Skin cancer in children

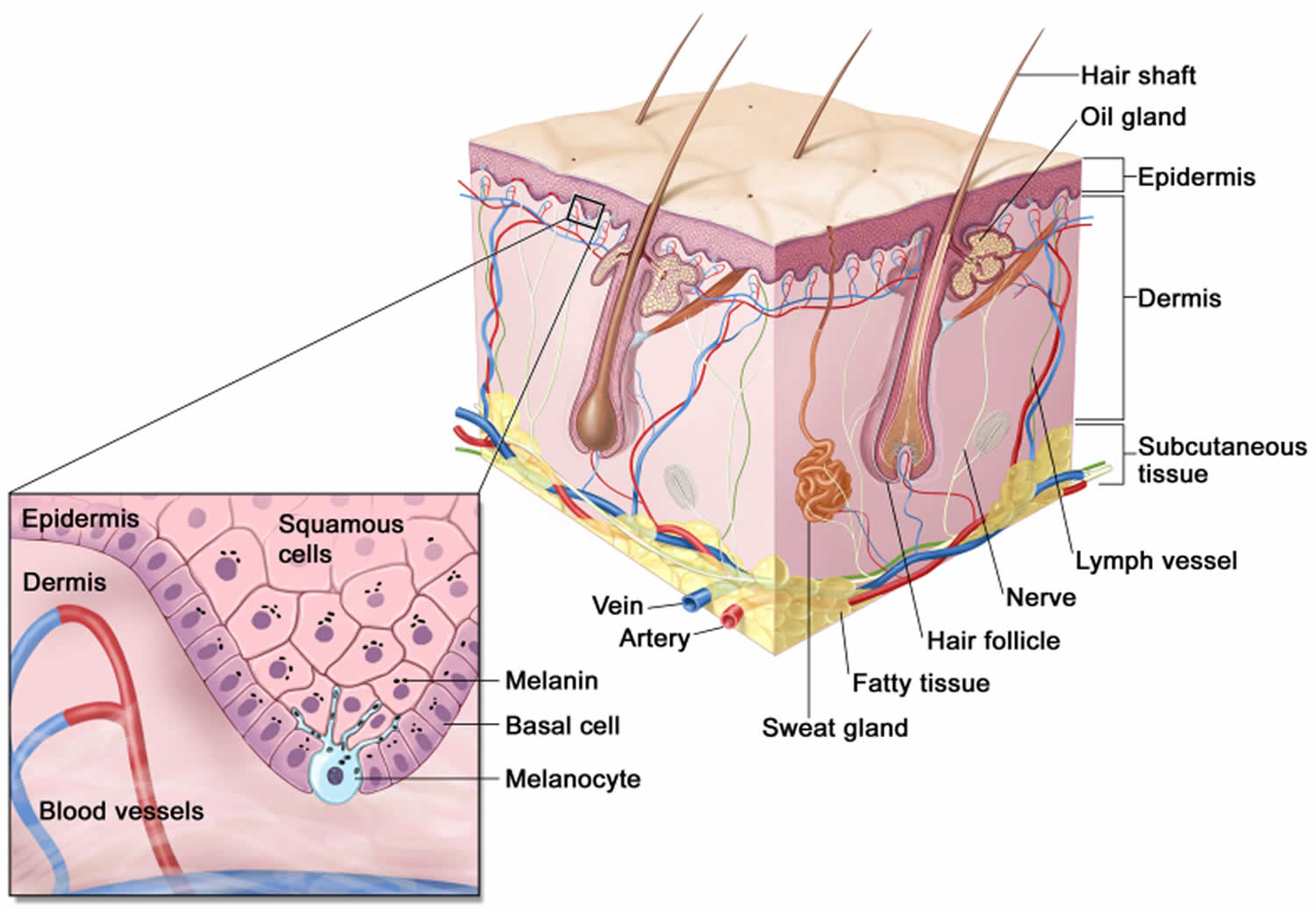

Skin cancer is very rare in children. Skin cancer is a type of cancer that grows in the cells of the skin. Skin cancer can spread to and damage nearby tissue and spread to other parts of the body.

There are 3 main types of skin cancer:

- Basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The majority of skin cancers are basal cell carcinoma. It’s a very treatable cancer. It starts in the basal cell layer of the skin (epidermis) and grows very slowly. The cancer usually appears as a small, shiny bump or nodule on the skin. It occurs mainly on areas exposed to the sun, such as the head, neck, arms, hands, and face. It more often occurs among people with light-colored eyes, hair, and skin.

- Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). This cancer is less common. It grows faster than basal cell carcinoma, but it’s also very treatable. Squamous cell carcinoma may appear as nodules or red, scaly patches of skin, and may be found on the face, ears, lips, and mouth. It can spread to other parts of the body, but this is rare. This type of skin cancer is most often found in people with light skin.

- Melanoma. This type of skin cancer is a small portion of all skin cancers, but it causes the most deaths. It starts in the melanocyte cells that make pigment in the skin. It may begin as a mole that turns into cancer. This cancer may spread quickly. Melanoma most often appears on fair-skinned people, but is found in people of all skin types.

The term non-melanoma skin cancer refers to all types of skin cancer apart from melanoma. BCC and SCC are also called keratinocyte cancer.

Each subtype of skin cancer has unique characteristics.

Skin cancer most commonly affects older adults. Your risk goes up as you get older.

Skin cancer in children key points:

- Skin cancer is rare in children.

- Skin cancer is more common in people with light skin, light-colored eyes, and blond or red hair.

- Bring your child to see a doctor if you see any unusual changes in your child’s skin.

- Follow the ABCDE rule to tell the difference between a normal mole and melanoma.

- Biopsy is used to diagnose skin cancer.

- Skin cancer can be treated with surgery, medicine, and radiation.

