What is distichiasis

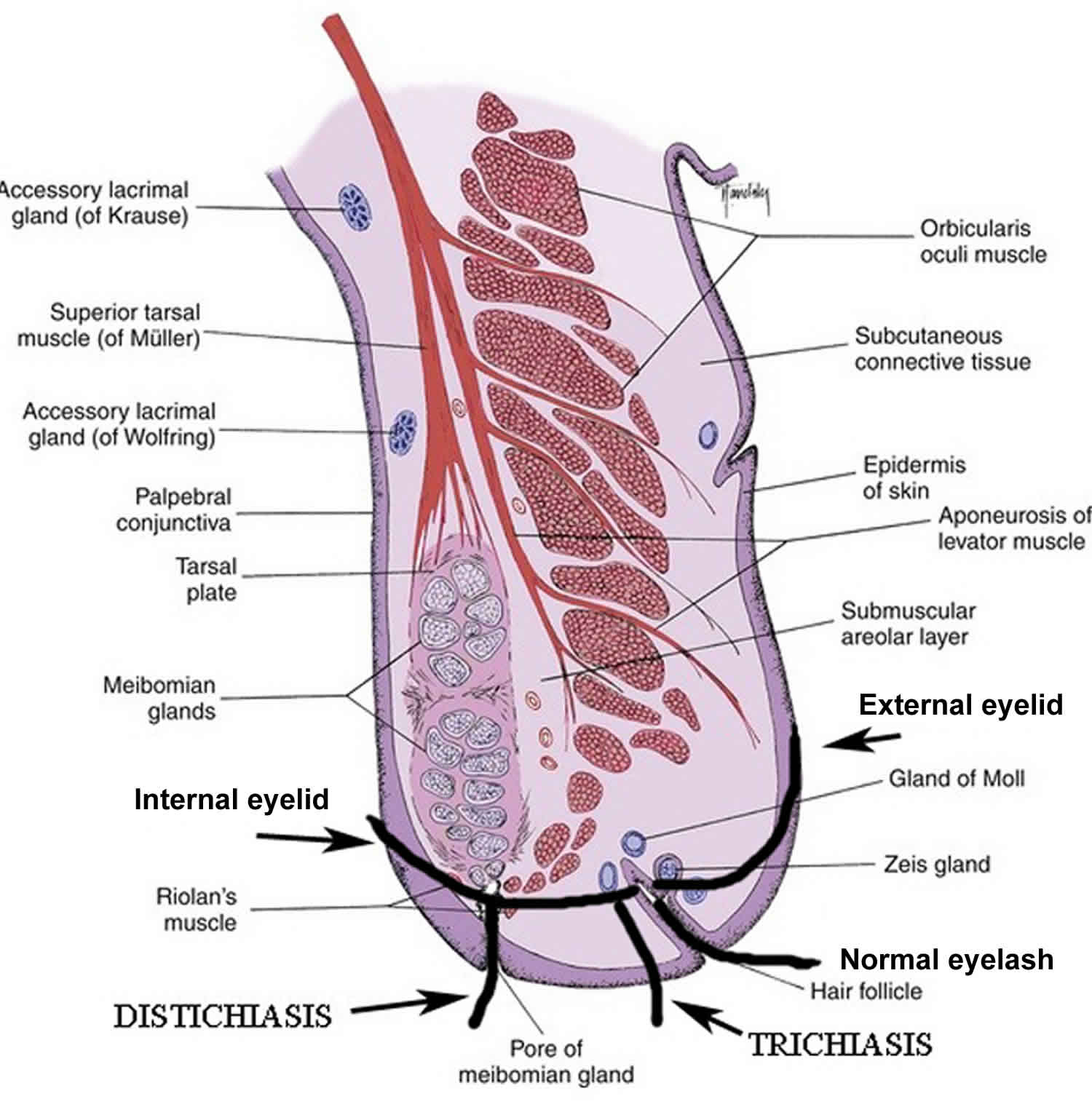

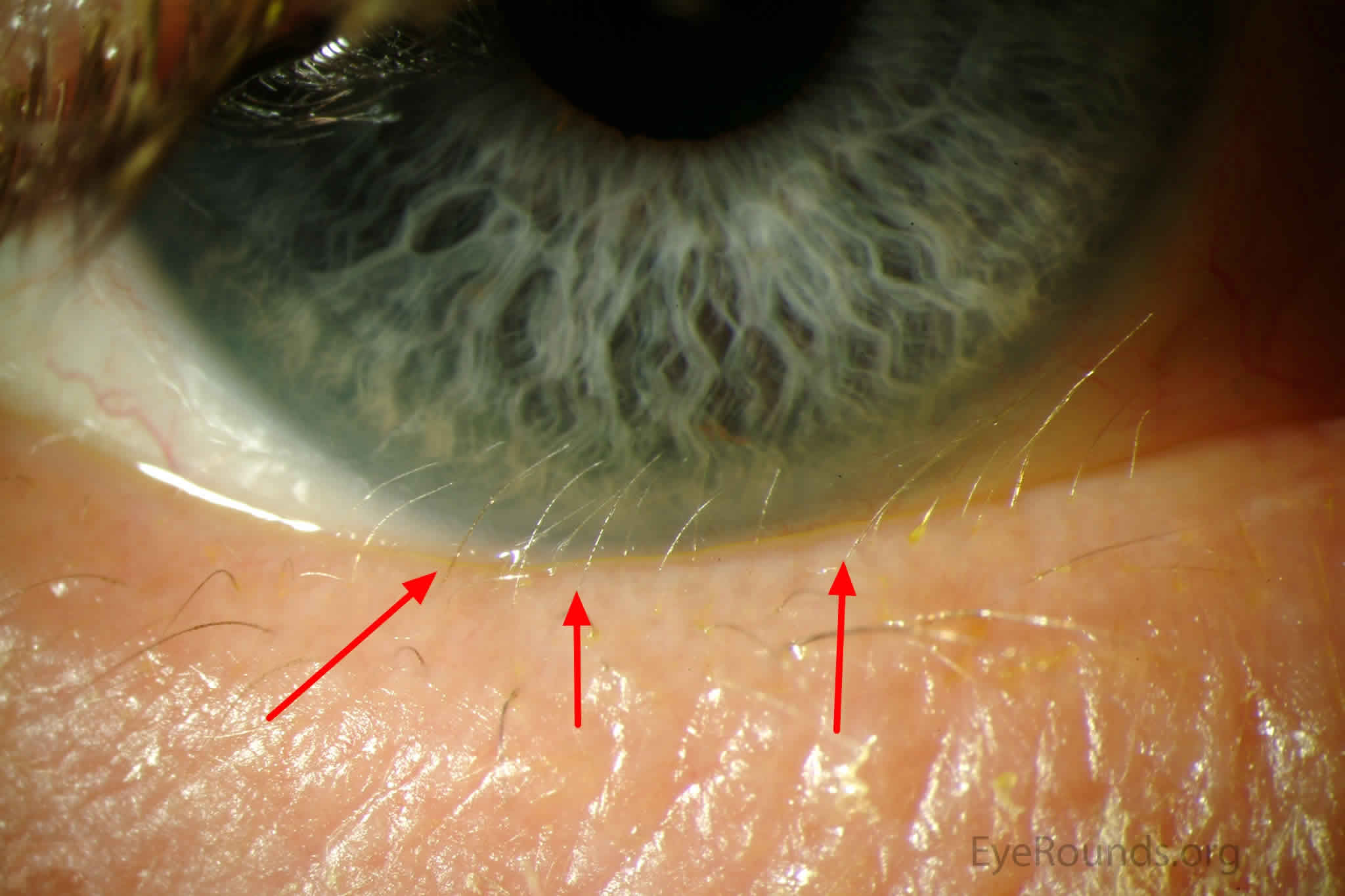

Distichiasis is a rare congenital or acquired presence of a partial or complete second row of eyelashes arising from the meibomian gland orifices, which can irritate and damage the cornea 1. These lashes are fine with little pigmentation but will cause corneal irritation. Distichiasis can affect the lower and upper lids. Various forms of distichiasis are seen, from a complete row of lashes to an irregular row. When these abnormal lashes come in contact with the cornea, they may cause severe irritation, epiphora, corneal abrasion, or even corneal ulcers.

