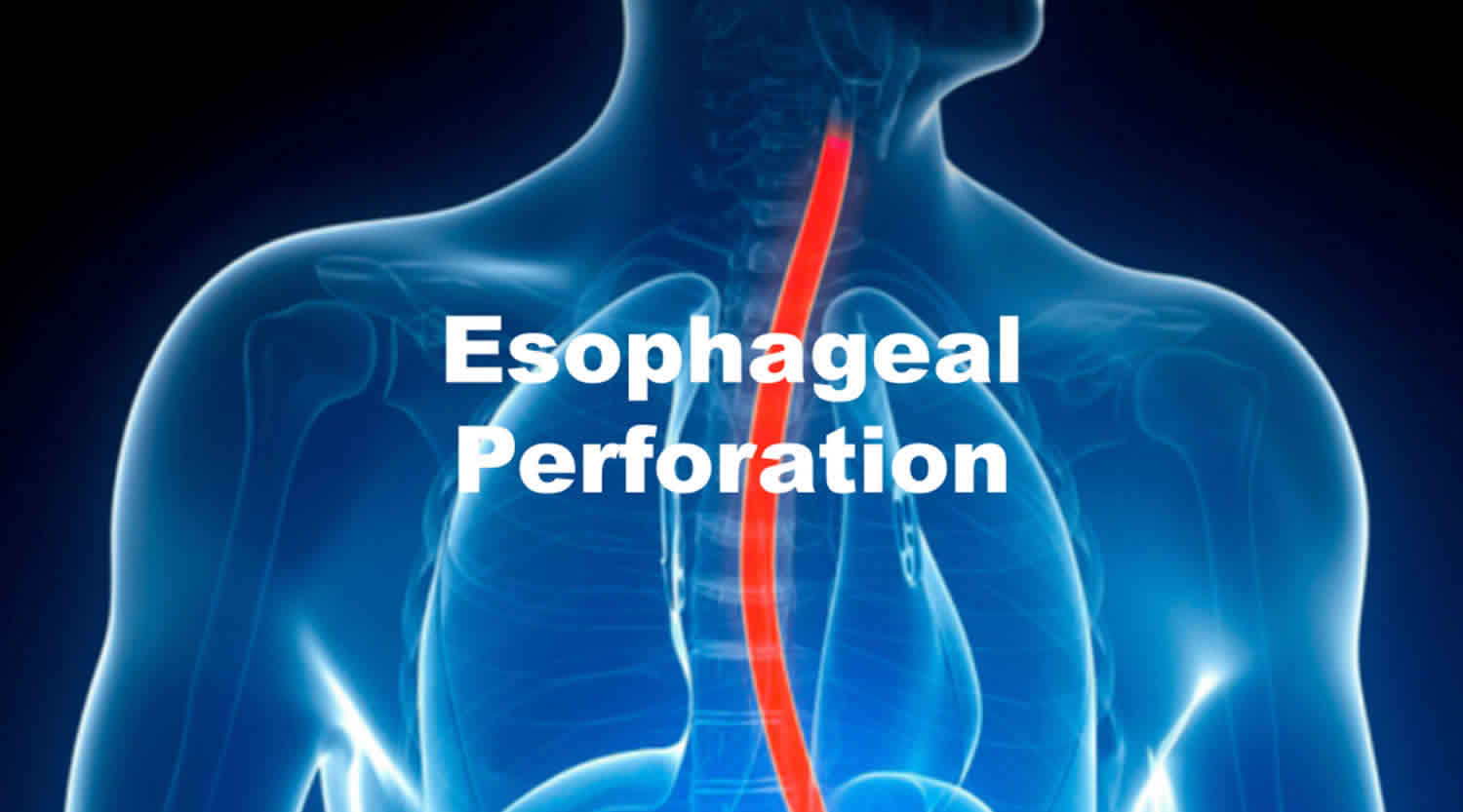

Esophageal tear

Esophageal tear also known as esophageal rupture, is a rare but serious medical emergency with a very high mortality rate over 40%, especially if the diagnosis is delayed in septic patients 1. While the true incidence of esophageal tear is unclear 2, the majority of esophageal tear cases (up to 59%) are iatrogenic 3 resulting from esophagoscopy 4 despite the actual risk of esophageal perforation during endoscopy being low 5. Boerhaave syndrome, a spontaneous esophageal rupture secondary to forceful vomiting and retching, accounts for about 15% of the cases 6. Foreign-body ingestion accounts for 12% of the cases, trauma 9%, operative injury 2%, tumors 1%, and other causes 2% 6.