- Staying out of the sun is the best way to prevent skin cancer.

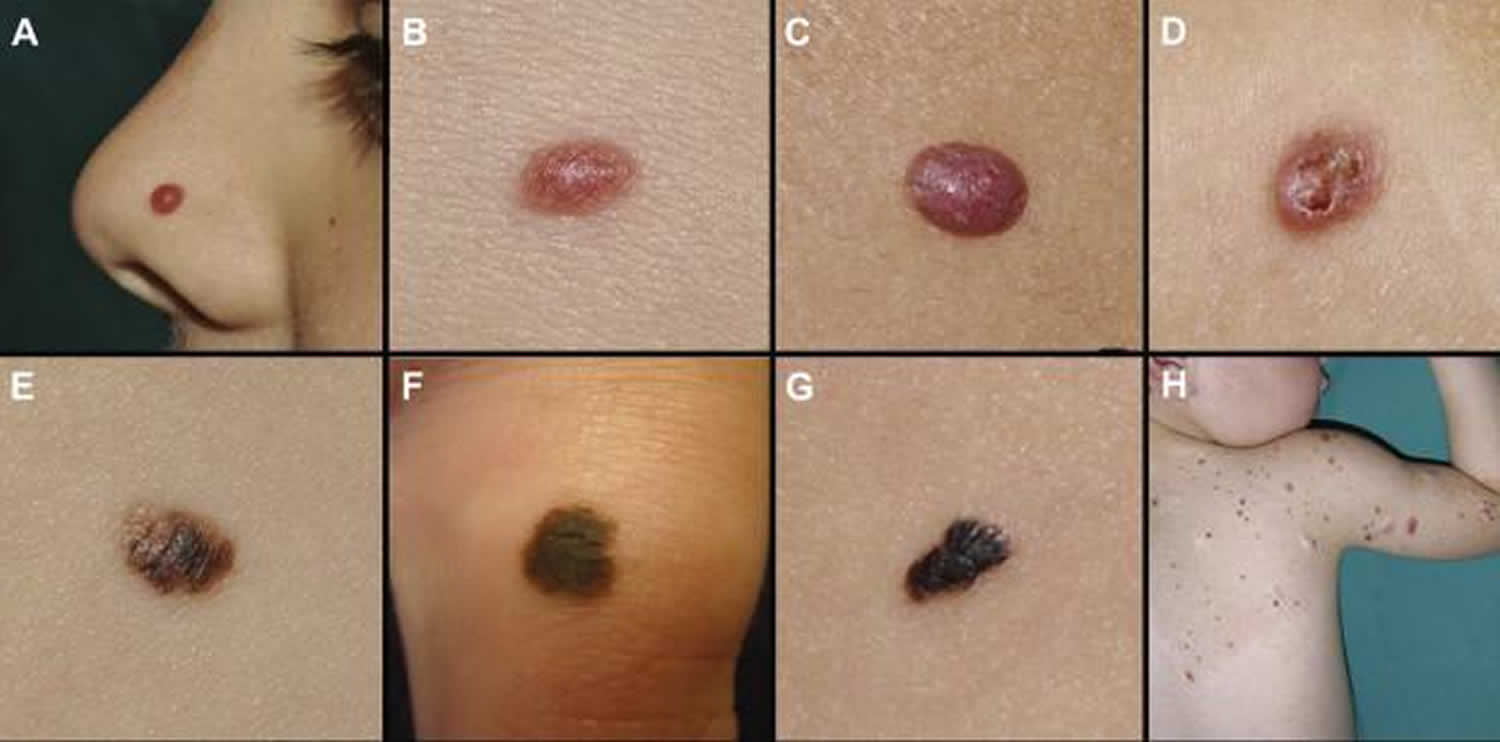

Figure 1. Melanoma in children

Figure 2. Squamous cell carcinoma in children

Figure 3. Basal cell carcinoma in children

Figure 4. Skin anatomy

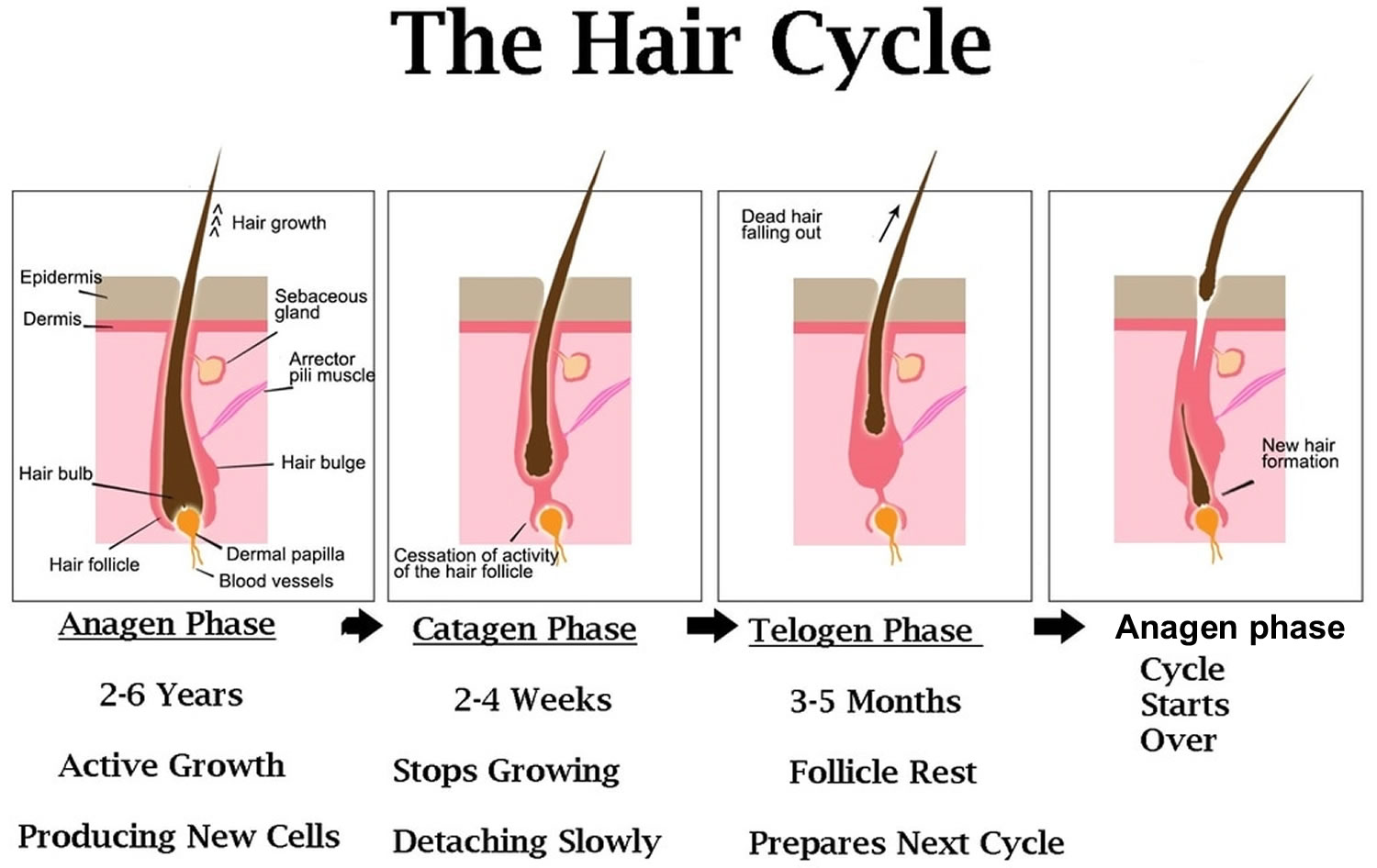

Basal cell carcinoma in children

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is a common, locally invasive, keratinocyte cancer also known as non-melanoma cancer. Basal cell carcinoma is very rarely a threat to life. Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common form of skin cancer. Basal cell carcinoma is also known as rodent ulcer and basalioma. Patients with basal cell carcinoma often develop multiple primary tumors over time.

Basal cell carcinoma main characteristics are:

- Slowly growing plaque or nodule

- Skin coloured, pink or pigmented

- Varies in size from a few millimetres to several centimetres in diameter

- Spontaneous bleeding or ulceration

A tiny proportion of basal cell carcinomas grow rapidly, invade deeply, and/or metastasise to local lymph nodes.

The cause of basal cell carcinoma is multifactorial:

- Most often, there are DNA mutations in the patched (PTCH) tumour suppressor gene, part of hedgehog signalling pathway

- These may be triggered by exposure to ultraviolet radiation

- Various spontaneous and inherited gene defects predispose to basal cell carcinoma

Risk factors for basal cell carcinoma include:

- Age and sex: basal cell carcinomas are particularly prevalent in elderly males. However, they also affect females and younger adults

- Previous basal cell carcinoma or other form of skin cancer (squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma)

- Sun damage (photoaging, actinic keratosis)

- Repeated prior episodes of sunburn

- Fair skin, blue eyes and blond or red hair—note; basal cell carcinoma can also affect darker skin types

- Previous cutaneous injury, thermal burn, disease (eg cutaneous lupus, sebaceous nevus)

- Inherited syndromes: basal cell carcinoma is a particular problem for families with basal cell naevus syndrome (Gorlin syndrome), Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome, Rombo syndrome, Oley syndrome and xeroderma pigmentosum

- Other risk factors include ionizing radiation, exposure to arsenic, and immune suppression due to disease or medicines

Types of basal cell carcinoma

