Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome

Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome are symptoms of antidepressant withdrawal that typically last for a few weeks 1. Antidepressant discontinuation symptoms occur with all classes of antidepressant. In fact, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labels for antidepressants caution about “dysphoric mood, irritability, agitation, dizziness, sensory disturbances (eg, paresthesias such as electric shock sensations and tinnitus), anxiety, confusion, headache, lethargy, emotional lability, insomnia, and hypomania” following discontinuation 2. However, certain antidepressants are more likely to cause antidepressant withdrawal syndrome symptoms than others. Discontinuation syndrome occurs with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), common symptoms including dizziness, headache, nausea and lethargy. Rare antidepressant discontinuation syndromes include extrapyramidal syndromes and mania/hypomania.

All these syndromes, even isolated discontinuation symptoms, share three common features that facilitate diagnosis:

- abrupt onset within days of stopping the antidepressant,

- a short duration when untreated and

- rapid resolution when the antidepressant is reinstated.

Quitting an antidepressant suddenly may cause symptoms within a day or two, such as:

- Anxiety

- Insomnia or vivid dreams

- Headaches

- Dizziness

- Tiredness

- Irritability

- Flu-like symptoms, including achy muscles and chills

- Nausea

- Electric shock sensations

- Return of depression symptoms

The minimum treatment duration required for the development of withdrawal phenomena has been insufficiently demonstrated; at least 4 weeks appear to be necessary 3. There is robust evidence for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) that there is a risk of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome from 8 weeks, and that this risk does not change to any relevant extent with longer treatment 4. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome appears to develop irrespective of the primary disorder 4.

Differentiating between antidepressant discontinuation syndrome and (re-)emergence of the primary psychiatric disorder is crucial. There is considerable symptom overlap between antidepressant discontinuation syndrome and a depressive episode or anxiety disorder, as well as a (hypo-)manic episode (Table 1 and 2). Misinterpretation of symptoms can result in unnecessary and potentially harmful medication (e.g., if antidepressant discontinuation syndrome is misinterpreted as a manic episode and subsequently misdiagnosed as a bipolar affective disorder). Likewise, when changing medication, antidepressant discontinuation syndrome due to the discontinued drug may be incorrectly identified as an adverse drug reaction to the new drug. A guiding criterion when making this differentiation can be the temporal course, which is characterized by early onset as well as fluctuations, and tends to be transient 5. The likeliest time course is onset in the first week following discontinuation and resolution in the second week 6. The fact that antidepressant discontinuation syndrome is generally more strongly and specifically defined by somatic symptoms, with symptoms untypical for depression such as dizziness, nausea, sensory impairment, and flu-like symptoms, can be used to help in the differentiation 7. Similarly, particular sleep disturbances such as vivid dreams and nightmares point to antidepressant discontinuation syndrome 5.

Clinicians need to be familiar with strategies for the prevention and management of such symptoms. Preventive strategies include warning patients about the possibility of discontinuation symptoms, encouraging good antidepressant adherence and tapering antidepressants at the end of treatment. Most symptoms are mild and short-lived. Consequently symptoms that follow planned termination of an antidepressant can often be managed by providing an explanation and reassurance. More severe symptoms should be treated symptomatically or the antidepressant restarted, in which case symptoms usually resolve within 24 hours. More cautious tapering can then follow.

Having antidepressant withdrawal symptoms doesn’t mean you’re addicted to an antidepressant. Addiction represents harmful, long-term chemical changes in the brain. It’s characterized by intense cravings, the inability to control your use of a substance and negative consequences from that substance use. Antidepressants don’t cause these issues.

To minimize the risk of antidepressant withdrawal, talk with your doctor before you stop taking an antidepressant. Your doctor may recommend that you gradually reduce the dose of your antidepressant for several weeks or more to allow your body to adapt to the absence of the medication.

In some cases, your doctor may prescribe another antidepressant or another type of medication on a short-term basis to help ease symptoms as your body adjusts. If you’re switching from one type of antidepressant to another, your doctor may have you start taking the new one before you completely stop taking the original medication.

It’s sometimes difficult to tell the difference between withdrawal symptoms and returning depression symptoms after you stop taking an antidepressant. Keep your doctor informed of your signs and symptoms. If your depression symptoms return, your doctor may recommend that you start taking an antidepressant again or that you get other treatment.

An accurate differential diagnosis is important, since it has crucial clinical consequences. For example, in the case of transient withdrawal phenomena, one can usually take a wait-and-see approach or treat symptomatically. In the case of disease recurrence, on the other hand, medication may need to be resumed. If pharmaceutical drugs are actually known to be associated with a risk of rebound following discontinuation, this needs to be taken into account as early on as at the time of making the indication and providing patient information.

Table 1. Differential diagnosis following antidepressant discontinuation or dose reduction

| Syndrome | Characteristic |

| Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome, acute discontinuation syndrome, withdrawal syndrome, | ● Rapid onset following discontinuation |

| ● Transient, self-limiting | |

| ● Rapid improvement following resumption of the medication | |

| ● Symptoms may resemble (or differ from) primary disorder (depression) | |

| ● Typically nonspecific symptoms (“FINISH,” see text), possibly specific serotonergic/ cholinergic syndromes | |

| Rebound | ● Re-emergence of symptoms of the primary disorder to a greater extent than prior to medication and/or |

| ● Higher risk for relapse compared to patients not receiving antidepressants | |

| ● Counter-regulatory mechanisms activated by treatment and excessive counter-regulation following drug discontinuations | |

| Relapse | Re-emergence of the same disease episode due to loss of pharmacological effect |

| Recurrence | New episode of a recurring primary disorder following previous recovery (remission over 6–9 months) due to loss of pharmacological effect |

Table 2. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome risk for individual drugs

| Risk of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome | Antidepressant |

| Very high risk | Tranylcypromine, phenelzine |

| High risk | Paroxetine, tricyclic antidepressants, venlafaxine (desvenlafaxine) |

| Moderate risk | Citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, duloxetine, vortioxetine |

| Low risk | Fluoxetine, milnacipran |

| No risk | Agomelatine |

| Unclear risk (insufficient evidence) | Mirtazapine, bupropion |

Discontinuation syndrome key points

- Discontinuation syndrome symptoms include flu-like symptoms, insomnia, nausea, imbalance, sensory disturbances and hyperarousal. You can use the mnemonic FINISH to keep these symptoms in mind.

