Erythema migrans

Erythema migrans is the most typical sign of Lyme disease (present in 70–80% of cases) and often appears at the site of the bites from several species of Ixodes ticks (Ixodes scapularis, Ixodes pacificus, Ixodes Ricinus) 1. Erythema migrans is a red, enlarging rash, flat or slightly raised, and may reach from 4 to 20 inches (12 to 35 cm) across (the average rash is 6 inches, or 17 cm). Erythema migrans usually appears 7–14 days (range 3–33 days) after the infected tick bite. It starts at the site of the tick bite as a red papule or macule that gradually expands. The size of the rash can reach several dozens of centimetres in diameter. A central spot surrounded by clear skin that is in turn ringed by an expanding red rash (like a bull’s-eye) is the most typical appearance. Erythema migrans may also present as a uniform erythematous patch or red patch with central hardening and blistering. The redness can vary from pink to very intensive purple.

Erythema migrans is mostly asymptomatic, but can be itchy, sensitive or warm if touched. It is rarely painful. Fatigue, chills, headache, low-grade fever, muscle and joint pain, may occur briefly and then recur if the disease progresses. Lymph glands near the tick bite may be swollen.

Erythema migrans disappears spontaneouslly within 3–4 weeks. If left untreated the disease may disseminate, affect other organs, and progress to the next stage. Untreated Lyme disease can cause monoarticular or oligoarticular arthritis, neurologic complications (most commonly facial nerve palsy) and cardiac complications (varying degrees of atrioventricular block) may occur 2. Early recognition of the cutaneous manifestation of Lyme disease and prompt treatment is of utmost importance to halt progression of the disease and limit further complications. When erythema migrans is promptly treated with appropriate antimicrobial agents, the prognosis is excellent. Persons in endemic areas should take measures to prevent tick bites.

Lyme disease is caused by the tick-borne spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, is an important cause of infection in endemic regions of North America and Eurasia and has a strong seasonality with the majority of the cases occurring during the months of May through August 3. In North America, over 90% of Lyme disease cases are reported from the East Coast of the United States, although significant numbers of cases are also reported from the upper Midwest of the United States and certain areas of Canada and the West Coast.

Erythema migrans rash:

- Occurs in approximately 70 to 80 percent of Lyme disease infected persons

- Begins at the site of a tick bite after a delay of 3 to 30 days (average is about 7 days)

- Expands gradually over several days reaching up to 12 inches or more (30 cm) across

- May feel warm to the touch but is rarely itchy or painful

- Sometimes clears as it enlarges, resulting in a target or “bull’s-eye” appearance

- May appear on any area of the body.

Erythema migrans is the most common manifestation of Lyme disease, with at least 80% of infected persons developing a variation of this skin lesion in the first weeks of infection 4. Erythema migrans is characterized by a round red patch gradually expanding over time, typically reaching at least 5 cm or greater in size 5. The localized rash appears three to thirty days after an infected tick bite and disappears naturally if left untreated over days to weeks 3. Though it has been documented that erythema migrans can have various manifestations 6, the classic “target” shaped erythema migrans is best known in the literature and most common on public health information and handouts 7. In reality, a classic target erythema migrans manifests in only approximately 20% of patients with erythema migrans, with the majority of erythema migrans lacking the central clearing or ring-within-a-ring pattern 5.

Figure 1. Erythema migrans (“classic” Lyme disease rash)

Erythema migrans causes

Erythema migrans is the most common objective manifestation of Lyme disease caused by the tick-borne spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne disease in the United States. Lyme disease is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi and rarely, Borrelia mayonii 8. Lyme disease is transmitted to humans through the bite of infected blacklegged ticks. Typical symptoms include fever, headache, fatigue, and a characteristic skin rash called erythema migrans. If left untreated, infection can spread to joints, the heart, and the nervous system. Lyme disease is diagnosed based on symptoms, physical findings (e.g., rash), and the possibility of exposure to infected ticks. Laboratory testing is helpful if used correctly and performed with validated methods. Most cases of Lyme disease can be treated successfully with a few weeks of antibiotics. Steps to prevent Lyme disease include using insect repellent, removing ticks promptly, applying pesticides, and reducing tick habitat. The ticks that transmit Lyme disease can occasionally transmit other tickborne diseases as well.

