Cervical lymphadenopathy

Cervical lymphadenopathy is enlargement of the cervical lymph nodes or neck lymph nodes. Cervical lymph nodes drain the tongue, external ear, parotid gland, and deeper structures of the neck, including the larynx, thyroid, and trachea. Inflammation or direct infection of these areas causes subsequent engorgement and hyperplasia of their respective lymph node groups. Enlargement of the cervical lymph nodes commonly occurs with viral infections. These “reactive” lymph nodes are usually small, firm and non-tender and they may persist for weeks to months.

Cervical lymphadenopathy is a common problem in children and is usually related to infectious causes 1. In children with acute unilateral anterior cervical lymphadenitis and systemic symptoms, antibiotics may be prescribed. Empiric antibiotics should target Staphylococcus aureus and group A streptococci. Options include oral cephalosporins, amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin), orclindamycin 2. Corticosteroids should be avoided until a definitive diagnosis is made because treatment could potentially mask or delay histologic diagnosis of leukemia or lymphoma 3.

Cervical lymphadenopathy posterior to the sternocleidomastoid is typically a more ominous finding, with a higher risk of serious underlying disease 4.

Cervical adenopathy is a common feature of many viral infections. Infectious mononucleosis often manifests with posterior and anterior cervical adenopathy. Firm tender nodes that are not warm or erythematous characterize this lymph node enlargement. Other viral causes of cervical lymphadenopathy include adenovirus, herpesvirus, coxsackievirus, and cytomegalovirus (CMV). In herpes gingivostomatitis, impressive submandibular and submental adenopathy reflects the amount of oral involvement.

Bacterial infections cause cervical adenopathy by causing the draining nodes to respond to local infection or by the infection localizing within the node itself as a lymphadenitis. Bacterial infection often results in enlarged lymph nodes that are warm, erythematous, and tender. Localized cervical lymphadenitis typically begins as enlarged, tender, and then fluctuant nodes. The appropriate management of a suppurative lymph node includes both antibiotics and incision and drainage. Antibiotic therapy should always include coverage for Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes.

Also consider Kawasaki Disease – unilateral, >15mm, painful lymph nodes and other associated features.

Persistent enlargement of lymph nodes (> 2 weeks) may be caused by a number of other conditions:

- Atopic Eczema: Significant persistent enalargement may be associated with atopic eczema. These nodes are often more prominent in the posterior part of the neck and are usually bilateral.

- Malignancy:

- Lymphoma – Hodgkins and Non-Hodgkins lymphoma

- Leukemia – acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML),

- Rheumatologic conditions:

- Juvenile chronic arthritis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

In patients with cervical adenopathy, determine whether the patient has had recent or ongoing sore throat or ear pain. Examine the oropharynx, paying special attention to the posterior pharynx and the dentition. The classic manifestation of group A streptococcal pharyngitis is sore throat, fever, and anterior cervical lymphadenopathy. Other streptococcal infections causing cervical adenopathy include otitis media, impetigo, and cellulitis.

Atypical mycobacteria cause subacute cervical lymphadenitis, with nodes that are large and indurated but not tender. The only definitive cure is removal of the infected node 5.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis may manifest with a suppurative lymph node identical to that of atypical mycobacterium. Intradermal skin testing may be equivocal. A biopsy may be necessary to establish the diagnosis.

Catscratch disease, caused by Bartonella henselae, presents with subacute lymphadenopathy often in the cervical region. The disease develops after the infected pet (usually a kitten) inoculates the host, usually through a scratch. Approximately 30 days later, fever, headache, and malaise develop, along with adenopathy that is often tender. Several lymph node chains may be involved. Suppurative adenopathy occurs in 10-35% of patients. Antibiotic therapy has not been shown to shorten the course.