- F for flu-like symptoms,

- I for Insomnia,

- N for nausea,

- I for imbalance,

- S for sensory disturbances, and

- H for hyperarousal.

- Discontinuation syndrome is more commonly seen with paroxetine.

- From a therapeutic standpoint, restarting the antidepressant is generally enough as management strategy.

How do I differentiate discontinuation symptoms from a depressive relapse?

They have in common symptoms such as dysphoria, appetite changes, sleep problems and fatigue. It’s practical to look for symptoms that are not seen in depression relapse, some examples are dizziness, “electric shock” sensations, rushing sensations in the head, headache and nausea. Also, you can see a rapid reversal of symptoms after restarting the antidepressant.

Do antidepressants cause addiction?

There has long been a debate on whether the withdrawal symptoms caused by antidepressant discontinuation indicate addiction 9. According to International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) 10, dependence on a substance, whether drugs, alcohol, or medications, is present if at least three of six criteria are met: tolerance development, withdrawal symptoms, strong desire to use the substance, difficulty controlling its use, neglecting other interests, and persistent substance use despite harmful effects. Withdrawal symptoms and tolerance development are considered to be the effect of counter-regulatory neuroadaptation opposing the effects of the substance in order to preserve homeostasis 11. On the one hand, this can lead to the loss of the original drug effect. Reports have described that, following discontinuation, reinstatement of an antidepressant is no longer able to achieve the original effect, which can be interpreted as tolerance development 12. On the other hand, abrupt discontinuation of the substance causes withdrawal symptoms, since the newly established balance is disrupted by discontinuing substance use. Withdrawal symptoms are thus not a manifestation of a desire for the discontinued substance; they are much more the effect of previous adaption, as is the case of many centrally or peripherally active medications, e.g., ß-blockers or acetylsalicylic acid 13. Therefore, tolerance development and withdrawal symptoms are not specific to drug effects and are not sufficient, even in the case of a protracted course 9 to diagnose an addiction disorder.

Unlike addiction-forming drugs, antidepressants do not cause an uncontrolled desire to use the substance or a loss of control, and also do not confine behavior or interests to antidepressant use 11. Persistent substance use despite harmful effects has not been described. Only for the monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) tranylcypromine have isolated cases of unauthorized dose increases been described 14, which may be due to the special pharmacological effect on dopaminergic neurotransmission 15.

So who is at risk of discontinuing medication without letting their doctor know?

Generally, patients who begin to feel better and are not comfortable with the idea of taking medication for a long time. Also, women who discover they are pregnant are more likely to abruptly stop medications, because of safety concerns.

So, what do you do with a patient suffering from discontinuation symptoms?

First of all, you provide reassurance. Doctors do this by explaining that antidepressant discontinuation syndrome is reversible, not life-threatening, and that it will run its course within 1 to 2 weeks.

Second, dcotors restart the medication with a slow dose taper.

What if symptoms occur during tapering?

In this case, your doctor should consider restarting at the original dose and then taper at a slower rate. If slow tapering is poorly tolerated, your doctor can consider substituting with fluoxetine.

Discontinuation syndrome causes

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

A sufficiently large number of methodologically high-quality studies are available on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI; evidence level I and II according to Table 3). With its especially long half-life, fluoxetine is particularly unproblematic, even in the case of abrupt discontinuation 16. Sertraline and in particular citalopram and escitalopram pose low risk. Studies revealed no significant benefit for tapered withdrawal compared to continuing the medication 17, while abrupt discontinuation carries low risk (approximately 20% compared to 10% in the continuation arms) 6.

Paroxetine is associated with a high risk for antidepressant discontinuation syndrome compared to other SSRI and, in the case of abrupt discontinuation, antidepressant discontinuation syndrome symptoms are seen in over 30% of patients 18. With the exception of paroxetine, which causes antidepressant discontinuation syndrome symptoms more closely resembling those seen with tricyclic antidepressants in terms of frequency and severity 19, SSRI-related antidepressant discontinuation syndrome is generally mild and self-limiting.

Table 3. Methodological quality in terms of the diagnostic question (frequency, severity, and characteristics of discontinuation phenomena with antidepressants)

| Level of methodological quality/evidence level | Specific features | Strengths/limitations |

| I | Discontinuation under placebo substitution compared to continuation of medication, randomized, blinded | Lowest risk of bias, including assessment of absolute frequencies of occurrence |

| II | Discontinuation of one drug compared to discontinuation of another drug | Comparison of various drugs with each other for the risk of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome, no assessment of absolute incidence as there is no continuation arm |

| III | Discontinuation under placebo substitution (blinded for patients), no control group | Lack of control, but lower risk of bias due to patient blinding |

| IVa | Cohort studies, case series, unblinded | High risk of bias |

| IVb | Individual case reports | Highest risk of bias, no causal relationships can be assessed |

Selective serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors

There is robust evidence (level I and II) on selective serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRI). Venlafaxine (and desvenlafaxine) carry a higher risk for antidepressant discontinuation syndrome 20 compared to both the SNRI duloxetine 21 and SSRI (escitalopram, sertraline) 22. Venlaflaxine also appears to more frequently cause severe forms of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome 23. Moreover, this appears to be the case with particularly early onset withdrawal symptoms (according to some case reports, as early on as after a delayed dose), which can be linked to the drug’s extremely short half-life. Duloxetine carries a low risk for antidepressant discontinuation syndrome 21 in comparison; this, however, rises in the high-dose range (120 mg/day) 24. The third SNRI, milnacripran, showed no antidepressant discontinuation syndrome symptoms in a methodologically high-quality study (level I, in the psychosomatic indication “fibromyalgia”) even upon abrupt discontinuation 25. Similarly, an open study revealed only isolated occurrences of anxiety 26.

