What is CD4 count

CD4 count is a laboratory test that measures CD-4 T lymphocytes (T cells) via flow cytometry. CD4 T cells help to fight infection and play an important role in your immune system function. CD4 count test is an important parameter in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) management and is used to guide clinical treatment. The CD4 count is a reliable indicator of a patient’s immunologic status and is used to determine the necessity for initiation of prophylactic treatment against opportunistic infections 1. The CD4 molecule is a member of the immunoglobulin family and primarily mediates adhesion to major histocompatibility complex molecules. CD4 T cells are selectively targeted and infected by HIV. HIV proliferates rapidly during acute infection leading to high levels of viremia and rapid impairment and death of CD4 T cells.

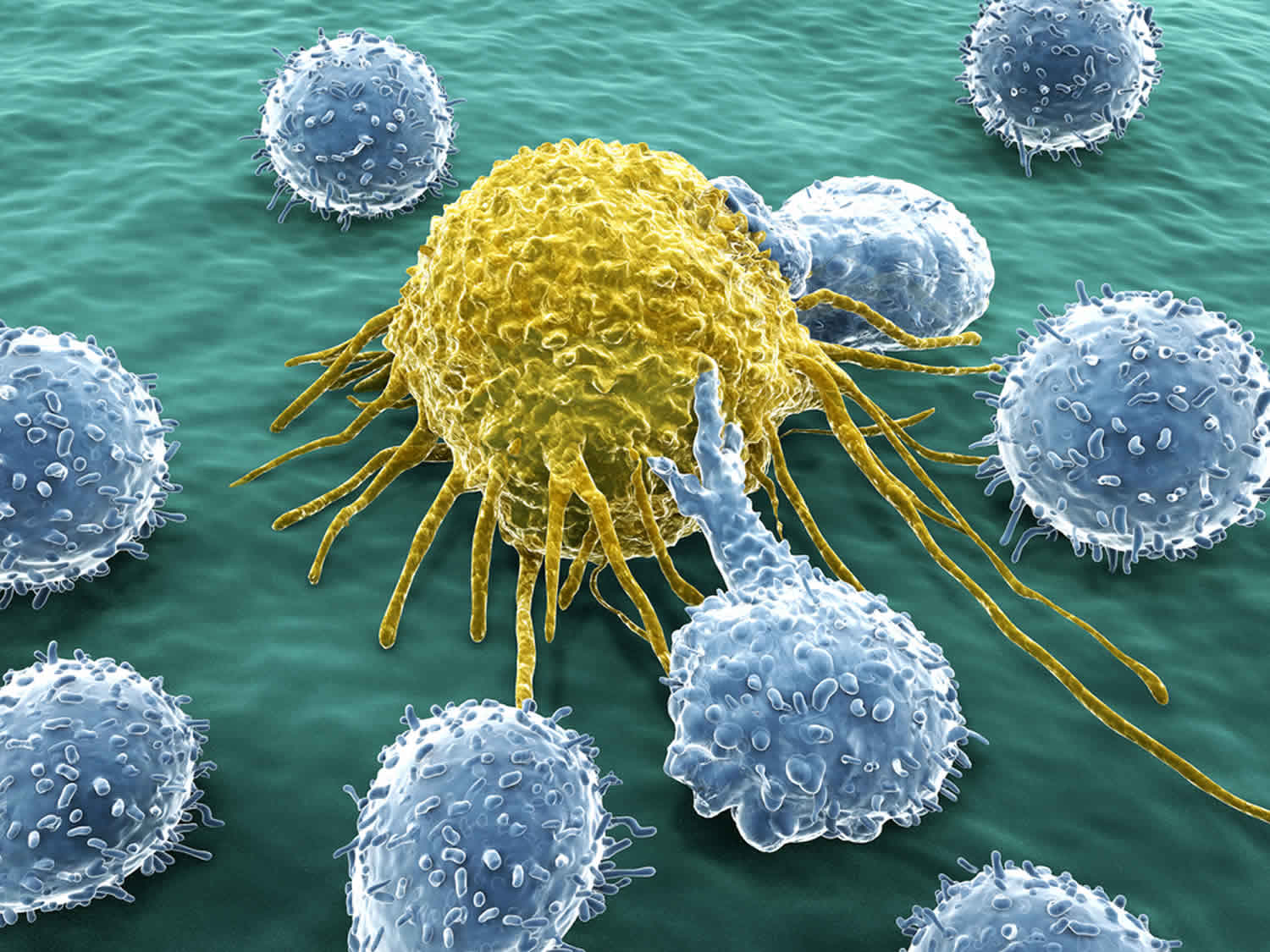

CD4 T cells are white blood cells called helper T lymphocytes or helper T cells that express cluster determinant 4 (CD4) molecules or markers on their surfaces. The CD number identifies the specific type of cell. CD4 cells are sometimes called T-helper cells. CD4 T cells help to identify, attack, and destroy specific bacteria, fungi, and viruses that cause infections. CD4 cells are a major target for HIV, which binds to the surface of CD4 cells, enters them, and either replicates immediately, killing the cells in the process, or remains in a resting state, replicating later.

If HIV goes untreated, the virus gets into the cells and replicates, the viral load increases, and the number of CD4 cells in the blood gradually declines. The CD4 count decreases as the disease progresses. If still untreated, this process may continue for several years until the number of CD4 cells drops to a low enough level that symptoms associated with AIDS begin to appear.

Treatment for HIV infection, called antiretroviral treatment (ART or ARV) or sometimes highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), typically involves taking a combination of drugs. This treatment reduces the amount of HIV (viral load) present in your body and reduces the risk of disease progression. When this occurs, the CD4 count will increase and/or stabilize.

CD8 cells are another type of lymphocyte. They are sometimes called T-suppressor cells or cytotoxic T cells. CD8 cells (cytotoxic T cells) identify and kill cells that have been infected with viruses or that have been affected by cancer. CD8 cells (cytotoxic T cells) play an important role in the immune response to HIV infection by killing cells infected with the virus and by producing substances that block HIV replication.

As HIV disease progresses, the number of CD4 cells will decrease in relation to the number of total lymphocytes and CD8 cells. To provide a clearer picture of the condition of your immune system, test results may be reported as a ratio of CD4 to total lymphocytes (percentage).

