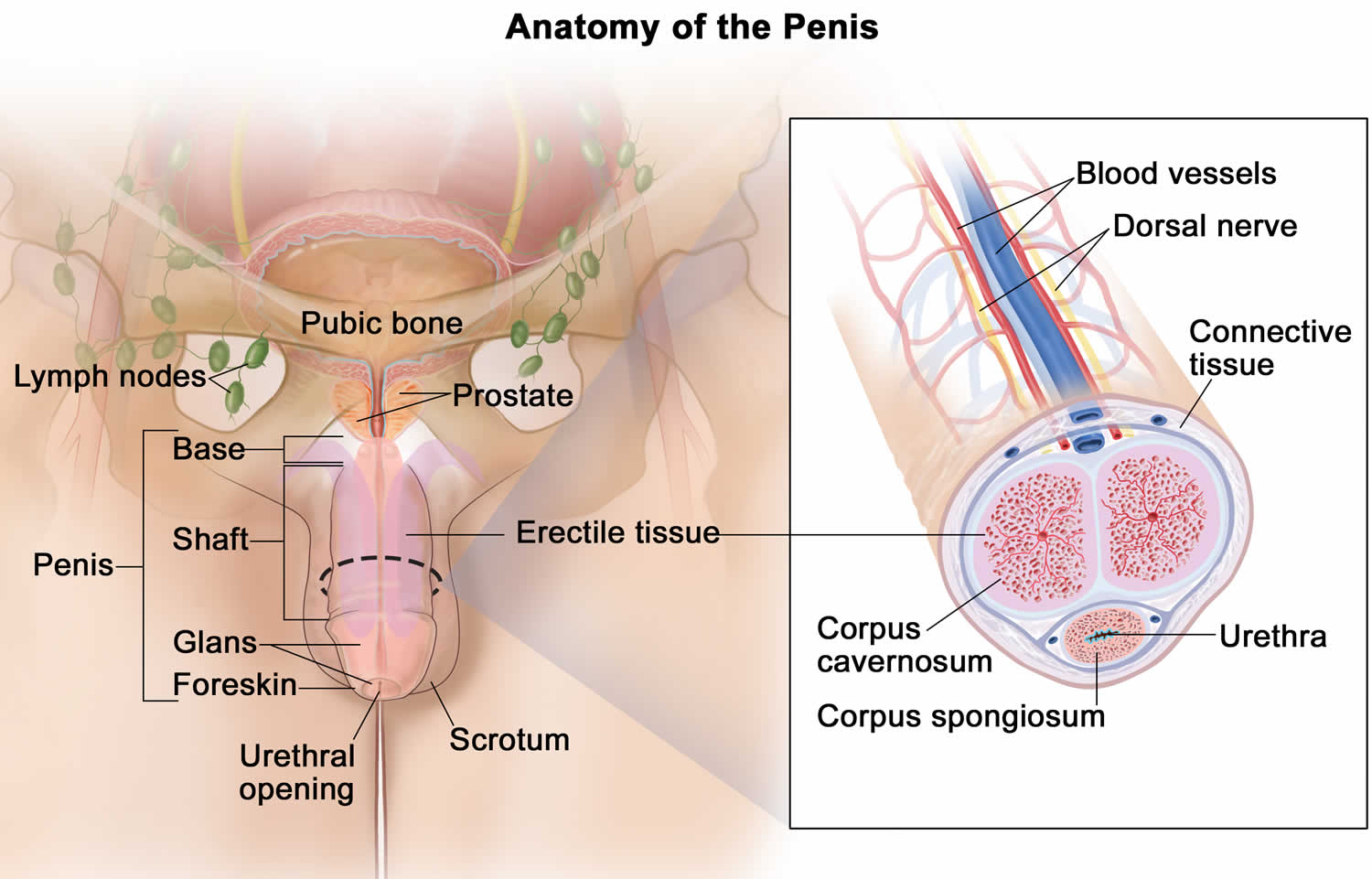

Figure 1. Penis anatomy

Venous leak causes

The cause of venous leak or venogenic erectile dysfunction is not exactly known. Various pathologic processes were accused but none proved entirely satisfactory. These include presence of large venous channels draining corpora cavernosa, Peyronie’s disease, diabetes and structural alterations in fibroblastic components of trabeculae and cavernous smooth muscles 3. Furthermore, increasing age, diabetes mellitus, pelvic radiation, androgen deprivation therapy, and radical prostatectomy are linked to venogenic venous leak or venogenic erectile dysfunction 5.