Tricyclic antidepressants

The evidence on tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) is limited, and there are only a handful of methodologically high-quality studies (level I and II), some with very low case numbers. However, these point to a high risk for antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. Even when amitriptyline was tapered out gradually, 80% of patients exhibited symptoms (N = 15), albeit primarily mild and self-limiting 27. Imipramine was comparable to the SSRI paroxetine 19. Methodologically weak studies and case series (level III and IV) yield evidence that there is a risk for severe effects following discontinuation of TCA 28. Symptoms related to cholinergic overdrive are clinically characteristic 29.

MAO inhibitors

There are only case reports and two studies of low methodological quality on MAO inhibitors (MAOI) 30. Taking these methodological limitations into account, MAOI appear to be associated with a particularly high risk for antidepressant discontinuation syndrome; severe courses appear to be more common. Delirium was described in 50% of case reports on antidepressant discontinuation syndrome following discontinuation of tranylcypromine 30.

Agomelatine

A number of methodologically high-quality studies (level I) demonstrate that antidepressant discontinuation syndrome does not occur even following abrupt discontinuation of agomelatine 31.

Mirtazapine and bupropion

Although studies are lacking, a handful of case reports suggest that discontinuation of mirtazapine and bupropion can also cause antidepressant discontinuation syndrome 32.

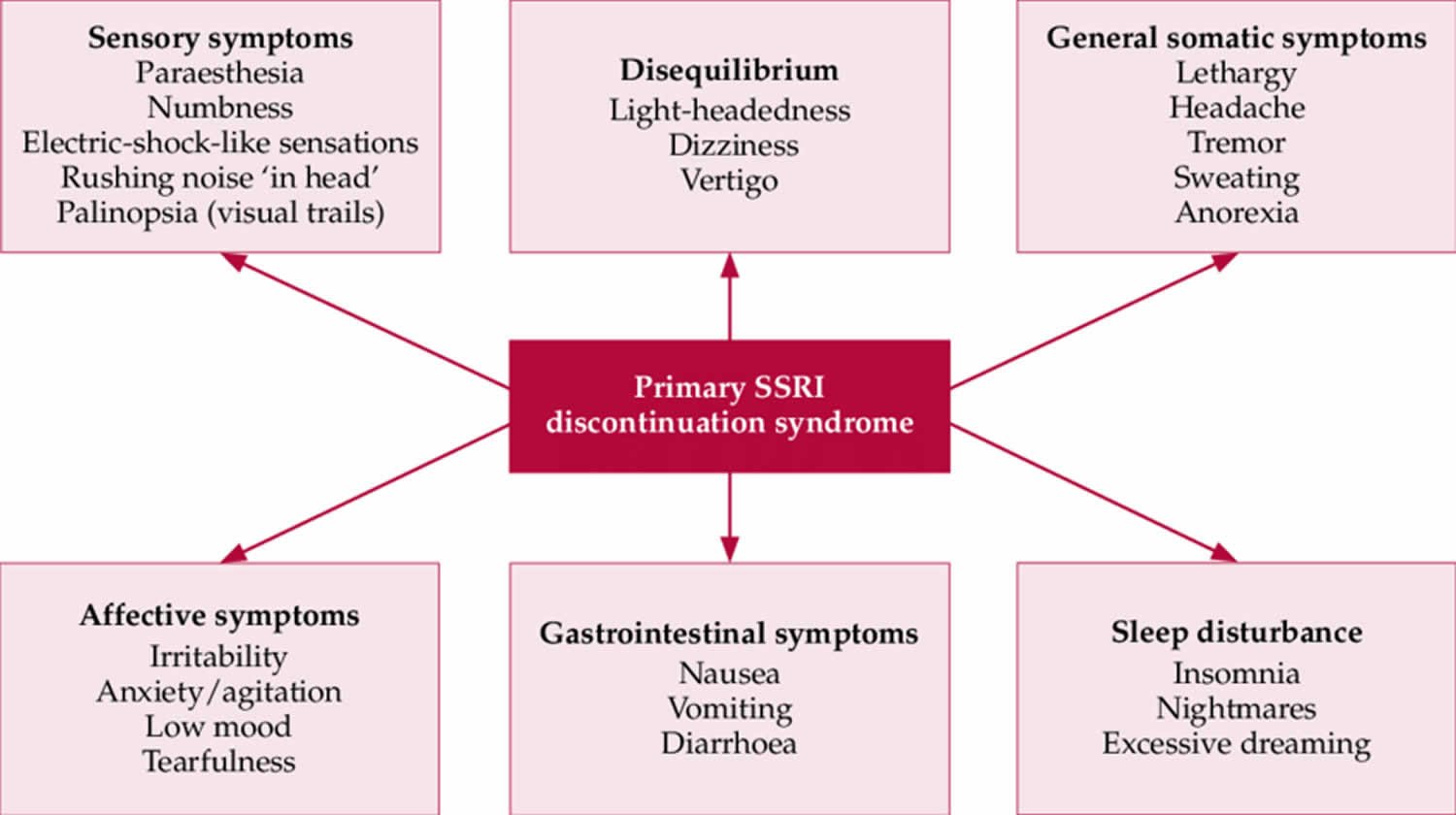

Discontinuation syndrome symptoms

The symptoms described below are commonly associated with the discontinuation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) 33. Specific symptoms for tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) have been described 34. In the case of tricyclic antidepressants, there is a lack of sensory abnormalities and problems with equilibrium 35. In the case of MAOIs, symptoms can be more severe, including a worsening of depressive episode, acute confusional state, anxiety symptoms and even catatonia 36.

Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome was initially based on case reports, but the evidence expanded to include prospective studies, with randomized double-blind interruption periods.

The discontinuation syndrome of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) can be divided into six clusters of symptoms.

- Sensory symptoms. Sensory symptoms include paresthesia, numbness, electric shock-like sensations, rushing noise “ in head” and palinopsia, or visual trails.

