Cricopharyngeal myotomy

Cricopharyngeal myotomy is a surgical procedure in which the cricopharyngeus muscle also known as the upper esophageal sphincter, which makes a “ring” around the upper esophagus, is divided or cut across in order to break its grip 1. A cricopharyngeal myotomy is done in cases where the cricopharyngeus muscle (i.e., the upper esophageal sphincter) fails to relax when one swallows (also known as cricopharyngeal dysfunction), resulting in a functional obstruction and dysphagia. Cricopharyngeal dysfunction is a disorder caused by failure of the cricopharyngeus muscle in upper esophageal sphincter to relax during swallowing and thereby causing oropharyngeal dysphagia 2.

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction or achalasia may be primary or secondary. Primary achalasia refers to persistent spasm or failure of the cricopharyngeus muscle to relax, where the pathology is confined to the muscle and there is no underlying neurologic or systemic cause. Primary achalasia may be idiopathic or be associated with intrinsic disorders of the muscle e.g.polymyositis, muscular dystrophy, and hypothyroidism. Cricopharyngeal spasm may be secondary to neurologic disorders e.g.poliomyelitis, oculopharyngeal dysphagia, stroke, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), diabetic neuropathy, myasthenia gravis, and peripheral neuropathies. Cricopharyngeal dysfunction also can be seen alone or in combination with a Zenker’s diverticulum.

Symptoms of cricopharyngeal dysfunction include dysphagia, with solids more so than with liquids. If a Zenker’s diverticulum is present, the patient may also experience late “regurgitation” of undigested food retained for hours or longer in the sac.

The diagnosis is made on history and contrast swallow(videofluoroscopy). The contrast swallow typically shows a prominent bulge in the posterior wall of the proximal esophagus due to contraction of the cricopharyngeus muscle.

Cricopharyngeal myotomy is often used for the management of upper esophageal and pharyngeal dysphagia in the setting of polio, degenerative neurologic disorders, and strokes and after head and neck surgery.

Open cricopharyngeal myotomy, performed through a cervical approach, has been successful in relieving oropharyngeal dysfunction resulted dysphagia in a variety of structural, myogenic, neurogenic, and idiopathic disorders 2. Cricopharyngeal myotomy also provides longer relieve on oropharyngeal dysfunction than botox (botulinum toxin) injection which is common alternative treatment option 3.

First, in patients in whom the diagnosis of cricopharyngeal achalasia may be in question, botulinum toxin treatment can be used as a trial of therapy. If the patient’s dysphagia symptoms resolve after botulinum toxin injection, the diagnosis of cricopharyngeal achalasia is confirmed, and subsequent cricopharyngeal myotomy may be deemed appropriate.

In addition, patients who are medically infirm and cannot undergo external cricopharyngeal myotomy may be considered for botulinum toxin therapy. Unfortunately, the administration of the botulinum toxin into the cricopharyngeus is technically difficult and somewhat uncomfortable for the patient. Furthermore, because the effective botulinum toxin is temporary, patients are required to undergo repeat injections to maintain therapeutic efficacy. Finally, inadvertent injection outside the cricopharyngeus may result in temporary paralysis of the laryngeal musculature, causing dysphonia and, rarely, aspiration.