Venous leak or venogenic erectile dysfunction is considered to result from an improperly functioning occlusion mechanism 14. Investigations lay stress on the role of the tunica albuginea in the venous occlusion mechanism of the penis during erection 15. In this study 3, the tunica albuginea collagen was found degenerated and atrophic and this probably leads to subluxation and floppiness of the tunica albuginea as a tube surrounding the penile corporal tissue. It appears that the subluxated tunica albuginea, during erection, fails to effect compression of both the subtunical venular plexus and the emissary veins passing through it. Failure of occlusion of the penile venous outflow presumably leads to venous leakage during erection and seems to explain the erectile dysfunction in these patients 3.

Furthermore, under normal physiologic conditions, the tunica albuginea is responsible for morphologically shaping the penis during erection. The collagenous structure gives the tunica albuginea a textile nature which firmly supports the penile architecture during penile tumescence. This tunica albuginea textile nature, with its circularly and longitudinally oriented collagen fibers lends the tunica albuginea an adaptability to adjust its length and breadth according to the penile status, whether flaccid or erected. Due to their inelasticity, the collagen fibers limit excessive tunical stretch during penile tumescence. This mechanism prevents tunical subluxation and floppiness which may result from repeated penile tumescence which occurs during the sexual life. Meanwhile, an atrophic subluxated tunica albuginea would not only disrupt the “venous-leak proof” effect of the tunica albuginea but disturb the solidity of the erected penis during the process of vaginal penetration and thrusting.

It may be argued that the tunica albuginea changes are the result of venous leakage. However, this does not seem to be the case since the tunica albuginea rigidity is claimed to act for prevention of venous lelakage during erection 15. Therefore, although it appears inappropriate that venous leakage should lead to tunical subluxation and floppiness, this possibility cannot be excluded.

Investigators reported a significant decrease in elastic fibers in the tunica albuginea of impotent patients in comparison to a control group 16. A reduction of the tunica albuginea elastic fibers is likely to produce disorders in the arrangement of collagen fibers 17. As a matter of fact, electron microscopy revealed severe myopathic, fibrotic changes in the penile tissue 18.

The possible cause of the atrophic subluxated tunica albuginea needs to be discussed. The tunica albuginea consists of collagen and thus may be involved in the pathology of collagen diseases. However, none of the patients had any of these conditions. Aging may affect the tunica albuginea integrity, but the studied subjects were middle-aged. The history and investigative results of the patients have shown that they had no relevant pathological conditions nor were under drug regimens that may cause erectile dysfunction. However, a recent study has shown that androgen administered to patients with erectile dysfunction due to venous leak has improved erection in some, but not in all patients 19. The investigators suggested that penile tissue remodeling is the mechanism that is presumably responsible for correction of the venous leak by androgen treatment. In view of these factual aspects, scientists hypothesize that collagenous degeneration and atrophy could be a primary pathologic condition affecting the tunica albuginea 3.

Lifestyle factors and diabetes

Alcohol and smoking habits have consistently been shown to affect erectile function. Evidence from observational studies suggests a positive dose–response association between quantity and duration of smoking and the risk of erectile dysfunction 20. Similar results have been documented for alcohol abuse 21. In addition, diets that are low in whole-grain foods, legumes, vegetables and fruits, and high in red meat, full-fat dairy products, and sugary foods and beverages are all associated with an increased risk of erectile dysfunction 22. Finally, meta-analysis of available evidence demonstrates that moderate and more frequent physical activity are associated with reduced risk of erectile dysfunction 23. Accordingly, both cross-sectional and prospective epidemiological studies suggest that obesity and metabolic syndrome are associated with an increased risk of erectile dysfunction 24. It is conceivable that obesity-associated hypogonadism and increased cardiovascular risk are correlated with the higher prevalence of erectile dysfunction in overweight and obese men. However, recent clinical and experimental studies suggest that the association between erectile dysfunction and central obesity is independent from obesity-associated comorbidities and hypogonadism 24. Although increased levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF; also known as TNFα) — a cytokine involved in systemic inflammation — could be a mediator of these conditions 25, further studies are needed to confirm this. Sexual health is impaired by type 1 and type 2 diabetes and even by a pre-diabetic status 26. Peripheral neuropathy, atherosclerosis of large blood vessels, endothelial dysfunction of arterioles and the associated hypogonadism all contribute to diabetes-related sexual dysfunction 27.