Esophageal perforation occurs in 3 in 100,000 people in the United States. Of those cases, 25% are cervical; 55%, intrathoracic; and 20%, abdominal 7.

Thoracic esophageal perforations occur frequently 6 and can lead to serious complications and death without alarm 8, owing to the mediastinal contamination that ensues soon after the perforation 5. This contamination, which is exacerbated by the negative intrathoracic pressure that draws esophageal contents into the mediastinum 9, evokes an overwhelming inflammatory response 10 leading to mediastinitis, initially chemical mediastinitis, followed by bacterial invasion and severe mediastinal necrosis 5. Eventually, sepsis ensues leading to multiple-organ failure and death 11. The extent of this inflammation (mediastinitis), and thus the morbidity and mortality of esophageal perforation, depends not only on the cause and location of the perforation but also on the time interval between onset and access to appropriate treatment 12. It has been shown that early detection reduces mortality by over 50% 10 and treatment delays over 24 hours increase mortality significantly 13.

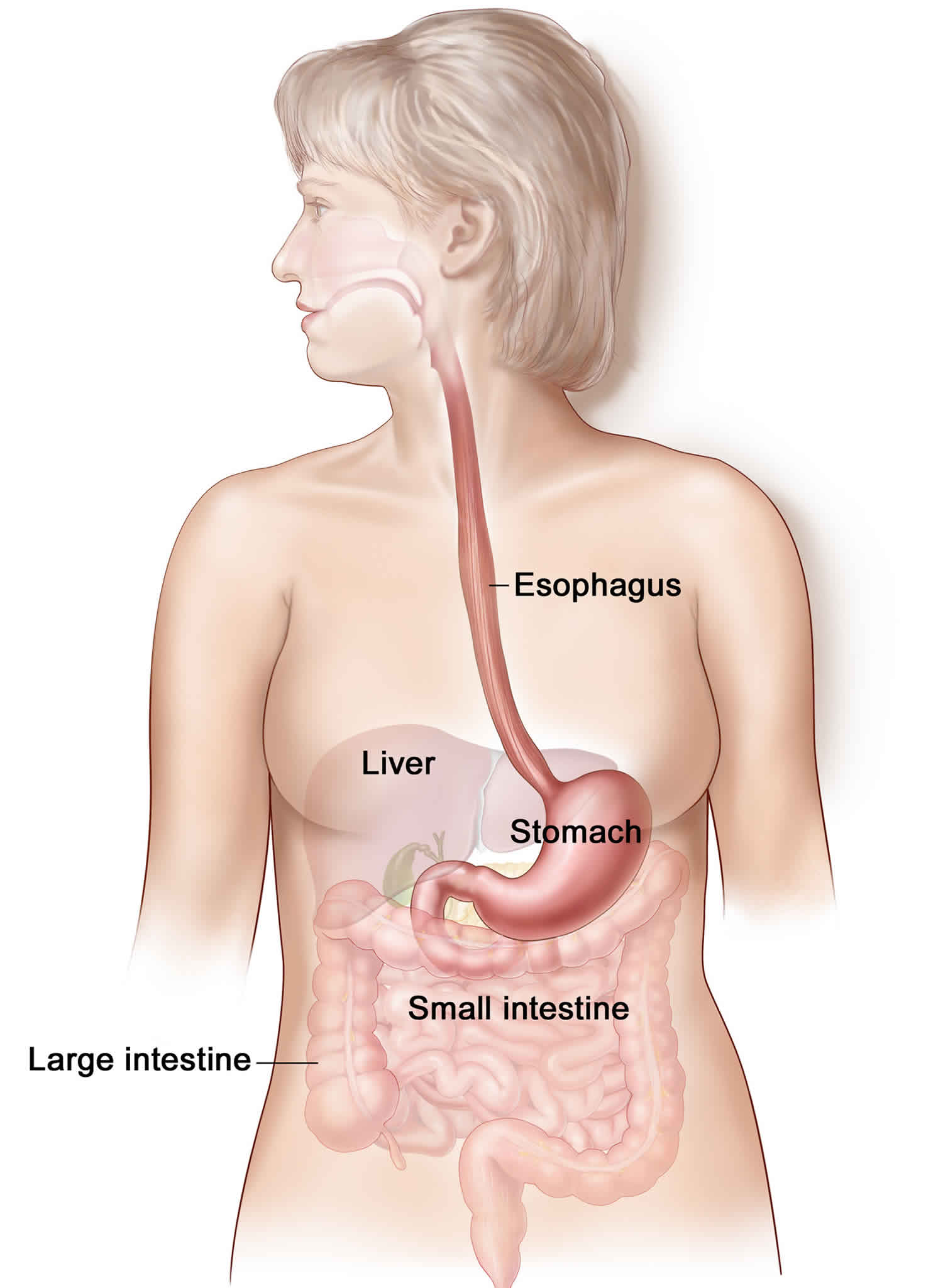

Esophagus anatomy

The esophagus is a 25-cm long fibromuscular tube that connects the pharynx to the stomach. It starts in the neck at the level of C6 vertebra, extending through the mediastinum until its insertion in the diaphragm at the level T10 vertebra via a separate opening in the right crus of the diaphragm. Along its vertical course, the esophagus has three constrictions:

- The first constriction is approximately 15 cm from the upper incisor teeth, where the esophagus begins at the cricopharyngeal sphincter at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra.

- The second constriction is approximately 23 cm from the upper incisor, which is the landmark of the crossing of the aortic arch and the left main bronchus.

- The third constriction is approximately 40 cm from the upper incisor, where it pierces the diaphragm and forms the physiologic lower esophageal sphincter at the tenth thoracic vertebra.

The esophagus is divided into three portions:

- The cervical esophagus extends from the cricopharyngeus muscle to the suprasternal notch and is supplied by the inferior thyroid artery.

- The thoracic esophagus, considered the longest segment, extends from suprasternal notch to the diaphragm and is supplied by bronchial and esophageal branches of the descending thoracic aorta.

- The abdominal esophagus, the shortest division, extends from the diaphragm to the cardia of the stomach and is supplied by branches of the left phrenic and left gastric arteries.

