Descending perineum syndrome

Descending perineum syndrome is when the perineum (the area between the anus and the scrotum/vulva) bulges down and prolapses below the bony outlet of the pelvis. Parks et al. 1 in 1966 defined perineal descent syndrome as descent of the anal margin under the line passing through the ischial tuberosity on clinical examination 2 and is characterized by swelling of the perineum. Perineal descent syndrome is often associated with chronic straining in patients with a history of chronic straining and a sensation of incomplete defecation which is sometimes followed by a feeling of obstruction. There can also be complaints of anal bleeding, loss of mucus, perineal pruritus or pain. Sometimes digital maneuvers are required to pass stool 3 and severe cases are often associated with anal incontinence 3. Other conditions that weaken the pelvic floor musculature can also lead to symptomatic perineal descent. Some amount of perineal descent is often present in conjunction with pelvic organ prolapse. Common symptoms of descending perineum syndrome include the need to press up on the perineum to aid with bowel movements and the feeling of the pelvis “dropping” with weight bearing activity. Only 14% of patients with descending perineum syndrome will be symptomatic with coloproctologic symptoms such as constipation, obstructive disease syndrome and incomplete bowel emptying which frequently requires digital maneuvers 4. Such a combination is defined as Descending Perineum Syndrome 5.

Descending perineum syndrome can deteriorate over the years, progressing from isolated obstructive disease syndrome to fecal incontinence which can lead to a vicious cycle: the more straining, the more stretching of the levator ani muscle with aggravation of obstructive disease syndrome.

Perineal descent syndrome is well described by Parks in 1966 1. For this author this title is mainly descriptive, as perineal descent on straining is both the cause of symptoms and the most obvious physical sign. For Parks 1, the main symptoms of perineal descent syndrome are dyschesia (partial and intermittent obstruction by the anterior rectal wall), pain (dull aching pain in the perineum or sacrum after defecation), bleeding or passage of mucus (prolapse of the anterior rectal wall) and anal leakage. The physical signs of this syndrome on external examination are a low position of the anus at rest or a perineal descent on straining (more than 3 cm). During this straining, the anal mucosa may pout. On rectal examination, during straining, the pubo-rectalis descends sharply and the anterior rectal wall pushes down on the examining finger. Muscle tone is easily overcome by posterior traction.

Although descending perineum syndrome has been described in the literature for many decades, it is still uncommonly diagnosed and difficult to manage 6. Perineal descent syndrome treatment begins with identifying and addressing the underlying cause. As mentioned above, constipation and the need to chronically strain is often identified and treated. Pelvic floor physical therapy to strengthen the floor of the pelvis can sometimes be utilized to help symptoms. If surgery is performed, the focus is on elevation of the perineum and pelvic floor with either a da Vinci Sacrocolpoperineopexy or a posterior vaginal mesh placement with perineorrhaphy and elevation of the perineum. The choice of surgery depends on the presence of other conditions such as cystocele, rectocele, or uterine prolapse and on the severity of symptoms.

Chronic constipation and perineal descent may co-exist with rectal prolapse. If rectal prolapse is present, rectopexy is performed with sacrocolpoperineopexy. Bowel and fecal incontinence also may be associated with perineal descent if the perineal body is weak and is treated by anal sphincteroplasty.