Cardiovascular disease

Arteriogenic erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease are considered different manifestations of a common underlying vascular disorder. Three independent meta-analyses have documented that erectile dysfunction needs to be considered the harbinger of coronary heart disease 28 and as a predictor of future silent cardiac events 29. This association is particularly important in younger men (<55 years of age) and those with erectile dysfunction and no other comorbidites 28, emphasizing the importance of early diagnosis and correct management of erectile dysfunction-associated morbidities. Accordingly, the Princeton III Consensus Recommendations for the management of erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease indicate that incident erectile dysfunction has a similar, or even greater, predictive value for cardiovascular disease than traditional risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia or smoking 30.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms

The presence of lower urinary tract symptoms alongside benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) represents another important issue in men with erectile dysfunction. The Multinational Survey of The Ageing Male (MSAM-7) study — a multinational survey conducted in the United States and six European countries — demonstrated that the presence of lower urinary tract symptoms is an independent risk factor for erectile dysfunction, although the pathological reason for this association is unclear 31. Common alterations in the NO–cGMP pathway, enhancement of RHOA–ROCK signalling and pelvic atherosclerosis are often considered the most important mechanisms involved in determining the two conditions.

Psychogenic and relationship factors

Aside from organic factors, psychogenic and relationship domains need to be evaluated in men with symptoms of erectile dysfunction. All sexual dysfunctions, even the most documented organic types (such as diabetes-associated erectile dysfunction), are stressful and can lead to psychological disturbances 32. Performance anxiety is a common issue in men with sexual dysfunction, often leading to avoidance of sex, loss of self-esteem and depression 32. Psychiatric symptoms are often comorbid in patients with erectile dysfunction 32. In addition, many psychotropic drugs can induce erectile and other sexual problems 32.

Although considered less often, the quality of a relationship represents an essential determinant of successful sexual activity. In fact, any sexual dysfunction in one member of the couple will affect the couple as a whole, causing distress, partner issues and further exacerbation of the original sexual problem 33. Interestingly, a patient’s perception of reduced partner interest represents an independent predictor of incident cardiovascular events 34. Hence, the physical relationship between partners should be considered not only as enjoyable, but also as a strategy for improving overall health and life expectancy.

Venous leak symptoms

Venous leak an inability to maintain a penile erection to perform satisfactory sexual activity in the presence of sufficient arterial blood flow through the cavernosal arteries of the penis 1. In venous leak, the penis can’t store blood during an erection, meaning that the man can’t keep an erection because blood doesn’t stay trapped in the penis long enough.