There are several distinct clinical types of basal cell carcinoma, and over 20 histological growth patterns of basal cell carcinoma.

Nodular basal cell carcinoma

- Also known as nodulocystic carcinoma

- Most common type of facial basal cell carcinoma

- Shiny or pearly nodule with a smooth surface

- May have central depression or ulceration, so its edges appear rolled

- Blood vessels cross its surface

- Cystic variant is soft, with jelly-like contents

- Micronodular, microcystic and infiltrative types are potentially aggressive subtypes

Superficial basal cell carcinoma

- Most common type in younger adults

- Most common type on upper trunk and shoulders

- Slightly scaly, irregular plaque

- Thin, translucent rolled border

- Multiple microerosions

Morphoeic basal cell carcinoma

- Also known as morpheic, morphoeiform or sclerosing basal cell carcinoma

- Usually found in mid-facial sites

- Waxy, scar-like plaque with indistinct borders

- Wide and deep subclinical extension

- May infiltrate cutaneous nerves (perineural spread)

Basosquamous carcinoma

- Also known as basisquamous carcinoma and mixed basal-squamous cell carcinoma

- Mixed basal cell carcinoma (basal cell carcinoma) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

- Infiltrative growth pattern

- Potentially more aggressive than other forms of basal cell carcinoma

Primary basal cell carcinoma treatment

The treatment for a basal cell carcinoma depends on its type, size and location, the number to be treated, patient factors, and the preference or expertise of the doctor. Most basal cell carcinomas are treated surgically. Long-term follow-up is recommended to check for new lesions and recurrence; the latter may be unnecessary if histology has reported wide clear margins.

Excision biopsy

Excision means the lesion is cut out and the skin stitched up.

- Most appropriate treatment for nodular, infiltrative and morphoeic basal cell carcinomas

- Should include 3 to 5 mm margin of normal skin around the tumor

- Very large lesions may require flap or skin graft to repair the defect

- Pathologist will report deep and lateral margins

- Further surgery is recommended for lesions that are incompletely excised

Mohs micrographically controlled excision

Mohs micrographically controlled surgery involves examining carefully marked excised tissue under the microscope, layer by layer, to ensure complete excision.