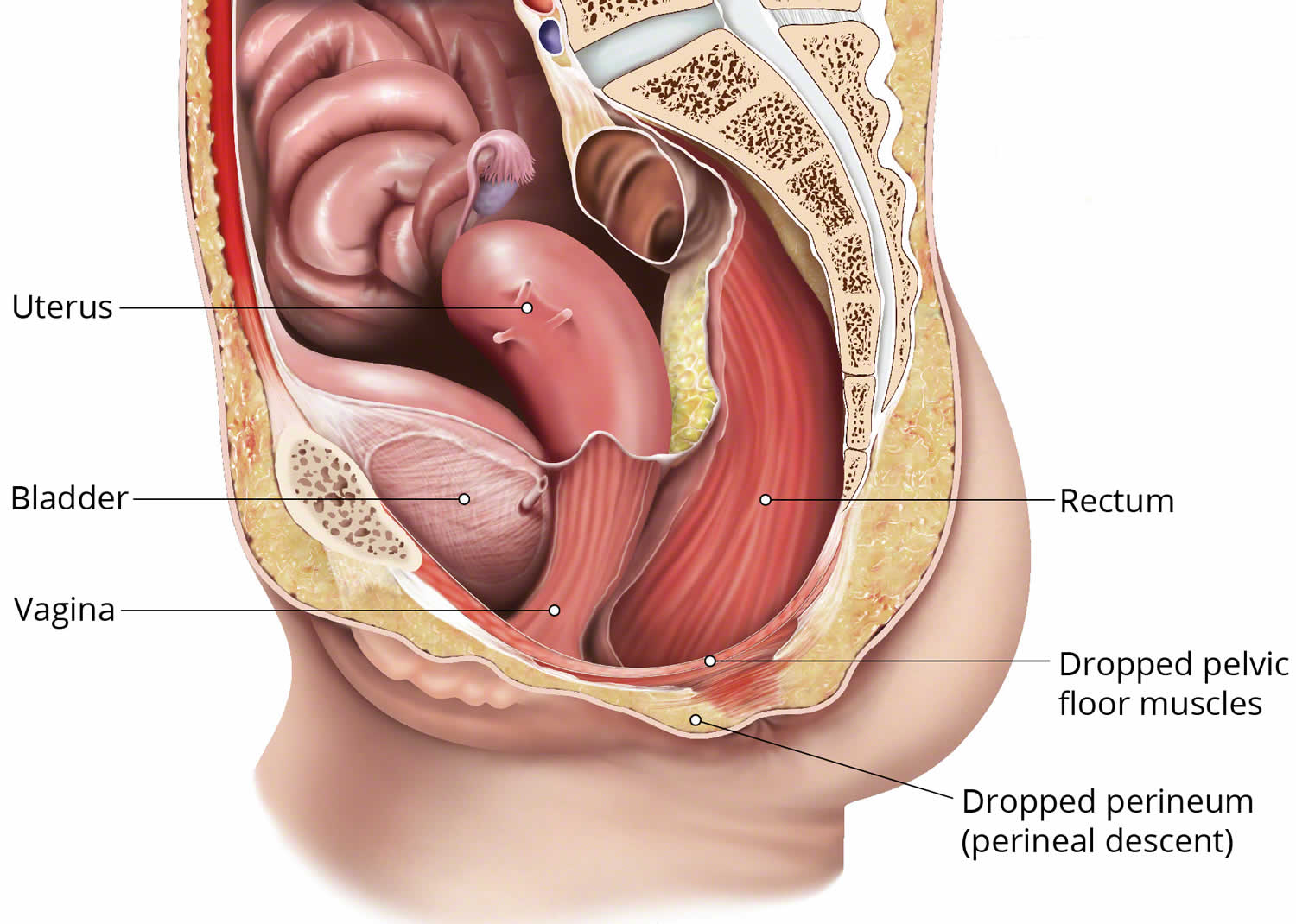

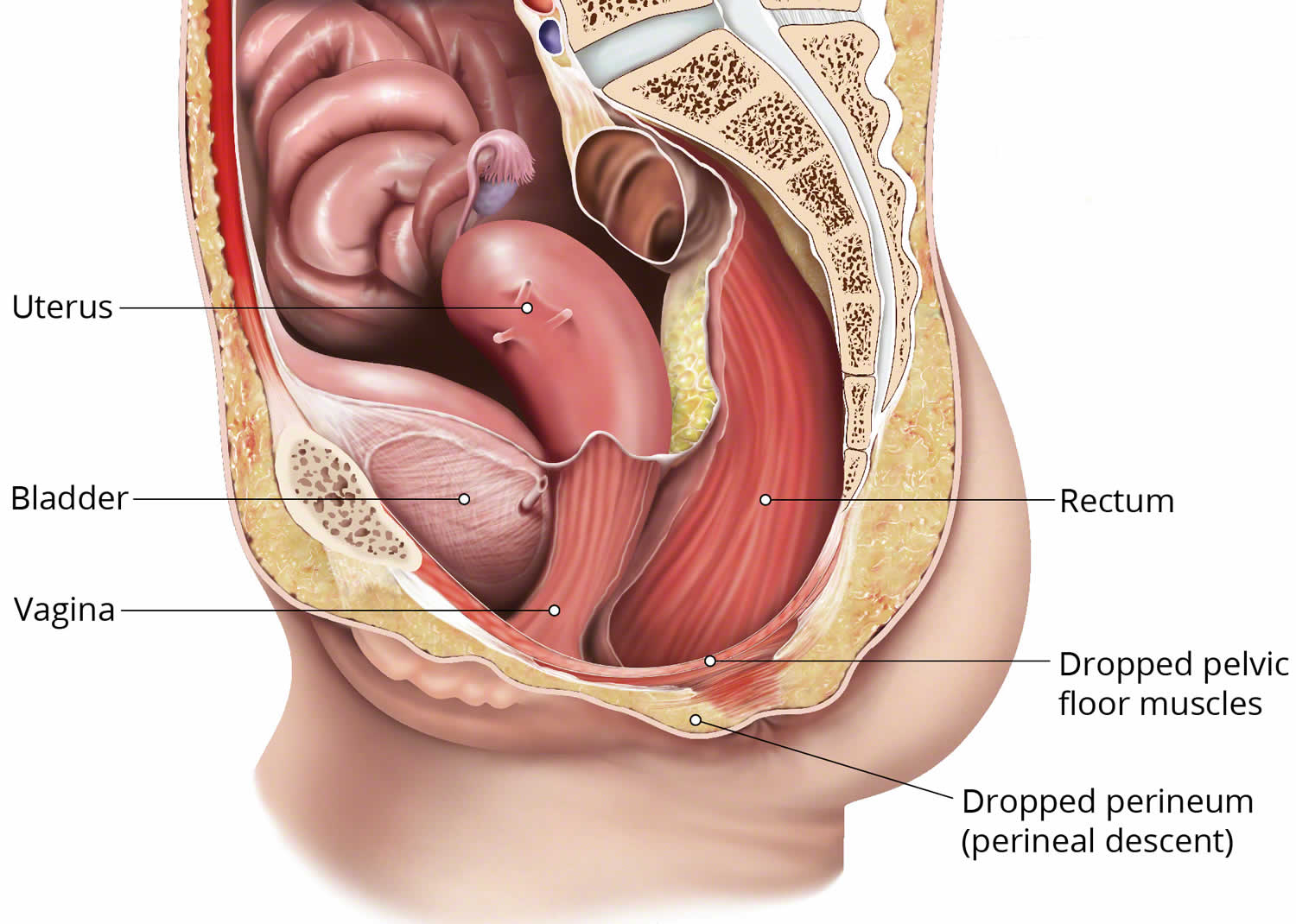

Figure 1. Descending perineum syndrome

Descending perineum syndrome causes

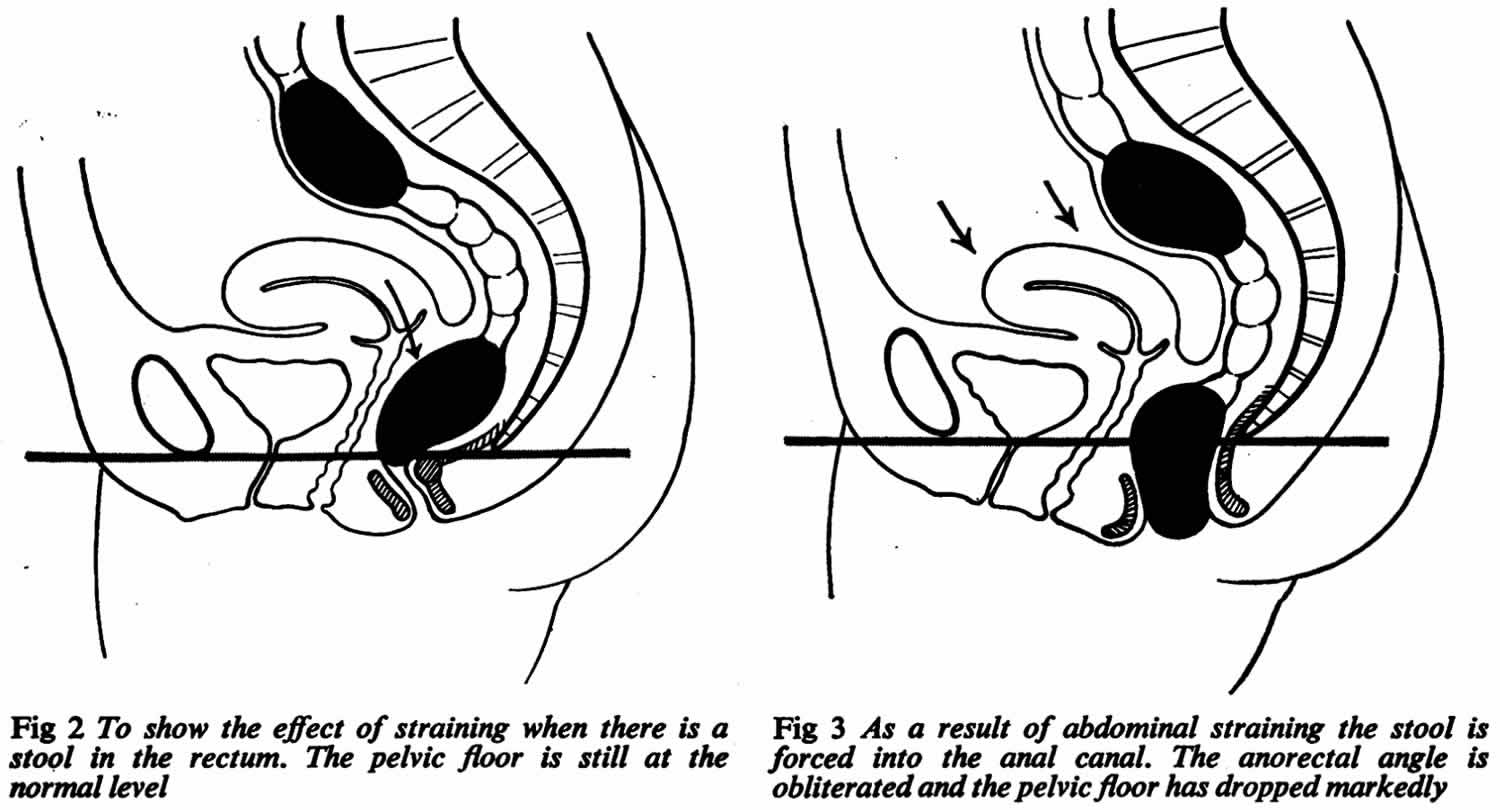

Several potential causes for descending perineum syndrome have been described. One of the main causes of descending perineum syndrome is thought to be excessive and repetitive straining. Straining forces the anterior rectal wall to protrude into the anal canal, this creates a sensation of incomplete defecation and weakness of the pelvic floor. This can happen if you suffer from chronic constipation; 90% of descending perineum cases are caused by chronic straining.