- Disequilibrium symptoms. Disequilibrium symptoms include light-headedness, dizziness and vertigo.

- General somatic symptoms. General somatic symptoms have been compared to a flu-like syndrome. This includes lethargy, headache, tremor, sweating and anorexia.

- Affective symptoms. Affective symptoms that can be part of the discontinuation syndrome are irritability, anxiety, low mood and tearfulness.

- Gastrointestinal symptoms. Gastrointestinal symptoms include nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

- Sleep disturbance. Sleep disturbances include insomnia, nightmares and excessive dreaming.

There’s also a mnemonic to help us remember the discontinuation symptoms.

It’s the word FINISH 37:

- F for flu-like symptoms,

- I for Insomnia (disturbed sleep, vivid dreams/nightmares),

- N for nausea,

- I for imbalance (vertigo, light-headedness),

- S for sensory disturbances (electric shock-like sensations, dysesthesia),

- H for hyperarousal (anxiety, agitation, irritability, etc.).

Characteristics of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. Different specific features are seen depending on the drug.

Characteristics of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome 8:

- Rapid onset mostly within 1 week following discontinuation (generally peaking after 36–96 h), after approximately 3–5 half-lives

- Spontaneous resolution within 2 (–6) weeks (depending on half-life)

- Predominantly mild, reversible symptoms

- Rapid and generally complete resolution if medication is resumed

- Nonspecific physical symptoms typically predominate

- Commonest symptoms: dizziness, nausea, headache, disturbed sleep, irritability/emotional lability

Table 4. Clinical presentations of antidepressant withdrawal symptoms

| Systemic, cardiac | Flu-like symptoms*2, dizziness/drowsiness*2, tachycardia*2, impaired balance, fatigue, weakness, headache, dyspnea |

| Sensory | Parasthesia*2, electric shock–like sensation (“brain zapps/body zapps”)*2, sensory disorders, dysesthesia, itch, tinnitus, altered taste, blurred vision, visual changes |

| Neuromuscular | Muscle tension*2, myalgia*2, neuralgia*2, agitation*2, ataxia*2, tremor |

| Vasomotor | Perspiration*2, flushing*2, chills*2, impaired temperature regulation |

| Gastrointestinal | Diarrhea*2, abdominal pain*2, anorexia, nausea, vomiting |

| Sexual | Premature ejaculation*2, genital hypersensitivity*2 |

| Sleep | Insomnia, nightmares, vivid dreams, hypersomnia |

| Cognitive | Confusion*2, disorientation*2, amnesia*2, reduced concentration |

| Affective | Irritability, anxiety, agitation, tension, panic, depressive mood, impulsivity, sudden crying, outbursts of anger, mania, increased drive, mood swings, increased suicidal thoughts, derealization, depersonalization |

| Psychotic | Visual and auditory hallucinations |

| Delirium | (Typically only with tranylcypromine) |

Footnotes: Symptoms shown in bold occur frequently

*1 Adapted from: Fava 2015 38 and Chouinard 2015 39

*2 Specifically serotonin-related

[Source 8 ]Table 5. Signs and symptoms of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome

| SSRI | Atypical antidepressant | Tricyclic antidepressant | MAOI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | ||||

| Flu-like symptoms | + | + | + | – |

| Headache | + | + | + | + |

| Lethargy | + | + | + | – |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||

| Abdominal cramping | + | – | + | – |

| Abdominal pain | + | – | + | – |

| Appetite disturbance | + | + | + | – |

| Diarrhea | + | + | – | |

| Nausea/vomiting | + | + | + | – |

| Sleep | ||||

| Insomnia | + | + | + | + |

| Nightmares | + | + | + | + |

| Balance | ||||

| Ataxia | + | – | + | – |

| Dizziness | + | + | + | – |

| Lightheadedness | + | – | + | – |

| Vertigo | + | + | + | – |

| Sensory | ||||

| Blurred vision | + | – | – | – |

| “Electric shock” sensations | + | + | – | – |

| Numbness | + | – | – | – |

| Paresthesia | + | + | – | – |

| Movement | ||||

| Akathisia | + | + | + | – |

| Myoclonic jerks | – | – | – | + |

| Parkinsonism | + | – | + | – |

| Tremor | + | – | + | – |

| Affective | ||||

| Aggression/irritability | + | – | – | + |

| Agitation | + | – | + | + |

| Anxiety | + | + | + | – |

| Low mood | + | + | + | + |

| Psychosis | ||||

| Catatonia | – | – | – | + |

| Delirium | – | – | – | + |

| Delusions | – | – | – | + |

| Hallucinations | – | – | – | + |

Footnote: Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome symptom categories are listed by rate of incidence.

Abbreviations: SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor: + = occur in withdrawal from this medication; – = do not occur in withdrawal from this medication.

[Source 40 ]Time of onset and duration

Discontinuation symptoms occur generally during the first week after stopping the antidepressant. Studies suggest a mean time of onset of 2 days after stopping. Regarding duration, spontaneous resolution occurs between 1 day and 3 weeks after onset, most commonly around 10 days.

The discontinuation syndrome has been reported in relation to almost every SSRI, although there are increased reports in patients stopping paroxetine treatment. So far, the half-life is the pharmacokinetic property that has been linked to risk of discontinuation symptoms. Fluoxetine has a half-life of around 7 days, this makes it the SSRI with the lowest risk of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome.

Severe cases of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome

Uncontrolled studies and (online) surveys suggest higher incidence rates of antidepressant withdrawal effects in general, as well as more severe symptoms 41. However, one needs to take into consideration the methodological limitations and the danger of incorrectly attributing causality to associations. For example, blinded randomized controlled trials revealed equally high rates of withdrawal symptoms in the control arms (>30%), i.e., in which the antidepressant was continued 20. Controlled, high-quality studies point to a primarily self-limiting course involving mild symptoms. In rare cases, symptoms that were classified as more severe were seen. These were mainly sleep disorders and nervousness/anxiety (desvenlafaxine) 42. Severe courses involving extrapyramidal motor symptoms (such as parkinsonism and akathisia) or paradoxical activation/mania are known from methodologically weaker studies and case reports. These were described following discontinuation of tricyclic antidepressants 43, MAO inhibitors 30, SSRI 44, venlafaxine 45, and mirtazapine 46 in patients with uni- and bipolar disorders, as well as symptoms that are of particular clinical relevance such as suicidal thoughts 47. The sensation of electric shocks experienced by patients as particularly impairing (especially with SSRI and venlafaxine) is a specific aspect worthy of note 48.