CD4 and CD8 tests may be used occasionally in other conditions, such as lymphomas and organ transplantation.

CD4 T cells are made in the thymus gland and they circulate throughout your body in the blood and lymphatic system. CD4 count tests measure the number of these cells in your blood and, in conjunction with an HIV viral load test, help assess the status of the immune system in a person who has been diagnosed with HIV infection.

Viral load (HIV RNA). This test measures the amount of virus in your blood. A higher viral load has been linked to a worse outcome.

How is the sample collected for testing?

A health care professional will take a blood sample from a vein in your arm, using a small needle. After the needle is inserted, a small amount of blood will be collected into a test tube or vial. You may feel a little sting when the needle goes in or out. This usually takes less than five minutes.

Is any test preparation needed to ensure the quality of the sample?

No test preparation is needed.

How is HIV infection diagnosed?

HIV infection is usually screened for with an HIV antibody test or a combination test for HIV antibody and antigen (p24). If the screening test is positive, it must be followed with another test, such as a second antibody test that can differentiate HIV-1 and HIV-2. If results of the first and second test do not agree, then the next test to perform is an HIV-1 RNA test (nucleic acid amplification test, NAAT). If either the second antibody test or the HIV-1 RNA is positive, then the person tested is diagnosed with HIV infection.

Why do I need a CD4 count?

Your health care provider may order a CD4 count when you are first diagnosed with HIV. You will probably be tested again every few months to see if your counts have changed since your first test. If you are being treated for HIV, your health care provider may order regular CD4 counts to see how well your medicines are working.

CD4 count monitoring is primarily used to assess when to initiate prophylaxis against several opportunistic infections. Although it is also obtained in monitoring response to ART (antiretroviral therapy), CD4 count is, by itself, insufficient in evaluating response to therapy. Viral load monitoring remains the most reliable indicator of treatment response. The CD4 count must be obtained at baseline 3 months after initiation of ART (antiretroviral therapy). It is subsequently monitored every 3 to 6 months during therapy. According to treatment guidelines, less frequent monitoring (every 12 months) may be done after 2 years of ART in patients who have a stable CD4 count of greater than 300 cells/mm³ and consistently undetectable viral load.