Lyme disease can affect children and adults. Infection most often occurs in forestry workers and in those who have been enjoying recreational activities in areas where ticks reside.

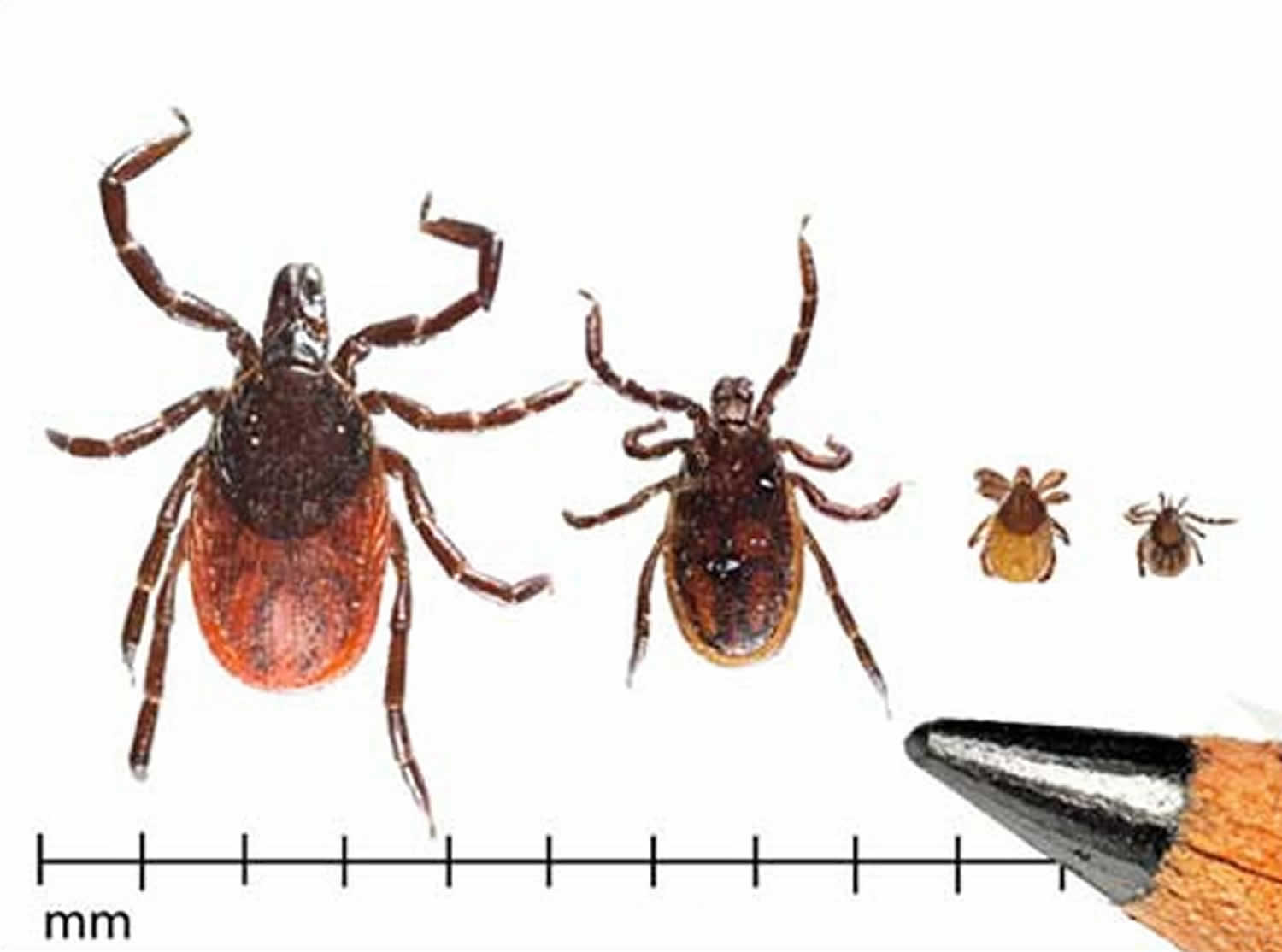

Ticks can attach and feed in any part of the human body. The bite is painless. Because they are very tiny (just 2 mm in size) nymph bites are often overlooked. Borrelia are transmitted from the midgut of the infected tick to the attached skin when attachment lasts for 36–48 hours.

Several things can happen after being bitten by an infected tick.

- The body’s defence mechanisms can overwhelm and eliminate the infecting bacteria.

- The bacteria can remain localized at the site of the bite and cause a localized skin infection.

- The bacteria may disseminate via the blood and lymphatic system to other organs and cause a multi-system inflammatory disease.

Figure 2. Western-Blacklegged ticks (Ixodes pacificus)

Erythema migrans prevention

Prevention is the best way to avoid tick-borne illness. Reducing exposure to ticks is the best defense against Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and other tickborne infections. You and your family can take several steps to prevent and control Lyme disease. Except for tick-borne encephalitis, there is no vaccine available to prevent tick-borne disease. Protective clothing, such as long pants, long sleeves, and closed shoes should be worn in tick-infested areas, particularly in the late spring in summer when most cases occur. Pant legs should be tucked into socks when walking through high grass and brush. Permethrin, which is an insecticide, may be applied to clothing and is quite effective in repelling ticks. Other tick repellents such as diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) may be applied to skin or clothing, with variable effectiveness. DEET can be quite toxic, with effects ranging from local skin irritation to seizures. DEET should be avoided in infants.

Use insect repellents and protective clothing when in tick-infested areas. Tuck pant legs into socks. Carefully check the skin and hair after being outside and remove any ticks you find.