Figure 1. Esophagus

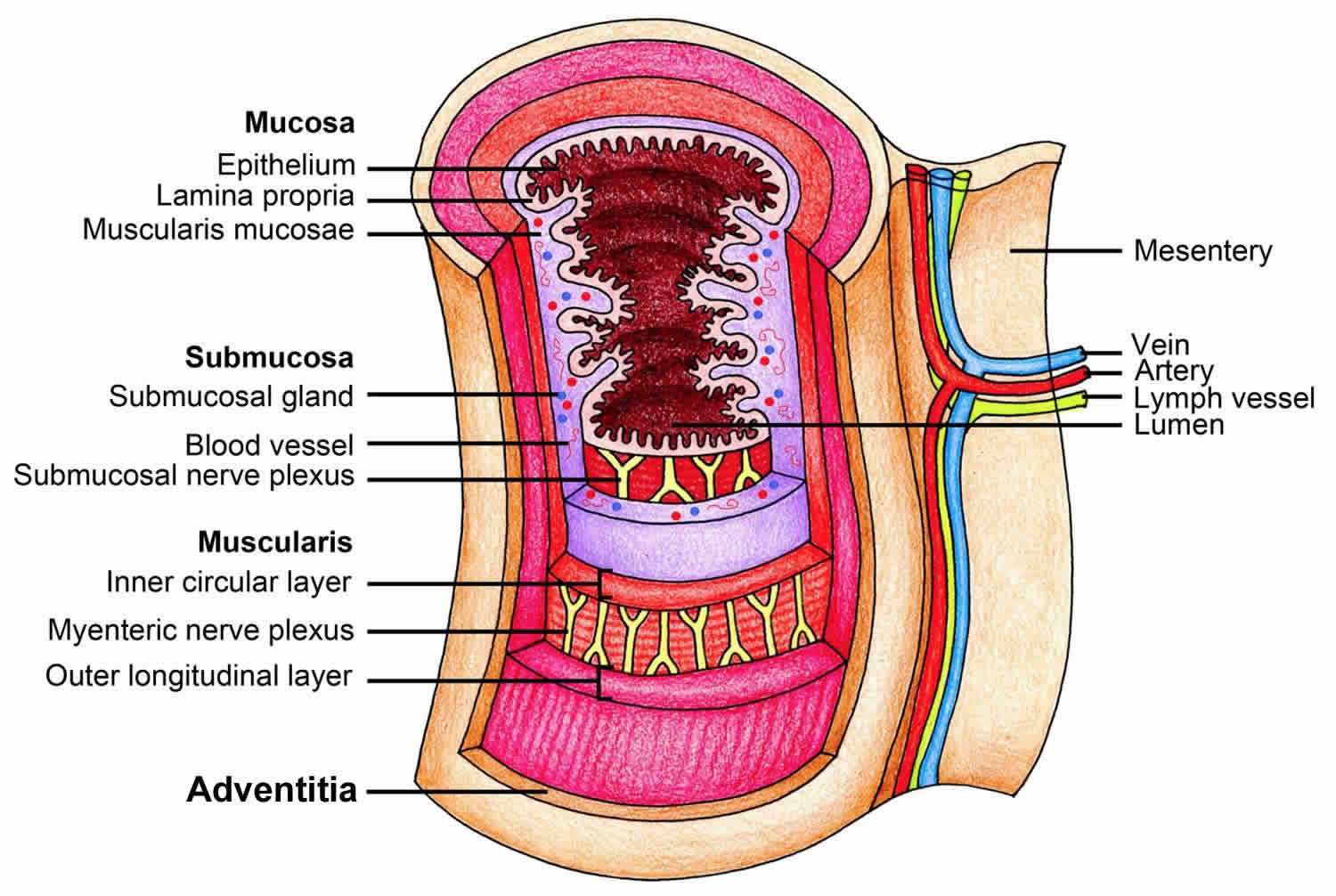

Figure 2. Esophagus anatomy

Esophageal tear causes

Esophageal perforation may be due to several mechanisms, including direct piercing, shearing along the longitudinal axis, bursting from radial forces, and thinning from necrosis of the esophageal wall.

Iatrogenic injury through esophageal instrumentation is the leading cause of perforation by either piercing or shearing and may be due to any number of procedures, especially endoscopy and dilatation of strictures 14. Such esophageal tears often occur near the pharyngoesophageal junction where the wall is weakest. Because the esophagus is surrounded by loose stromal connective tissue, the infectious and inflammatory response can disseminate easily to nearby vital organs, thereby making the esophageal perforation a medical emergency and increasing the likelihood of serious complications. Older age (>65 years) and underlying esophageal disease (tumor, stricture) predisposes toward esophageal perforation with instrumentation, which often occurs distal to the affected area. Esophageal perforation during surgery most often occurs in the abdominal esophagus.

Spontaneous esophageal rupture (Boerhaave syndrome) occurs secondary to a sudden increase in intraluminal pressures, usually due to violent vomiting or retching, and often follows heavy food and alcohol intake. In more than 90% of cases, perforation occurs in the lower third of the esophagus; most frequently, the tear is in the left posterolateral region (90%) and may extend superiorly. The predilection for left-side esophageal perforation is due to the lack of adjacent supporting structures, thinning of the musculature in the lower esophagus, and anterior angulation of the esophagus at the left diaphragmatic crus. Fifty percent of esophageal ruptures occur in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), suggesting that ease of pressure transfer from the abdominal to thoracic esophagus may facilitate esophageal rupture.

Shearing forces due to rapid increases in intragastric pressure against a closed pylorus result in a Mallory-Weiss tear. These longitudinal mucosal lacerations occur most commonly at the gastroesophageal junction or gastric cardia, especially if a hiatal hernia is present, and often present with hematemesis. Ultimately, these esophageal tears can perforate if the pressure increases are unrelieved.