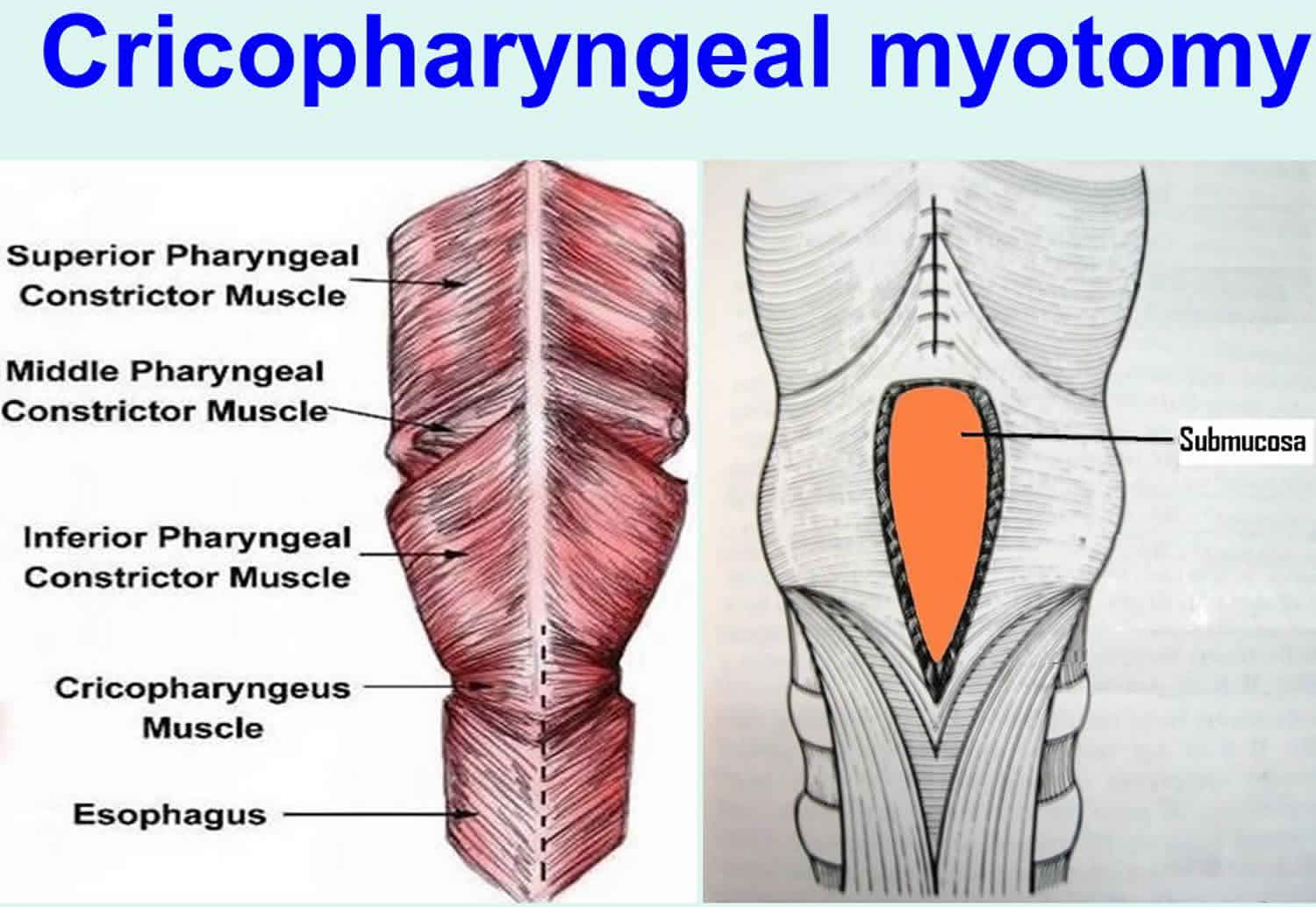

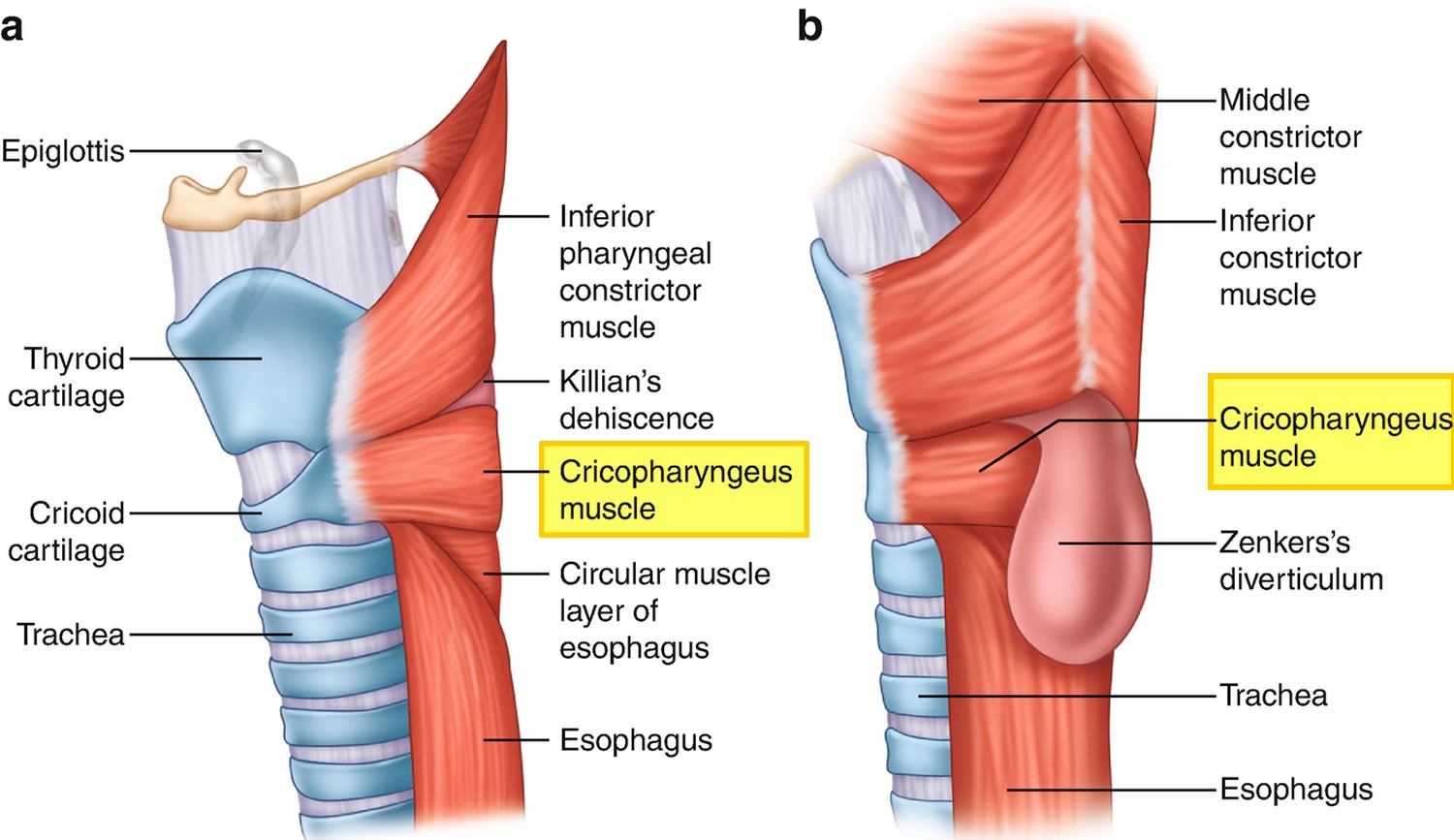

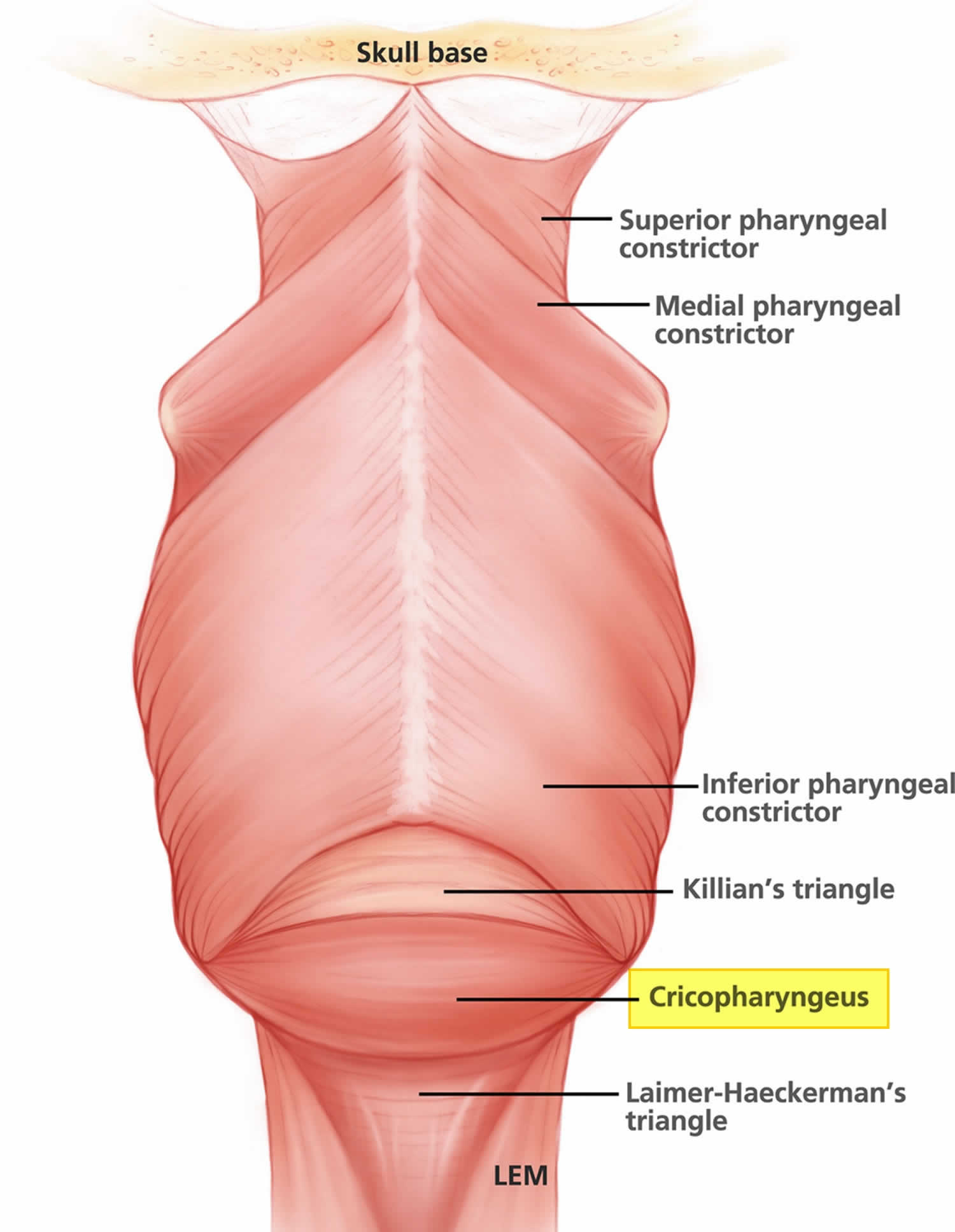

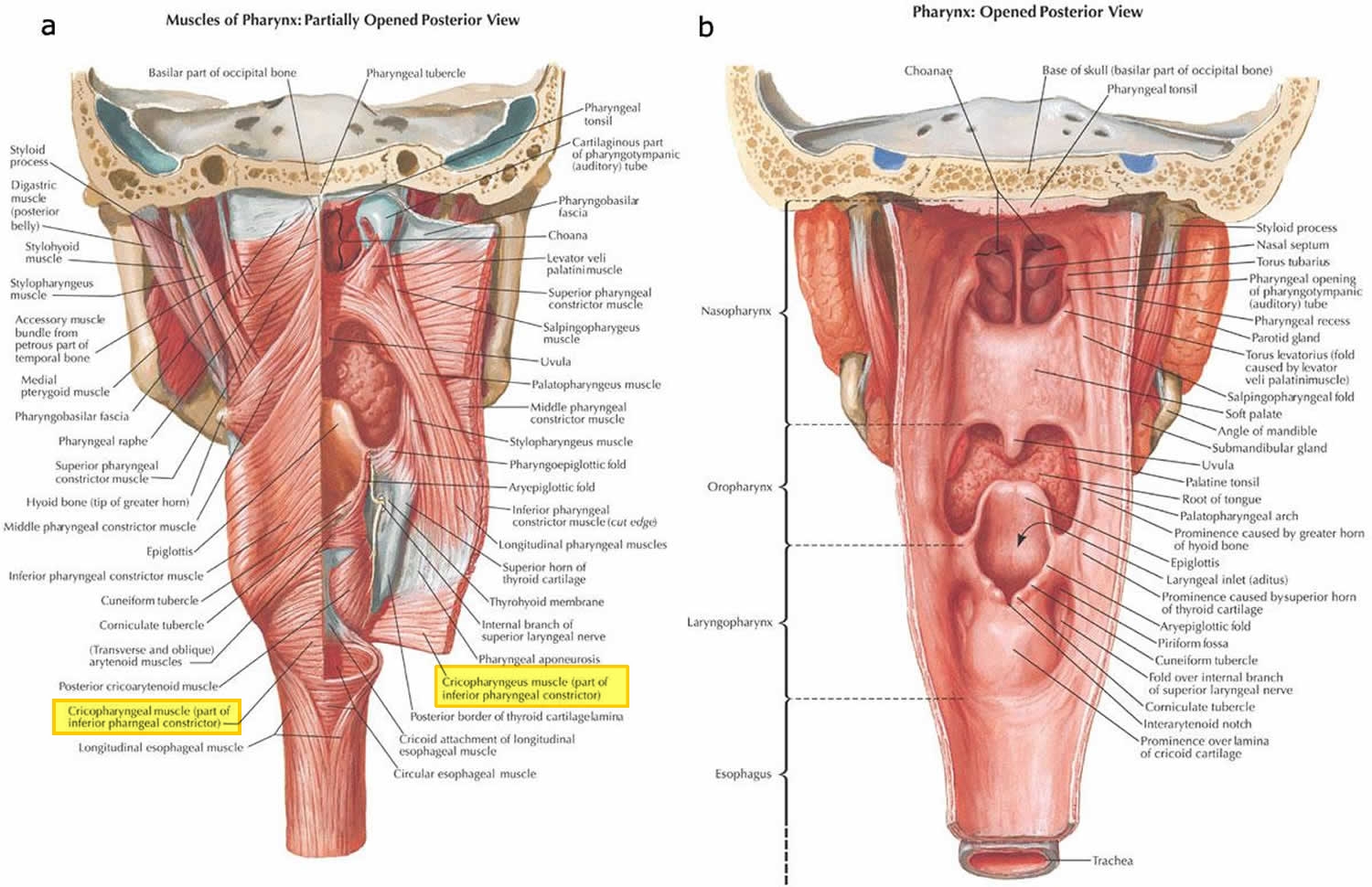

Cricopharyngeus muscle anatomy

The cricopharyngeus muscle is a true sphincter composed of striated muscle (Figure 1). Arising from the lateral borders of the cricoid cartilage, the muscle fibers form a sling around the wall of the superior aspect of the cervical esophagus. The cricopharyngeus muscle is bordered superiorly by the inferior constrictor muscle and merges inferiorly with the muscular layers of the cervical esophagus. The muscle is innervated primarily by the vagus nerve, both by branches from the pharyngeal plexus and by neuronal branches from the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Therefore, the recurrent laryngeal nerves lie in close proximity within the surgical.