Your doctor may include other tests with your CD4 count, including:

- A CD4-CD8 ratio. CD8 cells are another type of white blood cell in the immune system. CD8 cells kill cancer cells and other invaders. This test compares the numbers of the two cells to get a better idea of immune system function.

- HIV viral load, a test that measures the amount of HIV in your blood.

What is CD4 count used for?

A CD4 count is usually ordered along with an HIV viral load when a person is first diagnosed with HIV infection as part of a baseline measurement. After the baseline, a CD4 count will usually be ordered at intervals over time, depending on a few different factors.

A CD4 count may be used to:

- See how HIV is affecting your immune system. This can help your health care provider find out if you are at higher risk for complications from the disease.

- Decide whether to start or change your HIV medicine

- Diagnose AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome)

- The names HIV and AIDS are both used to describe the same disease. But most people with HIV don’t have AIDS. AIDS is diagnosed when your CD4 count is extremely low.

- AIDS is the most severe form of HIV infection. It badly damages the immune system and can lead to opportunistic infections. These are serious, often life-threatening, conditions that take advantage of very weak immune systems.

You may also need a CD4 count if you’ve had an organ transplant. Organ transplant patients take special medicines to make sure the immune system won’t attack the new organ. For these patients, a low CD4 count is good, and means the medicine is working.

Table 1. Recommendations for the timing of CD4 counts and viral load testing

| Clinical Status of Patient | Viral Load | CD4 Count |

| When first diagnosed | Test performed | Test performed |

| After initiating ART | Within 2-4 weeks and then every 4-8 weeks until virus is suppressed (undetectable) | 3 months later |

| During the first 2 years of stable ART | Every 3-4 months | Every 3-6 months |

| After 2 years of stable ART, virus undetectable, and CD4 greater than 300 cells/mm3 | Can extend to every 6 months | Annually; if CD4 consistently greater than 500 cells/mm3, monitoring is optional |

| After changing ART due to side effects or simplifying drug regimen in a person with suppressed virus | After 4-8 weeks, to confirm drug effectiveness | Monitor according to prior CD4 count and the amount of time person has been on ART, as detailed above |

| After changing ART due to increased viral load (treatment failure) | Within 2-4 weeks and then every 4-8 weeks until virus undetectable | Every 3-6 months |

| While on ART and viral load is consistently greater than 200 copies/mL | Every 3 months | Every 3-6 months |

| With new HIV symptoms or start of new treatment with interferon, corticosteroids or cancer drugs | Every 3 months | Perform test and monitor according to health status (e.g., new HIV symptoms, opportunistic infections) |

How is CD4 count used?

CD4 counts are most often used, along with an HIV viral load, to evaluate the immune system of a person diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and to monitor effectiveness of antiretroviral treatment (ART or ARV), also called highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).

CD4 cells are types of white blood cells called T lymphocytes or T cells that fight infection and play an important role in immune system function. They are made in the thymus gland and they circulate throughout the body in the blood. (See the “What is being tested?” section for more details.)

CD4 cells are the main target of HIV. The virus enters the cells and uses them to make copies of itself (replicate) and spread throughout the body. HIV kills CD4 cells, so if an HIV infection is not treated, the number of CD4 cells will decrease as HIV infection progresses.

It is recommended that all individuals diagnosed with HIV infection receive antiretroviral treatment as soon as possible, including pregnant women, to reduce the risk of disease progression. People typically take at least three drugs from two different classes in order to prevent or minimize virus replication and the emergence of drug-resistant strains. Combinations of three or more antiretroviral drugs are referred to as highly active antiretroviral therapy or HAART.

Since CD4 cells are usually destroyed more rapidly than other types of lymphocytes and because absolute counts can vary from day to day, it is sometimes useful to look at the number of CD4 cells compared to the total lymphocyte count. The result is expressed as a percentage, i.e., CD4 percent.

The results can tell a health practitioner how strong a person’s immune system is and can help predict the risk of complications and debilitating opportunistic infections. CD4 counts are most useful when they are compared with results obtained from earlier tests. They are used in combination with the HIV viral load test, which measures the amount of HIV in the blood, to monitor how effective ART is in suppressing the virus and determine the risk of progression of HIV disease.