Rebound phenomena

Rebound phenomena refer to the organism’s increased susceptibility following drug discontinuation—comparable to the image of a ball which, when pushed under water and suddenly released, not only returns to the surface, but actually rises out of the water: the symptoms of the underlying disease return to a greater extent than prior to drug initiation, or there is a greater risk of relapse compared to patients that did not receive medication.

Individual case reports and case series report persistent depressive syndrome following antidepressant discontinuation—more severe in nature compared to before starting medication or with additional psychopathological symptoms, some of which are challenging to treat 39. Some authors define these as persistent post-discontinuation syndromes if symptoms persist for longer than 6 weeks 49. Anxiety and panic disorders, sleep disorders, and cyclothymic/bipolar disorders have been reported following discontinuation of paroxetine, escitalopram, citalopram, and fluvoxamine, whereby paroxetine appears to harbor a particularly high risk 39. The available evidence does not permit any statements to be made on the frequency of rebound phenomena. There is only one open and uncontrolled study in this regard, which describes persistent mood swings following discontinuation of paroxetine in three of 20 patients 50.

A literature search does not systematically answer the question of whether an increased risk of recurrence following discontinuation can be demonstrated. However, a 2011 meta-analysis 51 showed that depressive patients who experienced remission with antidepressants relapsed more frequently following discontinuation (42.0%–55.6%) than did those that experienced remission with placebo (24.7%). The risk was higher for antidepressants that alter monoaminergic neurotransmission more strongly, i.e,. in particular MAOI and TCA. The risk of relapse is particularly high in the first 6 months following discontinuation 52. Evidence suggests that the risk of relapse is higher the longer the drug was previously taken 53. However, the reliability of this evidence from secondary analyses is limited due to study design (e.g., separate observation of study arms). Given its considerable clinical relevance, the topic urgently requires further research.

How to discontinue antidepressants

First, patient education is very important. Warn patients about the possibility of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. The FDA prescribing label recommends gradual reduction in dose instead of abrupt discontinuation. Guidelines recommend short tapers, of between 2 weeks and 4 weeks, down to therapeutic minimum doses, or half-minimum doses, before complete cessation 54. Studies have shown that these tapers show minimal benefits over abrupt discontinuation, and are often not tolerated by patients. Tapers over a period of months and down to doses much lower than minimum therapeutic doses have shown greater success in reducing withdrawal symptoms. Other types of medication associated with withdrawal, such as benzodiazepenes, are tapered to reduce their biological effect at receptors by fixed amounts to minimise withdrawal symptoms. These dose reductions are done with exponential tapering programmes that reach very small doses. This method could have relevance for tapering of SSRIs.

In their excellent manuscript, published in The Lancet Psychiatry, Mark Horowitz and David Taylor 55 share their personal view on tapering of SSRI treatment to mitigate antidepressant withdrawal symptoms. In the Netherlands, this topic has been raising debate as well 56, which urged representatives of the Dutch college of General Practitioners, the Royal Dutch Pharmacists Association, the Dutch Association for Psychiatry, and the patient organization MIND to develop multidisciplinary recommendations for the discontinuation of SSRIs and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Independent of Horowitz and Taylor 57, but with identical reasoning, we proposed reducing doses of SSRIs or SNRIs hyperbolically, and Ruhe et al 58 also advocated the strategy of mini-tapering.

Table 6. Steps in dosing to discontinue SSRIs and SNRIs in case of one or more risk factors for acute withdrawal syndrome

| Citalopram (mg/day) | Escitalopram (mg/day) | Fluvoxamine (mg/day) | Paroxetine (mg/day) | Sertraline (mg/day) | Duloxetine (mg/day) | Venlafaxine (mg/day) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 20·0 | 10·00 | 50·0 | 20·0 | 50·00 | 60·0 | 75·0 |