- Very high cure rates achieved by trained Mohs surgeons

- Used in high-risk areas of the face around eyes, lips and nose

- Suitable for ill-defined, morphoeic, infiltrative and recurrent subtypes

- Large defects are repaired by flap or skin graft

Superficial skin surgery

Superficial skin surgery comprises shave, curettage, and electrocautery. It is a rapid technique using local anaesthesia and does not require sutures.

- Suitable for small, well-defined nodular or superficial basal cell carcinomas

- Lesions are usually located on trunk or limbs

- Wound is left open to heal by secondary intention

- Moist wound dressings lead to healing within a few weeks

- Eventual scar quality variable

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy is the treatment of a superficial skin lesion by freezing it, usually with liquid nitrogen.

- Suitable for small superficial basal cell carcinomas on covered areas of trunk and limbs

- Best avoided for basal cell carcinomas on head and neck, and distal to knees

- Double freeze-thaw technique

- Results in a blister that crusts over and heals within several weeks.

- Leaves permanent white mark

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) refers to a technique in which basal cell carcinoma is treated with a photosensitising chemical, and exposed to light several hours later.

- Topical photosensitisers include aminolevulinic acid lotion and methyl aminolevulinate cream

- Suitable for low-risk small, superficial basal cell carcinomas

- Best avoided if tumor in site at high risk of recurrence

- Results in inflammatory reaction, maximal 3–4 days after procedure

- Treatment repeated 7 days after initial treatment

- Excellent cosmetic results

Imiquimod cream

Imiquimod is an immune response modifier.

- Best used for superficial basal cell carcinomas less than 2 cm diameter

- Applied three to five times each week, for 6–16 weeks

- Results in a variable inflammatory reaction, maximal at three weeks

- Minimal scarring is usual

Fluorouracil cream

5-Fluorouracil cream is a topical cytotoxic agent.

- Used to treat small superficial basal cell carcinomas

- Requires prolonged course, eg twice daily for 6–12 weeks

- Causes inflammatory reaction

- Has high recurrence rates

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy or X-ray treatment can be used to treat primary basal cell carcinomas or as adjunctive treatment if margins are incomplete.

- Mainly used if surgery is not suitable

- Best avoided in young patients and in genetic conditions predisposing to skin cancer

- Best cosmetic results achieved using multiple fractions

- Typically, patient attends once-weekly for several weeks

- Causes inflammatory reaction followed by scar

- Risk of radiodermatitis, late recurrence, and new tumors

Advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma treatment

Locally advanced primary, recurrent or metastatic basal cell carcinoma requires multidisciplinary consultation. Often a combination of treatments is used.

- Surgery

- Radiotherapy

- Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy refers to the hedgehog signalling pathway inhibitors, vismodegib and sonidegib. These drugs have some important risks and side effects.

Basal cell carcinoma prognosis

Most basal cell carcinomas are cured by treatment. Cure is most likely if treatment is undertaken when the lesion is small.

Death from basal and squamous cell skin cancers is uncommon. It’s thought that about 2,000 people in the US die each year from these cancers, and that this rate has been dropping in recent years. Most people who die from these cancers are elderly and may not have seen a doctor until the cancer had already grown quite large. Other people more likely to die of these cancers are those whose immune system is suppressed, such as people who have had organ transplants.

About 50% of people with basal cell carcinoma develop a second one within 3 years of the first. They are also at increased risk of other skin cancers, especially melanoma. Regular self-skin examinations and long-term annual skin checks by an experienced health professional are recommended.