Sometimes, CD4 tests may be used along with a test for CD8 cells to help diagnose or monitor other conditions such as lymphoma, organ transplantation, and DiGeorge syndrome. CD8 cells are another type of lymphocyte that identify and kill cells that have been infected with viruses or that have been affected by cancer.

CD4 count clinical significance

CD4 count depletion is a consequence of HIV infection and leads to devastating opportunistic infections when left untreated. It affects both CD4 helper T cells in the lymphoid tissue as well as T cells circulating in the peripheral blood. In the natural history of HIV infection, there is an abrupt decline in the CD4 count during acute HIV infection that is usually followed by a rebound as a result of CD8 lymphocyte response to viral replication. Without antiretroviral treatment, the CD4 count will then decline over the next several years.

CD4 cell counts are used to monitor immunologic response to ART. With effective viral suppression, CD4 count is expected to increase by at least 50 cells/microliter after 4 to 8 weeks of treatment and by approximately 100 to 150 cells/microliters increase from baseline at one year. This is then followed by an expected increase of 50 to 100 cells/microliter per year. Several factors such as older age, lower CD4 baseline, and severe immunocompromised status have been associated with a less than expected improvement in the CD4 count while on treatment.

CD4 count is not a reliable indicator of virologic suppression and medication adherence. In patients who develop virologic resistance while on ART, it may take months for the CD4 count to decline and it may even initially increase. Several factors may falsely increase or decrease CD4 cell counts that may not necessarily reflect a patient’s true immunologic status. Inter-laboratory variability must also be taken into consideration. Thus, any significant but unexpected difference between two CD4 count measurements, which is defined as a 30% change in absolute CD4 count or 3% change in CD4 percentage, must be confirmed with a repeat testing.

What is a normal CD4 count

- CD4 count normal range: 500–1,400 cells per cubic millimeter (500–1,400 cells/mm³) 1

The CD4 count tends to be lower in the morning and higher in the evening. Acute illnesses, such as pneumonia, influenza, or herpes simplex virus infection, can cause the CD4 count to decline temporarily. Cancer chemotherapy can dramatically lower the CD4 count.

Low CD4 count

CD4 results are given as a number of cells per cubic millimeter of blood. Below is a list of typical results. Your results may vary depending on your health and even the lab used for testing. If you have questions about your results, talk to your health care provider.

- HIV CD4 count range: 250–500 cells per cubic millimeter (250–500 cells/mm³). It means you have a weakened immune system and may be infected with HIV.

- AIDS CD4 count range: 200 or fewer cells per cubic millimeter (<200 cells/mm³). It indicates AIDS and a high risk of life-threatening opportunistic infections. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considers people who have an HIV infection and CD4 counts below 200 cells/mm³ to have AIDS (stage III HIV infection), regardless of whether they have any signs or symptoms.

The CD4 count does not always reflect how someone with HIV disease feels and functions. For example, some people with higher CD4 counts are ill and have frequent complications, and some people with lower CD4 counts have few medical complications and function well.

While there is no cure for HIV, there are different medicines you can take to protect your immune system and can prevent you from getting AIDS. Today, people with HIV are living longer, with a better quality of life than ever before. If you are living with HIV, it’s important to see your health care provider regularly.

What are some common opportunistic infections I might get if I have an HIV infection?

Examples include fungal infections such as candidiasis and other infections such as tuberculosis or those caused by nontuberculosis mycobacteria. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides a table with examples of common opportunistic infections.

Table 2. Most common opportunistic infections for people living in the United States

| Candidiasis of bronchi, trachea, esophagus, or lungs | This illness is caused by infection with a common (and usually harmless) type of fungus called Candida. Candidiasis, or infection with Candida, can affect the skin, nails, and mucous membranes throughout the body. Persons with HIV infection often have trouble with Candida, especially in the mouth and vagina. However, candidiasis is only considered an OI when it infects the esophagus (swallowing tube) or lower respiratory tract, such as the trachea and bronchi (breathing tube), or deeper lung tissue. |

| Invasive cervical cancer | This is a cancer that starts within the cervix, which is the lower part of the uterus at the top of the vagina, and then spreads (becomes invasive) to other parts of the body. This cancer can be prevented by having your care provider perform regular examinations of the cervix |