| Step 2 | 10·0 | 5·00 | 30·0 | 10·0 | 25·00 | 30·0 | 37·5 |

| Step 3 | 6·0 | 3·00 | 20·0 | 7·0 | 15·00 | 15·0 | 20·0 |

| Step 4 | 4·0 | 2·00 | 15·0 | 5·0 | 10·00 | 10·0 | 12·0 |

| Step 5 | 3·0 | 1·50 | 10·0 | 3·0 | 7·50 | 6·0 | 7·0 |

| Step 6 | 2·0 | 1·00 | 5·0 | 2·0 | 5·00 | 4·0 | 5·0 |

| Step 7 | 1·0 | 0·50 | 2·5 | 1·0 | 2·50 | 2·0 | 3·0 |

| Step 8 | 0·5 | 0·25 | 0·0 | 0·5 | 1·25 | 1·0 | 2·0 |

| Step 9 | 0·0 | 0·00 | .. | 0·0 | 0·00 | 0·0 | 1·0 |

| Step 10 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 0·0 |

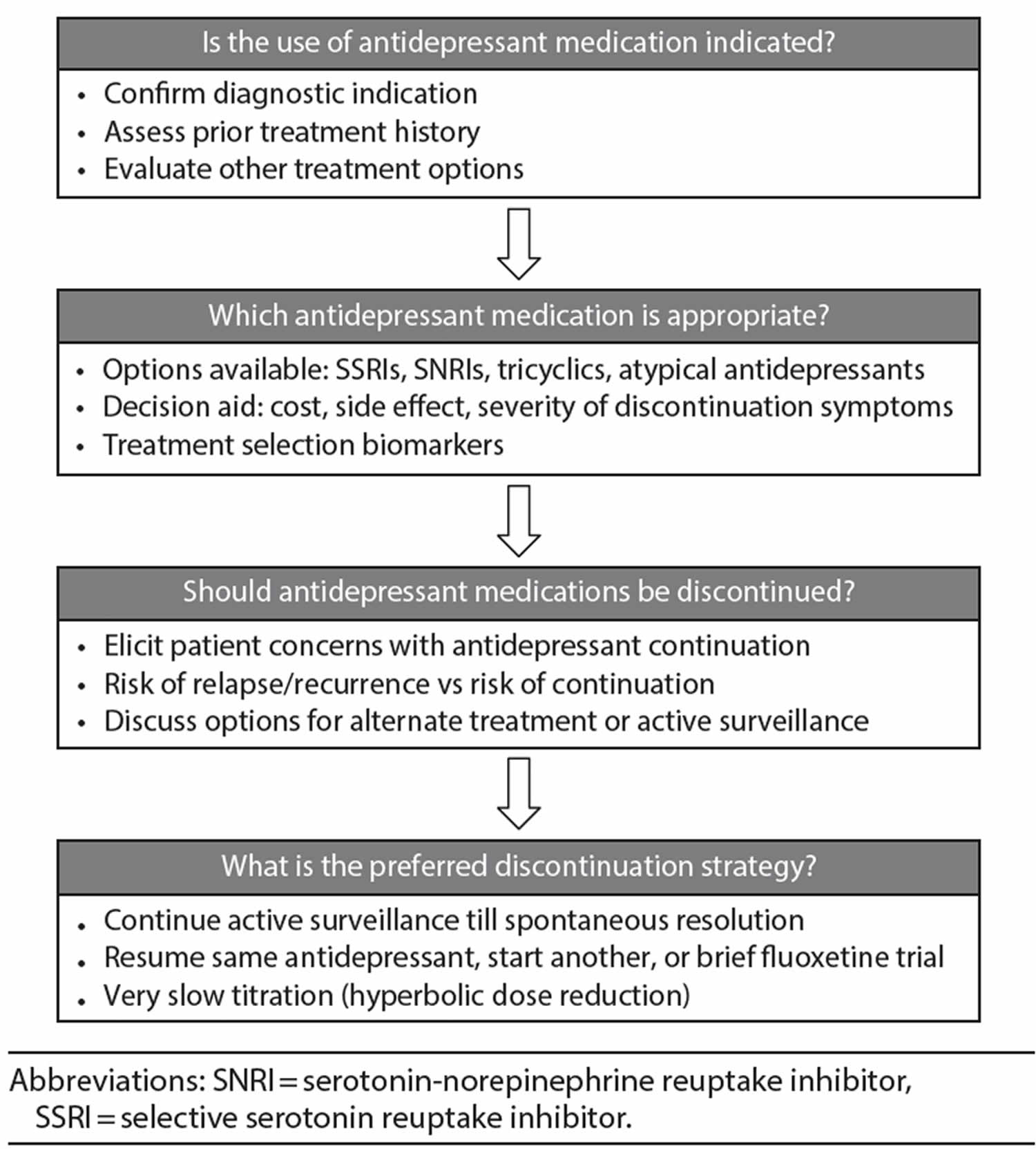

As noted by Fava et al 59, gradual taper has not been shown to help in reducing the frequency of discontinuation syndrome. However, gradual taper has been shown to reduce the likelihood of symptomatic relapse over the next year after discontinuation 60. This discrepancy might be attributed to the short periods of taper used in previous studies. Thus, Horowitz and Taylor 55 recently proposed hyperbolic dose reduction, which was extended by Ruhe et al 58 as a multistep

dose reduction paradigm in which the initial step is to reduce the dose to half of the minimally effective dose in 1 week and then reduce very gradually and decide the time spent at each dose by shared decision-making between clinician and the patient. If symptoms are tolerable and not burdensome, active surveillance using the measurement-based care approach until spontaneous resolution may be an option. If the symptoms are intolerable, management strategies may include resumption of previously tolerated dose, switch to adequate dose of another SSRI/SNRI, cross-tapering—reducing the dose of current medication gradually while increasing the dose of another or using a brief trial of fluoxetine to bridge from an SSRI/SNRI to a nonserotonergic antidepressant like bupropion 61. Clinicians should elicit the patient’s views about discontinuation and iteratively find the optimal strategy for individual patients.

Using the Shared Decision-Making approach, clinicians and patients (along with other health professionals, friends, and family) make an optimal treatment decision when an unequivocally superior option does not exist 62. This process is bidirectional: the clinician shares information about available options, including the risks and benefits, while the patient conveys his or her specific preferences or values 62. In clinical practice, Shared Decision-Making can be implemented by a simple 3-step model that offers choices, discusses options, and moves patients toward making a decision 63. Decision aids are important tools of Shared Decision-Making as they facilitate sharing of knowledge and can be used outside of a clinic visit. A decision aid tool developed specifically for antidepressants was shown to improve the comfort of making decisions in both patients and clinicians 64.

Figure 1. Decisional uncertainties that patients and clinicians face regarding the use and discontinuation of antidepressants

Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome treatment and prevention

The most important treatment approach likely lies in prevention. Since symptoms are mild and self-limiting in the majority of cases, detailed patient education is often sufficient; if necessary, patients can receive symptomatic treatment in the form of hypnotic agents or anti-muscarinic substances for TCA and cholinergic rebound 65. In the case of severe symptoms, the antidepressant can be resumed, which generally leads to complete symptom remission within 24 hours 66. This also applies to extrapyramidal symptoms and paradoxical activation/mania. A gradual tapering can then be undertaken. Although antidepressant tapering is not able to completely rule out the risk of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome, it appears to reduce its severity 20. A time period of 2 weeks is too short 20—the German clinical practice guidelines recommend reducing a drug over a period of at least 4 weeks 67. Findings from narcolepsy research even suggest minimum periods of 3 months 68. Treating physicians should make decisions depending on the particular drug and taper over longer periods in the case of high initial doses and high-risk drugs (see Table 2 above). Fluoxetine has proven itself in case reports as a “rescue” substance for withdrawal symptoms from other SSRI 69 and venlafaxine 70. It can be used instead of the discontinued drug if antidepressant discontinuation syndrome does emerge and then presumably abruptly discontinued after a number of weeks.