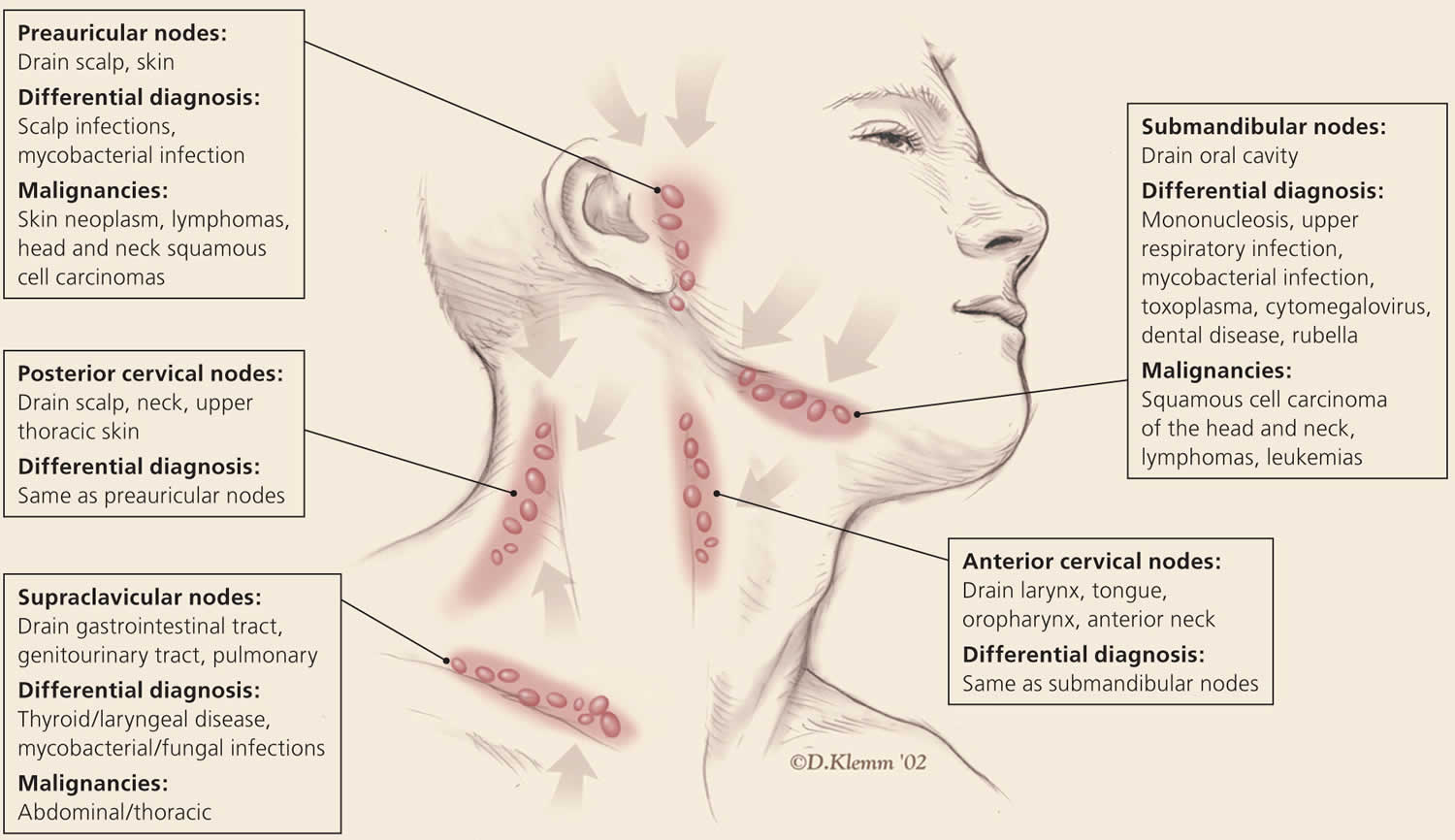

Figure 1. Cervical lymphadenopathy

[Source 6 ]Cervical lymphadenopathy causes

Infection is a common cause of head and cervical lymphadenopathy 6. In children, acute and self-limiting viral illnesses are the most common causes of lymphadenopathy 7. Inflamed cervical nodes that progress quickly to fluctuation are typically caused by staphylococcal and streptococcal infections and require antibiotic therapy with occasional incision and drainage. Persistent lymphadenopathy lasting several months can be caused by atypical mycobacteria, cat-scratch disease, Kikuchi lymphadenitis, sarcoidosis, and Kawasaki disease, and often can be mistaken for neoplasms 8. Supraclavicular adenopathy in adults and children is associated with high risk of intra-abdominal malignancy and must be evaluated promptly. Studies found that 34% to 50% of these patients had malignancy, with patients older than 40 years at highest risk 9.