Other possible causes related to weak pelvic floor muscles is neuropathic degeneration of muscles that comes with old age or trauma to the pelvic floor muscles or the pudendal nerves supply during pregnancy and childbirth 7. 9% of descending perineum syndrome cases are caused by childbirth or labor. Pudendal neuropathy may also be the consequence of perineal descent syndrome. Descending perineum syndrome at its last stage is characterized by rectal prolapse and severe denervation 8 of the pudendal nerve consequent to up to 20% 8 overstretching with subsequent fecal incontinence as well as neuropathy 9.

Descending perineum syndrome prevention

The main method of preventing perineal descent is pelvic floor physical therapy. By strengthening the floor of the pelvis, symptoms of perineal descent syndrome can be reduced.

You can also avoid straining by improving fiber intake in your diet by eating foods such as wholegrains, fruit and vegetables.

Descending perineum syndrome symptoms

Descending perineum syndrome symptoms include:

- The need to press up on the perineum to help with bowel movements

- The feeling of the pelvis dropping during weighted activity

- Bowel and/or fecal incontinence

- Perineal descent is also often present in conjunction with pelvic organ prolapse.

Descending perineum syndrome diagnosis

Descending perineum syndrome is identifiable by clinical history and examination, and the most prevalent abnormality on testing is perineal descent > 4 cm; rectal balloon expulsion is an insensitive screening test for descending perineum syndrome 10.

Perineal descent syndrome can be measured with a perineocaliper although this device tends to underestimate the descent, particularly in obese patients 11.

Radiologically, perineal descent syndrome is defined as the descent of the anorectal junction below the pubococcygeal line extending from the inferior border of the pubic symphisis to the tip of the tailbone during straining 12. Initially, colpocystogram and defecography were used for imaging of perineal descent syndrome, but recently, dynamic MRI (DMRI) which provides visualization of the rectocele and movements of the pelvic floor has been demonstrated to be more accurate with less exposure to ionizing radiation 13. Dynamic MRI is a valuable adjunct test when a patient’s symptoms are more significant than the physical examination findings suggest. Its use for preoperative planning has made it more widespread 14.

Descending perineum syndrome treatment

The best treatment for descending perineum syndrome is yet to be defined 5. The first step in the treatment of descending perineum syndrome consists of preventing further damages by avoiding straining during defecation and emphasizing pelvic floor reeducation, pelvic floor exercises and biofeedback 15. Perineal descent syndrome is frequently associated with pelvic organ prolapse and it is reasonable to postulate, that treatment of pelvic organ prolapse will also have an impact on descending perineum syndrome.

Conservative medical management of descending perineum syndrome begins with behavioral modifications 16. A high fiber diet and increased water intake to reduce constipation/defecatory symptoms may be enough to improve the patient’s quality of life. The patient should be drinking at least 2 to 3 liters of nonalcoholic, noncaffeinated fluids daily. The patient can also begin performing Kegel exercises and may benefit from the supervision of a pelvic floor physiotherapist 17.

Harewood et al. 18 showed that efficacy of biofeedback seems to depend on the extent of perineal descent; patients who responded to pelvic floor exercises and biofeedback had a smaller perineal descent (mean 3.3 cm) than non-responders (mean 4.9 cm). Numerous studies demonstrated that the worse the perineal descent, the more difficult is efficacious treatment 18. They also found associated features between descending perineum syndrome and the female gender (96%), multiparity with vaginal delivery (55%) and with hysterectomy or vaginal cystocele and/or rectocele repair (74%) 18. Chang et al. 19 found a statistically significant association between descending perineum syndrome, age and increasing number of vaginal deliveries, whereas surgical history did not have any impact.