The cervical esophagus is the most common site of esophageal perforation by several other mechanisms as well, particularly in the region of the pyriform sinus. Trauma, almost uniformly penetrating, shows an affinity for the upper esophagus, while toxic ingestions and foreign bodies can directly damage the cervical esophagus or become lodged and cause insidious erosion of the muscle wall.

Iatrogenic causes

Iatrogenic esophageal perforations predominate the causes of esophageal perforation, accounting for up to 85% of cases. Iatrogenic esophageal perforations are a group of perforations caused by instrumentation for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes commonly include endoscopy, sclerotherapy, variceal ligation, pneumatic dilation, bougienage, and laser treatment. Placement of endotracheal, nasogastric, and Blakemore tubes represent less common iatrogenic causes. Diagnostic endoscopy, performed almost exclusively with flexible endoscopes, carries a low risk of perforation; however, therapeutic interventions such as pneumatic dilation, hemostasis, stent placement, foreign body extraction, cancer palliation, and endoscopic ablation techniques can dramatically increase the risk of perforation. Iatrogenic perforation is common in the hypopharynx or the distal esophagus while spontaneous rupture may occur in the posterolateral wall of the esophagus just above its diaphragmatic hiatus. Despite being rare overall, iatrogenic esophageal perforations can also be the result of invasive surgical maneuvers, with fundoplication and esophageal myotomy being the most common operations associated with the complication 15.

Boerhaave syndrome

Boerhaave syndrome consistently accounts for about 15% of all perforations, normally secondary to vomiting after heavy food and alcohol intake, but possible by any action that abruptly increases intra-abdominal pressure against a closed superior esophageal sphincter. Spontaneous esophageal rupture usually occurs in a longitudinal fashion and varies in size from 0.6 cm to 8.9 cm long, with the left side more commonly affected than the right (90%).

Foreign bodies

Swallowed foreign bodies may directly injure the esophagus by penetrating the tissue or becoming lodged at a point of esophageal narrowing, leading to pressure necrosis and wall weakness; pills and coins are common culprits. Ingestion of caustic chemicals may lead to direct wall inflammation and damage. Esophageal ruptures secondary to a foreign body impaction are rare. Esophageal distal third impactions are the most common site for impaction predisposed by peptic stricture, achalasia or esophagitis. Middle third impactions are frequently reported to be facilitated by strictures or obstructive neoplasms.

Trauma

Trauma represents an important cause of perforation, estimated at up to 10% of cases. Traumatic injuries of the esophagus that are secondary to penetrating or blunt forces are rare but life-threatening causes of esophageal perforations. Penetrating trauma is much far more prevalent than blunt, often in the form of knife or gun wounds, and is associated with significant injury to important adjacent cervical structures. Blunt trauma may affect any portion of the esophagus 16 and the diagnosis is often delayed secondary to other injuries.

Intraoperative esophageal perforation

Intraoperative esophageal perforation is a recognized complication of surgery, especially cardiothoracic or fundoplication, accounting for around 2% of all perforations.

Esophageal tear symptoms

The clinical manifestations of esophageal perforations depend on several factors including the etiology of the perforation, the location of the perforation (cervical, intrathoracic or intra-abdominal), the severity of contamination, injury of nearby mediastinal structures (trachea in a case of penetrating trauma in cervical esophageal perforations or the pericardium in case of spontaneous thoracic perforations), and the time elapsed from the perforation until treatment 17.

- Cervical esophageal perforations can be presented with neck pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, or dysphonia. Crepitus or tenderness can be elicited on neck palpation.

- Thoracic esophageal perforations are presented with retrosternal chest pain, often preceded by retching and vomiting in patients diagnosed with Boerhaave syndrome. Patients may have crepitus on chest wall palpation caused by subcutaneous emphysema. Mediastinal crackling can be heard on auscultation in patients with mediastinal emphysema. Symptoms and signs of pleural effusion such as dyspnea, tachypnea, dullness on chest percussion, and decreased fremitus may be detected.