Venous leak diagnosis

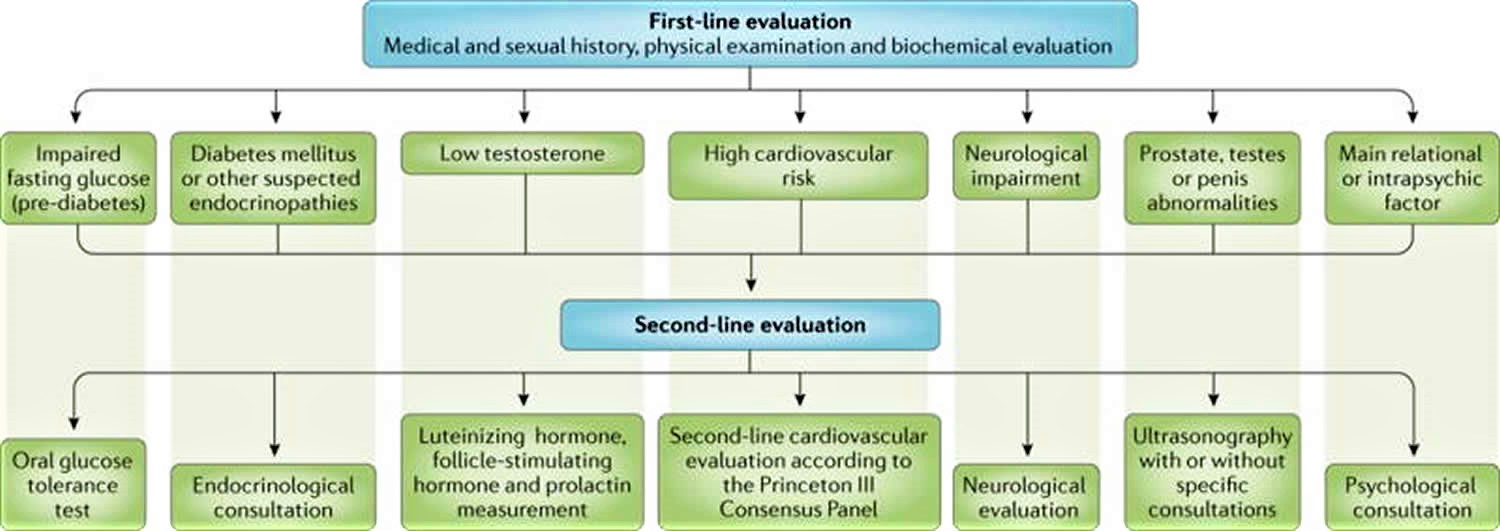

The identification of the pathogenetic factors involved in erectile dysfunction is the cornerstone of an accurate diagnosis and successful treatment 11. The basic work-up of patients seeking medical care for erectile dysfunction should include an accurate medical and sexual history, a careful general and andrological physical examination, hormonal evaluation (total testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin in all men, prolactin and thyroid hormone evaluation in some men) and routine biochemical exams (total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose and glycosylated haemoglobin). Second-line evaluation should be limited to those with abnormal first-line results.

Diagnostic work-up

The basic work-up of patients seeking medical care for erectile dysfunction needs to include an evaluation of all the aforementioned factors, including: establishing an accurate medical and sexual history; a careful general and focused genitourinary examination; and a minimum number of hormonal and routine biochemical tests (Figure 2). Other optional tests can be considered in specific situations (see below).

Figure 2. Diagnostic work-up for patients with erectile dysfunction

The physical examination of patients includes evaluation of the chest (including heart rhythm, breathing and signs of gynaecomastia [enlargement of the breasts]), penis, prostate and testes, and of the distribution of body hair 35. Small testes and/or small prostate volume, according to the patient’s age, might imply underlying hypogonadism. Similarly, other possible signs of hypogonadism include gynaecomastia as well as a decrease in beard and body hair growth. Assessment of the peripheral vascular system is also important to determine the characteristics of the pulse, to ascertain the presence of an arterial bruit (a vascular sound that is associated with turbulent blood flow). Increased pulse rate (tachycardia) might suggest hyperthyroidism, whereas reduced pulse rate (bradycardia) might be evident in men with heart block (arrhythmia), hypothyroidism or in those who use certain drugs (for example, β-blockers). Diminished or absent pulses in the various arteries examined could be indicative of impaired blood flow caused by atherosclerosis. The evaluation of the penis in the flaccid condition might show the presence of Peyronie disease (involving palpable fibrous plaques), phimosis (congenital narrowing of the opening of the foreskin) or frenulum breve (whereby the tissue under the glans penis that connects to the foreskin is too short and restricts the movement of the foreskin), which can all contribute to erectile dysfunction. Measurement of blood pressure, waist circumference and body mass index is also performed 35.

A few biochemical and hormonal parameters are of value in patients with erectile dysfunction. However, levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose and glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) are important determinants of cardiovascular and metabolic risk stratification 36. Total testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin for the evaluation of calculated free testosterone 36 are sufficient parameters to rule out hypogonadism. Prolactin and thyroid hormone evaluation are limited to a subset of patients 36.