If you find a tick on your child, write the information down and keep it for several months. Many tick-borne diseases do not show symptoms right away, and you may forget the incident by the time your child becomes sick with a tick-borne disease.

Before you go outdoors

- Know where to expect ticks. Ticks live in grassy, brushy, or wooded areas, or even on animals. Spending time outside walking your dog, camping, gardening, or hunting could bring you in close contact with ticks. Many people get ticks in their own yard or neighborhood.

- Treat clothing and gear with products containing 0.5% permethrin. Permethrin can be used to treat boots, clothing and camping gear and remain protective through several washings. Alternatively, you can buy permethrin-treated clothing and gear.

- Use Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, IR3535, Oil of Lemon Eucalyptus (OLE), para-menthane-diol (PMD), or 2-undecanone (https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents). EPA’s helpful search tool (https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents/find-repellent-right-you) can help you find the product that best suits your needs. Always follow product instructions.

- DO NOT use insect repellent on babies younger than 2 months old.

- DO NOT use products containing OLE or PMD on children under 3 years old.

Avoid contact with ticks

- Avoid wooded and brushy areas with high grass and leaf litter.

- Walk in the center of trails.

After you come indoors

Check your clothing for ticks. Ticks may be carried into the house on clothing. Any ticks that are found should be removed. Tumble dry clothes in a dryer on high heat for 10 minutes to kill ticks on dry clothing after you come indoors. If the clothes are damp, additional time may be needed. If the clothes require washing first, hot water is recommended. Cold and medium temperature water will not kill ticks.

Examine gear and pets. Ticks can ride into the home on clothing and pets, then attach to a person later, so carefully examine pets, coats, and daypacks.

Shower soon after being outdoors. Showering within two hours of coming indoors has been shown to reduce your risk of getting Lyme disease and may be effective in reducing the risk of other tickborne diseases. Showering may help wash off unattached ticks and it is a good opportunity to do a tick check.