- Abdominal esophageal perforations are presented with epigastric pain radiating to the shoulder which might be associated with nausea or vomiting. Transmural tears, extending through the serosa is frequently complicated by peritoneal contamination and patients present with acute peritonitis.

- Fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, and cyanosis are signs of late mediastinitis and shock and considered a poor prognostic indicator.

The classic presentation of spontaneous esophageal rupture is severe vomiting or retching followed by acute, severe chest or epigastric pain. Other symptoms may include the following 18:

- Boerhaave syndrome has also been reported with abdominal or chest pain following straining, childbirth, weight lifting, fits of coughing or laughing, hiccuping, blunt trauma, seizures, and forceful swallowing.

- The presence of fever; pain in the neck, upper back, chest, or abdomen; dysphagia; odynophagia; dysphonia; or dyspnea following esophageal instrumentation should raise suspicion for perforation.

- Patients with thoracic or abdominal perforations may present with any of the above symptoms, as well as low back pain, shoulder pain referred from diaphragmatic irritation, increased discomfort lying flat, or true acute abdomen.

- The ingestion of a caustic toxin or foreign body preceding any of the above symptoms may indicate perforation.

- A history of preexisting upper gastrointestinal pathology (gastroesophageal reflux disease, hiatal hernia, carcinoma, strictures, radiation therapy, Barrett esophagus, varices, achalasia, infection) raises a patient’s risk of perforation.

- Older age (>65 years) is a significant risk factor for perforation during instrumentation.

- Vomiting blood (hematemesis), while occasionally present, is normally not a predominant symptom.

Although the physical examination is often nonspecific, certain findings can be helpful, including the following:

- Subcutaneous emphysema is palpable in the neck or chest in up to 60% of perforations but requires at least an hour to develop after the initial injury.

- Tachycardia and tachypnea are common initial physical examination findings, but fever may not be present for hours to days.

- The Mackler triad, consisting of vomiting, chest pain, and subcutaneous emphysema, is classically associated with spontaneous esophageal rupture, though it is only fully present in about 50% of cases.

- Auscultation of the chest can be of particular value. The Hamman sign is a raspy, crunching sound heard over the precordium with each heartbeat caused by mediastinal emphysema, often present with thoracic or abdominal perforations. Breath sounds may be reduced on the side of the perforation due to a contamination of the pleural space, often on the left.

- In cases of delayed presentation, patients may be critically ill and present with significant hypotension.

Esophageal tear complications

Esophageal tear complications include pneumonia, mediastinitis, sepsis, empyema, and adult respiratory distress syndrome.

Because of improved management, a significant number of patients now survive; recurrent spontaneous ruptures of the esophagus have been described.

Esophageal injuries secondary to penetrating trauma often involve adjacent structures such as the spinal cord and trachea.

Esophageal tear diagnosis

Diagnosis of esophageal perforation is challenging owing to a nonspecific and varied clinical presentation 3 that mimics a myriad of other disorders such as myocardial infarction and peptic ulcer perforation 19. Patients may present with any combination of nonspecific signs and symptoms including fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, acute onset chest pain, dysphagia, vomiting, and shortness of breath 20. A high index of suspicion is therefore needed for recognition of esophageal perforation 21. Once suspected, patients should be evaluated quickly with a combination of radiographs and esophagograms 6. Accurate diagnosis may however require added investigations including computed tomography and flexible esophagoscopy 12.

- Plain radiography is used to detect air that has escaped from the perforated esophagus. Subcutaneous emphysema in the case of cervical esophageal rupture, mediastinal air (pneumomediastinum), and widening is indicative of thoracic perforation while free air under the diaphragm is clear evidence of abdominal esophageal perforation. Other findings that may show on plain X-rays include pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, hydrothorax, hydropneumothorax, and air in soft tissues of the prevertebral space.

- Contrast esophagography is used to establish and to confirm the diagnosis of esophageal perforation. Leakage of contrast material is a sure sign to establish the diagnosis of perforation. Dye extravasation can also help determine the location and extent of the rupture. Barium contrast studies are superior to water contrast materials in terms of accuracy and specificity; however, due to the higher risk of barium-induced chemical mediastinitis, water contrast studies are preferred.