The vast majority of men with erectile dysfunction are managed within the primary care setting. However, in the presence of abnormal biochemical or hormonal values, further diagnostic tests are advisable (second-line evaluation). If the fasting plasma glucose level is 100–126 mg dl−1, or HbA1c is >5.7%, an oral glucose tolerance test can be used to exclude overt type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The necessity of performing further cardiovascular evaluation should be based on the criteria of the Princeton 3 Consensus Panel (Table 1) 30. In the presence of reduced total testosterone and/or calculated free testosterone, obtaining prolactin and gonadotropin levels will determine the source (central or peripheral) of the problem.

Recent data have documented that penile duplex Doppler ultrasound (PDDU) can be performed in both flaccid (before vasodilator stimulation) and dynamic states (after vasodilator stimulation) to further improve the stratification of cardiovascular risk in men with erectile dysfunction 37. Nocturnal penile tumescence and rigidity testing using the RigiScan device (GOTOP Medical, USA) is currently rarely carried out 38; its use is limited to testing the presence of nocturnal spontaneous erectile activity for medico-legal purposes when the presence of naturally occurring erections needs to be demonstrated. Arteriography and dynamic infusion cavernosometry (measuring cavernosal blood pressure) and cavernosography (to assess venous leak) are carried out only in young men who are potential candidates for vascular reconstructive surgery 38.

Table 1. Princeton 3 Consensus recommendations

| Profile | Description | Sexual activity and PDE5 inhibitor (phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor) use |

|---|---|---|

| Low |

|

|

| Intermediate |

|

|

| High |

| Sexual activity delayed until cardiac condition stabilized |

Footnote: Princeton 3 Consensus recommendations for risk stratification and cardiovascular evaluation for sexual activity.

* Major cardiovascular risk factors include age, male gender, hypertension, type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus, smoking, dyslipidaemia, a sedentary lifestyle and a family history of premature cardiovascular disease.

‡ Defined by the Canadian Cardiovascular Society 39.

[Source 30 ]Venous leak treatment

Treatment with oral phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (initially sildenafil, and later, vardenafil, tadalafil, avanafil, and others available outside of the United States) is usually of minimal effective 5. Prostaglandin intracavernosal injection therapy involves the use of vasoactive substances injected directly into the corpora cavernosa via a small needle 11. These vasoactive agents include prostaglandin E1, papaverine and phentolamine (and sometimes atropine), which work alone or in combination to elicit an erection. Prostaglandin E1 has been approved by the FDA as a single-agent intracavernosal injection for erectile dysfunction and increases cAMP levels. Papaverine is a nonspecific phosphodiesterase inhibitor that leads to increased levels of cAMP and cGMP. Phentolamine is an α1-adrenergic receptor inhibitor that helps to prevent vasoconstriction to maintain tumescence 40. These vasoactive drugs are available in varying strengths and combinations made by pharmacies: monotherapy with prostaglandin E1; bi-mixture of papaverine and phentolamine; and tri-mixture of prostaglandin E1, papaverine and phentolamine. Patients require training on how to prepare the medications with syringes for home use; an in-office test dose can be useful to characterize the patient’s response. The dose can then be titrated up or down under supervision to one that is satisfactory to the patient. Many patients have an understandable fear of injecting the penis, and overcoming this is the first step to successful treatment 41. Prostaglandin intracavernosal injection therapy demonstrates a better outcome initially, but it requires continuous use and often loses its efficacy over time 5. Therefore, a more long-term solution is needed. Besides injectable medications, conventional treatments of venogenic erectile dysfunction consist of penile constrictor rings, penile vacuum pumps, penile prostheses, and ligation of the deep dorsal vein of the penis 5. Recently, an interventional approach using selective embolization of veins implicated in venous insufficiency has been clinically studied as an alternative for conventional venogenic erectile dysfunction treatments 42. It offers more long-term efficacy compared with nonsurgical treatments and is less invasive and more cosmetically pleasing than surgical option 5. The clinical study performed by Rebonato et al 5 consisted of 18 patients with moderate to severe venogenic erectile dysfunction with significant improvement for 16 patients, out of which 7 patients no longer suffered from erectile dysfunction at the end of follow-up. The medical history of patients is not described. In this case study 43, the patient suffered from full impotence even with medication and a history of radical prostectomy before the onset of venogenic erectile dysfunction. This procedure allowed the patient to have full penile erection supplemented by stimulation and impotence medication. This case gives credence to the safety and high efficacy of this procedure for severe form of venogenic erectile dysfunction with a history of radical prostectomy. Future patients who develop complete impotence due to venous leakage after radical prostectomy may greatly benefit from this mostly unused percutaneous procedure and additionally benefit from minimally invasive and thus also cosmetically pleasing nature of this technique.