Distichiasis may be congenital, in which case the pilosebaceous units differentiate into lashes instead of meibomian glands. The congenital form is dominantly inherited with complete penetrance. It can be isolated or associated with ptosis, strabismus, congenital heart defect, or mandibulofacial dysostosis. This defect may be related to the epithelial germ cells failure to differentiate completely to meibomian glands, instead they become pilosebaceous units. In the autosomal lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome 2, distichiasis is associated with limb lymphedema, and there may be cleft palate and cardiac abnormalities. Other congenital causes of distichiasis include mandibulofacial dystonia and Setleis syndrome (focal facial dermal dysplasia with upper eyelid lashes present in multiple rows or eyelashes may be completely absent).

Acquired or secondary distichiasis occurs after trauma or chronic irritation to the eyelid margin. In the acquired form, most cases involve the lower lids. Lashes can be fully formed or very fine, pigmented or nonpigmented, properly oriented or misdirected. Secondary distichiasis is seen in conditions that cause inflammation which in turn leads to metaplasia of the Meibomian glands forming lashes within the Meibomian glands. These conditions are similar to those causing trichiasis, including blepharitis, caustic injuries, meibomian gland dysfunction, meibomitis, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome,

Figure 1. Normal eyelashes vs distichiasis

Figure 2. Distichiasis

[Source 3 ]Distichiasis treatment

Distichiasis treatment includes epilation, use of cryotherapy, trephination, folliculectomy, lid split and treatment of the abnormal follicles and radiofrequency treatment of the follicles 4. In acquired distichiasis, there is eyelid inflammation (Meibomian gland dysfunction, cicatricial pemphigoid, Stevens-Johnson syndrome). Inflammation induces metaplasia of the Meibomian glands forming lashes within the Meibomian glands. There may be a need for application of a mucous membrane graft, particularly if there is mucocutaneous keratinization.

Lymphedema distichiasis syndrome

Lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome is a condition that affects the normal function of the lymphatic system, which is a part of the circulatory and immune systems. The lymphatic system produces and transports fluids and immune cells throughout the body. People with lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome develop puffiness or swelling (lymphedema) of the limbs, typically the legs and feet. Another characteristic of this syndrome is the growth of extra eyelashes (distichiasis), ranging from a few extra eyelashes to a full extra set on both the upper and lower lids. Distichiasis, which may be present at birth, is observed in 94% of affected individuals. These eyelashes do not grow along the edge of the eyelid, but out of its inner lining. When the abnormal eyelashes touch the eyeball, they can cause damage to the clear covering of the eye (cornea). About 75% of affected individuals have ocular findings including corneal irritation, recurrent conjunctivitis, and photophobia; other common findings include swollen and knotted (varicose) veins and droopy eyelids (ptosis). Related eye problems can include an irregular curvature of the cornea causing blurred vision (astigmatism) or scarring of the cornea. Other health problems associated with lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome include heart abnormalities and an opening in the roof of the mouth (a cleft palate).

All people with lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome have extra eyelashes present at birth. The age of onset of lymphedema varies, but it most often begins during puberty. Males usually develop lymphedema earlier than females and have more problems with cellulitis than females, but all affected individuals will develop lymphedema by the time they are in their forties.

The prevalence of lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome is unknown. Because the distichiasis can be overlooked during a medical examination, researchers believe that some people with this condition may be misdiagnosed as having lymphedema only.