Risk of rebound

Signs of rebound phenomena following discontinuation are to be taken seriously; however, these are often challenging to clinically differentiate from a re-emergence of the primary disorder, since this, too, can change in terms of symptoms and severity over its natural course. Depressive syndromes, for example, are often combined with anxiety disorders, and manic episodes of bipolar disorders often emerge in a delayed manner following what originally appeared to be unipolar depression 71.

The concern that, once started, an antidepressant can no longer be discontinued due to the risk of sudden, severe, and in some cases treatment-resistant recurrence 72 should prompt caution when starting an antidepressant, all the more so in the case of moderate depression, particularly since antidepressants are scarcely superior to placebo here 73.

References- Discontinuing Antidepressants: How Can Clinicians Guide Patients and Drive Research? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 26 Nov 2019, 80(6) DOI: 10.4088/jcp.19com13047 http://www.psychiatrist.com/JCP/article/_layouts/ppp.psych.controls/BinaryViewer.ashx?Article=/JCP/article/Pages/2019/v80/19com13047.aspx&Type=Article

- Paroxetine [package insert]. Research Triangle, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2012.

- Hohagen F, Montero RF, Weiss E, et al. Treatment of primary insomnia with trimipramine: an alternative to benzodiazepine hypnotics? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;244:65–72.

- Baldwin DS, Montgomery SA, Nil R, Lader M. Discontinuation symptoms in depression and anxiety disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;10:73–84.

- Harvey BH, Slabbert FN. New insights on the antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2014;29:503–516.

- Montgomery SA, Nil R, Dürr-Pal N, Loft H, Boulenger JP. A 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of escitalopram for the prevention of generalized social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1270–1278.

- Michelson D, Amsterdam J, Apter J, et al. Hormonal markers of stress response following interruption of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25:169–177

- Henssler J, Heinz A, Brandt L, Bschor T. Antidepressant Withdrawal and Rebound Phenomena. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116(20):355–361. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2019.0355 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6637660

- Voderholzer U. Machen Antidepressiva abhängig? Pro Psychiatr Prax. 2018;45:344–345.

- WHO. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related health problems, 10th revision, 5th edition. World Health Organization. 2015

- Heinz A, Daedelow L, Wackerhagen C, Di Chiara G. Addiction theory matters—why there is no dependence on caffeine or antidepressant medication. Addict Biol. 2019

- Bosman RC, Waumans RC, Jacobs GE, et al. Failure to respond after reinstatement of antidepressant medication: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2018;87:268–275.

- Reidenberg MM. Drug discontinuation effects are part of the pharmacology of a drug. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339:324–328.

- Westermeyer J. Addiction to tranylcypromine (Parnate): a case report. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1989;15:345–350.

- Heinz AJ, Beck A, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Sterzer P, Heinz A. Cognitive and neurobiological mechanisms of alcohol-related aggression. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:400–413.

- Michelson D, Amsterdam J, Apter J, et al. Hormonal markers of stress response following interruption of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25:169–177.

- Allgulander C, Florea I, Huusom AK. Prevention of relapse in generalized anxiety disorder by escitalopram treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9:495–505.

- Montgomery SA, Huusom AK, Bothmer J. A randomised study comparing escitalopram with venlafaxine XR in primary care patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychobiology. 2004;50:57–64.

- GlaxoSmithKline. A double-blind comparative study of withdrawal effects following abrupt discontinuation of treatment with paroxetine in low or high dose or imipramine. GSK – Clinical Study Register 1992

- Ninan PT, Musgnung J, Messig M, Buckley G, Guico-Pabia CJ, Ramey TS. Incidence and timing of taper/posttherapy-emergent adverse events following discontinuation of desvenlafaxine 50 mg/d in patients with major depressive disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17

- Hartford J, Kornstein S, Liebowitz M, et al. Duloxetine as an SNRI treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: results from a placebo and active-controlled trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;22:167–174.

- Montgomery SA, Andersen HF. Escitalopram versus venlafaxine XR in the treatment of depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21:297–309.

- Sir A, D‘Souza RF, Uguz S, et al. Randomized trial of sertraline versus venlafaxine XR in major depression: efficacy and discontinuation symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1312–1320.

- Perahia DG, Kajdasz DK, Desaiah D, Haddad PM. Symptoms following abrupt discontinuation of duloxetine treatment in patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2005;89:207–212.

- Saxe PA, Arnold LM, Palmer RH, Gendreau RM, Chen W. Short-term (2-week) effects of discontinuing milnacipran in patients with fibromyalgia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:815–821.

- Vandel P, Sechter D, Weiller E, et al. Post-treatment emergent adverse events in depressed patients following treatment with milnacipran and paroxetine. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004;19:585–586.

- Giller E, Bialos D, Harkness L, Jatlow P, Waldo M. Long-term amitriptyline in chronic depression. Hillside J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;7:16–33.

- Charney DS, Heninger GR, Sternberg DE, Landis H. Abrupt discontinuation of tricyclic antidepressant drugs: evidence for noradrenergic hyperactivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;141:377–386.

- Dilsaver SC, Greden JF. Antidepressant withdrawal phenomena. Biol Psychiatry. 1984;19:237–256.

- Gahr M, Schonfeldt-Lecuona C, Kolle MA, Freudenmann RW. Withdrawal and discontinuation phenomena associated with tranylcypromine: a systematic review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2013;46:123–129.

- Stein DJ, Ahokas A, Albarran C, Olivier V, Allgulander C. Agomelatine prevents relapse in generalized anxiety disorder: a 6-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled discontinuation study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1002–1008.