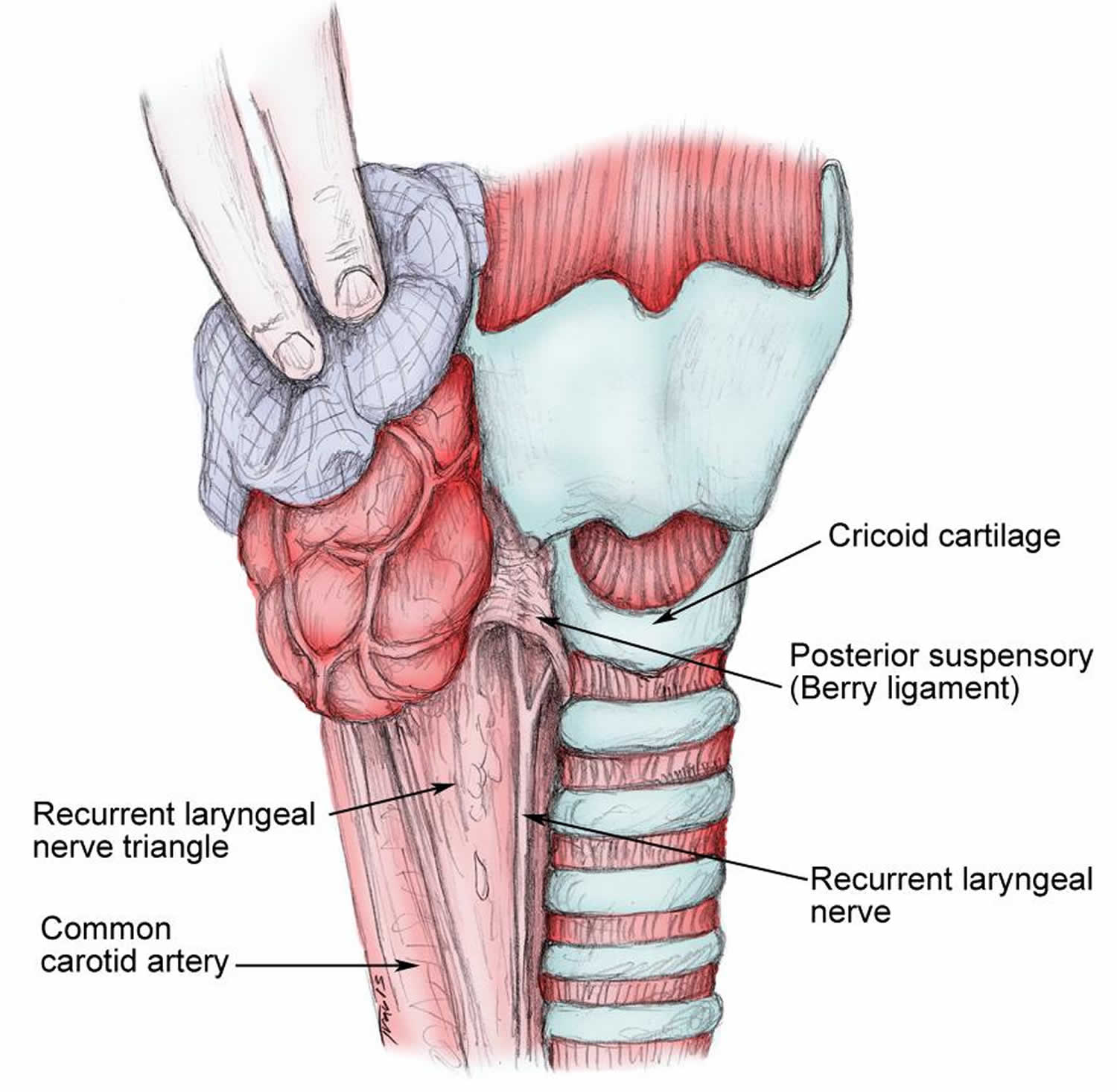

The main trunk of the recurrent laryngeal nerve lies in a triangle bound laterally by the common carotid artery, the internal jugular vein, and the vagus nerve and medially by the trachea and esophagus. The recurrent nerve passes under the posterior suspensory ligament of Berry (located on either side of the trachea, extending from the cricoid cartilage and the first 2 tracheal rings to the posteromedial aspect of the thyroid gland), before entering the larynx (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Cricopharyngeus muscle anatomy

Figure 2. Relation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve to the cricoid cartilage

Cricopharyngeal myotomy indications

The indications for cricopharyngeal myotomy in the treatment of cervical dysphagia are usually based on a combination of patient symptoms, findings from radiologic studies, and less frequently, manometric information 4. Before surgical intervention, if possible, aggressively manage underlying etiologies such as neurologic disorders and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Myotomy may be considered if conservative measures fail and radiologic evidence exists on the video fluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) of cricopharyngeal dysfunction that leads to a hesitation of bolus passage.

Manometry may also lend some information, and those patients with clear-cut cricopharyngeal spasm with manometric evidence of hypertonic contraction of the cricopharyngeus muscle tend to have better outcomes. Cricopharyngeal myotomy may also be considered in the absence of clear-cut radiologic data when patients present with significant aspiration or weight loss caused by clinically evident cervical dysphagia, especially when other methods of treatment have failed.

Cricopharyngeal myotomy contraindications

Cricopharyngeal myotomy is contraindicated when the patient has a known tumor that involves the cervical esophagus or an otherwise correctable mucosal disease that involves the cervical esophagus or hypopharynx. Cricopharyngeal myotomy is also relatively contraindicated in patients who have undergone radiation therapy for head and neck cancer because the cricopharyngeus may be fibrotic and less apt to release when sectioned. Other authors consider cricopharyngeal myotomy to be relatively contraindicated in patients with progressive neurologic disorders such as bulbar palsy.

Traditionally, cricopharyngeal myotomy has been thought to afford limited success in the setting of oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. However, recent data suggest that it can be effective for several years after surgery with acceptable rates of recurrent dysphagia at 3 years 5. Finally, cricopharyngeal myotomy may also be relatively contraindicated in the setting of significant gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Although this is controversial, massive reflux may predispose the patient to significant laryngopharyngitis and subsequent dysphonia.

Cricopharyngeal myotomy procedure

The classic approach is the external cricopharyngeal myotomy technique. This procedure may be performed with the patient under local or general anesthesia. Position the patient supine on the operating room table. After induction of anesthesia, intubate the cervical esophagus with a relatively large endotracheal tube to provide internal distention of the cervical esophagus at the time of the myotomy. Traditionally, a left-sided surgical approach is used. Make the skin incision in a favorable cervical skin crease roughly overlying the cricoid cartilage. Elevate the subplatysmal skin flaps superiorly and inferiorly to provide exposure to both the superior and inferior limits of the cricopharyngeus, and place self-retaining retractors. Identify the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and reflect it posteriorly to expose the carotid sheath. Develop a plane between the structures of the carotid sheath and the laryngotracheal complex with the greatvesselssubsequently being reflectedposteriorly.