| Coccidioidomycosis | This illness is caused by the fungus Coccidioides immitis. It most commonly acquired by inhaling fungal spores, which can lead to a pneumonia that is sometimes called desert fever, San Joaquin Valley fever, or valley fever. The disease is especially common in hot, dry regions of the southwestern United States, Central America, and South America. |

| Cryptococcosis | This illness is caused by infection with the fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. The fungus typically enters the body through the lungs and can cause pneumonia. It can also spread to the brain, causing swelling of the brain. It can infect any part of the body, but (after the brain and lungs) infections of skin, bones, or urinary tract are most common. |

| Cryptosporidiosis, chronic intestinal (greater than one month’s duration) | This diarrheal disease is caused by the protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium. Symptoms include abdominal cramps and severe, chronic, watery diarrhea. |

| Cytomegalovirus diseases (particularly retinitis) (CMV) | This virus can infect multiple parts of the body and cause pneumonia, gastroenteritis (especially abdominal pain caused by infection of the colon), encephalitis (infection) of the brain, and sight-threatening retinitis (infection of the retina at the back of eye). People with CMV retinitis have difficulty with vision that worsens over? time. CMV retinitis is a medical emergency because it can cause blindness if not treated promptly. |

| Encephalopathy, HIV-related | This brain disorder is a result of HIV infection. It can occur as part of acute HIV infection or can result from chronic HIV infection. Its exact cause is unknown but it is thought to be related to infection of the brain with HIV and the resulting inflammation. |

| Herpes simplex (HSV): chronic ulcer(s) (greater than one month’s duration); or bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis | Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a very common virus that for most people never causes any major problems. HSV is usually acquired sexually or from an infected mother during birth. In most people with healthy immune systems, HSV is usually latent (inactive). However, stress, trauma, other infections, or suppression of the immune system, (such as by HIV), can reactivate the latent virus and symptoms can return. HSV can cause painful cold sores (sometime called fever blisters) in or around the mouth, or painful ulcers on or around the genitals or anus. In people with severely damaged immune systems, HSV can also cause infection of the bronchus (breathing tube), pneumonia (infection of the lungs), and esophagitis (infection of the esophagus, or swallowing tube). |

| Histoplasmosis | This illness is caused by the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. Histoplasma most often infects the lungs and produces symptoms that are similar to those of influenza or pneumonia. People with severely damaged immune systems can get a very serious form of the disease called progressive disseminated histoplasmosis. This form of histoplasmosis can last a long time and involves organs other than the lungs. |

| Isosporiasis, chronic intestinal (greater than one month’s duration) | This infection is caused by the parasite Isospora belli, which can enter the body through contaminated food or water. Symptoms include diarrhea, fever, headache, abdominal pain, vomiting, and weight loss. |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) | This cancer, also known as KS, is caused by a virus called Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV) or human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8). KS causes small blood vessels, called capillaries, to grow abnormally. Because capillaries are located throughout the body, KS can occur anywhere. KS appears as firm pink or purple spots on the skin that can be raised or flat. KS can be life-threatening when it affects organs inside the body, such the lung, lymph nodes, or intestines. |

| Lymphoma, multiple forms | Lymphoma refers to cancer of the lymph nodes and other lymphoid tissues in the body. There are many different kinds of lymphomas. Some types, such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma, are associated with HIV infection. |

| Tuberculosis (TB) | Tuberculosis (TB) infection is caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis. TB can be spread through the air when a person with active TB coughs, sneezes, or speaks. Breathing in the bacteria can lead to infection in the lungs. Symptoms of TB in the lungs include cough, tiredness, weight loss, fever, and night sweats. Although the disease usually occurs in the lungs, it may also affect other parts of the body, most often the larynx, lymph nodes, brain, kidneys, or bones. |

| Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) or Mycobacterium kansasii, disseminated or extrapulmonary. Other Mycobacterium, disseminated or extrapulmonary. | MAC is caused by infection with different types of mycobacterium: Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, or Mycobacterium kansasii. These mycobacteria live in our environment, including in soil and dust particles. They rarely cause problems for persons with healthy immune systems. In people with severely damaged immune systems, infections with these bacteria spread throughout the body and can be life-threatening. |

| Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) | This lung infection, also called PCP, is caused by a fungus, which used to be called Pneumocystis carinii, but now is named Pneumocystis jirovecii. PCP occurs in people with weakened immune systems, including people with HIV. The first signs of infection are difficulty breathing, high fever, and dry cough. |