Lymphedema distichiasis syndrome causes

Lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome is caused by mutations in the FOXC2 gene. The FOXC2 gene provides instructions for making a protein that plays a critical role in the formation of many organs and tissues before birth. The FOXC2 protein is a transcription factor, which means that it attaches (binds) to specific regions of DNA and helps control the activity of many other genes. Researchers believe that the FOXC2 protein has a role in a variety of developmental processes, such as the formation of veins and the development of the lungs, eyes, kidneys and urinary tract, cardiovascular system, and the transport system for immune cells (lymphatic vessels).

Lymphedema distichiasis syndrome inheritance pattern

This condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder.

In cases where the autosomal dominant condition does run in the family, the chance for an affected person to have a child with the same condition is 50% regardless of whether it is a boy or a girl. These possible outcomes occur randomly. The chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys and girls.

- When one parent has the abnormal gene, they will pass on either their normal gene or their abnormal gene to their child. Each of their children therefore has a 50% (1 in 2) chance of inheriting the changed gene and being affected by the condition.

- There is also a 50% (1 in 2) chance that a child will inherit the normal copy of the gene. If this happens the child will not be affected by the disorder and cannot pass it on to any of his or her children.

Figure 3. Lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

Lymphedema distichiasis syndrome diagnosis

Lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome should be suspected in individuals with the following clinical findings 5:

- Primary lymphedema (chronic swelling of the extremities caused by an intrinsic dysfunction of the lymphatic vessels) typically affecting the lower limbs ± genitalia with onset in late childhood or puberty

- Distichiasis (aberrant, extra eyelashes arising from the meibomian glands on the inner aspects of the inferior and/or superior eyelids, ranging from a full set of extra eyelashes to a single hair

- Varicose veins in the lower limbs presenting at puberty or early adulthood

- Ptosis (drooping upper eyelid) of one or both eyes

- Other less frequent findings:

- Congenital heart disease including bicuspid aortic valves

- Cleft palate ± Pierre Robin sequence

- Renal anomalies

- Spinal extradural arachnoid cysts

- Nonimmune hydrops fetalis

- Antenatal hydrothoraces

- Neck webbing

Establishing the diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome is established in a proband with one of the following:

- Distichiasis and lymphedema (although a young child may have no evidence of lymphedema)

- Distichiasis and a family history of lower-limb lymphedema

- Lower-limb lymphedema and a family history of distichiasis

If clinical findings are not diagnostic, the identification of a heterozygous pathogenic variant in FOXC2 by molecular genetic testing can confirm the diagnosis.

Molecular genetic testing approaches can include a combination of gene-targeted testing (single-gene testing, multigene panel) and comprehensive genomic testing (exome sequencing, exome array, genome sequencing) depending on the phenotype.

Gene-targeted testing requires that the clinician determine which gene(s) are likely involved, whereas genomic testing does not. Because the phenotype of lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome can be specific to this condition, individuals with the distinctive findings described above are likely to be diagnosed using gene-targeted testing, whereas those in whom the diagnosis of lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome has not been considered are more likely to be diagnosed using genomic testing.

Lymphedema distichiasis syndrome treatment

To establish the extent of disease and needs of in an individual diagnosed with lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome, the evaluations following initial diagnosis is summarized in Table 1 (if not performed as part of the evaluation that led to the diagnosis) are recommended.

Table 1. Recommended evaluations following initial diagnosis in individuals with Lymphedema-Distichiasis Syndrome

| System/ Concern | Evaluation | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Eyes | Ophthalmologic evaluation | Slit lamp evaluation for distichiasis & related problems of corneal irritation, recurrent conjunctivitis, & photophobia Assess for ptosis. Assess for strabismus. |

| Lymphedema | Physical examination of lower legs to document presence of lymphedema & any evidence of cellulitis | Isotope lymphoscintigraphy to detect lymphatic weakness before onset of swelling |

| Vascular | Physical examination of varicose veins w/young onset (adolescence / early adulthood) | Venous duplex scans |

| Cleft palate | Assess for cleft palate or Pierre Robin sequence. | |

| Cardiovascular | Assess for congenital heart defects. | Echocardiogram Further evaluation if clinical evidence suggests arrhythmias |

| Spine | Assess for spinal extradural arachnoid cyst. | Cysts can result in fluctuating symptoms (e.g., when enlarged, they may compress the root or cord & result in pain or weakness) Spinal MRI if symptomatic |

| Assess for scoliosis. | ||

| Renal | Renal ultrasound evaluation | Assess for renal anomalies. |

| Miscellaneous/ Other | Consultation w/clinical geneticist &/or genetic counselor |

Eyes

- Conservative management of symptomatic distichiasis with lubrication or epilation (plucking), or more definitive management with cryotherapy, electrolysis, or lid splitting 6. Recurrence is possible even with more definitive treatment.