When the conservative treatment is unsuccessful, the next step is the use of a vaginal pessary. The vaginal pessaries come in different shapes and sizes. Therefore, fitting the patient with a pessary will come with a little trial and error. The function of this device is to stabilize the defects in the pelvic floor while also managing any other issues, such as cystoceles and prolapse of other organs 20. Pessaries have been used to manage pelvic organ prolapse since Hippocrates when he used a halved pomegranate to treat prolapse 21. Currently, there are a variety of devices used which differ in shape and size, made of medical-grade silicone. One of the most common shapes is the ring support pessary. Risk factors for pessary failure include large genital hiatus, short vaginal length, and prior pelvic organ prolapse surgery 21. If the pessary cannot be manually inserted, then it may be inserted under anesthesia, or it may not be a treatment option for the patient. The most common complications from pessary use include vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding, and odor 21. There is little evidence on how often a pessary cleaning and changing should be performed 22. However, teaching the patient how to remove and clean the pessary will increase the patient’s bodily autonomy 21.

For the most significant cases with rectal prolapse, Parks has developed a new surgical procedure called “post-anal perineorrhaphy” 23. This procedure, also known as “post-anal repair”, has been used by many other authors to treat fecal incontinence 24.

In 1982, Nichols 25 used a “retro-rectal levatorplasty” to treat an uncommon type of genital prolapse characterized by descent of the anus and sagging of the levator plate associated with severe constipation.

In 1987, Shafik 26 presented his experience with “levatorplasty” in the treatment of complete rectal prolapse.

Descending perineum syndrome surgery

Surgical management is reserved for those with obstructive defecatory symptoms and bothersome symptoms who have failed other forms of treatment 27. The method of surgical treatment will also depend on the prevalence of other conditions, such as rectocele, cystocele, or uterine prolapse, and their severity.

There are three main types of surgery used to correct descending perineum syndrome, these include:

- da Vinci sacrocolpoperineopexy – A surgeon uses a robotic platform to assist in surgery.

- Posterior vaginal mesh placement – Tissue that is weakened is brought together and supported with the use of transvaginal mesh.

- Perineorrhaphy – Perineal relaxation can occur when the opening to the vagina is stretched and relaxed; this can weaken the perineal muscles and decrease sensation. Perineorrhaphy is a procedure whereby the weakened perineal muscles are brought together for reinforcement.

Constipation and perineal descent may also be found along with rectal prolapse. If this is the case, rectopexy (rectal prolapse surgery) will be performed alongside sacrocolpoperineopexy.

References- Parks AG, Porter NH, Hardcastle J. The syndrome of the descending perineum. Proc R Soc Med. 1966;59(6):477-482. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1900931/pdf/procrsmed00182-0004.pdf

- Renzi A, Izzo D, Di Sarno G, Izzo G, Di Martino N. Stapled transanal rectal resection to treat obstructed defecation caused by rectal intussusception and rectocele. Int J Colorect Dis. (2006) 21:661–7. 10.1007/s00384-005-0066-5

- Chaudhry Z, Tarnay C. Descending perineum syndrome: a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and management. Int Urogynecol J. (2016) 27:1149–56. 10.1007/s00192-015-2889-0

- Villet R, Ayoub N, Salet-Lizee D, Bolner B, Kujas A. [Descending perineum in women]. Progr Urol. (2005) 15:265–71.

- Nessi A, Kane A, Vincens E, Salet-Lizée D, Lepigeon K, Villet R. Descending Perineum Associated With Pelvic Organ Prolapse Treated by Sacral Colpoperineopexy and Retrorectal Mesh Fixation: Preliminary Results. Front Surg. 2018;5:50. Published 2018 Sep 20. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2018.00050 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6159753

- Chaudhry, Z., Tarnay, C. Descending perineum syndrome: a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and management. Int Urogynecol J 27, 1149–1156 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-015-2889-0

- Ho YH, Goh HS. The neurophysiological significance of perineal descent. Int J Colorect Dis. (1995) 10:107–11.

- Henry MM, Parks AG, Swash M. The anal reflex in idiopathic faecal incontinence: an electrophysiological study. Br J Surg. (1980) 67:781–3.