References- Rogers, R., Graziottin, T., Lin, C. et al. Intracavernosal vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injection and adeno-associated virus-mediated VEGF gene therapy prevent and reverse venogenic erectile dysfunction in rats. Int J Impot Res 15, 26–37 (2003) doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3900943 https://www.nature.com/articles/3900943

- Rajfer J, Rosciszewski A, Mehringer M. Prevalence of corporal venous leakage in impotent men. J Urol. 1988;140:69–71 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(17)41489-3

- Shafik A, Shafik I, El Sibai O, Shafik AA. On the pathogenesis of penile venous leakage: role of the tunica albuginea. BMC Urol. 2007;7:14. Published 2007 Sep 5. doi:10.1186/1471-2490-7-14 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1995196

- Iacono F, Barra S, DeRosa G, et al. Microstructural disorders of tunica albuginea in patients affected by Peyronies’s disease with or without erection dysfunction. J Urol. 1993;150:1806–1809.

- Rebonato A., Auci A., Sanguinetti F., Maiettini D., Rossi M., Brunese L. Embolization of the periprostatic venous plexus for erectile dysfunction resulting from venous leakage. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:866–872.

- Johannes CB, Araujo AB, Feldman HA, Derby CA, Kleinman KP, McKinlay JB. Incidence of erectile dysfunction in men 40 to 69 years old: longitudinal results from the Massachusetts male aging study. J Urol. 2000;163:460–463.

- Araujo AB, Travison TG, Ganz P, Chiu GR, Kupelian V, Rosen RC, et al. Erectile dysfunction and mortality. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2445–2454.

- Smith JF, Brant WO, Fradet V, Shindel AW, Vittinghoff E, Chi T, et al. Penile sonographic and clinical characteristics in men with Peyronie’s disease. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2858–2867.

- Golubinski AJ, Sikorski A. Usefulness of power Doppler ultrasonography in evaluating erectile dysfunction. BJU Int. 2002;89:779–782.

- Sohn M, Martin-Morales A. In: Surgical Treatment of Erectile Dysfunction. Porst JB, editor. 2006.

- Yafi FA, Jenkins L, Albersen M, et al. Erectile dysfunction. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16003. Published 2016 Feb 4. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.3 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5027992

- Montague DK, et al. Chapter 1: the management of erectile dysfunction: an AUA update. J Urol. 2005;174:230–239.

- Lewis R. Surgery for erectile dysfunction. In: Walsh PC, Retik AB, Vaughan ED, Wein AJ, editor. Campbell’s Urology. 7. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; pp. 1215–1235.

- Fitzpatrick TJ. Penile intercommunicating venous valvular system. J Urol. 1982;127:1099–1100.

- Montague DK, Lakin MM. False diagnosis of venous leakimpotence. J Urol. 1992;148:148–149.

- Iacono F, Barra S, de Rosa G, Boscaino A, Lotti T. Microstructural disorders of tunica albuginea in patients affected by impotence. Eur Urol. 1994;26:233–239.

- Akkus E, Carrier S, Baba K, Hsu GL, Padma-Nathan H, Nunes L, Lue TF. Structural alterations in the tunica albuginea of the penis: impact of Peyronie’s disease, ageing nd impotence. Br J Urol. 1997;80:190.

- Liu LC, Huang CH, Huang YL, Chiang CP, Chou YH, Liu LH, Shieh SR, Lu PS. Ultrastructural features of penile tissue in impotent men. Br J Urol. 1993;72:635–642.