- Fauchere PA. Recurrent, persisting panic attacks after sudden discontinuation of mirtazapine treatment: a case report. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2004;8:127–129.

- Davies J., Read J. A systematic review into the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal effects: Are guidelines evidence-based? Addictive Behaviors. 2019;97:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.027

- Renoir T. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant treatment discontinuation syndrome: a review of the clinical evidence and the possible mechanisms involved. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2013;4(45) doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00045

- Narayan V., Haddad P. M. Antidepressant discontinuation manic states: a critical review of the literature and suggested diagnostic criteria. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2010;25(3):306–313. doi: 10.1177/0269881109359094

- White P, Faingold CL. Emergent Antidepressant Discontinuation Syndrome Misdiagnosed as Delirium in the ICU. Case Rep Crit Care. 2019;2019:3925438. Published 2019 Aug 4. doi:10.1155/2019/3925438 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6699335

- Berber MJ. FINISH: remembering the discontinuation syndrome Flu-like symptoms, Insomnia, Nausea, Imbalance, Sensory disturbances, and Hyperarousal (anxiety/agitation) J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59

- Fava GA, Gatti A, Belaise C, Guidi J, Offidani E. Withdrawal symptoms after selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84:72–81.

- Chouinard G, Chouinard VA. New classification of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor withdrawal. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84:63–71.

- Warner C. H., Bobo W., Warner C., Reid S., Rachal J. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. American Family Physician. 2006;74(3):449–456.

- Davies J, Read J. A systematic review into the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal effects: Are guidelines evidence-based? Addict Behav. 2018 pii: S0306-4603(18)30834-7

- Khan A, Musgnung J, Ramey T, Messig M, Buckley G, Ninan PT. Abrupt discontinuation compared with a 1-week taper regimen in depressed outpatients treated for 24 weeks with desvenlafaxine 50 mg/d. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34:365–368.

- McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Tricamo E, Nunes EN, Quitkin FM. Paradoxical mood shifts to euthymia or hypomania upon withdrawal of antidepressant agents. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1993;13:224–225.

- Bloch M, Stager SV, Braun AR, Rubinow DR. Severe psychiatric symptoms associated with paroxetine withdrawal. Lancet. 1995;346

- Goldstein TR, Frye MA, Denicoff KD, et al. Antidepressant discontinuation-related mania: critical prospective observation and theoretical implications in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:563–567.

- MacCall C, Callender J. Mirtazapine withdrawal causing hypomania. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175

- Tint A, Haddad PM, Anderson IM. The effect of rate of antidepressant tapering on the incidence of discontinuation symptoms: a randomised study. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:330–332.

- Reeves RR, Mack JE, Beddingfield JJ. Shock-like sensations during venlafaxine withdrawal. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:678–681.

- Cosci F, Chouinard G, Chouinard V-A, Fava GA. The diagnostic clinical interview for drug withdrawal 1 (DID-W1)-new symptoms of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) or serotonin Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI): inter-rater reliability. Riv Psichiatr. 2018;53:95–99.

- Fava GA, Bernardi M, Tomba E, Rafanelli C. Effects of gradual discontinuation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in panic disorder with agoraphobia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;10:835–838.

- Andrews PW, Kornstein SG, Halberstadt LJ, Gardner CO, Neale MC. Blue again: perturbational effects of antidepressants suggest monoaminergic homeostasis in major depression. Front Psychol. 2011;2

- El-Mallakh RS, Briscoe B. Studies of long-term use of antidepressants. CNS Drugs. 2012;26:97–109.

- Viguera AC, Baldessarini RJ, Friedberg J. Discontinuing antidepressant treatment in major depression. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1998;5:293–306.

- Tapering of SSRI treatment to mitigate withdrawal symptoms. Lancet Psychiatry March 05, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30032-X

- Horowitz MA, Taylor D. Tapering of SSRI treatment to mitigate withdrawal symptoms. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(6):538–546.

- Groot PC Consensusgroep Tapering. Taperingstrips voor paroxetine en venlafaxine. Tijdschr Psychiatr. 2013; 55: 789-794

- Horowitz MA, Taylor D. Tapering of SSRI treatment to mitigate withdrawal symptoms. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019; 6: 538-546

- Tapering of SSRI treatment to mitigate withdrawal symptoms. Lancet Psychiatry Correspondence Volume 6, ISSUE 7, P561-562, July 01, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30182-8

- Fava GA, Gatti A, Belaise C, et al. Withdrawal symptoms after selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(2):72–81.

- Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Ghiani C, et al. Illness risk following rapid versus gradual discontinuation of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(8):934–941.

- Jha MK, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH. When discontinuing SSRI antidepressants is a challenge: management tips. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1176–1184.

- Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–781.

- Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–1367.

- LeBlanc A, Herrin J, Williams MD, et al. Shared decision making for antidepressants in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1761–1770.

- Dilsaver SC, Feinberg M, Greden JF. Antidepressant withdrawal symptoms treated with anticholinergic agents. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:249–251.

- Coupland NJ, Bell CJ, Potokar JP. Serotonin reuptake inhibitor withdrawal. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;16:356–362.

- DGPPN, BÄK, KBV, AWMF für die Leitliniengruppe Unipolare Depression. S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression-Langfassung. AWMF-Register Nr nvl-005.

- Phelps J. Tapering antidepressants: is 3 months slow enough? Med Hypotheses. 2011;77:1006–1008.

- Benazzi F. Fluoxetine for clomipramine withdrawal symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:661–662.

- Giakas WJ, Davis JM. Intractable withdrawal from venlafaxine treated with fluoxetine. Psychiatr Ann. 1997;27:85–92.

- Boschloo L, Spijker AT, Hoencamp E, et al. Predictors of the onset of manic symptoms and a (hypo) manic episode in patients with major depressive disorder. PLoS One. 2014;9 e106871

- Fava M, Detke MJ, Balestrieri M, Wang F, Raskin J, Perahia D. Management of depression relapse: re-initiation of duloxetine treatment or dose increase. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:328–336.

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391:1357–1366.