Infections

- Infectious mononucleosis (EBV), cytomegalovirus – may have generalised lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly.

- Mycobacterium avium complex – Adenoapthy is usually unilateral and most cases occur in the under 5-year age group. Non-tender, slightly fluctuant node, which may become tethered to underlying structures. Violaceous hue to the overlying skin is sometimes seen. Systemically well. Usually not immunocompromised.

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis – non-tender nodes. History of exposure. Systemic symptoms of fever, malaise, weight loss.

- Cat Scratch Disease (Bartonella henselae) – tender, usually axillary, nodes. History of a cat scratch or lick 2 weeks prior. There may be a papule at the site.

- Toxoplasma gondii – generalised lymphadenopathy. Systemic features of fatigue or myalgia.

- HIV

Acute bacterial adenitis is characterized by larger nodes >10mm, which are tender and may be fluctuant. Most typically these are in the anterior part of the neck. There is often associated fever and warm, erythematous overlying skin. The majority are caused by Staphylococcus Aureus or Group A Streptococcus (Strep pyogenes). A site of entry may be found e.g. mouth or scalp. Anaerobic bacteria may be associated with dental disease in older children.

Noninfectious causes

- Malignant childhood tumors develop in the head and neck region in one quarter of cases. In the first 6 years of life, neuroblastoma, leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma (in order of decreasing frequency) are most common in the head and neck region. In children older than 6 years, Hodgkin disease and non-Hodgkin lymphoma both predominate. Children with Hodgkin disease present with cervical adenopathy in 80-90% of cases as opposed to 40% of those with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

- Kawasaki disease is an important cause of cervical adenopathy. These children have fever for at least 5 days, and cervical lymphadenopathy is one of the 5 diagnostic criteria (of which 4 are necessary to establish the diagnosis).

Cervical lymphadenopathy diagnosis

The laboratory evaluation of lymphadenopathy must be directed by the history and physical examination and is based on the size and other characteristics of the nodes and the overall clinical assessment of the patient. When a laboratory evaluation is indicated, it must be driven by the clinical evaluation 10.

The following studies should be considered for chronic lymphadenopathy (>3 wk):

- CBC count, including a careful evaluation of the peripheral blood smear

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and uric acid

- Bartonella henselae (catscratch) serology if exposed to a cat

- Tuberculosis skin test (TST) and interferon-gamma release assay (eg, Quantiferon Gold)

- Evaluation of hepatic and renal function and a urine analysis are useful in identifying underlying systemic disorders that may be associated with lymphadenopathy. When evaluating specific regional adenopathy, lymph node aspirate for culture may be important if lymphadenitis is clinically suspected.

- Titers for specific microorganisms may be indicated, particularly if generalized adenopathy is present. These may include Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Toxoplasma species, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- Chest radiography

- Radiologic evaluation with computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasonography may help to characterize lymphadenopathy. The American College of Radiology recommends ultrasonography as the initial imaging choice for cervical lymphadenopathy in children up to 14 years of age and computed tomography for persons older than 14 years 11. Based on the location of the abnormal nodes, the sensitivity of these modalities for diagnosing metastatic lymph nodes varies; therefore, history and clinical examination must guide selection 12. If the diagnosis is still uncertain, biopsy is recommended.

Biopsy

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and core needle biopsy can aid in the diagnostic evaluation of lymph nodes when etiology is unknown or malignant risk factors are present 13. Fine-needle aspiration cytology is a quick, accurate, minimally invasive, and safe technique to evaluate patients and aid in triage of unexplained lymphadenopathy 14. If a reactive lymph node is likely, core needle biopsy can be avoided, and fine-needle aspiration used alone. Combined, they allow cytologic and histopathologic assessment of lymph nodes. However, the use of both techniques may not be needed because the diagnostic accuracy of fine-needle aspiration in adult populations has been reported to approach 90%, with a sensitivity and specificity of 85% to 95% and 98% to 100%, respectively 15. False-positive diagnoses are rare with fine-needle aspiration. False-negative results occur secondary to early or partial involvement of lymph nodes, inexperience with lymph node cytology, unrecognized lymphomas with heterogeneity, and sampling errors 16. There are concerns about the reliability of fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of diseases such as lymphoma because it is unable to assess lymph node architecture. Regardless, fine-needle aspiration may be a useful triage tool for differentiating benign reactive lymphadenopathy from malignancy 17.