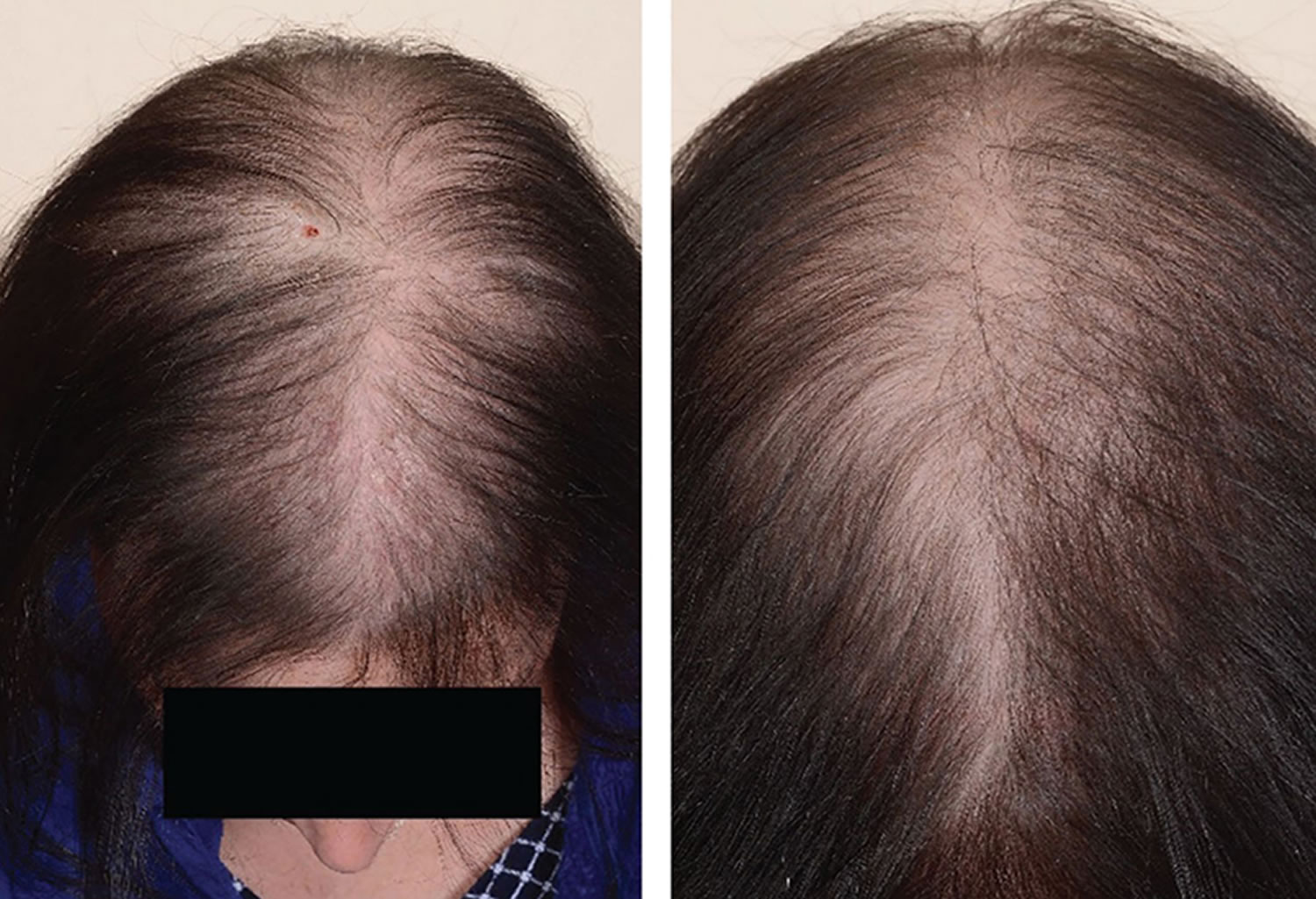

Squamous cell carcinoma in children

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a common type of keratinocyte cancer, or non-melanoma skin cancer. It is derived from cells within the epidermis that make keratin — the horny protein that makes up skin, hair and nails.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is an invasive disease, referring to cancer cells that have grown beyond the epidermis. Squamous cell carcinoma can sometimes metastasise (spread) and may prove fatal.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas present as enlarging scaly or crusted lumps. They usually arise within pre-existing actinic keratosis or intraepidermal carcinoma.

- They grow over weeks to months

- They may ulcerate

- They are often tender or painful

- Located on sun-exposed sites, particularly the face, lips, ears, hands, forearms and lower legs

- Size varies from a few millimetres to several centimetres in diameter.

Types of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

Distinct clinical types of invasive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma include:

- Cutaneous horn — the horn is due to excessive production of keratin

- Keratoacanthoma — a rapidly growing keratinising nodule that may resolve without treatment

- Carcinoma cuniculatum (‘verrucous carcinoma’), a slow-growing, warty tumour on the sole of the foot.

- Multiple eruptive squamous cell carcinoma/keratoacanthoma-like lesions arising in syndromes, such as multiple self-healing squamous epitheliomas of Ferguson-Smith and Grzybowski syndrome

The histopathologist may classify a tumor as well differentiated, moderately well differentiated, poorly differentiated or anaplastic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. There are other variants.

Causes cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

More than 90% of cases of squamous cell carcinoma are associated with numerous DNA mutations in multiple somatic genes. Mutations in the p53 tumour suppressor gene are caused by exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UV), especially UVB (known as signature 7). Other signature mutations relate to cigarette smoking, ageing and immune suppression (eg, to drugs such as azathioprine). Mutations in signalling pathways affect the epidermal growth factor receptor, RAS, Fyn, and p16INK4a signalling.

Beta-genus human papillomaviruses (wart virus) are thought to play a role in squamous cell carcinoma arising in immune-suppressed populations. β-HPV and HPV subtypes 5, 8, 17, 20, 24, and 38 have also been associated with an increased risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in immunocompetent individuals.

Risk factors for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma include:

- Age and sex: squamous cell carcinomas are particularly prevalent in elderly males. However, they also affect females and younger adults.

- Previous squamous cell carcinoma or another form of skin cancer (basal cell carcinoma, melanoma) are a strong predictor for further skin cancers.

- Actinic keratosis

- Outdoor occupation or recreation

- Smoking

- Fair skin, blue eyes and blond or red hair

- Previous cutaneous injury, thermal burn, disease (eg cutaneous lupus, epidermolysis bullosa, leg ulcer)

- Inherited syndromes: squamous cell carcinoma is a particular problem for families with xeroderma pigmentosum and albinism

- Other risk factors include ionising radiation, exposure to arsenic, and immune suppression due to disease (eg chronic lymphocytic leukaemia) or medicines. Organ transplant recipients have a massively increased risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma treatment

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is nearly always treated surgically. Most cases are excised with a 3–10 mm margin of normal tissue around a visible tumor. A flap or skin graft may be needed to repair the defect.

Other methods of removal include:

- Shave, curettage, and electrocautery for low-risk tumours on trunk and limbs

- Aggressive cryotherapy for very small, thin, low-risk tumors

- Mohs micrographic surgery for large facial lesions with indistinct margins or recurrent tumours

- Radiotherapy for an inoperable tumour, patients unsuitable for surgery, or as adjuvant

Advanced or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma treatment

Locally advanced primary, recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma requires multidisciplinary consultation. Often a combination of treatments is used.

- Surgery

- Radiotherapy

- Cemiplimab

- Experimental targeted therapy using epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors

The exact number of people who develop or die from basal and squamous cell skin cancers each year isn’t known for sure. Death from basal and squamous cell skin cancers is uncommon. It’s thought that about 2,000 people in the US die each year from these cancers, and that this rate has been dropping in recent years. Most people who die from these cancers are elderly and may not have seen a doctor until the cancer had already grown quite large. Other people more likely to die of these cancers are those whose immune system is suppressed, such as people who have had organ transplants.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma prognosis

Most squamous cell carcinomas are cured by treatment. A cure is most likely if treatment is undertaken when the lesion is small. The risk of recurrence or disease-associated death is greater for tumours that are > 20 mm in diameter and/or > 2 mm in thickness at the time of surgical excision.