Often, the omohyoid muscle is sectioned to provide additional exposure. Take care to protect the recurrent laryngeal nerve as it enters behind the ala of the thyroid cartilage. Rotate the larynx anteriorly into the right, bringing the internally distended cervical esophagus into view. The cricopharyngeus fibers are seen as a fan-shaped band that emanates from the posterior lateral border of the cricoid cartilage. Magnification with surgical loupes is often helpful in identifying these muscle fibers, which may blend into the surrounding submucosa. Sequentially cut the cricopharyngeus fibers with a sharp No-15 or No-10 blade until the mucosa is seen. Often, when all of the muscle fibers have been appropriately sectioned, the surgeon can see the writing on the endotracheal tube. Many authors have emphasized that the cricopharyngeal myotomy must be extended superiorly and inferiorly to ensure that all of the muscle has been released. This often translates into a myotomy length of 4-5 cm.

Some authors also advocate removing a 3- to 4-mm strip of muscle along the length of the myotomy or elevating and suturing the cut edge of muscle back onto itself. These additional techniques have been advocated to prevent reattachment and subsequent persistent cricopharyngeal dysfunction.

At the conclusion of the procedure, irrigate the wound and place and secure a standard closed suction drain system. Reapproximate the platysma in a watertight fashion. Close the skin according to surgeon preference. Remove the esophageal endotracheal tube before extubation.

Recently, investigators have been exploring a trans-oral approach for endoscopic cricopharyngeal myotomy. However, only limited case series have been published, and follow-up data are rather limited. Initial data suggest that this technique may have applications when the technique is refined and longer follow-up is available. Also, an endoscopic approach has the advantages of avoiding an external neck incision and, to some degree, less risk to surrounding structures 6. Recent data examining operative and postoperative outcomes for endoscopic versus open cricopharyngeal myotomy techniques have demonstrated similar success rates between the two techniques with improvements in surgical time and postoperative outcomes in the endoscopic group 7.

Endoscopic cricopharyngeal myotomy

Other authors have reported on limited patient series that describe individuals who have undergone cricopharyngeal myotomy via an endoscopic technique. Using the potassium titanyl phosphate laser, investigators have successfully sectioned the cricopharyngeus muscle via the endoscope, obviating the need for an external incision. However, these clinical series are quite small, and follow-up data to this point are limited. In a recent series of 29 patients (mean age 62 years) after a mean follow-up of 18 months, investigators reported on the use of the CO2 laser to section the cricopharyngeus muscle endoscopically. Patients reported a significant subjective improvement in swallowing function, although not according to a validated scale. Similar corresponding radiographic improvements were noted based on swallowing videofluoroscopy. No complications were noted. Thus, with further confirmatory studies, an endoscopic laser myotomy approach may be feasible.

Several recent series that also had small sample sizes suggested that an endoscopic approach is feasible and safe. However, more long-term follow-up data are seriously lacking with respect to the effectiveness of the procedure, especially as it compares with the open cricopharyngeal myotomy approach. Investigators have also adapted the endoscopic approach to cricopharyngeal myotomy for those patients with swallowing dysfunction after extensive resection of oral and pharyngeal cancer. Such a procedure may improve dysphagia in up to 80% of those suffering from cricopharyngeal dysfunction and dysphagia after extensive resection of oral or oral pharyngeal cancer 8.

Cricopharyngeal myotomy recovery

Patients are usually observed in the hospital for one night following the procedure. Patients may initiate a standard oral diet the night of the procedure and advance as tolerated. The closed suction drain is usually removed on postoperative day 1, and the patient is discharged home.

Follow-up

Patients are usually seen in routine postoperative follow-up care at 1 week postsurgery for a surgical wound check. In addition to the subjective evaluation of the patients’ self-reported swallowing symptoms and improvement, patients also may undergo a follow-up VFSS to objectively assess the impact of the cricopharyngeal myotomy on the cervical dysphagia. Follow-up testing is particularly important in elderly, frail, and pulmonary insufficient patients, particularly when a preoperative history of aspiration exists. Recent follow-up radiologic data suggest that patients with cricopharyngeal dysfunction may continue to have pharyngeal stasis with dysphagia implications after surgery.

Cricopharyngeal myotomy complications

Patients with a myogenic cause for their cricopharyngeal dysfunction have a higher rate of postoperative complications after cricopharyngeal myotomy, including pulmonary aspiration and lethal respiratory distress. Such patients should be identified and placed under increasing surveillance postoperatively.