- Computed tomography (CT scan) of the chest and abdomen should be performed when esophageal perforation is suspected. It has the advantage of showing intrathoracic or intra-abdominal collections that require percutaneous or surgical drainage. CT findings may include periesophageal fluid collections (pleural effusion, ascites), esophageal thickening, and pneumomediastinum.

Esophageal tear treatment

Patients with esophageal perforations are of high mortality risk; even with prompt medical care, mortality can reach as high as 36% to 50% 7. Any patient with an esophageal tear should be expeditiously transported to the emergency department with intravenous access, supplemental oxygen with a secure airway, and pain medication as necessary.

Treatment of esophageal perforations remains a challenge 13 and the appropriate management is controversial 8. Traditionally, surgery has been the mainstay of treatment 19, but recent reports emphasize a shift in treatment strategies with nonoperative approaches becoming more common 11. It has been shown that, with careful patient selection, nonoperative management can be the treatment of choice for esophageal perforations 1 with good outcomes 12. Altorjay et al. 22 and others have suggested criteria for selection of nonoperative treatment including early perforations (or contained leak if diagnosis delayed); leak draining back to the esophagus; nonseptic patients; perforation not involving a neoplasm, abdominal esophagus, or distal obstruction; and availability of an experienced thoracic surgeon and contrast. When these established guidelines are followed, survival rates of up to 100% have been reported 20.

Patients selected for nonoperative treatment are started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, intravenous fluids, oxygen therapy, adequate analgesia, and gastric acid suppression and kept nil by mouth in an intensive care unit 23. A nasogastric tube is placed to clear gastric contents and limit further contamination 8 and mediastinal contamination drained percutaneously/radiologically 23 via the chest tubes, thereby converting the esophageal perforations to esophagocutaneous fistulae that heal similar to gastrointestinal fistulae 1. Apart from observation, the range of conservative management is growing, with the increasing use of endoscopic stents, clips, vacuum sponge therapy, and fibrin glue application 12 for the selected patients. Notably though, even with meticulous patient selection, up to 20% develop multiple complications within 24 hours and require surgical intervention 4.

Initial management

- ICU admission for all unstable patients or high-risk patients with multiple comorbidities

- Hemodynamic monitoring, volume resuscitation, and stabilization.

- Nil by mouth (Nil Per Os)

- TPN (Total Parenteral Nutrition)

- Intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics and antifungals

- Intravenous proton pump inhibitors

- Percutaneous drainage of any fluid collection

- Assessment for operative versus nonoperative management

- Feeding J-tube

Standard care

- Endoscopic stent placement: Performed in selected stable patients; esophageal perforations can be covered with synthetic stents delivered via esophageal endoscopy. Failure of this intervention is mostly attributed to either stent migration, malpositioning, or inability to create an air/fluid tight seal between the stent and the margins of the esophageal defect.

- Drainage with/out debridement: Surgical drainage is performed without further operation as most of the esophageal perforations will heal if drained adequately.

Surgical Management

Operative management is required for most patients to minimize morbidity and mortality.

- Patients diagnosed early (less than 24 hours after the perforation) can be treated with debridement of all devitalized contaminated tissue followed by primary repair. In addition, the primary repair should be enhanced with the use of a vascularized pedicle flap using serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, or the diaphragm.

- Patients who present by extensive leakage of fluid, substantial tissue necrosis, or devitalization or by major fluid collections should undergo emergent surgical stenting, debridement, or drainage to restore the integrity of the esophagus.

- In rare situations, diversion procedures or resection of the esophagus with proximal esophagostomy and feeding gastrostomy/jejunostomy can be a valid option in patients with extensive contamination who are not candidates for primary repair due to friability of the surrounding tissue or pre-existing esophageal disease (inoperable malignancy).

- Postoperative healing can be enhanced by placing a feeding jejunostomy or gastrostomy tube to abstain from oral feeding for more prolonged periods of time and ensure maximum healing conditions for the esophagus, especially when substantial extraluminal leakage exists. However, this operation is optional and relies on the surgeon’s preference.

- Oral feedings should be restored when the patient is stable, with a contrast esophagram study confirming the integrity of the esophagus and the absence of any leakage.