About 50% of people at high risk of squamous cell carcinoma develop a second one within 5 years of the first. They are also at increased risk of other skin cancers, especially melanoma. Regular self-skin examinations and long-term annual skin checks by an experienced health professional are recommended.

Melanoma in children

Melanoma is a skin cancer that arises from melanocytes (pigment-producing cells). Childhood melanoma usually refers to melanoma diagnosed in individuals under the age of 18 years.

Cutaneous melanoma in children is rare, and extremely rare before puberty 1. Melanoma comprises 3% of all pediatric cancers 2.

Melanoma arising in children has been classified into the following types 3:

- Melanoma present at birth (congenital melanoma)

- Melanoma developing in congenital melanocytic nevus (brown birthmark)

- Melanoma arising in patients with dysplastic or atypical nevi (most often superficial spreading melanoma arising de novo)

- Malignant blue nevus

- Nodular melanoma (40-50% of malignant melanoma in children)

- Spitzoid melanoma

Risk factors for childhood melanoma include 4:

- Giant congenital nevus

- Fitzpatrick skin phototypes I-II (i.e. fair skin that burns easily and tans poorly, freckles)

- Immunodeficiency or immunosuppression

- History of retinoblastoma

- Familial atypical naevi (dysplastic naevus syndrome)

- Many moles

- Xeroderma pigmentosum (a very rare disorder with extreme sensitivity to sunlight)

Like the adult population, melanoma mainly affects Caucasian children and is associated with sun exposure. There is a slight female preponderance 1.

Melanoma in a congenital melanocytic nevus

Small congenital nevi arise in 1 in 100 births. Melanoma is a rare complication of small to medium congenital nevi. It tends to appear on the edge of the birthmark and is recognized by change within the mole and the ABCDE criteria.

The risk of melanoma is higher in larger congenital nevi 5. Melanoma arises in about 4% of children 10 years or younger that have a giant congenital melanocytic nevus >40 cm in diameter. Giant congenital melanocytic nevi are very rare, arising in 1 in 20,000 births. In giant congenital melanocytic nevi:

- Melanoma may arise within the centre of the melanoma

- It tends to arise within deeper dermal naevus cells rather than within superficial naevus cells

- The melanoma may also arise within the central nervous system due to neurocutaneous melanocytosis

- The risk of melanoma is greater in giant naevi that cross the midline of the spine and in children with satellite naevi

- Prophylactic removal of the naevi does not appear to reduce the risk of melanoma

These melanomas can be difficult to detect early. Excision may also be difficult or impossible.

Melanoma in children aged 11 and older

Melanoma in older children appears similar to melanoma in adults; it presents as a growing lesion that looks different from the child’s other lesions. Most are pigmented. About 60% have the ABCDE criteria.

- A: Asymmetry

- B: Border irregularity

- C: Color variation

- D: Diameter >6 mm

- E: Evolving

Melanoma in children aged 10 or younger

Superficial spreading melanoma is less common in younger children and melanoma has the ABCDE criteria in 40% of cases.

Melanoma in young children is more commonly amelanotic (red coloured), nodular, and tends to be thicker at diagnosis than in older children and adults.

Cordoro et al 6 have suggested adding additional ABCD detection criteria for skin lesions in children:

- A: Amelanotic (the lesion is skin colored or red)

- B: Bleeding, Bump

- C: Color uniformity

- D: De novo, any Diameter

Childhood melanoma treatment

Treatment of childhood melanoma is the same as in adults.

- Lesions that are suspicious for melanoma are completely removed by initial diagnostic excision biopsy, usually with a 2-mm clinical margin.

- If melanoma is confirmed, a second surgical procedure is undertaken to remove a wider margin of normal skin. This is called wide local excision. The size of the margin depends on the Breslow thickness of the melanoma.

- If the melanoma has thickness >1 mm or other features of concern, sentinel node biopsy may be offered. However, its role in the pediatric population is not well established.

- Follow-up is arranged to look for recurrence and new lesions of concern 7.

Metastatic melanoma or advanced melanoma is melanoma that has spread to lymph nodes or elsewhere in the body. Treatment is individualized but may include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy or targeted therapy.

Childhood melanoma prognosis

Prognosis of melanoma depends on the stage of melanoma, ie whether it has spread beyond its original site in the skin. Spread of melanoma to lymph nodes and elsewhere is more likely in thicker tumors (measured by Breslow thickness at the time of removal of a primary tumor).

Survival rates are similar in older children and adults 2. However, melanomas in children under 11 years of age appear to have a less aggressive behavior than those detected in adults 1.

What causes skin cancer in kids?

The common forms of skin cancer listed above are related to exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sunlight or tanning beds or lamps and the effects of ageing. Skin cancer is more common in people with light skin, light-colored eyes, and blond or red hair.

Other risk factors include:

- Smoking (especially for squamous cell carcinoma)

- Human papillomavirus infection (genital warts), particularly for mucosal sites such as oral mucosa, lips and genitals

- Immune suppression, for example in patients who have received an organ transplant and are on azathioprine and ciclosporin

- Human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV)

- Exposure to ionizing radiation or radiation therapy in the past

- Exposure to certain chemicals, such as arsenic and coal tar

- Longstanding skin diseases such as lichen sclerosus, lupus erythematosus, linear porokeratosis or cutaneous tuberculosis

- A longstanding wound or scar, for example, from a thermal burn (a Marjolin ulcer).