The most common complication of external cricopharyngeal myotomy is inadvertent entry into the lumen of the cervical esophagus. Although thoroughly sectioning the entire cricopharyngeus muscle is important, the margin for error is small because the esophageal submucosa and mucosa are very thin. If the cervical esophageal lumen is entered, repair it with a watertight closure in a single layer. Avoid a double-layer closure because it may predispose the patient to stenosis in this area, defeating the original purpose of the procedure. In the setting of an inadvertent esophagotomy, maintain wound drainage and monitor the patient for evidence of salivary fistula through the drain site. Maintain perioperative and postoperative antibiotics to cover oral flora. If no evidence of air leakage or salivary fistula is present, the patient may resume a gradually advancing diet on postoperative day 3, with anticipated discharge 1-2 days later.

Other complications may occur during cricopharyngeal myotomy. A relatively uncommon occurrence is injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which most often manifests as hoarseness after extubation and most often is due to a stretch injury to the nerve. Most injuries such as this resolve with time; however, recovery may require several months. During the recovery phase, monitor the patient for aspiration and pulmonary complications. If the main trunk of the recurrent laryngeal nerve is accidentally sectioned during the procedure, perform a primary neural anastomosis. If this occurs, the patient will likely have a permanent vocal cord weakness that results in dysphonia. This may be rehabilitated with vocal cord augmentation techniques or medialization thyroplasty.

Overall complication rates after cricopharyngeal myotomy are relatively small considering the generalized poor nutrition of many patients preoperatively. Pulmonary complications occur relatively commonly (5-10% of patients), particularly in those who suffer from myogenic cricopharyngeal dysfunction. Nine percent of patients may exhibit a transient fluid collections/inflammation in the retro pharyngeal space and 1.2% of patients may develop frank fistula formation 9.

Cricopharyngeal myotomy prognosis

Reported success rates for cricopharyngeal myotomy and management of cervical dysphagia vary widely. To some degree, this variability may be caused by differences in the patient populations that undergo myotomy. Although some studies report results in patients who undergo cricopharyngeal myotomy for neuromuscular disease, other studies report on cricopharyngeal myotomy as a treatment of idiopathic cervical dysphagia. In properly selected patients, success rates that approach 75% may be expected. The chance of success usually decreases when an underlying neuromuscular disorder is present.

The one exception is found in patients with oculopharyngeal dysphagia; these patients generally have a good result from myotomy alone. More recently, reasonably positive outcomes have been achieved by treating patients who have oculopharyngeal dysphagia with simple repeated dilatation of the upper esophageal sphincter. Furthermore, patients with dysphagia secondary to inclusion body myositis within the cricopharyngeus muscle also have a relatively poorer prognosis than those with other causes for cricopharyngeal dysfunction 10.

In general, the prognosis for dysphagia without treatment is unfavorable; few patients demonstrate spontaneous improvement in their cervical dysphagia. This forces many patients to opt for a chance of cure with surgery. Untreated patients with inclusion body myositis, for example, will often progress to death from aspiration pneumonia.

References- Neuromuscular Disorders: Treatment and Management 2010 ISBN 978-1-4377-0372-6 https://doi.org/10.1016/C2009-0-39341-1

- Jain V, Bhatnagar V. Cricopharyngeal myotomy for the treatment of cricopharyngeal achalasia. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:1656–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.04.031

- Sung A, Lee KW. Cricopharyngeal myotomy for delayed Cricopharyngeal dysfunction after head and neck surgery – case report. BMC Surg. 2020;20(1):6. Published 2020 Jan 8. doi:10.1186/s12893-019-0667-5 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6951019

- Cricopharyngeal Myotomy. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/836966-overview

- Coiffier L, Perie S, Laforet P, Eymard B, St Guily JL. Long-term results of cricopharyngeal myotomy in oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006 Aug. 135(2):218-22.

- Ho AS, Morzaria S, Damrose EJ. Carbon dioxide laser-assisted endoscopic cricopharyngeal myotomy with primary mucosal closure. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011 Jan. 120(1):33-9.

- Huntley C, Boon M, Spiegel J. Open vs. endoscopic cricopharyngeal myotomy; Is there a difference?. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017 Jul – Aug. 38 (4):405-407.

- Pitman M, Weissbrod P. Endoscopic CO2 laser cricopharyngeal myotomy. Laryngoscope. 2009 Jan. 119(1):45-53.

- Brigand C, Ferraro P, Martin J, Duranceau A. Risk factors in patients undergoing cricopharyngeal myotomy. Br J Surg. 2007 Aug. 94(8):978-83.

- Oh TH, Brumfield KA, Hoskin TL, Kasperbauer JL, Basford JR. Dysphagia in inclusion body myositis: clinical features, management, and clinical outcome. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008 Nov. 87(11):883-9.