Check your body for ticks after being outdoors. Conduct a full body check upon return from potentially tick-infested areas, including your own backyard. Use a hand-held or full-length mirror to view all parts of your body. Check these parts of your body and your child’s body for ticks:

- Under the arms

- In and around the ears

- Inside belly button

- Back of the knees

- In and around the hair

- Between the legs

- Around the waist

Figure 3. Check your body for ticks

Preventing tick bites

Tick exposure can occur year-round, but ticks are most active during warmer months (April-September). Know which ticks are most common in your area (see geographic distribution of ticks that bite humans below).

When spending time outdoors, make these easy precautions part of your routine:

- Wear enclosed shoes and light-colored clothing with a tight weave to spot ticks easily

- Scan clothes and any exposed skin frequently for ticks while outdoors

- Stay on cleared, well-traveled trails

- Use insect repellant containing DEET (Diethyl-meta-toluamide) on skin or clothes if you intend to go off-trail or into overgrown areas

- Avoid sitting directly on the ground or on stone walls (havens for ticks and their hosts)

- Keep long hair tied back, especially when gardening

- Do a final, full-body tick-check at the end of the day (also check children and pets)

When taking the above precautions, consider these important facts:

- If you tuck long pants into socks and shirts into pants, be aware that ticks that contact your clothes will climb upward in search of exposed skin. This means they may climb to hidden areas of the head and neck if not intercepted first; spot-check clothes frequently.

- Clothes can be sprayed with either DEET or Permethrin. Only DEET can be used on exposed skin, but never in high concentrations; follow the manufacturer’s directions.

- Upon returning home, clothes can be spun in the dryer for 20 minutes to kill any unseen ticks

- A shower and shampoo may help to remove crawling ticks, but will not remove attached ticks. Inspect yourself and your children carefully after a shower. Keep in mind that nymphal deer ticks are the size of poppy seeds; adult deer ticks are the size of apple seeds.

Any contact with vegetation, even playing in the yard, can result in exposure to ticks, so careful daily self-inspection is necessary whenever you engage in outdoor activities and the temperature exceeds 45° F (the temperature above which deer ticks are active). Frequent tick checks should be followed by a systematic, whole-body examination each night before going to bed. Performed consistently, this ritual is perhaps the single most effective current method for prevention of Lyme disease.

Finally, prevention is not limited to personal precautions. Those who enjoy spending time in their yards can reduce the tick population around the home by:

- keeping lawns mowed and edges trimmed

- clearing brush, leaf litter and tall grass around houses and at the edges of gardens and open stone walls

- stacking woodpiles neatly in a dry location and preferably off the ground

- clearing all leaf litter (including the remains of perennials) out of the garden in the fall

- having a licensed professional spray the residential environment (only the areas frequented by humans) with an insecticide in late May (to control nymphs) and optionally in September (to control adults).

Erythema migrans symptoms

Erythema migrans is the most common skin manifestation of Lyme disease caused by the tick-borne spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Lyme disease can affect any part of the body, most commonly the skin, central nervous system, joints, heart, and rarely the eyes and liver. A small bump or redness at the site of a tick bite that occurs immediately and resembles a mosquito bite, is common. This irritation generally goes away in 1-2 days and is not a sign of Lyme disease.

Erythema migrans is characterized by flat to slightly raised, erythematous skin lesion on the thigh, back, shoulder, and calf. Erythema migrans can be asymptomatic, but can be painful or itchy, and sometimes tender. A punctum, the bite mark from the preceding tick bite, can be found around the center of the lesion 9. Most patients do not recall a preceding tick bite. Despite a characteristic appearance, erythema migrans is not pathognomonic for Lyme disease and must be distinguished from other similar appearing skin lesions.

Signs and symptoms of untreated Lyme disease

Untreated Lyme disease can produce a wide range of symptoms, depending on the stage of infection. These include fever, rash, facial paralysis, and arthritis.