- Pucciani F. Descending perineum syndrome: new perspectives. Techn Coloproctol. (2015) 19:443–8. 10.1007/s10151-015-1321-6

- Harewood GC, Coulie B, Camilleri M, Rath-Harvey D, Pemberton JH. Descending perineum syndrome: audit of clinical and laboratory features and outcome of pelvic floor retraining. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(1):126-130. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00782.x

- Broekhuis SR, Hendriks JC, Futterer JJ, Vierhout ME, Barentsz JO, Kluivers KB. Perineal descent and patients’ symptoms of anorectal dysfunction, pelvic organ prolapse, and urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. (2010) 21:721–9. 10.1007/s00192-010-1099-z

- Li M, Jiang T, Peng P, Yang XQ, Wang WC. Association of compartment defects in anorectal and pelvic floor dysfunction with female outlet obstruction constipation (OOC) by dynamic MR defecography. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2015) 19:1407–15.

- Patcharatrakul T, Rao SSC. Update on the Pathophysiology and Management of Anorectal Disorders. Gut Liver. 2018 Jul 15;12(4):375-384.

- Gupta AP, Pandya PR, Nguyen ML, Fashokun T, Macura KJ. Use of Dynamic MRI of the Pelvic Floor in the Assessment of Anterior Compartment Disorders. Curr Urol Rep. 2018 Nov 13;19(12):112.

- Beco J. Interest of retro-anal levator plate myorrhaphy in selected cases of descending perineum syndrome with positive anti-sagging test. BMC Surg. 2008;8:13. Published 2008 Jul 30. doi:10.1186/1471-2482-8-13 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2533292

- Ladd M, Tuma F. Rectocele. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546689

- Tso C, Lee W, Austin-Ketch T, Winkler H, Zitkus B. Nonsurgical Treatment Options for Women With Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Nurs Womens Health. 2018 Jun;22(3):228-239.

- Harewood GC, Coulie B, Camilleri M, Rath-Harvey D, Pemberton JH. Descending perineum syndrome: audit of clinical and laboratory features and outcome of pelvic floor retraining. Am J Gastroenterol. (1999) 94:126–30. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00782.x

- Chang J, Chung SS. An analysis of factors associated with increased perineal descent in women. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. (2012) 28:195–200. 10.3393/jksc.2012.28.4.195

- Bash KL. Review of vaginal pessaries. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2000 Jul;55(7):455-60.

- Lamers BH, Broekman BM, Milani AL. Pessary treatment for pelvic organ prolapse and health-related quality of life: a review. Int Urogynecol J. 2011 Jun;22(6):637-44.

- Hanson LA, Schulz JA, Flood CG, Cooley B, Tam F. Vaginal pessaries in managing women with pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence: patient characteristics and factors contributing to success. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006 Feb;17(2):155-9.

- Parks AG. Post-anal perineorrhaphy for rectal prolapse. Proc R Soc Med. 1967;60(9):920-921. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1902015/pdf/procrsmed00165-0116.pdf

- Matsuoka H, Mavrantonis C, Wexner SD, Oliveira L, Gilliland R, Pikarsky A. Postanal repair for fecal incontinence–is it worthwhile? Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1561–1567. doi: 10.1007/BF02236739

- Nichols DH. Retrorectal levatorplasty with colporrhaphy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1982;25:939–947. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198212000-00026

- Shafik A. A new concept of the anatomy of the anal sphincter mechanism and the physiology of defaecation. XXVIII – Complete rectal prolapse: a technique for repair. Coloproctology. 1987;9:345–352

- Hall GM, Shanmugan S, Nobel T, Paspulati R, Delaney CP, Reynolds HL, Stein SL, Champagne BJ. Symptomatic rectocele: what are the indications for repair? Am. J. Surg. 2014 Mar;207(3):375-9; discussion 378-9.