Cervical lymphadenopathy treatment

Treatment is determined by the specific underlying cause of lymphadenopathy.

Most clinicians treat children with cervical lymphadenopathy conservatively. Antibiotics should be given only if a bacterial infection is suspected. This treatment is often given before biopsy or aspiration is performed. This practice may result in unnecessary prescription of antimicrobials. However, the risks of surgery often outweigh the potential benefits of a brief course of antibiotics. Most enlarged lymph nodes are caused by an infectious process. If aspects of the clinical picture suggest malignancy, such as persistent fevers or weight loss, biopsy should be pursued sooner.

Management of superior vena cava syndrome requires emergency care, including chemotherapy and possibly radiation therapy.

Management of acute cervical lymphadenitis

Fluctuant cervical lymph node

- Incision and drainage (contraindicated in suspected TB as may result in sinus formation)

Child is well – oral antibiotics for 10 days, with review in 48 hours.

- Flucloxacillin 25 mg/kg four times daily

- Hypersensitivity to penicillin: Cephalexin 25 mg/kg (up to 500mg) three times daily

- Severe penicillin hypersensitivity: Erythromycin 15 mg/kg (up to 500mg) three times daily

Neonates, unwell or failed oral oral antibiotics – IV antibiotics

- Flucloxacillin 50 mg/kg up to 2 g 6-hourly

- Hypersensitive to penicillin: Cephazolin 25 mg/kg up to 2g IV 6 hourly

- Severe penicillin hypersensitivity: Clindamycin 10mg/kg up to 450mg 6hourly

- Leung AK, Davies HD. Cervical lymphadenitis: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009 May. 11(3):183-9.

- Meier JD, Grimmer JF. Evaluation and management of neck masses in children. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(5):353–358.

- Pangalis GA, Vassilakopoulos TP, Boussiotis VA, Fessas P. Clinical approach to lymphadenopathy. Semin Oncol. 1993;20(6):570–582.

- Lymphadenopathy Clinical Presentation. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/956340-clinical

- Lindeboom JA, Kuijper EJ, Bruijnesteijn van Coppenraet ES, Lindeboom R, Prins JM. Surgical excision versus antibiotic treatment for nontuberculous mycobacterial cervicofacial lymphadenitis in children: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Apr 15. 44(8):1057-64.

- Unexplained Lymphadenopathy: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Dec 1;94(11):896-903. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2016/1201/p896.html

- Bazemore AW, Smucker DR. Lymphadenopathy and malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(11):2103–2110.

- Rajasekaran K, Krakovitz P. Enlarged neck lymph nodes in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60(4):923–936.

- Rosenberg TL, Nolder AR. Pediatric cervical lymphadenopathy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2014;47(5):721–731.

- Twist CJ, Link MP. Assessment of lymphadenopathy in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002 Oct. 49(5):1009-25.

- American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria: neck mass/adenopathy. https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69504/Narrative

- Dudea SM, Lenghel M, Botar-Jid C, Vasilescu D, Duma M. Ultrasonography of superficial lymph nodes: benign vs. malignant. Med Ultrason. 2012;14(4):294–306.

- King D, Ramachandra J, Yeomanson D. Lymphadenopathy in children: refer or reassure? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2014;99(3):101–110.

- Monaco SE, Khalbuss WE, Pantanowitz L. Benign non-infectious causes of lymphadenopathy: a review of cytomorphology and differential diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40(10):925–938.

- Lioe TF, Elliott H, Allen DC, Spence RA. The role of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in the investigation of superficial lymphadenopathy; uses and limitations of the technique. Cytopathology. 1999;10(5):291–297.

- Thomas JO, Adeyi D, Amanguno H. Fine-needle aspiration in the management of peripheral lymphadenopathy in a developing country. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;21(3):159–162.

- Metzgeroth G, Schneider S, Walz C, et al. Fine needle aspiration and core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of lymphadenopathy of unknown aetiology. Ann Hematol. 2012;91(9):1477–1484.