Early signs and symptoms (3 to 30 days after tick bite)

- Fever, chills, headache, fatigue, muscle and joint aches, and swollen lymph nodes may occur in the absence of rash

- Erythema migrans rash:

- Occurs in approximately 70 to 80 percent of infected persons

- Begins at the site of a tick bite after a delay of 3 to 30 days (average is about 7 days)

- Expands gradually over several days reaching up to 12 inches or more (30 cm) across

- May feel warm to the touch but is rarely itchy or painful

- Sometimes clears as it enlarges, resulting in a target or “bull’s-eye” appearance

- May appear on any area of the body

Later signs and symptoms (days to months after tick bite)

- Severe headaches and neck stiffness

- Additional erythema migrans rashes on other areas of the body

- Facial palsy (loss of muscle tone or droop on one or both sides of the face)

- Arthritis with severe joint pain and swelling, particularly the knees and other large joints.

- Intermittent pain in tendons, muscles, joints, and bones

- Heart palpitations or an irregular heart beat (Lyme carditis)

- Episodes of dizziness or shortness of breath

- Inflammation of the brain and spinal cord

- Nerve pain

- Shooting pains, numbness, or tingling in the hands or feet

Erythema migrans diagnosis

Erythema migrans is a clinical diagnosis; serologic and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays are unnecessary. Leukopenia and thrombocytopenia are indicative of either an alternative diagnosis, or coinfection with another tick-borne pathogen.

Early diagnosis of Lyme disease is essential. Diagnosis can be made on the presence of erythema migrans and other symptoms, plus a history of or evidence of a tick bite. Laboratory tests are usually not necessary in the early stage of erythema migrans,

Undetected or ignored early symptoms may be followed by more severe symptoms weeks, months or even years after the initial infection. Certain laboratory tests are then recommended to confirm the diagnosis and should be interpreted by an expert.

- Antibody titres to B burgdorferi using enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) or immunofluorescent assay.

- Positive results should be confirmed by Western immunoblot.

- Skin biopsy: histopathology

- Erythema migrans is often non-specific

- Borrelial lymphocytoma

- Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans

- The organism can be cultured or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for the organism can be done on the skin specimen.

Positive antibodies to B. burgdorferi can be in many cases detected for many years after the successful treatment.

Tick bites may transmit other infections like tick-born encephalitis, anaplasmosis and babesiosis. Co-infections should be considered if symptoms of Lyme disease are severe or prolonged, in case of high fever, and abnormal blood tests results (leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, or elevation of liver transaminases).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) currently recommends a two-step testing process for Lyme disease 10. Both steps are required and can be done using the same blood sample. If this first step is negative, no further testing is recommended. If the first step is positive or indeterminate (sometimes called “equivocal”), the second step should be performed. The overall result is positive only when the first test is positive (or equivocal) and the second test is positive (or for some tests equivocal).

Key points to remember

- Most Lyme disease tests are designed to detect antibodies made by the body in response to infection.

- Antibodies can take several weeks to develop, so patients may test negative if infected only recently.

- Antibodies normally persist in the blood for months or even years after the infection is gone; therefore, the test cannot be used to determine cure.

- Infection with other diseases, including some tickborne diseases, or some viral, bacterial, or autoimmune diseases, can result in false positive test results.

- Some tests give results for two types of antibody, IgM and IgG. Positive IgM results should be disregarded if the patient has been ill for more than 30 days.

Erythema migrans treatment

People treated with appropriate antibiotics in the early stages of Lyme disease usually recover rapidly and completely. Antibiotics commonly used for oral treatment include doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime axetil. People with certain neurological or cardiac forms of illness may require intravenous treatment with antibiotics such as ceftriaxone or penicillin.

Treatment regimens listed in the following table are for localized (early) Lyme disease 11. These regimens are guidelines only and may need to be adjusted depending on a person’s age, medical history, underlying health conditions, pregnancy status, or allergies.