- Surgery for ptosis if clinically indicated (e.g., obscured vision, cosmetic appearance)

Lymphedema

Refer to a lymphedema therapist for management of edema (fitting hosiery, massage). Although the edema cannot be cured, some improvement may be possible with the use of carefully fitted hosiery and/or bandaging, which may reduce the size of the swelling as well as the associated discomfort. The implementation of hosiery prior to the development of lymphedema may be beneficial in reducing the extent of edema.

The following are appropriate:

- Prevention of secondary cellulitis in areas with lymphedema, particularly as cellulitis may aggravate the degree of edema. Prophylactic antibiotics (e.g., penicillin V 500 mg/day) are recommended for recurrent cellulitis.

- Prompt treatment of early cellulitis with appropriate antibiotics. It may be necessary to give the first few doses intravenously if there is severe systemic upset.

- Prevention of foot infections (particularly athlete’s foot / infected eczema) by treatment with appropriate creams/ointments

Note: (1) Diuretics are not effective in the treatment of lymphedema. (2) Cosmetic surgery is often associated with disappointing results.

Pregnancy Management

Edema may be exacerbated during pregnancy, but often improves after delivery. The patient should continue compression and bandage treatment as long as possible but this should be adapted to the patient’s needs (e.g., thigh-length compression garments instead of tights).

Varicose veins

- Manage varicose veins conservatively with compression garments if possible, as surgery could aggravate the edema and increase the risk of infection or cellulitis.

Cardiac anomalies/arrhythmia

- Manage as per standard practice.

Spine

- Spinal extradural arachnoid cyst. Refer individuals with symptomatic spinal cysts (i.e., any neurologic signs or symptoms, especially in the lower limbs) to a neurosurgeon.

- Scoliosis. Standard treatment

Renal malformations

- Standard treatment

Surveillance

Table 2. Recommended surveillance for individuals with Lymphedema-Distichiasis Syndrome

| System/Concern | Evaluation | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Eyes | Slit light examination of eyes | As required for control of symptoms from distichiasis |

| Lymphedema | Lymphoscintigraphy at diagnosis, then clinical assessment | 1-2x/yr, but regular lymphedema therapy (every 6 mos) 1 |

| Varicose veins | Clinical assessment | 1-2x/yr |

| Cleft palate | As per craniofacial team | |

| Cardiovascular | As per cardiologist | |

| Spine | Investigate w/spine MRI if symptomatic only | |

| Renal | As per treating nephrologist/urologist |

Footnote: 1) See fact sheet for more information (https://vascern.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Fiches_Pediatric_and_Primary_Lymphedema_FINAL-web.pdf).

[Source 5 ] References- Nowinski TS. 2011. Entropion. In: Tse DT, editor. Color Atlas of Oculoplastic Surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p 44-53.

- Mansour S, Brice GW, Jeffery S, Mortimer P. Lymphedema-Distichiasis Syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle; Seattle (WA): Mar 29, 2005.

- Distichiasis. https://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/atlas/pages/distichiasis/index.htm

- Patel BC, Joos ZP. Diseases of the Eyelashes. [Updated 2019 Apr 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537100

- Mansour S, Brice GW, Jeffery S, et al. Lymphedema-Distichiasis Syndrome. 2005 Mar 29 [Updated 2019 Apr 4]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2019. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1457

- O’Donnell BA, Collin JR. Distichiasis: management with cryotherapy to the posterior lamella. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:289–92.