| Pneumonia, recurrent | Pneumonia is an infection in one or both of the lungs. Many germs, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi can cause pneumonia, with symptoms such as a cough (with mucous), fever, chills, and trouble breathing. In people with immune systems severely damaged by HIV, one of the most common and life-threatening causes of pneumonia is infection with the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae, also called Pneumococcus. There are now effective vaccines that can prevent infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae and all persons with HIV infection should be vaccinated. |

| Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy | This rare brain and spinal cord disease is caused by the JC (John Cunningham) virus. It is seen almost exclusively in persons whose immune systems have been severely damaged by HIV. Symptoms may include loss of muscle control, paralysis, blindness, speech problems, and an altered mental state. This disease often progresses rapidly and may be fatal. |

| Salmonella septicemia, recurrent | Salmonella are a kind of bacteria that typically enter the body through ingestion of contaminated food or water. Infection with salmonella (called salmonellosis) can affect anyone and usually causes a self-limited illness with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Salmonella septicemia is a severe form of infection in which the bacteria circulate through the whole body and exceeds the immune system’s ability to control it. |

| Toxoplasmosis of brain | This infection, often called toxo, is caused by the parasite Toxoplasma gondii. The parasite is carried by warm-blooded animals including cats, rodents, and birds and is excreted by these animals in their feces. Humans can become infected with it by inhaling dust or eating food contaminated with the parasite. Toxoplasma can also occur in commercial meats, especially red meats and pork, but rarely poultry. Infection with toxo can occur in the lungs, retina of the eye, heart, pancreas, liver, colon, testes, and brain. Although cats can transmit toxoplasmosis, litter boxes can be changed safely by wearing gloves and washing hands thoroughly with soap and water afterwards. All raw red meats that have not been frozen for at least 24 hours should be cooked through to an internal temperature of at least 150oF. |

| Wasting syndrome due to HIV | Wasting is defined as the involuntary loss of more than 10% of one’s body weight while having experienced diarrhea or weakness and fever for more than 30 days. Wasting refers to the loss of muscle mass, although part of the weight loss may also be due to loss of fat. |

What does the CD4 count test result mean?

A CD4 count is typically reported as an absolute level or count of cells (expressed as cells per cubic millimeter of blood). A normal CD4 count ranges from 500–1,200 cells/mm³ in adults and teens. Sometimes results are expressed as a percent of total lymphocytes (CD4 percent).

In general, a normal CD4 count means that the person’s immune system is not yet affected by HIV infection. A low CD4 count indicates that the person’s immune system has been affected by HIV and/or the disease is progressing. However, any single CD4 test result may differ from the last one even though the person’s health status has not changed. Usually, a health practitioner will take several CD4 test results into account rather than a single value and will evaluate the pattern of CD4 counts over time.

CD4 counts that rise and/or stabilize over time may indicate that the person is responding to treatment. If someone’s CD4 count declines over several months, a health practitioner may recommend starting prophylactic treatment for opportunistic infections such as Pneumocystis carinii (jiroveci) pneumonia (PCP) or candidiasis (thrush).

How to increase CD4 count

There’s no cure for HIV/AIDS, but many different drugs are available to control the virus. Such treatment is called antiretroviral therapy, or ART. Each class of drug blocks the virus in different ways. ART is now recommended for everyone, regardless of CD4 T cell counts. It’s recommended to combine three drugs from two classes to avoid creating drug-resistant strains of HIV.

The classes of anti-HIV drugs include:

- Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) turn off a protein needed by HIV to make copies of itself. Examples include efavirenz (Sustiva), etravirine (Intelence) and nevirapine (Viramune).

- Nucleoside or nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) are faulty versions of the building blocks that HIV needs to make copies of itself. Examples include Abacavir (Ziagen), and the combination drugs emtricitabine/tenofovir (Truvada), Descovy (tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine), and lamivudine-zidovudine (Combivir).

- Protease inhibitors (PIs) inactivate HIV protease, another protein that HIV needs to make copies of itself. Examples include atazanavir (Reyataz), darunavir (Prezista), fosamprenavir (Lexiva) and indinavir (Crixivan).