- Vogel S. B., Rout W. R., Martin T. D., et al. Esophageal perforation in adults: aggressive, conservative treatment lowers morbidity and mortality. Annals of Surgery. 2005;241(6):1016–1023. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000164183.91898.74

- Søreide J. A., Viste A. Esophageal perforation: diagnostic work-up and clinical decision-making in the first 24 hours. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. 2011;19, article 66 doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-19-66.

- Vidarsdottir H., Blondal S., Alfredsson H., Geirsson A., Gudbjartsson T. Oesophageal perforations in Iceland: a whole population study on incidence, aetiology and surgical outcome. Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgeon. 2010;58(8):476–480. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1250347

- Merchea A., Cullinane D. C., Sawyer M. D., et al. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy-associated gastrointestinal perforations: a single-center experience. Surgery. 2010;148(4):876–882. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.010

- Brinster C. J., Singhal S., Lee L., Marshall M. B., Kaiser L. R., Kucharczuk J. C. Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2004;77(4):1475–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.08.037

- Mantzoukis K., Kpadimitriou K., Kouvelis I., et al. Endoscopic closure of an iatrogenic rupture of upper esophagus (Lannier’s triangle) with the use of endoclips—case report and review of the literature. Annals of Gastroenterology. 2011;24(1):55–58.

- Kassem MM, Wallen JM. Esophageal Perforation, Rupture, And Tears. [Updated 2019 Jun 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532298

- Kaman L., Iqbal J., Kundil B., Kochhar R. Management of esophageal perforation in adults. Gastroenterology Research. 2010;3(6):235–244.

- Salo J. A., Isolauri J. O., Heikkila L. J., et al. Management of delayed esophageal perforation with mediastinal sepsis. Esophagectomy or primary repair? Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1993;106(6):1088–1091.

- Ko E., O-Yurvati A. H. Iatrogenic esophageal injuries: evidence-based management for diagnosis and timing of contrast studies after repair. International Surgery. 2012;97(1):1–5. doi: 10.9738/cc73.1

- Søreide J. A., Viste A. Esophageal perforation: diagnostic work-up and clinical decision-making in the first 24 hours. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. 2011;19, article 66 doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-19-66

- Troja A., Käse P., El-Sourani N., Miftode S., Raab H. R., Antolovic D. Treatment of esophageal perforation: a single-center expertise. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1457496914546435

- Persson S., Elbe P., Rouvelas I., et al. Predictors for failure of stent treatment for benign esophageal perforations—a single center 10-year experience. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(30):10613–10619. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10613

- Esophageal Rupture and Tears in Emergency Medicine. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/775165-overview

- Huu Vinh V, Viet Dang Quang N, Van Khoi N. Surgical management of esophageal perforation: role of primary closure. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2019 Mar;27(3):192-198.

- Bernard AW, Ben-David K, Pritts T. Delayed presentation of thoracic esophageal perforation after blunt trauma. J Emerg Med. 2008 Jan. 34(1):49-53.

- Milosavljevic T, Popovic D, Zec S, Krstic M, Mijac D. Accuracy and Pitfalls in the Assessment of Early Gastrointestinal Lesions. Dig Dis. 2019;37(5):364-373.

- Esophageal Rupture and Tears in Emergency Medicine Clinical Presentation. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/775165-clinical

- Razi E., Davoodabadi A., Razi A. Spontaneous esophageal perforation presenting as a right-sided pleural effusion: a case report. Tanaffos. 2013;12(4):53–57.

- Addas R., Berjaud J., Renaud C., Berthoumieu P., Dahan M., Brouchet L. Esophageal perforation management: a single-center experience. Open Journal of Thoracic Surgery. 2012;2(4):111–117. doi: 10.4236/ojts.2012.24023

- Hoover E. L. The diagnosis and management of esophageal perforations. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1991;83(3):246–248.

- Altorjay Á., Kiss J., Vörös A., Bohák Á. Nonoperative management of esophageal perforations. Is it justified? Annals of Surgery. 1997;225(4):415–421. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199704000-00011

- Petersen J. M. The use of a self-expandable plastic stent for an iatrogenic esophageal perforation. Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2010;6(6):389–391.