- Yassin AA, Saad F, Traish A. Testosterone undecaonoate restores erectile function in a subset of patients with venous leakage: a series of case reports. J Sex Med. 2006;3:727–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00267.x

- Corona G, et al. Psychobiological correlates of smoking in patients with erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:527–534.

- Boddi V, et al. Priapus is happier with Venus than with Bacchus. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2831–2841.

- Wang F, Dai S, Wang M, Morrison H. Erectile dysfunction and fruit/vegetable consumption among diabetic Canadian men. Urology. 2013;82:1330–1335.

- Cheng JY, Ng EM, Ko JS, Chen RY. Physical activity and erectile dysfunction: meta-analysis of population-based studies. Int J Impot Res. 2007;19:245–252.

- Corona G, et al. Erectile dysfunction and central obesity: an Italian perspective. Asian J Androl. 2014;16:581–591.

- Vignozzi L, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis as a novel player in metabolic syndrome-induced erectile dysfunction: an experimental study in the rabbit. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;384:143–154.

- Corona G, et al. The SUBITO-DE study: sexual dysfunction in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes male patients. J Endocrinol Invest. 2013;36:864–868.

- Corona G, et al. Sexual dysfunction at the onset of type 2 diabetes: the interplay of depression, hormonal and cardiovascular factors. J Sex Med. 2014;11:2065–2073.

- Vlachopoulos CV, Terentes-Printzios DG, Ioakeimidis NK, Aznaouridis KA, Stefanadis CI. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with erectile dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:99–109.

- Yamada T, Hara K, Umematsu H, Suzuki R, Kadowaki T. Erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular events in diabetic men: a meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e4367.

- Nehra A, et al. The Princeton III Consensus recommendations for the management of erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:766–778. This manuscript details how erectile dysfunction is an early symptom of cardiovascular disease.

- Rosen R, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms and male sexual dysfunction: the multinational survey of the aging male (MSAM-7) Eur Urol. 2003;44:637–649. This publication describes the relationship of LUTS and erectile dysfunction.

- Jannini EA, McCabe MP, Salonia A, Montorsi F, Sachs BD. Organic versus psychogenic? The Manichean diagnosis in sexual medicine. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1726–1733.

- Corona G, et al. Impairment of couple relationship in male patients with sexual dysfunction is associated with overt hypogonadism. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2591–2600.

- Corona G, et al. Male sexuality and cardiovascular risk A cohort study in patients with erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1918–1927.

- Ghanem HM, Salonia A, Martin-Morales A. SOP: physical examination and laboratory testing for men with erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2013;10:108–110.

- Buvat J, Maggi M, Guay A, Torres LO. Testosterone deficiency in men: systematic review and standard operating procedures for diagnosis and treatment. J Sex Med. 2013;10:245–284. A detailed review of testosterone deficiency, including current management modalities.

- Rastrelli G, et al. Flaccid penile acceleration as a marker of cardiovascular risk in men without classical risk factors. J Sex Med. 2014;11:173–186.

- Sikka SC, Hellstrom WJ, Brock G, Morales AM. Standardization of vascular assessment of erectile dysfunction: standard operating procedures for duplex ultrasound. J Sex Med. 2013;10:120–129.

- Campeau L. Grading of angina pectoria. Circulation. 1976;54:522–523.

- Virag R, Shoukry K, Floresco J, Nollet F, Greco E. Intracavernous self-injection of vasoactive drugs in the treatment of impotence: 8-year experience with 615 cases. J Urol. 1991;145:287–292. discussion 292–293.

- Nelson CJ, et al. Injection anxiety and pain in men using intracavernosal injection therapy after radical pelvic surgery. J Sex Med. 2013;10:2559–2565.

- Beradinucci D., Morales A., Heaton J.P.W., Fenemore J., Bloom S. Surgical treatment of penile veno-occlusive dysfunction: is it justified? Urology. 1996;47(1):88–92.

- Lee D, Rotem E, Lewis R, Veean S, Rao A, Ulbrandt A. Bilateral external and internal pudendal veins embolization treatment for venogenic erectile dysfunction. Radiol Case Rep. 2016;12(1):92–96. Published 2016 Dec 22. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2016.11.002 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5310371