- Entry or fusion inhibitors block HIV’s entry into CD4 T cells. Examples include enfuvirtide (Fuzeon) and maraviroc (Selzentry).

- Integrase inhibitors work by disabling a protein called integrase, which HIV uses to insert its genetic material into CD4 T cells. Examples include raltegravir (Isentress) and dolutegravir (Tivicay).

When to start treatment

Everyone with HIV infection, regardless of CD4 T cell count, should be offered antiviral medication.

Treatment with HIV medicines (ART) is recommended for everyone with HIV. ART helps people with HIV live longer, healthier lives and reduces the risk of HIV transmission.

The Department of Health and Human Services guidelines 4 on the use of HIV medicines in adults and adolescents recommend that people with HIV start ART as soon as possible. In people with HIV who have certain conditions, it’s especially important to start ART right away.

HIV therapy is particularly important for the following situations:

- You have severe symptoms.

- You have an opportunistic infection.

- Your CD4 T cell count is under 350.

- You’re pregnant.

- You have HIV-related kidney disease.

- You’re being treated for hepatitis B or C.

- Early HIV infection

- AIDS

Pregnancy

All pregnant women with HIV should take HIV medicines to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. The HIV medicines will also protect the health of the pregnant woman.

All pregnant women with HIV should start taking HIV medicines as soon as possible during pregnancy. In general, women who are already taking HIV medicines when they become pregnant should continue taking HIV medicines throughout their pregnancies. When HIV infection is diagnosed during pregnancy, ART should be started right away.

AIDS

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is the most advanced stage of HIV infection. People with AIDS should start ART immediately.

A diagnosis of AIDS is based on the following criteria:

- A CD4 count less than 200 cells/mm³. A low CD4 count is a sign that HIV has severely damaged the immune system.

OR - Illness with an AIDS-defining condition. AIDS-defining conditions are infections and cancers that are life-threatening in people with HIV. Certain forms of lymphoma and tuberculosis are examples of AIDS-defining conditions.

Some illnesses that develop in people with HIV increase the urgency to start ART. These illnesses include HIV-related kidney disease and certain opportunistic infections. Opportunistic infections are infections that develop more often or are more severe in people with weakened immune systems, such as people with HIV.

Coinfection is when a person has two or more infections at the same time. Coinfection with HIV and certain other infections, such as hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus infection, increases the urgency to start ART.

Early HIV infection

Early HIV infection is the period up to 6 months after infection with HIV. During early HIV infection, the level of HIV in the body (called the viral load) is often very high. A high viral load damages the immune system and increases the risk of HIV transmission.

ART is an important part of staying healthy with HIV. Studies suggest that these benefits begin even when ART is started during early HIV infection. In addition, starting ART during early HIV infection reduces the risk of HIV transmission.

Treatment can be difficult

HIV treatment plans may involve taking several pills at specific times every day for the rest of your life. Each medication comes with its own unique set of side effects. It’s critical to have regular follow-up appointments with your doctor to monitor your health and treatment.

Some of the treatment side effects are:

- Nausea, vomiting or diarrhea

- Heart disease

- Weakened bones or bone loss

- Breakdown of muscle tissue (rhabdomyolysis)

- Abnormal cholesterol levels

- Higher blood sugar

Treatment for age-related diseases

Some health issues that are a natural part of aging may be more difficult to manage if you have HIV. Some medications that are common for age-related heart, bone or metabolic conditions, for example, may not interact well with anti-HIV medications. It’s important to talk to your doctor about your other health conditions and the medications you are taking.

Treatment response

Your doctor will monitor your viral load and CD4 T cell counts to determine your response to HIV treatment. CD4 T cell counts should be checked every three to six months.

Viral load should be tested at the start of treatment and then every three to four months during therapy. Treatment should lower your viral load so that it’s undetectable. That doesn’t mean your HIV is gone. It just means that the test isn’t sensitive enough to detect it.

References- Li R, Gossman WG. CD4 Count. [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470231

- Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1–Infected Adults and Adolescents, Table 4. Recommendations on the Indications and Frequency of Viral Load and CD4 Count Monitoring

- AIDS and Opportunistic Infections. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/livingwithhiv/opportunisticinfections.html

- Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents Living with HIV. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-arv-guidelines/37/whats-new-in-the-guidelines-