- Age.

- Time spent in the sun

- History of sunburns

- Actinic keratoses or Bowen disease. These are rough or scaly red or brown patches on the skin.

- Family history of skin cancer

- Having many freckles

- Having many moles

- Having skin cancer in the past

- Having atypical moles (dysplastic nevi). These large, oddly shaped moles run in families.

- Taking a medicine that suppresses the immune system.

Some skin cancers are due to genetic conditions, such as:

- Albinism

- Basal cell nevus syndrome (Gorlin syndrome)

- Bazex–Dupré–Christol syndrome

- Bloom syndrome

- Brooke-Spiegler syndrome

- Cowden syndrome

- Dyskeratosis congenita

- Epidermolysis bullosa

- Epidermodysplasia verruciformis

- Familial atypical mole-melanoma syndrome (FAMM)

- Premature ageing syndromes (progeria)

- Rothmund-Thomson syndrome

- Torré-Muir syndrome

- Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP).

Skin cancer in children prevention

The American Academy of Dermatology and the Skin Cancer Foundation advise you to:

- Limit how much sun your child gets between the hours of 10 a.m. and 4 p.m.

- Use broad-spectrum sunscreen with an SPF 30 or higher that protects against both UVA and UVB rays. Put it on the skin of children older than 6 months of age who are exposed to the sun.

- Reapply sunscreen every 2 hours, even on cloudy days. Reapply after swimming.

- Use extra caution near water, snow, and sand. They reflect the damaging rays of the sun. This can increase the chance of sunburn.

- Make sure your child wears clothing that covers the body and shades the face. Hats should provide shade for both the face, ears, and back of the neck. Wearing sunglasses will reduce the amount of rays reaching the eye and protect the lids of the eyes, as well as the lens.

- Don’t let your child use or be around sunlamps or tanning beds.

The American Academy of Pediatrics approves of the use of sunscreen on babies younger than 6 months old if adequate clothing and shade are not available. You should still try to keep your baby out of the sun. Dress the baby in lightweight clothing that covers most surface areas of skin. But you also may use a small amount of sunscreen on the baby’s face and back of the hands.

Skin cancer in children symptoms

Skin cancers generally appear as a lump or nodule, an ulcer, or a changing lesion.

Symptoms of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) appear on areas exposed to the sun, such as the head, face, neck, arms, and hands. The symptoms can include:

- A small, raised bump that is shiny or pearly, and may have small blood vessels

- A small, flat spot that is scaly, irregularly shaped, and pale, pink, or red

- A spot that bleeds easily, then heals and appears to go away, then bleeds again in a few weeks

- A growth with raised edges, a lower area in the center, and brown, blue, or black areas

Symptoms of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) appear on areas exposed to the sun, such as the head, face, neck, arms, and hands. They can also appear on other parts of the body, such as skin in the genital area. The symptoms can include:

- A rough or scaly bump that grows quickly

- A wart-like growth that may bleed or crust over.

- Flat, red patches on the skin that are irregularly shaped, and may or may not bleed

Symptoms of melanoma include a change in a mole, or a new mole that has ABCDE traits such as:

- Asymmetry. One half of the mole does not match the other half.

- Border irregularity. The edges of the mole are ragged or irregular.

- Color. The mole has different colors in it. It may be tan, brown, black, red, or other colors. Or it may have areas that appear to have lost color.

- Diameter. The mole is bigger than 6 millimeters across, about the size of a pencil eraser. But some melanomas can be smaller.

- Evolving. A mole changes in size, shape, or color.

Other symptoms of melanoma can include a mole that:

- Itches or hurts

- Oozes, bleeds, or becomes crusty

- Turns red or swells

- Looks different from your child’s other moles.

Complications of skin cancer in children

Skin cancer can usually be treated and cured before complications occur. Signs of advanced, aggressive or neglected skin cancer may include:

- Ulceration

- Bleeding

- Spread of a tumor to lymph glands and other organs such as liver and brain (metastasis).

Possible complications depend on the type and stage of skin cancer. Melanoma is more likely to cause complications. And the more advanced the cancer, the more likely there will be complications.

Complications may result from treatment, such as:

- Loss of large areas of skin and underlying tissue

- Scarring

- Problems with the area healing

- Infection in the area

- Damage to nerves

- Return of the skin cancer after treatment

Melanoma may spread to organs throughout the body and cause death.

Skin cancer in children diagnosis

Skin cancers are generally diagnosed clinically by a dermatologist or family doctor, when learning of an enlarging, crusting or bleeding lesion. The lesion will be inspected carefully, and ideally, a full skin examination will also be conducted. Dermatoscopy (a special magnifying light) may be used to confirm the diagnosis, to detect early skin cancers, and to exclude benign lesions.

Your doctor will examine your child’s skin. Tell your doctor:

- When you first noticed the skin problem

- If it oozes fluid or bleeds, or gets crusty

- If it’s changed in size, color, or shape

- If your child has pain or itching

Tell your doctor if your child has had skin cancer in the past, and if other your family members have had skin cancer.

Your child’s doctor will likely take a small piece of tissue (biopsy) from a mole or other skin mark that may look like cancer to confirm the diagnosis. The tissue is sent to a lab. A doctor called a histopathologist looks at the tissue under a microscope. He or she may do other tests to see if cancer cells are in the sample. It can take a few days for the report to be issued, or longer if special tests are required. The biopsy results will likely be ready in a few days or a week. Your child’s doctor will tell you the results. He or she will talk with you about other tests that may be needed if cancer is found.

Complete excision is usually undertaken to make a diagnosis if melanoma is suspected, as a partial biopsy can be misleading in melanocytic tumors. Genetic testing for melanoma and blood-based melanoma detection may be available in some centers.