Several studies on the treatment of Lyme disease showed most people recover when treated within a few weeks of antibiotics taken by mouth. In a small percentage of cases, symptoms such as fatigue (being tired) and muscle aches can last for more than 6 months. This condition is known as “Post-treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome”, although it is often called “chronic Lyme disease.” Why some patients experience Post-treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome is not known. Some experts believe that Borrelia burgdorferi can trigger an “auto-immune” response causing symptoms that last well after the infection itself is gone. Auto–immune responses are known to occur following other infections, including campylobacter (Guillain-Barré syndrome), chlamydia (Reiter’s syndrome), and strep throat (rheumatic heart disease). Other experts hypothesize that Post-treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome results from a persistent but difficult to detect infection. Finally, some believe that the symptoms of Post-treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome are due to other causes unrelated to the patient’s Borrelia burgdorferi infection.

Unfortunately, there is no proven treatment for Post-treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome. Although short-term antibiotic treatment is a proven treatment for early Lyme disease, the National Institutes of Health have found that long-term outcomes are no better for patients who received additional prolonged antibiotic treatment than for patients who received placebo. Long-term antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease has been associated with serious, sometimes deadly complications.

Patients with Post-treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome usually get better over time, but it can take many months to feel completely well. If you have been treated for Lyme disease and still feel unwell, see your healthcare provider to discuss additional options for managing your symptoms. If you are considering long-term antibiotic treatment for ongoing symptoms associated with a Lyme disease infection, please talk to your healthcare provider about the possible risks of such treatment.

| Age Category | Drug | Dosage | Maximum | Duration, Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | Doxycycline | 100 mg, twice per day orally | N/A | 10-21* |

| Cefuroxime axetil | 500 mg, twice per day orally | N/A | 14-21 | |

| Amoxicillin | 500 mg, three times per day orally | N/A | 14-21 | |

| Children | Amoxicillin | 50 mg/kg per day orally, divided into 3 doses | 500 mg per dose | 14-21 |

| Doxycycline | 4.4 mg/kg per day orally, divided into 2 doses | 100 mg per dose | 10-21* | |

| Cefuroxime axetil | 30 mg/kg per day orally, divided into 2 doses | 500 mg per dose | 14-21 |

Footnotes: *Recent publications suggest the efficacy of shorter courses of treatment for early Lyme disease.

For people intolerant of amoxicillin, doxycycline, and cefuroxime axetil, the macrolides azithromycin, clarithromycin, or erythromycin may be used, although they have a lower efficacy. People treated with macrolides should be closely monitored to ensure that symptoms resolve.

References- Grubhoffer L, Golovchenko M, Vancová M, Zacharovová-Slavícková K, Rudenko N, Oliver JH. Lyme borreliosis: insights into tick-/host-borrelia relations. Folia Parasitol 2005; 52:279–94.

- Wormser GP. Early Lyme disease. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:2794–801.

- Aucott JN, Crowder LA, Yedlin V, Kortte KB. Bull’s-Eye and Nontarget Skin Lesions of Lyme Disease: An Internet Survey of Identification of Erythema Migrans. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:451727. doi:10.1155/2012/451727 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3485866

- Steere AC. Lyme disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(2):115–125.

- Tibbles CD, Edlow JA. Does this patient have erythema migrans? Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297(23):2617–2627.

- Smith RP, Schoen RT, Rahn DW, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcome of early lyme disease in patients with microbiologically confirmed erythema migrans. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2002;136(6):421–428.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Lyme Disease: Signs and Symptoms of Lyme Disease, 2012.

- Lyme Disease. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/index.html

- Dumpis U, Crook K, Oksi J. Tick‐borne encephalitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:882–90.

- Lyme Disease Diagnosis and Testing. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/diagnosistesting/index.html

- Hu LT. Lyme Disease. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Nov 1;165(9):677.