Skin cancer in children treatment

Early treatment of skin cancer usually cures it. The majority of skin cancers are treated surgically, using a local anesthetic to numb the skin. Surgical techniques include:

- Excision biopsy

- Simple excision: This is done to cut the cancer from the skin, along with some of the healthy tissue around it. Your child is given a local anesthetic. Then, the doctor uses a scalpel to remove the tumor from the skin. The doctor may also remove some of the normal skin around the tumor. This is called a margin. Stitches or a bandage strip may be used to close the wound. The tissue that was removed is sent to a lab for testing. If the report shows that not all the cancer was removed, your child will likely need another procedure to remove the rest of the cancer.

- Shave excision: This method is used for cancer that is only in the top layers of the skin. Your child is given a local anesthetic. Then, the doctor uses a small blade to shave off the tumor. The goal is to remove the tumor at its base.

- Mohs surgery: This procedure removes the cancer and a small amount of normal tissue. It’s done on sensitive areas, such as the face. During Mohs surgery, your child is given a local anesthetic to numb the area being treated. The cancer is removed from the skin one layer at a time. Each layer is checked under a microscope for cancer. If cancer cells are seen, another layer of skin is removed. Layers are removed until the doctor doesn’t see any more cancer. The procedure may take several hours, depending on how many layers need to be removed. After this surgery, the cancer is fully removed and the wound can be repaired.

Treatment options for superficial skin cancers include:

- Minor surgery including curettage and diathermy/cautery and electrosurgery: This procedure removes tissue and burns (cauterizes) the area. Your child is given a local anesthetic to numb the area. The doctor then uses a sharp spoon-shaped tool called a curette to remove the cancer. This is called curettage. After curettage, the doctor passes an electric needle over the surface of the scraped area to stop bleeding, and destroy any other cancer cells. After it heals, a flat white scar may remain.

- Cryotherapy: This method uses cold to destroy the cancer cells. This method is best for very small cancers near the skin’s surface. The doctor uses a device that sprays liquid nitrogen onto the tumor. This freezes the cells and destroys them. The dead skin then falls off. Your child may have some swelling and blistering in the area after treatment. A white scar is usually left behind. The procedure may need to be repeated.

- Topical chemotherapy such as fluorouracil cream, imiquimod cream or ingenol mebutate gel. This kind of medicine is only used if the cancer is just in the top layers of the skin. The medicine is applied several times a week for a few weeks.

- Photodynamic therapy (photosensitising cream plus light)

- Radiotherapy (x-ray treatment): This is treatment with high-energy X-rays. Electron beam radiation is often used for skin cancer. This type of radiation doesn’t go deeper than the skin. This helps limit side effects. The radiation damages the cancer cells and stops them from growing. Radiation therapy is a local therapy. This means that it affects the cancer cells only in the treated area.

- Lasers

Treatment for advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma may include targeted therapies vismodegib and sonidegib.

Treatment for advanced and metastatic melanoma may include:

- Systemic immunotherapy using ipilimumab or checkpoint inhibitors pembrolizumab or nivolumab

- Topical and intralesional immunotherapy for melanoma metastases

- Targeted therapy against BRAF mutations using vemurafenib or dabrafenib or MEK inhibition with trametinib. The goal of targeted therapy is to shrink advanced melanoma tumors. This type of therapy is done with medicines that target specific parts of melanoma cells. For example, medicines called BRAF inhibitors target cells with a change in the BRAF gene. This gene is found in about half of all melanomas.

- Combination medications, such as cometinib.

Patients with skin cancer may be at increased risk of developing other skin cancers. They may be advised to:

- Practice careful sun protection, including the regular application of sunscreens

- Learn and practice self-skin examination

- Have regular skin checks

- Undergo digital dermatoscopic surveillance (mole mapping), especially if they have many moles or atypical moles

- Seek medical attention if they notice any changing or enlarging skin lesions

- Take nicotinamide (vitamin B3) to reduce the numbers of squamous cell carcinomas.

Living with skin cancer in kids

If your child has skin cancer, you can help him or her during treatment in these ways:

- Your child may have trouble eating. A dietitian or nutritionist may be able to help.

- Your child may be very tired. He or she will need to learn to balance rest and activity.

- Get emotional support for your child. Counselors and support groups can help.

- Keep all follow-up appointments.

- Keep your child out of the sun.

After treatment, check your child’s skin every month or as often as advised.

- Paradela S, Fonseca E, Pita-Fernández S, et al. Prognostic factors for melanoma in children and adolescents: a clinicopathologic, single-center study of 137 Patients. Cancer. 2010;116(18):4334-4344. doi:10.1002/cncr.25222[↩][↩][↩]

- Han D, Zager JS, Han G, et al. The unique clinical characteristics of melanoma diagnosed in children. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(12):3888-3895. doi:10.1245/s10434-012-2554-5[↩][↩]

- Mehregan AH, Mehregan DA. Malignant melanoma in childhood. Cancer. 1993;71(12):4096-4103. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19930615)71:12<4096::aid-cncr2820711248>3.0.co;2-z[↩]

- Paradela S, Fonseca E, Prieto VG. Melanoma in children. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135(3):307-316. doi:10.1043/2009-0503-RA.1[↩]

- Vourc’h-Jourdain M, Martin L, Barbarot S; aRED. Large congenital melanocytic nevi: therapeutic management and melanoma risk: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(3):493-8.e14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.09.039[↩]

- Cordoro KM, Gupta D, Frieden IJ, McCalmont T, Kashani-Sabet M. Pediatric melanoma: results of a large cohort study and proposal for modified ABCD detection criteria for children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(6):913-925. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.12.953[↩]

- Rao BN, Hayes FA, Pratt CB, et al. Malignant melanoma in children: its management and prognosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25(2):198-203. doi:10.1016/0022-3468(90)90402-u[↩]